Abstract

Background

Mucosal imbalance of interleukin (IL)‐1β and IL‐1 receptor antagonist (Ra) has been reported in the duodenal mucosa of dogs with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). However, the imbalance in the colonic mucosa and its role in duodenitis and colitis in IBD of dogs remain unclear.

Objectives

To measure the expression of IL‐1β and IL‐1Ra proteins in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD, and to determine the effect of IL‐1β on expression of occludin (ocln) mRNA, a tight junction component, in the duodenal and colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD.

Animals

Twelve dogs with IBD and 6 healthy dogs.

Methods

IL‐1β and IL‐1 Ra proteins in the colonic mucosa were quantified by ELISA in 7 of the 12 dogs with IBD. Expression of ocln mRNA in the duodenal and colonic mucosa was examined in the 12 dogs by real‐time PCR.

Results

The ratio of IL‐1β to IL‐1Ra in the colonic mucosa was significantly higher in dogs with IBD than in healthy dogs. The ex vivo experiment determined that IL‐1β suppressed expression of ocln mRNA in the colonic mucosa, but not in the duodenal mucosa, of healthy dogs. Expression of ocln mRNA in the colonic mucosa, but not in the duodenal mucosa, was significantly lower in dogs with IBD than in healthy dogs.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

A relative increase in IL‐1β may attenuate ocln expression, leading to intestinal barrier dysfunction and promotion of intestinal inflammation in the colonic mucosa, but not in the duodenal mucosa, of dogs with IBD.

Keywords: chronic enteropathy, inflammatory cytokine, intestinal barrier dysfunction, tight junction

Abbreviations

- AJs

adherens junctions

- CCECAI

canine chronic enteropathy clinical activity index

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- GI

gastrointestinal

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IECs

intestinal epithelial cells

- IL

interleukin

- NOD

nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain

- OCLN

occludin

- Ra

receptor antagonist

- TBP

TATA‐binding protein

- TJs

tight junctions

- TLRs

toll‐like receptors

- WSAVA

world small animal veterinary association

1. INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in dogs is a group of gastrointestinal (GI) disorders associated with idiopathic, chronic mucosal inflammation in the GI tract.1 Intestinal barrier dysfunction, bacterial flora abnormalities, inappropriate reactions to dietary components or some combination of these are suggested to lead to chronic dysregulation of mucosal immune responses in the small and large intestines of dogs with IBD.2 The pathological and immunological features of IBD in dogs are in part similar to those of IBD in humans, such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. However, the underlying causes for IBD in dogs remain to be fully understood.

Interleukin (IL)‐1β is a proinflammatory cytokine that plays a pivotal role in initiation and amplification of inflammation in various tissues including the intestine. The IL‐1 receptor antagonist (Ra) is an endogenous antagonist of IL‐1α and β and binds to IL‐1 receptor 1, inhibiting biological activity of IL‐1α and β.3 Significant increases in the IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra ratio were reported in intestinal mucosa of the small and large bowel in human patients with Crohn's disease,4 in the colonic mucosa of human patients with ulcerative colitis,4 and in the duodenal mucosa of dogs with IBD.5 These findings suggest that an imbalance of IL‐1β and IL‐1Ra is involved in the pathogenesis of IBD in humans and dogs. Previous studies reported no significant difference in mRNA expression of IL‐1β in the colonic mucosa between dogs with IBD and healthy dogs.6, 7 However, expression and balance of IL‐1β and IL‐1Ra proteins have not been investigated previously in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD.

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) form a physical barrier to luminal bacteria, toxins, and antigens, preventing mucosal inflammation and tissue damage. The intestinal barrier is composed of protein complexes that seal the intercellular junctions of IECs, including tight junctions (TJs), adherens junctions (AJs), and desmosomes.8 The TJs, but not AJs and desmosomes, regulate selective paracellular permeability to ions, solutes, and water. Intestinal permeability was reported to be increased in dogs with IBD,9 suggesting that TJ barrier function was impaired in dogs with IBD. A previous study indicated that protein expression of E‐cadherin, an AJ protein, was significantly decreased in the duodenum of dogs with IBD, but expression of claudin proteins, TJ components, was not significantly different in the duodenum between dogs with IBD and healthy dogs.10 Because intestinal barrier dysfunction has been proposed to be involved in the development of IBD in dogs, expression of other TJ components may be attenuated in the intestines of dogs with IBD.

