Abstract

Objective

To report on medical schools in fragile states, countries with severe development challenges, and the impact on the workforce for health care delivery.

Data Sources

2007 and 2012 World Bank Harmonized List of Fragile Situations; 1998–2012 WHO Global Health Observatory; 2014 World Directory of Medical Schools.

Data Extraction

Fragile classification established from 2007 and 2012 World Bank status. Population, gross national income, health expenditure, and life expectancy were 2007 figures. Physician density was most recently available from WHO Global Health Observatory (1998–2012), with number of medical schools from 2014 World Directory of Medical Schools.

Study Design

Regression analyses assessed impact of fragile state status in 2012 on the number of medical schools in 2014.

Principal Findings

Fragile states were 1.76 (95 percent CI 1.07–2.45) to 2.37 (95 percent CI 1.44–3.30) times more likely to have fewer than two medical schools than nonfragile states.

Conclusions

Fragile states lack the infrastructure to train sufficient numbers of medical professionals to meet their population health needs.

Keywords: Delivery of care, workforce issues, disease outbreaks, domestic and global health

Fragile states are countries with severe development challenges due to weak institutional capacity, unstable governance, and political volatility (World Bank 2015). Disease outbreaks and complex humanitarian emergencies occur disproportionately in fragile states. The recent Ebola virus disease outbreak in Western Africa exemplifies this concern and underscores the need to have stronger health systems, equipped with health professionals trained to address both the acute and chronic demands for health care services in these settings (Doull and Campbell 2008; Boozary, Farmer, and Jha 2014; Horton 2014; Raguin and Eholie 2014). Health care provision in fragile states depends heavily on nongovernmental organizations, foreign government agencies, and international aid (Fujita et al. 2011). To date, little is reported about medical schools in times of fragility, particularly collectively across different geographic regions (Duvivier et al. 2014). However, medical schools and health training may provide one of the most sustainable solutions to delivery of health care in fragile states (Doull and Campbell 2008; Fujita et al. 2011). Overall, there is a lack of research examining the relationship between fragile states and medical schools.

We posit that fragile status has an independent association with number of medical schools. The instability of governance and institutional capacity contributes to an inability to invest in medical education and the health delivery system. Thus, fragile states may be perceived in the labor market as lacking the infrastructure to make a long‐term commitment to training and employment for both student and teaching candidates. Holding population and economic factors fixed, candidates for training or teaching in medical schools may therefore leave or refuse to enter the local labor market in fragile states due to these disincentives.

In this study, countries deemed fragile states by the World Bank were compared with nonfragile countries worldwide to understand the distributions of country‐level economic, demographic, and health indicators. We also explore whether fragile states have a disproportionately low number of medical schools and assess whether fragile status is associated with the number of medical schools after accounting for other measured factors. This could provide foundational evidence that fragile states are unlikely to train sufficient numbers of physicians for the future, based on currently available human resources for health and infrastructure.

Materials and Methods

Definitions

The World Bank's 2007 and 2012 lists of “Countries and Economies” were used. States were classified as fragile if they appeared on the World Bank's Harmonized List of Fragile Situations. All fragile states had an average Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) rating of ≤3.2 of 6 possible points or the presence of a United Nations and/or regional peacekeeping or peace‐building mission during the prior 3 years. The CPIA is an annually updated score developed by the World Bank to assess the capacity of a state to effectively use development support based on in‐country policies and institutions (World Bank 2012).

Data Extraction

Countries and economies were excluded from the analysis for the following reasons, defined prior to data collection: (1) total population <50,000 inhabitants, or (2) no available data on either life expectancy from the World Health Organization (WHO) or total population from the World Bank. Country‐level indicators were collected from the World Databank and WHO Global Health Observatory (World Bank 2015; World Health Organization 2015). We only include countries that were International Development Aid (IDA) eligible. Subnational conflicts and regions without statehood were not part of this study.

