Abstract

Background

Following the phase-out of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), organophosphate esters (OPEs) have been increasingly used in consumer products and building materials for their flame retardant and plasticizing properties. As a result, human exposure to these chemicals is widespread as evidenced by common detection of their metabolites in urine. However, little is known about the major exposure pathways, or factors that influence children’s exposure to OPEs. Furthermore, little data is available on exposure to the novel aryl OPEs.

Objectives

To examine predictors of children’s internal exposure, we assessed relationships between OPEs in house dust and on hand wipes and levels of their corresponding metabolites in paired urine samples (n = 181). We also examined associations between urinary metabolites and potential covariates, including child’s age and sex, mother’s educational attainment and race, and average outdoor air temperature.

Methods

Children aged 3 to 6 years provided urine and hand wipe samples. Mothers or legal guardians completed questionnaires, and a house dust sample was taken from the main living area during home visits. Alkyl chlorinated and aryl OPEs were measured in dust and hand wipes, and composite urine samples were analyzed for several metabolites.

Results

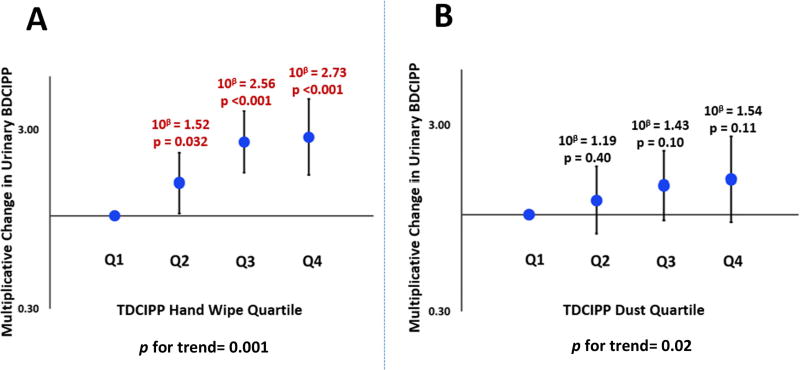

Tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP), tris(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCIPP), tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TDCIPP), 2-ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate (EHDPHP), triphenyl phosphate (TPHP), and 2-isopropylphenyl diphenyl phosphate (2IPPDPP) were detected frequently in hand wipes and dust (> 80%), indicating that these compounds are near-ubiquitous in indoor environments. Additionally, bis(1-chloro-2-propyl) 1-hydroxy-2-propyl phosphate (BCIPHIPP), bis(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (BDCIPP), diphenyl phosphate (DPHP), mono-isopropyl phenyl phosphate (ip-PPP), and mono-tert-butyl phenyl phosphate (tb-PPP) were detected in >94% of tested urine samples, signifying that TESIE participants were widely exposed to OPEs. Contrary to PBDEs, house dust OPE concentrations were generally not correlated with urinary OPE metabolite levels; however, hand wipe levels of OPEs were associated with internal dose. For example, children with the highest mass of TDCIPP on hand wipes had BDCIPP levels that were 2.73 times those of participants with the lowest levels (95% CI: 1.67, 4.48, p <0.0001). Of the variables examined, hand wipe level was the most consistent and strongest predictor of OPE urinary metabolite concentrations. Outdoor air temperature was also a significant predictor of urinary BDCIPP concentrations, with a 1°C increase in temperature corresponding to a 4% increase in urinary BDCIPP (p<0.0001).

Conclusions

OPE exposures are highly prevalent, and data provided herein further substantiate hand-to-mouth contact and dermal absorption as important pathways of OPE exposure, especially for young children.

Introduction

Flame retardants (FRs) are chemicals added to consumer products and building materials to slow or prevent their combustion. Historically, polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) were used to treat a wide array of products; however, following their phase-out in the early 2000s, organophosphate esters (OPEs) have been increasingly used to meet residential and commercial flammability standards (Cooper et al., 2016). In addition to flame retardant applications in furniture, electronics, and insulation, OPEs are heavily used as plasticizers. In fact, it is estimated that the global market for OPEs will grow from $1.3 billion in 2014 to $1.6 billion in 2019, with plastic applications accounting for the majority of this growth (Green, 2015). For aryl OPEs, this projected increase will likely be compounded by the recent Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) ruling banning the use of organohalogen flame retardants in several consumer product categories in the United States (Kaye, 2017). Aryl OPEs are anticipatory substitutes for the banned organohalogen flame retardants, and are already used extensively in commerce (Phillips et al., 2017).

Because OPEs are applied to products in an additive rather than reactive manner, they can migrate out of the treated product over time, leading to human exposure (Wensing et al., 2005). Widespread use of OPEs has led to their ubiquitous detection in air and in dust in a variety of indoor environments (Bergh et al., 2011; Hoffman et al., 2015; Stapleton et al., 2009). Many recent studies have indicated human exposure to OPEs is near ubiquitous with frequent detection of OPE metabolites in urine (Hammel et al., 2016; Hoffman et al., 2017; Ospina et al., 2018). Other studies have highlighted the potential for OPEs to impact human health as endocrine disruptors, reproductive-, developmental-, and neuro-toxicants (Behl et al., 2016; Noyes et al., 2015; Preston et al., 2017; Schang et al., 2016; Slotkin et al., 2017). This is concerning for young children who often have higher FR exposures compared to other age groups and are at a particularly vulnerable time in development (Butt et al., 2014; Hoffman et al., 2017b; Sahlström et al., 2014; Van den Eede et al., 2015).

Previous studies have indicated that inadvertent ingestion of house dust is the largest contributor of exposure for PBDEs in North American populations, while diet is thought to be a primary source of exposure in European populations (Bramwell et al., 2017; Jones-Otazo et al., 2005; Lorber, 2008; Roosens et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2007). Correspondingly, measures of FRs in house dust have often been used as a paradigm for estimating exposure. More recently, hand wipes have been used to characterize human exposure to FRs, and have been shown to be have potential as an exposure metric for OPEs in particular (Hoffman et al., 2015; Stapleton et al., 2014; Watkins et al., 2011). In addition, in vitro findings demonstrate that dermal absorption likely plays a role in the exposure pathway for OPEs (Abou-Elwafa Abdallah et al., 2016; Frederiksen et al., 2018).