Interleukin‐1β has been shown to increase TJ permeability in Caco‐2 cells, a human epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line.11 The effect of IL‐1β was at least in part mediated by decreased expression of OCLN, a TJ component. Interleukein‐1B directly suppressed mRNA and protein expression of OCLN in Caco‐2 cells.11 These findings imply that an interaction may occur between IL‐1β and OCLN in the intestine, especially in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD.

Our study aimed to investigate the expression of IL‐1β and IL‐1Ra proteins in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD, and to elucidate the effect of IL‐1β on gene expression of ocln in the duodenal and colonic mucosa of these dogs.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Dogs

Twelve dogs newly diagnosed with IBD at the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Animal Medical Center were included. Inflammatory bowel disease was diagnosed according to previous studies1, 12, 13: (1) chronic GI signs, such as vomiting and diarrhea, over a duration of > 3 weeks; (2) histopathological evidence of inflammation in the duodenal and colonic mucosa in specimens obtained by endoscopic biopsy; (3) exclusion of other causes of chronic GI signs, including metabolic disease, infection, parasitic disease, pancreatic insufficiency, hepatic disease, renal disease, and alimentary lymphoma; (4) ruling out antibiotic‐responsive and food‐responsive enteropathies by appropriate antibiotic and dietary trials; and, (5) partial or complete response to PO administration of prednisolone (Pfizer, Tokyo, Japan; 0.5‐2.0 mg/kg q24h). Clinical severity of 12 dogs with IBD was scored according to the canine chronic enteropathy clinical activity index (CCECAI).14

Six healthy intact male beagles maintained for research purposes were used as a control group. The median age of the control dogs was 3.8 years (range, 1.2–6.4 years) and the median body weight was 11.1 kg (range, 10.1–11.6 kg). Dogs were housed in individual cages and fed a commercial diet (Science Diet Adult, Hill's‐Colgate Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) once daily. Water was provided ad libitum.

Dogs with IBD and healthy dogs did not receive any drugs including antibiotics, antidiarrheals, antiflatulents, and immunosuppressive agents such as glucocorticoids for at least 1 week before sample collection. All dogs with IBD had active clinical signs at the time of sample collection.

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology.

2.2. Collection of duodenal and colonic mucosa from dogs

The duodenal and colonic mucosal samples were obtained from dogs with IBD and healthy dogs by endoscopic biopsy forceps under general anesthesia. Dogs were prepared for endoscopy by withholding food for at least 24 hours. A colon cleansing using saline was conducted under anesthesia. More than 6 tissue specimens were obtained from each region. The duodenal and colonic biopsy specimens were subjected to histopathological examination after fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin. All duodenal and colonic histologic specimens were independently reviewed by a single board‐certified veterinary anatomic pathologist (HK). When the quality of the samples was evaluated, all samples were judged to be of marginal or adequate quality and none of the samples examined was inadequate according to previously published criteria.15 All samples were examined according to the guideline of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) international GI standardization group.1 For duodenal and colonic samples, 9 representative morphologic changes (villous stunting, epithelial injury, crypt distension, lacteal dilatation, mucosal fibrosis, intraepithelial lymphocytes, lamina propria lymphocytes/plasma cells, lamina propria eosinophils, and lamina propria neutrophils) and 8 representative morphologic changes (surface epithelial injury, crypt hyperplasia, crypt dilatation and distortion, mucosal fibrosis/atrophy, lamina propria lymphocytes/plasma cells, lamina propria eosinophils, lamina propria neutrophils and lamina propria macrophages) were assessed, respectively. The presence and severity of each pathologic change was graded and scored 0–3, where 0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = marked in accordance with a previous report.16 The total histologic severity scores were obtained from the sum of each histologic variable score. When intraspecimen variation from 1 animal was observed, more severely affected lesions were evaluated. In healthy beagles, the median WSAVA scores in the duodenum and in the colon were 2.5 (range, 2–3) and 0 (range, 0–1), respectively, similar to the result of a previous study.17 Portions of the duodenal and colonic biopsy samples were stored at −80°C until protein extraction, and the remaining portions were stored in RNAlater Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) according to the manufacturer's instructions for preservation until RNA extraction.

