Abstract

The aims of this study were to investigate the predictors and estimate the risk for early exit from work owing to poor personal health status of the retirees. This study analysed the longitudinal data of 2,708 workers aged more than 45 years old from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted to identify the predictors and to build a prediction model for early exit from work due to poor health. Internal validation was performed using random split, and external validation using the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Over the 8-year follow-up, 124 workers exited work early because of poor health. Significant predictors for early exit from work due to poor health included hypertension (hazard ratio [HR], 1.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–2.28), abnormal body mass index (HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.10–2.35), decreased grasping power index, and perceived health status. The prediction model designed to estimate the risk of unwanted early exit from work because of poor health status showed fair performance in both the internal and external validations. The current study revealed the specific determinants and the possibility of prediction of shortened working life due to poor health status.

Introduction

Ageing workers have increased both in number and in proportion among the working population; this has led to significant economic and public health challenges worldwide. The main reasons for this increase in ageing workers include the increasing life expectancy and decreasing birth rates1. The International Labour Organization has estimated that, by 2025, the proportions of the working population aged ≥55 years will be 21%, 32%, 30% and 17% in Asia, Europe, North America, and Latin America, respectively2.

The Republic of Korea is one of most rapidly aging countries in the world. The Korean population’s average life expectancy has increased from 72 years in 1990 to 84 years in 2014. As seen globally, the increasing age among Koreans has resulted in an increasing elderly working population. The era of ‘homo-hundred’ is almost upon us. However, an increasing older population without social or economic activity such as a job is directly associated with heavy economic and public health burdens3. Thus, several countries have established policies focused on lengthening the working life, and the determinants of early exit from work among aging workers are hence of interest4.

Early exit from work without sufficient financial preparation could bring a financial crisis to both the workers and their family5. Especially, workers who cannot continue their working life due to decreased work ability secondary to personal health problems are an important concern in the field of occupational health6. Thus, it is important to understand why workers exit work early, especially in terms of detectable and preventable public health risk factors, in an ageing society. To educate workers regarding the possibility of unwanted early exit from work due to poor health is a fundamental strategy for maintaining the working population in an ageing society.

However, until now, very little attention has been paid to health conditions linked to shortening the working life among workers. Instead, most studies in the field of early exit from work have focused on the roles of pension and economic status in making this decision. Especially, in Korea, many workers retire early because of poor health conditions7. Fortunately, pioneering existing research has recognized the critical role of the workers’ health status on a wide range of processes related to early exit from workplace, using representative data of the Korean elderly population8.

According to the above-mentioned study, both chronic disorders (hypertension and diabetes) and unhealthy behaviours (smoking and obesity) are principal determining factors of unwanted early exit from work due to health problems. Thus, the present research attempted to analyse the impact of the determinants reported in the previous study (chronic disorders and unhealthy behaviours), perceived health-related factors, and working conditions on early exit from work among Korean workers. We also assessed the probabilities of early exit from work due to the workers’ health condition, which may be helpful to ensure a longer working life among older workers. Finally, we established a prediction model of early exit from work due to the workers’ personal health status.

Results

The basic characteristics of the study participants at baseline are presented in Table 1. There were 2,708 participants in our sample, including 124 (4.6%) participants with early exit from work due to poor health (59 men and 65 women), over the 8 years of follow-up. The mean (standard error) ages at baseline were 56.54 (±0.53) and 52.34 (±0.11) years for participants who did and did not exit work early due to poor health, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants at baseline.

| Early exit from work due to poor health [n (%) or mean (±standard error)] | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| No. of participants | 2,584 (95.42) | 124 (4.58) | |

| Age (years) | 52.34 (±0.11) | 56.54 (±0.53) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | <0.0001 | ||

| Men | 1,779 (96.79) | 59 (3.21) | |

| Women | 805 (92.53) | 65 (7.47) | |

| Marital status | 0.1905 | ||

| Married | 2,324 (95.60) | 107 (4.40) | |

| Divorced, separated, or never | 260 (93.86) | 17 (6.14) | |

| Education | <0.0001 | ||

| Middle school | 994 (93.16) | 73 (6.84) | |

| High school | 1,079 (96.77) | 36 (3.23) | |

| College or university | 511 (97.15) | 15 (2.85) | |

| Household income ($) | 0.0007 | ||

| <20,000 | 992 (93.67) | 67 (6.33) | |

| <30,000 | 498 (95.95) | 21 (4.05) | |

| <40,000 | 479 (96.57) | 17 (3.43) | |

| ≥40,000 | 615 (97.00) | 19 (3.00) | |

| Type of work | 0.1409 | ||

| Paid worker | 1,452 (94.90) | 78 (5.10) | |

| Self-employed | 1,132 (96.10) | 46 (3.90) | |

| Occupational classification | 0.1849 | ||

| Higher-skilled white collar | 291 (96.04) | 12 (3.96) | |

| Lower-skilled white collar | 413 (96.95) | 13 (3.05) | |

| Pink collar | 595 (94.59) | 34 (5.41) | |

| Green collar | 173 (95.58) | 8 (4.42) | |

| Skilled blue-collar | 606 (96.04) | 25 (3.96) | |

| Unskilled blue-collar | 506 (94.05) | 32 (5.95) | |

| Size of enterprise | 0.1863 | ||

| <30 or one-man company | 1,728 (95.05) | 90 (4.95) | |

| >30 or hired employee | 856 (96.18) | 34 (3.82) | |

| Time of work | 0.1688 | ||

| Part-time | 240 (97.17) | 7 (2.83) | |

| Full-time | 2,344 (95.25) | 117 (4.75) | |

| Smoking | 0.0221 | ||

| Never or past | 1,747 (94.79) | 96 (5.21) | |

| Current | 837 (96.76) | 28 (3.24) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.9530 | ||

