Abstract

Objective

To design and test the validity of a method to identify homelessness among Medicaid enrollees using mailing address data.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Enrollment and claims data on Medicaid expansion enrollees in Hennepin and Ramsey counties who also provided self‐reported information on their current housing situation in a psychosocial needs assessment.

Study Design

Construction of address‐based indicators and comparison with self‐report data.

Principal Findings

Among 1,677 enrollees, 427 (25 percent) self‐reported homelessness, of whom 328 (77 percent) had at least one positive address indicator. Depending on the type of addresses included in the indicator, sensitivity to detect self‐reported homelessness ranged from 30 to 76 percent and specificity from 79 to 97 percent.

Conclusions

An address‐based indicator can identify a large proportion of Medicaid enrollees who are experiencing homelessness. This approach may be of interest to researchers, states, and health systems attempting to identify homeless populations.

Keywords: Medicaid expansion, homelessness, determinants of health/population health/socioeconomic causes of health

Homelessness is a serious social problem affecting over half a million Americans on any given night (Henry et al. 2015). People who are homeless experience substantial morbidity and premature mortality (Bharel et al. 2013; Hwang and Burns 2014) and increased health care costs (Martell et al. 1992; Duchon, Weitzman, and Shinn 1999). The 2010 Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid to many previously uninsured homeless adults (Kaiser Family Foundation 2016; Vickery et al. 2016), while also funding cost‐reducing interventions to coordinate delivery of subsidized housing with health care (Larimer et al. 2009). Specific attention has focused on strategies to pair Medicaid services for physical and behavioral health conditions with permanent supportive housing (PSH), including through the Medicaid health home benefit (Doran, Misa, and Shah 2013; Wilkins, Burt, and Locke 2014; Health Affairs 2016).

Effective programs and research to improve the health of homeless Medicaid populations require accurate data to identify homeless individuals. Yet efforts to identify homeless Medicaid populations using secondary health care data in research or clinical care have been limited. Prior research efforts have relied on primary data collection during a health care or social service encounter (Gelberg, Andersen, and Leake 2000; Montgomery et al. 2013; Braciszewski, Toro, and Stout 2016) or on use of secondary databases of homeless service users maintained for administrative purposes (Byrne and Culhane 2015).

Prior work to identify homeless people within health care data has not been generalizable to Medicaid populations. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has focused on identifying homeless and at‐risk veterans as a part of their campaign to end veteran homelessness (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs). In addition to primary data collection using a screening tool in the electronic health record (Montgomery et al. 2013), VA researchers have examined secondary data indicating use of VA‐supported homeless services and/or diagnoses of lack of housing (Edens et al. 2011). They have also used natural language processing to examine free text within VA medical records indicative of homelessness (Gundlapalli et al. 2013). Recent work in New York City has attempted to identify homelessness at the population level using text or addresses that might be proxies for homelessness or unstable housing. Data came from the addresses provided by patients using health care services in a regional health information exchange and were not compared to self‐report or another source (Zech et al. 2015). While notable, none of these efforts captures a population‐level estimate of homelessness, and none was widely adopted.

In this study, we developed and tested a homeless address indicator using Medicaid data. We partnered with local homelessness experts in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, who observed consistent patterns of mailing addresses used by homeless people in health care encounters including in Medicaid enrollment. We examined data from a group suspected to include many people experiencing homelessness: Minnesota's urban early Medicaid expansion population of adults without dependent children and income ≤75 percent poverty (Anon 2010; State of Minnesota Executive Department 2011). First, we created indicators to identify adults experiencing homelessness using Medicaid enrollment mailing addresses. Second, we assessed the specificity and sensitivity of the indicators for identifying homeless persons by comparing them to self‐reported homelessness on a psychosocial needs assessment.

Methods

Data Sources and Study Cohort

We obtained Medicaid enrollment and claims data from March 2011 through December 2014 from the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS) on adult enrollees without dependents with at least 1 month of eligibility in Hennepin and Ramsey counties for purposes of another study. Medicaid enrollment data included age, race, ethnicity, primary language, education, and up to six historical mailing addresses. We identified a subset of this cohort who completed the Life Style Overview (LSO) in 2011–2014.

