Abstract

Purpose

Infection-related outcomes associated with asplenia or impaired splenic function in survivors of childhood cancer remains understudied.

Methods

Late infection-related mortality was evaluated in 20,026 5-year survivors of childhood cancer (diagnosed < 21 years of age from 1970 to 1999; median age at diagnosis, 7.0 years [range, 0 to 20 years]; median follow-up, 26 years [range, 5 to 44 years]) using cumulative incidence and piecewise-exponential regression models to estimate adjusted relative rates (RRs). Splenic radiation was approximated using average dose (direct and/or indirect) to the left upper quadrant of the abdomen (hereafter, referred to as splenic radiation).

Results

Within 5 years of diagnosis, 1,354 survivors (6.8%) had a splenectomy and 9,442 (46%) had splenic radiation without splenectomy. With 62 deaths, the cumulative incidence of infection-related late mortality was 1.5% (95% CI, 0.7% to 2.2%) at 35 years after splenectomy and 0.6% (95% CI, 0.4% to 0.8%) after splenic radiation. Splenectomy (RR, 7.7; 95% CI, 3.1 to 19.1) was independently associated with late infection-related mortality. Splenic radiation was associated with increasing risk for late infection-related mortality in a dose-response relationship (0.1 to 9.9 Gy: RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 0.9 to 4.5; 10 to 19.9 Gy: RR, 5.5; 95% CI, 1.9 to 15.4; ≥ 20 Gy: RR, 6.0; 95% CI, 1.8 to 20.2). High-dose alkylator chemotherapy exposure was also independently associated with an increased risk of infection-related mortality (RR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1 to 3.4).

Conclusion

Splenectomy and splenic radiation significantly increase risk for late infection-related mortality. Even low- to intermediate-dose radiation exposure confers increased risk, suggesting that the spleen is highly radiosensitive. These findings should inform long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood cancer and should lead clinicians to avoid or reduce radiation exposure involving the spleen whenever possible.

INTRODUCTION

Many survivors of childhood cancer are asplenic, either as a result of primary surgical treatment of their disease or for historical staging of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). In addition, those who received splenic radiation are at risk for developing impaired splenic function.1-4 Although the asplenic state (anatomic or functional) is known to be associated with increased risk for severe infections, long-term implications for survivors of childhood cancer are poorly understood. In particular, it is not known if low doses of radiation to the spleen are associated with impaired function.

Since King and Shumacker5 published their report in 1952 describing infection and subsequent death in four young children after splenectomy, there has been great interest in understanding and mitigating the infectious risks associated with asplenia. For survivors of childhood cancer, existing literature examining risk for infection associated with splenectomy is limited almost exclusively to those who had staging laparotomy for HL reporting an elevated risk of both early and late risk for serious infection.6-11

With attempts to comprehensively investigate the effects of asplenia on survivors of childhood cancer, it is important to consider not only radiotherapy with treatment fields directly irradiating the spleen but also a broader spectrum of radiotherapy treatments where the spleen may have been in-field, partially in-field, near-field, or out-of-field, resulting in doses from as low as 0.1 Gy to > 40 Gy. Currently, patients treated with high-dose radiotherapy (≥ 40 Gy) to the spleen are considered to be at highest risk for development of impaired splenic function.2 There is assumed to be a reduced risk of developing splenic dysfunction after receiving lower splenic doses; however, a dose-response relationship between radiation dose and risk for impaired splenic function remains unknown.4

Our purpose was to characterize the risk of late infection-related mortality among survivors of childhood cancer who underwent splenectomy or who received splenic radiation. For those patients who received radiotherapy, we aimed to determine if a dose-response relationship exists and, if so, to characterize that response across a broad spectrum of splenic doses.