2.3. Ex vivo culture of the duodenal and colonic biopsy specimens

The duodenal and colonic biopsy specimens were obtained from 4 of the 6 healthy dogs during endoscopy. Immediately after collection, the endoscopic biopsy specimens were washed 5 times with ice‐cold Roswell Park Memorial Institute‐1640 medium (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with l‐glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (Biowest, Nuaillé, France), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, Osaka, Japan). After washing, each sample was cut into 2 pieces and seeded in a 24‐well flat‐bottomed plate; 1 was cultured with medium alone as a control and the other was incubated with medium containing 10 ng/mL of canine recombinant IL‐1β (R&D Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota) at 37°C for 24 hours under 5% CO2. The concentration of IL‐1β was determined according to a previous study,11 which reflected inflammatory conditions in humans18 and a rabbit model of colitis.19 After incubation, the samples were immediately preserved in RNAlater Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) for RNA extraction.

2.4. ELISA

The colonic biopsy specimens from 7 of the 12 dogs with IBD and 6 healthy dogs were homogenized in 300 μL of lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (EzRIPA Lysis kit, ATTO, Tokyo, Japan). After centrifugation, supernatants were preserved at −80°C until analysis. Total protein concentrations were determined using a commercial kit (TaKaRa BCA Protein Assay Kit, Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). Based on the results of previous studies,5, 20 cytokine concentrations were measured using commercial ELISA kits specific for canine IL‐1β (Canine IL‐1beta ELISA kit, RayBiotech, Inc, Norcross, Georgia and IL‐1Ra (ELISA Kit for IL 1 Receptor Antagonist, Cloud‐Clone Corp, Katy, Texas). The cytokine concentrations were normalized to the total protein concentration in each sample. The IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra ratio was calculated by dividing the amount of IL‐1β by the amount of IL‐1Ra in each dog.

2.5. Real‐time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the duodenal and colonic specimens from 12 dogs with IBD and 6 healthy dogs using NucleoSpin RNA (Takara Bio) and reverse‐transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara Bio). The cDNA samples were subjected to real‐time PCR analysis as described previously.21 Primers for real‐time PCR (Supporting Information Table S1) were designed by a Perfect Real Time support system (Takara Bio) and according to a previous report.12 As reference genes, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh), TATA‐binding protein (tbp), and succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit A were selected for the duodenal mucosa, and gapdh, tbp, and hydroxymethylbilane synthase were chosen for the colonic mucosa, as described previously.12 The relative mRNA expression of a target gene was determined by the 2–ΔCt method, wherein each result is presented as an n‐fold difference relative to the geometric mean of the 3 reference genes.22

2.6. Statistical analysis

The normality of all data was analyzed by the Shapiro‐Wilk test. Data between 2 groups were compared by a paired or unpaired student's t test, the Mann‐Whitney U test, or the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test, depending on normality. The correlations between 2 groups were evaluated by Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. Statistical analyses were performed using BellCurve for Excel (Social Survey Research Information Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) software. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical and histopathological characteristics of dogs with IBD

The dog breeds included Pembroke Welsh Corgi (n = 3), American Pit Bull Terrier (n = 1), Border Collie (n = 1), Brussels Griffon (n = 1), Maltese (n = 1), Papillon (n = 1), Pug (n = 1), Shiba Inu (n = 1), Toy Poodle (n = 1), and Mixed Breed (n = 1). The dogs consisted of 6 castrated males, 4 intact males, 1 spayed female, and 1 intact female. The median age of the dogs was 9.2 years (range, 1.8–14.1 years). The median weight of the dogs was 6.9 kg (range, 3.3–19.4 kg). All 12 dogs had histopathological evidence of both lymphoplasmacytic duodenitis and colitis. All dogs showed both small and large bowel diarrhea with or without vomiting. The median CCECAI score was 7 (range, 3–14). The median WSAVA scores in the duodenum and in the colon were 10.5 (range, 6–17) and 4 (range, 2–9), respectively. No significant correlations were detected between the CCECAI score and the WSAVA score in the duodenal mucosa (r s = 0.05, P = .88) and in the colonic mucosa (r s = −0.57, P = .05) of dogs with IBD, similar to the previous findings in dogs with chronic enteropathies including IBD and food responsive diarrhea.23, 24, 25

