Abstract

Background

Accountability for ensuring sexual and reproductive health and rights is increasingly receiving global attention. Less attention has been paid to accountability mechanisms for sexual and reproductive health and rights at national and sub-national level, the focus of this systematic review.

Methods

We searched for peer-reviewed literature using accountability, sexual and reproductive health, human rights and accountability instrument search terms across three electronic databases, covering public health, social sciences and legal studies. The search yielded 1906 articles, 40 of which met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (articles on low and middle-income countries in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese published from 1994 and October 2016) defined by a peer reviewed protocol.

Results

Studies were analyzed thematically and through frequencies where appropriate. They were drawn from 41 low- and middle-income countries, with just over half of the publications from the public health literature, 13 from legal studies and the remaining six from social science literature. Accountability was discussed in five health areas: maternal, neonatal and child health services, HIV services, gender-based violence, lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender access and access to reproductive health care in general. We identified three main groupings of accountability strategies: performance, social and legal accountability.

Conclusion

The review identified an increasing trend in the publication of accountability initiatives in Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR). The review points towards a complex ‘accountability ecosystem’ with multiple actors with a range of roles, responsibilities and interactions across levels from the transnational to the local. These accountability strategies are not mutually exclusive, but they do change the terms of engagement between the actors involved. The publications provide little insight on the connections between these accountability strategies and on the contextual conditions for the successful implementation of the accountability interventions. Obtaining a more nuanced understanding of various underpinnings of a successful approach to accountability at national and sub national levels is essential.

Introduction

Accountability has long been a key theme in international development and its related disciplines [1–2]. For health systems specifically, accountability lies at the heart of how power relations in service delivery are negotiated and implemented, whether framed by those in the women’s health movement [3] or by those from multilateral lending organisations [4]. It is also at the core of applying human rights to development and health, whether through their incorporation in economic development [5]; or in preventing and redressing human rights violations [6], or in the monitoring of human rights treaties applied to health [7–8].

Recently, accountability in health has become a key priority at the highest levels of the United Nations system through its engagement with national governments. The Commission on Information and Accountability for Women’s and Children’s Health (CoIA), founded in 2010 as a follow-up to the UN Secretary General’s initiative “Every Woman, Every Child”, recommended that all countries establish and strengthen accountability mechanisms that are transparent and inclusive of all stakeholders [9]. This was reiterated by the Independent Expert Review Group (iERG), which called for strengthening of human rights instruments to improve accountability for women’s and children’s health. The iERG recommended that health ministries prioritise national oversight mechanisms to advance women’s and children’s health with non-state partners at country level [10]. This is echoed in the new Global Strategy on Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030), whereby accountability is recognised as a key action area that harmonizes monitoring and reporting; improves civil registration and vital statistics; and promotes independent review and multi-stakeholder engagement [11]. In 2016, as part of a unified accountability framework, the first report of the Independent Accountability Panel (IAP) further highlighted the need to strengthen rights-based accountability at the national level [12].

Despite increased attention to and demand for accountability in health from multiple and varied global stakeholders, understanding of accountability initiatives for sexual and reproductive health at national and sub-national levels remains limited. Given the multi-disciplinary contributions to understanding accountability, we undertook a systematic review of peer-reviewed literature across disciplinary boundaries. Considering this complexity, at an initial stage in our systematic review, we sought to map the range of accountability strategies and instruments used to address sexual and reproductive health and rights, the low and middle-income contexts in which they were implemented and the resulting documented outcomes.

In the paper, we use the terms “accountability strategy”, “accountability intervention”, “accountability instrument” and “accountability mechanisms”.

An “accountability strategy” is any overarching set of programmes and activities, conducted by governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), grassroots organizations, activist lawyers as well as communities with the intention to enforce or support accountability.

The term “accountability intervention” refers more narrowly to the operational level. Examples include setting up a village health committee, bringing a court case or carrying out a drama workshop to educate villagers on sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR). Interventions are usually delivered within projects or programmes with the objective of supporting accountability.

An “accountability instrument” is the use of particular implementation tools within the context of a given intervention. Examples include patient charter rights or digital health feedback applications.

An “accountability mechanism” is a theoretical explanation of why a strategy or intervention works. Explanatory theoretical mechanisms include collective action, community empowerment, transparency, and enforcement.

Methods

The review methodology was initially structured with a realist and multi-disciplinary intent to ask “what works in terms of accountability mechanisms in the field of sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) at sub-national and national levels, how, why and in which context?”. The review is based on a protocol that was reviewed by an international expert technical committee. We were guided by a meta-interpretation approach [13], which maintains an interpretive epistemology in its analysis, congruent with primary qualitative research. The guiding principles of meta-interpretation are (1) avoiding predetermined exclusion criteria; (2) a focus on meaning in context; (3) using interpretation as unit for synthesis; (4) an iterative approach to theoretical sampling of the studies, and (5) a transparent audit trail to ensure the integrity of the synthesis. It is suitable for this review because it allows capturing the different dimensions relevant to accountability strategies at national and sub-national levels relevant to SRHR accountability.

Search strategy

To capture the accountability strategies across multiple disciplines, we used three search engines: PubMed (health literature), Web of Knowledge (social sciences) and LexisNexis Academic (law). The search terms included combinations of free-text words in TI and /or all fields, depending on the search strategies allowed by the database in question (Table 1 and S1 Table). We refer to the latter for the Boolean operators used for each database search strategy.

