Abstract

Interaction of signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) expressed on the surface of macrophages with its ligand CD47 expressed on target cells negatively regulates phagocytosis of the latter cells by the former. We recently showed that blocking Abs to mouse SIRPα enhanced both the Ab‐dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) activity of mouse macrophages for Burkitt's lymphoma Raji cells opsonized with an Ab to CD20 (rituximab) in vitro as well as the inhibitory effect of rituximab on the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells in nonobese diabetic (NOD)/SCID mice. However, the effects of blocking Abs to human SIRPα in preclinical cancer models have remained unclear given that such Abs have failed to interact with endogenous SIRPα expressed on macrophages of immunodeficient mice. With the use of Rag2−/−γc −/− mice harboring a transgene for human SIRPα under the control of human regulatory elements (hSIRPα‐DKO mice), we here show that a blocking Ab to human SIRPα significantly enhanced the ADCP activity of macrophages derived from these mice for human cancer cells. The anti‐human SIRPα Ab also markedly enhanced the inhibitory effect of rituximab on the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells in hSIRPα‐DKO mice. Our results thus suggest that the combination of Abs to human SIRPα with therapeutic Abs specific for tumor antigens warrants further investigation for potential application to cancer immunotherapy. In addition, humanized mice, such as hSIRPα‐DKO mice, should prove useful for validation of the antitumor effects of checkpoint inhibitors before testing in clinical trials.

Keywords: antibody, CD47, macrophage, phagocytosis, signal regulatory protein α

1. INTRODUCTION

The therapeutic effects of Abs that target immune‐checkpoint molecules such as programmed cell death‐1 (PD‐1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4) on T cells have been described for a variety of cancers.1, 2 However, validation of the efficacy of Abs to human PD‐1 or CTLA‐4 before clinical testing in patients is difficult because immunodeficient mice lacking T cells, B cells and natural killer (NK) cells are often used for implantation of human tumor cells in preclinical models.3, 4

Signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) is a transmembrane protein, the extracellular region of which comprises 3 Ig‐like domains and the cytoplasmic region contains immunoreceptor tyrosine‐based inhibition motifs.5, 6 SIRPα is especially abundant in myeloid cells such as macrophages, whereas it is barely expressed in T cells, B cells, NK cells and NK T cells.7, 8, 9, 10 The extracellular region of SIRPα interacts with the ligand CD47, which is also a member of the Ig superfamily of proteins.5, 6, 11 In contrast to the relatively restricted distribution of SIRPα, CD47 is expressed in most normal cell types as well as in cancer cells.11 The interaction of CD47 on the surface of red blood cells with SIRPα on macrophages inhibits phagocytosis of the former cells by the latter.5, 11, 12, 13 The CD47‐SIRPα interaction has also been demonstrated to function as an inhibitory signal for phagocytosis of cancer cells by macrophages.14, 15, 16, 17 It was also demonstrated that human CD47 can nicely bind to SIRPα from nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice, whereas it minimally interacts with SIRPα from either BALB/c, 129 or C57BL/6 mice.18, 19, 20, 21 Such a difference between mouse SIRPα subtypes for their binding abilities to human CD47 is likely attributable to amino acid variations in the N‐terminal Ig‐V domain of SIRPα.18, 20 Indeed, we have recently shown that Abs to mouse SIRPα that inhibit the interaction of CD47 with SIRPα enhanced the suppressive effect of the CD20‐specific mAb rituximab on the growth of tumors formed by Burkitt's lymphoma Raji cells in NOD/SCID mice,22 with this effect appearing to be mediated by blockade of CD47 (on Raji cells)‐SIRPα (on NOD/SCID macrophages) signaling that negatively regulates such phagocytosis. SIRPα is, thus, a promising target for cancer immunotherapy. The potential therapeutic effect of Abs to human SIRPα in preclinical models has remained unclear, however, because such Abs have failed to react with endogenous SIRPα expressed on macrophages in non‐NOD background immunodeficient mice injected with human cancer cells.

To address this issue, we have now taken advantage of immunodeficient Rag2−/−γc −/− double‐knockout (DKO) mice that harbor a transgene for human SIRPα under the control of human regulatory elements (hSIRPα‐DKO mice).23 Injection of blocking Abs to human SIRPα into hSIRPα‐DKO mice would be expected to prevent the interaction of CD47 on implanted human cancer cells with human SIRPα on mouse phagocytes and thereby to enhance Ab‐dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP). We therefore examined the effects of such Abs both on ADCP activity of bone marrow‐derived macrophages (BMDM) from hSIRPα‐DKO mice (129/BALB/c mixed background)23 as well as on the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells in these animals.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Abs and reagents