METHODS

Population

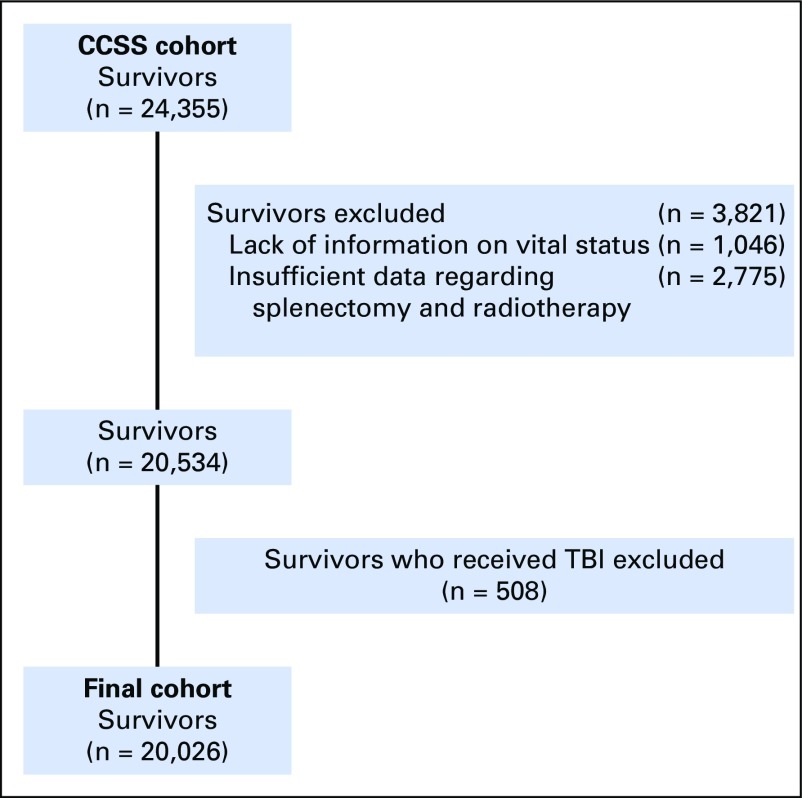

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) is a multi-institutional, retrospective cohort study with longitudinal follow-up of 5-year survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed between 1970 and 1999. Participants were younger than age 21 years at the time of diagnosis with leukemia, lymphoma, Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, bone tumors, or CNS tumors. The current analysis includes 26 participating institutions in the United States. Survivors without complete data regarding splenectomy status, radiotherapy received, and vital status were excluded (Fig 1). In addition, because of the established association between late infections and total body irradiation, these survivors were excluded. CCSS is estimated to have captured the data of 20% of 5-year survivors in the United States and has been shown to be representative of the larger population of long-term survivors of childhood cancer.12-14 Details of the CCSS methodology have been previously published.12,15,16

Fig 1.

Inclusion of survivors and derivation of final cohort. CCSS, Childhood Cancer Survivor Study; TBI, total body irradiation.

Outcomes and Covariates

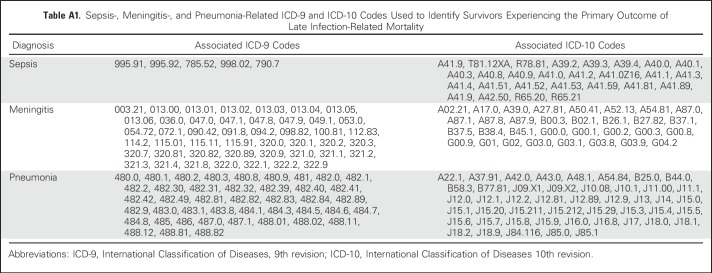

Patients eligible for participation were included in a search for matching death records using the National Death Index through 2013. Underlying and multiple causes of death for deceased patients using the International Classification of Diseases 9th and 10th revisions were provided by the National Death Index; the initiating cause of death was identified using standardized rules for classification of deaths. For deaths that predated the National Death Index (ie, those in 1975 to 1978; n = 139), death certificates from states where deaths occurred were requested.14,17 The primary outcome was late (> 5 years from diagnosis) infection-related mortality, defined as death attributable to sepsis, meningitis, or pneumonia on the basis of established associations with asplenia.18 Corresponding International Classification of Diseases 9th and 10th revision codes are listed in Appendix Table A1 (online only). The primary outcome was compared among survivors who underwent splenectomy, radiotherapy, or neither of these within 5 years of cancer diagnosis.

Dose of splenic radiation was determined as follows: for patients receiving radiotherapy within 5 years of diagnosis, the radiotherapy record was abstracted for treatment field parameters, including dose, orientation, energy, field size, weighting, blocking, and anatomic borders. Treatment was reconstructed on age-specific mathematical phantoms. For each reconstruction, the average dose to the left upper quadrant of the abdomen was computed and used as a surrogate for average spleen dose using the dose-reconstruction method described by Stovall et al.19 Splenectomy and chemotherapy exposure were abstracted from the medical record of all participants.

Covariates included demographic data (ie, age, sex, race), chronic health conditions (on the basis of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.03),20 occurrence of secondary malignant neoplasm (SMN) or late recurrence, and chemotherapy received within 5 years of diagnosis (anthracyclines, alkylating agents, methotrexate, cisplatin, and carboplatin). Cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED)21-23 and doxorubicin-equivalent doses24 were calculated for alkylators and anthracyclines, respectively. Cumulative doses of methotrexate, cisplatin, and carboplatin were also evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were compared using the χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test). Cumulative incidence of death due to infectious causes was estimated and compared between three subgroups of survivors, which included survivors who had undergone splenectomy; survivors who had not undergone splenectomy but received splenic radiation (stratified in dose categories of 0.1 to 9.9 Gy, 10 to 19.9 Gy, or ≥ 20.0 Gy); and survivors who had neither splenectomy nor radiotherapy, with all other causes of death considered as competing risks. Cumulative incidence curves were compared using the method proposed by Gray.25

Among survivors, association of infection-related mortality with treatment exposure was evaluated using piecewise-exponential models, first without adjustment (unadjusted analysis), followed by adjustment for attained age as cubic splines, sex, race, age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, number of chronic health conditions, CED, and occurrence of SMN or late recurrence (time-dependent variable) to estimate adjusted relative rate (RR), 95% CIs, and P values. Absolute excess risk per 1,000 person-years was calculated as (observed number of deaths − expected number of death)/person-years × 1,000, where the expected number of deaths were calculated using mortality rates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).26