Table 1. Search terms.

| Accountability terms | Accountability / accountable (noun/adjective), (public) accountability, (community) accountability, (social) accountability, answerability, enforcement |

| Sexual and Reproductive Health Terms | (Gender-based, sexual, domestic) violence, maternal mortality, maternal morbidity, sexually transmitted infection (STI), HIV, (unintended, unwanted, teenage) pregnancies, (unsafe) abortion, adolescent sexual and reproductive health, adolescent sexual and reproductive rights, obstetric care, respectful childbirth, referral, antenatal care, contraception, family planning, infertility, prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), perinatal mortality, perinatal morbidity, fistula, abuse, female genital mutilation (FGM), child marriage |

| Human rights-sexual and reproductive rights terms | Equality, equity, stigma, non-discrimination, accountability, privacy and confidentiality, informed decision-making, participation, availability, accessibility, acceptability, quality of care, sexual rights, reproductive rights, sexual and reproductive rights, sexual and reproductive health and rights, right to health, women's rights, lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender (LGBT) rights, intersex rights, respect, disrespect |

| Accountability Instruments- Terms | Parliamentary commissions, civil service ombudsman, professional associations, commission on administrative justice, right to information act, consumer forums, health committees, ombudsman services, health commissioners, citizen score cards, right to information, Constitution, annual health summit; public investigators; health sector review; health councils/hospital boards; professional associations (accreditation); health committees; patient/user groups; patients charter; audit bodies; budget committees; ombudsman |

Options to select languages other than English were limited in the three databases. In LexisNexis Academic, two categories of law reviews were available to cover different languages: (1) UK and European journals and (2) Brazilian, Asian law and French language journals and reviews. The UK/European law journals also include journals on legal traditions from LMIC, e.g. Journal of African Law and the Journal of Asian Law. No specific language or country selection options could be made in PubMed and Web of Science.

Study selection

Each abstract was screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in Table 2, covering time period, geographic range, language and publication type.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Criteria | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Timeline | 1994—October 30, 2016 | Before 1994 |

| Countries | Low-and Middle-Income Countries as per Organisation for Economic Cooperation and development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) List of Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) Recipients | All other countries |

| Languages | English, Spanish, French, Portuguese | All other languages |

| Publication type |

|

|

The abstracts that met the inclusion criteria (articles on low and middle income countries in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese published from 1994 onwards—the year of the first International Conference on Population and Development was organised publications on low and middle income countries) were then reviewed to assess if they (1) relate to any accountability strategy or mechanism, (2) relate to a SRHR area or (3) a national level judicial or reconciliation mechanism (such as court proceedings of international war tribunals). The latter included studies reviewing jurisprudence from supreme, constitutional or other national and provincial level courts. To verify fidelity to the inclusion criteria, a sample of 20 abstracts per database were checked for inclusion/exclusion by a second senior researcher. Two researchers discussed the papers for which they had a different opinion until a consensus was reached.

After the full text review, articles were further excluded based on the exclusion criteria (e.g. articles related to global and regional accountability mechanisms). We present the papers that were included in S2 Table.

Data extraction

The review question guided the data extraction. Categories included in the data extraction include: (1) author; (2) SRHR issue; (3) year of publication; (4) number of citations (Google Scholar); (5) year of intervention; (6) original language; (7) funding source; (8) study setting; (9) type of study; (10) accountability type according to the article or as deduced by the researcher; (11) accountability relationship (from whom to whom); (12) accountability strategy and implementation instrument; (13) level at which strategy is supposed to work; (14) purpose (why?); (15) lessons learned; (16) reported outcomes; (17) mechanisms; (18) equity effects; (19) description of the intervention or action; (20) scale of the intervention or action; (21) target population and finally (22) the actors involved in the accountability strategy.

Data analysis

Since this review covers several disciplines (public health, social sciences, legal studies) with different disciplinary standards for writing and quality appraisal, it is difficult to apply a single framework to assess quality across the cases. Legal reviews, for instance, apply a critical (post-positivist) paradigm and typically do not provide a methodology section. Other studies included do not neatly distinguish between reporting and interpreting results. To gauge quality across the papers, we applied the principles of data quality appraisal for qualitative research [14] and used “Not applicable (NA)” when criteria were not applicable (see S3 Table).

Narrative synthesis [15] was used to summarize results and numerical frequencies per category were calculated, whenever this was applicable. Thematic analysis was used to examine the different categories of accountability strategies that emerged.

Results

Study selection

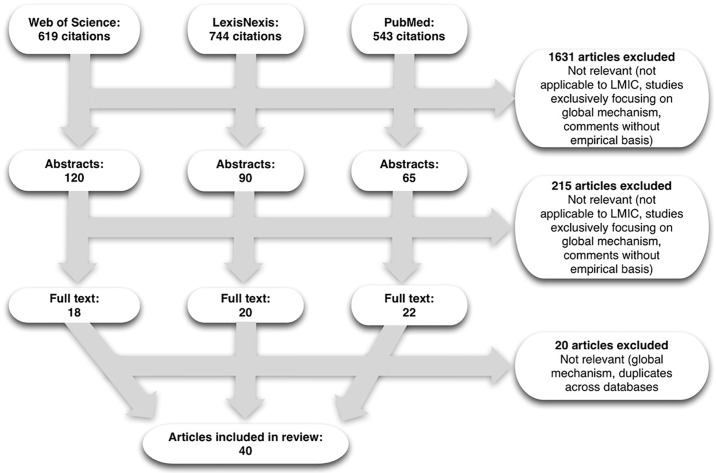

A total of 1,906 articles were found when the search terms were applied to the three databases. On application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1,631 abstracts were excluded. Further review of the 275 included abstracts led to sixty articles downloaded for a full-text review: 18 articles were retained from Web of Science, 20 articles from LexisNexis Academic, and 22 from PubMed. The articles came from public health, legal studies, political science, history, social psychology, anthropology, critical theory, ethics, health services management, clinical sciences, public administration, conflict studies, transitional and restorative justice studies, development and humanitarian studies. This underscores the need for an interdisciplinary approach to understand and examine the different aspects related to accountability in health. After the full text review, twenty out of sixty articles were further excluded resulting in the final selection of 40 articles documenting experiences related to accountability for SRHR at national and subnational level in low and middle-income countries between 1994–2016 (Fig 1 The PRISMA flowchart, S4 Table and S1 File).

