ABSTRACT

Immune molecules, which have been found to be important in tumor microenvironment, seem prospective in tumor therapy, but they are still not effective enough to use in clinical practice. C-C motif chemokine 22 (CCL22) exists in various malignancies and correlates with migration of regulatory T cells, but its clinical significance in gastric cancer is still unclear. In this study, a combined data set of 466 patients with gastric cancer after surgical resection, comprised of a discovery (n = 319) and a validation data set (n = 147), was enrolled. CCL22 expression was assessed by immunohistochemical staining and we evaluated prognostic values of CCL22 staining and clinical outcomes with use of Kaplan-Meier curve and Multivariate Cox regression analysis. Positive CCL22 expression predicted adverse overall survival independent of traditional pathological grade. Multivariate analysis defined CCL22 and TNM stage as two independent prognostic factors for overall survival. Besides, in patients with TNM stage II/III disease, the rate of overall survival was higher among patients with CCL22-positive tumors who were treated with 5-fluorouracil based adjuvant chemotherapy than that among those who were not (P = 0.012, P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, in discovery, validation and combined data set). But for these with CCL22-negative tumors, whether to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy showed no statistical significance (P = 0.595, P = 0.085 and P = 0.252, respectively). To conclude, CCL22 was identified as an independent adverse prognostic immunobiomarker for patients with gastric cancer after surgery, which is associated with tumor-infiltrating immunocytes and could be incorporated into TNM staging system to redefine a high-risk subgroup who were more likely to benefit from 5-fluorouracil based adjuvant chemotherapy.

KEYWORDS: adjuvant chemotherapy, C-C motif chemokine 22, gastric cancer, prognosis, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Chemotherapy was the standard of care for patients with relatively advanced gastric cancer and thanks to the introduction of new adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, overall survival (OS) among patients with gastric cancer has increased significantly during the past few years.1-3 However, since gastric cancer was usually asymptomatic in early stages, researchers found it difficult to stratify and treat those patients.4 The lack of a reliable standard to distinguish those really at high risk has made it hard for us to identify patients who would benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy when considering OS.4,5

To solve this problem, many researchers tried to measure the possibility to stratify gastric cancer patients according to biomarkers of tumor tissue and found some useful factors that can be used to identify high-risk gastric cancer.6,7 Besides, clinical researchers have explored possibilities of generating chemotherapy before surgery to shrink the tumor, or as adjuvant therapy after surgery to destroy remaining cancer cells.8 Although previous findings held promise, the relative benefits of different drugs, alone or in combination, were still unclear and it remained hard for us to use what we have found to predict exact benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.9

Currently several clinicopathological indicators, such as Lauren classification, differentiation, tumor, node and metastasis (TNM) stage, were widely used for predicting prognosis of gastric cancer patients.10,11 However, these factors had limitations and were not accurate enough when used in clinical circumstances since gastric cancer was a complex, heterogeneous disease with widely distinct prognosis.12

Although it remains unclear how and when during multi-step process the immune system is first alerted to the presence of cancer cells and begins its initial, often unsuccessful attempts at eliminating them, it plays an important role in tumor microenvironment,13 and among the molecules with the best promise might be those related closely to our immune system, which indicates that study of this field might help to improve current prognostic models and shed light on new treatment for the disease.14,15 Hence, previous studies have explored the possibilities to inhibit secretion of suppressive cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and interleukin-10, to reverse the progression of tumor without getting meaningful results, it's high time that we paid more attention to factors that recruit and transform suppressive immunocytes, like regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which may help to establish a new treatment option.16-17 Therefore, we suggested a systematic search for immunobiomarkers that could be used to identify and stratify tumors to predict prognosis more precisely.

Chemokines were functionally divided into homeostatic and inflammatory groups. Previous studies have identified a multifaceted functional role of chemokine signaling ways in diverse cellular processes such as cellular maturation, angiogenesis and recruiting immunocytes.18 C-C motif chemokine 22 (CCL22), also known as macrophage-derived chemokine, was found abundantly expressed in many types of malignancies.19-23 Evidence obtained from studies suggested that CCL22-CCR4 signaling axis could help peritoneal tumors to migrate, survive, and establish cell cluster-type metastasis, in contrast to later stages of tumor development, in which CCL22 activation was needed.24 Moreover, according to recent studies, tumor cells could transform CD4+ T cells into Tregs, resulting in high risk of immune escape.25-26 In previous studies, we have discovered tumor infiltrating Foxp3+ cells, often regarded as Tregs and could be recruited by CCL22, as an independent marker to identify patient outcomes, which pushed us to better identify the exact role of this chemokine.27

In preliminary experiments, we observed that CCL22 was expressed abnormally in gastric cancer and it has been revealed that CCR4, the main receptor of CCL22, was overexpressed in human gastric cancer.28-29 However, the prognostic and chemotherapeutic significance of CCL22 expression level and its relationship with gastric cancer progression remained to be unknown, which needed to be further studied.

In this study, we indicated CCL22 expression level in gastric cancer by immunohistochemical staining and assessed its association with OS and benefit from 5- fluorouracil based adjuvant chemotherapy with use of subgroup analysis. Besides, the prognostic value of CCL22 mRNA level was evaluated in different kinds of tumors with use of bioinformatics. These results may elucidate potential prognostic significance of CCL22 and correlative immunocytes, like macrophages, Tregs, and redefine a subgroup of patients who are more likely to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.

