Abstract

Research on the environmental dimensions of human migration has made important strides in recent years. However, findings have been spread across multiple disciplines with wide ranging methodologies and limited theoretical development. This article reviews key findings of the field and identifies future directions for sociological research. We contend that the field has moved beyond linear environmental “push” theories towards a greater integration of context, including micro-, meso-, and macro-level interactions. We highlight findings that migration is often a household strategy to diversify risk (NELM), interacting with household composition, individual characteristics, social networks, and historical, political and economic contexts. We highlight promising developments in the field, including the recognition that migration is a long-standing form of environmental adaptation and yet only one among many forms of adaptation. Finally, we argue that sociologists could contribute significantly to migration-environment inquiry through attention to issues of inequality, perceptions, and agency vis-à-vis structure.

Keywords: adaptation, climate change, environment, migration, mobility, livelihoods, vulnerability

Introduction

Relocating from challenging environmental settings has been an important survival strategy throughout human history (McLeman 2013a). Today, in the context of a changing global climate, the need for improved understanding of migration's environmental drivers is particularly salient. Indeed, the topic is vital for policy (Black et al. 2011) and also holds substantial interest among the public.

Research on the environmental dimensions of human migration has made important strides in recent years. Yet contributions from a sociological perspective have been limited. Human geographers, anthropologists and scholars focused on livelihood vulnerability and adaptation have predominantly led the charge to better understand natural environment “push” factors as related to migration decision-making and migration patterns. Yet evidence has been “varied and patchy”, with wide ranging methodologies, little theoretical development, and myriad geographic foci (Black et al. 2011: S3). With a now solid and growing body of case study evidence, it is time for sociologists to expand migration-environment inquiry to include issues of inequality, perceptions, and considerations of agency vis-à-vis structure. These are areas where, we argue, a sociological perspective could be particularly useful.

The following review of this emergent body of work reveals that the science of migration-environment connections doesn't yet lead to one central conclusion – and perhaps it never will. Even so, the innovative and impressive body of scholarship offers a useful representation of what can happen when the international research machine is mobilized. This machine includes individual researchers, funding and research organizations, and scholarly outlets – all providing the tools and motivation to move a research agenda forward.

The machine was mobilized by bold projections begun in the 1990s of the number of “climate refugees” – projections reaching as high as 50 million environmental migrants by 2010 (Myers 2002). Such projections were not sufficiently grounded in empirical understanding, in part because very little scholarship examined the environmental aspects of migration decision-making. So researchers responded. Over the past two decades, empirical research on the topic has burgeoned.

Even so, bringing environmental factors to migration theory and research has required innovation. Most secondary data on migration doesn't include measures of environmental conditions, nor provide geographic identifiers that would allow contextual data to be appended. In this way, “putting people into place” (Entwisle 2007) has represented a central challenge for migration-environment theory and research.

Stepping back to summarize an emerging body of research represents an important step in moving science forward. It also represents an opportunity to identify lessons learned as well as gaps remaining with regard to theory, results, and methods. The following review offers this summary with a focus on theory and research on the environmental drivers of human migration. Formal resettlement schemes are not included, nor are the environmental effects of migration in destination areas. With regard to gaps, areas where sociological contributions are particularly critical are highlighted.

Advances Made in Migration-Environment Theory

As early as 1992, the International Organization for Migration reported that environmental degradation was already resulting in large numbers of migrants with the possibility of substantial increases due to climate change (IOM 1992). In that same year, Bilsborrow (1992) put forward an early attempt to theorize the environmental dimensions of migration. He linked demographic changes, namely population growth, with economic motivations for land extensification (increase in food demand) and, therefore, outmigration to rural frontier regions (Bilsborrow 1992). Simple bivariate associations between rural population growth, changes in agricultural land, forest area, and fertilizer use were suggestive of associations in this direction, although coarse, since discussion and analyses focused on the national scale. Presaging lessons learned from more contemporary research, Bilsborrow himself ended with a plea for within-country analyses given that the migration-environment association is dramatically shaped by local socio-political, economic and environmental realities.

Bilsborrow's engagement of Boserup's intensification hypothesis and Davis' multiphasic response led the way for linking migration-environment inquiry with existing theory -- a path of potential use to social scientists today. In response to Malthusian arguments of population growth outpacing agriculture production, Boserup (1965) argued that population pressures may intensify rural land use, yielding greater output. Bilsborrow argued that another response to population pressure could be land extensification -- the expansion of agriculture -- through migration.

Davis' (1963) theory of multiphasic response aimed to explain how rural households adapted to threats to their standard of living due to increases in family size. Per Davis (1963), feasible demographic responses included fertility reduction and postponement of marriage. Building on this theory, Bilsborrow (1992) argued that migration represents another feasible demographic response as households face challenging times.

In an effort to further bridge environmental considerations and classical migration theory, Hunter (2005) reached to, for example, Wolpert's stress-threshold model (1966) and Speare's thoughts on “residential satisfaction” (1974). Environmental factors play a role in many of these classic theories, yet details are sparse. For example, the stress-threshold model notes the potential placement of environmental hazards as a ‘stressor’, while environmental amenities and disamenities were generally considered ‘locational characteristics’ within the ‘residential satisfaction’ perspective. Still, Hunter argued that classic migration theory has much to offer in terms of guidance for the emerging migration-environment literature.

These classic theories cannot, however, sufficiently tackle the nuance required for a thorough consideration of environmental factors. Hugo (1996) argued, for example, that environmental factors act on a continuum ranging from slow onset stresses to rapid onset disasters. Slow-onset environmental change such as drought (Findley 1994) and rainfall variability (Warner & Afifi 2014), can lead to migration (McLeman & Smit 2006) as households aim to change or diversify livelihoods. On the other hand, rapid onset natural disasters can result in long-term displacement (Sastry & Gregory 2014) although in some cases, such as Bangladesh flooding, poverty may constrain migration even under such dire circumstances (Gray & Mueller 2012a). This further demonstrates that theory must effectively integrate the interactions between environmental factors and other migration determinants operating differentially across scales and across time. Other determinants include regional and national socio-economic and political conditions as well as household compositional characteristics.

Also complicating theory is the issue of internal vis-a-vis international migration in response to environmental challenges. Environmental displacement has been more likely to result in internal migration due to the political and socio-economic costs of cross-border moves (Hugo 1996). Yet international migration as a household environmental risk diversification strategy also occurs (e.g. Hunter et al. 2013).

A comprehensive migration-environment theory remains elusive, yet an important step toward conceptualization was recently offered by Black and colleagues (2011) in the interdisciplinary journal Global Environmental Change. The framework is influenced by “Sustainable Rural Livelihoods” (Scoones 1998) through explicit integration of a variety of household capitals including social, physical, and economic. Yet it also considers the continuum of environmental influence, international vs. internal migration, and broader contextual determinants operating at a variety of scales.

Case Studies and Clusters of Findings Emerge

As in the realm of migration theory, the empirical creativity of social scientists became apparent once posed with the challenge of considering environmental dimensions of migration. Some scholars innovatively built on migration and other social data collected prior to the occurrence of unforeseen environmental stressors (Findley 1994). Others identified secondary data sources with sufficient geographic identifiers to allow for appending contextual data (Henry et al. 2003). Some collected primary data in individual areas of stress (Meze-Hausken 2000), while others undertook comparative analyses across a variety of settings (Warner 2011).

Of course, generalization is challenged by the wide variety of theoretical and conceptual frameworks, study settings, methodological approaches, and focal environmental factors. Still, the following represent clusters of findings suggested by the emerging body of case studies.