Fig 1. The PRISMA flowchart.

Study characteristics

Of the 41 low- and middle-income countries featured, eighteen articles reported on cases in sub-Saharan Africa, 10 in Latin America, nine in Asia, three in the Middle East/Maghreb and one in Europe. Several countries were represented in multiple articles: India (6 studies), South Africa (5 studies), Nigeria (3 articles) and Guatemala (2 studies). Seven studies were in humanitarian or post-conflict settings (Somaliland, Afghanistan, Haiti, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guatemala and Peru). Nine articles reported on multi-country interventions or used examples from more than one country.

While the search period ran between 1994 and October 2016, the majority of articles were published between 2014 and 2015. A range of disciplines and study designs are included (Table 3). Just over half (21 of the 40) of the publications were found among the literature on public health, and a significant number (13) were found from legal studies. Six were drawn from the social sciences (anthropology, political science, development studies and sociology). While over half were qualitative case studies, only two ethnographies, one action research and two critical study articles were found.

Table 3. Research design by SRHR area.

| Research design | Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health (MNCH) | HIV | Gender-based violence | LGBT access | Reproductive health care in general | Row Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic review | Pattinson et al., 2009 [16] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cross-sectional | Asefa & Bekele, 2015 [17], Rosen et al., 2015 [18] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Case studies, qualitative | Papp et al. 2013 [19], Ding 2015 [20], Hulton et al. 2014 [21], Mafuta et al. 2015 [22], Shayo et al. 2013 [23] | McPherson et al. 2013 [24], Topp et al. 2015 [25] Tromp et al 2015 [26] | Bendana & Chopra 2013 [27] | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Descriptive studies | Freedman 2003 [28], Garba & Bandali 2014 [29], Mathai et al. 2015 [30], Hussein & Okonofua 2012 [31], Scott & Danel 2016 [32], Ouédraogo et al. 2014 [33], Labrique et al. 2012 [34], Ghosh 2011 [35] | 0 | Seelinger 2014 [36], Barrow 2009 [37] | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Policy analysis | Blake et al. 2016 [38], George 2003 [39] | 0 | 0 | Penas Defago & Moran Faundes 2014 [40] | 0 | 3 |

| Ethnography | Behague et al., 2008 [41] | 0 | 0 | McCrudden 2015 [42] | 0 | 2 |

| Legal reviews | Kaur 2012 [43] | Durojaye & Balogun, 2010 [44] | 0 | Khaitan 2015 [45], Miles 2015 [46] | Chirwa 2005 [47], Davis 2008 [48], Nolan 2014 [49], Orago 2015 [50] | 8 |

| Action research | 0 | 0 | Crosby & Lykesy, 2011 [51] | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Critical studies | 0 | 0 | 0 | Lind & Keating 2015 [52] | Rinker, 2015 [53] | 2 |

| Undefined | 0 | 0 | Duggan et al. 2008 [54], Du Toit 2016 [55] | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Column total | 20 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 40 |

In terms of study quality, we found that eighteen papers presented an audit trail, 15 had a sampling process described, and in 15 papers, triangulation, member checking or deviant case analysis was used to ascertain validity. Fourteen out of 40 studies (35%) obtained the highest score for explanatory power, only 6 (15%) obtained the highest score for insider comprehensiveness, 13 (32,5%) did so for the advancement of knowledge and 5 out of 40 studies (12.5%) for detail (i.e. making the study clear for outsiders) (see S5 Table). Eighteen out of 40 studies (45%) displayed some proof of long-term field engagement. Only 11 studies (27,5%) clearly distinguished data from interpretation. Finally, only 9 out of 40 studies (22,5%) displayed some form of reflexivity.

Findings on accountability strategies

We found that that five areas of SRHR were discussed: maternal, neonatal and child health services, HIV services, gender-based violence, LGBT access and access to reproductive health care in general (Table 4).

Table 4. Overview of accountability studies per SRHR area, country, scale and its potential beneficiaries.

| Accountability strategy per SRHR area | Country | Scale | Beneficiaries | Article |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health | ||||

| National Guidelines on attention to women in labour and in delivery | Dominican Republic | National and sub-national | Pregnant women and women in labour in health facilities | Freedman 2003 [28] |

| Creation of national Nigeria Independent Accountability Mechanism | Nigeria | National | Not explicitly mentioned | Garba & Bandali 2014 [29] |

| Introduction policy on confidential inquiry | Nigeria | National | Not explicitly mentioned | Hussein & Okonufua 2012 [31] |

| Development civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) and Maternal Death Surveillance and Response (MDSR) systems and audits | Low and Middle Income | National and sub-national | Pregnant women and neonates | Mathai et al. 2015 [30], Scott and Danel 2016 [32] |

| Development of pregnancy surveillance and registry system | India and Bangladesh | Sub-national | Pregnant women | Labrique et al. 2012 [34] |

| Quality improvement through introduction local perinatal mortality audit tool | South Africa and Bangladesh | Sub-national (health facility level) | Neonates | Pattison et al. 2009 [16] |

| Examination of social and institutional conditions of hospital setting within context of near-miss intervention | Benin | Sub-national (health facility level) | Women who had obstetric emergencies | Behague et al. 2008 [41] |

| Assessment of satisfaction of care through a questionnaire based on 7 categories of disrespect and abuse | Ethiopia | Sub-national (health facility level) | Women who had given birth vaginally | Asefah & Bekele 2015 [17] |