Results

Patients' characteristics and immunohistochemical findings

To investigate whether CCL22 expression was related to gastric cancer development and progression, we evaluated expression with use of immunohischemistry in the clinical specimens of 466 patients and assessed its association with OS and benefit from 5- fluorouracil based adjuvant chemotherapy with use of subgroup analysis in discovery, validation and combined data set (Fig. 1). CCL22 was predominately localized in cytoplasm and its expression was elevated in gastric cancer tissues. Specific expression of cytoplasmic CCL22 was observed mainly in tumor cells and some stromal cells and staining intensity varied (Fig. 2A, 2B and Supplementary Fig. 1). Analysis of stained tissue sections indicated a minor subgroup of tumors that lacked CCL22, as compared with those that had intense CCL22 expression in cytoplasm, thus scored as CCL22-positive (52.4% in discovery data set and 55.8% in validation data set). Detailed characteristics were summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The median follow-up time of the whole cohort was 45 months (range: 2–79 months).

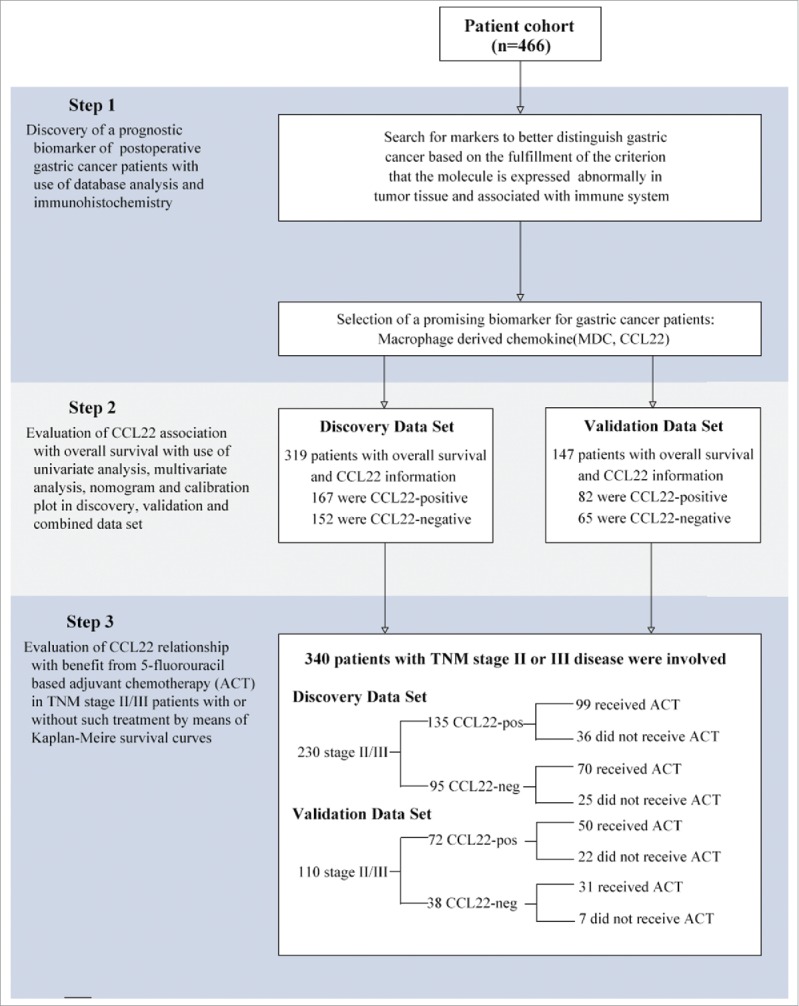

Figure 1.

Study design. 466 gastric cancer patients, who have undergone gastrectomy with standard D2 lymph node resection in Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University during 2007–2008, were enrolled in our study. Preliminary test was generated by immunohistochemistry. The relationship between CCL22 expression and survival was analyzed based on TNM staging system. The relationship between CCL22 expression and benefit from chemotherapy was analyzed in a pooled database with 230 patients in discovery data set and 110 patients in validation data set with TNM stage II/III disease.

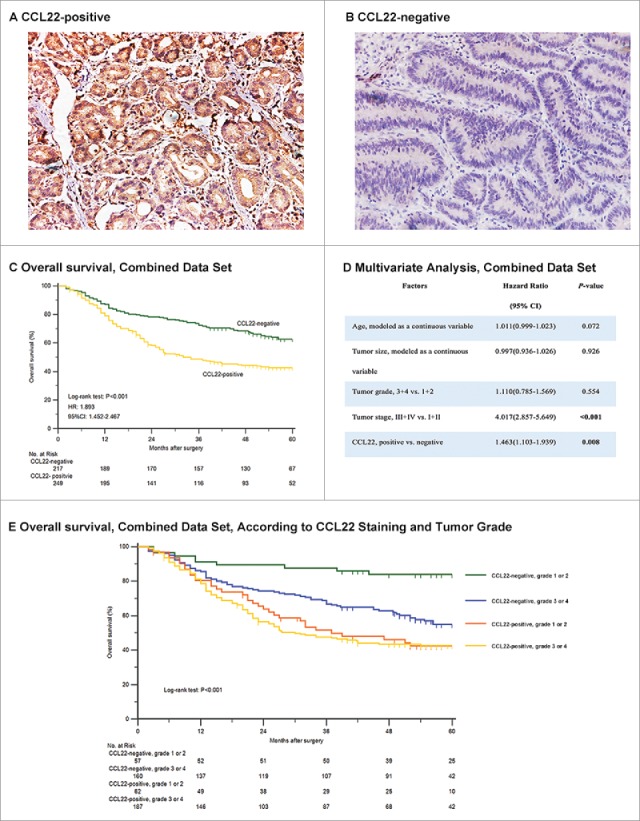

Figure 2.