| Never or social | 2,183 (95.41) | 105 (4.59) | |

| Heavy | 401 (95.48) | 19 (4.52) | |

| Exercise status | 0.0425 | ||

| None | 1,535 (94.75) | 85 (5.25) | |

| Regular | 1,049 (96.42) | 39 (3.58) | |

| Hypertension | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 2,215 (96.26) | 86 (3.74) | |

| Yes | 369 (90.66) | 240 (9.34) | |

| Diabetes | 0.0087 | ||

| No | 2,359 (95.72) | 107 (4.28) | |

| Yes | 189 (91.75) | 17 (8.25) | |

| Obesity or underweight | 0.0034 | ||

| No | 1,912 (96.13) | 77 (3.87) | |

| Yes | 672 (93.46) | 47 (6.54) | |

| Depression | 0.0447 | ||

| No | 2,158 (95.78) | 95 (4.22) | |

| Yes | 426 (93.63) | 29 (6.37) | |

| Grasping power index | 31.66 (±0.16) | 26.55 (±0.66) | <0.0001 |

| Perception factor scores | |||

| Health status | 6.68 (±0.04) | 5.67 (±0.22) | <0.0001 |

| Economic status | 5.42 (±0.04) | 4.96 (±0.21) | 0.0319 |

| Quality of life | 6.68 (±0.04) | 6.44 (±0.15) | 0.1174 |

| Working life expectancy | 8.10 (±0.05) | 6.83 (±0.29) | <0.0001 |

In terms of socioeconomic status, the highest proportions of early exit from work due to poor health were reported in those with an education status of less than middle school graduation (6.84%) and among participants with the lowest household income level (6.33%), with statistical significance (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0007, respectively).

Regarding the occupational characteristics, regular paid workers showed a higher proportion of early exit from work due to poor health than those who were self-employed. Especially, unskilled blue-collar workers had the highest prevalence of early exit from work due to poor health (5.95%), but there was no statistical significance. Moreover, non-significant tendencies of higher prevalence of early exit from work due to poor health were noted in small-size enterprises (<30 workers and one-man companies) and full-time workers.

In terms of health status, participants who did not exercise regularly showed a higher prevalence of early exit from work due to poor health than their counterparts. Furthermore, participants with hypertension, diabetes, abnormal BMI, and lower grasping power index demonstrated significantly higher prevalence rates of unwanted early exit from work.

For the perception status, the participants with early exit from work due to poor health showed significant lower mean scores in the health, economic, and working life expectancy statuses.

Table 2 shows the risks for early exit from work due to poor health according to several covariates. Significantly decreased risks of early exit from work due to poor health were found to correlate with increased education (HR, 0.49–0.44) and household income levels (HR, 0.65, 0.55, and 0.49, respectively) in the univariate analyses.

Table 2.

Results from the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of early exit from work due to poor health.

| Cases (n) | Person-years | Early exit from work due to poor health, Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Fully adjusted | |||

| Age (years) | — | — | 1.14 (1.11–1.18) | 1.15 (1.10–1.19) |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 59 | 295 | reference | reference |

| Women | 65 | 244 | 2.49 (1.75–3.54) | 1.63 (0.81–3.26) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 107 | 467 | reference | reference |

| Divorced, separated, or never | 17 | 72 | 1.58 (0.95–2.64) | 1.23 (0.71–2.12) |

| Education (graduation) | ||||

| Middle school | 73 | 311 | reference | reference |

| High school | 36 | 158 | 0.49 (0.31–0.68) | 1.11 (0.70–1.77) |

| College or university | 15 | 70 | 0.44 (0.25–0.78) | 1.10 (0.53–2.33) |

| p value for linear trend | 0.0001 | 0.7157 | ||

| Household income ($) | ||||

| <20,000 | 67 | 298 | reference | reference |

| <30,000 | 21 | 74 | 0.65 (0.40–1.06) | 1.01 (0.61–1.70) |

| <40,000 | 17 | 81 | 0.55 (0.33–0.94) | 0.99 (0.56–1.75) |

| ≥40,000 | 19 | 86 | 0.49 (0.29–0.81) | 0.78 (0.43–1.44) |

| p value for linear trend | 0.0016 | 0.5242 | ||

| Type of work | ||||

| Paid worker | 78 | 332 | reference | reference |

| Self-employed | 46 | 207 | 0.59 (0.38–0.90) | 0.70 (0.49–1.01) |

| Occupational classification | ||||

| Higher-skilled white collar | 12 | 60 | reference | reference |

| Lower-skilled white collar | 13 | 47 | 0.70 (0.32–1.54) | 0.41 (0.17–1.00) |

| Pink collar | 34 | 135 | 1.22 (0.63–2.36) | 0.55 (0.24–1.30) |

| Green collar | 8 | 39 | 0.86 (0.35–2.10) | 0.28 (0.09–0.83) |

| Skilled blue-collar | 25 | 119 | 0.90 (0.45–1.79) | 0.57 (0.25–1.33) |

| Unskilled blue-collar | 32 | 139 | 1.39 (0.72–2.71) | 0.42 (0.18–0.99) |

| Size of enterprise | ||||

| ≤30 or one-man company | 90 | 390 | reference | reference |

| >30 or hired employer | 34 | 149 | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) | 1.06 (0.69–1.64) |