Information on medical schools was derived from the World Directory of Medical Schools, developed by the World Federation for Medical Education (WFME) and the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER), with the WHO and University of Copenhagen (World Directory of Medical Schools 2014). The World Directory defines a medical school as “an educational institution that provides a complete or full program of instruction leading to a basic medical qualification; that is, a qualification that permits the holder to obtain a license to practice as a medical doctor or physician.” We examine registered medical schools; it is known that nonregistered medical schools exist in fragile states, but, for various reasons, including organizational capacity, desire for registration, need for telecommunications, and lack of personnel, may not be listed in existing databases (Duvivier et al. 2014). All data on medical schools were extracted in May 2014.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for fragile states and nonfragile states based on status in 2007, the first year fragile status was available, and 2012, the most recent year available at the time of analysis. These descriptive analyses included an examination of states that transitioned from fragile status in 2007 to nonfragile status in 2012 and those that transitioned from nonfragile status in 2007 to fragile status in 2012. Standardized regression estimators were used to study the effect of fragile status in 2012, the most recent year available and therefore the most policy‐relevant classification, on the number of medical schools in 2014. Three regression models were considered, with all models including an indicator for fragile status. Model 1 was an unadjusted estimator and contained no additional covariates. Model 2 added the total population count on the logarithmic scale and population growth. Finally, Model 3 added gross national income (GNI) per capita and health expenditure per capita. The outcome variable, number of medical schools, was dichotomized given the sparsity of values >1 among fragile states. We considered binary outcomes for fewer than two schools as well as fewer than three schools.

The standardized regression approach was implemented given its flexibility and ease of interpretation; logistic regression models without standardization estimate the conditional odds ratio, whereas we were interested in the marginal relative risk. Logistic regression without any standardization does not identify marginal population‐level effects, and the parameters are thus not equivalent. Formally, the standardization regression estimator we implemented averages the logistic regression estimator over the estimated empirical distribution of the measured covariates to produce a marginal estimator and is also referred to as the g‐computation estimator (Robins 1986; van der Laan and Rose 2011; Snowden, Rose, and Mortimer 2011). Marginal effects are most often the parameters of interest in policy making decisions. Conditional regression coefficients and standard errors for the logistic regression models are also available (see Supplementary material, Appendix table).

Results

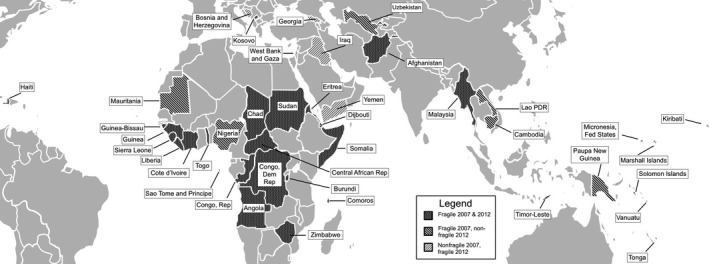

In 2007, there were 33 fragile states and 156 nonfragile states, and in 2012, there were 32 fragile states and 157 nonfragile states (Table 1). The total estimated population served by 189 medical schools in fragile states in 2007 was 501,545,969. Fragile states in 2007 and 2012, including those that transitioned in status, are shown geographically in Figure 1 (world map). There were 23 states that remained fragile between 2007 and 2012 (total population 296,718,020 in 2007 and 331,778,085 in 2012). In total, 70 percent of fragile states listed in 2007 remained fragile in 2012: Afghanistan, Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Eritrea, Guinea, Guinea‐Bissau, Haiti, Kosovo, Liberia, Myanmar, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, Sudan, Timor‐Leste, Togo, and Zimbabwe. States that transitioned from fragile to nonfragile status between 2007 and 2012 had economic, demographic, and health indicators more similar to countries fragile in 2012 than countries that were nonfragile in both 2007 and 2012. These countries that transitioned out of fragile status had higher median GNI per capita, health expenditures per capita, life expectancy, and physician density than countries classified as fragile in 2012, but not total population or number of reported medical schools. There were also eight states that were not fragile in 2007 and became fragile in 2012.

Table 1.