A rat mAb to mouse SIRPα (clone MY‐1) and mouse mAbs to human SIRPα (SE12C3 [mouse IgG1] and 040 [mouse IgG1]) were generated and purified as described previously.7, 22, 24 Rabbit pAbs to SIRPα (ab53721), which were generated against the cytoplasmic region of human SIRPα, were from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Rituximab (mAb to human CD20) and trastuzumab (mAb to HER2) were obtained from Chugai Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan). A biotin‐conjugated mAb to mouse SIRPα (clone P84), a phycoerythrin (PE)‐conjugated mAb to mouse F4/80 (clone BM8) and a rat mAb to mouse CD16/32 (clone 93) were obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). An FITC‐conjugated mAb to mouse CD4 (clone GK1.5), a peridinin chlorophyll protein complex‐conjugated mAb to mouse CD8α (clone 53‐6.7), an allophycocyanin (APC)‐conjugated mAb to mouse CD11c (clone HL3) and a PE‐conjugated mAb to mouse Ly6G (clone 1A8) were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). APC‐conjugated streptavidin, a brilliant violet 421‐conjugated mAb to mouse or human CD11b (clone M1/70), a pacific blue‐conjugated mAb to mouse or human CD11b (clone M1/70), an APC‐ and cyanine7 (Cy7)‐conjugated mAb to mouse or human CD45R/B220 (clone RA3‐6B2), a brilliant violet 510‐conjugated mAb to mouse CD45 (clone 30‐F11), a PE‐conjugated and Cy7‐conjugated mAb to human SIRPα/β (clone SE5A5), an FITC‐conjugated mAb to mouse F4/80 (clone BM8), a biotin‐conjugated mAb to mouse F4/80 (clone BM8), PE‐conjugated and Cy7‐conjugated streptavidin, a PE‐conjugated and Cy7‐conjugated mouse IgG1κ isotype control (clone MOPC‐21) and Zombie Aqua were obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Alexa Fluor 488‐conjugated goat polyclonal Abs (pAbs) to rabbit IgG and carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). HRP‐conjugated goat pAbs to the Fcγ fragment of human IgG was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). Propidium iodide (PI) was from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cy3‐conjugated goat pAbs to mouse or rat IgG as well as normal rat and mouse IgG were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories.

2.2. Animals

129S4‐Rag2 tm1.1Flv Il2rg tm1.1FlvTg(SIRPA)1Flv/J (hSIRPα‐DKO) mice and 129S4‐Rag2 tm1.1Flv Il2rg tm1.1Flv/J (DKO) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and were maintained at the Institute for Experimental Animals at Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine under specific pathogen‐free conditions. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed according to Kobe University Animal Experimentation Regulations.

2.3. Cell preparation and flow cytometry

For isolation of splenocytes, mouse spleen was ground gently with autoclaved frosted‐glass slides in PBS, fibrous material was removed by filtration through a 70‐μm cell strainer, and red blood cells in the filtrate were lysed with BD Pharm Lyse (BD Biosciences). The remaining cells were washed twice with PBS and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis. The cells were first incubated with a mAb specific for mouse CD16/32 to prevent nonspecific binding of labeled mAbs to the Fcγ receptor and were then labeled with specific mAbs. Labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with the use of a FACSVerse instrument (BD Biosciences), and all data were analyzed with FlowJo software 9.9.3 (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). For preparation of BMDM, bone marrow cells were isolated from the femur and tibia of mice with the use of a syringe fitted with a 27‐gauge needle as described previously,22 with slight modifications. The cells (1 × 106/mL) were seeded on culture plates in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with recombinant murine macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (10 ng/mL; Tonbo Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) and 10% FBS to obtain BMDM. The expression of CD11b, F4/80 and SIRPα on BMDM was similarly determined by flow cytometry.

For determination of the expression of SIRPα on human cancer cell lines, the cells were treated with Human TruStain FcX (BioLegend), washed with PBS, and then stained with a PE‐conjugated and Cy7‐conjugated mAb to human CD172a/b (SIRPα/β) or a PE‐conjugated and Cy7‐conjugated isotype control IgG. Stained cells were subjected to flow cytometry and data were analyzed with FlowJo software.

2.4. Cell culture

Raji and BT474 cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). HEK293A cells were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Raji and BT474 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Wako, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS. HEK293A cells were cultured in DMEM (Wako) supplemented with 10% FBS. CHO cells stably expressing an active form of H‐Ras (CHO‐Ras cells) were kindly provided by S. Shirahata (Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan), whereas CHO‐Ras cells stably expressing human or mouse SIRPα were kindly provided by N. Honma (Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Tokyo, Japan).25, 26 CHO‐Ras cells and their derivatives were cultured in α‐modified minimum essential medium (Sigma‐Aldrich) supplemented with 2 mmol/L l‐glutamine, 10 mmol/L HEPES‐NaOH (pH 7.4) and 10% FBS.

2.5. Plasmids and transfection

A plasmid encoding human SIRPα variant 2 (SIRPαv2) was kindly provided by N. Honma. For construction of expression vectors encoding human SIRPαv2 mutants lacking the first Ig‐like domain (ΔV) or both the first and second Ig‐like domains (ΔVC1), the mutated cDNA were generated by PCR‐ligation mutagenesis with full‐length human SIRPαv2 cDNA as the template, as described previously.27 The sequences of all PCR products were verified by sequencing with an ABI3100 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). HEK293A cells were transfected with expression vectors with the use of Lipofectamine2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.6. Protein binding assay

The extracellular domain of human CD47 (amino acids 1‐161) fused to human Fc was generated as described.25 The human CD47‐Fc fusion protein produced by cells cultured in serum‐free α‐modified minimum essential medium was purified from culture supernatants by chromatography with a column of protein A‐Sepharose 4FF (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). A protein‐based binding assay was performed as previously described,26 with slight modifications. In brief, confluent CHO‐Ras cells expressing human SIRPα (CHO‐Ras‐hSIRPα cells) or parental CHO‐Ras cells in 96‐well plates were washed twice with serum‐free culture medium and then incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C with human CD47‐Fc (1 μg/mL) in the presence of the anti‐human SIRPα Abs SE12C3 (50 μg/mL) or 040 (50 μg/mL) or of normal mouse IgG (50 μg/mL) in α‐modified minimum essential medium. The cells were then washed 3 times with ice‐cold PBS before incubation for 30 minutes at 4°C with HRP‐conjugated goat pAbs to the Fcγ fragment of human IgG at a 1:2000 dilution in PBS containing 1% BSA. After 3 washes with PBS, the cells were assayed for binding of human CD47‐Fc by measurement of peroxidase activity with the use of an ELISA POD Substrate TMB Kit (Nacalai Tesque). Absorbance at 490 nm (A 490) was measured for each well with a microplate reader (2030 ARVO X4; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

For determination of the binding of human CD47‐Fc to BMDM, confluent BMDM in 96‐well plates were treated with mAbs to CD16/32, and incubated in the presence of increasing concentrations of either human Fc or CD47‐Fc for 30 minutes at 4°C. After 3 washes with PBS, the cells were then further incubated with HRP‐conjugated goat pAbs to the Fcγ fragment of human IgG. The cells were assayed for binding of human Fc or CD47‐Fc as described above.

