Abstract

In project D.R.E.A.M.S., we propose to develop and assess the feasibility of a novel and intelligent delirium-prevention system to address depression, pain, sleep, activity patterns and emotional states using the Emotiv Epoc+ I 14 Channel EEG”, and HTC Vive VR set.

Keywords: therapy, rehabilitation, new media, VR

I. Introduction

In this paper we will examine the ways in which the processes of therapy and rehabilitation are being changed through the influence of new media technologies. More specifically, we will analyze the emergence of VR and its potential uses in being paired with the brain EEG readers (eg. Emotiv Epoc+ 14 RRG set), as one of the outcomes of the increased use of technology in medicine. Thus offering an opportunity for long-stay hospitalized patients to experience an interactive and engaging reality.

Our hypothesis is that the patients will respond positively to a video game based medical intervention. We will compare the effect of interventions with different types of serious games on the change in pain perception, sedative use, sleep quality and congnitive performance compared to the baseline assessment. We propose the following specific aims:

Aim 1. Assess the effect of serious video games on the pain perception and the need for sedatives. We will examine the association between pain perception and gaming experience in delirium patients. We hypothesize that playing highly immersive games will help lower the awareness of pain and decrease the need for sedatives, which are the risk factors for the development of delirium.

Aim 2. Assess the effect of serious video games on the quality of sleep – We will observe the quality of patients’ sleep after playing highly immersive yet calming video games. We hypothesize that playing calming video games will improve the quality of sleep

Aim 3. Determine the change in cognitive performance after playing serious video games. We will test the patients’ cognition performance during their stay at the ICU unit. We hypothesize that playing structured games will support brain activity in a manner that will prevent cognition deterioration.

The expected outcome of this research is a new cost-effective system to address the prevention of delirium in ICU patients. The proposed system has the potential to improve patient outcomes and decrease hospitalization costs, as well as to decrease the life-long complications and costs by the implementation of proper intervention.

II. SERIOUS APPLICATIONS OF GAMES, SIMULATIONS, AND VIRTUAL WORLDS

Interactive environments are nothing new in the field of medicine. For decades, if not centuries, doctors have used simple games to facilitate patient recovery. But are these new virtual worlds effective as a means of therapy? Are they just a current fad, or do they present the way of the future?

The early evidence, both anecdotal as well as scientific [1], suggest that the interactive virtual environments work. Based on the initial research it seems as if the interactive virtual environments are changing the way in which the patients are treated, and that those exposed to it are having a measurable and concrete increase in recovery time.

But Why?

Based on the studies conducted to date, there seems to be a consensus that the highly interactive virtual environments indeed do improve the patient recovery process [1]. However, it is still not clear why it is so. We propose three different arguments, all of them based on games and interactivity.

A. Argument 1: Games as an Observational Tool

Games are interactive, and this interactivity allows us to continuously gauge patients state as well as progress (reflexes, speed of play, length of play, etc.). Effectively the game becomes a sensor that monitors players feedback in real time. It can contunuosly track and compare data over time, and trigger notfications when anomalies are sensed. Most of these measurements can be obtained by a qualified nurse as well, however such an approach is very difficult to scale. It requires a very low ratio between the nurses and the patients, as otherwise a nurse is not capable of observing with necessary attention, the performance of all the patients.

Technology is working on solving the challenge of scaling nursing. By utilizing games and virtual environments, coupled with advanced Artificial Intelligence, scientists are working on recreating the type of attention that the patients in the past received, while being able to multiply it infmite number or times (as software can be installed on many machines).

B. Argument 2: Context and Emotional Involvement

Creating patient engagement is most successful within a well understood context. Video games and virtual environments provide that context. When we have an emotional stake in the experience, only then does our brain release the chemicals in the amygdala and hippocampus necessary for memory [1]. It is our body’s mechanism that decides which data is relevant and to be transformed into memorized information versus which data is to be discarded. This is why it is easier for us to remember a good novel versus a bad textbook. In school, we often learn the best when there is a presence of fear of the upcoming test. The very emotional involvement in these situations is what makes us engage better in what we experience.

In combining the context and emotional involvement, many have argued that failure is necessary to learn [2]. Thus, creating medical intervention paradigms in which failure is safe, is of the essence to recovery. Games are exactly such environments, which allow for experimentation and failure in a structured and safe format.