RESULTS

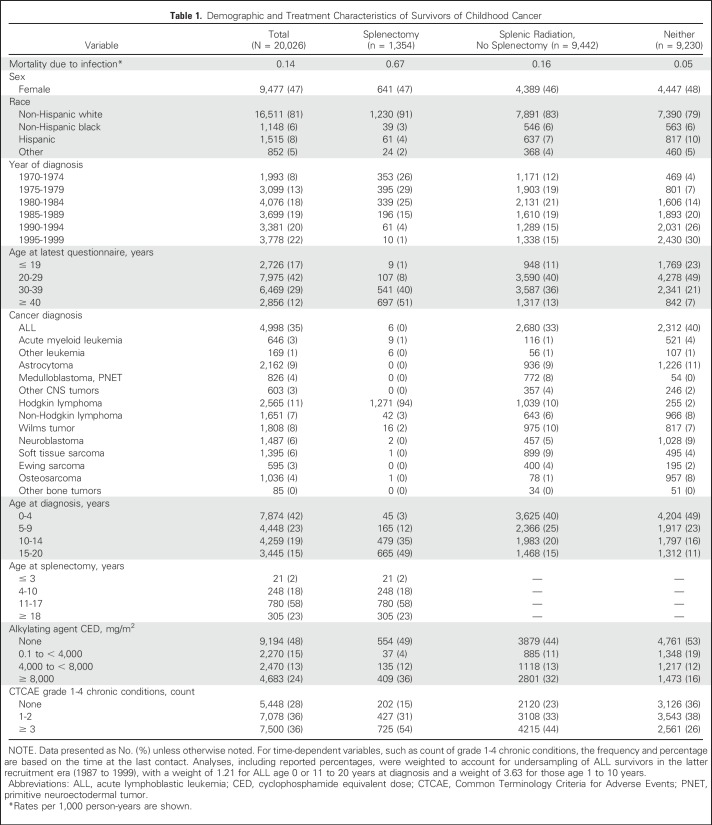

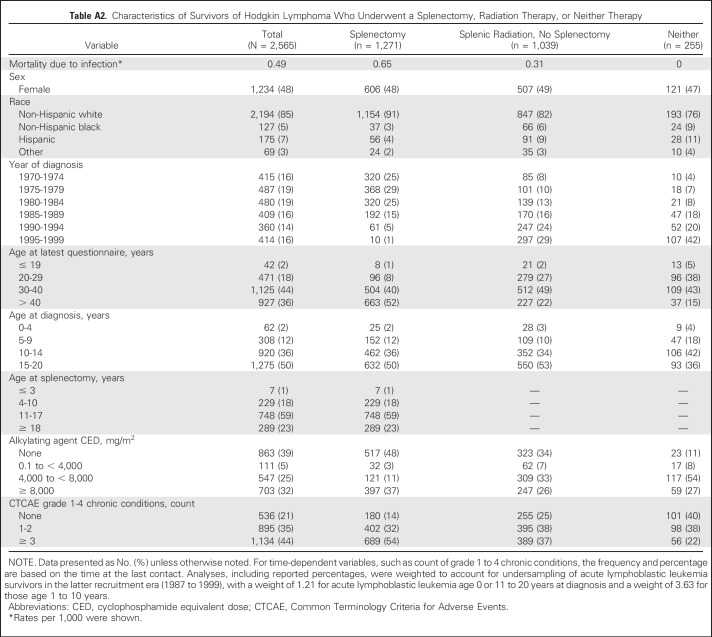

Among 24,355 survivors who completed the baseline CCSS survey, complete data for splenectomy, radiotherapy, and vital status were available for 20,534 (Fig 1). After excluding survivors who received total body irradiation, 20,026 survivors were included in the current analysis (Table 1), with 1,354 survivors (6.8%) who underwent splenectomy and 9,442 (46%) receiving direct or incidental splenic radiation without splenectomy. Median age at diagnosis was 7.0 years (range, 0 to 20 years), and median follow-up was 26 years (range, 5 to 44 years). Ninety-four percent (n = 1,271) of splenectomies were performed in association with HL, suggesting that staging laparotomy for HL was the most common indication. Splenectomies were also performed in association with non-HL, leukemia, Wilms tumors, neuroblastoma, and osteosarcoma (n = 83). Given the high frequency of splenectomy for survivors of HL, descriptive characteristics of these survivors are provided (Appendix Table A2, online only). For each splenic radiation dose group, the top three diagnoses were 0.1 to 9.9 Gy (n = 7,906): leukemia (2,802; 35.4%), CNS (1,997; 25.3%), and soft tissue sarcoma (814; 10.3%); 10 to 19.9 Gy (n = 1,022): kidney (435; 42.6%), HL (268; 26.2%), and neuroblastoma (82; 8.0%); and ≥ 20 Gy (n = 514): kidney (249; 48.4%), HL (90; 17.5%), and neuroblastoma (65; 12.7%).

Table 1.

Demographic and Treatment Characteristics of Survivors of Childhood Cancer

Late infection-related mortality occurred in survivors undergoing splenectomy, receiving splenic radiation, or neither of these therapies at rates of 0.67, 0.16, and 0.05 per 1,000 person-years, respectively (Table 1). Among survivors of HL, the infection-related mortality rate for those who underwent splenectomy was 0.65 per 1,000 person-years (Table A2).

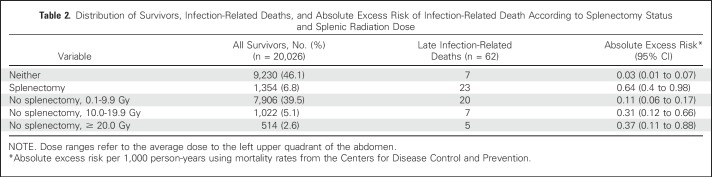

A total of 62 late deaths were attributable to infection, with 55 occurring in survivors who had undergone splenectomy or received splenic radiation (Table 2). Of these, 20 were attributable to sepsis/bacteremia and 42 to pneumonia. No deaths were attributable to meningitis. Six deaths (9.7%) occurred at ≤ 19 years of age, 17 (27.4%) age 20 to 29 years, 13 (21%) age 30 to 39 years, 15 (24.2%) age 40 to 49 years, and 11 (17.7%) age ≥ 50 years. Mortality due to sepsis only was also examined, and although a trend similar to that observed in Table 2 was noted with increasing risk observed among asplenic survivors and those receiving increasing dose of splenic radiotherapy, a small number of events (including no events in the Neither and ≥ 20-Gy groups) precluded additional analysis (data not shown).