2.7. Immunostaining

Cells were fixed for 10 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde, incubated for 30 minutes with buffer G (PBS containing 5% goat serum and 0.1% Triton X‐100), and stained with primary Abs in the same buffer. Immune complexes were detected with dye‐labeled secondary Abs in buffer G. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. The cells were then examined with a fluorescence microscope (BX61; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and fluorescence images were captured with a cooled digital color camera (DP70, Olympus).

2.8. Tumor cell engraftment and treatment

Raji cells (3 × 106 in 50 μL of PBS) were mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and injected s.c. into the flank of female or male hSIRPα‐DKO mice at 8‐12 weeks of age. The mice were injected i.p. either with normal mouse IgG (200 μg), SE12C3 (200 μg) or 040 (200 μg), each with or without rituximab (150 μg), twice a week beginning after tumor volume had achieved an average of 100 mm3. Tumors were measured with digital calipers, and tumor volume was calculated as a × b 2/2, where a is the largest diameter and b the smallest diameter.

2.9. Blood biochemical analysis

Female or male hSIRPα‐DKO mice at 8‐12 weeks of age were injected i.p. with PBS or with normal mouse IgG or SE12C3 (each at 200 μg) 3 times a week. On day 14, blood biochemical parameters were analyzed with the use of an Auto Analyzer 7070 (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

2.10. Ab‐dependent cellular phagocytosis assay

Ab‐dependent cellular phagocytosis assays were performed as described previously.15 In brief, BMDM were plated at a density of 1 × 105 per well in 6‐well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Target cells (4 × 105) were labeled with CFSE, added to the BMDM (effector cells), and incubated for 4 hours in the presence of rituximab (0.025 μg/mL), trastuzumab (0.5 μg/mL), SE12C3 (2.5 μg/mL), 040 (2.5 μg/mL) or normal mouse IgG (2.5 μg/mL). Cells were then harvested, stained for F4/80 as well as with PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentage phagocytosis by BMDM was calculated as: 100 × F4/80+CFSE+PI− cells/(F4/80+CFSE+PI− cells + F4/80+CFSE−PI− cells).

2.11. Depletion of macrophages in vivo

Depletion of macrophages in female or male hSIRPα‐DKO mice at 8‐12 weeks of age was performed as described previously,22 with minor modifications. In brief, mice were injected i.v. with 200 μL of either clodronate liposomes or PBS liposomes (Liposoma B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands) every 3 days beginning 10 days after tumor cell injection. The effectiveness of macrophage depletion was determined by flow cytometric analysis of CD45+F4/80+CD11b+ cells among splenocytes of the treated animals.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM and were analyzed by 1‐way or 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test, or by the log‐rank test. A P‐value of < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed with the use of GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. hSIRPα‐DKO mice manifest a pattern of human SIRPα expression similar to that of endogenous mouse SIRPα in hematopoietic cells

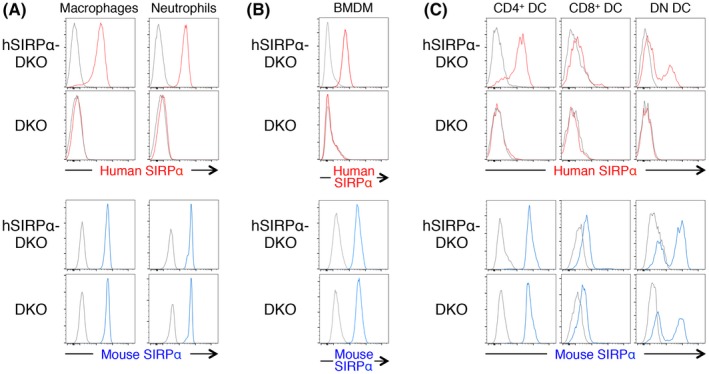

Mouse SIRPα is expressed at a high level in macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells (DC), but at a minimal level in T, B and NK cells.5, 10 We therefore first examined the expression pattern of human SIRPα on the surface of various hematopoietic cell types from the spleen of hSIRPα‐DKO mice and compared it with that of endogenous mouse SIRPα. Expression of human SIRPα was prominent on both CD11b+CD11c−B220−F4/80+ macrophages and CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils of hSIRPα‐DKO mice, whereas no such expression was detected on these cells of control DKO mice (Figure 1A). Moreover, the expression level of mouse SIRPα in these splenocytes was similar for hSIRPα‐DKO and DKO mice (Figure 1A). Consistent with these results, BMDM from hSIRPα‐DKO mice, but not DKO mice, expressed exogenous human SIRPα on the cell surface, whereas the expression level of endogenous mouse SIRPα on these cells was comparable between 2 genotypes (Figure 1B). Mouse CD11c+ conventional DC (cDC) are classified into 3 subpopulations: CD4+CD8− cDC (CD4+ cDC), CD4−CD8+ cDC (CD8+ cDC) and CD4−CD8− cDC (DN cDC).10 Mouse CD4+ cDC and DN cDC express SIRPα at a high level, whereas CD8+ cDC express the protein at a relatively low level. This expression pattern was also apparent for human SIRPα in cDC of hSIRPα‐DKO mice (Figure 1C). Again, the expression level of mouse SIRPα in each cDC subpopulation was similar for hSIRPα‐DKO and DKO mice (Figure 1C). These results thus showed that: (i) human SIRPα is expressed predominantly on macrophages, neutrophils and DC of hSIRPα‐DKO mice; (ii) the expression pattern of human SIRPα on these myelogenous hematopoietic cells is similar to that of endogenous mouse SIRPα; and (iii) the expression of human SIRPα does not impair the expression of endogenous mouse SIRPα in hSIRPα‐DKO mice.