Relationship between CCL22 expression and overall survival among patients with gastric cancer in combined data set. Representative images showed that there existed CCL22-positive tumors (A) and CCL22-negative tumors (B) simultaneously. CCL22-positive tumors were associated with a lower rate of 5-year overall survival compared with those with negative CCL22 expression (C) and the result was validated by generating multivariate analysis based on cox proportional hazards regression model containing age, tumor size, tumor grade, tumor stage and CCL22 expression (D). The association between CCL22-positive tumors and a lower rate of 5-year overall survival was independent of pathological tumor grade (E).

Table 1.

Hazard Ratios for Risk of Mortality in Gastric Cancer Patients Receiving 5-FU Based Adjuvant Chemotherapy (ACT) or Not According to CCL22 Staining in Stage II/III Patients.

| Risk of Mortality |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients |

ACT (Yes vs No) |

||||

| Patient cohort | Variable | No. | % | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Discovery Data Set | |||||

| CCL22 | 230 | 0.657(0.434-0.953) | 0.027 | ||

| Positive | 135 | 58.7 | 0.555(0.348-0.887) | 0.014 | |

| Negative | 95 | 41.3 | 0.848(0.459-1.563) | 0.598 | |

| Validation Data Set | |||||

| CCL22 | 110 | 0.290(0.174-0.482) | <0.001 | ||

| Positive | 72 | 65.5 | 0.220(0.117-0.414) | <0.001 | |

| Negative | 38 | 34.5 | 0.450(0.177-1.145) | 0.095 | |

| Combined Data Set | |||||

| CCL22 | 340 | 0.521(0.386-0.701) | <0.001 | ||

| Positive | 207 | 60.9 | 0.417(0.288-0.605) | <0.001 | |

| Negative | 133 | 39.1 | 0.743(0.446-1.239) | 0.257 | |

Abbreviation: HR, Hazard Ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. P-value < 0.05 marked in bold font shows statistical significance

Correlations between CCL22 expression and characteristics of patients

CCL22 expression was found positively related with T classification (P < 0.001, P = 0.004 and P < 0.001) and TNM stage (all P < 0.001) in discovery, validation and combined data set. Besides, CCL22 expression was associated with tumor localization (P = 0.037 and P = 0.010), Lauren classification (P = 0.014 and P = 0.001) and N classification (P = 0.040 and P = 0.006) in discovery and combined data set. Interestingly, CCL22 expression was also found related with distant metastasis (P = 0.032) in discovery data set. The detailed analysis was shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Relationship between CCL22 expression and overall survival among patients with gastric cancer

To evaluate the relationship between CCL22 expression and survival among patients in different stages, we used Kaplan–Meier curves to compare survival of the two subgroups. Tumor stage was obtained according to AJCC TNM classification system.30 The analysis showed that the survival rate of 5-year OS was lower among 249 patients with CCL22-positive tumors than that among 217 patients with CCL22-negative tumors in the whole cohort (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2C). The result generated in discovery and validation set also showed statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 2).

In a multivariate analysis that included age, size, tumor grade, tumor stage and CCL22 staining, which were all originally regarded as effective variables in univariate analysis (Supplementary Table 3), the association remained significant that the hazard ratio for CCL22 expression level was 1.463 (95%CI, 1.103 to 2.939; P = 0.008) (Fig. 2D). These associations were not confounded by risk factors that were known to affect survival rates among gastric cancer patients, such as age, tumor size and tumor grade.

CCL22-positive tumors were more common among patients with higher pathological grade (Supplementary Table 2). However, patients with CCL22-positive tumor had lower rate of survival no matter the pathological grade was high (3 or 4) or low (1 or 2), which was also consistent with the result in multivariate analysis (Fig. 2D and 2E).

Prognostic nomogram and calibration plots of gastric cancer

Based on results arising from univariate and multivariate analysis, we constructed a nomogram to predict OS at 3 and 5 years after surgery (Supplementary Fig. 3A). The predictors included age, tumor size, tumor grade, TNM stage and CCL22 staining, all of which were significant prognostic indicators for OS according to preliminary analysis. The calibration plots of nomogram were shown for 3- and 5-year predictions (Supplementary Fig. 3B and 3C).