C. Argument 3: Participation

One can’t learn to ride a bicycle from a great lecture, the saying goes. And what is true of riding a bicycle may be true of negotiating and strategizing, as well as other similar skills. Often the participation is a necessary ingredient in an experience, that makes us recall it afterwards. The process of converting experiential expertise into linear material such as books and lectures, strips out most of what is valuable in the content to begin with [3].

Many of us have experienced working in a group on a single computer, where on different occasions, different people would ask to take over the mouse and actively participate in creation. Or when a group of children play a video game, often there is a desire in many of the individuals in the group to have the controller and play the game, simply watching it is not enough.

Video games allow for individual participation of all patients, and thus are a valuable tool in the system of medicine.

III. MEDICINE + TECHNOLOGY = D.R.E.A.M.S

Human approach to medicine has undergone a tectonic change in a tremendously short period of time of the second half of the 20th century. Technology has changed the world around us, and more importantly it has changed how we interact with the environment around us. The goal of project D.R.E.A.M.S. is to positively affect ICU patients who have a significant chance of suffering from delirium.

Intensive care units (ICU) collect staggering amounts of clinical information to facilitate patient monitoring and decision making such as multi-channel waveform data, vital sign time series updated each second or minute, alarms and alerts, lab results, staff notes and more [4]. Yet, some type of information may be more difficult to capture as it requires constant observations that are not feasible due to the cost and time constraints. Typically information related to pain, cognitive function, attention, emotion, sleep and activity level is notoriously difficult to collect and objectively assess in timely manner. Paradoxically, from patient and caregiver perspective, such information is often perceived as the most important yet neglected aspect of care [5].

More than a third of patients with delirium would benefit from pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions that are often not administered due to missed diagnosis. Despite recent research in the area, detecting delirium has been challenging [6–8] in practice. Several tools exist for assessing delirium in intensive care unit (lCU) patients, such as the Confusion Assessment Method-Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) or other recent assessment tool such as AWOL [9–11].

Delirium is a common complication with hospitalized patients, with rates of 14–56% and up to 50% in critically ill patients, and up to 80% in surgical patients. It is due to sudden and severe change in brain function, and is characterized by changes in cognition, activity level, consciousness, and alertness. It is estimated that the annual costs of delirium care are about $38 to $152 billion in the United States. ICU delirium is associated with longer ICU length of stay, higher rates of hospital readmission, long-term cognitive impairment and an increased risk of death. However, despite the fact that about a third of patients with delirium can benefit from intervention, detecting and predicting delirium is still challenging in practice [12].

This project expands by adding Digital Arts and Sciences onto the interdisciplinary collaboration between ICU and the pain analytics group, and Biomedical Engineering at the University of Florida. We will implement novel techniques to interpret contextual and temporal information captured by various sensors in the ICU, to provide preventive tools currently missing in clinical practice. Such tools will facilitate implementation of new therapies, such as serious video games and mindfulness techniques. A successful completion of the proposed study will provide internal validation and a working prototype of the system.

Current delirium assessment methods are time consuming and resource-intense, need to be administrated by a trained nurse, and are not able to detect the onset of delirium in real time. Developing a method for automatic detection of delirium can reduce incidence, severity, and duration of delirium in ICU patients. Additionally, using a data driven approach has the potential to advance the field by providing a low cost delirium detection method. Patients who are deemed to be at risk could receive lifesaving interventions.

A. Architecture of BCI Systems

There are three major physical components in BCI system.

Signal Acquisition: Converts electrode signal into digital numeric values that can be manipulated by a computer.

- Signal Processing: Analysis and classification of EEG data.

- Data Pre-processing: Preparation of raw data for further processing.

- Feature Extraction: Selection of useful data for training and classification.

- Data Classification: Translation of data into useful information such as computer commands.

Device Receiver: Response to the commands from Signal Processing.

For the Signal Acquisition, there are 2 types of EEG headsets and head caps. First, single electrode headsets such as the Neurosky Mindwave, are very simple and inexpensive but the data from the single electrode is not enough to classify complex commands [13]. Second, multiple-electrode headsets such as the Emotiv EPOC and standard EEG head cap.