| Exploration of existing social accountability practices related to maternal health | Democratic Republic of Congo | Sub-national (district) | Women | Mafuta et al 2015 [22] |

| Training providers in respectful maternity care | Burkina Faso | Sub-national | Pregnant women and women in labour in health facilities | Ouédraogo et al 2014 [33] |

| Quality improvement of facility-based maternal and child health care through direct observation of provider practices | Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Rwanda, Tanzania | Sub-national (health facility level) | Pregnant women, women in labour and children in health facilities | Rosen et al. 2015 [18] |

| Introduction of MNCH score cards and stakeholder meetings | Ghana | Sub-national (district and region) | Pregnant women, communities | Blake et al. 2016 [38] |

| Introduction of community-based scorecards, dashboards, confidential enquiry and maternal death audits | Ethiopia, Malawi, Tanzania, Nigeria and Sierra Leone | National and sub-national | Pregnant women, communities | Hulton et al. 2014 [21] |

| Introduction of community monitoring for maternal health by NGOs | India | Sub-national (decentralized state level) | Disenfranchised women | Papp et al. 2013 [19] |

| NGO led strategic litigation for violation of Economic and Social Rights (ESR), case of maternal death | India | Sub-national (decentralized state level) | Poor women from lower caste communities | Kaur 2012 [43] |

| HIV | ||||

| Use of the Nigerian Constitution to protect against mandatory premarital HIV testing | Nigeria | National | HIV + people, HIV+ women in particular | Durojaye & Balogun 2010 [44] |

| Introduction of Accountability for Reasonableness model in district priority setting for PMTCT programme | Tanzania | Sub-national (district) | PMTCT programme users | Shayo et al. 2013 [23] |

| Assessment of fairness priority setting within regional HIV/AIDS control programme | Indonesia | Sub-national (regional) | Communities | Tromp et al. 2015 [26] |

| Description of accountability mechanisms within context of scale up of HIV services | Zambia | Sub-national (health facility level) | HIV services users | Topp et al. 2015 [25] |

| Description of planning within the context of scaling up male circumcision | Rwanda | National | Men | McPherson et al. 2014 [24] |

| Gender-based violence | ||||

| Use of the Constitution to enforce protection against sexual violence | South Africa | National | Victims of sexual violence | Du Toit 2016 [55] |

| Implementation of the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (2006) | India | Sub-national (decentralized state level) | Children / girls | Ghosh 2011 [35] |

| Implementation of national reparation policy for victims of sexual violence | Post-conflict Guatemala and Peru | National | Indigenous, rural, poor women | Duggan et al. 2008 [54] |

| Implementation of UN Resolution 1325 through micro-initiatives by NGOs | Post-conflict LMIC (Afghanistan, Haiti, Israel/Palestine, Kosovo, Mongolia, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka | Sub-national | Women | Barrow 2009 [37] |

| Participatory action research on NGO truth telling exercise survivors sexual violence | Post-conflict Guatemala | Sub-national | Women survivors sexual violence | Crosby & Lykesy 2011 [51] |

| Description of accountability strategies for post-conflict sexual violence related to documentation, investigation and prosecution of sexual violence | Kenya, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Uganda | National and sub-nation (police and prosecution units) | Victims of sexual violence | Seelinger 2014 [36] |

| LGBT access | ||||

| (Lack of) Supreme Court protection of ESR | India | National | Not explicitly mentioned | Khaitan 2015 [45] |

| Litigation by NGOs to hold government accountable for ESR violations of disenfranchised groups | India, Uganda, Belize | National and sub-national (national and local courts) | Disenfranchised groups | McCrudden 2015 [42] |

| Strategic litigation by activist lawyers to ensure LGBT rights | Chile, India | National | LGBT | Miles 2015 [46] |

| Strategic litigation by conservative NGOs to suspend implementation national abortion guidelines and LGBT rights | Argentina | Sub-national (provincial courts) | Not explicitly mentioned | Penas De Fago et al. 2014 [40] |

| Use of contradicting policies by policymakers to ensure support for their political agenda | Ecuador | National | Not Applicable | Lind & Keating 2015 [52] |

| Reproductive health care in general | ||||

| Legal case using the Constitution to hold non-state actors accountable for ESR violations | South Africa | National | People living in South Africa | Nolan 2014 [49] |

| Legal case using Minimum Core Approach within Constitution to protect ESR rights of marginalized groups and provide them with minimum essential levels of services | Kenya, South Africa, Colombia | National | Disenfranchised groups | Orago 2015 [50] |

| Legal cases using of Section 26 and 27 of the South African Constitution to ensure access to RH care | South Africa | National | Poor, disenfranchised groups | Bendana & Chopra 2013 [27] |

| Legal case using Constitution for ESR protection | Malawi | National | Disenfranchised groups | Chirwa 2005 [47] |

| The implementation of the protection of ESR under the Somaliland Constitution and the implementation of the national gender policy | Somaliland | National | Disenfranchised women | Bendana & Chopra 2013 [27] |

| Exploration of personal accountability child bearing practices against religious background and state development discourse | Morocco | Individual | Not Applicable | Rinker 2015 [53] |

| Examination of the range of accountability strategies in service accountability for reproductive health | India, Brazil, Bolivia, Bangladesh | National and sub-national | Marginalised groups, communities | George 2003 [39] |

| Litigation on the failure of providing regulation for the determination of parenthood (surrogacy mothers) | China | National and sub-national | Surrogate mothers | Ding 2015 [20] |

What are the main types of accountability strategies in SRHR?