Country‐Level Economic, Demographic, and Health Indicators for Fragile and Nonfragile States

| WHO Region | Years Fragile | World Bank Income Group | Country | Total Population | GNI per Capita (USD) | Health Expenditure per Capita (USD) | Life Expectancy at Birth (Years) | Physician Density Per 1,000 (Year Reported) | No. Reported Operational Medical Schools‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 2007 | Low | Mauritania | 3,330,037 | 930 | 37 | 61 | 0.13 | 2009 | 0 |

| Lower‐middle | Nigeria | 147,187,353 | 970 | 81 | 50 | 0.41 | 2009 | 26 | ||

| Sao Tome and Principe | 163,390 | 850 | 66 | 65 | 0.49 | 2004 | 0 | |||

| 2007 & 2012 | Low | Burundi | 8,328,312 | 160 | 16 | 54 | 0.03 | 2004 | 1 | |

| Central African Republic | 4,106,897 | 400 | 18 | 46 | 0.05 | 2009 | 1 | |||

| Chad | 10,694,366 | 730 | 27 | 49 | 0.04 | 2006 | 1 | |||

| Comoros | 632,736 | 690 | 36 | 61 | 0.15 | 2004 | 1 | |||

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | 57,187,942 | 150 | 10 | 55 | 0.11 | 2004 | 7 | |||

| Eritrea | 5,209,846 | 240 | 8 | 60 | 0.05 | 2004 | 0 | |||

| Guinea | 10,046,967 | 310 | 26 | 54 | 0.10 | 2005 | 1 | |||

| Guinea‐Bissau | 1,484,337 | 440 | 29 | 53 | 0.07 | 2009 | 1 | |||

| Liberia | 3,522,294 | 160 | 21 | 57 | 0.01 | 2008 | 1 | |||

| Sierra Leone | 5,416,015 | 370 | 56 | 46 | 0.02 | 2010 | 1 | |||

| Togo | 5,834,806 | 410 | 28 | 55 | 0.05 | 2008 | 1 | |||

| Zimbabwe | 12,740,160 | 400 | – | 44 | 0.06 | 2009 | 1 | |||

| Lower‐middle | Angola | 17,712,824 | 2,560 | 115 | 49 | 0.17 | 2009 | 1 | ||

| Congo, Rep. | 3,758,858 | 1,390 | 57 | 56 | 0.10 | 2007 | 1 | |||

| Cote d'Ivoire | 17,949,061 | 990 | 72 | 49 | 0.14 | 2008 | 2 | |||

| Americas | 2007 & 2012 | Low | Haiti | 9,513,714 | 550 | 34 | 60 | 0.25 | 1998 | 5 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 2007 | Lower‐middle | Djibouti | 798,690 | – | 78 | 59 | 0.23 | 2006 | 0 |

| 2012 | Low | West Bank and Gaza | 3,494,496 | – | – | 72 | – | – | 0 | |

| Yemen, Rep. | 21,182,162 | 900 | 57 | 62 | 0.20 | 2010 | 6 | |||

| Lower‐middle | Iraq | 28,740,630 | 2,480 | 95 | 68 | 0.61 | 2010 | 16 | ||

| 2007 & 2012 | Low | Afghanistan | 26,349,243 | 330 | 30 | 58 | 0.23 | 2011 | 6 | |

| Somalia | 8,910,851 | – | – | 53 | 0.04 | 2006 | 1 | |||

| Lower‐middle | Sudan | 33,218,250 | 880 | 85 | 61 | 0.28 | 2008 | 26 | ||

| Europe | 2007 | Low | Uzbekistan | 26,868,000 | 760 | 46 | 68 | 2.38 | 2012 | 8 |

| 2012 | Lower‐middle | Georgia | 4,388,400 | 2,090 | 188 | 73 | 4.24 | 2012 | 13 | |

| Upper‐middle | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 3,868,665 | 3,730 | 341 | 75 | 1.69 | 2010 | 4 | ||

| 2007 & 2012 | Low | Kosovo | 1,733,404 | 2,730 | – | 69 | – | – | 2 | |

| Southeast Asia | 2007 & 2012 | Low | Myanmar | 50,828,959 | – | 7 | 64 | 0.61 | 2012 | 5 |

| 2007 & 2012 | Lower‐middle | Timor‐Leste | 1,046,030 | 1,800 | 41 | 66 | 0.07 | 2011 | 0 | |

| Western Pacific | 2007 | Low | Cambodia | 13,747,288 | 580 | 28 | 65 | 0.23 | 2008 | 2 |