| Time of work | ||||

| Part-time | 7 | 23 | reference | reference |

| Full-time | 117 | 516 | 2.59 (1.17–5.72) | 1.47 (0.69–3.15) |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never or past | 96 | 404 | reference | reference |

| Current | 28 | 135 | 0.61 (0.40–0.94) | 1.08 (0.66–1.79) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Never or social | 105 | 468 | reference | reference |

| Heavy | 19 | 71 | 0.98 (0.60–1.59) | 1.18 (0.69–2.00) |

| Exercise status | ||||

| None | 39 | 180 | reference | reference |

| Regular | 85 | 359 | 0.67 (0.46–0.98) | 0.70 (0.47–1.06) |

| Hypertension | ||||

| No | 86 | 381 | reference | reference |

| Yes | 38 | 158 | 2.60 (1.78–3.82) | 1.52 (1.01–2.28) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 107 | 454 | reference | reference |

| Yes | 17 | 85 | 1.87 (1.12–3.12) | 1.31 (0.77–2.23) |

| Obesity or underweight | ||||

| No | 77 | 330 | reference | reference |

| Yes | 47 | 209 | 1.69 (1.18–2.43) | 1.60 (1.10–2.35) |

| Depression | ||||

| No | 95 | 428 | reference | reference |

| Yes | 29 | 111 | 1.51 (1.00–2.29) | 0.94 (0.60–1.49) |

| Grasping power index | — | — | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | 0.95 (0.91–0.98) |

| Perception factor scores | ||||

| Health status | — | — | 0.81 (0.75–0.87) | 0.86 (0.78–0.95) |

| Economic status | — | — | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) |

| Quality of life | — | — | 0.93 (0.84–1.02) | 1.09 (0.96–1.24) |

| Working life expectancy | — | — | 0.85 (0.80–0.89) | 0.94 (0.88–1.00) |

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

The associations of older age, hypertension, and abnormal BMI with increased risk for early exit from work due to poor health remained in the multivariate analysis, with HRs (95% CIs) of 1.15 (1.10–1.19), 1.52 (1.01–2.28), and 1.60 (1.10–2.35), respectively. Moreover, increased grasping power index and perceived health status score were significantly associated with reduced risks of early exit from work due to poor health.

On the other hand, no significant association was observed between early exit from work due to poor health and marital status, enterprise size, alcohol consumption, or perceived quality of life in either the univariate or multivariate analysis.

To understand the key factors of early exit from work due to poor health, a prediction model was developed using the results from the Cox regression model. By stepwise elimination of the Cox regression model, literature review, and discussion with occupational and public health professions, finally, nine covariates were selected as the main features related to early exit from work due to poor health. These included age and sex among the basic characteristics; smoking and alcohol consumption among health behaviours; hypertension, diabetes, and abnormal BMI among disease statuses; and the perceived health and working life expectancy scores among the perception factors.

In detail, age, hypertension, abnormal BMI, and self-rated health status were selected by statistical significance in the Cox regression model and based on a previous study8,9. Sex was selected as an important covariate due to the fact that sex-differentiation can influence not only early exit from work decisions but also the later-life course10. Diabetes and both health behaviours (smoking and alcohol consumption) were added into the prediction model despite not showing statistical significance. In many countries, regular medical health examinations are conducted for working individuals to identify chronic disorders (hypertension, obesity, and diabetes) and poor health behaviours (smoking and alcohol). After discussion with occupational and public health professions, the final prediction model therefore included three non-significant medical examination-related factors: diabetes, smoking, and alcohol consumption level.

The HR (95% CI) of the working life expectancy score did not show obvious statistical significance; however, it indicated a tendency of a close link with early exit from work (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.88–1.00 from the fully adjusted model). Furthermore, a previous study has indicated that working life expectancy scores can critically impact on later life and health11.

The grasping power index and occupational classification could not be parted in the prediction model, despite showing significant relationships with early exit from work. The grasping power index for general health is not yet established, although this score is frequently used to assess neurological motor function. Herein, we only could reveal the possibility of the grasping power index to be used as a later life-related factor. Moreover, green- and unskilled blue-collar workers showed significant vulnerability of early exit from work. However, their significant occupational classification was removed from the final prediction model due to the heterogeneity within each category such as in age and income.

HRs with exponentiated regression coefficients, obtained from the Cox regression model in Table 2, were used to build the risk score for the 8-year follow-up risk for non-voluntary early exit from work due to poor health. The early exit from work due to poor health risk score was constructed using beta estimates from the multivariate Cox regression analysis and the prevalence or mean of each predictive factor.