Environmentally-related migration is often a household strategy to diversify risk

The New Economics of Labor Migration (NELM) theory posits migration as a household strategy of livelihood diversification aimed to minimize risks associated with lack of credit, capital and insurance markets (Stark & Bloom 1985). The motivations of Mexico-U.S migrants, in particular, have often been usefully explained through the NELM framework as households send migrants to garner remittances that diversify household income sources (Lindstrom & Lauster 2001; Massey & Espinosa 1997; Taylor & López-Feldman 2010).

As related to environmental factors, rainfall and temperature stress and change may impact livelihood viability especially in rural settings characterized by agricultural or natural-resource based livelihoods (Eakin 2005). Particularly in settings lacking insurance mechanisms, rural households may allocate part of their labor supply to urban or foreign labor markets (Massey et al. 1993). Indeed, studies in several settings have found that migratory responses to environmental strain appear to be strategies of household risk diversification, consistent with the NELM position.

As specific examples, in rural Cambodia, migration is a replacement strategy for agricultural livelihoods as environmental uncertainty increases perceptions of risk (Bylander 2013). Frequent “hot shocks” in northern Nigeria resulted in an increased probability of migration particularly among men, also supporting a risk diversification strategy (Dillon et al. 2011).

Migrant remittances sent to origin regions play a key role in risk diversification, and some studies have included specific consideration of remittance impact. During the Mali drought noted above, 63% of households relied on remittances from family members for income diversification (Findley 1994). Studies in Ecuador (Gray 2009) and Brazil (VanWey et al. 2012) also suggest that remittances augment agricultural production and investment respectively. Scheffran and colleagues (2011) also raise the possibility of remittances as a support structure and conduit for knowledge and resources for adapting to a changing climate in West Africa. Specifically, through three case studies in West Africa, Scheffran et al. (2011) demonstrate that international emigrants leverage their new-found financial, social, and cultural capitals to help their home communities build wells, irrigation systems, and renewable energy grids.

Drought represents an often-studied environmental stress as related to migration, and has been shown to fuel both long and short term movement in a variety of settings. In some cases, households send family members away to reduce household food demand such as during the drought in Mali in 1983-85 (Findley 1994). In vulnerable drought-prone areas of Ethiopia, highly vulnerable households are more likely to send migrants during periods of famine, some to feeding camps or urban areas (Ezra & Kiros 2000; 2001). In other cases, household members migrate in search of livelihood alternatives such as in Burkina Faso where residents of dry regions are especially likely to engage in both temporary and permanent migration to other rural areas with better agricultural prospects (Henry et al. 2004).

The above examples align with the “environmental scarcity” hypothesis that environmentally-related migration can be due to environmental degradation, variability and/or unpredictability. This reallocation of household labor supply helps alleviate losses from lower natural capital “ex post” (Hunter et al. 2014; Nawrotzki et al. 2013). On the other hand, several migration-environment case studies support the “environmental capital” hypothesis which predicts that the availability of natural resources provides capital that may support migration -- particularly more costly long-distance, long-term or international moves. Such long distance migration has been identified as an “ex ante” strategy, in some cases, designed to spread risk related to future stressors (Riosmena et al. 2013; Stark & Bloom 1985).

Supporting the “environmental capital” hypothesis, in rural Ecuador the availability of land and abundant rainfall -- both reflecting higher natural capital -- tend to increase international migration (Gray 2009; Gray 2010). Similar findings emerge from rural South Africa where households harvest from communal landscapes both for household consumption (eg. wild foods) and for income generation (e.g. baskets/mats for market). Migration appears more common from households in villages with greater access to natural capital reflected by the relative abundance of vegetation on their communal lands (Hunter et al. 2013).

Environmental factors interact with other macro-level determinants to shape migration

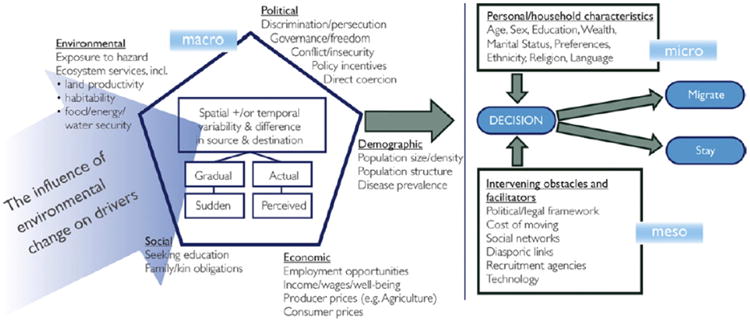

Empirical evidence increasingly reveals that environmental factors shape human migration patterns in combination with numerous other micro-, meso-, and macro-level contextual factors, as reflected conceptually by Figure 1. Macro-level factors include social, cultural, economic, and political structures at multiple spatial and temporal scales. A region's historical-political context also interacts with environmental conditions and change to influence migration.

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework for the drivers of migration as presented by Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A, Thomas D. 2011. The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob. Environ. Change. 21S:S3–11, page S5.

Within this wide variety of contextual forces, several key dimensions have emerged in the literature, including histories of colonialism and related discrimination/persecution, state development policies and programs, as well as international policies shaping, for example, supply/demand, and domestic policies such as land tenure systems. Although we highlight these particular factors, the question of context is prevalent throughout the migration-environment literature.

Colonial histories have shaped settlement patterns, political borders and crop systems in ways that influence contemporary migration-environment associations. For example, in Niger, colonially-imposed cash cropping in the early 1900s led to soil degradation and food shortages that established a pattern of regional, circular migration that continues to characterize today's migration streams (Afifi 2011). In other cases, colonization and state formation brought efforts to sedentarize previously mobile groups that used migration as an adaptation to harsh environments. These efforts, as well as the closing or opening of political borders, have resulted in new patterns of movement in response to environmental change (Barrios et al. 2006; Gila et al. 2011; Marino 2012; Sporton et al. 1999).

Land tenure, often also shaped by these colonial histories, has also emerged as a key variable influencing decisions of individuals and/or households to move as related to environmental conditions. For example, in Guatemala, the combination of soil degradation, lack of available land, and a lack of secure land tenure are drivers of out-migration (López-Carr 2012). In Ethiopia, young people without land are more likely to move in times of environmental stress (Morrissey 2013). And in Benin, land tenure shapes patterns of on-going migration due to migrants' conflicts with landowners in destination areas (Doevenspeck 2011).

Some scholars have argued that global development inequalities are one of the root causes of vulnerability to environmental changes and hazards (Black 2001; Wisner et al. 2004). For example, Lonergan (1998) notes the displacing impacts of large development projects such as dams, irrigation systems, and land reforms. Wisner et al.'s (2004) “pressure and release” model posits neoliberal reforms, structural adjustment programs, and foreign debt as dynamic pressures that influence vulnerability to environmental hazards. Others, including those in the political ecology tradition, have emphasized the importance of local power inequalities in determining how environmental change affects particular groups (Marino 2012; Zetter & Morrissey 2014). In Ghana, for instance, Carr (2005) found that gender and age inequalities in land tenure shaped who benefited from migration.

Finally, scholars are connecting political contexts across scales -- a critically important reflection of contemporary realities. For example, in Botswana, international treaties such as the E.U. Lomé Convention shaped national agricultural policies that in turn affected migration patterns in times of environmental stress (Sporton et al. 1999). Environmental change also affects people through multiple scalar pathways, such as through global commodity prices (Kniveton et al. 2012; Morrissey 2014). These insights regarding the multiple scalar interactions of historical and political context with environmental change represent important contributions to the field.