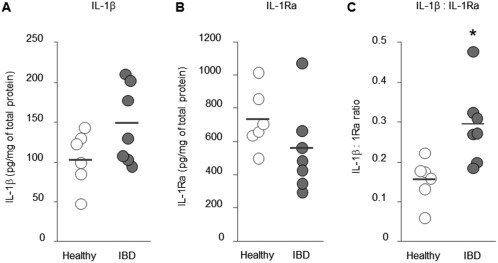

3.2. Expression of IL‐1β and IL‐1Ra proteins in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD and healthy dogs

Expression of an IL‐1β protein in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD was not significantly different from that of healthy dogs (P = .10; Figure 1A). Similarly, expression of an IL‐1Ra protein in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD was not significantly different from that of healthy dogs (P = .20; Figure 1B). However, the IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra in the colonic mucosa was significantly higher in dogs with IBD than in healthy dogs (P = .01; Figure 1C). No significant correlation was detected between the CCECAI score and the IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra in dogs with IBD (r s = 0.04, P = .94).

Figure 1.

Expression of IL‐1β and IL‐1 Ra in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD. Protein concentrations of IL‐1β (A) and IL‐1Ra (B) were determined by ELISA in healthy dogs (n = 6) and dogs with IBD (n = 7), and normalized to the total protein concentration in each dog. The IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra ratio (C) was calculated by dividing the amount of IL‐1β by that of IL‐1Ra in each dog. The horizontal lines in each group represent the mean value. Data between 2 groups were compared by the unpaired t test (A, B, and C). *P < .05

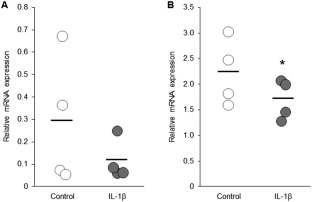

3.3. Effect of IL‐1β on expression of ocln mRNA in the ex vivo cultured duodenal and colonic mucosae

Expression of ocln mRNA in IL‐β‐stimulated duodenal biopsy specimens was not significantly different from that of nonstimulated duodenal biopsy specimens (P = .43; Figure 2A). In contrast, expression of ocln mRNA was significantly lower in IL‐β‐stimulated colonic biopsy specimens than in nonstimulated colonic biopsy specimens (P = .038; Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Relative mRNA expression of ocln in the ex vivo cultured duodenal and colonic mucosa of healthy dogs. The duodenal and colonic mucosa were obtained from healthy dogs (n = 4) by endoscopy. Each sample was cut into 2 pieces; 1 was cultured with medium alone as a control and the other was incubated with medium containing canine IL‐1β (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Expression levels of ocln mRNA in the duodenal (A) and the colonic (B) mucosa were quantified by real‐time PCR. The horizontal lines in each group represent the mean value. Data between control and IL‐β groups were compared by the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test (A) or the paired t test (B). *P < .05

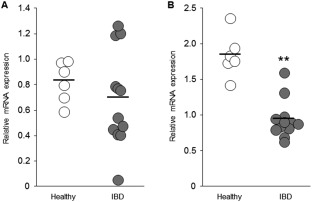

3.4. Expression of ocln mRNA in the duodenal and colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD and healthy dogs

Expression of ocln mRNA in the duodenal mucosa of dogs with IBD was not significantly different from that of healthy dogs (P = .47; Figure 3A). In contrast, expression of ocln mRNA in the colonic mucosa was significantly lower in dogs with IBD than in healthy dogs (P = .001; Figure 3B). No significant correlations were detected between the CCECAI score and expression level of ocln mRNA in the duodenal mucosa (r s = −0.05, P = .88) and colonic mucosa (r s = −0.47, P = .13) of dogs with IBD. In addition, no significant correlations were detected between the WSAVA score and expression level of ocln mRNA in the duodenal mucosa (r s = −0.36, P = .25) and colonic mucosa (r s = −0.06, P = .84) of dogs with IBD.