In the 40 studies reviewed, we identified three main groupings of accountability strategies: performance accountability, social or ‘community’ accountability and legal accountability. Performance accountability mainly refers to the internal systems that governments hold service providers and health systems to account (see for instance maternal death surveillance and response (MDSR), VRSC, surveillance, etc.), while social accountability is about citizens holding service providers to account. Articles on both of these types predominantly focused on improving the quality of maternal, neonatal and child health care, and increasing coverage and service utilization.

Fifteen of the publications deal with performance accountability and they increase in number from 2012 onwards [16, 21, 24, 25, 29–35, 56]. As mentioned earlier, these articles related to “internal accountability” strategies in relation to service, managerial, administrative or programmatic issues. Specific accountability instruments included patient or death registration and surveillance systems, as well as staff performance review and disciplinary measures. Several articles stressed the need to guard against accountability measures being cast purely as punitive, and they call for a constructive framing of accountability as a way to improve service delivery [39, 56].

Social or “community” accountability is examined by nine articles. These studies sought to bolster the capacity of communities to demand improved service delivery and provider responsiveness through raising community awareness and voice [21–23, 26, 38–39, 41, 48, 51, 57]. We included the Accountability for Reasonableness studies [22, 25] in this category as they assess community involvement in priority-setting and democratic deliberative spaces through participatory tools and processes. We also included the ethnography of obstetric patients in Benin, as it reveals the factors that hold some patients back from demanding social accountability, as well as the nuanced ways in which others are able to negotiate with providers [41]. Among the specific instruments examined in these studies, are stakeholder meetings, public hearings, and the use of community scorecards and dashboards. More formalized mechanisms, such as village health or health watch committees, citizen charters or efforts to implement right to information legislation, also addressed sexual and reproductive health and rights.

The final thirteen articles related to legal accountability for SRHR (see for instance 27, 36, 40, 43–48, 50–51, 54–55). Broadly speaking, legal accountability is about holding the government accountable to wronged citizens and communities. These studies include investigations of accountability achieved through national legal systems, i.e. strategic or public litigation and tribunals. We can distinguish two sub-themes: one is related to accountability for human rights violations and the second is accountability for upholding constitutional rights. The former considers the violations and (lack of) protection of sexual and reproductive health and rights under a national legal and policy framework. These studies interpret the State’s role as duty-bearer to implement national and sub-national accountability strategies to protect citizen’s economic, social and cultural rights. These tended to be examples of NGOs, both progressive and conservative ones, use of strategic litigation or public interest litigation as an instrument to enforce accountability for infringements of human rights, for example in Chile [46], Argentina [40], China [20], Harayana state in India [43, 45]. In the second sub-theme, accountability for upholding constitutional rights, there was a particular focus on the protection of specific economic, social and cultural rights as outlined in the constitution, namely in South Africa, Nigeria, Malawi, Somaliland and Kenya [27, 44, 47–49, 55].

Furthermore, the studies related to legal accountability detailed how national policies and national legal systems increasingly play a role in delivering accountability [36]. A number of studies revolve around decision-making processes and the implementation of laws, policies, programmes and guidelines [23–25, 26, 37, 54, 55]. Another set of studies focus on civil society organisations, preparing or bringing cases on the violations of sexual and reproductive health and rights before court [35, 40, 42–43, 46, 51]. Finally, a group of studies focuses on the role of the courts and the possibilities within the respective countries’ constitutions to protect access to reproductive health and LGBT access [27, 44–45, 47–50, 55].

What are the reported contexts for SRHR accountability to succeed?

Several of articles identified particular contextual conditions associated with successfully undertaking accountability for SRHR at national and sub-national level. Table 5 categorizes them in terms of broad social structures, governance factors, and core features of the health system. However, few of these contextual descriptions were detailed in nature. Often, context was presented in the background section of the article, without explicit analysis of its contribution to the observed outcomes or linkage to accountability mechanisms. For example, we did not find articles that specifically mentioned the media or the extent of privatization of health services as contextual factors influencing accountability for sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Table 5. Contextual conditions for successful SRHR accountability.

| Reported context conditions | Studies |

|---|---|

| Broad social structure | |

| Societal awareness (e.g. no fear of stigma for victims of SRHR violations) | Seelinger, 2014 [36], Duggan et al. 2008, [54], George 2003 [39] |

| Active civil society and civic culture (advocating for the implementation of SRHR through strategic litigation, amongst other strategies) | Chirwa, 2005 [47], George 2003 [39] |

| Trust in the legal system and the institutions | Bendana & Chopra, 2013 [27], Seelinger, 2014 [36] |

| Governance context (overall political and legal framework) | |

| Democratic space (civil society action is possible) | Miles, 2015 [46], Lind & Keating, 2013 [52] |

| Recognition of the rule of law, reduced impunity (freedom from reprisal when victims report violations) | Bendana & Chopra, 2013 [27], Seelinger, 2014 [36], Duggan et al., 2008 [54] |

| Independent judiciary knowledgeable about human rights and SRHR | Khaitan, 2015 [45], Kaur, 2012 [43], Seelinger, 2014 [36] |

| Adapted legal and policy framework | Scott & Danel, 2016 [32] |

| Health system context | |

| Community participation in the health system | Scott & Danel, 2016 [32], George 2003 [39] |

| Adequately resourced health system (timely budget allocation, adequate human resources) | Scott & Danel, 2016 [32] |

| Motivated health providers and no blame culture in health facilities | Scott & Danel, 2016 [32], Asefa & Bekele, 2015 [17] |

| Robust Health Management and Information System | Mathai et al., 2015 [30] |

| Sound management of the local health system and the health facility, leadership | Freedman, 2003 [28], Blake et al., 2016 [38] |

What are the reported outcomes?

The studies reviewed reported several types of outcomes (See S6 Table). Not surprisingly, few studies were able to document health outcomes due to their study designs. Authors more frequently focused on intermediary outcomes, such as community or health care user empowerment, provider behaviour, broader health systems or changes in legislation, policy or guidelines changes.