The LSO is a verbally administered psychosocial screening tool administered to patients deemed to have multiple needs during visits to Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC) and affiliate sites. The LSO includes the question, “Where are you living today?” with possible response categories of homeless, shelter, at a relative or friend's place, and your house or apartment adapted from the Homeless Supplement to the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (North et al. 2004). In this study, following the point‐in‐time definition of homelessness used by the National Alliance to End Homelessness (National Alliance to End Homelessness 2016), we defined LSO‐homelessness as responses of either homeless or shelter. This definition was preferred to other federal definitions of homelessness (Anon 2009) as it offered better alignment with the point‐in‐time LSO question.

Construction of Homeless Address Indicators

The homeless address indicators were based on six sources: (1) a comprehensive directory of shelter and single‐site supportive housing programs provided by housing program staff from Hennepin and Ramsey Counties in response to an open‐ended inquiry by electronic mail. We added several other address types noted by local homeless experts to this directory, including (2) the General Delivery Address (GDA)— a free service offered by the U.S. Postal Service for an individual's mail to be held at the post office; (3) addresses of local homeless service centers collecting mail for homeless clients; (4) free text responses (e.g., “homeless”) recorded in the mailing address section of Medicaid enrollment records synonymous with homelessness; and (5) addresses of institutions commonly used by homeless individuals, including hotels, places of worship, and hospitals (Zech et al. 2015). Finally, (6) within the data, we observed frequent use of the addresses of county administrative offices and added these locations to the directory.

Because individuals residing in permanent supportive housing (PSH) more often report having their own apartment/house and are more stably housed, PSH addresses were excluded from the homeless address indicators.

The homeless address indicators were created to identify the presence of any homeless addresses in Medicaid enrollment records. We matched the indicators to the enrollment address file using ArcGIS, version 10.2.1 (ESRI). To understand the reliability of the GDA alone in indicating homelessness, this was analyzed separately from the non‐GDA homeless addresses (see Appendix SA2).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Minnesota Department of Human Services and Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation.

Analysis

We grouped homeless addresses into descriptive categories with input from Hennepin County housing program staff. We counted the number of unique addresses in each category. To determine the accuracy of the homeless address indicators, we matched date ranges for use of Medicaid enrollment addresses with date of response to the LSO housing question.

We described the demographic characteristics of Medicaid enrollees using descriptive statistics and compared the enrollees who were LSO‐homeless to nonhomeless groups using t‐tests with unequal variance adjustments and chi‐square tests.

To assess accuracy of address‐based indicators to self‐report, we used three simple logistic regression models. We regressed self‐reported LSO homelessness first on the indicator for GDA, second on the indicator for non‐GDA homeless addresses, and third on an indicator of use of either the GDA or non‐GDA homeless address in Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp 2011). We employed robust standard errors to account for correlated observations within persons due to enrollees’ multiple LSO responses and multiple addresses over time. Using estimates from each model, we calculated marginal adjusted probabilities of self‐reporting homelessness. We calculated sensitivity, specificity, and negative and positive predictive values and used a c‐statistic and area under the receiver operator characteristic curve to assess fit of each model.

Results

We grouped the primary homeless address lists provided by county housing program staff into the following address categories: emergency shelters (22 unique addresses), board and lodge facilities (60), and transitional housing sites (30). We included additional institutional addresses that may be used by homeless people, including places of worship (208), hotels (111), hospitals (11), and social service sites and drop‐in centers (8) in the seven‐county metropolitan region (see Appendix SA2). In total, the homeless address indicator included 450 unique addresses.

We found 1,677 unique enrollees with time‐matched enrollment address indicators and answers to the LSO “living today” question. Some participants took the LSO more than once between 2011 and 2014; overall, respondents answered the housing question 1 to 4 times (mean 1.1, median 1, standard deviation 0.31, range 1–4). The cohort was predominantly male, English‐speaking, and black (see Table S1).

One‐quarter of unique, responding Medicaid enrollees (n = 427, 25 percent) reported LSO‐homelessness by responding “shelter” or “homeless” one or more times to the LSO instrument's housing question. These individuals were most likely to use the GDA (Table 1) but also used a variety of non‐GDA homeless addresses (Table S2). Of these 427 LSO‐homeless Medicaid enrollees, over three quarters (n = 328, 77 percent unique people or n = 339 addresses) used one or more addresses included in the homeless address indicators to enroll in Medicaid during the study period.