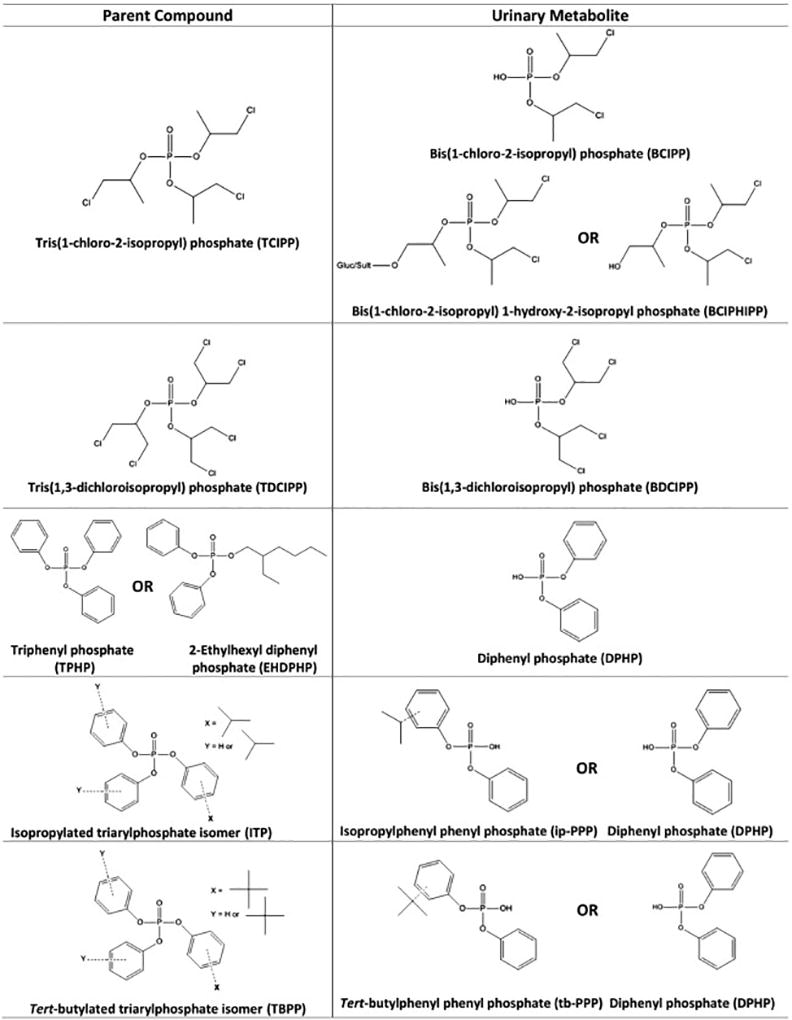

Despite ongoing and potentially increasing human exposure to OPEs, very few studies have investigated factors that influence OPE exposure in children, especially for the novel, aryl OPEs. The Toddlers’ Exposure to SVOCs in the Indoor Environment (TESIE) study allows for an ideal opportunity to address some of these data gaps. Approximately 200 children, aged 3 to 6 years, participated in the TESIE study, with home visits conducted from 2014 to 2016. The current study utilized paired samples of dust, hand wipes, and urine collected from TESIE participants during home visits to assess determinants of OPE exposure. Figure 1 shows the structures of the parent compounds and their corresponding known metabolites discussed in this paper; structures are not included for tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBOEP) and tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP) for which metabolites were not analyzed, as well as for individual isopropylated triarylphosphate (ITP) and tert-butylated triarylphosphate (TBPP) isomers. Relationships between urinary OPE metabolite levels and dust concentrations, hand wipe levels, demographic variables (e.g. age and mother’s race/ethnicity), and average outdoor temperature were examined to determine their potential impact on children’s exposure to OPEs.

Figure 1.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Mothers recruited as part of the Newborn Epigenetics STudy (NEST), a prospective pregnancy cohort study based in central North Carolina, were re-contacted and their children were invited to participate in the Toddler’s Exposure to SVOCs in the Indoor Environment (TESIE) study (Hoyo et al., 2011; Hoffman et al. 2018). Hoffman et al. 2018 provides a detail comparison of families participating in both NEST and the TESIE study. Briefly, children (n=203) from 190 homes in were recruited and participated in the TESIE study between September 2014 and April 2016 when children were approximately 3–6 years of age. The objective of this study was to measure prenatal and postnatal exposure to SVOCs and examine associations with health outcomes. The study population is described in Table S1 and more extensively in Hoffman et al. (2018). All study protocols and related materials were approved by the Duke Medicine Institutional Review Board for Clinical Investigations. Legal guardians provided informed consent prior to the collection of samples and questionnaire data.

Sample Collection

Research personnel visited the homes of enrolled participants to conduct questionnaires with legal guardians and collect samples from the home and children. Families were instructed not to vacuum their homes for two days prior to the scheduled visit. During the home visit, a hand wipe sample was collected from each child using pre-cleaned cotton twill wipes (4×4 in., MG Chemicals) wrapped in aluminum foil, similar to previously described methods (Stapleton et al., 2008). A gloved researcher collected each sample by soaking the twill wipe with 3 mL isopropyl alcohol and wiping the entire surface area of both of the child’s hands from wrists to fingertips, including between each of their fingers. Hand wipes were then rewrapped in foil and stored at −20°C until analysis. To collect a house dust sample, the entire exposed floor area of the main living area was vacuumed using a Eureka Mighty Mite vacuum fitted with a cellulose thimble within the hose attachment (Stapleton et al., 2012). For each visit, an identical vacuum was used to collect the samples. The hose attachment was cleaned with soap and water and solvent rinsed in between each home visit to prevent cross-contamination. In our sampling design, dust passes straight from the hose attachment into the thimble during collection. As such, we do not anticipate OPE contamination from the vacuum itself. Each thimble was wrapped in aluminum foil and stored at −20°C until analysis.

Additionally, during the home visit, families were given collection kits for urine samples. Three spot urine samples were collected from each child by their parent during a 48-hour period. Urine samples were stored frozen in the families’ homes during the sampling period. After the three individual samples were collected, the urine was transported to our research laboratory on ice and stored at −20°C. Prior to analysis, the samples were thawed, and equal volumes of each urine sample were pooled to form a composite.

During the home visits, the week of sample collection was recorded. From this week, average outdoor temperature was retrieved from the National Weather Service website to examine the potential impact of temperature on exposure pathways.

Hand Wipe Extraction

Hand wipes were extracted and analyzed similar to methods developed by Van den Eede at al. (2012). Wipes were spiked with the following internal standards: d15-tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (d15-TDCIPP; 45.6 ng) and 13C-triphenyl phosphate (13C-TPHP; 38.0 ng). Hand wipes were extracted in 1:1 dichloromethane:hexane (v/v) by sonication, and extracts were concentrated to ~1 mL using a SpeedVac™ Concentrator. Extracts were cleaned using Florisil® solid-phase extraction cartridges (Supel-clean ENVI-Florisil, 6 mL, 500 mg; Supelco), eluting the F2 fraction containing OPEs with 10 mL ethyl acetate. F1 fractions eluted using 6 mL hexane and F3 fractions eluted using 6 mL methanol were also collected and used for analyses not described in this paper. F2 fractions were concentrated to ~1 mL using a SpeedVac™ concentrator and were reconstituted in hexane prior to GC/MS analysis. Recovery of internal standards was assessed using d9-tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (d9-TCEP; 164.8 ng) for d15-TDCIPP, and d15-triphenyl phosphate (d15-TPHP; 164.8 ng) for 13C-TPHP. Field blanks (n=14) were analyzed in each batch for quality assurance and quality control (Table S2).

Dust Extraction

Dust samples were sieved to <500 microns prior to extraction. Dust samples were extracted in the same manner as hand wipe samples, with minor adjustments. Dust extracts were split, reserving ~25% for cell-based toxicity assays, 25% for non-targeted analysis, and the remaining 50% for targeted analyses described here. For this reason, internal standards (d15-TDCIPP; 173.4 ng and 13C-TPHP; 173.4 ng) were spiked following extraction. Laboratory blanks (n=6) and house dust standard reference material (n=5; SRM 2585 National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Gaithersburg, MD) were analyzed in each batch for quality assurance and quality control (Table S2). Measurements of OPEs (TCEP, TCIPP, TDCIPP, and TPHP) in SRM 2585 were 86–132% of the values reported in published literature (Van den Eede et al., 2012, 2011) and were deemed acceptable for quality assurance and quality control purposes.

Urine Extraction

Prior to analysis, specific gravity (SG) was measured for each pooled urine sample using a digital handheld refractometer. The measured concentration of all urinary metabolites was corrected for dilution prior to statistical analyses, as recommended by Boeniger et al. (1993). Urine samples were analyzed for bis(2-chloro-isopropyl) phosphate (BCIPP), bis(1-chloro-2-propyl) 1-hydroxy-2-propyl phosphate (BCIPHIPP), bis(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (BDCIPP), diphenyl phosphate (DPHP), mono-isopropyl phenyl phosphate (ip-PPP), and mono-tert-butyl phenyl phosphate (tb-PPP) using previously described methods (Butt et al., 2016; Cooper et al., 2011; Van den Eede et al., 2015). Briefly, 5.0 mL of each pooled urine sample was spiked with internal standards d10-BDCIPP (10 ng), d10-DPHP (8.8 ng), and d15-TDCIPP (35 ng). Urine samples were incubated overnight at 37°C with a 1 M sodium acetate buffer solution (pH 5) and an enzyme solution containing β-glucoronidase and sulfatase. Metabolites were extracted using a mixed-mode anion-exchange solid-phase extraction and analyzed using electrospray ionization liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (Agilent Technologies Model 6410). Recovery of the internal standards were assessed using 13C2-DPHP (25 ng) for all three internal standards. Lab blanks (n=11) and a urine standard reference material (n=6; SRM 3673; NIST, Gaithersburg, MD) were analyzed alongside samples for quality assurance and control (Table S2). Measurements in SRM 3673 were 0.59 ± 0.10, 0.31 ± 0.001, 1.11 ± 0.27, 0.55 ± 0.05, and 2.59 ± 0.39 ng/mL for BCIPP, BCIPHIPP, BDCIPP, DPHP, and ip-PPP, respectively. These values are similar to levels reported by Hammel et al. and A. Covaci’s group (University of Antwerp, Belgium) during an interlab comparison exercise with this SRM (Covaci, 2015; Hammel et al., 2016). In a small number of dust samples (<10%), the responses for TCPP, TDCPP, TBOEP and TPHP were off the calibration curve, and were estimated using a linear regression analysis for points above the curve. However, TBOEP responses in dust were above the calibration curve in 29% of dust samples and 49% of hand wipe samples, and thus the geometric mean and percentile distributions should be interpreted with some caution.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for analytes detected in >50% of samples. Method detection limits (MDLs) were calculated using three times the standard deviation of the average lab blanks for dust and urine samples, and field blanks for the hand wipes. MDLs were normalized to the average mass of dust extracted (0.059 mg) or volume of urine extracted (5 mL), accordingly. Values that were less than MDL were replaced with MDL/2 (Antweiler and Taylor, 2008). Preliminary analyses indicated that OPE concentrations in dust and on hand wipes, as well as the OPE metabolite concentrations in urine were log-normally distributed. Accordingly, Spearman correlations were used to assess relationships within and between matrices. These were conducted for both unadjusted and specific gravity corrected urinary metabolite levels; since these coefficients were not differentiable, specific gravity corrected results are presented here.

Generalized estimating equations were used to examine predictors of log10-transformed urinary OPE metabolite concentrations, as these models took into account residual within-family correlations potentially introduced by the inclusion of siblings in the models. Variables examined included child’s sex, age, mother’s race/ethnicity, mother’s education level at the time of birth (a proxy for socioeconomic status or SES), average outdoor temperature (continuous variable), dust concentration, and hand wipe level. As suggested by O’Brien et al. (2015), analyses were also performed using specific gravity as a covariate; results were indistinguishable from those obtained without including specific gravity as a covariate (data not shown). Education was dichotomized as having earned a four-year college degree (bachelor’s or graduate) or not. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic. The race/ethnicity of three participants was classified as “Other” and they were excluded from analyses. Child’s age was dichotomized at the median (54 months). Hand wipe and dust levels were categorized as quartiles, except for hand wipe TBOEP and B4tBPPP and dust 24DIPPDPP and 4IPPDPP, which were categorized as either tertiles or detected/not detected due to lower detection frequencies for these compounds. When assessed in a univariate analysis, hand washing frequency did not significantly impact OPE levels on hand wipes (data not shown). Hand washing was assessed in the questionnaire during which parents were asked to report the average number of times that their child washed their hands each day (never, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–9, 10+). Because hand washing frequency was not related to OPE concentrations on hand wipes, it was not included in the multivariate analysis. Exponentiated beta coefficients from the models represent multiplicative change in log10-transformed urinary OPE metabolite concentrations relative to the reference category. Statistical significance was set to α = 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Study Population

In total, 203 children from 190 individual homes were recruited for this study, including 1 pair of siblings, 8 sets of twins, and 2 sets of triplets. Approximately 55% of the participants were male and 45% were female, with an overall median age of 54 months or 4.5 years old (Table S1). A more detailed description of the study population can be found in Hoffman et al. (2018). In brief, about 40% of the children were non-Hispanic white, 40% were non-Hispanic black, and the remaining 20% were Hispanic. Maternal educational attainment at birth was split rather equally within the study population, with 56% of mothers having less attainment than a four-year college degree and 44% having earned at least a bachelor’s degree.

OPEs in Individual Matrices

Hand wipes

OPEs were frequently detected on the 202 hand wipe samples taken from the child participants, with TDCIPP measured in every hand wipe (Table 1). Although it was only detected in 59% of the samples, TBOEP was measured at the highest levels of all the OPEs on the hand wipes (GM=606.8 ng/wipe), which is likely due to its prevalence in plastics and perhaps in floor polishes. The detection frequency of TBOEP was similar to a study with adults in Norway but the geometric mean in this study was an order of magnitude greater, suggesting differential exposure between adults and children, or possibly a regional difference between Europe and North America, and possibly China as well, where it was only detected in 8% of samples (Liu et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2016). The chlorinated alkyl phosphates (TCEP, TCIPP, TDCIPP) were all detected in >85% of the hand wipe samples with TDCIPP being the most abundant within this subclass of compounds, similar to a previous study investigating OPEs on children’s hand wipes in the U.S. (Stapleton et al., 2014). On the whole, levels of the chlorinated organophosphate compounds in this study were higher than hand wipes taken from similarly-aged children also from central North Carolina and were significantly higher than wipes taken from toddlers aged 9–18 months in Europe (Stapleton et al., 2014; Sugeng et al., 2017). With the exception of the tert-butylated triaryl phosphates, the aryl phosphate compounds (EHDPHP, TPHP, 2IPPDPP, 4IPPDPP) were detected almost ubiquitously. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time that the ITP and TBPP isomers have been quantitatively analyzed in hand wipes. Across the board, the observed high detection frequency of the chlorinated compounds and several of the aryl phosphates suggests children’s exposure to these compounds is widespread and possibly increasing.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for OPEs and their urinary metabolites.

| Matrix and Compound | Detection Frequency (%) |

MDLab | 10th Percentile |

Geometric Mean |

90th Percentile |

Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand Wipe (ng/wipe) n=202 | ||||||

| TCEP | 87.0 | 2.7 | <MDL | 27.5 | 214.2 | 3,216 |

| TCIPP | 88.0 | 19.8 | <MDL | 89.8 | 466.8 | 2,488 |

| TDCIPP | 100 | 3.9 | 32.0 | 143.6 | 831.6 | 11,911 |

| TBOEP | 59.0 | 497 | <MDL | 740.8 | 3,310 | 8,361 |

| EHDPHP | 95.0 | 0.31 | 3.1 | 14.9 | 66.0 | 361.5 |

| TPHP | 98.0 | 1.1 | 4.0 | 18.2 | 93.8 | 2,468 |

| 2IPPDPP | 99.5 | 0.19 | 1.3 | 7.0 | 36.4 | 2,787 |

| 4IPPDPP | 96.0 | 0.22 | 1.1 | 7.9 | 99.5 | 1,373 |

| 4tBPDPP | 73.0 | 0.09 | <MDL | 0.53 | 3.8 | 364.5 |

| B4tBPPP | 69.0 | 0.37 | <MDL | 2.2 | 27.6 | 965.3 |

| T4tBPP | 42.0 | 0.80 | NAd | NAd | NAd | 398.6 |

| Dust (ng/g) n=188 | ||||||

| TCEP | 98.4 | 18.7 | 216.8 | 864.1 | 3,511 | 167,532 |

| TCIPP | 100 | 45.6 | 1,150 | 4,818 | 28,062 | 468,780 |

| TDCIPP | 100 | 12.1 | 797.9 | 4,843 | 26,799 | 257,917 |

| TBOEP | 97.9 | 51.5 | 995.6 | 6,862 | 69,520 | 2,209,172 |

| EHDPHP | 98.4 | 1.3 | 51.7 | 203.7 | 859.5 | 3,342 |

| TPHP | 100 | 12.4 | 726.0 | 2,582 | 12,202 | 290,982 |

| 2IPPDPP | 80.9 | 10.1 | <MDL | 101.0 | 460.7 | 2,646 |

| 4IPPDPP | 53.2 | 9.2 | <MDL | 29.8 | 190.6 | 1,267 |

| 24DIPPDPPc | 68.6 | 1.7 | <MDL | 58.4 | 921.9 | 6,775 |

| B2IPPPPc | 20.7 | 2.7 | NAd | NAd | NAd | 2,143 |

| B4IPPPPc | 48.4 | 2.6 | NAd | NAd | NAd | 1,183 |

| B24DIPPPPc | 8.0 | 3.5 | NAd | NAd | NAd | 29,637 |

| 4tBPDPP | 94.7 | 2.4 | 65.9 | 510.9 | 2,544 | 85,986 |

| B4tBPPP | 83.5 | 1.9 | <MDL | 70.2 | 438.5 | 12,777 |

| T4tBPP | 29.3 | 2.8 | NAd | NAd | NAd | 525.5 |

| SG-corrected urine (ng/mL) n=181 | ||||||

| BCIPP | 80.1 | 0.14 | <MDL | 0.43 | 1.51 | 31.9 |

| BCIPHIPP | 97.2 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 1.29 | 4.94 | 19.2 |

| BDCIPP | 100 | 0.07 | 1.42 | 5.63 | 23.9 | 80.7 |

| DPHP | 99.4 | 0.12 | 0.92 | 2.67 | 9.53 | 50.9 |

| ip-PPP | 100 | 0.02 | 2.25 | 6.85 | 17.6 | 61.5 |

| tb-PPP | 94.5 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 1.14 | 11.8 |

Dust MDL values were normalized to average mass of dust extracted (0.059 mg).

Urine MDL values were normalized to volume of urine extracted (5 mL).

Compounds were not integrated on hand wipes due to interferences in chromatography

Descriptive statistics were not reported for compounds detected in less than 50% of samples

House dust

The majority of the OPEs were highly detected in house dust samples with TCEP, TCIPP, TDCIPP, TBOEP, EHDPHP and TPHP having detection frequencies >97% (Table 1). Of the OPE compounds analyzed, TBOEP levels were the most abundant in the dust and were similar to levels of TCIPP, which is a trend that has been observed frequently in house dust around the world (Araki et al., 2014; Cequier et al., 2014; Kademoglou et al., 2017). Overall, the OPE levels in dust appear to be similar to or higher than previous studies conducted in the United States, particularly in North Carolina (Hammel et al., 2017; Hoffman et al., 2015; Stapleton et al., 2014; Vykoukalová et al., 2017). The levels of the ITP and TBPP compounds and EHDPHP in dust were generally at least an order of magnitude lower than the other OPEs measured, which suggests either differential use patterns or lower application levels within products.

Urinary Metabolites

OPE metabolites were detected in over 80% of all urine samples, indicating widespread exposure to OPEs for the children in the TESIE study. Both BDCIPP and ip-PPP, metabolites of TDCIPP and the ITP compounds respectively, were detected in every sample, with ip-PPP having the highest geometric mean concentration of 6.9 ng/mL (Figure 1, Table 1). Observed high detection frequencies of OPE metabolites emphasizes the need to determine how children are exposed to these compounds. Discussion of the urinary metabolites and their association with demographic variables is presented in greater detail in Hoffman et al., 2018 (See Supporting Material).

Comparing Hand Wipes and Dust to Urine

The masses of OPEs measured in hand wipe samples were significantly correlated with their corresponding urinary metabolites (rs=0.16–0.41, p<0.05; Table 2). This suggests that hand wipes serve as an effective exposure metric for OPEs, which has previously been shown in studies with both adults and children (Hammel et al., 2016; Hoffman et al., 2015; Stapleton et al., 2014). Particularly noteworthy is that this is the first time that OPEs on hand wipes have been shown to be significantly and positively correlated with urinary metabolites for a wide range of compounds, including EHDPHP, ITPs, and TBPPs. These relationships continue to be significant in the highest quartile of OPE mass on hand wipes when adjusted for child’s age and sex, mother’s race and education, and average outdoor air temperature (Table S4). Recently, the dermal absorption pathway has been shown to be important for many of these OPE compounds (Abou-Elwafa Abdallah et al., 2016). Since hand wipes capture both hand-to-mouth contact and potential dermal absorption, this study provides further evidence that these pathways of exposure are important for OPEs, and particularly for children’s exposures.

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients for OPE and OPE metabolite levels measured in paired hand wipes (n = 180) and dust (n = 179) with ≥60% detection and specific gravity-corrected urine. Shading indicates known parent-metabolite pairs.

| Urine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCIPP | BCIPHIPP | BDCIPP | DPHP | ip-PPP | tb-PPP | ||

| Hand Wipe | TCEP | 0.00 | 0.27† | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.25† | 0.13 |

| TCIPP | 0.27† | 0.16* | 0.27† | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.01 | |

| TDCIPP | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.41† | 0.18# | 0.22# | 0.14 | |

| EHDPHP | 0.09 | 0.22# | 0.07 | 0.19# | 0.11 | 0.08 | |

| TPHP | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.23# | 0.07 | 0.23# | |

| 2IPPDPP | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.32† | 0.23# | 0.31† | |

| 4IPPDPP | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.29† | 0.19# | 0.25† | |

| 4tBPDPP | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.19# | 0.07 | 0.33† | |

| B4TBPPP | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.18# | 0.11 | 0.38† | |

| Dust | TCEP | 0.00 | −0.13 | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.16* |

| TCIPP | 0.13 | −0.14 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.07 | |

| TDCIPP | −0.03 | −0.09 | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.06 | |

| TBOEP | −0.06 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | |

| EHDPHP | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.02 | −0.02 | |

| TPHP | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.13 | −0.08 | |

| 2IPPDPP | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.08 | −0.12 | −0.10 | |

| 24DIPPDPP | 0.02 | 0.16* | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| 4tBPDPP | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.18* | |

| B4TBPPP | −0.09 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.27† | |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

The correlation between TDCIPP on hand wipes and urinary BDCIPP was the strongest of any paired samples (rs=0.41, p<0.001) and stronger than the correlation with TDCIPP in dust. After adjusting for other covariates, a significant relationship between TDCIPP and urinary BDCIPP was observed for every quartile of hand wipe mass with a clear increasing trend (p for trend=0.001; Figure 2). This suggested that of the OPEs assessed in this study, TDCIPP exposure was best classified by the hand wipes, with the sensitivity to differentiate exposure within each quartile of TDCIPP mass on hand wipes.

Figure 2.

Because TCIPP has two potential metabolites, associations between TCIPP and each of its metabolites, BCIPP and BCIPHIPP, were examined (Figure 1). TCIPP levels on hand wipes were significantly correlated with both urinary metabolites, although the magnitude of correlation was greater for BCIPP compared to BCIPHIPP. Although BCIPHIPP is a urinary metabolite of TCIPP, recent studies suggest that children may have immature or decreased expression of enzymes responsible for converting TCIPP to BCIPHIPP compared to adults (Van den Eede et al., 2015, 2013). When the relationship between TCIPP levels on hand wipes and its two urinary metabolites was evaluated while adjusting for child’s sex and age, race, mother’s education, and average outdoor temperature, the association between TCIPP and BCIPHIPP was no longer significant while the TCIPP-BCIPP association followed a dose response relationship and was significant in the highest hand wipe quartile (Table S4). This may suggest that BCIPP is a better urinary biomarker of exposure for children compared to adults; however, further studies are warranted to examine the different metabolic activities of TCIPP in children versus adults.

Among the aryl phosphates, TPHP, EHDPHP, and the four ITP and TBPP compounds were all significantly correlated with DPHP (rs=0.18–0.32, p<0.01). This result was not unsurprising since all of these compounds can be metabolized to DPHP. After adjusting for covariates in a regression analysis, the relationship between hand wipes and DPHP remained significant for EHPDP, TPHP, and the two ITP compounds, although generally only for the highest quartile of exposure measured by hand wipes (Table S4). Additionally, the two ITP compounds measured in the hand wipes, 2IPPDPP and 4IPPDPP, were significantly correlated with ip-PPP (rs=0.23, 0.19, p<0.01). This further contributed evidence for ip-PPP as a biomarker of exposure for the ITP compounds, which was previously shown in an in vivo animal model (Phillips et al., 2016). The two TBPP compounds on the hand wipes, 4tBPDPP and B4TBPPP, were strongly correlated with tb-PPP in urine (rs=0.33, 0.38, p<0.001). To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of frequent detection of tb-PPP in urine. Tb-PPP has been previously suggested to be a metabolite of the TBPP compounds, and the significant correlation here provides evidence in support of this claim (Butt et al., 2014). Along with TPHP, the two ITP compounds on hand wipes were also significantly correlated with tb-PPP (rs=0.23–0.31, p<0.01). Because TPHP is a component of the TBPP mixture this association likely reflect co-exposure of the parent compounds even though TPHP is unlikely to be metabolized to tb-PPP, (Phillips et al., 2017; Van den Eede et al., 2013). The significant correlation of 2IPPDPP and 4IPPDPP with tb-PPP may also be explained by the detection of trace amounts of ITP compounds in the Firemaster® 600 and TBPP mixtures, thereby also reflecting co-exposure of the parent compounds (Phillips et al., 2017).

In general, OPE urinary metabolites were not associated with the parent compounds in dust with the exception of the TBPP compounds and tb-PPP metabolite (rs=0.18–0.27, p<0.05; Table 2, Table S5). This suggested that inadvertent dust ingestion may not be the primary route of exposure for the majority of the OPEs. For compounds with relatively higher molecular weights and lower vapor pressures, such as PBDEs and the TBPP compounds, this pathway of exposure may be of greater importance (Stapleton et al., 2012). House dust could also be a source of TBPP compounds on the hand wipes, since both dust and hand wipes were positively associated with urinary tb-PPP. Overall, due to the greater magnitude of the correlation coefficients and results from the regression analyses, hand wipes appear to be a better measure of exposure compared to dust for OPEs. This may be a result of hand wipes capturing exposure to OPEs via hand-to-mouth contacts in addition to various behavioral attributes of the children. Hand wipes also are more likely to integrate exposures from multiple microenvironments whereas dust likely represents exposure solely from one microenvironment, which in this case was the main living area of the home (Watkins et al., 2012).

Comparing OPEs in Dust and Hand Wipes

Several of the OPEs (TCIPP, TBOEP, TPHP, 2IPPDPP, 4tBPDPP, and B4TBPPP) showed positive and significant correlations between paired hand wipes and dust (rs=0.16–0.30, p<0.05; Table 3). The ITPs in dust were associated with the ITP compounds on hand wipes (rs=0.15–23, p<0.05), suggesting similar sources of exposure due to mixtures applications as well as the potential for indoor dust to be a source of ITPs on children’s hands. Additionally, 24DIPPDPP in dust was significantly correlated with both the ITP and TBPP compounds and TPHP on hand wipes, which further points to the potential of co-application of some of these compounds in mixtures. TBOEP on hand wipes and in dust was significantly and positively correlated (rs=0.23, p<0.05), which has not been previously observed to the authors’ knowledge. The high abundance of TBOEP in both hand wipes and dust suggests that house dust may serve as a primary exposure pathway to children’s hands. Surprisingly, no association was observed between hand wipes and dust for TCEP, TDCIPP, and EHDPHP. Inhalation and dermal exposure, and not dust ingestion, have previously been postulated to be the strongest exposure pathway for TDCIPP (Babich, 2006; Schreder et al., 2016). While dust may still serve as an important measure for assessing exposure to OPEs in the home, hand wipes may be a more holistic exposure metric for OPEs. This was also observed among adults, where hand wipes were a stronger predictor of urinary OPE metabolites than house dust (Hoffman et al., 2015). For children, hand wipes may be an even better predictor of exposure due to their ability to capture behavioral differences, and in particular, increased hand-to-mouth contact compared to adults.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation coefficients for OPE levels measured in paired hand wipes and dust (n = 200) with ≥60% detection.

| Dust | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCEP | TCIPP | TDCIPP | EHDPHP | TBOEP | TPHP | 2IPPDPP | 24DIPPDPP | 4tBPDPP | B4TBPPP | ||

| Hand Wipe | TCEP | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.09 | −0.19# | −0.15* |

| TCIPP | 0.07 | 0.20# | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.09 | −0.15* | −0.09 | |

| TDCIPP | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.00 | |

| EHDPHP | −0.10 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.09 | −0.08 | |

| TBOEP | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.23# | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.11 | −0.01 | |

| TPHP | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.17# | 0.14 | 0.15* | 0.01 | 0.06 | |

| 2IPPDPP | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.16* | 0.23† | −0.01 | 0.05 | |

| 4IPPDPP | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.13 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.15* | 0.19# | −0.06 | −0.01 | |

| 4tBPDPP | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.13 | 0.23† | 0.22# | 0.27† | |

| B4TBPPP | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.20# | 0.23† | 0.30† | |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Effect of Covariates

When using generalized estimating equations to examine associations between urine, hand wipes, and dust, all models were adjusted for the child’s age and sex, mother’s education and race, and average outdoor temperature. Of these covariates, levels of the OPE compound on hand wipes was generally the most consistently associated variable with the corresponding urinary metabolite (Table 4). Mother’s race and education contributed to the models but were not significant except for the relationship between 4tBDPP on hand wipes and tb-PPP in urine, with children whose mothers attained a four-year college degree and were Hispanic having about half as high levels of tb-PPP (p<0.05) compared to the reference group. Average outdoor air temperature was a significant predictor of BDCIPP (10β=1.04, p<0.0001), which corresponds to seasonal trends in urinary metabolite concentrations that have been previously described in Hoffman et al. (2017). Our finding suggests that urinary concentrations of BDCIPP will increase by 4% per each 1°C increase in outdoor temperature. Seasonal trends for OPEs in indoor dust have also been observed, with higher levels in warmer months, and have been attributed to the greater volatility of these compounds compared to brominated flame retardants (Cao et al., 2014). Because TDCIPP is used in automobile upholstery, it is possible that this trend stems from increased off-gassing inside automobiles with elevated outdoor temperature (Christia et al., 2018). Only one family reported not having central air/heating so we would not expect to see significant seasonal differences in indoor temperature and ventilation in this study. While an impact with every parent-metabolite pair was not observed, the seasonal trends observed suggested an increase in OPE concentrations and exposure during warmer months. This indicates that season and outdoor temperature needs to be taken into account during exposure assessments for OPE compounds, as biases in exposure estimates may result within a specific sampling time period.

Table 4.

Results of regression analyses for predicting urinary metabolites based on parent compounds on hand wipes, adjusted for sex, mother’s race/ethnicity, mother’s education, age, and average outdoor temperature.

| Predictor | Parent on Hand wipe – Urinary Metabolite

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCIP P - BCIP P [10β (95% CI)-p Value ] |

TDCI PP - BDC IPP [10β (95% CI)- p- Value ] |

2IPP DPP – DPH P [10β (95% CI)- p- Value ] |

4tBP DPP –tb- PPP [10β (95% CI)- p- Value ] |

||

| Age | ≤54 months (referent) | ||||

| >54 months | 0.86 (0.57,1.30)−0.47 | 1.21 (0.86,1.70)−0.26 | 0.80 (0.57,1.11)−0.18 | 1.34 (0.90,1.99)−0.15 | |

|

| |||||

| Child Sex | Female (referent) | ||||

| Male | 1.04 (0.74,1.47)−0.81 | 0.91 (0.68,1.23)−0.54 | 0.87 (0.66,1.15)−0.33 | 1.12 (0.78,1.60)−0.55 | |

|

| |||||

| Mother’s Education | No college degree (referent) | ||||

| College degree | 1.57 (0.99,2.49)−0.05 | 1.32 (0.91,1.91)−0.15 | 0.78 (0.50,1.22)−0.28 | 0.50 (0.33,0.75)−0.00 | |

| 4 | 1 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Mother’s Racea | Non-Hispanic white (referent) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.24 (0.78,1.98)−0.37 | 0.98 (0.61,1.57)−0.93 | 0.91 (0.57,1.46)−0.70 | 0.77 (0.49,1.22)−0.27 | |

| Hispanic | 1.09 (0.61,1.94)−0.76 | 0.77 (0.44,1.34)−0.36 | 0.51 (0.46,1.38)−0.41 | 0.57 (0.34,0.95)−0.031 | |

|

| |||||

| Average Outdoor Temperature | (°C) | 1.01 (0.99,1.04)−0.40 | 1.04 (1.03,1.07)−<0.0001 | 1.01 (0.99,1.03)−0.17 | 1.01 (0.99,1.04)−0.27 |

|

| |||||

| Hand Wipe | Quartile 1 (referent) | ||||

| Quartile 2 | 1.09 (0.69,1.72)−0.71 | 1.52 (1.04,2.23)−0.032 | 1.11 (0.76,1.60)−0.59 | 1.51 (1.04,2.19)−0.032 | |

| Quartile 3 | 1.19 (0.79,1.80)−0.41 | 2.56 (1.72,3.82)−<0.0001 | 1.12 (0.75,1.67)−0.57 | 1.19 (0.74,1.90)−0.48 | |

| Quartile 4 | 1.84 (1.19,2.84)−0.006 | 2.73 (1.67,4.48)−<0.0001 | 2.11 (1.31,3.40)−0.002 | 2.65 (1.56,4.49)−0.0003 | |

| p-Value for trend | 0.30 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.004 | |

Three participants reporting mother’s race/ethnicity as “other” were excluded from adjusted models.

Exposure Pathways

Our results suggest that hand wipes serve as an improved metric of exposure for OPEs compared to house dust. While levels in dust and hand wipes may be significantly correlated, hand wipes serve as a stronger predictor of urinary metabolite concentrations (Tables 2, S4, S5). The correlations between dust and hand wipes suggest that house dust could be a source of OPEs found on children’s hands, but this was mostly observed for the higher molecular weight ITP and TBPP compounds. Despite having similar structures, different applications of OPEs in consumer products (e.g. flame retardant or plasticizer), differing levels of OPEs in products, and varying physicochemical properties likely dictate the differences observed in potential exposure pathways. Hand wipes have been postulated to capture exposure via hand-to-mouth contact as well as dermal absorption via sampling of skin-surface lipids. This could be explained by SVOCs partitioning from the air to skin-surface lipids, followed by absorption into the body (Weschler and Nazaroff, 2012, 2008). OPE levels on skin may also reflect contact with dust or surfaces and direct contact with products. Exposure to OPEs contrasts with the brominated flame retardants, and in particular the PBDEs, for which household dust levels have been significantly and positively associated with serum biomarkers implicating dust ingestion as a primary route of exposure (Johnson et al., 2010; Stapleton et al., 2012, 2008; Zota et al., 2008). Alternatively, differential OPE and PBDE exposure may partly reflect usage patterns in the home and/or other microenvironments. As such, additional work to further characterize pathways of exposure for the OPEs is needed.

Limitations and Strengths

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of a few potential limitations. First, the study population was a convenience sample that was selected from a pregnancy cohort. This limits the generalizability of the results to the general population of children within the U.S. but should not impact the internal validity of the study. In addition, the study design provided a cross-sectional analysis of the indoor home environment, which limits our ability to examine long-term exposures to OPEs, and many of these compounds are rapidly metabolized. Here, we used a composite sample comprised of three urine samples per child to examine exposure to OPEs over a 48-hour period. We intended to capture exposure from young children and our study population contains children between ages 3–6 years; however, children who are under the age of 3 may have more hand-to-mouth contact and thus hand wipes may be an even stronger measure of exposure for these individuals. We only sampled dust from one microenvironment, the main living area; this may not correctly measure exposure to dust in other areas of the home or outside the home (e.g., school). Similarly, handwipes were collected at a single point in time; although our past work in adults demonstrated that handwipe OPE concentrations are significantly correlated with pooled urine samples (across 5 days) and suggests that a single handwipe provides information on average exposure over time (Hammel et al., 2017), levels of OPEs on children’s hands likely vary throughout the day and over time. In addition, we did not analyze for OPE metabolites such as DPHP in the house dust or hand wipes, although they have been recently detected in indoor dust samples (Björnsdotter et al., 2018). We did not assess potential exposure via diet or inhalation; inhalation exposure will be assessed in a future study via passive air samplers that were deployed in a subset of these homes. A model that includes the contribution of these other exposure pathways, various microenvironments, and individual behavior would likely better predict exposure. As we performed multiple statistical tests, some statistically significant results may be due to chance.

Despite these weaknesses, our study has several strengths including the collection of multiple samples (urine, hand wipes, house dust) and the use of a pooled urine sample per child (rather than a single spot urine). It is the first study to report children’s exposure to a large suite of novel, aryl OPEs in various matrices. Additionally, this study population is unprecedented in the OPE literature, both in terms of sample size (n=203) and participant age (~3–6 years). Other somewhat similar studies differ from the current study: Hoffman et al. (2015) assessed OPEs on hand wipes and dust in 53 adults. Children’s behavior is markedly different from adult behavior and has been known to affect SVOC exposure. Stapleton et al. (2014) also assessed OPEs on hand wipes in 43 children, but comparison to urinary biomarkers was not included. Our study is the first to assess OPE exposure in a large children’s cohort, documenting associations between parent levels on hand wipes and in dust with metabolite levels in urine.

Conclusion

While numerous in vitro toxicology studies have reported adverse health effects of OPE exposures, in vivo studies are needed to investigate potential health effects at the levels of OPE exposure described herein. In particular, developmental toxicity should be considered as children are potentially more vulnerable to OPEs. Taken together, our study indicates that OPE exposures are nearly ubiquitous for TESIE participants, and possibly also for other young children in the U.S. Dermal absorption and hand-to-mouth contact are likely important contributors to cumulative OPE exposure, as OPE levels on hand wipes were associated with urinary metabolite concentrations. This is the first study to show that hand wipes are more useful than indoor dust for estimating children’s exposure to OPEs, which should be taken into account in future epidemiological studies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Exposure to organophosphate flame retardants and plasticizers was measured in children.

OPEs were measured in paired samples of handwipes, house dust and urine.

Handwipe levels of OPEs were more strongly associated with urine than house dust.

Average outdoor air temperature was a significant predictor of urinary BDCIPP.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Grant 83564201) and NIEHS (R01 ES016099). Additional support for ALP was provided by NIEHS (T32-ES021432). We also thank our participants for opening their homes to our study team and helping us gain a better understanding of children’s exposures to SVOCs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Associated Content

Additional information is available on the study population demographics (Table S1), blank levels of analytes in each matrix (Table S2), within matrix correlations (Table S3), and regression analyses for the relationships between hand wipes and urine (Table S4) and dust and urine (Table S5).

Author Information

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abou-Elwafa Abdallah M, Pawar G, Harrad S. Human dermal absorption of chlorinated organophosphate flame retardants; implications for human exposure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016;291:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antweiler RC, Taylor HE. Evaluation of Statistical Treatments of Left-Censored Environmental Data using Coincident Uncensored Data Sets: I. Summary Statistics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:3732–3738. doi: 10.1021/es071301c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki A, Saito I, Kanazawa A, Morimoto K, Nakayama K, Shibata E, Tanaka M, Takigawa T, Yoshimura T, Chikara H, Saijo Y, Kishi R. Phosphorus flame retardants in indoor dust and their relation to asthma and allergies of inhabitants. Indoor Air. 2014;24:3–15. doi: 10.1111/ina.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babich MA. CPSC Staff Preliminary Risk Assessment of Flame Retardant FR Chemicals in Upholstered Furniture Foam. Bethesda, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Behl M, Rice JR, Smith MV, Co CA, Bridge MF, Hsieh J-H, Freedman JH, Boyd WA. Editor’s Highlight: Comparative Toxicity of Organophosphate Flame Retardants and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers to Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicol. Sci. 2016;154:241–252. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergh C, Torgrip R, Emenius G, Östman C. Organophosphate and phthalate esters in air and settled dust - a multi-location indoor study. Indoor Air. 2011;21:67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2010.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björnsdotter MK, Romera-García E, Borrull J, de Boer J, Rubio S, Ballesteros-Gómez A. Presence of diphenyl phosphate and aryl-phosphate flame retardants in indoor dust from different microenvironments in Spain and the Netherlands and estimation of human exposure. Environ. Int. 2018;112:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeniger MF, Lowry LK, Rosenberg J. Interpretation of Urine Results used to Assess Chemical Exposure with Emphasis on Creatinine Adjustments: A Review. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 1993;54:615–627. doi: 10.1080/15298669391355134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell L, Harrad S, Abou-Elwafa Abdallah M, Rauert C, Rose M, Fernandes A, Pless-Mulloli T. Predictors of human PBDE body burdens for a UK cohort. Chemosphere. 2017;189:186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt CM, Congleton J, Hoffman K, Fang M, Stapleton HM. Metabolites of organophosphate flame retardants and 2-ethylhexyl tetrabromobenzoate in urine from paired mothers and toddlers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:10432–8. doi: 10.1021/es5025299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt CM, Hoffman K, Chen A, Lorenzo A, Congleton J, Stapleton HM. Regional comparison of organophosphate flame retardant (PFR) urinary metabolites and tetrabromobenzoic acid (TBBA) in mother-toddler pairs from California and New Jersey. Environ. Int. 2016;94:627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Xu F, Covaci A, Wu M, Yu G, Wang B, Deng S, Huang J. Differences in the seasonal variation of brominated and phosphorus flame retardants in office dust. Environ. Int. 2014;65:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cequier E, Ionas AC, Covaci A, Marcé RM, Becher G, Thomsen C. Occurrence of a Broad Range of Legacy and Emerging Flame Retardants in Indoor Environments in Norway. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:6827–6835. doi: 10.1021/es500516u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christia C, Poma G, Besis A, Samara C, Covaci A. Legacy and emerging organophosphοrus flame retardants in car dust from Greece: Implications for human exposure. Chemosphere. 2018;196:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.12.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper EM, Covaci A, van Nuijs ALN, Webster TF, Stapleton HM. Analysis of the flame retardant metabolites bis(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (BDCPP) and diphenyl phosphate (DPP) in urine using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011;401:2123–32. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5294-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper EM, Kroeger G, Davis K, Clark CR, Ferguson PL, Stapleton HM. Results from Screening Polyurethane Foam Based Consumer Products for Flame Retardant Chemicals: Assessing Impacts on the Change in the Furniture Flammability Standards. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:10653–10660. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b01602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covaci A. Personal Communication 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen M, Stapleton HM, Vorkamp K, Webster TF, Jensen NM, Sørensen JA, Nielsen F, Knudsen LE, Sørensen LS, Clausen PA, Nielsen JB. Dermal uptake and percutaneous penetration of organophosphate esters in a human skin ex vivo model. Chemosphere. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. Flame Retardant Chemicals: Technologies and Global Markets. Wellesley; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hammel SC, Hoffman K, Lorenzo AM, Chen A, Phillips AL, Butt CM, Sosa JA, Webster TF, Stapleton HM. Associations between flame retardant applications in furniture foam, house dust levels, and residents’ serum levels. Environ. Int. 2017;107:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel SC, Hoffman K, Webster TF, Anderson KA, Stapleton HM. Measuring Personal Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants Using Silicone Wristbands and Hand Wipes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:4483–4491. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Butt CM, Webster TF, Preston EV, Hammel SC, Makey C, Lorenzo AM, Cooper EM, Carignan C, Meeker JD, Hauser R, Soubry A, Murphy SK, Price TM, Hoyo C, Mendelsohn E, Congleton J, Daniels JL, Stapleton HM. Temporal Trends in Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017a doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Garantziotis S, Birnbaum LS, Stapleton HM. Monitoring indoor exposure to organophosphate flame retardants: hand wipes and house dust. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015;123:160–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Gearhart-Serna L, Lorber M, Webster TF, Stapleton HM. Estimated Tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) Phosphate Exposure Levels for U.S. Infants Suggest Potential Health Risks. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017b;4:334–338. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.7b00196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Hammel SC, Phillips AL, Lorenzo AM, Chen A, Calafat AM, Ye X, Webster TF, Stapleton HM. Children’s Exposure to SVOC Mixtures: The TESIE Study. Environ. Int. In preparation. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyo C, Murtha AP, Schildkraut JM, Forman MR, Calingaert B, Demark-Wahnefried W, Kurtzberg J, Jirtle RL, Murphy SK. Folic acid supplementation before and during pregnancy in the Newborn Epigenetics STudy (NEST) BMC Public Health. 2011;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PI, Stapleton HM, Sjodin A, Meeker JD. Relationships between Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether Concentrations in House Dust and Serum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:5627–5632. doi: 10.1021/es100697q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Otazo HA, Clarke JP, Diamond ML, Archbold JA, Ferguson G, Harner T, Richardson GM, Ryan JJ, Wilford B. Is House Dust the Missing Exposure Pathway for PBDEs? An Analysis of the Urban Fate and Human Exposure to PBDEs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:5121–5130. doi: 10.1021/es048267b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kademoglou K, Xu F, Padilla-Sanchez JA, Haug LS, Covaci A, Collins CD. Legacy and alternative flame retardants in Norwegian and UK indoor environment: Implications of human exposure via dust ingestion. Environ. Int. 2017;102:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye EF. Statement of Commissioner Elliot F. Kaye on the Petition on Organohalogen Flame Retardants. Bethesda, MD: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Yu G, Cao Z, Wang B, Huang J, Deng S, Wang Y. Occurrence of organophosphorus flame retardants on skin wipes: Insight into human exposure from dermal absorption. Environ. Int. 2017;98:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber M. Exposure of Americans to polybrominated diphenyl ethers. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2008;18:2–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.jes.7500572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes PD, Haggard DE, Gonnerman GD, Tanguay RL. Advanced Morphological — Behavioral Test Platform Reveals Neurodevelopmental Defects in Embryonic Zebrafish Exposed to Comprehensive Suite of Halogenated and Organophosphate Flame Retardants. Toxicol. Sci. 2015;145:177–195. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KM, Upson K, Cook NR, Weinberg CR. Environmental Chemicals in Urine and Blood: Improving Methods for Creatinine and Lipid Adjustment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015:124. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ospina M, Jayatilaka NK, Wong L-Y, Restrepo P, Calafat AM. Exposure to organophosphate flame retardant chemicals in the U.S. general population: Data from the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environ. Int. 2018;110:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AL, Chen A, Rock KD, Horman B, Patisaul HB, Stapleton HM. Transplacental and Lactational Transfer of Firemaster® 550 Components in Dosed Wistar Rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2016;153:246–257. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AL, Hammel SC, Konstantinov A, Stapleton HM. Characterization of Individual Isopropylated and tert -Butylated Triarylphosphate (ITP and TBPP) Isomers in Several Commercial Flame Retardant Mixtures and House Dust Standard Reference Material SRM 2585. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:13443–13449. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b04179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston EV, McClean MD, Claus Henn B, Stapleton HM, Braverman LE, Pearce EN, Makey CM, Webster TF. Associations between urinary diphenyl phosphate and thyroid function. Environ. Int. 2017;101:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosens L, Abdallah MA-E, Harrad S, Neels H, Covaci A. Factors Influencing Concentrations of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Students from Antwerp, Belgium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:3535–3541. doi: 10.1021/es900571h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlström LMO, Sellström U, De Wit CA, Lignell S, Darnerud PO. Brominated flame retardants in matched serum samples from Swedish first-time mothers and their toddlers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:7584–7592. doi: 10.1021/es501139d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schang G, Robaire B, Hales BF. Organophosphate Flame Retardants Act as Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in MA-10 Mouse Tumor Leydig Cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2016;150:499–509. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreder ED, Uding N, La Guardia MJ. Inhalation a significant exposure route for chlorinated organophosphate flame retardants. Chemosphere. 2016;150:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Skavicus S, Stapleton HM, Seidler FJ. Brominated and organophosphate flame retardants target different neurodevelopmental stages, characterized with embryonic neural stem cells and neuronotypic PC12 cells. Toxicology. 2017;390:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Eagle S, Sjödin A, Webster TF. Serum PBDEs in a North Carolina toddler cohort: Associations with handwipes, house dust, and socioeconomic variables. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120:1049–1054. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Kelly SM, Allen JG, Mcclean MD, Webster TF. Measurement of polybrominated diphenyl ethers on hand wipes: Estimating exposure from hand-to-mouth contact. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:3329–3334. doi: 10.1021/es7029625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Klosterhaus S, Eagle S, Fuh J, Meeker JD, Blum A, Webster TF. Detection of organophosphate flame retardants in furniture foam and U.S. house dust. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:7490–7495. doi: 10.1021/es9014019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Misenheimer J, Hoffman K, Webster TF. Flame retardant associations between children’s handwipes and house dust. Chemosphere. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.12.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugeng EJ, Leonards PEG, van de Bor M. Brominated and organophosphorus flame retardants in body wipes and house dust, and an estimation of house dust hand-loadings in Dutch toddlers. Environ. Res. 2017;158:789–797. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eede N, Dirtu AC, Ali N, Neels H, Covaci A. Multi-residue method for the determination of brominated and organophosphate flame retardants in indoor dust. Talanta. 2012;89:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eede N, Dirtu AC, Neels H, Covaci A. Analytical developments and preliminary assessment of human exposure to organophosphate flame retardants from indoor dust. Environ. Int. 2011;37:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eede N, Heffernan AL, Aylward LL, Hobson P, Neels H, Mueller JF, Covaci A. Age as a determinant of phosphate flame retardant exposure of the Australian population and identification of novel urinary PFR metabolites. Environ. Int. 2015;74:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eede N, Maho W, Erratico C, Neels H, Covaci A. First insights in the metabolism of phosphate flame retardants and plasticizers using human liver fractions. Toxicol. Lett. 2013;223:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vykoukalová M, Venier M, Vojta Š, Melymuk L, Bečanová J, Romanak K, Prokeš R, Okeme JO, Saini A, Diamond ML, Klánová J. Organophosphate esters flame retardants in the indoor environment. Environ. Int. 2017;106:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, McClean MD, Fraser AJ, Weinberg J, Stapleton HM, Sjödin A, Webster TF. Impact of Dust from Multiple Microenvironments and Diet on PentaBDE Body Burden. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:1192–1200. doi: 10.1021/es203314e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, McClean MD, Fraser AJ, Weinberg J, Stapleton HM, Sjödin A, Webster TF. Exposure to PBDEs in the office environment: Evaluating the relationships between dust, handwipes, and serum. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:1247–1252. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensing M, Uhde E, Salthammer T. Plastics additives in the indoor environment -Flame retardants and plasticizers. Sci. Total Environ. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weschler CJ, Nazaroff WW. SVOC exposure indoors: fresh look at dermal pathways. Indoor Air. 2012;22:356–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2012.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weschler CJ, Nazaroff WW. Semivolatile organic compounds in indoor environments. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:9018–9040. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.09.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Herrmann T, Paepke O, Tickner J, Hale R, Harvey E, La Guardia M, McClean MD, Webster TF. Human Exposure to PBDEs: Associations of PBDE Body Burdens with Food Consumption and House Dust Concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:1584–1589. doi: 10.1021/es0620282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Giovanoulis G, van Waes S, Padilla-Sanchez JA, Papadopoulou E, Magnér J, Haug LS, Neels H, Covaci A. Comprehensive Study of Human External Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants via Air, Dust, and Hand Wipes: The Importance of Sampling and Assessment Strategy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:7752–7760. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zota AR, Rudel RA, Morello-Frosch RA, Brody JG. Elevated house dust and serum concentrations of PBDEs in California: unintended consequences of furniture flammability standards? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:8158–64. doi: 10.1021/es801792z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.