Figure 1.

Expression of human and mouse SIRPα on macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells (DC) of hSIRPα‐DKO mice. A‐C, Splenocytes isolated from adult hSIRPα‐DKO or DKO mice were stained for CD11b, CD11c, B220 and F4/80 (A, left panels), for CD11b and Ly6G (A, right panels), and for CD11c, B220, CD4 and CD8α (C) for isolation of macrophages, neutrophils and cDC subpopulations. Bone marrow‐derived macrophages (BMDM) from hSIRPα‐DKO or DKO mice were stained for CD11b and F4/80 (B). The cells were also stained for human or mouse SIRPα and with Zombie Aqua for detection of dead cells before analysis by flow cytometry. All data are representative of 3 separate experiments

3.2. Anti‐human SIRPα Abs promote Ab‐dependent cellular phagocytosis by macrophages from hSIRPα‐DKO mice

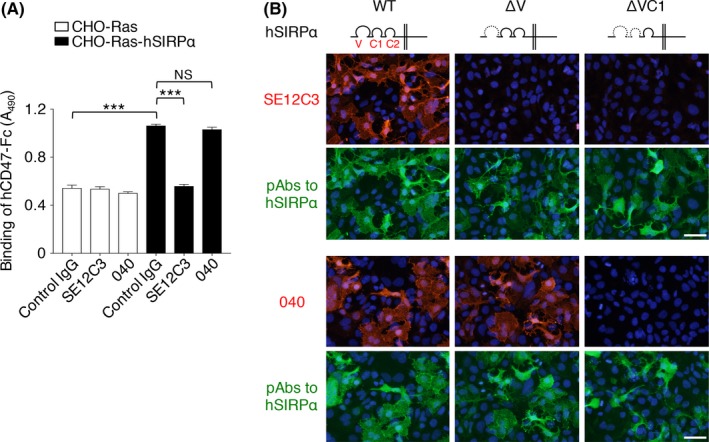

To examine the potential antitumor effects of Abs to human SIRPα, we characterized 2 different such mAbs, SE12C37 and 040.22 SE12C3 prevented the binding of a recombinant human CD47‐Fc fusion protein to CHO‐Ras cells expressing human SIRPα, whereas 040 had no such effect (Figure 2A). Among the 3 Ig domains (V, C1 and C2) in the extracellular region of SIRPα (Figure 2B), CD47 is thought to bind to the NH2‐terminal V domain.5, 11 Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that SE12C3 stained HEK293A cells expressing WT human SIRPα but not those expressing a mutant [SIRPα(ΔV)] lacking the V domain (Figure 2B). In contrast, the 040 mAb stained both WT and ΔV mutant forms of SIRPα, whereas it failed to stain a mutant [SIRPα(ΔVC1)] lacking both the V and C1 domains (Figure 2B). These results suggested that SE12C3 binds to the NH2‐terminal Ig‐V‐like domain of SIRPα and thereby blocks the interaction with CD47, as previously described for this mAb,7 whereas 040 likely reacts with the Ig‐C1‐like domain of SIRPα and has little effect on the CD47‐SIRPα interaction. Neither SE12C3 nor 040 showed substantial cross‐reactivity with mouse SIRPα expressed in cultured cells (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Effect of mAbs to human SIRPα on the human CD47‐SIRPα interaction in vitro. A, Binding of human CD47‐Fc (hCD47‐Fc) to CHO‐Ras cells stably expressing human SIRPα (CHO‐Ras‐hSIRPα cells) or to CHO‐Ras cells was determined in the presence of SE12C3 or 040 mAbs to human SIRPα or of control IgG. Data are means ± SEM of triplicate determinations and are representative of 3 separate experiments. ***P < .001; NS, not significant (1‐way ANOVA and Tukey's test). B, HEK293A cells were transfected for 24 hours with an expression vector for WT or the indicated mutant forms of human SIRPαv2, fixed, and subjected to immunofluorescence staining with mAbs (SE12C3 or 040) or pAbs to human SIRPα. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Images are representative of 3 separate experiments. Scale bars, 50 μm