Household composition and individual characteristics also shape migratory responses to environmental factors

Of course, macro-level factors interact with household and individual characteristics to shape migratory response to environmental conditions. For example, within particular political-economic systems, household life cycle, as well as gender and educational composition, shape migration decision-making.

The importance of household life cycle is usefully illustrated by migration's links to land use decision-making within the Brazilian Amazon. In this region, household demography influences the available labor pool and, therefore, livelihood strategies. Initial migration to the forest frontier tends to occur among younger households that have shorter time horizons and typically, given that shorter horizon, more annual crops (VanWey et al. 2007; Walker et al. 2002). Older, more labor-rich households, are more likely to engage in perennial cropping (Perz 2001). Yet research clearly demonstrates that household demography influences not only farming patterns, but the potential to engage in migration for off-farm employment which, in turn, shapes farming patterns. Households with young adults are more likely to make circular or rural-urban moves as an additional livelihood strategy. Such migration, including among women, generates cash so that agricultural land may be expanded or production increased through hired labor and/or technological inputs (VanWey et al. 2007).

In general, and as described above, non-agricultural labor, often resulting from migration, can provide income to “ex ante” or “ex post” buffer households from environmental shocks. Yet households are not equally likely to engage in the same forms of livelihood migration -- or, indeed, to engage in livelihood migration at all. For example, in response to the 1980s severe drought in Mali, migration was differentiated along socioeconomic lines -- the poorest households engaged in shorter distance migration encompassing shorter time periods (Findley 1994). On the other hand, disasters sometimes undermine the ability of the poorest households to engage in migration as a coping strategy at all, as demonstrated in Bangladesh floods (Gray & Mueller 2012a).

In addition to migration's variation across households, variation also exists as far as who within a household may migrate as related to environmental conditions. In rural Ethiopia, for example, the likelihood of an individual moving in response to drought is greatly shaped by their relationship to the household head -- unrelated household members are more likely to migrate (Ezra & Kiros 2001).

Gender also shapes the environment-migration association, with Bangladeshi women more likely to migrate in response to crop failure and flooding, perhaps due to their less secure access to land within this cultural setting (Gray & Mueller 2012a). In Ethiopia, drought as an environmental force shapes womens' marriage-related migration, reducing such moves by half (Gray & Mueller 2012b). Even so, the opposite occurred in Mali where marriage-related moves doubled during a period of drought (Findley 1994). Also demonstrating gendered migration responses to environmental stress, deforestation in Ghana's central region increased rural-urban migration particularly among young men who are more likely to find new employment opportunities after relocation (Carr 2005).

Educational levels shape employment options and, in this way, also impact the likelihood of migration by specific individuals within a household. Although very few studies have explicitly focused on education's influence on the migration-environment association, recent work in Mali and Senegal provides initial insight. In these settings, when livelihoods come under environmental stress, migration is a livelihood strategy particularly for the lower educated since these individuals tend to be more dependent on agriculture and other environmentally-dependent activities (Van der Land & Hummel 2013).

Social networks shape the migration-environment association

Just as socioeconomic and household contexts shape the migratory response to environmental change, so too does social capital. Indeed, migration researchers have long recognized the centrality of social networks to understanding migration patterns and processes (e.g., Massey & Espinosa 1997). We can look to longstanding migration streams from rural Mexico to the U.S. as an example.

Many regions of rural Mexico have strong migration histories which yield translocal connections between sending and destination communities (Massey et al. 1987). These connections – social capital – reduce the costs of migration by facilitating housing, employment, and other important aspects of settling into destination communities. As related to environmental conditions, in general, drought conditions tend to yield higher levels of Mexico-U.S. migration (Feng et al. 2010) although this is particularly true in communities with strong migration histories (Hunter et al. 2013). In regions lacking such social networks, rainfall deficits actually reduce migration propensities (Hunter et al. 2013).

Other research demonstrates the importance of social networks in a variety of African settings (Doevenspeck 2011; Gila et al. 2011; Jónsson 2010; Sporton et al. 1999) and in rural Cambodia (Bylander 2013). In the case of migration from the small island nation Tuvalu, keeping social groups intact is a key motivation in the face of dramatic decline in living conditions from sea level rise and natural disasters (Shen & Gemenne 2011). A similar concern emerges in rural Alaskan communities facing village relocation due to erosion (Marino 2012).

Promising Developments in Migration-Environment Research

The clusters of research findings highlighted above provide a useful foundation from which migration-environment research continues to move forward. Here we highlight several areas of promising developments.

Moving beyond environmental determinism

Early quantitative exploration of the migration-environment association often sought simply to test for the statistical significance of a particular environmental variable as a predictor of typical household-level migration. The environmental measures themselves varied widely -- some reflecting rainfall recently, historically, or its variability. Some reflected temperature trends, while others focused on migration following natural disasters. In most cases, though, the environmental “signal” was represented on its own without consideration for how the environmental stress may differentially affect individuals and households based on other factors at micro-, meso- and macro scales.

Not surprisingly, results of these early studies varied substantially and the most common answer to the research question “Do environmental factors influence migration?” was actually “It depends.” As noted in the prior section, environmental factors interact with a complex array of contextual factors as well as individual and household level characteristics to ultimately shape migration decision-making. Given this, rather than asking if drought causes migration, for example, researchers are beginning to ask: In what combinations of contexts does drought increase or decrease migration? What are the key micro-, meso-, and macro-scale interactions that predict migration-environment associations? This growing attention to context has helped move the field away from environmental determinism towards a more nuanced exploration of human-environment interactions.

An example of this increasing nuance is Morrissey's (2013) study of the drought-prone highlands of Ethiopia. Morrissey conducted interviews in both sending and receiving communities, paying attention to how environmental changes such as rainfall shortages interact with livelihood strategies, household composition, land tenure, poverty, education, and government food aid policies. In the end, he posits a typology of interactions, which he classifies as additive, enabling, vulnerability and barrier effects that ultimately impact the migration-environment connection. This type of context-specific and nuanced study reflects the promising directions of the field.

Migration is a long-standing form of environmental adaptation, and yet only one among many adaptations

Humans have long responded to environmental conditions through migration, and population movement is increasingly being seen as a longstanding adaptive response (McLeman 2013a). In the U.S., examples can be found of migration from both “environmental hardships” such as the drying of the Great Plains in the 1930s and “environmental calamities” such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (Gutmann & Field 2010).

And yet migration is but one form of adaptation and, with this recognition, migration-environment researchers have begun integrating constructs from the hazards research community. In considering adaptive capacity as related to migration, “vulnerability”, an integral concept within the hazards field, has become a particularly important lens through which to examine migration-environment linkages.

At its most basic definition, vulnerability implies the potential for loss (Cutter 1996). Wisner et al. (2004) further specify that vulnerability consists of those “characteristics of a person or group and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard” (p. 11). With regard to migration and the environment, Marino (2012) uses the concept of “vulnerability” in her examination of an Alaskan community's susceptibility to climate change. In this case she finds that historically rooted power inequalities exacerbate the community's vulnerability to the impacts of erosion and flooding. On the other hand, in their examination of displacement following the Indian Ocean tsunami, Gray and Sumantri (2009) find that traditional views of vulnerability along gender and age lines are only somewhat supported. Instead they find that the degree of damage wrought by the tsunami, as opposed to gender per se, played a key role in influencing mobility.