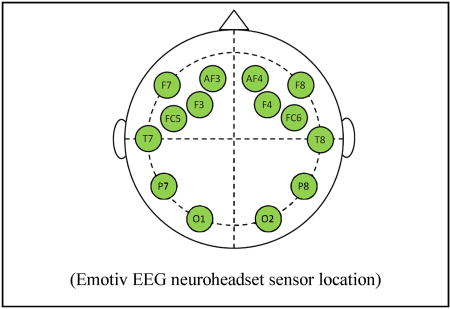

Finally, the Emotiv EEG neuroheadset was chosen as the signal acquisition device, because the cost is not too high, it has multiple electrodes (14 channel) and it provides a full software development kit (SDK) for developing BCI application on PC. This neuroheadset has 14 electrodes located over 10–20 international system positions (10–20 system (EEG) Wikipedia, 2013) AF3, F7, F3, FC5, T7, P7, 01, 02, P8, T8, FC6, F4, F8, and AF4.

For Signal Processor and Device Receiver, we plan to use a VR-ready laptop as signal processor and device receiver. The Emotiv EEG neuroheadset provides a wireless USB that can be plugged into a PC for receiving EEG data from the neuroheadset.

IV. METHODOLOGY – PROCEDURES, FEASABILITY, AND TIMELINE

We plan to prospectively enroll 60 critically-ill patients (20 with hypoactive delirium, 20 with hyperactive delirium and 20 without delirium). Patients will be matched using severity illness scores at the time of ICU admission and will be monitored using our system, for up to 72 hours. The delirium types will be diagnosed using gold standard psychological scales including CAM-ICU, Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98, Memorial Delirium Assessment Schedule, and Delirium Motor Subtyping Scale. Self-report health data is obtained via the “Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System” (PROMIS) measure.

-

Step 1 - Perform patient intervention by engaging the ICU patients with the Virtual Reality content. A series of serious games will be deployed, the patients’ responses will be measured and the resulting data will be analyzed for future iteration and improvement. Evaluate the effects of the patient intervention.

Step 2 - Develop a serious game with a strong commercialization potential, specifically aimed at lowering the development and effects of delirium. The game design will be dictated by the scientific results from Aim 1.

Step 3 - Develop an integrated data collection platform for sensor data, self-reported data, and ERR data.

We have performed a retrospective study of 14,810 patients from a 51,548 cohort (18≥ years), admitted to University of Florida Health ICUs for longer than 24 hours, following all inpatient operative procedures. Delirium was identified by International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes. A Multivariate Logistic Regression model was used to examine association between delirium and baseline characteristics consisting of age, gender, ethnicity, surgery type, emergent surgery, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index, baseline Creatinine, time until ICU admission, and mechanical ventilation. The model had moderate discrimination with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.68 (95% CI 0.66–0.70). Delirium was recognized in our cohort with a prevalence of over 50%, which again highlights the importance of developing novel techniques that can lower the occurrence rate of delirium.

V. CONNECTING THE DOTS

Our hypothesis is that the patients will respond positvely to a video game based medical intervation. Furthermore, our hypothesis is that they will respond the strongest to the VR based experience.

We intend to perform the following testing, divided into five groups:

EEG + survey observation of the test group (no interference)

EEG + survey observation of the group engaged in playing video games on a tablet

EEG + survey observation of the group engaged in playing video games with the Emotiv set only (viewed on the monitor)

EEG + survey observation of the group engaged in playing video games in Virtual Reality

EEG + survey observation of the group engaged in playing video games in Virtual Reality and controlled by an Emotiv set

All of the above tests will be performed in a hospital setting, with a focus on intensive care unit. The initial project will address the patients with a high risk of delirium.

Evaluating these five test groups will give us the initial data in regards to the success of various technologies in treating delirium. Based on the initial results, we will be further developing the most promising technologies. The goal is to arrive to scientific evaluation of the specific types of medical intervetion: mobile games vs. VR vs. Emotiv. Once the most successful technology is identified, we will start developing a series of video games that are targeting specific platfroms, and be of the specific game genre that is prooving to be the best suited for our goals.

Our reseaerch aims to identify most promising technologies for prevenitng delirium in the hospital setting. Followed by the development of proprietery software. We estimate that the whole project will require up to 2 years to implement, followed by the our propriatory video game production time.

VI. LOOK INTO THE FUTURE

As the final goal of our project, we look to connect the Emotiv Epoc EEG set to an HTC Vive VR set. This combination would allow for the bed-ridden patients to move through the virtual reality space solely with their thoughts.

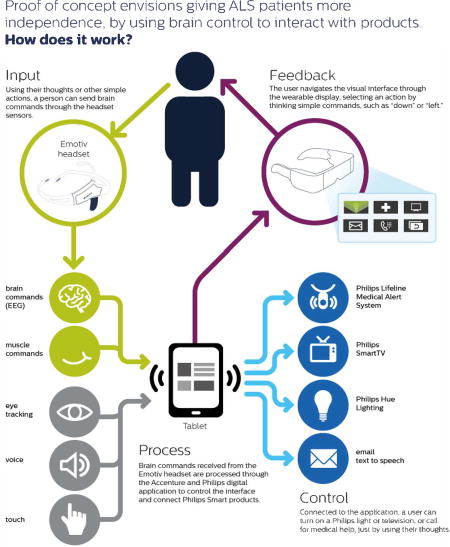

Work in this field has already commenced, and there has been some measurable success in connecting various displays to the Emotiv set. In their 2014 study, Royal Philips (NYSE: PHG; AEX: PHIA) and Accenture (NYSE: ACN) announced proof of concept app to show how ALS patients could command Philips Hue Lighting and SmartTV by using their Emotiv Insight Brainware.

“This proof of concept shows the potential of wearable technology in a powerful new way —helping people with serious diseases and mobility issues take back some control of their lives through digital innovation,” said Paul Daugherty, Accenture’s chief technology officer.

As we move forward we remain conscious of the challenges posed by the early technologies. In this specific case, both the VR sets, as well as the Emotiv Epoc EEG set are quite bulky and may pose some unwanted side effects. Such side effects can be addressed, but never completely eliminated. It is expected that with time, these technologies will shrink in size, and improve in terms of usability; thus enabling further research in a manner that may not even be possible today. It is with this premise that we engage in the project DREAMS, a responsible and technologically advanced exploration of serious games for health.

Contributor Information

Marko Suvajdzic, College of The Arts, Digital Worlds Institute, University of Florida.

Azra Bihorac, College of Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Florida.

Parisa Rashidi, College of Engineering, Biomedical Engineering, University of Florida.

References

- 1.Ledoux J. The Emotional Brain. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keith N, Frese M. Effectivness of error management training: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008;93:59–69. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Klein TA, et al. Neural correlates of error awareness. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1774–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldrich C. The complete guide to simulations and serious games. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer; 2009. [Google Scholar]; Barrie E. PhD diss. Indiana University; 2001. Meaningful interpretative experiences from the participants perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trogrlic Z, et al. A systematic review of implementation strategies for assessment, prevention, and management of ICU delirium and their effect on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19:157. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terry KJ, Anger KE, Szumita PM. Prospective evaluation of inappropriate unable-to-assess CAM-ICU documentations of critically ill adult patients. J Intensive Care. 2015;3:52. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0119-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Jr, Charpentier PA, Leo-Summers L, Acampora D, Holford TR, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mu JL, Lee A, Joynt GM. Pharmacologic agents for the prevention and treatment of delirium in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: systematic review and metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(1):194–204. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trogrlic Z, van der Jagt M, Bakker J, Balas MC, Ely EW, van der Voort PH, et al. A systematic review of implementation strategies for assessment, prevention, and management of ICU delirium and their effect on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19:157. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas VC, Hessler CS, Dhaliwal G, Betjemann JP, Fukuda KA, Alameddine LR, et al. The AWOL tool: derivation and validation of a delirium prediction rule. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):493–9. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terry KJ, Anger KE, Szumita PM. Prospective evaluation of inappropriate unable-to-assess CAM-ICU documentations of critically ill adult patients. J Intensive Care. 2015;3:52. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0119-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luetz A, Heymann A, Radtke FM, Chenitir C, Neuhaus U, Nachtigall I, et al. Different assessment tools for intensive care unit delirium: which score to use? Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):409–18. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cabb42. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Boogaard M. Recalibration of the delirium prediction model for ICU patients (PRE-DELIRIC): a multinational observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez I, Amin T, Jones R, Mongia M. Characterizations of EEG Signals from NeuroSky MindSet Device. Houston, Texas: Rice University; 2012. [Google Scholar]