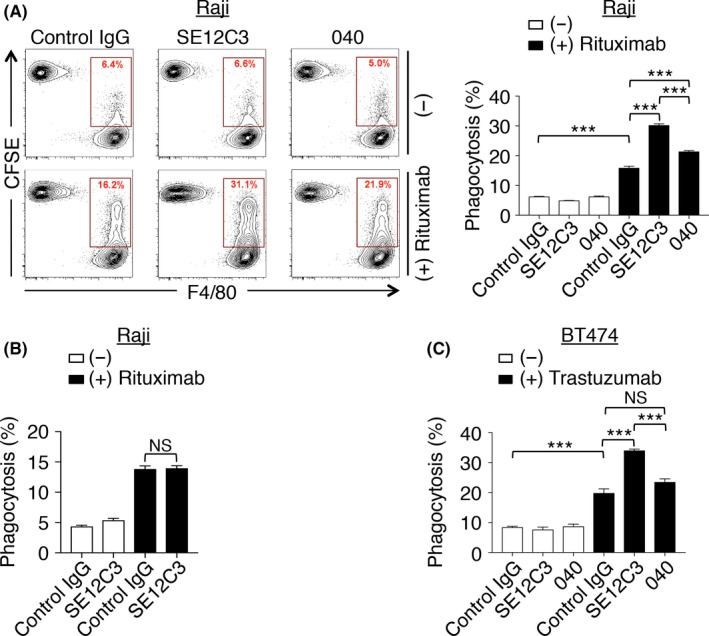

We next examined the effect of these 2 Abs to human SIRPα on ADCP activity of macrophages using 2 human tumor cell lines, Raji cells and breast cancer BT474 cells, in which the expression of human SIRPα was minimal (Figure S2). SE12C3 markedly enhanced rituximab‐dependent phagocytosis of CFSE‐labeled Raji cells by BMDM from hSIRPα‐DKO mice, whereas it had no effect on that by those from DKO mice (Figure 3B). These results thus suggested that this effect of SE12C3 is dependent on the expression of human SIRPα on macrophages from hSIRPα‐DKO mice. The mAb 040 also enhanced rituximab‐induced phagocytosis of Raji cells by BMDM from hSIRPα‐DKO mice compared with control IgG, albeit to a lesser extent than did SE12C3 (Figure 3A). Similarly, SE12C3 significantly enhanced trastuzumab‐dependent phagocytosis of human breast cancer BT474 cells by BMDM from hSIRPα‐DKO mice, whereas 040 had a much less pronounced effect in this assay (Figure 3C). It was demonstrated that human CD47 minimally binds to SIRPα from either BALB/c, 129 or C57BL/6 mice.18, 19, 20, 21 In contrast, human CD47 can strongly bind to SIRPα from NOD mice.18, 19, 20 Indeed, the specific binding of a recombinant human CD47‐Fc fusion protein to BMDM from DKO mice (129/BALB/c mixed background) was minimal and only observed at the high concentration of the recombinant protein (Figure S3, right panel). In contrast, the human CD47‐Fc fusion protein significantly bound to BMDM from hSIRPα‐DKO mice (Figure S3, left panel), suggesting that human CD47 (on cancer cells) preferentially binds to human SIRPα, rather than endogenous mouse SIRPα, on BMDM from hSIRPα‐DKO mice. Moreover, it is unlikely that human CD47 on Raji and BT474 cells transduces the inhibitory signals to macrophages through endogenous mouse SIRPα on macrophages of hSIRPα‐DKO mice. Together, these results suggested that blockade by SE12C3 of the inhibitory signal generated by the interaction of CD47 (on cancer cells) with human SIRPα (on BMDMs) contributes to the enhancement of ADCP.

Figure 3.

Enhancement by Abs to human SIRPα of the phagocytosis of Ab‐opsonized tumor cells by macrophages from hSIRPα‐DKO mice. A,B, Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)‐labeled Raji cells were incubated for 4 hours with bone marrow‐derived macrophages (BMDM) from hSIRPα‐DKO (A) or DKO (B) mice in the presence of the indicated Abs, after which cells were harvested, stained with a biotin‐conjugated mAb to F4/80 and APC‐conjugated streptavidin as well as with propidium iodide (PI) for analysis by flow cytometry. The relative number of CFSE +F4/80+ BMDM (BMDM that had phagocytosed CFSE‐labeled Raji cells) is expressed as a percentage of all viable F4/80+ cells in the representative plots and the bar charts. C, CFSE‐labeled BT474 cells were incubated for 4 hours with BMDM from hSIRPα‐DKO mice in the presence of the indicated Abs. The percentage of CFSE +F4/80+ BMDM among viable F4/80+ cells was then determined. All data are representative of 3 separate experiments, with those in the bar charts being means ± SEM of triplicate determinations from 1 experiment. ***P < .001; NS, not significant (1‐way ANOVA and Tukey's test)

3.3. Enhancement by SE12C3 of the inhibitory effect of rituximab on the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells

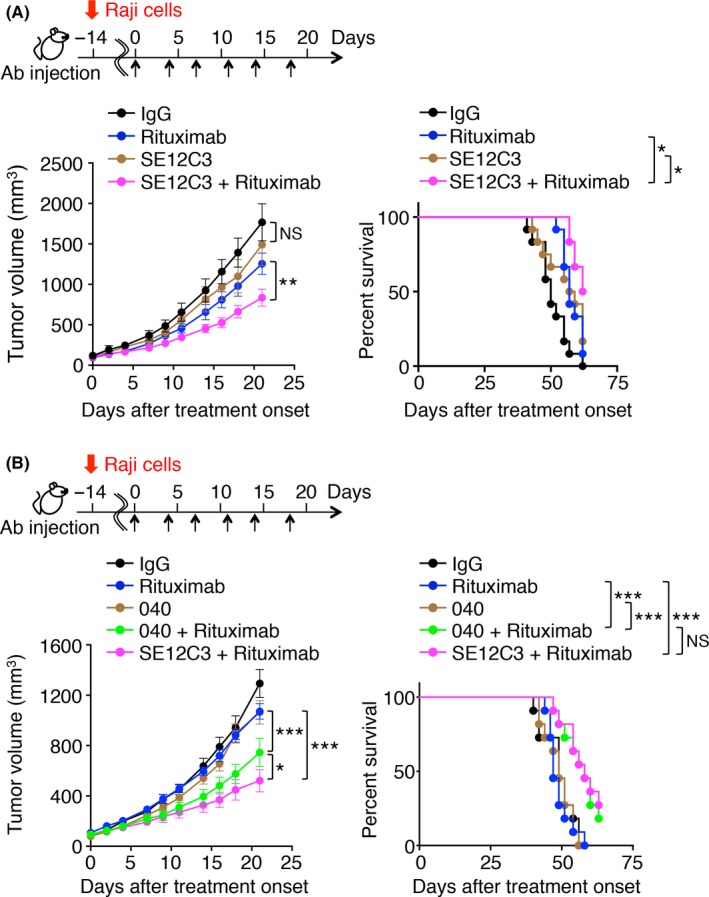

We next investigated whether SE12C3 might enhance the suppression by rituximab of tumor growth in hSIRPα‐DKO mice. Raji cells were transplanted s.c. into hSIRPα‐DKO mice at 8‐12 weeks of age. The animals were treated i.p. twice a week with rituximab either alone or together with SE12C3 after tumors had achieved an average size of 100 mm3. Whereas treatment with SE12C3 alone had little effect on the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells, it significantly enhanced the inhibitory effect of rituximab on tumor growth (Figure 4A). Consistent with these findings, hSIRPα‐DKO mice treated for 3 weekly cycles with the combination of SE12C3 and rituximab survived for a significantly longer time compared with those treated with either SE12C3 or rituximab alone (Figure 4A). Similarly, treatment with the combination of 040 and rituximab had a greater inhibitory effect on tumor growth and prolonged survival to a greater extent compared with treatment with either Ab alone (Figure 4B). The inhibitory effect of 040 plus rituximab on tumor growth was less pronounced than that of SE12C3 plus rituximab, although both combination therapies prolonged survival by similar extents (Figure 4B). These observations thus suggested that disruption by SE12C3 of the CD47‐SIRPα interaction is likely important for the suppressive effect of this mAb on tumor growth. We also examined possible adverse effects of treatment with SE12C3 in hSIRPα‐DKO mice. Blood biochemical analysis revealed that treatment with SE12C3 resulted in no significant changes in blood biochemical parameters compared with control IgG and vehicle administration, whereas the control IgG‐treated or SE12C3‐treated mice exhibited a small decrease in blood glucose concentration compared with the vehicle‐treated animals (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Effect of anti‐human SIRPα Abs on rituximab‐induced inhibition of the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells in hSIRPα‐DKO mice. Tumor volume (left panels) and survival curves (right panels) were determined for hSIRPα‐DKO mice injected s.c. with Raji cells and treated i.p. with control IgG, a mAb to human SIRPα (SE12C3 [A] or 040 [B]), rituximab, or rituximab plus either SE12C3 (A, B) or 040 (B) according to the indicated schedule beginning after tumor volume had achieved an average value of 100 mm3. Data are means ± SEM for 10 (control IgG or SE12C3) or 12 (rituximab or SE12C3‐rituximab) mice in 2 separate experiments (A); or for 11 mice (control IgG, 040, rituximab, 040 plus rituximab, or SE12C3 plus rituximab) in 2 separate experiments (B). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; NS, not significant (2‐way ANOVA and Tukey's test [left panels] or the log‐rank test [right panels])

Table 1.

Blood biochemical analysis for hSIRPα‐DKO mice injected i.p. with vehicle (−), control IgG, or SE12C3 three times a week for 2 wk

| (−) | Control IgG | SE12C3 | |

| AST (U/L) | 74 ± 12.11 | 136 ± 31.66 | 97 ± 21.41 |

| ALT (U/L) | 22.5 ± 2.06 | 43 ± 10.68 | 21.33 ± 1.61 |

| ALP (U/L) | 482 ± 51.36 | 523.7 ± 64.83 | 499.3 ± 48.97 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 34 ± 14.07 | 49 ± 8.47 | 38.33 ± 3.74 |

| ALB (mg/dL) | 3.48 ± 0.08 | 3.2 ± 0.15 | 3.50 ± 0.13 |

| GLU (mg/dL) | 164.5 ± 15.09a | 113.7 ± 13.5 | 123.3 ± 7.074 |

| PL (mg/dL) | 186.5 ± 28.14 | 165.7 ± 3.91 | 178.7 ± 7.88 |

| BIL (mg/dL) | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.04 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 22.3 ± 2.17 | 26.2 ± 2.04 | 21.3 ± 1.27 |

| CHO (mg/dL) | 106.5 ± 12.61 | 97.67 ± 2.26 | 100.7 ± 3.99 |

| CRE (mg/dL) | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.19 |

ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BIL, total bilirubin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CHO, total cholesterol; CRE, creatinine; GLU, glucose; PL, phospholipid; TG, triglyceride.

Data are means ± SEM for 4 (vehicle) or 6 (control IgG or SE12C3) mice per group.

P < .05 vs control IgG (1‐way ANOVA and Tukey's test).

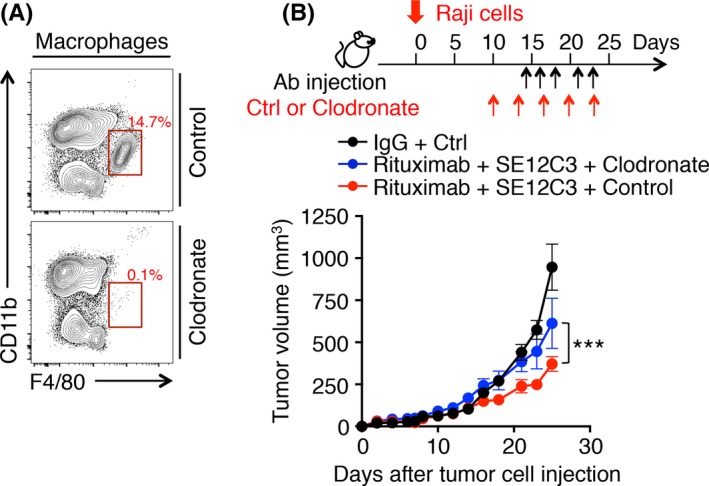

3.4. Importance of macrophages for the antitumor effect of combination therapy with SE12C3 and rituximab in vivo

We finally investigated whether macrophages contribute to the inhibitory effect of combination therapy with SE12C3 and rituximab on the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells in hSIRPα‐DKO mice. Effective depletion of F4/80+CD11b+ splenic macrophages was apparent as early as 3 days after a single i.v. injection of clodronate liposomes (Figure 5A). Such macrophage depletion was associated with marked attenuation of the inhibitory effect of combination treatment with SE12C3 and rituximab on the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells (Figure 5B). These results thus suggested that macrophages, indeed, contribute, at least in part, to the antitumor effect of the combination of SE12C3 and rituximab.