Table 1.

Type of Homeless Addresses Used by Urban Early Medicaid Expansion Enrollees,a 2011–2014

| Homeless, by Self‐Report | Not Homeless, by Self‐Report | All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| No homeless address | 107 | 24 | 1,076 | 79 | 1,183 | 65 |

| General delivery address (GDA) | 207 | 46 | 243 | 18 | 450 | 25 |

| Non‐GDA homeless addressb | 132 | 30 | 46 | 3 | 178 | 10 |

| Either GDA or non‐GDA homeless address | 339 | 76 | 289 | 21 | 628 | 35 |

| Total sample | 446 | 100 | 1,365 | 100 | 1,811 | 100 |

Data reported at the address level. Individuals could use more than one address type over time.

Homeless addresses included emergency shelters, board and lodge facilities, transitional housing, social service sites, drop‐in centers, places of worship, hotels, and hospitals. See Table S2 for frequency of use by category.

Source: Authors analyzes of Minnesota Department of Human Services enrollment and claims data and homeless address directory constructed by our research team.

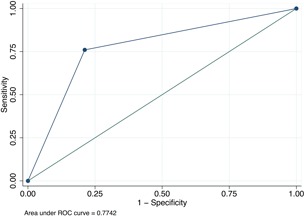

Enrollees using the GDA had a 46 percent probability of reporting homelessness on the LSO. The GDA indicator had a sensitivity of detecting self‐reported homelessness of 46 percent with a specificity of 82 percent (C‐statistic = 0.64). Enrollees using the non‐GDA homeless address indicator had a 74 percent probability of reporting homelessness on the LSO. The sensitivity of the non‐GDA indicator was 30 percent with a specificity of 97 percent (C‐statistic = 0.63). When combined, enrollees using either the GDA or a non‐GDA homeless address had a 54 percent probability of self‐reported homelessness. The combined indicator had a 76 percent sensitivity and 79 percent specificity with a 54 percent positive predictive value and 91 percent negative predictive value (C‐statistic = 0.77) (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Probability of Self‐Reported Homelessness with Use of Homeless Addresses on Medicaid Enrollment Forms

| Probability of Self‐Reported Homelessness on Life Style Overview | Sensitivity of Homeless Address on Medicaid Enrollment Forms to Detect Self‐Reported Homelessness | Specificity of Homeless Address on Medicaid Enrollment Forms to Detect Self‐Reported Homelessness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of only general delivery address (GDA) | 46% | 46% | 82% |

| Use of non‐GDA homeless address | 74% | 30% | 97% |

| Use of either GDA or non‐GDA homeless address | 54% | 76% | 79% |

Source: Authors analyzes of Minnesota Department of Human Services enrollment and claims data; self‐reported Life Style Overview data from Hennepin County Medical Center electronic health record.

Figure 1.

- Source: Authors analyzes of Minnesota Department of Human Services enrollment and claims data and self‐reported Life Style Overview data from Hennepin County Medical Center electronic health records.

- Note: *Indicator of use of either general delivery address (GDA) or non‐GDA homeless address.

Discussion

Our study offers a new approach to measuring homelessness at the population level using existing, secondary data from Medicaid enrollment records. In contrast to prior efforts to identify homeless populations, enrollment data are collected on all people who register for health insurance and are not limited to the subset who use health care or social services. Our homeless address indicators identified self‐report of homelessness with consistently high specificity among early Medicaid expansion enrollees in our sample. This means that enrollees who have the homeless address indicators are likely to self‐report homelessness and increases confidence in utilizing this approach to identify homeless Medicaid enrollees in our region. Our findings may have been strengthened by including housing addresses observed by local, frontline homeless service providers. However, the variable sensitivity of our indicators suggests that more work is needed to develop comprehensive measures to accurately identify Medicaid enrollees at risk for homelessness.

