Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common in dogs, but evidence of efficacy of its treatment is lacking.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of fenoldopam in the management of AKI.

Animals

Forty dogs with naturally occurring heatstroke.

Methods

Dogs were prospectively enrolled and divided into treatment and the placebo groups (fenoldopam, constant rate infusion [CRI] of 0.1 µg/kg/min or saline, respectively). Urine production (UP) was measured using a closed system. Urinary clearances were performed at 4, 12, and 24 hours after presentation to estimate the effect of fenoldopam on UP, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and sodium fractional excretion (NaFE).

Results

At presentation, severity of heatstroke, based on a previously developed scoring system, was similar between the study groups, but was significantly worse in nonsurvivors compared with survivors. Fenoldopam administration was not associated with hypotension. Overt AKI was diagnosed, based on the International Renal Interest Society guidelines in 22/40 (55%) of the dogs. Overall, 14/40 dogs (35%) died, with no significant (P = .507) mortality rate difference between the fenoldopam (6/20 dogs; 30%) and placebo (8/20; 40%) groups. The proportion of dogs with AKI did not differ between the fenoldopam and the placebo groups (9/20; 45% versus 13/20; 65%, respectively; P = .204). There were no differences in UP, GFR, and NaFE between the fenoldopam and the placebo groups.

Conclusion and Clinical Importance

Fenoldopam CRI at 0.1 µg/kg/min did not have a clinically relevant effect on kidney function parameters in dogs with severe heatstroke‐associated AKI.

Keywords: acute renal failure, canine, dopamine, hypotension, renal

Abbreviations

- ABP

arterial blood pressure

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- CRI

constant rate infusion

- DA‐1

dopamine‐1–receptor

- DAP

diastolic ABP

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IRIS

International Renal Interest Society

- MAP

mean ABP

- NaFE

sodium fractional excretion

- PP

postpresentation

- SAP

systolic arterial blood pressure

- sCr

serum creatinine

- SD

standard deviation

- UP

urine production

- VTH

veterinary teaching hospital

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) in dogs is characterized by a sudden decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), decreased urine production (UP) and alterations in solute excretion.1 Acute kidney injury leads to high morbidity and mortality, which are influenced mainly by the underlying etiology and therapeutic options.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The therapeutic approach for AKI generally is supportive, aimed at eliminating the underlying cause and correcting the hemodynamic and biochemical consequences of the attendant uremia.10 When medical management fails to control clinical and laboratory abnormalities, more advanced therapy, such as hemodialysis, can be applied, if available.9

Low‐dose dopamine therapy has been suggested as a treatment for AKI in human patients. Although past studies yielded conflicting results, recent evidence suggests that low‐dose dopamine has no role in prevention and management of AKI.11, 12, 13, 14 Fenoldopam is a selective dopamine‐1–receptor (DA‐1) agonist, inducing vasodilatation, and selectively increasing both renal cortical and outer medullary blood flow and GFR, similar to dopamine.15, 16, 17 Unlike dopamine, fenoldopam is not associated with adverse effects resulting from α‐ and β‐adrenergic receptor activation. A recent large‐scale study evaluating fenoldopam for prevention of contrast‐induced nephropathy in human patients failed to show an advantage of its use.18 Conversely, a study of AKI in human patients in intensive care units (ICU) demonstrated that fenoldopam (CRI of 0.09 µg/kg/min IV) led to a significant decrease in the occurrence of AKI.19 Yet another study failed to show similar effects.20 Finally, a recent meta‐analysis, including studies of fenoldopam in human patients in ICU and those undergoing major surgery concluded that fenoldopam significantly decreased the risk for AKI, the need for renal replacement therapy, and the mortality rate.21 The latter study, however, excluded contrast‐induced nephropathy, and included only a few placebo‐controlled trials, in which fenoldopam doses varied, and thus was limited. A recent review of the current knowledge on prevention of AKI has concluded that the role of fenoldopam in preventing AKI warrants further exploration, because there is still a lack of controlled clinical studies evaluating its clinical efficacy, and its use for preventing AKI in human patients at risk for AKI remains controversial.22 The efficacy of fenoldopam as preventive therapy for AKI in animals at high risk for AKI has not been evaluated in a controlled study, and evidence regarding its efficacy in animals with AKI is limited. In a retrospective study of dogs and cats with AKI, fenoldopam had no beneficial effects, but its effects on UP, GFR, and solute excretion were not evaluated.23