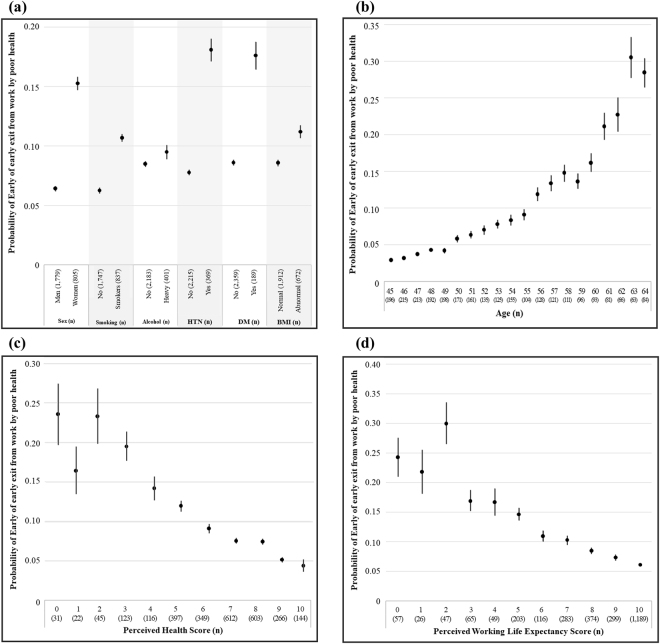

Figure 1 demonstrates the mean and 95% CIs of the probability of early exit from work due to poor health estimated from the Cox regression model according to each predictive factor. Female workers, smokers, heavy alcohol consumption, and chronic disorders (hypertension, diabetes, and abnormal BMI) associated with high probabilities of early exit from work due to poor health. There were also the probabilities of early exit from work due to poor health according to increasing age, decreasing perceived health score, and the working life expectancy score.

Figure 1.

Mean probabilities of early exit from work by poor health according to (a) sex, health behaviours, and chronic disorders; (b) age; (c) perceived health score; and (d) perceived working life expectancy score. HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; BMI, body mass index.

Performance of the Prediction Model for Early Exit from Work due to Poor Health

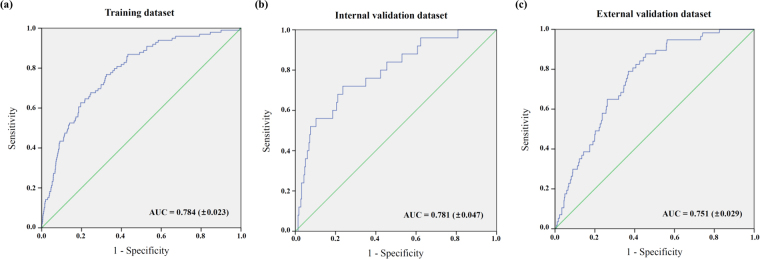

To evaluate the performance of the prediction model for early exit from work due to poor health, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis with area under the curve (AUC) calculations were conducted in three different datasets, as summarized in Fig. 2. These included a (a) training dataset, (b) internal validation dataset from random split, and (c) external validation from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Our prediction model based on the Cox regression models showed fair AUCs of 0.784 (±0.023) in the training data set, 0.781 (±0.047) in the internal validation dataset, and 0.751 (±0.029) in the external validation dataset.

Figure 2.

Areas under the curve (AUC) for early exit from work due to poor health. (a) Training, (b) internal validation, and (c) external validation datasets.

The predictive ability of the model was described by its sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy in each dataset, as summarized in Table 3. The internal validation dataset showed a sensitivity of 72.0%, specificity of 66.2%, positive predictive value of 9.3%, negative predictive value of 97.9%, and accuracy of 66.4%. The corresponding values in the external validation dataset were 94.7%, 63.0%, 6.4%, 99.7%, and 63.8%, respectively.

Table 3.

Predictive ability of the model for early exit from work due to poor health.

| Internal validation | External validation | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 542 | 2,204 |

| Sensitivity | 72.0% | 94.7% |

| Specificity | 66.2% | 63.0% |

| Positive predictive value | 9.3% | 6.4% |

| Negative predictive value | 97.9% | 99.7% |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 2.12 | 2.56 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.42 | 0.08 |

| Accuracy | 66.4% | 63.8% |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to create a prediction model of early exit from work due to poor health using various risk factors, including basic characteristics, health status, and perception factors. Specifically, we found that poor health status (hypertension and abnormal BMI) and low perceived health status were significantly associated with early exit from work due to poor health.

These results regarding the specific predictors of early exit from work due to poor health may help explain the findings of previous investigations. For example, chronic illness (hypertension or obesity) was reported as a risk factor of early exit from work due to poor health in a previous study using data from the Studies on Health and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)12. However, the current investigation further indicated that chronic disorders were significantly related with early exit from work due to poor health. Furthermore, other previous studies have reported limited associations between perceived health status and early exit from work13. The results from the current analysis suggest that perceived health status is significantly linked to early exit from work due to poor health.

Over 75% of ageing workers have been reported to choose to continue working even if they develop a significantly reduced work ability14. Unfortunately, the ageing process, which is often accompanied by disorders and inappropriate health behaviours, places burdens on the workers’ health that may cut their working life short15,16. Poor health conditions can lead to poor work performance, and both are important factors related to early exits from working life17,18. Indeed, to encourage a working life without poor health conditions, the risk for early exit from work due to poor health needs to be assessed.

In the present study, to identify the key obstacles to a sustainable working life, a statistical approach based on the current data and a literature review was used. As a result, this study identified nine factors as determinants of unwanted early exit from work due to poor health, including age, sex, health behaviours (smoking and alcohol consumption), chronic disorders (hypertension, diabetes, and abnormal BMI), and perception factors (health score and working life expectancy score).

Age is a fundamental component of researches in the elderly population, and plays a key role in early exit from work9. In the current analysis, the risk of early exit from work due to poor health showed a significant positive association with increasing age. The biological process of ageing is directly linked to worsened general health conditions, including work ability19. It is hard to stop the effects of ageing in humans; however, understanding the effects of age is a cornerstone in the evaluation of sustainable working life.