Resilience represents yet another concept from the hazards community that has been usefully integrated into recent migration-environment research. Resilience is often defined as “the ability of communities to absorb external changes and stresses while maintaining the sustainability of their livelihoods.” (Adger et al. 2002: 358). Scheffran et al. (2012), who hail from a geographic tradition, focus on the impacts that migration can have on contributing to the resilience of communities of origin. Such impacts include the reduction of population pressures on scarce resources, in addition to resilience enhancements due to remittances. Less obvious impacts include the contributions of emigrants in developing community projects within their origin communities (Schreffran et al. 2012).

Even so, some scholars are wary of seeing migration as demonstrating “resilience” or “successful adaptation”; research by de Bruijn and van Dijk (2003) on Fulbe pastoralists in Mali shows a cycle of increasing marginalization where migrants are too poor to send remittances and origin communities suffer from labor shortages followed by new waves of migration. These findings echo concerns that discourses of “resilience” may place a disproportionate responsibility for “self-help” onto vulnerable or marginalized communities and/or people (Reid 2013).

Increasing evidence to critique the simplistic proposition of mass movements of “environmental refugees.”

The growing attention to complexity and context reflects the shifting course of debates over “environmental refugees.” The specter of floods of refugees was raised by some who assumed a direct, causal link between environmental change and forced migration (Myers 2002). Critics, however, argued there was far more to the story (Bilsborrow 1992).

Early on, this debate was characterized by many as the “maximalists” (the proponents of the environmental refugee construct) versus the “minimalists” (the construct's critics) (Suhrke 1994). In many ways, the “maximalist” position resembled a linear “push-pull” model of environmental degradation, which would posit that humans will migrate from environmentally-degraded places towards less environmentally degraded places (Lewin et al. 2012, van der Geest 2011). In contrast, the “minimalists,” and those who emphasized multi-level contextual drivers, argued for greater attention to historical, political, economic, and social contexts (Black 2001; Doevenspeck 2011; Lonergan 1998). They critiqued the maximalist position as static, deterministic, ahistorical, and neo-Malthusian, arguing that the relationship between environmental change and migration is neither linear nor direct.

Fortunately, the field has largely moved beyond polarized debates due to the growing collection of case studies, such as those reviewed above, documenting environmental influences on migration but also revealing difference across settings and complexity in influence. This shift from simplistic conceptual linkages fueling the environmental refugee debate indicates how far the field has come.

Migration-environment data and methodologies are becoming increasingly sophisticated

As illustrated by the wide-ranging research settings reviewed above, much migration-environment research represents geographic case studies, often focused on regions typically characterized by livelihood reliance on proximate natural resources. Studies have tended to engage either quantitative and qualitative methodologies, although quantitative approaches -- often at the household-level - have thus far dominated. Other work taps into historical analogs, such as the Great Plains example, to consider what future climate change might mean for population mobility (e.g. McLeman & Hunter 2010). Migration as related to natural disasters also provides a lens through which to examine the migration-environment connection (e.g. Black et al. 2013), and scholars have also engaged a macro perspective to yield empirical simulations of population movements particularly in light of climate futures (e.g. Curtis & Schneider 2011).

Surveys are a commonly used form of data collection for migration-environment scholarship, and Bilsborrow and Henry (2012) offer methodological recommendations based on years of fieldwork. They review, and provide examples of, three methods of data collection and integration for migration-environment research: 1) merging existing population and environmental data from different sources, 2) adding questions to a survey developed for another purpose such as the Demographic and Health Surveys, and 3) designing and fielding a new survey. A similar overview by Fussell and colleagues (2014) offers additional examples of quantitative research approaches including multi-level and event history models applied in rural South Africa, Burkina Faso and the US Gulf Coast following Hurricane Katrina.

Agent-based models (ABM) have also been promoted as useful tools for examining population-environment interactions, including related to migration (Auchincloss & Roux 2008; Evans & Kelley 2008). An ABM simulates human behavior and allows individuals (active agents) to interact with the environment (passive agent) in complex ways including environmentally-motivated migratory behavior (e.g. Mena et al. 2011). A key strength of ABMs' utility is for the study of feedbacks, adaptations, and nonlinear relationships within coupled natural-human systems (O'Sullivan 2008). In addition, predictions of human behavior can usefully generate understandings of the implications of potential policy interventions (Miller et al. 2010). As an application example, Mena et al. (2011) developed an agent-based model to simulate environmental change (e.g. deforestation) associated with land use patterns of frontier migrant farmers in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon. They combined socio-demographic and socio-economic data from a household survey with longitudinal satellite images of land cover and ultimately created spatially-explicit representation of land use/land cover for the region.

Finally, recent advancements in spatial modeling hold promise as they draw on long-standing scholarship on hazard vulnerability (McLeman 2013b). County-level data for the U.S., merged with spatial estimates of sea level rise reveal the scale of coastal population vulnerability, demonstrating that over 20 million residents of low-elevation coastal zones in the continental U.S. will be affected by sea level rise by 2030 (Curtis & Schneider 2011). Such innovations shed light on potential migration in the face of contemporary climate change. And using geographically-referenced household data merged with satellite imagery allowed Leyk and colleagues (2013) to calculate household-level natural resource availability on communal landscapes in rural South Africa. Their results demonstrate how conclusions regarding migration-environment connections can vary according to study area boundaries (regional, village- or sub-village levels). At the most fine-grained scale, the sub-village level (approximating a community), the environmental capital hypothesis finds support since households with more local natural resources have a higher likelihood of sending a migrant in search of labor opportunities elsewhere.

Gaps Remaining

While acknowledging the substantial, promising inroads made in the past decade within migration-environment scholarship, the topic remains an emergent area of research (McLeman 2013a). Important theoretical, topical and methodological gaps persist, several of which are highlighted here particularly as related to potential contributions from the sociological perspective.

Environmental factors could be usefully integrated within mainstream migration theory, yet how to do so remains a challenge

Human migration is a well-theorized social process, with decades of research guided by a variety of perspectives on the determinants and consequences of migration processes. Yet, environmental factors remain peripheral within mainstream migration theory. Lifestyle migration represents the area most likely to integrate environmental considerations, but with a greater focus on amenity and quality of life factors shaping relocation decisions among relatively affluent and privileged populations (Benson & Osbaldistan 2014). We contend that particularly in the midst of contemporary climate change, environmental considerations should play more centrally into migration theory particularly as related to livelihoods and environmental conditions (both amenities and disamenities) in both urban and rural settings.

Exactly how to “integrate” the environment, however, raises important theoretical questions. We have demonstrated a lack of empirical support for approaches that treat the environment as a simple causal driver. New approaches such as NELM and livelihood perspectives (de Haas 2010) have integrated context but have yet to fully theorize the role of the “environment.” Simply adding the environment as an exogenous variable fails to fully engage with the ways in which human actions shape and are shaped by environmental processes and forces. Oliver-Smith (2012:1063) argues that the failure to recognize the complex mutuality of nature-society relations “lies at the heart of much of the environmental migration debate.” As scholars in diverse fields have argued, re-theorizing nature/culture dualism is a critical task for social theory (e.g. Descola 2013; Freudenburg et al. 1995; Watts 2005) that will have important outcomes for empirical research.

An example of this stumbling block in migration-environment research is the frequent distinction between the “economic” (human) and the strictly “environmental.” The migration-environment literature has focused largely on rural people whose livelihoods are often based in agriculture or natural resource economies. Recognizing this close intertwining, many scholars have used the concept of “environmentally-induced economic migration” (Afifi 2011; Lilleør & Van den Broeck 2011; Scheffran et al. 2011).