Table 2.

Distribution of Survivors, Infection-Related Deaths, and Absolute Excess Risk of Infection-Related Death According to Splenectomy Status and Splenic Radiation Dose

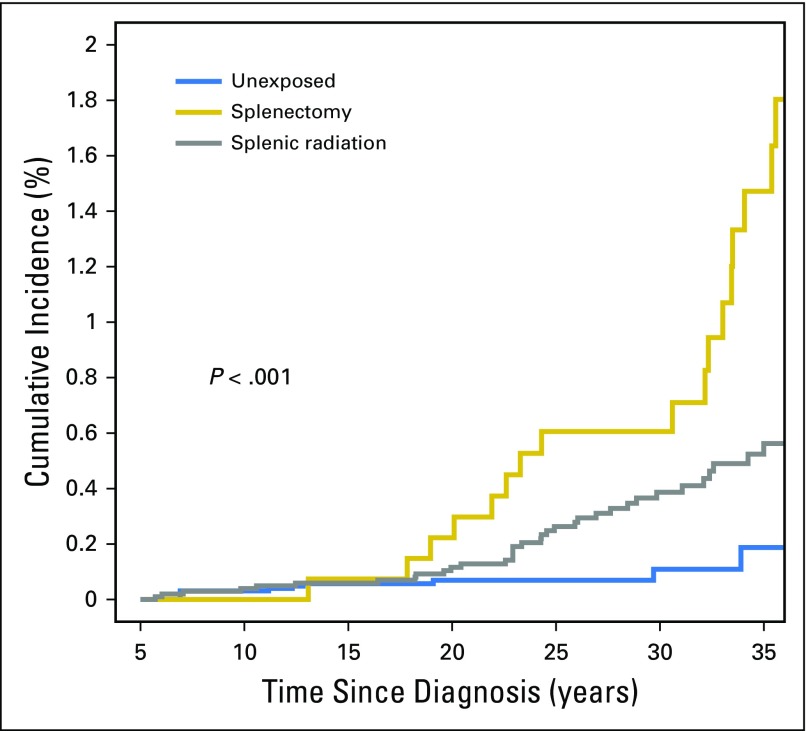

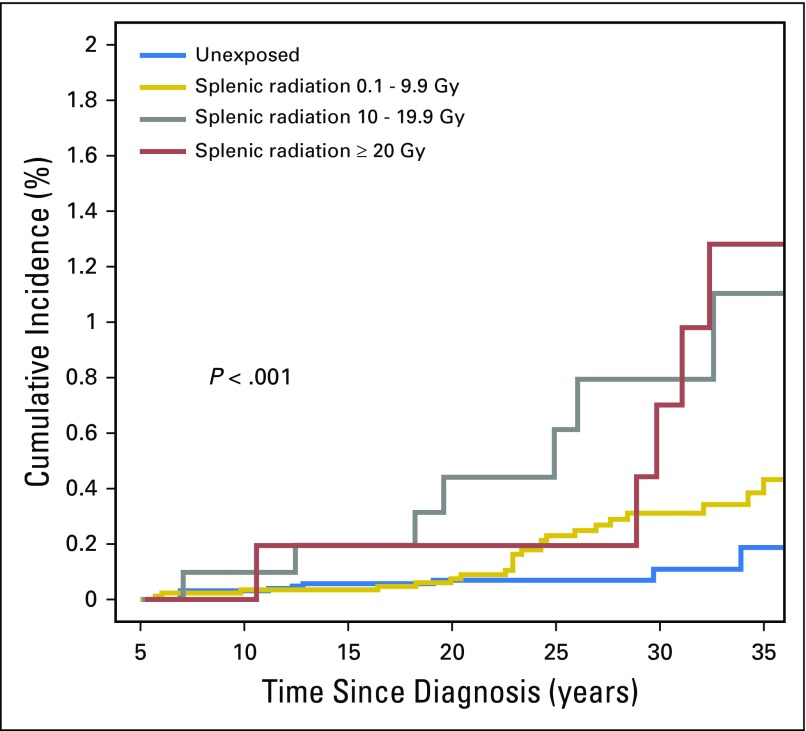

Cumulative incidence of late infection-related mortality at 35 years was 1.5% (95% CI, 0.7% to 2.2%) for those who underwent splenectomy, 0.6% (95% CI, 0.4% to 0.8%) for those receiving splenic radiation, and 0.2% (95% CI, 0.01% to 0.4%) for those who received neither intervention (Fig 2). Stratified by splenic radiation dose, the cumulative incidence of late mortality due to infection at 35 years was 0.4% (95% CI, 0.24% to 0.63%), 1.1% (95% CI, 0.2% to 2%), and 1.3% (95% CI, 0.2% to 2.4%) for survivors who received 0.1 to 9.9 Gy, 10.0 to 19.9 Gy, and ≥ 20.0 Gy, respectively (Fig 3).

Fig 2.

Cumulative incidence of late infection-related mortality among survivors undergoing splenectomy or splenic radiation or those unexposed to either treatment.

Fig 3.

Cumulative incidence of late infection-related mortality among survivors receiving splenic radiation doses of 0.1 to 9.9 Gy, 10.0 to 19.9 Gy, or ≥ 20.0 Gy.