Heatstroke in dogs results from exposure to a hot environment or strenuous physical exercise, leading to high body core temperature (>41°C) and central nervous system dysfunction.6 Regardless of the insult, heatstroke leads to severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome, multiple organ dysfunction, and often death.6 Acute kidney injury is a common complication of heatstroke, in both dogs and humans,6, 24, 25, 26 probably resulting from hemodynamic instability.25, 27 Necropsy results of dogs sustaining fatal heatstroke and measurement of sensitive markers of kidney damage in dogs with heatstroke show that AKI invariably is present in affected animals,28 and is a risk factor for death.6 For these reasons, heatstroke is an excellent model for naturally occurring AKI in dogs, and can be used to test a variety of therapeutic and preventive interventions in AKI.

We hypothesized that fenoldopam would increase GFR, UP, and sodium fractional excretion (NaFE) in dogs with naturally occurring heatstroke. The aim of this prospective, placebo‐controlled study was to investigate the efficacy of fenoldopam for decreasing the occurrence and severity of heatstroke‐associated AKI in dogs, and potentially preventing heatstroke‐induced AKI. Specifically, we sought: (1) to assess the influence of fenoldopam on sequential changes in GFR, UP, and NaFE; (2) to assess the proportion of AKI in dogs receiving fenoldopam versus placebo; and (3) to assess if fenoldopam would decrease the death rate in dogs naturally sustaining heatstroke.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and randomization

This prospective, randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled clinical trial was approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (KSVM‐VTH/13–2009). Dogs presented to the Hebrew University Veterinary Teaching Hospital (VTH) between 2009 and 2015 and diagnosed with heatstroke were considered eligible for the study, depending on their owners' consent.

Randomization was performed by drawing slip from an envelope indicating the treatment regimen. Envelopes were prepared by the VTH chief pharmacist, and investigators, attending clinicians, staff, and dog owners were blinded to the treatment regimen until the end of the study. Fenoldopam (Fenoldopam, Corlopam, 20 mg/2 mL, Teva, Milano) or saline (as placebo) were dispensed in identical syringes.

2.2. Case selection

Dogs presented to the Emergency Service of the VTH and diagnosed with heatstroke were consecutively enrolled. Heatstroke was diagnosed based on a history of exposure to a hot environment, strenuous activity, or both, and presence of appropriate clinical signs, which had developed acutely only after the heat insult, including neurological dysfunction, collapse, and tachypnea. Dogs with coexisting medical conditions, and those that died or were euthanized within 4 hours of hospitalization, were excluded.

2.3. Definitions

The diagnosis of AKI was made according to International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) guidelines.29 Dogs that died or were euthanized because of grave prognosis, despite ongoing intensive therapy, were defined as nonsurvivors.

2.4. Treatment protocol and monitoring

Dogs enrolled in the study were treated and managed according to a previously described protocol for heatstroke.6 Upon admission, the urinary bladder was catheterized, and the catheter connected to a closed urinary system. Urine production was monitored and recorded q4h during the first 24 hours after presentation. Dogs were treated initially with crystalloid fluids as an IV bolus, at 30 mL/kg and, as needed to correct hypovolemia and shock, if present, and thereafter, as needed to restore all fluid deficits over a period of 4 hours. Once hypovolemia and dehydration were corrected, IV fluid therapy was continued initially at 5 mL/kg/h, and thereafter adjusted to meet ongoing fluid loss (eg, diarrhea and vomiting), and based on UP, periodic physical assessment of hydration status, and body weight measurement, to maintain normal hydration throughout hospitalization.