Yet even in rural areas, the environment - economic link remains tricky to untangle. Carr (2005) found that environmental degradation from logging in Ghana only mattered for people once logging jobs disappeared. However, Carr noted that people did not move immediately and that age, gender, land tenure, knowledge, and social status affected who moved and who stayed. In Nepal, Massey et al. (2010) found that higher caste Hindus were less affected by environmental change, as their livelihoods were less directly based on environmental occupations. In Mali and Senegal, Van der land and Hummel (2013) found that higher levels of education changed peoples' livelihood strategies, thus changing the environment-economic link. As these diverse findings show, social relations and power structures shape the complex linkages between rural peoples' livelihoods and the environment.

A remaining empirical gap in this literature is to consider how the environment relates to economic drivers in urban contexts, not just rural agricultural settings. The hazards literature could be a useful place to turn as it has offered greater focus on urban vulnerability. Finally, concepts from environmental sociology such as conjoint constitution (Freudenburg et al. 1995) could offer useful theoretical tools for thinking through the mutuality and interrelationships of human livelihoods and their environments.

Consideration of general social theory would aid in generating broader-reaching conclusions regarding migration-environment linkages

As demonstrated by the lengthy debate over the term “environmental refugee” and the more widely accepted idea of a spectrum between forced and voluntary migration (Hugo 1996), the issue of structure vis-à-vis agency is a central theoretical concern for environment and migration scholarship. On the one hand, lifestyle migration can be seen as one reflecting high levels of agency, whereas refugees from natural disasters may face little choice in relocation. Even so, focusing entirely on environmental drivers, such as a natural disaster, ignores the role of political and economic drivers, whereas a more voluntary model of migration, illustrated by lifestyle migration, fails to recognize the role of broader structures (Oliver-Smith 2012).

Despite these gains, research on environment and migration could benefit from greater integration with and elaboration of more general social theory. Giddens' (1984) classic theory of structuration, for example, which posits a dialectical, ongoing relationship between structure and agency, could help theorize how environmental, political, economic, and social structures are both shaped by and shape actors' agency. In a certain sense, the struggle over how to theorize “the environment” in relation to human actions shares substantial features with theories of structure and agency: both are dialectical relations of co-production.

Drawing from broader literatures in social research could help address the relationships of structure/agency and nature/culture. We highlight here several strands of social science scholarship that could greatly improve theorization in environment-migration research. We also indicate empirical gaps in relation to these strands.

Vulnerability and risk frameworks from both the hazards and political ecology research traditions could help to theorize migration and environment. Since its beginnings in the 1980s, vulnerability research has struggled with how to weight the “social” in relation to the “biophysical” (Adger 2006; Bankoff et al. 2004; McLaughlin & Dietz 2008). Models such as Sen's (1981) “entitlements” approach help to demonstrate the importance of social relations of power, whereas models such as Turner et al.'s (2003) “vulnerability/ sustainability” and Cutter's (1996) “hazards of place” help to theorize an integrated socio-ecological system, much in line with the calls made by Oliver-Smith (2012). Finally, the “pressure and release” model of Wisner and colleagues (1994) integrates the hazards and political ecology traditions. This model posits that risk is produced by social vulnerability and physical hazards pressing together. A strength of this perspective lies in its inclusion of historical “root causes” that produce social vulnerability over time. In this way, it provides a useful example of how to theorize macro and meso-level contextual factors in relationship to households' exposures to environmental hazards.

Finally, vulnerability and livelihood frameworks share what de Haas (2010) argues are unrecognized parallels with NELM approaches. These approaches can offer useful tools to understanding how and why people either adapt, move, or stay (Warner et al. 2010). This could help shed light on an important empirical gap of the migration-environment literature, which is to examine immobility. Why some people stay in one place while yet others choose to leave is a question that is critical to understanding the drivers of migration and the human decisions that may occur amidst a complex environmental and social context.

Social theory regarding local power inequalities, the social construction of knowledge, and social cleavages such as gender could also enlighten migration-environment research. Rather than assuming an integrated, neutral “household” that makes decisions democratically, we might ask how peoples' actions and even their “conceptions of the possible” are shaped by local power structures, knowledge, and social categories such as race, class, and gender. Clearly, this is an area where sociology has a great deal to contribute.

Carr (2005), for example, argues that people have very unequal access to resources based on local power structures and social relations. He draws upon Foucault's concept of power/knowledge to explore how peoples' actions “are rationalized as part of or as productive of a field of possible actions” (Carr 2005: 930). In other words, Carr is asking how agents are shaping, and shaped by, structures. Carr contends that by exploring local manifestations of power, we can better understand the links between environment, economy, and society as related to migration decisions, and avoid either overly structural or overly agentic approaches.

In considering the above potential connections to social theory, two empirical gaps in the migration-environment literature become apparent. One empirical gap regards perceptions. How do people perceive and interpret their “environments” and how do these perceptions relate to migration decisions? Researchers could use Foucauldian approaches as mentioned above, or they could turn to literature on the social construction of knowledge and/or the social construction of nature (Berger & Luckmann 1991, Hannigan 2006). Research in Cambodia, for example, found that people's perceptions of agriculture as risky shaped their decisions to migrate, even if they themselves had not experienced income loss (Bylander 2013). This indicates, broadly, that the role of knowledge and the transfer of knowledge need greater exploration.

A second empirical gap regards gender as related to migration-environment linkages. Gender is often a key axis of local power structures and social relations, and scholars are increasingly recognizing its role in environmentally driven migration. However, studies centrally integrating gender are few (Hunter & David 2011). Gray (2010) is an exception as he explicitly looks at the role that natural capital plays in the migration patterns of men versus women. In rural Ecuador, Gray identifies “a significantly gendered migration system in which natural capital plays an important role” (2010: 692). Access to land resources facilitates costly international migration among men. On the other hand, women are more likely to stay when land conditions are marginal, perhaps providing evidence of the undervaluation of women's labor and the overall lower likelihood of female migration (Gray 2010).

And while Massey et al. (2010) examine the role of land productivity and land use change as drivers of migration in Nepal, they find, similarly to Gray (2010) that the gendered division of labor plays an important role in migration patterns. In rural Nepal, men are more likely to collect fuelwood while women collect animal fodder. Their survey results suggest that each additional 100 minutes of time required to collect fodder increases the odds of leaving Chitwan by 14% for women, but has no effect on men's mobility. Agricultural declines affect local movement for both men and women, but long distance migration only for men (Massey et al 2010).

While understanding local power inequalities are crucial for unpacking the locus of “agency,” understanding macro structures at larger temporal and spatial scales are necessary for unpacking “structure.” Moving out from the local scale, theories and methods from historical political economy, world-systems theory, commodity chain analysis, agrarian change and political ecology could help to explore inter-linkages across scales as they relate to migration and environment. We would warn against seeing these global structures as bearing down unilaterally on the local (Hart 2001). Instead, as we have argued with agency/structure and nature/culture, the global and the local too have diverse and dialectic interactions. If this can be kept in mind, many of these theoretical traditions have a great deal to offer migration-environment research, particularly in their attention to linkages across spatial and temporal scales.

One vivid example is Davis' (2001) comparative historical analysis of third world famines at the end of the 19th century. Davis explores the interactions of El Niño climate variations and global economic processes, highlighting the role of imperial trade relations, commodity markets, and state policies. This sort of comparative historical analysis that incorporates attention to environmental factors could also be used to address migration.