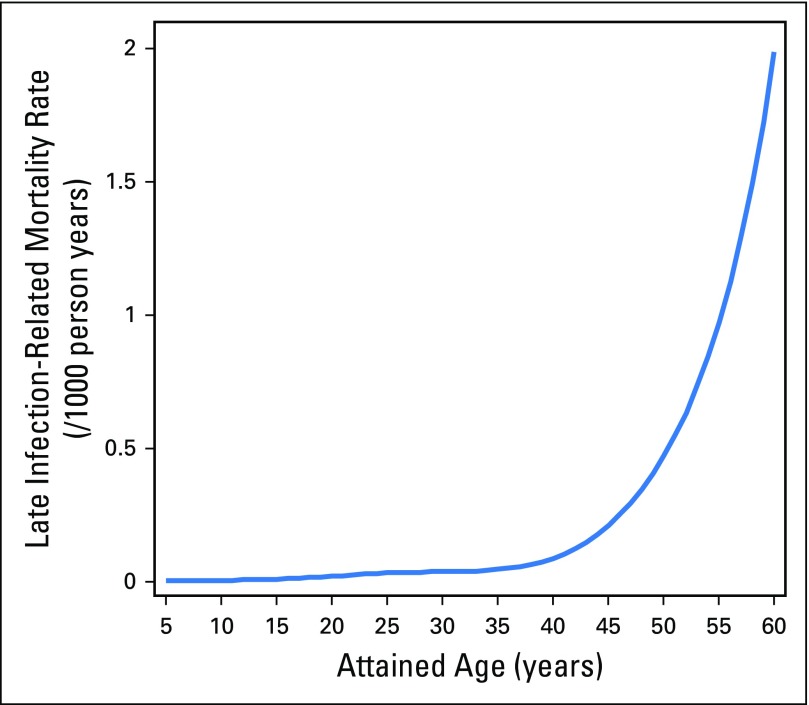

Given that the slopes of the cumulative incidence curves displayed in Figures 2 and 3 seem to increase at year 20 and beyond, we sought to further assess the relationship between attained age and infection-related mortality. We graphically displayed the predicted rate of infection-related mortality by attained age (for survivors with the following set of covariate values: race = white, sex = male, diagnosis age = 10 to 14 years, diagnosis era = 1980 to 1984, splenectomy = no, number chronic grade 3 to 4 conditions = 0, alkylating agent dose = none, and SMN/recurrence = no) on the basis of the previously mentioned piecewise-exponential model. Attained age and rate of infection-related mortality seemed to be highly correlated, with the latter increasing exponentially with increasing attained age, particularly after age 40 years (Appendix Fig A1, online only).

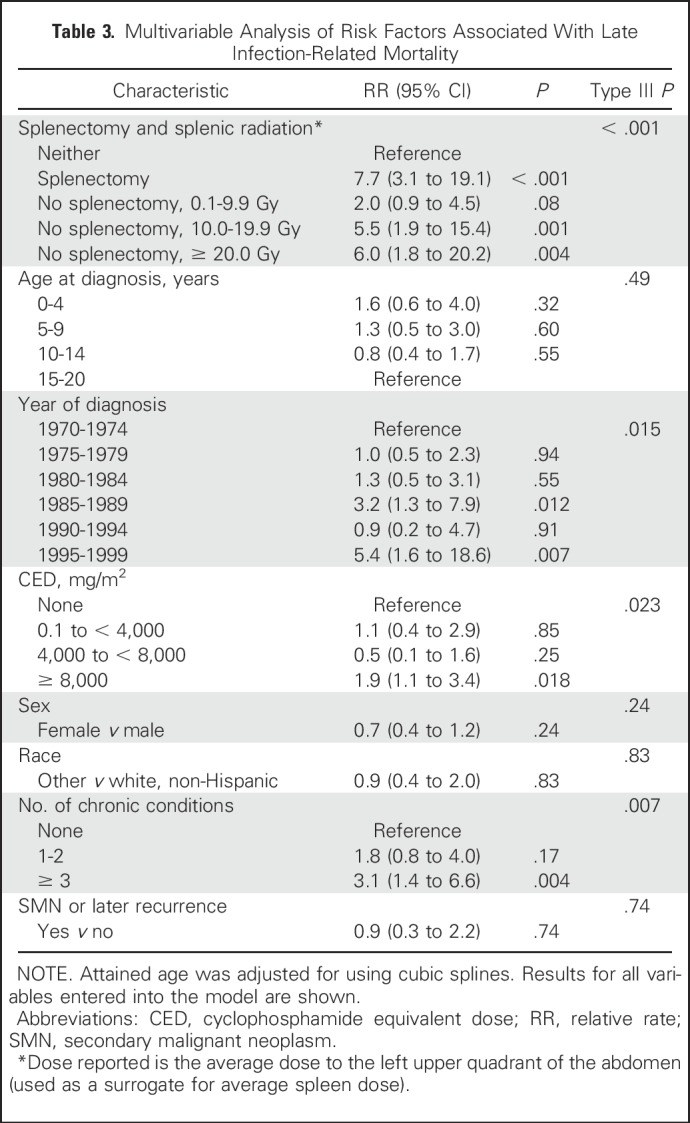

When adjusted for age at diagnosis, attained age, sex, race/ethnicity, number of chronic health conditions, and occurrence of SMN/late recurrence, splenectomy (RR, 7.7; 95% CI, 3.1 to 19.1; P < .001), increasing splenic radiation dose (0.1 to 9.9 Gy: RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 0.9 to 4.5; 10 to 19.9 Gy: RR, 5.5; 95% CI, 1.9 to 15.4; ≥ 20 Gy: RR, 6.0; 95% CI, 1.8 to 20.2), and CED ≥ 8,000 mg/m2 (RR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.1 to 3.4) were independently associated with increased risk of late infection-related mortality (Table 3). Increasing dose of anthracyclines, methotrexate, cisplatin, or carboplatin was not associated with the outcome.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis of Risk Factors Associated With Late Infection-Related Mortality