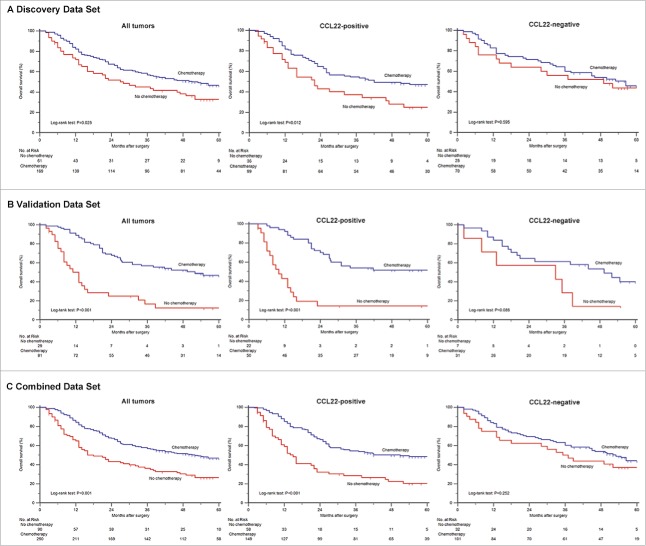

Figure 3.

Relationship between CCL22 expression and benefit from 5-fluorouracil based adjuvant chemotherapy. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival in patients with stage II/III disease received postsurgical adjuvant chemotherapy according to CCL22 expression level. Among patients in discovery, validation and combined data sets, treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a higher rate of 5-year overall survival (P = 0.025, A; P<0.001, B; P<0.001, C). Besides, treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy was strongly associated with a higher rate of 5-year overall survival in the CCL22-positive subgroup in all sets (P = 0.012, P<0.001, P<0.001, respectively), but it was not associated with a higher rate of survival in the CCL22-negative subgroup (P = 0.595, P = 0.085, P = 0.252, respectively).

CCL22 expression level and benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer patients

To evaluate whether patients with CCL22-positive tumors would benefit from 5-fluorouracil based adjuvant chemotherapy, we assessed relationship between CCL22 with OS among patients who either did or did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy in discovery, validation and combined set.

A preliminary test involving 230 patients with stage II/III disease in discovery data set showed that for patients who were scored as CCL22-positive, adjuvant chemotherapy had a significant better impact on prognosis (P < 0.001, Fig. 3A). However, such treatment was not associated with OS in CCL22-negatve tumors (P = 0.595, Fig. 3A). Hence, it demonstrated a strong association between adjuvant chemotherapy and reduced risk of compromised survival in patients with CCL22-positive tumors (HR, 0.555; 95%CI, 0.348-0.887; P = 0.014, Table 1) but not in patients with CCL22-negative tumors (HR, 0.848; 95%CI, 0.459-1.563; P = 0.598, Table 1).

Based on previous studies, we thus decided to validate our hypothesis in the database of 110 (validation data set) and 340 (combined data set) patients with stage II/III gastric cancer.

The results confirmed that treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a higher rate of OS in both validation data set (P < 0.001) and combined data set (P < 0.001) of the CCL22-positive subgroup, whereas such result was not observed in CCL22-negative subgroup (Fig. 3B and 3C). Besides, the survival probability of CCL22-positive TNM stage II/III subgroup was higher compared with CCL22-negative subgroup in both validation data set (HR, 0.220; 95%CI, 0.117-0.414; P < 0.001 vs. HR, 0.450; 95%CI, 0.177-1.145; P = 0.095) and combined data set (HR, 0.417; 95%CI, 0.288-0.605; P < 0.001 vs. HR, 0.743; 95%CI, 0.446-1.239; P = 0.257) as shown in Table 1.

Prognostic value of CCL22 mRNA level in gastric cancer and other cancer types

To further elucidate the prognostic value of CCL22 in a wider range, we used fresh patient-derived surgical resected tumor tissues (n = 12) to evaluate the relationship between CCL22 protein and mRNA expression level. As a result, we found that the protein expression level of CCL22 detected by the antibody paralleled its mRNA expression level (Supplementary Fig. 4A). In addition, as CCL22 mRNA level was found higher in primary tumors than in normal tissues (P = 0.008, Supplementary Fig. 4B), we further used data of TCGA to assess the relationship between CCL22 mRNA level and survival in patients with stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) database and found that high CCL22 mRNA expression could also predict adverse prognosis (P = 0.044, Supplementary Fig. 4C). In addition, we used the same method to analyze esophageal cancer (ESCA) database and brain lower grade glioma (LGG) database and found similar results (P = 0.026 and P = 0.047, Supplementary Fig. 4D and 4E) as we indicated in STAD database.

Relationship between CCL22 expression and tumor-infiltrating immunocytes

We further investigated the relationship between CCL22 and tumor-infiltrating immunocytes in serial tissue sections stained by primary antibody with use of Pearson's or Spearman's correlation analysis. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, CCL22 expression was found positively associated with infiltration of Foxp3+ Tregs, CD68+ macrophages and negatively associated with CD8+ T cells.