Figure 3.

Relative mRNA expression of ocln in the duodenal and colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD. Expression levels of ocln mRNA in the duodenal (A) and the colonic (B) mucosa were quantified by real‐time PCR in healthy dogs (n = 6) and dogs with IBD (n = 12). The horizontal lines in each group represent the mean value. Data between 2 groups were compared by the unpaired t test (a) or the Mann‐Whitney U test (B). **P < .01

4. DISCUSSION

Our study clearly showed an increase in the IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra ratio in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD. The ex vivo experiment indicated that IL‐1β suppressed gene expression of ocln in the colonic mucosa, but not in the duodenal mucosa, of healthy dogs. In addition, expression of ocln mRNA was significantly lower in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD than in healthy dogs, but expression in the duodenal mucosa was not significantly different between dogs with IBD and healthy dogs. These findings suggest that IL‐1β has different roles in the development of duodenitis and colitis in dogs with IBD. A relative increase in IL‐1β may attenuate ocln expression, thereby leading to intestinal barrier dysfunction and promotion of intestinal inflammation in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD. In contrast, it remains unclear how IL‐1β contributes to the development of duodenitis in dogs with IBD.

Several studies have investigated cytokine profiles in the duodenal and colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD at mRNA or protein levels, but consistent results have not yet been obtained.7, 26, 27, 28 A previous study reported absolute and relative increases in IL‐1β in the duodenal mucosa of dogs with IBD.5 In our study, we identified an increase in the IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra ratio in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD. These results indicate that increased expression of IL‐1β plays a key role in the development of duodenitis and colitis in dogs with IBD.

Intestinal expression of OCLN was reported to be markedly decreased in the ileum, cecum, jejunum, and colon in patients with Crohn's disease, and in the cecum, colon, and rectum in patients with ulcerative colitis.29, 30 In addition, both mRNA concentrations of ocln and protein concentrations of OCLN were shown to be decreased in the intestine of patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.29 It is therefore conceivable that mRNA concentrations of ocln are associated with protein concentrations of OCLN in the intestine. We found for the first time that mRNA expression of ocln was significantly decreased in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD. In contrast, a significant decrease of ocln mRNA was not detected in the duodenal mucosa of dogs with IBD, possibly because of large variations in mRNA expression. Occludin was shown to maintain intestinal TJ permeability by regulating macromolecule flux across the intestinal epithelial barrier.31 Thus, a decrease in mRNA expression of ocln may be associated with intestinal barrier dysfunction and increased intestinal permeability in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD.

We attempted to determine a possible interaction between IL‐1β and OCLN in the duodenal and colonic biopsy specimens. The ex vivo experiment indicated that IL‐1β suppressed mRNA expression of ocln in the colonic biopsy specimens of healthy dogs. However, it did not significantly decrease mRNA expression of ocln in the duodenal biopsy specimens. It therefore is conceivable that IL‐1β differentially regulates intestinal inflammation in the duodenum and in the colon of dogs with IBD. In the colon, IL‐1β may lead to intestinal barrier dysfunction by decreasing OCLN expression. In contrast, the mechanisms by which IL‐1β contributes to the development of duodenitis were not determined in our study.

Interleukin‐1β in the intestine is mainly produced by lamina propria macrophages32, 33, 34 in response to the activation of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as toll‐like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain (NOD)‐like receptors.35, 36 Gut microbiota play an important role in the activation of PRRs in the intestine.35, 36 Intestinal bacteria penetrate the impaired intestinal epithelial barrier, activating inflammatory cells, including macrophages, to produce various cytokines in the lamina propria.8, 35, 36 In dogs with IBD, expression of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 mRNA in the duodenal and colonic mucosa and NOD2 mRNA in the colonic mucosa was shown to be higher than in healthy dogs.37, 38 Gut microbiota are present more abundantly in the colon than in the duodenum.39 Thus, activation of PRRs by gut microbiota may be more important for IL‐1β production in the colon as compared with the duodenum in dogs with IBD. Further studies would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

We did not observe significant correlations between the CCECAI score and the IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra ratio or the expression level of ocln mRNA in the colonic mucosa. A previous study showed that the IL‐1β : IL‐1Ra ratio in the duodenal mucosa correlated with the CCECAI score in dogs with IBD.5 Our results may be a consequence of the fact that the dogs we analyzed had colitis as well as duodenitis.