Dogs received mannitol (20% Osmitrol, Baxter, Deerfield, Illinois; IV bolus, 0.5 g/kg over 20 min) q4h over the first 12 hours from admission to prevent and treat potential brain edema, a common complication of heatstroke.6, 25 Dogs also were given ampicillin (Penibrin, Sandoz GmbH, Kundl Austria; 20 mg/kg IV q8h) and enrofloxacin (Baytril, 5%, Bayer Animals Health Leverkusen; 15 mg/kg slow IV q24h) to prevent and treat gastrointestinal bacterial translocation, and famotidine (Famotidine, West‐Ward, Eatontown, New Jersey; 0.5 mg/kg IV q24h) and metoclopramide (Metoclopramide. Pramin 10MG/2ML Rafa Laboratories, Jerusalem; 0.04 mg/kg/h IV by CRI) to prevent and treat gastric ulceration and vomiting, respectively.

Fenoldopam (study group) or saline (placebo group) was initiated 4 hours post‐presentation (PP), after verifying that systolic arterial blood pressure (SAP) was >120 mm Hg. Fenoldopam and saline placebo were diluted in 100 mL of saline. Fenoldopam was administered IV at a CRI of 0.1 µg/kg/min, whereas the placebo group was given saline at identical dilution and rate.

Urine volume was measured gravimetrically q4h. Urine samples were obtained q4h and stored at −80°C pending analysis. Measurements included body weight, UP, serum, and urine chemistry, GFR (estimated by endogenous creatinine clearance) and urinary NaFE.

Arterial blood pressure (ABP) was measured using oscillometry (Cardell, Midmark, Tampa, FL) q4h. A previously described scoring system for heatstroke was used.30

2.5. Urinary clearances

Urine and blood samples were collected to calculate NaFE and creatinine clearance at 4, 12, and 24 hours PP, to estimate GFR and NaFE, as previously described.31, 32, 33 Briefly, 2 sequential 30‐minute quantitative urine collections were performed each time, to assess GFR and NaFE. Blood was collected in plain tubes with gel separators when the first urine sample was collected, and when the second urine sample collection ended. The urinary bladder was emptied and irrigated 3 times with 10 mL of sterile water, at the start and end of each urine collection. The urinary bladder rinse volume, at the end of each urine collection period, was added to the urine volume collected. The urine volume of each urine collection was measured gravimetrically. Urine sample aliquots were stored at −80°C pending analysis. Blood samples were allowed to clot, centrifuged, and serum chemistry analysis (Cobas Integra 400 Plus, Roche, Mannheim, Germany; at 37°C) was performed within 60 minutes from collection, including urea, creatinine (sCr), and sodium. The results for the two individual 30‐minute clearances were averaged to provide an estimate of the renal clearance of solutes.

The renal clearance (C), and FE of solute (x) were calculated conventionally,1 where Cx = Ux V/Px and FEx = Cx/Ccr, where Cx = clearance of solute x; Ccr = clearance of creatinine (mL/min); V = urine volume (mL/min); Ux = urine solute (x) concentration; Px = serum solute (x) concentration.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to document sequential changes in kidney function tests and solute FE throughout the study period. The distribution pattern of continuous variables was examined using the Shapiro‐Wilk test. Continuous variables (eg, UP and GFR) were reported as mean ± SD or median and range, and compared between groups using the Student t‐test and the Mann Whitney U‐test, for normally and non‐normally distributed data, respectively. Categorical variables (eg, proportions) were compared between groups using χ2 or Fisher Exact tests. The Friedman test was used to assess changes in continuous variables over the first 24 hours PP. All tests were 2‐tailed, and P < .05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using a statistical software package (SPSS 22.0 software, Chicago, Illinois).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Dogs

The study included 40 dogs, 20 in each treatment group. There were 33 males (neutered, 7) and 7 females (neutered, 4). There was no mean age difference (P = .747) between the fenoldopam (4.6 ± 2.7 years) and placebo (4.4 ± 2.3 years) groups. The study included 13 brachycephalic dogs (32.5%), including boxer (6 dogs), French bulldog (4), Pug (2), and English bulldog (1). There were 37 dolichocephalic dogs (67.5%), including mixed breed (6 dogs), golden retriever (4), Belgian Malinois (4), Labrador retriever (3), Samoyed, German shepherd and Siberian husky (2 each) and Dogo Argentino and Caucasian shepherd (1 each). There was no mean body weight difference (P = .569) between the fenoldopam (30.7 ± 12.5 kg) and placebo (32.5 ± 10.7 kg) groups.