Discussion

Prognostic biomarkers were essential to patient risk stratification, and to decide whether to recommend adjuvant therapy and a more frequent follow-up after surgery in patients with early-stage disease.31 Currently, depth of tumor invasion, lymph nodes metastasis, Lauren classification remained to be important among a handful of prognostic factors that were considered in the development and treatment of gastric cancer patients.10,11 Variables such as lymphovascular and perineural invasion by cancer cells, though very promising, have been proved difficult to standardize because of technical problems inherent in the visual analysis and subjective definition of these features.32 Microarray-derived gene-expression signatures from stem cells and progenitor cells showed promise, but they were also hard to translate into clinical practice.33,34 Moreover, it seemed harder for researchers to identify a sufficiently valuable prognostic biomarker that was also predictive of benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.35

Previous studies indicated that CCL22, of which receptor was revealed to be mainly CCR4, was often related with migration of Tregs, cancer progression, metastasis and other adverse variables in many kinds of tumors such as ovarian cancer, lung cancer and breast cancer.22-28,36,37 However, the exact value, as well as underlying mechanism, of CCL22 expression in gastric cancer has not been well explained.

Similar to abnormally expressed CCL22 in this study, it has been reported that CCR4 was also expressed abnormally in human gastric cancer.28,29 Besides, tumor-secreted CCL17 and CCL22 were thought to play an important role in immune evasion by binding CCR4, which was mainly expressed on the surface of Tregs, in nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma.12,38 And according to previous research, melanoma could be completely rejected when approximately 99% Tregs were depleted.39 We have also observed that CCL22 expression was associated with high infiltration of Foxp3+ Tregs and low infiltration of CD8+ T cells, which indicated the potential immunosuppressive effect of this chemokine. Thus, a similar mechanism involving CCL22 and CCR4 might also be operative for immune evasion in gastric cancer.

This study defined CCL22 as an adverse prognostic biomarker that could be used to stratify postoperative gastric cancer patients. Of particular interest, we found that the improvement in risk stratification was not dependent on traditional pathological grade, which showed us that this chemokine could be key to tumor process other than traditional molecular biological factors. Thus, we advocate for the use of CCL22 expression to better regulate management before and after surgery. For example, gastric cancer patients with positive CCL22 expression need to undergo adjuvant therapy and a more frequent follow-up after surgery, though they may not be regarded as high-risk patients according to conventional clinicopathological features.

Since the immunohistochemistry score of CCL22 was positively correlated with its serum concentration and tumor bed was the main source of serum CCL22 in gastric cancer.40 It seemed possible that cancer cells could release CCL22 to tame tumor microenvironment and to recruit Tregs, which would eventually risk people a higher possibility of immune escape and result in a lower survival rate and therapy resistance. Besides, previous studies found that cancer cells could secret cytokines to recruit and transform immune cells such as fibroblasts, neutrophils, and macrophages, which had a great importance in the immunosuppressive microenvironment.12,41-42 Tumor-associated macrophages, which were thought to be ineffective antigen-presenting cells, could also produce CCL22 and attract Tregs that inhibited T cell activation.43 In addition, such result may be attributable to the conversion of Tregs. Gastric cancer cells could directly convert CD4+ naive T cells to Tregs by its interaction with TGF-β.25,26,44 Thus, research on how cancer cells react with tumor microenvironment may shed light on new immune therapy by interposing such signaling ways. For instance, as anti-CCR4 mAb is currently being developed for clinical use, we believe that molecular-targeted therapy and blockade of CCL22/CCR4 pathways using anti-CCR4 mAb could be a potential approach for gastric cancer therapy.

In addition, among patients who were diagnosed as TNM II/III stage tumor, only those with positive CCL22 expression were able to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, which seemed promising to stratify patients more precisely. Several researchers reported that the production of CCL22 could be suppressed via down-regulating STAT1 pathway45,46 and 5-fluorouracil based treatment can affect in a STAT1-dependent manner to lead to Fas-mediated apoptosis.47 Hence, as previously described, tumor-infiltrating CD68+ macrophages could increase the response of 5-flourouracil adjuvant therapy in many types of malignancies, like stage III colorectal cancer,48 and we found that CCL22 expression was positively associated with infiltration of CD68+ macrophages in tumor microenvironment. Thus, we believe that this chemokine, which could also be partly secreted by macrophages, should be the key point in such process and intervention of this signaling way could regulate therapy resistance.

Given the exploratory design of the study, these results await to be confirmed within the framework of randomized clinical trials, in conjunction with genomic DNA sequencing studies and the exact underlying molecular mechanism involved will be further elucidated in our following studies.

In conclusion, our study clearly demonstrates that high CCL22 expression, independent of conventional clinicopathological variables, strongly associates with poor outcomes of gastric cancer patients and could further stratify patients with significantly different OS. This finding provides a novel independent predictor for prognosis and may improve current predictive systems in terms of counselling patients. Besides, an abundance of CCL22 expression can redefine a high-risk subgroup of patients with TNM stage II/III gastric cancer who are more likely to benefit from 5-fluorouracil based adjuvant chemotherapy, which could help to build up a more customized way of treatment.