Our study had 2 major limitations. One was that the mRNA expression of ocln only was examined in the duodenal and colonic mucosa of a small number of dogs with IBD. Further studies are required to clarify the expression and distribution of OCLN at protein level in the duodenal and the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD, using a larger sample size. In addition, it is also necessary to elucidate whether IL‐1β‐mediated attenuation of OCLN expression increases intestinal barrier permeability in dogs with IBD. Another limitation was that age‐ and breed‐matched healthy dogs were not used as a control group. It is possible that this might have affected the result, which needs to be resolved in further studies.

In conclusion, we found a relative increase in IL‐1β protein and a decrease in mRNA expression of ocln in the colonic mucosa of dogs with IBD, as compared with healthy dogs. We also clarified the suppressive effect of IL‐1β on mRNA expression of ocln in the colonic mucosa, but not in the duodenal mucosa. Our findings highlighted the importance of IL‐1β and OCLN in the development of colitis in dogs with IBD. Additional studies are necessary to further characterize the relationship between inflammation and barrier dysfunction in the intestines of dogs with IBD.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

IACUC approval from Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Number: 17K08099) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Ogawa M, Osada H, Hasegawa A, et al. Effect of interleukin‐1β on occludin mRNA expression in the duodenal and colonic mucosa of dogs with inflammatory bowel disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32:1019–1025. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15117

Funding information Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grant/Award Number: 17K08099

This work was completed in the Cooperative Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Fuchu, Tokyo, Japan and the Laboratory of Veterinary Pathology, Department of Veterinary Medicine, College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, Fujisawa, Kanagawa, Japan. This study was orally presented at Asian Meeting of Animal Medicine Specialties 2017 in Daegu, Korea.