DISCUSSION

Within the CCSS cohort, we identified that risk for late infection-related mortality among survivors of many different malignancies is significantly increased, not only after splenectomy but also after splenic radiation. Notably, we observed increased risk for late infection-related mortality at lower doses of splenic radiation (10.0 to 19.9 Gy) than previously reported.1-3

The CCSS is a large and diverse cohort representative of the US population of long-term survivors of childhood cancer.13 Many survivors underwent splenectomy or were treated with radiotherapy with a broad spectrum of splenic doses. Thus, this cohort provides a unique opportunity to study long-term outcomes after these exposures. As providers continue to optimize care for survivors of cancer, these findings identify a population not previously believed to be at increased risk for late, treatment-related mortality. These findings should be incorporated into long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood cancer and guide providers to reduce the dose to the spleen from radiotherapy whenever possible.

Current CDC guidelines for the care of asplenic individuals include ensuring administration of appropriate immunizations,27 use of antibiotics prophylactically during childhood, and prompt evaluation for febrile episodes.28 However, there remains a gap in understanding the long-term effect on health and risk factors associated with impaired splenic function and how these individuals should be managed over a lifetime. The findings herein begin to address some of these gaps, particularly with respect to the effect of radiotherapy on impaired splenic function and risk for future infection.

Within this cohort, splenectomy was associated with a nearly eight-fold higher risk for late infection-related mortality. Among those who did not undergo splenectomy, we observed a dose-response relationship between risk of late infection-related mortality and splenic radiation, with even moderate doses of 10 to 19 Gy associated with a 5.5-fold increase in risk for late infection-related mortality in the adjusted model. This observation provides novel evidence that even moderate radiation doses to which the spleen is directly or incidentally exposed increase the risk for late infection-related mortality. Although rates of treatment-related late mortality have improved among more modern survivors, this remains the most common cause of mortality among survivors > 30 years since the time of diagnosis.14,29

The relationship between high-dose splenic radiotherapy and functional asplenia is well established. In 1980, Dailey et al2 reported the case of a survivor of HL whose spleen was within the treatment field, who died 12 years later of pneumococcal septicemia. Autopsy findings revealed a severely atrophied spleen. In the same report, the authors used autopsy data from a small series of patients to show that splenic radiation received during the treatment of HL was associated with reduced splenic weight. The patient in the case report had received 40 Gy of radiation including the spleen. These same investigators later reported reduced splenic size by 99mTc-sulfur colloid scan and increased proportion of pitted erythrocytes among 25 survivors of HL treated with splenic irradiation.30

Recommendations for long-term follow-up of individuals with splenic radiation exposure remain either nonspecific or focused on those who have received higher doses (often considered to be ≥ 40 Gy). The Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-up Guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer recommends that survivors who received splenic doses of ≥ 40 Gy receive timely immunizations against encapsulated bacteria and be evaluated promptly with development of a febrile illness (including obtaining blood cultures and parenteral administration of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as ceftriaxone).28 Regarding administration of pneumococcal, meningococcal, and Hib immunizations, current CDC guidelines recommend that these be considered in adults who have anatomic or functional asplenia.27 Likewise, current American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend appropriate vaccinations for individuals with asplenia or functional asplenia and consideration of prophylactic antibiotics for asplenic children younger than 5 years of age, or for at least 1 year after splenectomy in older children.31 No guidance is given for individuals who have previously received radiotherapy. Current guidelines from the British Committee on Standards in Haematology acknowledge high spleen doses as a risk factor for functional asplenia but do not offer any specific guidance regarding radiation dose or length of time for which individuals remain at risk.32 Consensus statements from other American, European, Canadian, and Australian organizations offer no more specific guidance regarding previous exposure to splenic irradiation and risk for subsequent infection.33-36

With respect to survivors undergoing splenectomy, our findings underscore the long-term infectious risk associated with asplenia. There is general agreement that infectious risk is greatest during the first year after splenectomy. It is also generally accepted that an elevated risk for serious infections remains throughout a lifetime after splenectomy and may increase in advanced-age and elderly individuals.37,38 Our analysis includes only events that occurred beyond 5 years after cancer diagnosis (and splenectomy). We found that undergoing splenectomy was associated with a significantly elevated risk of late infectious mortality (RR, 7.7; overall cumulative incidence of 1.5% at 35 years). In addition, we found within the CCSS cohort that attained age and rate of infection-related mortality are highly correlated, with the latter increasing exponentially with increasing attained age. These findings lend additional support to the notion that asplenia confers a lifetime risk of serious infectious sequelae and one that may increase with advanced age.

Although no consensus exists, it has been suggested, that chemotherapy may influence long-term immune function.39-43 We identified that CED ≥ 8,000 mg/m2 was associated with a modest risk for late mortality, independent of splenic radiation and splenectomy. Other common forms of chemotherapy (anthracyclines and cisplatin) were not associated with the outcome. This observation warrants further study.