Hussein and Okonufua [31] summarize the effects of accountability interventions in maternal health on provider practices. They reported mixed changes in the professional practice of health workers, with better outcomes in multifaceted interventions compared to those focused solely on audit and feedback. Hussein and Okonufua conclude that much uncertainty exists on the effectiveness of audits, with some studies showing no evidence and others revealing inconclusive findings. Concerning changes at the level of national and sub-national levels, both Mathai et al. [30] and Scott and Danel [32] reported an increase in the implementation of maternal death surveillance and response committees, national level confidential enquiry or maternal death review committees. Both Hussein and Okonufua [31] and Pattinson et al. [16] reported on the cost effectiveness of the implementation of maternal death audits in resource-constrained settings. The most substantial cost these studies cited related to data collection and analysis.

Topp et al. [25] and Papp et al. [19] reported positive changes in capabilities of disenfranchised groups. Topp et al. found a positive effect on the empowerment of people living with HIV, while Papp. et al. noted that women’s capability to demand accountability improved. Other reported outcomes found in the review relate to changes in the content of policies or in the pace or progress of implementation. For example, gender laws in Nepal and Sri Lanka were modified [37] as a result of civil society demands, and a court in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh ordered the immediate implementation of maternal death audits [43].

Three studies reported unintended effects. Topp et al. [25] found that the attention given to donor-driven HIV services scaling up in Zambia, which was accompanied by a number of accountability strategies, had a negative impact on quality of care for patients in need of other health services. Lind & Keating [52] found that political capture of LGBT issues masked the lack of progress in other critical ESR obligations. Two articles outlined how religiously affiliated NGOs use strategic litigation to repeal implementation of SRHR laws and related policies [40, 42].

We also assessed whether the studies reported any outcomes related to increased equity. Few studies reported evidence on the equity effects of accountability strategies, though several commented on their potential to influence equity positively. For example, accountability strategies involving civil society organization’s use of strategic litigation and constitutional accountability point to their potential to enforce access for disenfranchised groups [49] and their long-term potential to contribute to the transformation of power dynamics [27, 35, 43–44, 47–48, 50–51, 54]. George [39] notes that despite the transformational intent of participatory approaches, social inclusion and legitimate representation of marginalized groups are not achieved automatically.

Discussion

Our review confirms the rising importance of accountability initiatives in SRHR as signalled by the increase in publications in 2014 and 2015. While the bulk of the articles are drawn from public health, a significant number of articles reflect legal perspectives, as well as contributions from other social science disciplines. The public health studies were largely qualitative case studies, with very few ethnographic, action research or critical studies contributions. The quality of the studies was hard to assess given the diverse disciplinary background of the articles.

The review classed the accountability articles into three main strategies: performance, social and legal accountability. While the majority of articles on performance and social accountability strategies focused on improving service delivery for maternal, neonatal and child health, legal and policy activism aimed at addressing accountability for HIV, GBV and LGBT concerns.

The review confirms the emerging analytic paradigm that treats accountability interventions as situated within complex accountability ecosystems comprised of multiple actors and institutions with a range of roles, responsibilities, interactions, and incentives. These ecosystems operate at multiple levels, from the transnational to the local.

These accountability strategies change the terms of engagement among the actors involved. Our review highlights that accountability is not a ‘one size fits all’ formulation where a set of prescribed tools can be transferred from one setting to another with an expectation of achieving similar outcomes. Rather, the success of accountability strategies is influenced by context-specific factors including power relations, socio-cultural dynamics, and the ability of community to negotiate accountability. Thus, our review’s finding align with analyses of accountability strategies and interventions beyond SRHR [57].

The recommendations made by the Commission on Information and Accountability for Women’s and Children’s Health in 2011 [58] coincide with a rise in publications on performance accountability after 2013. The legal studies reveal a clear use of global legal norms in litigation at constitutional courts or as part of special mechanisms or tribunals, citing, for example, the 1976 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Economic and Social Rights and UN Security Council Resolution 1325. These studies offer suggestive evidence that global normative frameworks are influencing national laws and policies. In these instances, global norms and standards provide transnational legitimacy for reformers seeking to pursue national accountability efforts.

In terms of impacts on health, the bulk of articles focused on MNCH, though several articles documented accountability experiences related to HIV, gender-based violence, LGBT or reproductive health. No published articles were found related to safe abortion, reproductive cancers or family planning, despite the active social movements and the role of litigation supporting policy and programming in those areas.

In terms of specific populations, articles did reflect the experience of reproductive age women, HIV affected populations and LGBT communities. While several articles reported accountability measures for marginalized communities, the specific experiences of adolescents and sex workers were not captured by the studies reviewed. While several articles listed marginalized communities as their main concern, authors tended not to address the equity effects of the accountability strategies being assessed. No publications examined how the accountability strategies addressed structural inequalities and benefits distribution across populations.

Finally, we note certain gaps in the published literature with regards to other types of accountability strategies beyond those in the three categories our review examined. The studies reviewed paid little attention to parliaments, a traditional institution for public accountability in democratic governance models; to national human rights bodies; or to the effects of elections or protest actions. We did not find studies discussing parliamentary committee works such as budget committees, nor parliamentary hearings on sexual and reproductive health and rights. Also absent were references to ombudsman and whistle-blower strategies and administrative sanctioning procedures as accountability instruments. Financial accountability, and related tools such as participatory budgeting, are also missing in the published literature for sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this review is that it gathered articles from diverse disciplines. This has broadened our understanding of accountability ecosystems in SRHR, and particularly of how they change the terms of engagement between the actors involved. A second strength is that the review covered not only specific interventions but also approaches such as civil society action and litigation.