| Lao PDR | 6,013,278 | 610 | 29 | 63 | 0.18 | 2012 | 1 | |||

| Lower‐middle | Papua New Guinea | 6,397,623 | 940 | 41 | 61 | 0.05 | 2008 | 1 | ||

| Tonga | 102,289 | 2,860 | 205 | 72 | 0.56 | 2010 | 1 | |||

| Vanuatu | 220,001 | 2,120 | 88 | 70 | 0.12 | 2008 | 1 | |||

| 2012 | Lower‐middle | Kiribati | 93,401 | 1,870 | 160 | 65 | 0.38 | 2010 | 0 | |

| Marshall Islands | 52,150 | 3,760 | 587 | – | 0.44 | 2010 | 0 | |||

| Micronesia, Fed. Sts. | 105,097 | 2,550 | 292 | 68 | 0.18 | 2009 | 1 | |||

| 2007 & 2012 | Lower‐middle | Solomon Islands | 492,148 | 1,030 | 67 | 66 | 0.22 | 2009 | 1 | |

| Nonfragile states (n = 148) | Median | 8,441,044 | 5,540 | 316 | 73 | 1.60 | 4 | |||

| Interquartile range | 24,073,331 | 14,363 | 876 | 9 | 2.42 | 9 | ||||

Population, GNI per capita (USD), health expenditure per capital (USD), and life expectancy (years) are 2007 figures. Physician density per 1,000 figures are the most recent available from the WHO Global Health Observatory (1998–2012).

‡No. of reported operational medical schools are current as of June 2014.

Figure 1.

Fragile and Nonfragile States in 2007 and 2012

Note. Fragile states exist in all parts of the world, although the African region is disproportionately represented.

Fragility, defined by fragile status in 2012, had an overall strong effect on having <2 or <3 medical schools, including after adjustment for potentially confounding variables: total population, population growth, GNI per capita, and health expenditure per capita (Table 2). Fragile states were 1.76–2.37 times more likely to have <2 medical schools than nonfragile states, depending on adjustment variables, and all relative risks were statistically significant. Similarly, fragile states were 1.27–1.76 times more likely to have <3 medical schools than nonfragile states, with all relative risks being statistically significant except the model with GNI per capita and health expenditure per capita. For countries with <2 medical schools, there was a median of seven physicians per 100,000 inhabitants in fragile states compared with 49 physicians in nonfragile states (p < .01). Similarly, the median number of physicians for countries with ≥2 medical schools was 26 in fragile states versus 183 in nonfragile states (p < .01). Median GNI per capita was 565 USD in fragile states with <2 medical schools and 945 USD for ≥2 medical schools. In contrast, median GNI per capita in nonfragile states was 3,190 USD and 5,560 USD for <2 and ≥2 medical schools, respectively.

Table 2.

Relative Risk Estimates for Having Fewer Than Two or Three Medical Schools, Respectively, in Fragile Versus Nonfragile States (n = 189)

| Variables Included | Fragile State | Log(Pop) | Pop Growth | GNI per Capita | Health Expenditure | Less Than Two Schools | Less Than Three Schools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR [95% CI] | RR [95% CI] | ||||||

| Model 1 | x | 2.37* [1.44, 3.30] | 1.73* [1.20, 2.26] | ||||

| Model 2 | x | x | x | 2.07* [1.32, 2.82] | 1.52* [1.09, 1.95] | ||

| Model 3 | x | x | x | x | x | 1.76* [1.07, 2.45] | 1.27 [0.85, 1.69] |

*Statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

CI, confidence interval; GNI, gross national income per capita; Log(Pop), logarithm of the total population in the country; RR, relative risk.

Discussion

In this analysis, we quantitatively assess the presence of medical schools in countries deemed to be fragile by the World Bank. When considering states that have two or fewer medical schools, the risk of being below this threshold is approximately two times higher if the state is fragile. This is true even after adjustment for some available indicators that are closely linked to fragility, including health expenditure per capita in a country. Indeed, a small number of states had no medical schools at all.