Figure 5.

Importance of macrophages for the antitumor effect of combination therapy with SE12C3 and rituximab in vivo. A, Splenocytes isolated from hSIRPα‐DKO mice 3 days after i.v. injection with either PBS liposomes (Control) or clodronate liposomes were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and for CD45, CD11b and F4/80 for analysis by flow cytometry. The relative number of F4/80+ CD11b+ cells (macrophages) is expressed as a percentage of all viable CD45+ cells in each plot. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments. B, hSIRPα‐DKO mice were injected with PBS liposomes or clodronate liposomes, Raji cells, and the indicated Abs according to the indicated schedule. Tumor volume was measured at the indicated times. Data are means ± SEM for 5 mice of each group. ***P < .001 (2‐way ANOVA and Tukey's test)

4. DISCUSSION

The CD47‐SIRPα axis has been implicated as a promising target for immunotherapy of cancer.17, 28 Indeed, blockade of CD47‐SIRPα interaction has been shown to contribute to the elimination of tumor cells in xenograft or syngeneic mouse models.22, 29, 30, 31 However, the antitumor effect of Abs to human SIRPα in immunodeficient mice transplanted with human cancer cells has remained unclear because such Abs have failed to bind to mouse SIRPα expressed on mouse macrophages. We have now shown that the SE12C3 mAb to human SIRPα, which prevents the human CD47‐SIRPα interaction, markedly enhanced phagocytosis of Ab‐opsonized human tumor cells by BMDM from immunodeficient mice engineered to express human SIRPα (hSIRPα‐DKO mice). Such an effect of SE12C3 was not apparent with BMDM from control DKO mice. In addition, SE12C3 markedly enhanced rituximab‐induced suppression of the growth of tumors formed by Raji cells in hSIRPα‐DKO mice. The survival of tumor‐bearing mice treated with both SE12C3 and rituximab was also markedly prolonged in comparison with that of those treated with either Ab alone. Moreover, depletion of macrophages in hSIRPα‐DKO mice resulted in attenuation of the suppressive effect of combination therapy with SE12C3 and rituximab on tumor growth, suggesting the importance of macrophages for this antitumor action in vivo. Together, these results thus indicate that blocking Abs to human SIRPα may prove beneficial for potentiation of the antitumor effects of Abs to tumor‐specific antigens such as rituximab. With regard to potential adverse effects, SE12C3 did not induce marked changes in blood biochemical parameters compared with control IgG.

We found that 040, a nonblocking Ab to human SIRPα, also enhanced phagocytosis of Ab‐opsonized tumor cells by BMDM from hSIRPα‐DKO mice as well as promoted inhibition of Raji tumor growth by rituximab in these mice, although these effects of 040 were smaller than those of SE12C3. Indeed, p84, a nonblocking Ab to mouse SIRPα, was previously shown to enhance both the rituximab‐induced ADCP activity of macrophages as well as inhibition of tumor growth by rituximab.22 It is possible that nonblocking Abs to SIRPα promote SIRPα endocytosis in macrophages, resulting in effects similar to those of blockade of CD47‐SIRPα interaction. Moreover, Abs to human SIRPα may merely bridge between tumor cells and macrophages to enhance phagocytosis. However, we showed that the expression of SIRPα on Raji and BT474 was minimal (Figure S2). By contrast, ligation by anti‐SIRPα Abs of both SIRPα and Fc receptors, such as FcγRIII, on macrophages might also transmit activation signals as well as inhibitory signals, leading to promotion of the phagocytosis of tumor cells. Further studies will be necessary to understand the detailed molecular mechanism underlying the anti‐SIRPα Ab‐enhanced phagocytosis of tumor cells by macrophages.

During preparation of this manuscript, a blocking Ab to human SIRPα (KWAR23) was shown to promote the antitumor effect of rituximab in human SIRPA knock‐in immunodeficient mice, in which the extracellular domain of mouse SIRPα was replaced by that of human SIRPα.32, 33 These results thus provide further support for the efficacy of blocking Abs to human SIRPα as anticancer drugs. Genetically modified mice such as hSIRPα‐DKO and human SIRPA knock‐in immunodeficient mice can, thus, serve as models for preclinical validation of Abs to human SIRPα. Transgenic mice suitable for transplantation of human hematopoietic stem cells have recently been developed,34, 35 with these so‐called “humanized mice” also likely to prove useful for preclinical validation of the antitumor effects of checkpoint inhibitors such as Abs to human PD‐1 or to human CTLA‐4 on T cells or to human SIRPα on macrophages.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Matozaki T received research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. The other authors have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. J. Bühring for the mouse mAb to human SIRPα (clone SE12C3), M. Miyasaka for the rat mAb to mouse SIRPα (clone MY‐1), S. Shirahata for CHO‐Ras cells, and N. Honma for the SIRPαv2 plasmid and for CHO‐Ras cells stably expressing human or mouse SIRPα.