Arguably, this review only represents a sliver of what is happening on the ground as it was limited to the peer-reviewed literature. It therefore necessarily reflects the academic evidence base on accountability in health or other sectors. Much of the evidence related to civil society action in sexual and reproductive health and rights has not been published in peer-review journals. A wider review of accountability in the grey literature would be necessary to address the noted evidence gaps. Nevertheless, limitations will likely remain as documentation of actions by practitioners such as activist civil society organisations is often neither their priority especially given the resource constraints they often face.

Another limitation is related to language: only LexisNexis Academic allowed for selection other languages than English. Finally, there may be some bias in the selection of studies retained in the review, as only 3 sets of 20 abstracts, drawn from the papers selected by each database were checked for adherence to the inclusion/exclusion by a second researcher. We acknowledge this constituted a small sample.

Conclusion

As we note above, our review highlighted the importance of viewing accountability as located within accountability ecosystems. However, the current state of research provides little insight on how SRHR accountability strategies work as part of an accountability ecosystem and under which conditions. This gap is not specific to studies of SRHR, but is a challenge to research on accountability across sectors. We welcome the increased focus on accountability across different dimensions of health, particularly in relation to sexual and reproductive health and rights. However, policymakers and practitioners are often under pressure to identify what appear to be simple solutions, which run the risk of reducing accountability interventions to tokenism or quick fixes. A more nuanced understanding of contextual factors and their impacts on different strategies and processes and the capability of individuals and communities to negotiate accountability lies at the heart of ensuring that accountability efforts affirm sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We much appreciate and therefore wish to acknowledge the inputs and contributions of the following members of our expert advisory panel: Lynn Freedman, Martha Schaaf, Walter Flores, and Susannah Mayhew. We also appreciate the review of early drafts of this paper by Karen Hardee and Ian Askew. Finally, we would like to thank Joanna Baker for her contribution to copy-editing the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This research is supported by the Human Reproduction Programme of the World Health Organization. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the authors’ employers or funders. Vicky Boydell is supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (co-operative agreement no. AID OAA-A-13-00087). Asha George is supported by the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant No 82769). Any opinion, finding and conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the authors.

References

- 1.Ebrahim A. Making Sense of Accountability: Conceptual Perspectives for Northern and Southern Nonprofits. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 2003;14(2):191–211. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schedler A, Diamond L, Plattner MF, editors. The Self-Restraining State Power and Accountability in New Democracies. Boulder, CO., Lynne Rienner; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murthy RL, Klugman B. Service accountability and community participation in the context of health sector reforms in Asia: implications for sexual and reproductive health services. Health Policy and Planning. 2004;19(supplement 1):i78–i86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The World Bank. GINI Index 2013 [November, 21, 2013]. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI/countries/GH-BF-TG-ML-NG-BJ?display=graph.

- 5.Uvin P. On High Moral Ground: the Incorporation of Human Rights by the Development Enterprise Fletcher Journal of Development Studies. 2002;17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Draft Guidelines. A Human Rights Approach to Poverty Reduction Strategies. Draft Publication written by Paul Hunt, Siddiq Osmani and Manfred Novak. Geneva OHCHR; 2003.

- 7.General Comment no.14 The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 12 of the Covenant), 2000.

- 8.Potts H. Accountability and the Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health. Colchester: University of Essex, 2008.

- 9.WHO, UNICEF. Building a Future for Women and Children. The 2012 Report. 2012.

- 10.WHO IERG. Every Woman, Every Child. A post 2015 Vision. The Third Report of the Independent Expert Review Group on Information and Accountability for Women's and Children's Health. 2014.

- 11.Every Woman EC. The Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health (2016–2030) Survive, Thrive, Transform. New York: United Nations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Independent Accountability Panel. Old challenges, New Hopes: Accountability for the Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescent Health. 2016:71.

- 13.Weed M. "Meta Interpretation": A Method for the Interpretive Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2005;6(1). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. British Medical Journal. 2000;320(50). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popay J, Roberts, H., Sander, A., Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC Methods Programme. London: ESRC, 2006.