By quantifying the lack of medical training opportunities in fragile states, we aim to understand how fragile states lack the infrastructure to train sufficient numbers of physicians and, more long term, how they may not meet population‐level health goals. Physicians are among several health care workers needed to address international inequities in major health indicators. We focus on medical schools because of the comparative lack of information on nursing and public health schools and the present attempts to register medical schools worldwide. There is a high likelihood that schools for other health care workers are even more limited in number compared with medical schools in fragile states.

Several states in this analysis were either in armed conflict or emerging from conflict, including Afghanistan, Central African Republic, and Sudan. As the relationship between armed conflict and fragility is conceptually interlinked, many countries are both fragile and have a current or recent history of armed violence. Information specific to medical schools in armed conflict is anecdotal. One comprehensive report found that medical personnel and facilities were targeted in approximately 80 percent of countries in armed conflict between 2003 and 2008, but information specific to medical schools is unreported (Rubenstein and Bittle 2010).

This analysis also contributes to the growing recognition of Africa's health workforce crisis, but it focuses on states that are particularly vulnerable to it (Conway, Gupta, and Khajavi 2007; Mullan et al. 2011; Dalton 2014). One study, in 2007, found that an additional 820,000 doctors and nurses are needed in Africa to address “even the most basic health services.” In sub‐Saharan Africa, where many fragile states are located, the rate of increase in the number of physicians has not kept pace with the growing population or grown at the pace of low‐income countries elsewhere, such as India. Although several studies have concentrated on physician migration, relatively less has been studied on the number of training opportunities that exist and the low input of new physicians into the health sector. These shortages, among multiple other demands on weak health systems, exacerbate disease outbreaks such as HIV/AIDS and Ebola virus disease. Indeed, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia are all states fragile in both 2007 and 2012.

Our study has several strengths, including the novelty of the data extracted and analyzed, as well as the focus on population‐level parameters of interest to policy makers. We provide a global overview of the world's fragile states, across continents and geopolitical groups. These findings have several actionable results to implement change. We report that the number of medical schools is exceedingly small in most fragile states and the number of physicians per capita in these regions is disproportionately low. Because the fragility status designation is relatively new and has objective metrics, countries could be chosen internationally, which could not be done until 2006 when this information was first made publicly available by the World Bank. We also include new countries and countries outside of the African region.

Our work is also subject to specific limitations. The outcome of interest was based on the absolute number of reported registered schools but not on several other metrics of future interest. The student–faculty ratio, male‐female student and faculty ratios, number of academic disruptions due to violence and protests, fear of school attendance, and disparities in access to admissions—all anecdotally reported from various countries—cannot be officially studied through data collection (Sagher 2006; Rubenstein and Bittle 2010; Mullan et al. 2011; Asante, Roberts, and Hall 2012). The quality of medical education and graduating workforce would also be of high importance to study, and the World Directory of Medical Schools does not contain either of these metrics. This includes the range and breadth of the medical school curriculum, access to hands‐on clinical opportunities during training, and inclusion of topics such as gender‐based violence, trauma, and mental health. We also do not have data on unregistered medical schools. However, if our posited conceptual framework for the relationship between fragile status and number of medical schools is correct, our findings would likely hold if the number of unregistered medical schools had indeed been available.

This research supports the idea that establishing a sufficient workforce for health care delivery in fragile states is nontrivial. As many fragile states have a single medical school, there should be limited expectation that many will support their own health needs in the foreseeable future through existing operations. Based on our findings, we believe a focus on existing medical schools is important, given the strain on the relatively few schools that exist. “Twinning” of high‐ and low‐income schools internationally is proposed as a way to exchange ideas, curricula, and tangible products that can bilaterally improve education (Howard et al. 2007). Moreover, cooperation among medical school leadership in fragile states may lead to a more potent international presence and defined advocacy. Additionally, prospective characterization of faculty, students, and infrastructure—including perceived successes and obstacles—would enrich the understanding of the day‐to‐day operations of the few medical schools operating in fragile states.