Our work builds upon previous research using self‐reported address as a marker for unstable housing and health risk but shows that homeless address indicators must be customized to match the local environment. For example, Zech et al. found hospital address to be the most consistently used homeless address type (Zech et al. 2015), while in our study region, the GDA was the most commonly used homeless address. The preponderance of GDA use in our sample suggests regional variation in address patterns indicating homelessness.

Our study has several limitations. First, measurement of homelessness is complex, and there is no single standardized approach (National Coalition for the Homeless 2007). This may be reflected in the low sensitivity of our indicators, which do not reliably capture all people experiencing the spectrum of unstable housing. The point‐in‐time LSO question does not align with the widely accepted federal definition of people eligible to receive homeless assistance from the HEARTH Act (Anon 2009; Department of Housing and Urban Development). The LSO question reflects one of many approaches to screening for housing status in health care settings and may underestimate true homelessness in several key ways. First, self‐reported homeless screening questions in clinical settings may suffer from response bias due to stigma and other factors (DiPietro and Edgington 2016). Second, the LSO question represents a point‐in‐time estimate by asking only where respondents were “living today.” Similar to national point‐in‐time homeless estimates (Sumner et al. 2001; National Alliance to End Homelessness 2016), this may miss populations cycling in and out of homelessness. However, prior research suggests that a question about where homeless persons slept last night missed less than 5 percent of those who reported being homeless at some point in the last 30 days (Sumner et al. 2001). Third, we chose not to include people in the LSO sample who responded that they were “staying with relatives or friends.” While these “doubled up” respondents represent a significant population at risk for homelessness, our homeless address indicators could not accurately identify this group. Similarly, the homeless address indicators may underestimate homelessness for several different reasons. First, housing support sites may close or move over time. Second, variation in spelling of addresses may limit accuracy of matching. Third, we excluded PSH sites, which are included in the federal definition of homeless eligibility. Finally, our nonrandom sample was screened with the LSO based on the assessment of frontline clinical staff of complex needs and included only adults without dependents. This limits the generalizability of these findings to other homeless populations or other regions.

Further work is needed to develop and test ideal homelessness screening tools for use in clinical settings or during Medicaid enrollment. Clinical tools could work in conjunction with measures derived from secondary data available within databases maintained by homeless service providers. Regular maintenance of address lists would be avoided with use of shelter and supportive housing records from the national Housing Inventory Count Reports or the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) maintained by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The Housing Inventory Count Reports maintains an annually updated list of the names and addresses of federally subsidized shelters and other supportive housing sites (HUD 2017). And HMIS tracks use of such facilities at the individual and family level (HUD 2016). In spite of significant challenges and some limitations (Gutierrez and Friedman 2005), the reports and HMIS represent nationally mandated, locally administered datasets tracking the homeless population. Linkage to these housing services databases could allow for more robust identification of supportive housing locations and add frequency measures of their use by individuals enrolled in Medicaid, a level of detail not available from our address indicator. We found no previous work that paired HUD databases with Medicaid or health care data for research or practice.

Accurately identifying homeless individuals is the first step in delivering targeted, evidence‐based interventions to improve outcomes and control costs in homeless populations (O'Toole et al. 2010, 2016). While a comprehensive indicator is ideal, indicators with high specificity using existing secondary data at the population level may be useful as a transitional step. Increasing evidence supports the value of “housing as health care,” with recent policies encouraging the use of Medicaid dollars to support integration of housing with medical and behavioral health care (Doran, Misa, and Shah 2013; Wilkins, Burt, and Locke 2014). Medicaid expansion has increased the insurance coverage of homeless and formerly homeless individuals (Kaiser Family Foundation 2016; Vickery et al. 2016), making improved outcomes and cost control especially important for participating states. With proposed cuts to federal support for Medicaid (Congressional Budget Office 2017), potential strategies for cost control in homeless Medicaid populations may also be of increasing importance.

Conclusion

Existing address data within Medicaid enrollment records identified self‐reported homeless populations in one urban region with high specificity. This and other identification strategies may allow for improved research and care delivery to reduce premature morbidity and mortality disproportionately faced by homeless populations.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Technical Appendix.

Table S1: Comparison of Characteristics of Self‐Reported Homeless to Non‐Homeless Medicaid Expansion Enrollees on Life Style Overview (LSO).