- 16.Pattinson R, Kerber K, Waiswa P, Day LT, Mussell F, Asiruddin S, Blencowe H, Lawn JE. Perinatal mortality audit: Counting, accountability and overcoming challenges in scaling up in low-and middle-income countries. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2009;107:S113–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asefah A, Bekele D. Status of respectful and non-abusive care during facility-based childbirth in a hospital and health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Reproductive Health. 2015;12(33). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen HE, Lyman PF, Carr C, Rei V, Ricca J, Bazant ES, Bartlett LA. Direct observation of respectful maternity care in five countries: a cross-sectional study of health facilities in East and Southern Africa BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015;15(306). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papp SA, Gogoi A, Campbell C. Improving maternal health through social accountability: A case study from Orissa, India Global Public Health. 2013;8(4):449–64. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2012.748085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding C. Surrogacy Litigation in China and Beyond. Journal of the Law and Biosciences. 2015;2(1):33–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hulton L, Matthews Z, Martin-Hilber A, Adanu R, Ferla C, Getachew A, Makwenda C, Segun B, Yilla M. Using evidence to drive action: A “revolution in accountability” to implement quality care for better maternal and newborn health in Africa International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2014;127:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mafuta EM, Dieleman MA, Hogema LM, Khomba PA, Zioko FM, Kayembe PK, De Cock Buning T, Mambu TNM. Social accountability for maternal health services in Muanda and Bolenge Health Zones, Democratic Republic of Congo: a situation analysis BMC Health Services Research. 2015;15(514). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shayo EH, Mboera LEG, Blysta A. Stakeholders’ participation in planning and priority setting in the context of a decentralised health care system: the case of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programme in Tanzania BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13(273). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McPherson DB, Balisanga HN, Mbabazi JK. Bridging the accountability divide: male circumcision planning in Rwanda as a case study in how to merge divergent operational planning approaches. Health Policy and Planning. 2014;29:883–92. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topp SM, Black J, Morrow M, Chipukuma JM, Van Damme W. The impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) service scale-up on mechanisms of accountability in Zambian primary health centres: a case-based health systems analysis BMC Health Services Research. 2015;15(67). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tromp N, Prawiranegara R, Riparev HS, Siregar A, Sunjaya D, Baltussen R. Priority setting in HIV/AIDS control in West Java Indonesia: an evaluation based on the accountability for reasonableness framework. Health Policy and Planning. 2015;30:345–55. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bendana AC. Women's Rights, State-Centric Rule of Law and Legal Pluralism in Somaliland. The Hague Journal on the Rule of Law. 2013;55:44–73. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freedman LP. Human rights, constructive accountability and maternal mortality in the Dominican Republic: a commentary. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2003; 82:111–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garba A, Bandali S. The Nigeria Independent Accountability Mechanism for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2014;127(1):113–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathai M, Dilip TR, Jawad I, Yoshida S. Strengthening accountability to end preventable maternal deaths. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2015;131:S3–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussein J, Okonufua F. Time for Action: Audit, Accountability and Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in Nigeria African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2012;16(1):9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott H, Danel I. Accountability for Improving Maternal and Newborn Health Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2016;36:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ouédraogo A, Kiemtoré S, Zamané H, Bonané BT, Akiotonga M, Lankoande J. Respectful maternity care in three health facilities in Burkina Faso: The experience of the Society of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians of Burkina Faso International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2014;127:S40–S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labrique AB, Pereira S, Christian P, Murthy N, Bartlett L, Mehl G. Pregnancy registration systems can enhance health systems, increase accountability and reduce mortality Reproductive Health Matters. 2012;20(39):113–7. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39631-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh B. Child Marriage, Society and the Law: A Study in a Rural Context in West Bengal, India. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family. 2011;25(2):199–219. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seelinger KT. Domestic accountability for sexual violence: The potential of specialized units in Kenya, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Uganda. International Review of the Red Cross. 2014;96(804):539–64. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrow A. It's like a rubber band. Assessing UNSCR 1325 as a gender mainstreaming process. International Law in Context. 2009;5(1):51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blake C, Annorbah-Sarpei NA, Bailey C, Ismaila Y, Deganus S, Bosomprah S, Galli F, Clark S. Scorecards and social accountability for improved maternal and newborn health services: a pilot in the Ashanti and Volta regions of Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ijgo.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.George A. Using Accountability to Improve Reproductive Health Care. Reproductive Health Matters. 2003;11(21):161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penas De Fago MA, Moran Faundes JA. Conservative litigation against sexual and reproductive health policies in Argentina Reproductive Health Matters. 2014;22(44):82–90. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(14)44805-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Behague D, Kanhonou LG, Filippi V, Lègonou S, Ronsmans C. Pierre Bourdieu and transformative agency: a study of how patients in Benin negotiate blame and accountability in the context of severe obstetric events. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2008;30(4):489–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCrudden C. Transnational Culture Wars. International Journal of Constitutional Law. 2015;13(2):434–62. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaur J. The role of litigation in ensuring women’s reproductive rights: an analysis of the Shanti Devi judgement in India. Reproductive Health Matters. 2012;20(39):21–30. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39604-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durojaye E, Balogun V. Human Rights Implications of Mandatory Premarital HIV Testing. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family. 2010;24(2):245–65. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khaitan T. Judges Vote to Recriminalise Homosexuality. Modern Law Review. 2015;78(4):672–80. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miles P. Brokering Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: Chilean Lawyers and Public Interest Litigation Strategies. Bulletin of Latin American Research. 2015;34(4):435–50. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chirwa DM. A Full Loaf is Better Than Half: The Constitutional Protection of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Journal of African Law. 2005;49(2):204–41. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis DM. Socioeconomic rights: do they deliver the goods? International Journal of Constitutional Law. 2008;6(4):687–711. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nolan A. Holding non-state actors to account for constitutional economic and social rights violations: Experiences and lessons from South Africa and Ireland International Journal of Constitutional Law. 2014;12(1):61–93. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orago NW. The Place of the “Minimum Core Approach” in the Realisation of the Entrenched Socio-Economic Rights in the 2010 Kenyan Constitution Journal of African Law. 2015;59(2):237–70. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crosby A, Lykesy MB. Mayan Women Survivors Speak: The Gendered Nature of Truth Telling in Postwar Guatemala. International Journal of Transitional Justice. 2011;5(3):456–76. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lind A, Keating C. Navigating the Left Turn. International Feminist Journal of Politics. 2013;15(4):515–33. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rinker CH. Creating Neoliberal Citizens in Morocco: Reproductive Health, Development Policy and Popular Islamic Beliefs. Medical Anthropology. 2015;34:226–42. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2014.922082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duggan C, Paz y Paz Bailey C, Guillerot J. Reparations for Sexual and Reproductive Violence: Prospects for Achieving Gender and Justice in Guatemala and Peru. International Journal of Transitional Justice. 2008;2(2):192–213. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Du Toit L. The South African Constitution as Memory and Promise: An Exploration of its Implications for Sexual Violence. Politikon, South African Journal of Political Studies. 2016;43(1):31–51. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Freedman LP. Human rights, constructive accountability and maternal mortality in the Dominican Republic: a commentary. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2003;83(2):111–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joshi A. Reading the Local Context: A Causal Chain Approach to Social Accountability. IDS Bulletin. 2014;45:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 58.WHO. Keeping promises, measuring results. Geneva: World Health Organization, Commission on Information and Accountability on Women’s and Children’s Health, 2011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.