A much-debated question is whether health behaviours are related with early exit from work. Many studies, including the current one, were unable to demonstrate significant relationships, while others reported inverse relationships between smoking or alcohol consumption status and early exit from work8,20. However, one study focusing on early exit from work due to disability reported that smoking and alcohol were obvious risk factors21. In general, smoking and heavy consumption of alcohol are known risk factors for reduced workability and increased disability related to the workplace22,23. Furthermore, the workers’ smoking and alcohol consumption habits are some of the first questions during the regular medical check-ups for workers in Korea. Thus, this study considered cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption as predictive factors for early exit from work due to poor health.

According to previous researches and the present study, chronic disorders, including hypertension, diabetes, and abnormal BMI, can be strong factors associated with shortened working life24–26. In public health policies, these conditions are given priority, and, in clinical practice, evaluations of blood pressure, blood glucose, and anthropometry are fundamental in regular workers’ medical examinations.

The close linkage between perception and decision-making represents a well-established theory to explain human behaviour. Perception is a serial process of organizing and interpreting stimuli from the environment in order to give it meaning. Based on these interpretations and analyses of the situation, combined with a rational analysis, individuals will make a decision27,28. In occupational health, subjective perception is an important factor to understand workers’ health and behaviours. For example, workers who report higher perceived work stress and physical workload have been reported to be more likely to have neuromuscular disorders than those with lower scores29,30. Thus, we hypothesize that, in cases of early exit from work due to poor health cases, positive perceptions of health and sustainability of work life were unlikely to remain.

In the current study, decreased perceived health condition significantly associated with an increased risk for early exit from work due to poor health. Previous studies have also reported that perceived health status could be used as a predictor of unwanted early exit from work related to poor health18,31,32. Workers’ self-perceived health status deteriorates with age, and chronic diseases are common in older populations33. Moreover, participants in surveys related to old age are frequently asked about their subjective health status. Thus, using perceived health status is associated with several advantages for predicting the risk of early exit from work due to poor health.

There are currently limited published data on the relationship between perceived working life expectancy and early exit from work. However, the current study and a previous study by our group showed the possibility of using perceived working life expectancy as a predictor of early exit from work11. Using the exact working life expectancy score, similar to in the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA) and ELSA, a previous study reported that self-rated workability was closely related with unwanted exit from working life34. Hence, these two perception factors could potentially be applied to build a prediction model.

The current study suggested a novel prediction model for early exit from work due to poor health in older workers by considering nine core factors, including basic characteristics, health behaviours, chronic disorders, and perception factors. The performance of the prediction model was fair, and it was not attenuated even after external validation using data from the ELSA. More information regarding ageing workers at risk of early exit from work secondary to their health behaviours or chronic disorders may help increase the awareness of the importance of good health behaviours such as quitting smoking, reducing consumption of alcohol, and losing weight. It can thus be suggested that the prediction model from this study can be used to evaluate the risk of, or to identify vulnerable workers for, early exit from work due to poor health.

In many countries, occupational health is assessed through regular medical examinations (annually for labour workers and biennially in office workers) to prevent poor workers’ health. Nonetheless, many workers in this study could not remain in their workplace due to poor personal health conditions. This is also a main issue for lengthening working life, as poor health is, at least partially, preventable with appropriate knowledge and health management among elderly workers. Thus, occupational health professionals can also use our prediction model for early exit from work due to poor health to improve the workers’ health.

In general, it seems that, for understanding the process of shortened working life, determinants of early exit from work due to poor health should be considered. The current study has important implications on occupational health in that it revealed the possibility of prediction of unwanted early exit from work due to poor health. Predictability allows for the possibility of prevention. Taken together, our findings suggest a role of our prediction model as a preventive strategy of unwanted early exit from the workplace by poor health.

Nevertheless, despite these implications of our study, the results from the current analysis must be interpreted with caution because of the nature of the data. The survey data from the KLoSA were based on self-administered questionnaires. Surveys based on questionnaires are likely to have various errors such as specification, frame, nonresponse, measurement, and processing errors. Especially, self-rated perception-related questionnaires by retirees with poor health might also have bias. While the KLoSA applied computer-assisted interviews by trained researchers to reduce these errors, these limitations are not specific to research based on the KLoSA, and have been reported for surveys of the elderly population in various countries worldwide, including for the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), ELSA, and SHARE35,36. More subjective measurements and reports are needed to ensure the reliability and validity, as well as the practical applicability, of the KLoSA questionnaires. Furthermore, the small positive predictive value of our prediction model does not allow for the results from the current analysis to be immediately applied to workers. However, the prediction model of the current study showed moderate to good validity in terms of the sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value (Table 3), and good performance in terms of the AUCs (Fig. 2). Hence, we consider that this research may serve as a cornerstone for future studies about the prediction and prevention of unwanted early exit from workplace due to health problems. Finally, we researched exit from work focused on middle and older aged workers. However, the lack of jobs or forced retirement are same issues among younger adults who have poor health conditions too in many countries. More broad generation, research is also needed to understand early exit from work due to poor health process.

In conclusion, the present large-scale longitudinal study focusing on the older working population (including regular paid and self-employed workers) revealed several specific determinants of shortened work life because of poor health among workers. A prediction model from our investigation was proposed to evaluate the risk of early exit from work due to poor health. The performance of this prediction model was fair and was not attenuated even after external validation. Taken together, our results suggest that it is important to understand the determinants of early exit from work due to poor health, and estimations of the probabilities of unwanted early exit from work due to poor health condition should be considered a key factor in extending the working life in ageing workers.

Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

The current study used data from the first to fifth (2006–2014) waves of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA), conducted by the Korea Labour Institute and the Korea Employment Institute Information Service. The KLoSA was conducted to obtain an overview of what it means to grow older and to help us understand what accounts for the variety of patterns that are seen. The KLoSA is a nationally representative panel survey of Korean citizens aged over 45 years. The panel survey, which has been conducted every 2 years since 2006, was built to provide a national resource for data on the changing age-related socioeconomic and health circumstances. Its multidisciplinary approach is focused on broad topics, including socioeconomics, health status, and relationships. The KLoSA was started with surveys and interviews of 10,254 randomly selected adults residing in one of 15 city-size administrative areas in the Republic of Korea in 2006. The KLoSA collects information about household and individual demographics; medical, physical, and psychosocial health; work and pensions; income and assets; housing; cognitive function; social participation and networks; expectations; and objective estimations, including physical and performance measures. The participants were interviewed using computer-assisted personal interviews, where the professional interviewers instructed the respondents to read the questions on a computer and input their answers directly.

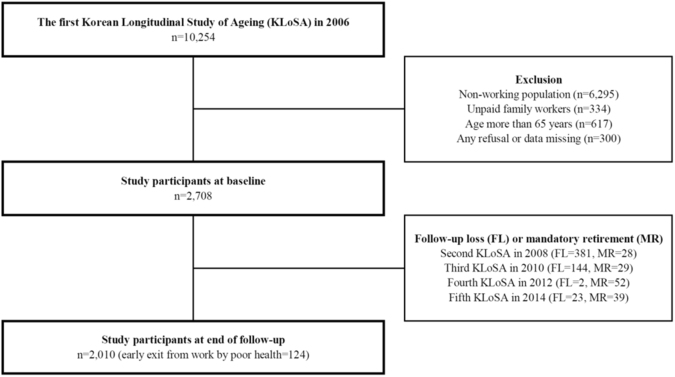

In this study, a longitudinal approach was adopted to develop an 8-year early exit from work prediction model; the baseline period used for this study was the first phase of the KLoSA (n = 10,254) conducted in 2006. In order to investigate the predictors of early exit from work, the non-working population (n = 6,295) and unpaid family workers (n = 334) were excluded from the study. Workers aged >65 years (n = 617) at baseline were also excluded according to the definition of early exit from work. Moreover, 300 participants who refused to participate or those with missing relevant covariates data were also excluded from the study. Finally, 2,708 workers were included in the current study at baseline (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the study participants.

Each KLoSA participant was identified using a randomly selected number to ensure their anonymity. The interviewers provided information about the research objectives and potential risks and benefits to all survey respondents, who provided informed consent before they answered any questions. All respondents also agreed to participate in further scientific research. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Graduate School of Public Health, Korea (No. 2-1040939-AB-N-01-2016-167). This study followed the STROBE (Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology) reporting guidelines for observational cohort studies.

Early Exit from Work

Early exit from work can be defined as retirement before normal pension age. In Korea, the beginning ages of normal pension age are separated according to the year of birth (~1952, 1952–1962, 1963–1964, and 1965~). Most people born after 1965 will retire at 65 years. Workers who retire before this age are defined as early retirement workers. Early exit from work may also be defined as retirees who retire despite the ability and will to work due to various reasons. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports in 2017 (http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/oecd-pensions-at-a-glance_19991363;jsessionid=1ckwr6b4gmbr5.x-oecd-live-02), the average effective age of labour market exit was 65.1 years for men and 63.6 years for women across OECD countries. In Korea, the average effective age of labour market exit was the highest among the OECD countries (72.0 years for men and 72.2 years for women). Considering the various definitions of early exit from work and social circumstances in Korea, in this study, we defined early exit from work using a less strict standard, as retirement before 65 years.

In order to identify early exit from work due to poor health, newly recognized retirees during the follow-up periods were asked regarding the reason for retirement in each wave. The possible answers were categorized as follows: (1) sufficient income, (2) sufficient income of their spouse, (3) being weary of work, (4) wanting to have more leisure time, (5) wanting to spend time volunteering or on a hobby, (6) poor personal health status, (7) poor health of their spouse, (8) poor health of family members, (9) housework or childcare, (10) unable to find other work, (11) regular retirement, and (12) any other reasons. Participants who answered with 11 and 12 were excluded from the study, as these cases were considered mandatory retirement.

The retired participants who answered ‘(6) due to poor personal health status’ were defined as ‘early exit from work due to poor health.’

Socioeconomic Variables

The current study used age, sex, marital status, education, and household income as socioeconomic variables. Marital status was divided into two categories (married vs. divorced, separated, or never). Educational level was divided into the following three categories: less than middle school graduation, high school graduation, and above. Household income level was categorized as follows: <$20,000, <$30,000, <$40,000, and ≥$40,000.

Occupational Characteristics

Occupational characteristics included the type of work, occupational classification, size of enterprise, and time of work. The occupational classifications were regrouped into six out of the 10 major categories (suggested by the International Standard Classifications of Occupations, as per the social and cultural circumstances of the Republic of Korea as well as the skill and duty levels reported in a previous study37), as follows: higher-skilled white-collar workers (legislators, senior officials, managers, and professionals), lower-skilled white-collar workers (technicians and associated professionals), pink-collar workers (clerk, sales, and customer service workers), green-collar workers (agriculture, fishery, and forestry), skilled blue-collar workers (craft, plant and machine operators, and assemblers), and unskilled blue-collar workers (elementary workers). The size of the enterprise was divided into two categories considering the type of work (regular paid workers and self-employed), as follows: self-employed one-man companies and companies with <30 workers among paid workers were grouped into same category, while all other enterprises were grouped together.