Table S2: Types of Non‐General Delivery Homeless Addresses Used by Early Medicaid Expansion Recipients.*

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This project was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program during Dr. Vickery's early work. Dr. Vickery's subsequent work was supported by a career development award through Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation. The work of Drs. Vickery and Shippee and Ms. Guzman‐Corrales and receipt of the data set used in this study was supported by the Commonwealth Fund, grant no. 2014076 (PI: ND Shippee).

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimer: None.

References

- Anon . 2009. “HEARTH Act of 2009,” S.896. Available at https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/S896_HEARTHAct.pdf

- Anon . 2010. “Minn. Session Laws §16 Section 5 (2010).” Available at https://www.revisor.leg.state.mn.us/laws/?year=2010&type=1&doctype=Chapter&id=1

- Bharel, M. , Lin W.‐C., Zhang J., O'Connell E., Taube R., and Clark R. E.. 2013. “Health Care Utilization Patterns of Homeless Individuals in Boston: Preparing for Medicaid Expansion under the Affordable Care Act.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (S2): S311–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braciszewski, J. M. , Toro P. A., and Stout R. L.. 2016. “Understanding the Attainment of Stable Housing: A Seven‐Year Longitudinal Analysis of Homeless Adolescents.” Journal of Community Psychology 44 (3): 358–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, T. , and Culhane D. P.. 2015. “Testing Alternative Definitions of Chronic Homelessness.” Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 66 (9): 996–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office . 2017. “American Health Care Act Budget Reconciliation Recommendations of the House Committees on Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce.” Available at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52486

- Department of Housing and Urban Development . “Homeless Definition,” HUD Exchange [accessed on November 22, 2016]. Available at https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/HomelessDefEligibility%20_SHP_S PC_ESG.pdf

- DiPietro, B. , and Edgington S.. 2016. “Ask & Code: Documenting Homelessness Throughout the Health Care System,” National Health Care for the Homeless Council. Available at https://www.nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ask-code-policy-brief-final.pdf

- Doran, K. M. , Misa E. J., and Shah N. R.. 2013. “Housing as Health Care: New York's Boundary‐Crossing Experiment.” New England Journal of Medicine 369 (25): 2374–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchon, L. M. , Weitzman B. C., and Shinn M.. 1999. “The Relationship of Residential Instability to Medical Care Utilization among Poor Mothers in New York City.” Medical Care 37 (12): 1282–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens, E. L. , Kasprow W., Tsai J., and Rosenheck R. A.. 2011. “Association of Substance Use and VA Service‐Connected Disability Benefits with Risk of Homelessness among Veterans.” American Journal on Addictions/American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions 20 (5): 412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESRI . ArcGIS. Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg, L. , Andersen R. M., and Leake B. D.. 2000. “The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: Application to Medical Care Use and Outcomes for Homeless People.” Health Services Research 34 (6): 1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlapalli, A. V. , Carter M. E., Palmer M., Ginter T., Redd A., Pickard S., Shen S., South B., Divita G., Duvall S. L., Nguyen T. M., D'Avolio L. W., and Samore M. H.. 2013. “Using Natural Language Processing on the Free Text of Clinical Documents to Screen for Evidence of Homelessness Among US Veterans.” AMIA … Annual Symposium proceedings/AMIA Symposium. AMIA Symposium, 2013 Available at https://utah.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/using-natural-language-processing-on-the-free-text-of-clinical-do [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, O. , and Friedman D. H.. 2005. “Managing Project Expectations in Human Services Information Systems Implementations: The Case of Homeless Management Information Systems.” International Journal of Project Management 23 (7): 513–23. [Google Scholar]

- Health Affairs . 2016. Medicaid and Permanent Supportive Housing. Health Policy Briefs Available at http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=164 [Google Scholar]

- Henry, M. , Shivji A., de Sousa T., and Cohen R.. 2015. “The 2015 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress,” The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Office of Community Planning and Development [accessed on April 20, 2016]. Available at https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

- HUD . 2016. “Homeless Management Information System” [accessed on March 26, 2016]. Available at https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/hmis/

- HUD . 2017. “CoC Housing Inventory Count Reports – HUD Exchange” [accessed on March 27, 2017]. Available at https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/coc/coc-housing-inventory-count-reports/

- Hwang, S. W. , and Burns T.. 2014. “Health Interventions for People Who Are Homeless.” Lancet (London, England), 384 (9953): 1541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation . 2016. “How Has the ACA Medicaid Expansion Affected Provider Serving the Homeless Population: Analysis of Coverage, Revenues, and Costs.” The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured [accessed on June 9, 2016]. Available at http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-how-has-the-aca-medicaid-expansion-affected-providers-serving-the-homeless-population.

- Larimer, M. E. , Malone D. K., Garner M. D., Atkins D. C., Burlingham B., Lonczak H. S., Tanzer K., Ginzler J., Clifasefi S. L., Hobson W. G., and Marlatt G. A.. 2009. “Health Care and Public Service Use and Costs before and after Provision of Housing for Chronically Homeless Persons with Severe Alcohol Problems.” Journal of the American Medical Association 301 (13): 1349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell, J. V. , Seitz R. S., Harada J. K., Kobayashi J., Sasaki V. K., and Wong C.. 1992. “Hospitalization in an Urban Homeless Population: The Honolulu Urban Homeless Project.” Annals of Internal Medicine 116 (4): 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, A. E. , Fargo J. D., Byrne T. H., Kane V. R., and Culhane D. P.. 2013. “Universal Screening for Homelessness and Risk for Homelessness in the Veterans Health Administration.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (S2): S210–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness . 2016. The State of Homelessness in America. Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness; [accessed on November 22, 2016]. Available at http://www.endhomelessness.org/page/-/files/2016%20State%20Of%20Homelessness.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition for the Homeless . 2007. “How Many People Experience Homelessness?” [accessed on April 12, 2016]. Available at http://www.nationalhomeless.org/publications/facts/How_Many.pdf

- North, C. S. , Eyrich K. M., Pollio D. E., Foster D. A., Cottler L. B., and Spitznagel E. L.. 2004. “The Homeless Supplement to the Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Test‐Retest Analyses.” International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13 (3): 184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole, T. P. , Buckel L., Bourgault C., Blumen J., Redihan S. G., Jiang L., and Friedmann P.. 2010. “Applying the Chronic Care Model to Homeless Veterans: Effect of a Population Approach to Primary Care on Utilization and Clinical Outcomes.” American Journal of Public Health 100 (12): 2493–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole, T. P. , Johnson E. E., Aiello R., Kane V., and Pape L.. 2016. “Tailoring Care to Vulnerable Populations by Incorporating Social Determinants of Health: The Veterans Health Administration's ‘Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team’ Program.” Preventing Chronic Disease 13: E44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- State of Minnesota Executive Department . 2011. Executive Order 11‐01, Available at http://www.leg.mn/archive/execorders/11-01.pdf

- Sumner, G. C. , Andersen R. M., Wenzel S. L., and Gelberg L.. 2001. “Weighting for Period Perspective in Samples of the Homeless.” American Behavioral Scientist 45 (1): 80–104. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs . “About the Initiative – Homeless Veterans” [accessed on April 12, 2016]. Available at http://www.va.gov/homeless/about_the_initiative.asp

- Vickery, K. D. , Guzman‐Corrales L., Owen R., Soderlund D., Shimotsu S., Clifford P., and Linzer M.. 2016. “Medicaid Expansion and Mental Health: A Minnesota Case Study.” Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare 34 (1): 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, C. , Burt M., and Locke G.. 2014. “A Primer on Using Medicaid for People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness and Tenants in Permanent Supportive Housing.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging, and Long‐Term Care Policy [accessed on April 20, 2016]. Available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/77121/PSHprimer.pdf

- Zech, J. , Husk G., Moore T., Kuperman G. J., and Shapiro J. S.. 2015. “Identifying Homelessness Using Health Information Exchange Data.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 22 (3): 682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Technical Appendix.

Table S1: Comparison of Characteristics of Self‐Reported Homeless to Non‐Homeless Medicaid Expansion Enrollees on Life Style Overview (LSO).

Table S2: Types of Non‐General Delivery Homeless Addresses Used by Early Medicaid Expansion Recipients.*