REFERENCES

- 1. Washabau RJ, Day MJ, Willard MD, et al. Endoscopic, biopsy, and histopathologic guidelines for the evaluation of gastrointestinal inflammation in companion animals. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:10–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. German AJ, Hall EJ, Day MJ. Chronic intestinal inflammation and intestinal disease in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2003;17:8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dinarello CA. Biologic basis for interleukin‐1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Casini‐Raggi V, Kam L, Chong YJ, Fiocchi C, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F. Mucosal imbalance of IL‐1 and IL‐1 receptor antagonist in inflammatory bowel disease. A novel mechanism of chronic intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 1995;154:2434–2440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maeda S, Ohno K, Nakamura K, et al. Mucosal imbalance of interleukin‐1β and interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist in canine inflammatory bowel disease. Vet J. 2012;194:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jergens AE, Sonea IM, O'Connor AM, et al. Intestinal cytokine mRNA expression in canine inflammatory bowel disease: a meta‐analysis with critical appraisal. Comp Med. 2009;59:153–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tamura Y, Ohta H, Yokoyama N, et al. Evaluation of selected cytokine gene expression in colonic mucosa from dogs with idiopathic lymphocytic‐plasmacytic colitis. J Vet Med Sci. 2014;76:1407–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suzuki T. Regulation of intestinal epithelial permeability by tight junctions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:631–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kobayashi S, Ohno K, Uetsuka K, et al. Measurement of intestinal mucosal permeability in dogs with lymphocytic‐plasmacytic enteritis. J Vet Med Sci. 2007;69:745–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ohta H, Sunden Y, Yokoyama N, et al. Expression of apical junction complex proteins in duodenal mucosa of dogs with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Vet Res. 2014;75:746–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al‐Sadi RM, Ma TY. IL‐1beta causes an increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J Immunol. 2007;178:4641–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Osada H, Ogawa M, Hasegawa A, et al. Expression of epithelial cell‐derived cytokine genes in the duodenal and colonic mucosae of dogs with chronic enteropathy. J Vet Med Sci. 2017;79:393–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Simpson KW, Jergens AE. Pitfalls and progress in the diagnosis and management of canine inflammatory bowel disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2011;41:381–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Allenspach K, Wieland B, Gröne A, Gaschen F. Chronic enteropathies in dogs: Evaluation of risk factors for negative outcome. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Willard MD, Mansell J, Fosgate GT, et al. Effect of sample quality on the sensitivity of endoscopic biopsy for detecting gastric and duodenal lesions in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:1084–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jergens AE, Evans RB, Ackermann M, et al. Design of a simplified histopathologic model for gastrointestinal inflammation in dogs. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:946–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walker D, Knuchel‐Takano A, McCutchan A, et al. A comprehensive pathological survey of duodenal biopsies from dogs with diet‐responsive chronic enteropathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:862–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iwamoto GK, Monick MM, Burmeister LF, Hunninghake GW. Interleukin 1 release by human alveolar macrophages and blood monocytes. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:C1012–C1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cominelli F, Nast CC, Clark BD, et al. Interleukin 1 (IL‐1) gene expression, synthesis, and effect of specific IL‐1 receptor blockade in rabbit immune complex colitis. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:972–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Safra N, Hitchens PL, Maverakis E, et al. Serum levels of innate immunity cytokines are elevated in dogs with metaphyseal osteopathy (hypertrophic osteodystrophy) during active disease and remission. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2016;179:32–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ohmori K, Nishikawa S, Oku K, et al. Circadian rhythms and the effect of glucocorticoids on expression of the clock gene period1 in canine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Vet J. 2013;196:402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, et al. Accurate normalization of real‐time quantitative RT‐PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmitz S, Glanemann B, Garden OA, et al. A prospective, randomized, blinded, placebo‐controlled pilot study on the effect of Enterococcus faecium on clinical activity and intestinal gene expression in canine food‐responsive chronic enteropathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:533–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Procoli F, Mõtsküla PF, Keyte SV, Priestnall S, Allenspach K. Comparison of histopathologic findings in duodenal and ileal endoscopic biopsies in dogs with chronic small intestinal enteropathies. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schreiner NM, Gaschen F, Gröne A, Sauter SN, Allenspach K. Clinical signs, histology, and CD3‐positive cells before and after treatment of dogs with chronic enteropathies. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:1079–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peters IR, Helps CR, Calvert EL, Hall EJ, Day MJ. Cytokine mRNA quantification in duodenal mucosa from dogs with chronic enteropathies by real‐time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:644–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schmitz S, Garden OA, Werling D, Allenspach K. Gene expression of selected signature cytokines of T cell subsets in duodenal tissues of dogs with and without inflammatory bowel disease. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2012;146:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ohta H, Takada K, Sunden Y, et al. CD4+ T cell cytokine gene and protein expression in duodenal mucosa of dogs with inflammatory bowel disease. J Vet Med Sci. 2014;76:409–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gassler N, Rohr C, Schneider A, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with changes of enterocytic junctions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G216–G228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D, et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn's disease. Gut. 2007;56:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Al‐Sadi R, Khatib K, Guo S, Ye D, Youssef M, Ma T. Occludin regulates macromolecule flux across the intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G105410–G1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cappello M, Keshav S, Prince C, Jewell DP, Gordon S. Detection of mRNAs for macrophage products in inflammatory bowel disease by in situ hybridisation. Gut. 1992;33:1214–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mahida YR, Wu K, Jewell DP. Enhanced production of interleukin 1‐beta by mononuclear cells isolated from mucosa with active ulcerative colitis of Crohn's disease. Gut. 1989;30:835–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Youngman KR, Simon PL, West GA, et al. Localization of intestinal interleukin 1 activity and protein and gene expression to lamina propria cells. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ignacio A, Morales CI, Câmara NO, Almeida RR. Innate sensing of the gut microbiota: Modulation of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2016;7:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zaki MH, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. The Nlrp3 inflammasome: contributions to intestinal homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burgener IA, König A, Allenspach K, et al. Upregulation of toll‐like receptors in chronic enteropathies in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:553–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Okanishi H, Hayashi K, Sakamoto Y, et al. NOD2 mRNA expression and NFkappaB activation in dogs with lymphocytic plasmacytic colitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Supporting Information