3.2. Severity of heatstroke

The median rectal temperature at presentation to the VTH was 38.6°C (range 35.0–42.8°C). The median rectal temperature measured by the referring veterinarians (n = 11) before cooling was 42°C (range, 40.0–43.0°C).

When a previously established severity scoring system for dogs with heatstroke was applied,30 the average score was 39.3 ± 14.9, with no difference (P = .939) between the fenoldopam (39.2 ± 3.3) and placebo (39.5 ± 3.4) groups. The severity score at presentation was significantly (P = .024) higher in the nonsurvivors (46.5 ± 12.5) as compared with the survivors (35.5 ± 15.0).

Overall, 14/40 dogs (35%) died, with no significant (P = .507) mortality rate difference between the fenoldopam (6/20 dogs; 30%) and placebo (8/20; 40%) groups.

3.3. Arterial blood pressure

The overall means of systolic ABP (SAP), diastolic ABP (DAP) and mean ABP (MAP) at presentation were 130 ± 27, 75 ± 23, and 106 ± 23 mm Hg, respectively, with no treatment group differences (P = .601, P = .261, and P = .094, respectively). There were no differences between mean SAP, MAP, and DAP before and 4 hours after initiation of fenoldopam therapy (143 ± 26 versus 146 ± 35 mm Hg, P = .563; 106 ± 26 versus 116 ± 25 mm Hg, P = .220; and, 90 ± 27 versus 96 ± 29 mm Hg, P = .229, respectively). Systolic arterial hypotension (SAP < 100 mm Hg) was documented only on 2 occasions at presentation and after fenoldopam initiation, and MAP was >60 mm Hg in all dogs after initiation of fenoldopam therapy.

3.4. Acute kidney injury

Kidney function parameters are presented in Table 1. Based on IRIS guidelines, 22/40 (55%) of the dogs had AKI (Grade I, 1/22; Grade II, 5/22; Grade III, 11/22, and Grade IV, 5/22). Of these, 6 dogs developed overt AKI during hospitalization, whereas the rest already had presented with overt AKI. No significant difference was observed in the proportion of dogs that developed overt AKI during hospitalization between the fenoldopam and placebo groups (3 of each group, P = 1.00)

Table 1.

Kidney function parameters at presentation

| Fenoldopam (n = 20) | Placebo (n = 20) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Analyte | Median (range) | Median (Range) | P value |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.6 (0.5‐4.7) | 1.7 (0.7‐2.6) | .583 |

| Urine production (mL/kg/h) | 6 (0.4–28) | 4.3 (0.9–19) | .295 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/kg) | 0.92 (0.0–3.7) | 0.6 (0.0–3.1) | .201 |

| Sodium fractional excretion | 0.07 (0.01‐0.35) | 0.07 (0.01‐0.41) | .678 |

Serum creatinine was measured at presentation and urine production, sodium fractional excretion, and GFR were measured 4 hours from presentation.

The proportion of dogs with AKI was not significantly different (P = .204) between the fenoldopam (9/20; 45%) and the placebo (13/20; 65%) groups. The mortality rate of dogs diagnosed with AKI (11/22 dogs; 50%) was significantly (P = 0.046) higher than in those in which overt AKI was absent (3/18; 17%).