There are limitations to this study to be considered. First, there are no means to identify whether survivors were truly rendered functionally asplenic, because information on reduced splenic volume or peripheral blood smears to assess for asplenia (Howell-Jolly bodies, Heinz bodies, pitted membranes) are unavailable. Because objective measures of asplenia are absent, it is possible that the increased risk for late infection-related mortality is multifactorial. It is possible that other unaccounted factors may contribute to some of the increased risk observed, particularly within the lower-dose radiation groups. Nevertheless, the risk of functional hyposplenism after radiotherapy has been well established, and, given the high-risk estimates for radiotherapy and splenectomy, it stands to reason that these factors place survivors at highest risk for infectious death.

In addition, we used the left upper quadrant of the abdomen as a surrogate for splenic radiation. This is a reasonable approximation, given that the spleen is within the left upper quadrant and the doses were stratified in fairly wide, 10-Gy dose groups, making misclassification unlikely. Other limitations include the inability to precisely determine whether survivors received antibiotics or vaccinations and/or whether they may have experienced nonlethal infectious sequelae. Inability to identify survivors who may have experienced serious but nonlethal infections may result in an underestimation of the true effect of asplenia and impaired splenic function on the development of future infections. The lack of precise information with respect to antibiotic and vaccine administration precludes our ability to comment on the effectiveness of these practices in this population. Nevertheless, appropriate immunization against encapsulated bacteria and management of febrile illness with close monitoring and early initiation of antibiotic therapy in asplenic individuals have historically been associated with reduction in the occurrence of severe infections. It stands to reason that the importance of these practices should be emphasized for survivors of childhood malignancy with absent or poorly functioning spleens.

In summary, examination of this large cohort of survivors of cancer reveals that both splenectomy and radiotherapy delivered to a field including the spleen are associated with increased risk of late infection-related mortality. This risk may be potentiated with advancing age. Furthermore, among individuals receiving splenic radiation, elevated risk of mortality exists with lower spleen doses than previously believed. Radiation therapy treatment planning guidelines for contemporary radiation therapy should consider adding recommendations to minimize the dose to the spleen where possible (eg, avoid beams entering through the spleen, set dose constraints during treatment planning, use of proton therapy, and so on). Future guidelines for care of individuals with asplenia or who are at risk for functional hyposplenism should consider these findings that identify a high-risk population for late mortality. Finally, additional efforts are needed to determine the best manner to treat these individuals throughout a lifetime with respect to immunization and antibiotic administration.

Appendix

Fig A1.

Infection-related mortality rate plotted against attained age from the multivariable model (Table 3). The rates shown are for survivors with the following set of covariate values: race = white, sex = male, diagnosis age = 10 to 14 years, diagnosis era = 1980 to 1984, splenectomy = no, number of chronic grade 3 or 4 conditions = 0, alkylating agent dose = none, and SMN/recurrence = no, on the basis of the piecewise-exponential model.

Table A1.

Sepsis-, Meningitis-, and Pneumonia-Related ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes Used to Identify Survivors Experiencing the Primary Outcome of Late Infection-Related Mortality

Table A2.

Characteristics of Survivors of Hodgkin Lymphoma Who Underwent a Splenectomy, Radiation Therapy, or Neither Therapy

Footnotes

Supported by National Cancer Institute Grant No. CA55727 (G.T.A., Principal Investigator) and by Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant No. CA21765 (C. Roberts, Principal Investigator) to St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 2-6, 2017; and the 15th Annual International Conference on Long-Term Complications of Treatment of Children and Adolescents for Cancer, Atlanta, GA, June 15-17, 2017.

K.C.O. and C.B.W. are co-senior authors.

Listen to the podcast by Dr Schwartz at ascopubs.org/jco/podcasts

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Brent R. Weil, Arin L. Madenci, Wendy M. Leisenring, Gregory T. Armstrong, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Christopher B. Weldon

Provision of study materials or patients: Joseph P. Neglia

Collection and assembly of data: Rebecca M. Howell, Yutaka Yasui, Susan A. Smith

Data analysis and interpretation: Brent R. Weil, Arin L. Madenci, Qi Liu, Rebecca M. Howell, Todd M. Gibson, Yutaka Yasui, Susan A. Smith, Emily S. Tonorezos, Danielle N. Friedman, Louis S. Constine, Christopher L. Tinkle, Lisa R. Diller, Gregory T. Armstrong, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Christopher B. Weldon

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Late Infection-Related Mortality in Asplenic Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Brent R. Weil

No relationship to disclose

Arin L. Madenci

No relationship to disclose

Qi Liu

No relationship to disclose

Rebecca M. Howell

No relationship to disclose

Todd M. Gibson

No relationship to disclose

Yutaka Yasui

No relationship to disclose

Joseph P. Neglia

No relationship to disclose

Wendy M. Leisenring

Research Funding: Merck

Susan A. Smith

Honoraria: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Emily S. Tonorezos

No relationship to disclose

Danielle N. Friedman

No relationship to disclose

Louis S. Constine

Honoraria: UpToDate, Springer, Lippincott

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: IBA

Christopher L. Tinkle

No relationship to disclose

Lisa R. Diller

Stock or Other Ownership: Novartis (I), Amgen (I), Celgene (I), Gilead Sciences (I), AbbVie (I), Roche (I)