Theories of globalization and agrarian change could equally shed light on the interactions of global political economy, environmental change, and “depeasantization” (Magdoff et al. 2000). This could help to link environmental change as it impacts people across various political and geographic scales. The recent drought in California, for example, will affect global commodity prices and agricultural labor opportunities, which will interact with policies such as NAFTA to shape livelihood decisions for Mexican farmers. A bollweevil outbreak in India can destroy a cotton crop and affect commodity prices for West African cotton farmers. These kinds of inter-scalar “environmental” impacts are currently ignored in most migration-environment literature. Social theory that incorporates multiple scalar interactions, including changing economic and political systems over the longer term, may help to incorporate these kinds of interactions.

Critically examine definition of both “migration” and “environment”

As noted above, several summaries of methodological approaches to migration-environment have recently been published (e.g. McLeman 2013b). These summaries raise several important questions including, in a seemingly simple sense, the necessity of clarifying the very definitions of both “migration” and “environment.” As in migration research generally, the definition of population movement requires spatial dimensions through the establishment of boundaries or distance thereby allowing categorization of short- and long-distance moves. Temporal bounds are also necessary -- does “migration” require a 6-month period away from the origin household, 1 year, or some other period of time? What about cyclical seasonal migration where household members circulate between home and short-term labor opportunities? In all cases, the analytical definition of migration must be clearly specified and a more critical examination of what is not included within a particular definition of migration is vital. As many of the studies mentioned above demonstrate, migration is not a static concept and examinations of migration at larger scales may “render invisible” (Massey et al. 2010) important migration patterns at smaller scales. Also lost in a focus on movement is knowledge on immobility, also as noted above.

Complications arise in consistently defining “environment” as well. For example, researchers have explored rainfall through a variety of measurements including precipitation levels in recent years, trends across longer periods, variability, and through measures that reflect relative rainfall as compared to other areas. In some cases, temperature is the focal concern, and also offers a wide variety of measures -- minimum/maximum, mean, variability -- all further complicated by the necessity of choosing the time period for which temperature is calculated (e.g. past year, 2 year, 30 year -- a common window to reflect ‘long-term’). Some researchers measure crop yields (and, related crop failures) to more directly reflect livelihood impacts resultant of challenging environmental conditions such as declining rainfall. Researchers have also examined migration following natural disasters, making use of unforeseen environmental “shocks” to explore the migration-environment connection.

In all, the wide variety of migrations and environments used within migration-environment research certainly challenges the scholarly community's ability to make broad conclusions. Even so, the field has many lessons learned and recent methodological contributions aim to share experiences and enhance the likelihood of more comparable research, and therefore generalizable results, in the future.

Conclusion

Tremendous advancements have been made in the past 20 years on scholarly understanding of the environmental dimensions of migration. Motivated by scientifically untested claims in the early 1990s of mass environmental migrations, researchers began to question how environmental factors shaped migration decision-making. Yet early studies in myriad settings have yielded a variety of answers. Given the known complexity of migration decision-making, it's logical to ask why scholars would think environmental factors would influence migration in the same way in different contexts across different times? Still, those were important initial questions although the research community is now ready to add critical nuance.

Recent results have clearly demonstrated that the migration-environment connection is complex and shaped by micro, meso, and macro-influences. Important inroads have been made with regard to integration of key concepts from many scholarly communities including examining the social dimensions of natural hazards and global environmental change. Concepts such as “vulnerability” and “adaptation” are central to this body of knowledge, although other intellectual bridges remain to be built.

The time is now ripe for sociologists to more centrally engage social theory and issues of inequalities, including inequalities in culturally-shaped livelihood options and natural resource governance and access. Subjectivities related to environmental perceptions and their role in migration are also areas of potential sociological contribution (Adamo & Izazola 2010). Migration-environment research offers important opportunities for advancements in sociological theorizing through extensions to a variety of frameworks including world systems theory (Sassen 2011) and ideas of the conjoint constitution of social and natural phenomena (Freudenburg et al. 1995). Finally, the strengths of qualitative sociologists in ethnographic and comparative scholarship could greatly enhance understanding of the ways in which context and change influence household-level decision-making and well-being while also offering a means of ground-truthing the results of quantitative approaches (McLeman 2013a).

Contemporary climate change has spurred keen interest in this topic among both policymakers and the public. Yet policy and programmatic response to migration shaped by environmental factors tends to favor sudden onset events such as natural disasters where relief efforts have precedence and can be targeted (Mueller et al. 2014). Even so, slow-onset environmental pressures such as drought or heat stress are increasingly likely (IPCC 2013), suggesting important new response mechanisms are required to cope with community strain.

Researchers have thus far been innovative with existing data sources -- linking environmental measures to social data as feasible (Fussell et al. 2014). Yet, as McLeman (2013b) notes, to-date there is no global monitoring system which measures population displacements and environmental changes. Such a system could facilitate and strengthen future migration-environment research, and allow for timely methodological, theoretical, and substantive advancements.

Further, although sociologists have offered important contributions, a non-trivial portion of existing migration-environment scholarship is within cognate disciplines – namely, Human Geography. Yet sociology has much to offer both theoretically and empirically. As research on the environmental dimensions of migration continues to rapidly emerge, sociology ought not get left behind.

Summary Points.

Substantial research progress has been made on migration-environment linkages in the past two decades.

Improved understanding of the environmental dimensions of migration is debunking the overly simplistic popular view of “climate refugees.”

A variety of case studies in many geographic settings are yielding clusters of findings and demonstrating that environmentally-related migration is often a risk diversification strategy.

Migration is a long-standing form of adaptation to environmental change, although migration may not be an option for particularly marginalized households and may further marginalize those most impoverished.

Environmental conditions interact with contextual factors, such as the political economy, to shape migration probabilities.

Household composition and social networks shape households' use of migration as a livelihood strategy in the face of environmental stress.

Links to broader migration or social theory are, unfortunately, few within migration-environment scholarship.

Sociologists have important contributions to make within migration-environment research through integration of questions of structure-agency, gender, inequalities, power and perception.

Future Issues.

Sociologists are poised to more centrally integrate issues of structure-agency, gender, inequalities, power and perceptions into migration-environment research.

Researchers continue to innovatively combine data to further understanding of migration-environment connections, but commitments should also be made to collect relevant data that would be broadly available.

Given the tremendous policy and programmatic importance of migration-environment linkages, particularly in light of contemporary climate change, researchers should be encouraged to better disseminate their findings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD-funded University of Colorado Population Center (grant R24 HD066613).

Contributor Information

Lori M. Hunter, University of Colorado Boulder.