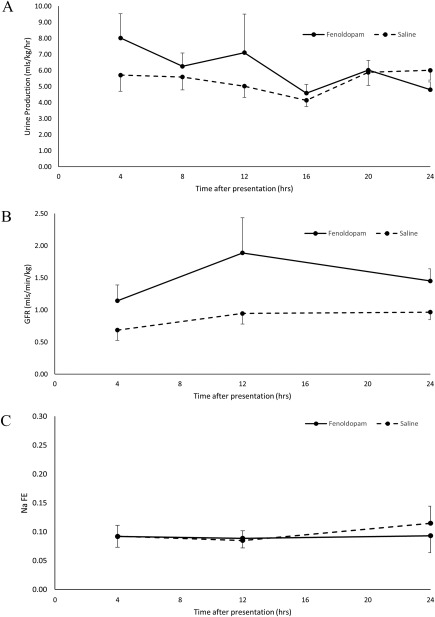

3.5. UP, GFR, and Na FE

Urine production was high in both the study and placebo groups (Figure 1). Oliguria (<1 mL/kg/h), based on UP once fluid deficits had been corrected (ie, 4 hours PP), was documented in only 2 dogs (1 of each group). A significant UP change occurred over time in the fenoldopam group (P = .044), but not in the placebo group (P = .683; Figure 1), but no significant UP differences were identified between groups at any time point during the first 24 hours PP (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A, urine production (mean ± SD) over time in dogs sustaining heatstroke, receiving fenoldopam (n = 20) or placebo (n = 20). B, glomerular filtration rate (mean ± SD) over time in dogs sustaining heatstroke, receiving fenoldopam (n = 20) or placebo (n = 20). C, sodium fractional excretion (mean ± SD) over time in dogs sustaining heatstroke, receiving fenoldopam (n = 20) or placebo (n =20)

No change in GFR was documented during the first 24 hours PP in the fenoldopam group (P = .155), but a significant change was noted in the placebo group (P = .019), with no significant GFR group differences at any time point (Figure 1).

The NaFE was high in both groups at presentation (Figure 1). There was no significant change NaFE over time, nor was there a difference, at any time point, between the treatment groups during first 24 hours PP (Figure 1).

4. DISCUSSION

We evaluated the effect of fenoldopam on sequential changes in GFR, UP, and NaFE during the first 24 hours of hospitalization in dogs with naturally occurring heatstroke‐induced AKI. Our results do not support the use of fenoldopam at a dosage of 0.1 µg/kg/min for managing heatstroke‐associated AKI.

Heatstroke often is complicated by AKI, which adversely affects mortality in dogs.6 Although, based on IRIS criteria, only 55% of the dogs in our study had AKI, previous studies using biomarkers with higher sensitivity compared with sCr concentration (which is a functional marker) or by histopathology of renal tissue in fatal cases of heatstroke in dogs both suggest that AKI is invariably present in these animals.25, 28

Fenoldopam, a DA‐1 receptor agonist, induces vasodilatation of the peripheral arteries. It has been studied as a substitute for dopamine, which failed to show beneficial effects in managing AKI in human patients.11, 13 In the renal proximal tubule, DA‐1 receptor activation results in vasodilatation of the renal arteries, promoting natriuresis and diuresis, increasing renal blood flow, and therefore, fenoldopam is considered part of the management of AKI in human patients.34, 35, 36, 37

Fenoldopam may increase UP by increasing both natriuresis and GFR.38 In our study, UP was high at presentation (Figure 1), with no significant difference between the study and the placebo groups, suggesting that the effect of fenoldopam on UP was mild at best. This lack of apparent group difference might have resulted from relatively aggressive IV fluid therapy and the use of mannitol, which were administered early PP. Many dogs with AKI, and typically those with heatstroke, which invariably sustain kidney damage,28 are not oliguric when initially presented,3 a finding that appears to be associated with a better prognosis compared to oliguric AKI.1, 9, 39 Therefore, the current treatment protocol in our hospital includes aggressive IV crystalloid therapy and mannitol to prevent oliguria or anuria, resulting in relatively high UP. This high, albeit variable, UP among the dogs might have negated the differences between the fenoldopam and placebo groups.

The relatively low GFR documented here in dogs sustaining heatstroke further exemplifies the insensitivity of sCr as a kidney function marker, and further supports previous results, indicating that kidney injury is present dogs with heatstroke, even if not reflected by increased sCr at presentation.28 Because dogs sustaining heatstroke usually are presented for veterinary care relatively promptly after the acute and severe clinical signs of this syndrome have begun,6 sCr concentration at presentation does not reflect the severity of kidney injury, because a steady state has not been reached. Glomerular filtration rate in our study increased only mildly and insignificantly after fenoldopam administration, and no significant GFR differences were noted between treatment groups. Information regarding the effect of fenoldopam on GFR in the veterinary literature is limited and inconsistent. In cats, GFR initially decreased, but had increased by 6 hours after initiation of fenoldopam therapy.40 In healthy dogs, fenoldopam has led to a 0.78 mL/min/kg increase in the GFR, as measured by iohexol clearance, but the increase was inconsistent among the study dogs, with some showing only minimal to no GFR change. In humans, fenoldopam administered to healthy subjects at dosages ranging from 0.03 to 0.3 µg/kg/min led to significant GFR changes.41 The inconsistency of the present and previous results might be related to differences between the species studied, the dosage used (0.1‐0.8 µg/kg/min),20, 38, 41 and the health status of the patients (ie, healthy animals versus those with AKI). Nonetheless, the currently used fenoldopam dosage did not increase GFR in a clinically relevant manner.

In our study, NaFE also was not significantly different between groups. In a previous study of healthy dogs, NaFE increased significantly after fenoldopam administration,38 but, the increase was inconsistent and relatively mild (0.016). Possibly, the higher fenoldopam dosages used in that previous study, as well as the higher variability that exists among dogs with kidney injury, render the changes in NaFE insignificant. In our study, the relatively high NaFE noted 4 hours PP reflects the extensive disruption of tubular resorptive function in the injured kidneys, consistent with a previous study.1 Fractional sodium excretion might be influenced by the sodium‐containing fluids administered, which can increase NaFE, possibly negating any treatment group difference.

Fenoldopam is used in human patients to manage hypertension and prevent and manage AKI.42, 43, 44 In our study, fenoldopam administration did not decrease the extent of azotemia or the occurrence of kidney injury (based on IRIS guidelines29) compared to placebo, in agreement with a previous study using fenoldopam (0.05 µg/kg/min IV by CRI) in human patients.20 Consistent with previous studies, presence of overt AKI was significantly associated with death.6 The lack of efficacy of vasodilators in clinical trials of AKI may result from their relatively late administration in the disease course. We therefore have elected to study the effect of fenoldopam in a naturally occurring model, where dogs are mostly presented relatively soon after the insult. Nonetheless, in most dogs (73%) the diagnosis of AKI was already made by presentation. Therefore, the effect of fenoldopam on the progression of kidney injury cannot be assessed in these animals.

Fenoldopam, a dompaminergic agonist, may promote vasodilatation and hypotension.42, 43 To prevent hypotension, fenoldopam administration was initiated 4 hours PP, after hydration status and hypovolemia had been corrected. Hypotension episodes after fenoldopam initiation were uncommon, and with aggressive IV fluid administration, it is quite safe at the currently administered dosage, in agreement with a previous pharmacokinetic study of fenoldopam in dogs,34 and others, in which fenoldopam administration was uncommonly (7%) associated with hypotension in dogs.23, 38

In a previous study, a scoring system for dogs sustaining heatstroke at presentation for care was developed.30 Using that scoring system in our cohort showed that the median scores were similar in both treatment groups, suggesting that the 2 groups were comparable at presentation, but was significantly higher in the nonsurvivors. This scoring system originally was developed and tested on the same cohort, which was a limitation of that study.30 The present cohort is relatively small for the independent validation of this scoring system. Nevertheless, the score was significantly higher in the nonsurvivors compared with the survivors, potentially supporting its validity, but this suggestion warrants further evaluation in larger cohorts.