Patients and methods

Patients and specimens

A cohort comprising 466 gastric cancer patients who have received gastrectomy with standard D2 lymph node resection was obtained from Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Shanghai, China) from Aug.2007 to Dec.2008. The discovery data set (n = 319) contained patients who received surgery during Aug.2007-Aug.2008 and the validation data set (n = 147) contained those during Sep.2008-Dec.2008. None of the patients received any preoperative anticancer treatment and those who were diagnosed as tumors with excessive lymph node metastasis were candidates for receiving postsurgical adjuvant chemotherapy. Collectively, there were 181 (56.7% in discovery data set) and 87 (59.2% in validation data set) patients received 5-fluorouracil based adjuvant chemotherapy at least one cycle. OS were defined as time between surgery and death or last visit. Hence, fresh patient-derived surgical resected gastric cancer tissues (n = 12) were collected from Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Shanghai, China). All specimens fulfilled certain study criteria as previously described27 and were granted by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. Besides, clinicopathological and genomic data of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) database, esophageal cancer (ESCA) database and brain lower grade glioma (LGG) database were downloaded from the UCSC cancer browser (http://genome-cancer.ucsc.edu).49,50

Immunohistochemical staining and analysis of tissue microarray

Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded serial tissue sections were applied for tissue microarray and the following immunohistochemical staining using primary antibody against CCL22 (Ab9847, diluted 1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), CD8 a (Ab17147, diluted 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), CD68 (Ab125212, diluted 1:400, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and Foxp3 (Ab22510, diluted 1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). The staining protocol and tissue microarray were performed as previously described.51,52 The result of immunohistochemistry was reviewed by two pathologists who were blind to the data of patients independently with use of light microscope. If the result of the same sample was discordant, they would discuss to reach the final score. The tumors with strong expression of CCL22 in cytoplasm, either in all or most of cancer cells, were scored as CCL22-positive. Respectively, all tumors which lacked CCL22 expression or just had faint expression of CCL22 in cytoplasm were scored as CCL22-negative. Staining score of each section was generated by counting staining intensity of each cell using semi-quantitative immunoreactivity scoring system giving a range of 0–300 as previously described.53,54 Statistical analysis was operated by a third researcher who did not have a role in previous procedures.

Immunohistochemical staining and qRT-PCR analysis of fresh tumor tissues

Fresh patient-derived surgical resected tumor tissues (n = 12) were used for building tissue sections. We applied immunohistochemical staining with use of primary antibody against CCL22 (Ab9847, diluted 1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and measured staining intensity of each section. Moreover, the same tumor tissues (n = 12) were minced in TRIzol and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's protocol (Life Technologies). The cDNA was generated by the Takara RNA PCR Kit. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara) agent in StepOne Plus (Life Technologies) to detect mRNA expression. The primers of CCL22: forward, CGCGTGGTGAAACACTTCTA; reverse, CGGCACAGATCTCCTTATCC. Besides, GAPDH expression was used to normalize CCL22 expression.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was applied by using SPSS software version 23.0 and Medcalc for windows (version 12.7.0.0; MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Pearson's chi-square test, Spearman's correlation analysis and Fisher's exact test were used to compare variables. Patient subgroups were compared due to survival outcomes with use of Kaplan–Meier survival curves, log-rank tests, univariate and multivariate analysis (only factors which demonstrated statistical significance on OS in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis) based on the cox proportional hazards regression model. In addition, we applied R software version 3.0.2 and the ‘rms’ package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) to generate nomogram and calibration curves to predict OS according to the variables. Only Log-rank test P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and results were reported according to the REMARK (Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies) guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), 81472227, National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), 81471621, National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), 81501999, Science Foundation for The Youth Scholars of Zhongshan Hospital, 2017ZSQN19, National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), 31770851, Shanghai Sailing Program, 17YF1402200, Science Foundation for The Excellent Youth Scholars of Zhongshan Hospital, 2017ZSYQ17, National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), 81671628.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471621, 81472227, 81501999, 81671628 and 31770851), Shanghai Sailing Program (17YF1402200), Science Foundation for The Excellent Youth Scholars of Zhongshan Hospital (2017ZSYQ17) and Science Foundation for The Youth Scholars of Zhongshan Hospital (2017ZSQN19). All these study sponsors have no roles in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Author contributions