Jessie K. Luna, University of Colorado Boulder

Rachel M. Norton, University of Colorado Denver

Literature Cited

- Adamo SB, Izazola H. Human migration and the environment. Popul Environ. 2010;32(2):105–8. [Google Scholar]

- Adger WN. Vulnerability. Glob Environ Change. 2006;16(3):268–81. [Google Scholar]

- Adger WN, Kelly PM, Winkels A, Huy LQ, Locke C. Migration, remittances, livelihood trajectories, and social resilience. AMBIO J Hum Environ. 2002;31(4):358–66. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-31.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi T. Economic or environmental migration? The push factors in Niger Int Migr. 2011;49(s1):e95–e124. [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss AH, Roux AVD. A new tool for epidemiology: the usefulness of dynamic-agent models in understanding place effects on health. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(1):1–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankoff G, Frerks G, Hilhorst D. Mapping Vulnerability: Disasters, Development, and People. London: Earthscan; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios S, Bertinelli L, Strobl E. Climatic change and rural–urban migration: The case of sub-Saharan Africa. J Urban Econ. 2006;60(3):357–71. [Google Scholar]

- Benson M, Osbaldiston N, editors. Understanding Lifestyle Migration: Theoretical Approaches to Migration and the Quest for a Better Way of Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Berger PL, Luckmann T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Penguin; UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow RE. Population growth, internal migration, and environmental degradation in rural areas of developing countries. Eur J Popul. 1992;8(2):125–48. doi: 10.1007/BF01797549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow RE, Henry SJF. The use of survey data to study migration–environment relationships in developing countries: alternative approaches to data collection. Popul Environ. 2012:1–29. doi: 10.1007/s11111-012-0177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R. Environmental refugees: myth or reality? New Issues in Refugee Research. U. N. High Comm. for Refug; 2001. Work. Pap. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW. Migration and extreme environmental events: New agendas for global change research. Environ Sci Policy. 2013;27(Suppl. 1):S1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Boserup E. The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure. London: Allen & Unwin; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Bylander M. Depending on the Sky: Environmental Distress, Migration, and Coping in Rural Cambodia. Int Migr. 2013 online. [Google Scholar]

- Carr ER. Placing the environment in migration: environment, economy, and power in Ghana's central Region. Environ Plan. 2005;37(5):925–46. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KJ, Schneider A. Understanding the demographic implications of climate change: estimates of localized population predictions under future scenarios of sea-level rise. Popul Environ. 2011;33(1):28–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter SL. Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Prog Hum Geogr. 1996;20:529–39. [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. The theory of change and response in modern demographic history. Popul Index. 1963;29(4):345–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. London: Verso; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruijn M, Van Dijk H. Changing population mobility in West Africa: Fulbe pastoralists in central and south Mali. Afr Aff. 2003;102(407):285–307. [Google Scholar]

- De Haas H. Migration and development: a theoretical perspective. Int Migr Rev. 2010;44(1):227–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00804.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descola P. Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon A, Mueller V, Salau S. Migratory responses to agricultural risk in northern Nigeria. Am J Agric Econ. 2011;93(4):1048–61. [Google Scholar]

- Doevenspeck M. The thin line between choice and flight: environment and migration in rural Benin. Int Migr. 2011;49(s1):e50–e68. [Google Scholar]

- Eakin H. Institutional change, climate risk, and rural vulnerability: Cases from Central Mexico. World Dev. 2005;33(11):1923–38. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle B. Putting people into place. Demography. 2007;44:687–703. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans TP, Kelley H. Assessing the transition from deforestation to forest regrowth with an agent-based model of land cover change for south-central Indiana (USA) Geoforum. 2008;39(2):819–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ezra M, Kiros GE. Household vulnerability to food crisis and mortality in the drought-prone areas of northern Ethiopia. J Biosoc Sci. 2000;32(03):395–409. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000003953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezra M, Kiros GE. Rural Out-migration in the Drought Prone Areas of Ethiopia: A Multilevel Analysis. Int Migr Rev. 2001;35(3):749–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2001.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Krueger AB, Oppenheimer M. Linkages among climate change, crop yields and Mexico–US cross-border migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(32):14257–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002632107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley SE. Does drought increase migration? A study of migration from rural Mali during the 1983-1985 drought. Int Migr Rev. 1994:539–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenburg WR, Frickel S, Gramling R. Beyond the Nature/Society divide: Learning to think about a mountain. Sociol Forum. 1995;10:361–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E, Hunter LM, Gray CL. Measuring the Environmental Dimensions of Human Migration: The Demographer's Toolkit. Glob Environ Change. 2014;28:182–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gila OA, Zaratiegui AU, De Maturana Diéguez VL. Western Sahara: Migration, exile and environment. Int Migr. 2011;49(s1):e146–163. [Google Scholar]

- Gray CL. Rural out-migration and smallholder agriculture in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Popul Environ. 2009;30(4-5):193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Gray CL. Gender, natural capital, and migration in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Environ Plan A. 2010;42(3):678. [Google Scholar]

- Gray CL, Bilsborrow RE. Consequences of out-migration for land use in rural Ecuador. Land Use Policy. 2014;36:182–91. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CL, Mueller V. Natural disasters and population mobility in Bangladesh. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012a;109(16):6000–6005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115944109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CL, Mueller V. Drought and population mobility in rural Ethiopia. World Dev. 2012b;40(1):134–45. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CL, Sumantri C. Tsunami-induced displacement in Sumatra, Indonesia. Presented at Int. Union for the Sci. Study of Popul. Conferr; Marrakech. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann MP, Field V. Katrina in historical context: environment and migration in the US. Popul Environ. 2010;31(1-3):3–19. doi: 10.1007/s11111-009-0088-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan J. Environmental Sociology. London and New York: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hart G. Development critiques in the 1990s: culs de sac and promising paths. Prog Hum Geogr. 2001;25(4):649–58. [Google Scholar]

- Henry S, Boyle P, Lambin EF. Modelling inter-provincial migration in Burkina Faso, West Africa: the role of socio-demographic and environmental factors. Appl Geogr. 2003;23(2):115–36. [Google Scholar]

- Henry S, Schoumaker B, Beauchemin C. The impact of rainfall on the first out-migration: A multi-level event-history analysis in Burkina Faso. Popul Environ. 2004;25(5):423–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo G. Environmental concerns and international migration. Int Migr Rev. 1996:105–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter LM. Migration and environmental hazards. Popul Environ. 2005;26(4):273–302. doi: 10.1007/s11111-005-3343-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter LM, David E. Climate change and migration: Considering gender dimensions. In: Piguet E, de Guchteneire P, Pecoud A, editors. Climate Change and Migration. UNESCO Publishing and Camb. Univ. Press; 2011. pp. 306–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter LM, Murray S, Riosmena F. Rainfall Patterns and US Migration from Rural Mexico. Int Migr Rev. 2013;47(4):874–909. doi: 10.1111/imre.12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter LM, Nawrotzki R, Leyk S, Maclaurin GJ, Twine W, et al. Rural outmigration, natural capital, and livelihoods in South Africa. Popul Space Place. 2014;20(5):402–20. doi: 10.1002/psp.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM/RPG. Migration and the Environment. Geneva and Washington, DC: Int. Organ. for Migr. and Refug. Policy Group; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner GK, Tignor M, Allen SK, et al., editors. IPCC. Climate change 2013: The physical science basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge and New York: Camb. Univ. Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jónsson G. The Environmental Factor in Migration Dynamics: a Review of African Case Studies. Int Migr Inst., Univ. of Oxford; 2010. Work Pap 21. [Google Scholar]