Our study had several limitations. First, the limited cohort size might have rendered our study underpowered, and thereby prone to type‐II error. For the occurrence of AKI documented in our study to become statistically significant, a substantially higher number of dogs should ideally have been included (assuming an alpha of 5% and power of 80%). Therefore, larger scale studies are warranted to evaluate the effect of fenoldopam on the occurrence of AKI in dogs at risk before concluding that fenoldopam does not decrease that risk. Second, 45% of the dogs did not fulfill the IRIS criteria for AKI, limiting our conclusion as to the potential beneficial effect of fenoldopam, and therefore it should be tested in dogs with overt AKI. Third, the fenoldopam dosage used in our study was relatively low (although comparable to that used in previous studies in humans). When our study protocol was originally designed, veterinary information regarding the effect of fenoldopam on kidney function parameters was unavailable, and the dosage used here was based on the human medicial literature. Since then, fenoldopam has been evaluated in veterinary patients, using higher dosages (0.5–0.8 µg/kg/min). The relatively low fenoldopam dosage used in our study might have resulted in a lack of detectable beneficial effects of the drug. Additional studies using higher fenoldopam dosages in dogs are warranted.

In conclusion, administration of fenoldopam at a dosage of 0.1 μg/kg/min IV by CRI in dogs with heatstroke was not associated with any observable adverse effects. However, it had no beneficial effects on UP, GFR, NaFE, or on the occurrence and severity of AKI.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the content of this article.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no IACUC or other approval was needed.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

Segev G, Bruchim Y, Berl N, Cohen A, Aroch I. Effects of fenoldopam on kidney function parameters and its therapeutic efficacy in the management of acute kidney injury in dogs with heatstroke. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32:1109–1115. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15081

Funding information European College of Veterinary Internal Medicine

The patients were treated at the Hebrew University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rishon Lezion, Israel.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brown N, Segev G, Francey T, Kass P, Cowgill LD. Glomerular filtration rate, urine production, and fractional clearance of electrolytes in acute kidney injury in dogs and their association with survival. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Behrend EN, Grauer GF, Mani I, Groman RP, Salman MD, Greco DS. Hospital‐acquired acute renal failure in dogs: 29 cases (1983–1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996;208:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vaden SL, Levine J, Breitschwerdt EB. A retrospective case‐control of acute renal failure in 99 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 1997;11:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adin CA, Cowgill LD. Treatment and outcome of dogs with leptospirosis: 36 cases (1990–1998). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;216:371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown SA, Barsanti JA, Crowell WA. Gentamicin‐associated acute renal failure in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:686–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruchim Y, Klement E, Saragusty J, Finkeilstein E, Kass P, Aroch I. Heat stroke in dogs: a retrospective study of 54 cases (1999–2004) and analysis of risk factors for death. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eubig PA, Brady MS, Gwaltney‐Brant SM, Khan SA, Mazzaferro EM, Morrow CM. Acute renal failure in dogs after the ingestion of grapes or raisins: a retrospective evaluation of 43 dogs (1992–2002). J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:663–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Langston CE. Acute renal failure caused by lily ingestion in six cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;220:49–52, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Segev G, Kass PH, Francey T, Cowgill LD. A novel clinical scoring system for outcome prediction in dogs with acute kidney injury managed by hemodialysis. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Langston CE. Acute uremia In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders WB; 2010:1955–2115. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bellomo R, Chapman M, Finfer S, Hickling K, Myburgh J. Low‐dose dopamine in patients with early renal dysfunction: a placebo‐controlled randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2139–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Friedrich JO, Adhikari N, Herridge MS, Beyene J. Meta‐analysis: low‐dose dopamine increases urine output but does not prevent renal dysfunction or death. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:510–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kellum JA, M Decker J. Use of dopamine in acute renal failure: a meta‐analysis. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1526–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marik PE. Low‐dose dopamine: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murphy MB, Murray C, Shorten GD. Fenoldopam: a selective peripheral dopamine‐receptor agonist for the treatment of severe hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1548–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Halpenny M, Rushe C, Breen P, Cunningham AJ, Boucher‐Hayes D, Shorten GD. The effects of fenoldopam on renal function in patients undergoing elective aortic surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2002;19:32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moffett BS, Mott AR, Nelson DP, Goldstein SL, Jefferies JL. Renal effects of fenoldopam in critically ill pediatric patients: a retrospective review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(4):403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stone GW, McCullough PA, Tumlin JA, et al. Fenoldopam mesylate for the prevention of contrast‐induced nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:2284–2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morelli A, Ricci Z, Bellomo R, et al. Prophylactic fenoldopam for renal protection in sepsis: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled pilot trial. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2451–2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tumlin JA, Finkel KW, Murray PT, Samuels J, Cotsonis G, Shaw AD. Fenoldopam mesylate in early acute tubular necrosis: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Landoni G, Biondi‐Zoccai GG, Marino G, et al. Fenoldopam reduces the need for renal replacement therapy and in‐hospital death in cardiovascular surgery: a meta‐analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Venkataraman R. Can we prevent acute kidney injury? Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S166–S171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nielsen LK, Bracker K, Price LL. Administration of fenoldopam in critically ill small animal patients with acute kidney injury: 28 dogs and 34 cats (2008–2012). J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2015;25:396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dematte JE, O'Mara K, Buescher J, et al. Near‐fatal heat stroke during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bruchim Y, Loeb E, Saragusty J, Aroch I. Pathological findings in dogs with fatal heatstroke. J Comp Pathol. 2009;140:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aroch I, Segev G, Loeb E, Bruchim Y. Peripheral nucleated red blood cells as a prognostic indicator in heatstroke in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;23:544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin YF, Wang JY, Chou TC, Lin SH. Vasoactive mediators and renal haemodynamics in exertional heat stroke complicated by acute renal failure. QJM. 2003;96:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Segev G, Daminet S, Meyer E, et al. Characterization of kidney damage using several renal biomarkers in dogs with naturally occurring heatstroke. Vet J. 2015;206:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.IRIS. International Renal Interest Society Web site. http://www.iris-kidney.com/. Accessed February 7, 2018.

- 30. Segev G, Aroch I, Savoray M, Kass PH, Bruchim Y. A novel severity scoring system for dogs with heatstroke. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2015;25:240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Finco DR, Tabaru H, Brown SA, Barsanti JA. Endogenous creatinine clearance measurement of glomerular filtration rate in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54:1575–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bovee KC, Joyce T. Clinical evaluation of glomerular function: 24‐hour creatinine clearance in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1979;174:488–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Finco DR, Coulter DB, Barsanti JA. Simple, accurate method for clinical estimation of glomerular filtration rate in the dog. Am J Vet Res. 1981;42:1874–1877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bloom CA, Labato MA, Hazarika S, Court MH. Preliminary pharmacokinetics and cardiovascular effects of fenoldopam continuous rate infusion in six healthy dogs. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Singer I, Epstein M. Potential of dopamine A‐1 agonists in the management of acute renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:743–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goldberg LI. Dopamine and new dopamine analogs: receptors and clinical applications. J Clin Anesth. 1988;1:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grund E, Muller‐Ruchholtz ER, Hauer F, Lapp ER. Effects of dopamine on total peripheral resistance and integrated systemic venous blood volume in dogs. Basic Res Cardiol. 1980;75:623–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kelly KL, Drobatz KJ, Foster JD. Effect of fenoldopam continuous infusion on glomerular filtration rate and fractional excretion of sodium in healthy dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30:1655–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smithies MN, Cameron JS. Can we predict outcome in acute renal failure? Nephron. 1989;51:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simmons JP, Wohl JS, Schwartz DD, Edward HG, Wright JC. Diuretic effects of fenoldopam in healthy cats. J Vet Emerg Crit. 2006;16:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mathur VS, Swan SK, Lambrecht LJ, et al. The effects of fenoldopam, a selective dopamine receptor agonist, on systemic and renal hemodynamics in normotensive subjects. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1832–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haas CE, LeBlanc JM. Acute postoperative hypertension: a review of therapeutic options. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:1661–1673. quiz 1674‐1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tuncel M, Ram VC. Hypertensive emergencies. Etiology and management. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003;3:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Caimmi PP, Pagani L, Micalizzi E, et al. Fenoldopam for renal protection in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Anesth. 2003;17:491–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]