Conclusion

Fragile status is a significant risk factor for having few medical schools. Existing medical schools lack the capacity to train sufficient numbers of physicians necessary to achieve population‐level health goals.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Coefficients and Standard Errors from Logistic Regressions.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This work was supported by The Canadian Physicians for Research and Education in Peace (CPREP) with student internship funding to EDM. The authors thank Thomas McGuire for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

References

- Asante, A. , Roberts G., and Hall J.. 2012. “A Review of Health Leadership and Management Capacity in the Solomon Islands.” Pacific Health Dialog 18: 166–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boozary, A. S. , Farmer P. E., and Jha A. K.. 2014. “The Ebola Outbreak, Fragile Health Systems, and Quality as a Cure.” Journal of the American Medical Association 312: 1859–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway, M. D. , Gupta S., and Khajavi K.. 2007. “Addressing Africa's Health Workforce Crisis.” The McKinsey Quarterly 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, S. C. 2014. “The Current Crisis in Human Resources for Health in Africa: The Time to Adjust Our Focus Is Now.” Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 108: 526–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doull, L. , and Campbell F.. 2008. “Human Resources for Health in Fragile States.” Lancet 371 (9613): 626–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvivier, R. J. , Boulet J. R., van Opalek A., Zanten M., and Norcini J.. 2014. “Overview of the World's Medical Schools: An Update.” Medical Education 48 (9): 860–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, N. , Zwi A. B., Nagai M., and Akashi H.. 2011. “A Comprehensive Framework for Human Resources for Health System Development in Fragile and Post‐Conflict States.” PLoS Medicine 8 (12): e1001146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton, R. 2014. “Offline: Can Ebola Be a Route to Nation‐Building?” Lancet 384: 2186. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, S. C. , Marinoni M., Castillo L., M. Bonilla , Tognoni G., Luna‐Fineman S., Antillon F., Valsecchi M. G., Pui C. H., Ribeiro R. C., Sala A., Barr R. D., Masera G.; and MISPHO Consortium Writing Committee. 2007. “Improving Outcomes for Children with Cancer in Low‐Income Countries in Latin American.” Pediatric Blood & Cancer 48 (3): 364–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan, M. , and Rose S.. 2011. Targeted Learning: Casual Inference for Observational and Experimental Data. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mullan, F. , Frehywot S., Omaswa F., E. Buch , Chen C., Greysen S. R., Wassermann T., Abubakr D. E., Awases M., Boelen C., Diomande M. J., Dovlo D., Ferro J., Haileamlak A., Iputo J., Jacobs M., Koumare A. K., Mipando M., Monekosso G. L., Olapade‐Olaopa E. O., Rugarabamu P., Sewankambo N. K., Ross H., Ayas H., Chale S. B., Cyprien S., Cohen J., Haile‐Mariam T., Hamburger E., Jolley L., Kolars J. C., Kombe G., and Neusy A. J.. 2011. “Medical Schools in sub‐Saharan Africa.” Lancet 26 (377): 1113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raguin, G. , and Eholie S.. 2014. “Ebola: National Health Stakeholders Are the Cornerstones of the Response.” The Lancet 384: 2207–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins, J. 1986. “A New Approach to Causal Inference in Mortality Studies with a Sustained Exposure Period‐Application to Control of Healthy Worker Survivor Effect.” Math Modeling 7: 1393–512. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein, L. S. , and Bittle M. D.. 2010. “Responsibility for Protection of Medical Workers and Facilities in Armed Conflict.” Lancet 375: 329–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagher, F. 2006. “What's Wrong with the Medical Education in Libya?” Jamahiriya Medical Journal 5: 80–2. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden, J. M. , Rose S., and Mortimer K. M.. 2011. “Implementation of G‐Computation on a Simulated Data Set: Demonstration of a Causal Inference Technique.” American Journal of Epidemiology 173: 731–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2012. “Harmonized List of Fragile Situations” [accessed on June 22, 2015]. Available at http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/brief/harmonized-list-of-fragile-situations

- World Bank . 2015. “World Databank” [accessed January 22, 2015]. Available at http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx

- World Directory of Medical Schools . 2014. “World Federation for Medical Education and Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research 2014” [accessed on January 22, 2015]. Available at http://www.wdoms.org

- World Health Organization . 2015. “Global Health Observatory Data Repository 2015” [accessed on January 22, 2015]. Available at http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Coefficients and Standard Errors from Logistic Regressions.