- Kniveton DR, Smith CD, Black R. Emerging migration flows in a changing climate in dryland Africa. Nat Clim Change. 2012;2(6):444–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin PA, Fisher M, Weber B. Do rainfall conditions push or pull rural migrants: evidence from Malawi. Agric Econ. 2012;43(2):191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Leyk S, Maclaurin GJ, Hunter LM, Nawrotzki R, Twine W, et al. Spatially and temporally varying associations between temporary outmigration and natural resource availability in resource-dependent rural communities: a modeling framework. Appl Geogr. 2012;34:559–68. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilleør HB, Van den Broeck K. Economic drivers of migration and climate change in LDCs. Glob Environ Change. 2011;21S:S70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom DP, Lauster N. Local Economic Opportunity and the Competing Risks of Internal and US Migration in Zacatecas, Mexico. Int Migr Rev. 2001;35(4):1232–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lonergan S. The role of environmental degradation in population displacement. Environ Change Secur Proj Rep. 1998 Spring;4:5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Carr D. Agro-ecological drivers of rural out-migration to the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Guatemala. Environ Res Lett. 2012;7(4):045603. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/045603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdoff F, Foster JB, Buttel FH. Hungry for Profit: The Agribusiness Threat to Farmers, Food, and the Environment. New York: Monthly Review Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marino E. The long history of environmental migration: Assessing vulnerability construction and obstacles to successful relocation in Shishmaref, Alaska. Glob Environ Change. 2012;22(2):374–81. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor JE. Theories of international migration: a review and appraisal. Popul Dev Rev. 1993;19(3):431–66. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Axinn WG, Ghimire DJ. Environmental change and out-migration: Evidence from Nepal. Popul Environ. 2010;32(2-3):109–36. doi: 10.1007/s11111-010-0119-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Espana FG. The social process of international migration. Science. 1987;237(4816):733–38. doi: 10.1126/science.237.4816.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Espinosa KE. What's driving Mexico-US migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. Am J Sociol. 1997;102(4):939–99. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin P, Dietz T. Structure, agency and environment: Toward an integrated perspective on vulnerability. Glob Environ Change. 2008;18(1):99–111. [Google Scholar]

- McLeman RA. Climate and Human Migration: Past Experiences, Future Challenges. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- McLeman R. Developments in modelling of climate change-related migration. Clim Change. 2013b;117(3):599–611. [Google Scholar]

- McLeman R, Smit B. Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Clim Change. 2006;76(1-2):31–53. doi: 10.1002/wcc.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeman RA, Hunter LM. Migration in the context of vulnerability and adaptation to climate change: insights from analogues. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 2010;1(3):450–61. doi: 10.1002/wcc.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena CF, Walsh SJ, Frizzelle BG, Xiaozheng Y, Malanson GP. Land use change on household farms in the Ecuadorian Amazon: Design and implementation of an agent-based model. Appl Geogr. 2011;31(1):210–22. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meze-Hausken E. Migration caused by climate change: how vulnerable are people in dryland areas? Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 2000;5(4):379–406. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BW, Breckheimer I, McCleary AL, Guzmán-Ramirez L, Caplow SC, et al. Using stylized agent-based models for population–environment research: a case study from the Galápagos Islands. Popul Environ. 2010;31(6):401–26. doi: 10.1007/s11111-010-0110-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey J. Rethinking the ‘debate on environmental refugees’: from ‘maximilists and minimalists’ to ‘proponents and critics’. J Polit Ecol. 2012;19:36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey J. People on the Move in a Changing Climate. New York: Springer; 2014. Environmental Change and Human Migration in Sub-Saharan Africa; pp. 81–109. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey JW. Understanding the relationship between environmental change and migration: The development of an effects framework based on the case of northern Ethiopia. Glob Environ Change. 2013;23(6):1501–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller V, Gray C, Kosec K. Heat stress increases long-term human migration in rural Pakistan. Nat Clim Change. 2014;4(3):182–85. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers N. Environmental refugees: a growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357(1420):609–13. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrotzki RJ, Riosmena F, Hunter LM. Do rainfall deficits predict US-bound migration from rural Mexico? Evidence from the Mexican census. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2013;32(1):129–58. doi: 10.1007/s11113-012-9251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan D. Geographical information science: agent-based models. Prog Hum Geogr. 2008;32(4):541–50. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Smith A. Debating environmental migration: society, nature and population displacement in climate change. J Int Dev. 2012;24(8):1058–70. [Google Scholar]

- Perz SG. Household demographic factors as life cycle determinants of land use in the Amazon. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2001;20(3):159–86. [Google Scholar]

- Reid J. Interrogating the Neoliberal Biopolitics of the Sustainable Development-Resilience Nexus. Int Polit Sociol. 2013;7(4):353–67. [Google Scholar]

- Riosmena F, Nawrotzki RJ, Hunter LM. Rainfall Trends, Variability and US Migration from Rural Mexico: Evidence from the 2010 Mexican Census. Inst. of Behav. Science, Univ. of Colo. Boulder; 2013. Work Pap. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen SJ. Cities in a World Economy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sastry N, Gregory J. The Location of Displaced New Orleans Residents in the Year After Hurricane Katrina. Demography. 2014;51(3):753–75. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0284-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffran J, Marmer E, Sow P. Migration as a contribution to resilience and innovation in climate adaptation: Social networks and co-development in Northwest Africa. Appl Geogr. 2012;33:119–27. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones I. Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis. Inst. of Dev. Stud., Brighton; 1998. Work. Pap. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Shen S, Gemenne F. Contrasted views on environmental change and migration: The case of Tuvaluan migration to New Zealand. Int Migr. 2011;49(s1):e224–42. [Google Scholar]

- Speare A. Residential satisfaction as an intervening variable in residential mobility. Demography. 1974;11(2):173–88. doi: 10.2307/2060556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporton D, Thomas DS, Morrison J. Outcomes of social and environmental change in the Kalahari of Botswana: The role of migration. J South Afr Stud. 1999;25(3):441–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stark O, Bloom DE. The new economics of labor migration. Am Econ Rev. 1985:173–78. [Google Scholar]

- Suhrke A. Environmental degradation and population flows. J Int Aff. 1994;47(2):473–96. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JE, López-Feldman A. Does migration make rural households more productive? Evidence from Mexico. J Dev Stud. 2010;46(1):68–90. [Google Scholar]

- Turner BL, Kasperson RE, Matson PA, McCarthy JJ, Corell RW, et al. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100(14):8074–79. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231335100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Geest K. North-South migration in Ghana: what role for the environment? Int Migr. 2011;49(Suppl. 1):e69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Land V, Hummel D. Vulnerability and the Role of Education in Environmentally Induced Migration in Mali and Senegal. Ecol Soc. 2013;18(4):14. [Google Scholar]

- VanWey LK, D'Antona ÁO, Brondízio ES. Household demographic change and land use/land cover change in the Brazilian Amazon. Popul Environ. 2007;28(3):163–85. [Google Scholar]

- VanWey LK, Guedes GR, D'Antona ÁO. Out-migration and land-use change in agricultural frontiers: insights from Altamira settlement project. Popul Environ. 2012;34(1):44–68. doi: 10.1007/s11111-011-0161-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R, Perz S, Caldas M, Silva LGT. Land use and land cover change in forest frontiers: The role of household life cycles. Int Reg Sci Rev. 2002;25(2):169–99. [Google Scholar]

- Warner K. Environmental change and migration: methodological considerations from ground-breaking global survey. Popul Environ. 2011;33(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Warner K, Afifi T. Where the rain falls: Evidence from 8 countries on how vulnerable households use migration to manage the risk of rainfall variability and food insecurity. Clim Dev. 2014;6(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Warner K, Hamza M, Oliver-Smith A, Renaud F, Julca A. Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Nat Hazards. 2010;55(3):689–715. [Google Scholar]

- Watts M. Nature: Culture. In: Cloke P, Johnston R, editors. Spaces of Geographical Thought: Deconstructing Human Geography's Binaries. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2005. pp. 142–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner B, Blaikie P, Cannon T, Davis I. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People's Vulnerability and Disasters. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert J. Migration as an adjustment to environmental stress. J Soc Issues. 1966;22(4):92–102. [Google Scholar]