Health Status

Smoking, alcohol consumption, and exercise level were considered as health behaviour-related covariates. Smoking history was categorized as never/past smokers or current smokers. Heavy alcohol consumption was defined as alcohol consumption of at least 15 standard drinks per week in men and at least 8 standard drinks per week in women. Regular exercise was defined as exercising more than once a week, as determined using the questionnaire.

The KLoSA included information about the participants’ medical history. Diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes, depression, and measured abnormal BMI (≥25 kg/m2, obesity; <18.5 kg/m2, underweight) were included as relevant disease histories of the participants, as chronic diseases can lead to work disability in the older population33,38.

The grasping power index reflects age-related health conditions, similar to the gait speed and balancing on one-foot tests. For each hand, the mean of three trials of grip strength was calculated while considering the participants’ conditions for gripping and hand dominance39.

Perception Factors

The KLoSA included questionnaires about the self-rated expectations or satisfactions of the participants. The current study used three satisfaction factors (health, economic, and quality of life) and one expectation factor (working life expectancy). Self-rated satisfaction levels are considered key aspects related to unwanted early exit from work among elderly workers40,41. The participants were asked about their health/economic/quality of life satisfaction as follows: “How satisfied are you with your health/economic/quality of life status?” Working life expectancy has also been reported as an important factor related to the ageing population11. Questions about the working life expectancy were asked to the participants according to their age group, using the following statements: “I can keep working in this job until 55 years old” to those <50 years of age, “I can keep working in this job until 60 years old” to those aged between 50–54 years, and “I can keep working in this job for 5 more years” to those aged >55 years. The possible answers to these statements were provided using a visual analogue scale (0–10 points). A score of 0 signified “never” or “it will never happen to me”, while a score of 10 signified “always” or “it will definitely happen to me.”

Statistical Analysis

The frequency of unwanted early exit from work due to poor health was calculated for each data category, and the chi-squared test or t-test was used to evaluate the association between each variable and early exit from work. The survival time was defined as the interval between the survey date of the first wave and the date of early exit from work due to poor health. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by Cox regression models to evaluate the risks for early exit from work due to poor health.

A Cox regression model was also used to construct a prediction model for the 8-year probability of early exit from work due to poor health as a means to identify vulnerable workers and to provide information related to unexpected early exit from work. A functional formula for probabilities of early exit from work due to poor health according can see in Supplementary Table 1.

For the feature selection, backward stepwise elimination was conducted along with a literature review and expert discussion.

For internal validation, the dataset was divided randomly into training (80%, n = 2,166) and test sets (20%, n = 542), with conservation of the prevalence of early exit from work due to poor health. The KLoSA was developed as part of a research network with the ‘Health and Retirement Study (HRS)’ in the US, ‘Studies on Health and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)’ in the EU, and ‘English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA)’ in the UK. These studies were designed to share key areas of research, reflect cultural circumstances, and use understandable measurements, and are international comparable studies to the KLoSA42. Thus, for external validation, data from the ELSA were used. The ELSA is a panel study of a representative cohort of the elderly population living in England43. It was designed as a sister study to the HRS and contains multidisciplinary data, with a similar structure to the KLoSA. The panel was initially held in 2002, and the participants (>10,000) have been followed-up every 2 years. We used data from 2006 to 2014 of the ELSA to match the follow-up periods of the current analysis data from the KLoSA. A total of 2,204 participants were selected under the same conditions as for current analysis dataset from the KLoSA.

Area under the curve (AUC) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were conducted to evaluate the performance of the prediction model for early exit from work due to poor health. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Two-tailed p values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

All authors would like to thank the participants of the KWCS for the opportunity for performing this research.

Author Contributions

W.L. conceived the idea for the study, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and revised the manuscript. J.-H.Y. and J.-U.W. contributed to develop the study design, conducted the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. J-W.K. and S.-J.C. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results. J.R. contributed to draft and revise the manuscript. J.-U.W. is the corresponding author of this work and, as such, takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23523-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shultz, K. S. and Adams, G. A. Aging and work in the 21st century (Psychology Press, 2012).

- 2.Ilmarinen JE. Aging workers. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2001;58:546–546. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.8.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dwyer DS, Mitchell OS. Health problems as determinants of retirement: Are self-rated measures endogenous? Journal of health economics. 1999;18:173–193. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(98)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berecki-Gisolf J, Clay FJ, Collie A, McClure RJ. The impact of aging on work disability and return to work: insights from workers’ compensation claim records. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2012;54:318–327. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31823fdf9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alessie, R. J., Van Rooij, M. & Lusardi, A. Financial literacy, retirement preparation and pension expectations in the Netherlands (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2011).

- 6.Pit SW, Shrestha R, Schofield D, Passey M. Health problems and retirement due to ill-health among Australian retirees aged 45–64 years. Health Policy. 2010;94:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S, Cho S-I, Jang S-N. Health conditions sensitive to retirement and job loss among Korean middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2012;45:188–195. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang M-Y, Yoon C-g, Yoon J-H. Influence of illness and unhealthy behavior on health-related early retirement in Korea: Results from a longitudinal study in Korea. Journal of occupational health. 2015;57:28–38. doi: 10.1539/joh.14-0117-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoeni RF, Ofstedal MB. Key themes in research on the demography of aging. Demography. 2010;47:S5–S15. doi: 10.1353/dem.2010.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noone J, Alpass F, Stephens C. Do men and women differ in their retirement planning? Testing a theoretical model of gendered pathways to retirement preparation. Research on Aging. 2010;32:715–738. doi: 10.1177/0164027510383531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee W, Hong K, Lim S-S, Yoon J-H. Does pain deteriorate working life expectancy in aging workers? Journal of Occupational Health. 2016;58:582–592. doi: 10.1539/joh.16-0024-OA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerke, O. and Lauridsen, J. T. Determinants of early retirement in Denmark. An empirical investigation using SHARE data. Discussion papers on business and economics (2013).