Gregory T. Armstrong

No relationship to disclose

Kevin C. Oeffinger

No relationship to disclose

Christopher B. Weldon

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman CN, McDougall IR, Dailey MO, et al. : Functional hyposplenia after splenic irradiation for Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Intern Med 96:44-47, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dailey MO, Coleman CN, Kaplan HS: Radiation-induced splenic atrophy in patients with Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. N Engl J Med 302:215-217, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trip AK, Sikorska K, van Sandick JW, et al. : Radiation-induced dose-dependent changes of the spleen following postoperative chemoradiotherapy for gastric cancer. Radiother Oncol 116:239-244, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens M, Brown E, Zipursky A: The effect of abdominal radiation on spleen function: A study in children with Wilms’ tumor. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 3:69-72, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King H, Shumacker HB, Jr: Splenic studies. I. Susceptibility to infection after splenectomy performed in infancy. Ann Surg 136:239-242, 1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chilcote RR, Baehner RL, Hammond D: Septicemia and meningitis in children splenectomized for Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med 295:798-800, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foss Abrahamsen A, Høiby EA, Hannisdal E, et al. : Systemic pneumococcal disease after staging splenectomy for Hodgkin’s disease 1969-1980 without pneumococcal vaccine protection: A follow-up study 1994. Eur J Haematol 58:73-77, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson A, Enblad G, Gustavsson A, et al. : Long term risk of infections in Hodgkin lymphoma long-term survivors. Br J Haematol 154:661-663, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosner F, Zarrabi MH: Late infections following splenectomy in Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer Invest 1:57-65, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coker DD, Morris DM, Coleman JJ, et al. : Infection among 210 patients with surgically staged Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Med 75:97-109, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hays DM, Ternberg JL, Chen TT, et al. : Postsplenectomy sepsis and other complications following staging laparotomy for Hodgkin’s disease in childhood. J Pediatr Surg 21:628-632, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, et al. : Pediatric cancer survivorship research: Experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27:2319-2327, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, et al. : Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: Prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24:653-663, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. : Reduction in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 374:833-842, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. : The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol 27:2308-2318, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. : Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol 38:229-239, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, et al. : Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:1368-1379, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz PE, Sterioff S, Mucha P, et al. : Postsplenectomy sepsis and mortality in adults. JAMA 248:2279-2283, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stovall M, Weathers R, Kasper C, et al. : Dose reconstruction for therapeutic and diagnostic radiation exposures: Use in epidemiological studies. Radiat Res 166:141-157, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. : Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355:1572-1582, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green DM, Nolan VG, Goodman PJ, et al. : The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 61:53-67, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chow EJ, Stratton KL, Leisenring WM, et al. : Pregnancy after chemotherapy in male and female survivors of childhood cancer treated between 1970 and 1999: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol 17:567-576, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green DM, Liu W, Kutteh WH, et al. : Cumulative alkylating agent exposure and semen parameters in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Lancet Oncol 15:1215-1223, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feijen EAM, Leisenring WM, Stratton KL, et al. : Equivalence ratio for daunorubicin to doxorubicin in relation to late heart failure in survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 33:3774-3780, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray RJ: A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat 16:1141-1154, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : National Vital Statistics System: Mortality Data. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/deaths.htm

- 27.Immunization Acton Coalition : Summary of recommendations for adult immunization. http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p2011.pdf

- 28.Children’s Oncology Group : Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer, version 4.0. http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/pdf/LTFUGuidelines_40.pdf

- 29.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. : Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: A summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27:2328-2338, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner MA, Landmann RG, DeParedes L, et al. : Vesiculated erythrocytes as a determination of splenic reticuloendothelial function in pediatric patients with Hodgkin’s disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 17:338-341, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Academy of Pediatrics: Red Book 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases: Immunization in immunocompromised children. https://redbook.solutions.aap.org/chapter.aspx?sectionId=88187009&bookId=1484&resultClick=1

- 32.Davies JM, Lewis MPN, Wimperis J, et al. : Review of guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen: Prepared on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology by a working party of the Haemato-Oncology task force. Br J Haematol 155:308-317, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Government of Canada : Canadian immunization guide: Part 3 - vaccination of specific populations, immunization of immunocompromised persons. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-3-vaccination-specific-populations/page-8-immunization-immunocompromised-persons.html

- 34.Salvadori MI, Price VE: Preventing and treating infections in children with asplenia or hyposplenia. Paediatr Child Health 19:271-278, 2014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Public Health England : Immunisation of individuals with underlying medical conditions: The green book, chapter 7. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immunisation-of-individuals-with-underlying-medical-conditions-the-green-book-chapter-7

- 36.Australian Government Department of Health : The Australian Immunisation Handbook: 3.3 Groups with special vaccination requirements. http://www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/Handbook10-home~handbook10part3~handbook10-33

- 37.Holdsworth RJ, Irving AD, Cuschieri A: Postsplenectomy sepsis and its mortality rate: Actual versus perceived risks. Br J Surg 78:1031-1038, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagrodia N, Button AM, Spanheimer PM, et al. : Morbidity and mortality following elective splenectomy for benign and malignant hematologic conditions: Analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. JAMA Surg 149:1022-1029, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perkins JL, Chen Y, Harris A, et al. : Infections among long-term survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 120:2514-2521, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fioredda F, Cavillo M, Banov L, et al. : Immunization after the elective end of antineoplastic chemotherapy in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer 52:165-168, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bochennek K, Allwinn R, Langer R, et al. : Differential loss of humoral immunity against measles, mumps, rubella and varicella-zoster virus in children treated for cancer. Vaccine 32:3357-3361, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crawford NW, Heath JA, Ashley D, et al. : Survivors of childhood cancer: An Australian audit of vaccination status after treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 54:128-133, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel SR, Ortín M, Cohen BJ, et al. : Revaccination of children after completion of standard chemotherapy for acute leukemia. Clin Infect Dis 44:635-642, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]