S. Wu, H. He and H. Liu for acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript; Y. Cao, R. Li, H. Zhang and H. Li for analysis and interpretation of data, technical and material support, and statistical analysis; Z. Shen, J. Qin and J. Xu for study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, obtained funding and study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Fujitani K, Yang HK, Mizusawa J, Kim YW, Terashima M, Han SU, Iwasaki Y, Hyung WJ, Takagane A, Park DJ, et al.. Gastrectomy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric cancer with a single non-curable factor (REGATTA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:309–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00553-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quintero-Aldana G, Jorge M, Grande C, Salgado M, Gallardo E, Varela S, López C, Villanueva MJ, Fernández A, Alvarez E, et al.. Phase II study of first-line biweekly docetaxel and cisplatin combination chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;76:731–7. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2839-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo DH, Ryu MH, Ryoo BY, Seo J, Lee MY, Chang HM, Lee JL, Lee SS, Kim TW, Kang YK. Improving trends in survival of patients who receive chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent gastric cancer: 12 years of experience at a single institution. Gastric Cancer: official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2015;18:346–53. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YC, Chiang TH, Chou CK, Tu YK, Liao WC, Wu MS, Graham DY. Association Between Helicobacter pylori Eradication and Gastric Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1113–24.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park HS, Jung M, Kim HS, Kim HI, An JY, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Kim YI, Chung HC, et al.. Proper timing of adjuvant chemotherapy affects survival in patients with stage 2 and 3 gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:224–31. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3949-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasui W, Oue N, Ito R, Kuraoka K, Nakayama H. Search for new biomarkers of gastric cancer through serial analysis of gene expression and its clinical implications. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:385–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boku N, Chin K, Hosokawa K, Ohtsu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S, Yamao T, Kondo H, Shirao K, Shimada Y, et al.. Biological markers as a predictor for response and prognosis of unresectable gastric cancer patients treated with 5-fluorouracil and cis-platinum. Clin Cancer Res: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1998;4:1469–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vita F Giuliani F, Galizia G, Belli C, Aurilio G, Santabarbara G, Ciardiello F, Catalano G, Orditura M. . Neo-adjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy of gastric cancer. Ann Oncol: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2007;18 Suppl 6:vi120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scartozzi M, Galizia E, Verdecchia L, Berardi R, Antognoli S, Chiorrini S, Cascinu S. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: across the years for a standard of care. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yaghoobi M, Bijarchi R, Narod SA. Family history and the risk of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:237–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima T, Takahashi T, Takagi K, Kuno K, Kajitani T. Comparison of 5-fluorouracil with ftorafur in adjuvant chemotherapies with combined inductive and maintenance therapies for gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1984;2:1366–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.12.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nature Immunol. 2013;14:1014–22. doi: 10.1038/ni.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devaud C, John LB, Westwood JA, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. Immune modulation of the tumor microenvironment for enhancing cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e25961. doi: 10.4161/onci.25961. PMID:24083084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science (New York, NY). 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gowda A, Ramanunni A, Cheney C, Rozewski D, Kindsvogel W, Lehman A, Jarjoura D, Caligiuri M, Byrd JC, Muthusamy N. Differential effects of IL-2 and IL-21 on expansion of the CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T regulatory cells with redundant roles in natural killer cell mediated antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. mAbs. 2010;2:35–41. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.1.10561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serrels A, Lund T, Serrels B, Byron A, McPherson RC, von Kriegsheim A, Gómez-Cuadrado L, Canel M, Muir M, Ring JE, et al.. Nuclear FAK controls chemokine transcription, Tregs, and evasion of anti-tumor immunity. Cell. 2015;163:160–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuscher K, Danelon G, Paoletti S, Stefano L, Schiraldi M, Petkovic V, Locati M, Gerber BO, Uguccioni M. Synergy-inducing chemokines enhance CCR2 ligand activities on monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1118–28. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godiska R, Chantry D, Raport CJ, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Leviten D, Mantovani A, Gray PW. Human macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC), a novel chemoattractant for monocytes, monocyte-derived dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1595–604. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olkhanud PB, Baatar D, Bodogai M, Hakim F, Gress R, Anderson RL, Deng J, Xu M, Briest S, Biragyn A. Breast cancer lung metastasis requires expression of chemokine receptor CCR4 and regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5996–6004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vulcano M, Albanesi C, Stoppacciaro A, Bagnati R, D'Amico G, Struyf S, Transidico P, Bonecchi R, Del Prete A, Allavena P, et al.. Dendritic cells as a major source of macrophage-derived chemokine/CCL22 in vitro and in vivo. Eur j immunol. 2001;31:812–22. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3%3c812::AID-IMMU812%3e3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anz D, Rapp M, Eiber S, Koelzer VH, Thaler R, Haubner S, Knott M, Nagel S, Golic M, Wiedemann GM, et al.. Suppression of intratumoral CCL22 by type i interferon inhibits migration of regulatory T cells and blocks cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4483–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mantovani A, Gray PA, Van Damme J, Sozzani S. Macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC). J Leukocyte Biol. 2000;68:400–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao L, Hu X, Zhang J, Huang G, Zhang Y. The role of the CCL22-CCR4 axis in the metastasis of gastric cancer cells into omental milky spots. J Transl Med. 2014;12:267. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0267-1. PMID:25245466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Ye F, Chen H, Lu W, Wan X, Xie X. Human ovarian carcinoma cells generate CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells from peripheral CD4(+)CD25(-) T cells through secreting TGF-beta. Cancer lett. 2007;253:144–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf AM, Wolf D, Steurer M, Gastl G, Gunsilius E, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Increase of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Clin Cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9:606–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma GF, Miao Q, Liu YM, Gao H, Lian JJ, Wang YN, Zeng XQ, Luo TC, Ma LL, Shen ZB, et al.. High FoxP3 expression in tumour cells predicts better survival in gastric cancer and its role in tumour microenvironment. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1552–60. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang YM, Feng AL, Zhou CJ, Liang XH, Mao HT, Deng BP, Yan S, Sun JT, Du LT, Liu J, et al.. Aberrant expression of chemokine receptor CCR4 in human gastric cancer contributes to tumor-induced immunosuppression. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1264–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Yao S, Dann SM, Qin H, Elson CO, Cong Y. ERK differentially regulates Th17- and Treg-cell development and contributes to the pathogenesis of colitis. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:1716–26. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu S, Liu H, Zhang H, Lin C, Li R, Cao Y, He H, Li H, Shen Z, Qin J, et al.. Galectin-8 is associated with recurrence and survival of patients with non-metastatic gastric cancer after surgery. Tumour Biol: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2016;37:12635–42. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5175-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Compton C, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Pettigrew N, Fielding LP. American Joint Committee on Cancer Prognostic Factors Consensus Conference: Colorectal Working Group. Cancer. 2000;88:1739–57. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000401)88:7%3c1739::AID-CNCR30%3e3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merlos-Suarez A, Barriga FM, Jung P, Iglesias M, Cespedes MV, Rossell D, Sevillano M, Hernando-Momblona X, da Silva-Diz V, Muñoz P, et al.. The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:511–24. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeong JA, Hong SH, Gang EJ, Ahn C, Hwang SH, Yang IH, Han H, Kim H. Differential gene expression profiling of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells by DNA microarray. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio). 2005;23:584–93. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalerba P, Sahoo D, Paik S, Guo X, Yothers G, Song N, Wilcox-Fogel N, Forgó E, Rajendran PS, Miranda SP, et al.. CDX2 as a Prognostic Biomarker in Stage II and Stage III Colon Cancer. N Eng J Med. 2016;374:211–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou M, Bracci PM, McCoy LS, Hsuang G, Wiemels JL, Rice T, Zheng S, Kelsey KT, Wrensch MR, Wiencke JK. Serum macrophage-derived chemokine/CCL22 levels are associated with glioma risk, CD4 T cell lymphopenia and survival time. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:826–36. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kryczek I, Wei S, Zhu G, Myers L, Mottram P, Cheng P, Chen L, Coukos G, Zou W. Relationship between B7-H4, regulatory T cells, and patient outcome in human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8900–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumai T, Nagato T, Kobayashi H, Komabayashi Y, Ueda S, Kishibe K, Ohkuri T, Takahara M, Celis E, Harabuchi Y. CCL17 and CCL22/CCR4 signaling is a strong candidate for novel targeted therapy against nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Immunol, Immunother: CII. 2015;64:697–705. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1675-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sektioglu IM, Carretero R, Bulbuc N, Bald T, Tuting T, Rudensky AY, Hämmerling GJ. Basophils Promote Tumor Rejection via Chemotaxis and Infiltration of CD8+ T Cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:291–302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei Y, Wang T, Song H, Tian L, Lyu G, Zhao L, Xue Y. C-C motif chemokine 22 ligand (CCL22) concentrations in sera of gastric cancer patients are related to peritoneal metastasis and predict recurrence within one year after radical gastrectomy. J Sur Res. 2017;211:266–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Wang X, Shen Z, Xu J, Qin J, Sun Y. Infiltration of diametrically polarized macrophages predicts overall survival of patients with gastric cancer after surgical resection. Gastric Cancer: official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2015;18:740–50. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardoso AP, Pinto ML, Pinto AT, Oliveira MI, Pinto MT, Goncalves R, Relvas JB, Figueiredo C, Seruca R, Mantovani A, et al.. Macrophages stimulate gastric and colorectal cancer invasion through EGFR Y(1086), c-Src, Erk1/2 and Akt phosphorylation and smallGTPase activity. Oncogene. 2014;33:2123–33. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M, et al.. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nature medicine. 2004;10:942–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu X, Liu J, Li H, Li W, Wang X, Ma J, Tong Q, Wu K, Wang G. Conversion of intratumoral regulatory T cells by human gastric cancer cells is dependent on transforming growth factor-beta1. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:571–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.22005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merck E, de Saint-Vis B, Scuiller M, Gaillard C, Caux C, Trinchieri G, Bates EE. Fc receptor gamma-chain activation via hOSCAR induces survival and maturation of dendritic cells and modulates Toll-like receptor responses. Blood. 2005;105:3623–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe M, Satoh T, Yamamoto Y, Kanai Y, Karasuyama H, Yokozeki H. Overproduction of IgE induces macrophage-derived chemokine (CCL22) secretion from basophils. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950). 2008;181:5653–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McDermott U, Longley DB, Galligan L, Allen W, Wilson T, Johnston PG. Effect of p53 status and STAT1 on chemotherapy-induced, Fas-mediated apoptosis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8951–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malesci A, Bianchi P, Celesti G, Basso G, Marchesi F, Grizzi F, Di Caro G, Cavalleri T, Rimassa L, Palmqvist R, et al.. Tumor-associated macrophages and response to 5-flourouracil adjuvant therapy in stage III colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1342918. doi: 10.1080/2162402x.2017.1342918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi B, Varambally S. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia (New York, NY). 2017;19:649–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anaya J. OncoLnc: Linking TCGA survival data to mRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs. Peerj Computer Science. 2016;2:e67. doi: 10.7717/peerj-cs.67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y, Liu W, Xu L, Liu H, Zhang W, Zhu Y, Xu J, Gu J. GALNT4 predicts clinical outcome in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2014;192:1534–41. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu XD, Zhang JB, Zhuang PY, Zhu HG, Zhang W, Xiong YQ, Wu WZ, Wang L, Tang ZY, Sun HC. High expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor in peritumoral liver tissue is associated with poor survival after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:2707–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei Y, Lin C, Li H, Xu Z, Wang J, Li R, Liu H, Zhang H, He H, Xu J. CXCL13 expression is prognostic and predictive for postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy benefit in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol, Immunother: CII. 2018;67:261–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2083-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He H, Shen Z, Zhang H, Wang X, Tang Z, Xu J, Sun Y. Clinical significance of polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase-5 (GalNAc-T5) expression in patients with gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2021–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.