- 13.Mein G, et al. Predictors of early retirement in British civil servants. Age and ageing. 2000;29:529–536. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoddard, S., Jans, L., Ripple, J. M. & Kraus, L. Chartbook on Work and Disability in the United States, 1998 (1998).

- 15.Von Bonsdorff, M. E., Huuhtanen, P., Tuomi, K. & Seitsamo, J. Predictors of employees’ early retirement intentions: an 11-year longitudinal study. Occupational Medicine kqp126 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Koolhaas W, et al. In-depth study of the workers’ perspectives to enhance sustainable working life: comparison between workers with and without a chronic health condition. Journal of occupational rehabilitation. 2013;23:170–179. doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegrist J, Wahrendorf M, Von dem Knesebeck O, Jürges H, Börsch-Supan A. Quality of work, well-being, and intended early retirement of older employees—baseline results from the SHARE Study. The European Journal of Public Health. 2007;17:62–68. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karpansalo, M., Manninen, P., Kauhanen, J., Lakka, T. A. & Salonen, J. T. Perceived health as a predictor of early retirement. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health 287–292 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Cho IH, Park KS, Lim CJ. An empirical comparative study on biological age estimation algorithms with an application of Work Ability Index (WAI) Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2010;131:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lund T, Iversen L, Poulsen KB. Work environment factors, health, lifestyle and marital status as predictors of job change and early retirement in physically heavy occupations. American journal of industrial medicine. 2001;40:161–169. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korhonen T, Smeds E, Silventoinen K, Heikkilä K, Kaprio J. Cigarette smoking and alcohol use as predictors of disability retirement: A population-based cohort study. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015;155:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Böckerman P, Hyytinen A, Maczulskij T. Devil in disguise: Does drinking lead to a disability pension? Preventive medicine. 2016;86:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bengtsson, T. and Nilsson, A. Smoking Behaviour and Early Retirement Due to Chronic Disability (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kang YJ, Kang M-Y. Chronic Diseases, Health Behaviors, and Demographic Characteristics as Predictors of Ill Health Retirement: Findings from the Korea Health Panel Survey (2008–2012) PloS one. 2016;11:e0166921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomes MB, Negrato CA. Retirement due to disabilities in patients with type 1 diabetes a nationwide multicenter survey in Brazil. BMC public health. 2015;15:486. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1812-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ervasti J, et al. Health-and work-related predictors of work disability among employees with a cardiometabolic disease—A cohort study. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2016;82:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravlin EC, Meglino BM. Effect of values on perception and decision making: A study of alternative work values measures. Journal of Applied psychology. 1987;72:666–673. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.72.4.666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swets JA, Tanner WP, Jr, Birdsall TG. Decision processes in perception. Psychological review. 1961;68:301. doi: 10.1037/h0040547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ando S, et al. Associations of self estimated workloads with musculoskeletal symptoms among hospital nurses. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2000;57:211–211. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burdorf, A. and van der Beek, A. J. In musculoskeletal epidemiology are we asking the unanswerable in questionnaires on physical load? Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health 81–83 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Schuring M, Robroek SJ, Lingsma HF, Burdorf A. Educational differences in trajectories of self-rated health before, during, and after entering or leaving paid employment in the European workforce. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health. 2015;41:441–450. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Wind A, et al. Health, job characteristics, skills, and social and financial factors in relation to early retirement–results from a longitudinal study in the Netherlands. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health. 2014;40:186–194. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler RC, Greenberg PE, Mickelson KD, Meneades LM, Wang PS. The effects of chronic medical conditions on work loss and work cutback. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2001;43:218–225. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sell L. Predicting long-term sickness absence and early retirement pension from self-reported work ability. International archives of occupational and environmental health. 2009;82:1133–1138. doi: 10.1007/s00420-009-0417-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savva GM, Maty SC, Setti A, Feeney J. Cognitive and physical health of the older populations of England, the United States, and Ireland: international comparability of the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61:S291–S298. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson WK, Cronin H, Kenny RA, Setti A. Validation of the self-reported hearing questions in the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing against the Whispered VoiceTest. BMC research notes. 2014;7:361. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee W, et al. Metabolic outcomes of workers according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations in Korea. American journal of industrial medicine. 2016;59:685–694. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van den Berg T, Schuring M, Avendano M, Mackenbach J, Burdorf A. The impact of ill health on exit from paid employment in Europe among older workers. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2010;67:845–852. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.051730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jang, S.-N. Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA): Overview of Research Design and Contents. Encyclopedia of Geropsychology 1–9 (2015).

- 40.Westerlund H, et al. Self-rated health before and after retirement in France (GAZEL): a cohort study. The Lancet. 2009;374:1889–1896. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lund T, Borg V. Work environment and self-rated health as predictors of remaining in work 5 years later among Danish employees 35-59 years of age. Experimental aging research. 1999;25:429–434. doi: 10.1080/036107399243904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boo, K.-C. and Chang, J.-Y. Korean longitudinal study of ageing: research design for international comparative studies. Survey Research7 (2006).

- 43.Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J. Cohort profile: the English longitudinal study of ageing. International journal of epidemiology. 2012;42:1640–1648. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.