Murata Y, Tanaka D, Hazama D, et al. Anti‐human SIRPα antibody is a new tool for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:1300–1308. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13548

Funding information

Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (26291022): Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (P‐CREATE); Terumo Foundation for Life Sciences and Arts; Uehara Memorial Foundation, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd

REFERENCES

- 1. Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Clinical activity, toxicity, biomarkers, and future development of CTLA‐4 checkpoint antagonists. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:573‐586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, et al. PD‐1 and PD‐L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou Q, Facciponte J, Jin M, et al. Humanized NOD‐SCID IL2rg−/− mice as a preclinical model for cancer research and its potential use for individualized cancer therapies. Cancer Lett. 2014;344:13‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shultz LD, Goodwin N, Ishikawa F, et al. Human cancer growth and therapy in immunodeficient mouse models. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2014;2014:694‐708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matozaki T, Murata Y, Okazawa H, et al. Functions and molecular mechanisms of the CD47‐SIRPα signalling pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:72‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barclay AN, Van den Berg TK. The interaction between signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) and CD47: structure, function, and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:25‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seiffert M, Brossart P, Cant C, et al. Signal‐regulatory protein α (SIRPα) but not SIRPβ is involved in T‐cell activation, binds to CD47 with high affinity, and is expressed on immature CD34+CD38− hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2001;97:2741‐2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ishikawa‐Sekigami T, Kaneko Y, et al. SHPS‐1 promotes the survival of circulating erythrocytes through inhibition of phagocytosis by splenic macrophages. Blood. 2006;107:341‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okajo J, Kaneko Y, Murata Y, et al. Regulation by Src homology 2 domain‐containing protein tyrosine phosphatase substrate‐1 of α‐galactosylceramide‐induced antimetastatic activity and Th1 and Th2 responses of NKT cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:6164‐6172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saito Y, Iwamura H, Kaneko T, et al. Regulation by SIRPα of dendritic cell homeostasis in lymphoid tissues. Blood. 2010;116:3517‐3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oldenborg PA. CD47: a cell surface glycoprotein which regulates multiple functions of hematopoietic cells in health and disease. ISRN Hematol. 2013;2013:614619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, et al. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288:2051‐2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okazawa H, Motegi S, Ohyama N, et al. Negative regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by the CD47‐SHPS‐1 system. J Immunol. 2005;174:2004‐2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaiswal S, Jamieson CH, Pang WW, et al. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 2009;138:271‐285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 2009;138:286‐299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chao MP, Weissman IL, Majeti R. The CD47‐SIRPα pathway in cancer immune evasion and potential therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:225‐232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matlung HL, Szilagyi K, Barclay NA, et al. The CD47‐SIRPα signaling axis as an innate immune checkpoint in cancer. Immunol Rev. 2017;276:145‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takenaka K, Prasolava TK, Wang JC, et al. Polymorphism in Sirpa modulates engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1313‐1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Theocharides AP, Jin L, Cheng PY, et al. Disruption of SIRPα signaling in macrophages eliminates human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells in xenografts. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1883‐1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iwamoto C, Takenaka K, Urata S, et al. The BALB/c‐specific polymorphic SIRPA enhances its affinity for human CD47, inhibiting phagocytosis against human cells to promote xenogeneic engraftment. Exp Hematol. 2014;42:163‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yi T, Li J, Chen H, et al. Splenic dendritic cells survey red blood cells for missing self‐CD47 to trigger adaptive immune responses. Immunity. 2015;43:764‐775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yanagita T, Murata Y, Tanaka D, et al. Anti‐SIRPα antibodies as a potential new tool for cancer immunotherapy. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e89140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Strowig T, Rongvaux A, Rathinam C, et al. Transgenic expression of human signal regulatory protein alpha in Rag2−/−γc −/− mice improves engraftment of human hematopoietic cells in humanized mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13218‐13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verjan Garcia N, Umemoto E, Saito Y, et al. SIRPα/CD172a regulates eosinophil homeostasis. J Immunol. 2011;187:2268‐2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Motegi S, Okazawa H, Ohnishi H, et al. Role of the CD47‐SHPS‐1 system in regulation of cell migration. EMBO J. 2003;22:2634‐2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Motegi S, Okazawa H, Murata Y, et al. Essential roles of SHPS‐1 in induction of contact hypersensitivity of skin. Immunol Lett. 2008;121:52‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murata Y, Mori M, Kotani T, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of R3 subtype receptor‐type protein tyrosine phosphatases and their complex formations with Grb2 or Fyn. Genes Cells. 2010;15:513‐524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiskopf K. Cancer immunotherapy targeting the CD47/SIRPα axis. Eur J Cancer. 2017;76:100‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, et al. Anti‐CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Cell. 2010;142:699‐713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao XW, van Beek EM, Schornagel K, et al. CD47‐signal regulatory protein‐α (SIRPα) interactions form a barrier for antibody‐mediated tumor cell destruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18342‐18347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weiskopf K, Ring AM, Ho CC, et al. Engineered SIRPα variants as immunotherapeutic adjuvants to anticancer antibodies. Science. 2013;341:88‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Herndler‐Brandstetter D, Shan L, Yao Y, et al. Humanized mouse model supports development, function, and tissue residency of human natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E9626‐E9634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ring NG, Herndler‐Brandstetter D, Weiskopf K, et al. Anti‐SIRPα antibody immunotherapy enhances neutrophil and macrophage antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E10578‐E10585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rongvaux A, Takizawa H, Strowig T, et al. Human hemato‐lymphoid system mice: current use and future potential for medicine. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:635‐674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Theocharides AP, Rongvaux A, Fritsch K, et al. Humanized hemato‐lymphoid system mice. Haematologica. 2016;101:5‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials