Abstract

Background

Term nulliparous women have the greatest variation across hospitals and providers in cesarean rates and therefore present an opportunity to improve quality through optimal care. We evaluated associations between provider type and mode of birth, including examination of intrapartum management in healthy, laboring nulliparous women.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study using prospectively collected perinatal data from a U.S. academic medical center (2005–2012). Sample included healthy nulliparous women with spontaneous labor onset and term, singleton, vertex fetus managed by either obstetricians or certified nurse-midwives. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression used to compare labor interventions and mode of birth by provider type.

Results

Total of 1339 women received care by an obstetrician (n=749) or nurse-midwife (n=590). Cesarean rate was 13.4% (179/1339). Adjusting for maternal and pregnancy characteristics, care by obstetricians was associated with increased risk of unplanned cesarean birth (aOR 1.48, [95% CI, 1.04–2.12]) compared to care by midwives. Obstetricians more frequently used oxytocin augmentation (aOR 1.41, 95% CI [1.10–1.80]), neuraxial anesthesia (aOR 1.69, 95% CI [1.29–2.23]), and operative vaginal delivery with forceps or vacuum (aOR 2.79, 95% CI [1.75–4.44]). Adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes were not different by provider type across all modes of birth, but were more frequent in women having cesarean compared to vaginal births.

Discussion

In low-risk nulliparous laboring women, care by obstetricians compared to nurse-midwives was associated with increased risk of labor interventions and operative birth. Changes in labor management or increased use of nurse-midwives could decrease the rate of a first cesarean in low-risk laboring women.

Keywords: certified nurse-midwife, cesarean birth, intrapartum care, maternal obesity, nulliparous, obstetrician, oxytocin augmentation, spontaneous labor

INTRODUCTION

Cesarean birth has increased steadily for several decades in the U.S. across all gestational ages, maternal ages, and racial groups.1–3 The women with the highest variation in cesarean rates are nulliparous with term gestation of a singleton fetus in vertex presentation. Cesarean births in low-risk nulliparous women most often occur for rather subjective clinical indications such as labor dystocia or non-reassuring fetal status.4 Intrapartum decision-making therefore contributes strongly to the wide hospital-specific variation in cesarean rates.5

Although cesarean birth is a relatively safe procedure with extremely low maternal mortality, morbidity after primary cesarean and in subsequent pregnancies is concerning due to increased wound complications, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, bladder injury, obstetrical hemorrhage, placenta previa/accreta, and cesarean hysterectomy.6,7 Additionally, there is growing recognition of risks to offspring born by cesarean, such as short-term respiratory compromise requiring neonatal intensive care8 and long term increased reactive airway disease, diabetes, and obesity.9–11 Although cesareans in the U.S. have decreased slightly since 2009,3 in a recent worldwide analysis of cesarean births by large United Nations geographical areas, only the Latin America region had higher overall cesarean rates than North America.12 A first cesarean birth contributes substantially to the overall cesarean rate, as most women subsequently have planned repeat cesarean birth.13 With 10-fold variation in cesarean rates across U.S. hospitals,5 identifying changes in care delivery to prevent a first cesarean is an important quality goal.

Certified nurse midwives (CNMs) have been found to use fewer intrapartum medical interventions compared to obstetricians (OBs) and may achieve higher rates of spontaneous vaginal birth without increased complications,14–18 but CNMs currently attend less than 10% of births in the United States.19 Although many trials comparing labor outcomes by provider type have been conducted in other countries,14 the data on associations between provider type and cesarean risk in the U.S. are more limited in design and scope.15,16,18,20 Given the unique circumstances of the population and health care in the U.S., additional studies are needed to inform obstetric management and health policy. We used a prospectively collected perinatal database of all deliveries in a U.S. academic medical center where CNMs care for nearly half of all laboring women to evaluate the relationship between provider type and other demographic and management factors on the outcome of unplanned cesarean birth. We estimated the risk of unplanned cesarean birth by provider type (OB or CNM) in healthy, spontaneously laboring nulliparous women at term gestation with a singleton, vertex fetus. We hypothesized that OB provider type is associated with more frequent unplanned cesarean birth and with increased use of intrapartum interventions including artificial rupture of membranes, neuraxial anesthesia, synthetic oxytocin administration, and amnioinfusion.

METHODS

Study Population

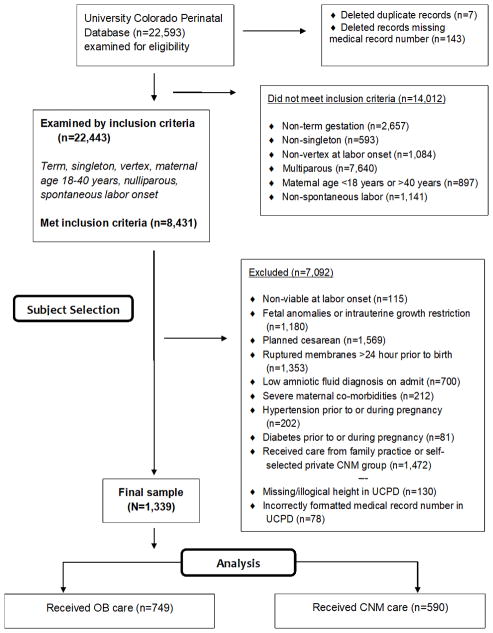

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the University of Colorado Perinatal Database, which contains data abstracted by trained research assistants from the hospital chart and from patient interviews for all births occurring at the University of Colorado Hospital labor and delivery unit between October 1, 2005 and December 31, 2012 (total n=22,593; Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were: nulliparity, singleton fetus in vertex presentation, term gestation (37 0/7 through 41 6/7 weeks based on certain first day of last menstrual period and/or first-trimester ultrasound), maternal age 18 through 40 years, and spontaneous onset of painful contractions with progressive cervical change prior to admission for birth. Women were excluded for the following, in order: intrauterine fetal death, major fetal anomaly (chromosomal or ultrasound evidence), intrauterine fetal growth restriction, planned cesarean birth, prolonged premature rupture of membranes (>24 hours prior to birth), low amniotic fluid (anhydramnios or oligohydramnios), severe maternal co-morbidities (cancer, major cardiac disease), chronic or gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and pregestational or gestational diabetes. We excluded women who self-selected care from a private midwifery group or family practice group, as these practices attracted women with different demographic characteristics and used different practice protocols than regular staff CNMs or OBs. Those women missing medical record numbers or information needed to calculate maternal birth BMI were also excluded. Although BMI ≥ 30kg/m2 is linked to a range of co-morbidities21 and to cesarean birth,22 we retained healthy women with BMIs in this range for our sample with the rationale that in a contemporary population, higher maternal BMI is common.23 We excluded women with major co-morbidities, and examined the distribution of more minor co-morbidities in our provider-defined groups. We conducted a priori sample size calculations, estimating a target of 547 subjects per group (alpha = 0.05, power = 0.80) to distinguish a 10% absolute risk difference between provider types with a baseline cesarean birth rate of 15%.1 The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved the study (#14-0557).

Figure 1. Subject Selection Flowsheet.

Application of inclusion and exclusion criteria for cohort determination. UCPD=University of Colorado Perinatal Database-OB=Obstetrician-CNM=Certified Nurse-Midwife.

Study Variables

To confirm perinatal database accuracy, we compared all values of the study variables with the medical record for 348 randomly-selected subjects (26%) and found >98% agreement. Provider type was confirmed in random chart review and by comparison to a separate CNM birth dataset. We found no errors for provider assignment or mode of birth.

All CNMs and OBs caring for women in this analysis were hospital staff. Providers in other, non-hospital group practices or private practices were excluded. In this health system, most low-risk women calling for a first prenatal visit are scheduled in the next available appointment with either a CNM or OB. Additionally, some low-risk women receive care in community clinics based on proximity to the patient’s home; these clinics are staffed by either OBs or CNMs, and the delivering provider type at our hospital is the same. Although OBs care for all women with complicated pregnancy, we limited our cohort to healthy, low risk women. CNMs and OBs at this hospital use the same institutional protocols and have common nursing staff, and CNM practice is independent unless complications arise for which OB consultation is requested. Both CNM and OB practices include trainees. Although operative vaginal births and cesarean require transfer of care during labor from CNM to OB, we analyzed by original provider type only.

Among other variables in the dataset, maternal race and ethnicity were self-reported. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was calculated using height and weight prior to pregnancy or in the first trimester, then classified by World Health Organization criteria.24 In addition, we calculated maternal BMI at the time of hospital admission for labor (maternal birth BMI).25 Maternal birth BMI incorporates gestational weight gain, thus better reflecting maternal physiology during labor compared to pre-pregnancy BMI.25–27

Gestational age at birth and neonatal birth weight (proxy for estimated fetal weight) were obtained from the birth summary. We obtained data on labor complications of intrapartum fever (>38.0°C) and chorioamnionitis (diagnosed and treated intrapartum with antibiotics per medical record), and on labor interventions including artificial rupture of membranes, neuraxial anesthesia (epidural or combined spinal-epidural), synthetic oxytocin administration, and amnioinfusion. Data regarding labor duration by provider type were not available. Maternal composite adverse outcome was positive if either 3rd/4th degree perineal laceration or postpartum hemorrhage occurred (≥ 500ml provider estimated blood loss following vaginal or ≥1000ml blood loss following cesarean birth). Neonatal composite adverse outcome was positive if any one of the following was present: Apgar <7 at 5 minutes, neonatal intensive care (NICU) admission, positive pressure ventilation, or respiratory distress syndrome. A combined maternal and neonatal adverse outcome composite was positive if any one of the maternal or neonatal adverse outcomes was present.

Statistical Analyses

To characterize the entire population, we calculated proportions and unadjusted odds ratios for provider type and birth outcome by maternal, pregnancy, and neonatal characteristics, and labor complications, interventions, and outcomes. Next, we constructed multivariate logistic regression models for unplanned cesarean birth, oxytocin augmentation of labor, neuraxial analgesia in labor, and operative vaginal birth, while adjusting for maternal and pregnancy characteristics that were significantly associated with provider type in unadjusted analysis. We performed all analyses using SPSS (Version 23.0, 2015) with significance set at P< 0.05 for both the Wald chi-square test (coefficient-level significance) and the overall model (likelihood ratio chi-square test).

RESULTS

Among the 22,443 births assessed for inclusion, only 3072 (13.7%) were to healthy, low risk laboring nulliparous women at term gestation with a singleton vertex fetus. Of these, 1339 received care from the prespecified OB (749) and CNM (590) groups (Figure 1). A small group of these low-risk women received care at outlying community clinics and labored with the same provider type who saw them during pregnancy, but subgroup analysis showed no differences in mode of birth for these patients and compared with those assigned to the ‘next available appointment.’ The majority of women in the entire cohort (Table 1) were white, non-Hispanic, and married or partnered. The mean maternal age was 25 years, and 65.7% of women had normal BMI at pregnancy onset. Three-fourths received neuraxial anesthesia during labor, and 10.8% of births were complicated by fever or chorioamnionitis. Half of the women had artificial rupture of membranes, and 41.1% received synthetic oxytocin augmentation, but only 4.3% had amnioinfusion. Most pregnancies (64.7%) ended during the 39th or 40th gestational week, and 94.5% of birthweights were normal. Among vaginal births, 10.3% were by vacuum or forceps. Care was transferred from CNM to OB for 16.8% of all CNM births for either operative vaginal birth (30/590 of CNM births) or cesarean (69/590). There were no transfers from OB to CNM.

Table 1.

Unadjusted odds ratios for maternal, pregnancy, labor, and birth characteristics by provider type in cohort of low-risk laboring nulliparous women, Colorado, United States, 2005–2012

| Factors | Total in Sample n = 1339 |

OB n=749 (55.9) # (%) |

CNM n=590 (44.1) # (%) |

Unadjusted OR and 95% CI for OB Provider Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White | 1009 (75.4) | 587 (78.4) | 422 (71.6) | 1.44 (1.12–1.85) |

| Black | 193 (14.4) | 77 (10.3) | 116 (19.7) | 0.47 (0.34–0.64) |

| Asian/Other | 137 (10.2) | 85 (11.3) | 52 (8.7) | 1.32 (0.92–1.91) |

| Hispanic | 521 (38.9) | 203 (27.1) | 318 (53.9) | 0.32 (0.25–0.40) |

| Married or partnered | 778 (58.1) | 507 (67.7) | 271 (45.9) | 2.47 (1.97–3.08) |

| Maternal age | ||||

| 18–29 years | 1045 (78.0) | 518 (69.2) | 527 (89.1) | 0.27 (0.20–0.36) |

| 30–40 years | 294 (22.0) | 231 (30.8) | 63 (10.7) | 3.73 (2.75–5.06) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal < 25.00 | 880 (65.7) | 512 (68.4) | 368 (62.4) | 1.17 (0.93–1.49) |

| Overweight 25.00–29.99 | 266 (19.9) | 140 (18.7) | 126 (21.4) | 0.80 (0.61–1.05) |

| Obese ≥ 30.00 | 147 (11.0) | 84 (11.2) | 63 (10.7) | 1.01 (0.71–1.40) |

| Missing weight | 46 (3.4) | 13 (1.7) | 33 (5.6) | -- |

| Maternal height ≤ 1.5m (4 ft, 9 in) | 48 (3.6) | 22 (2.9) | 26 (4.4) | 0.66 (0.37–1.17) |

| History of | ||||

| Chronic kidney, liver, or heart disease | 45 (3.4) | 29 (3.9) | 16 (2.7) | 1.45 (0.78–2.69) |

| Other chronic diseasea | 151 (11.3) | 92 (12.3) | 59 (10.0) | 1.26 (0.89–1.78) |

| Psychiatric or psychosocial conditionsb | 97 (7.2) | 45 (6.0) | 52 (8.8) | 0.66 (0.44–1.00) |

|

| ||||

| Pregnancy Characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| During pregnancy | ||||

| Smoked cigarettes | 132 (9.9) | 64 (8.5) | 68 (11.5) | 0.72 (0.50–1.03) |

| Consumed alcohol | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.79 (0.49–12.62) |

| Used illegal drugs | 9 (0.7) | 5 (0.6) | 4 (0.7) | 0.99 (0.26–3.68) |

| Gestational weight gain (pounds) | ||||

| ≤ 10 | 46 (3.4) | 24 (3.2) | 22 (3.7) | 0.82 (0.46–1.48) |

| 11–20 | 137 (10.2) | 74 (9.9) | 63 (10.7) | 0.88 (0.61–1.25) |

| 21–35 | 603 (45.0) | 353 (47.1) | 250 (42.4) | 1.13 (0.91–1.41) |

| 36–40 | 182 (13.6) | 107 (14.3) | 75 (12.7) | 1.09 (0.80–1.50) |

| ≥ 41 | 325 (24.3) | 178 (23.8) | 147 (24.9) | 0.89 (0.69–1.15) |

| Missing weight | 46 (3.4) | 13 (1.7) | 33 (5.6) | -- -- |

| Maternal birth BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 25.00 | 218 (16.3) | 127 (17.0) | 91 (15.4) | 1.12 (0.84–1.50) |

| 25.00–29.99 | 575 (42.9) | 333 (44.5) | 242 (41.0) | 1.15 (0.93–1.43) |

| ≥ 30.00 | 546 (40.8) | 289 (38.6) | 257 (45.6) | 0.81 (0.65–1.01) |

| Gestational age at birth (week-day) | ||||

| 37 0/7–37 6/7 | 94 (7.0) | 60 (8.0) | 34 (5.8) | 1.42 (0.92–2.20) |

| 38 0/7–38 6/7 | 237 (17.7) | 127 (17.0) | 110 (18.6) | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) |

| 39 0/7–39 6/7 | 427 (31.9) | 263 (35.1) | 164 (27.8) | 1.41 (1.11–1.78) |

| 40 0/7–40 6/7 | 440 (32.9) | 235 (31.4) | 205 (34.7) | 0.86 (0.68–1.08) |

| 41 0/7–41 6/7 | 141 (10.5) | 64 (8.5) | 77 (13.1) | 0.62 (0.44–0.88) |

|

| ||||

| Labor Interventions (cont) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Artificial rupture of membranes | 674 (50.3) | 389 (51.9) | 285 (48.3) | 1.16 (0.93–1.44) |

| Neuraxial anesthesia during laborc | 1004 (75.0) | 608 (81.2) | 396 (67.1) | 2.11 (1.64–2.72) |

| Synthetic oxytocin | 550 (41.1) | 331 (44.2) | 219 (37.1) | 1.34 (1.08–1.67) |

| Amnioinfusion | 58 (4.3) | 34 (4.5) | 24 (4.1) | 1.12 (0.66–1.91) |

|

| ||||

| Labor Complications | ||||

|

| ||||

| Maternal fever (>38.0 C) | 115 (8.6) | 71 (9.5) | 44 (7.5) | 1.30 (0.88–1.92) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 144 (10.8) | 89 (11.9) | 55 (9.3) | 1.31 (0.92–1.87) |

|

| ||||

| Birth Outcomes | ||||

|

| ||||

| Neonatal birthweight (kg) | ||||

| Low < 2.5 | 35 (2.6) | 23 (3.1) | 12 (2.0) | 1.53 (0.75–3.10) |

| Normal 2.50–3.99 | 1265 (94.5) | 702 (93.7) | 563 (95.4) | 0.72 (0.44–1.18) |

| High ≥ 4.0 | 36 (2.7) | 22 (2.9) | 14 (2.4) | 1.25 (0.63–2.46) |

| Missing weight | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | -- |

| Vaginal birth (all)d | 1160 (86.6) | 639 (85.3) | 521 (88.3) | 0.77 (0.56–1.06) |

| Operative vaginal delivery (OVD) | 120 (9.0) | 90 (12.0) | 30 (5.1) | 2.68 (1.74–4.13) |

| Cesarean birth (all indications) | 179 (13.4) | 110 (14.7) | 69 (11.7) | 1.30 (0.94–1.79) |

| Fetal intolerance | 69 (5.2) | 43 (5.7) | 26 (4.4) | 1.32 (0.80–2.18) |

| Failure to descend OR labor dystocia (dysfunctional labor) | 110 (8.2) | 67 (8.9) | 43 (7.3) | 1.25 (0.84–1.86) |

Control (reference) group = care with a certified nurse-midwife (CNM), compared to care by an obstetrician (OB)

Bolding denotes statistical significance, p <0.05

Includes mild pulmonary or autoimmune disease, epilepsy or other neurological disorders, sickle cell disease, clotting or bleeding disorders

Psychiatric conditions: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychosis, major depression, panic attacks, post-traumatic stress disorder, autism, suicide attempt, psychiatric hospitalization. Psychosocial conditions: domestic violence, physical assault during pregnancy.

Epidural or combined-spinal epidural

Includes 120 operative vaginal deliveries

The rate of cesarean birth was low (13.4% overall), but consistent with a lower cesarean rate among all women at our institution (25.5%) compared to the U.S. average (>32% during the study timeframe20). Although cesarean birth was more frequent in the last year of data collection (2012), there was no difference by provider type (Supplemental Table 1). The rate of cesarean birth was higher for women who received care from OBs (14.7%) compared to CNMs (11.7%, absolute difference 3.0%, relative difference: 25.6%), but this difference was not significant in unadjusted analyses. The primary indication for cesarean was dysfunctional labor progress (61.5%). In a separate analysis examining characteristics associated with unplanned cesarean birth in our cohort, we confirmed previously reported risks for cesarean, including black race, maternal birth BMI ≥ 30kg/m2, women with gestational ages >41 weeks, neonatal birthweight >4000g, maternal chorioamnionitis, neuraxial anesthesia, oxytocin augmentation, and amnioinfusion (Supplemental Table 2).

Factors Associated with Provider Type in Unadjusted Analysis

Factors associated with provider type in unadjusted analysis are shown in Table 1. Women cared for by OBs were significantly more likely than those cared for by CNMs to be white, married or partnered, and older. Women cared for by OBs were also more likely to receive neuraxial anesthesia and synthetic oxytocin during labor, and to end labor with an operative vaginal birth, but there was no difference in artificial rupture of membranes or amnioinfusion by provider type. Women who received CNM care were significantly more likely to be black, Hispanic, and younger, reflecting the nonrandomized provider assignment by next appointment scheduling or geographic catchment area in our hospital system. Women in the CNM group were also admitted for delivery at later gestational ages (>41 weeks).

Factors Associated with Labor Interventions and Mode of Birth

Adjusting for maternal and pregnancy factors that were significantly associated with provider type in unadjusted analysis (Table 1), unplanned cesarean birth was associated with OB provider type (Table 2). Low-risk, laboring nulliparous women cared for by OBs were 1.48 times more likely to go on to cesarean birth (aOR 1.48, 95% CI [1.04–2.12]) compared to women cared for by CNMs. In addition, among women having vaginal birth, women cared for by OBs were nearly three times more likely than those cared for by CNMs to have an operative vaginal birth (aOR 2.79, 95% CI [1.75–4.44]).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of labor interventions and mode of birth in low-risk nulliparous laboring women cared for by obstetricians (OB) (n=749) compared to certified nurse-midwives (CNM) (n=590), Colorado, United States, 2005–2012

| Predictor: Provider Type | Unadjusted OR and 95% CI for OB Provider Group | Adjusted OR and 95% CI for OB Provider Group |

|---|---|---|

| Labor Interventions | ||

|

| ||

| Neuraxial anesthesia during labor | 2.11 (1.64–2.72) | 1.69 (1.29–2.23) |

| Synthetic oxytocin augmentation | 1.34 (1.08–1.67) | 1.41 (1.10–1.80) |

|

| ||

| Mode of Birth | ||

|

| ||

| Operative vaginal birth (n=1160 vaginal births) | 2.68 (1.74–4.13) | 2.79 (1.75–4.44) |

| Cesarean birth | 1.30 (0.94–1.79) | 1.48 (1.04–2.12) |

Report Odds Ratio (OR) and 95%ile Confidence Intervals (CI).

Bolding denotes statistical significance, p <0.05

Control (reference) group = care with certified nurse-midwife (CNM)

Adjusted models include race-ethnicity, marital status, age, and gestational age.

To evaluate possible reasons for the association between provider type and mode of birth, we examined the association between provider type and labor interventions. In an adjusted model including the same maternal and pregnancy variables used in the mode of birth analysis, women cared for by OBs were more likely to be augmented with oxytocin (aOR 1.41, 95% CI [1.10–1.80]) and to receive neuraxial anesthesia (aOR 1.69, 95% CI [1.29–2.23]) compared to women cared for by CNMs (Table 2).

Adverse Birth Outcomes

We examined unadjusted associations between unplanned cesarean birth and maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes (Table 3). Unplanned cesarean birth was associated with postpartum hemorrhage and all neonatal adverse outcomes. Unplanned cesarean birth was also associated with both composite neonatal and composite overall adverse outcomes. When examined by provider type, none of the maternal or neonatal adverse outcomes were significantly associated with care by a particular type of provider. We then calculated composite adverse outcome scores and examined each against provider type, but saw no significant relationships in unadjusted analyses (Table 3) or in analyses that adjusted for the same maternal and pregnancy variables used in the mode of birth analysis (results not shown).

Table 3.

Unadjusted odds ratios for adverse birth outcomesa by provider type and by mode of birth, Colorado, United States, 2005–2012

| Factors | Total in Sample n =1339 # (%) |

Unplanned Cesarean n=179 (13.4) # (%) |

Vaginal birth n=1160 (66.6) # (%) |

Unadjusted OR and 95% CI for Unplanned Cesarean birth | OB Provider n=749 (55.9) # (%) |

CNM Provider n=590 (44.1) # (%) |

Unadjusted OR and 95% CI for OB Provider Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Maternal Outcomes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Severe perineal lacerationb | 84 (6.3) | -- | 84 (100) | -- | 54 (7.2) | 30 (5.1) | 1.45 (0.92–2.30) |

| Postpartum hemorrhagec | 160(12.0) | 30 (16.8) | 130(11.2) | 1.59 (1.03–2.44) | 95 (12.7) | 65 (11.0) | 1.16 (0.83–1.63) |

|

| |||||||

| Adverse Neonatal Outcomes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Shoulder dystocia | 31 (2.3) | -- | 31 (100) | -- | 20 (2.7) | 11 (1.9) | 1.44 (0.69–3.04) |

| Apgar < 7 at 5 minutes | 28 (2.1) | 10 (5.6) | 18 (1.6) | 3.75 (1.70–8.27) | 11 (1.5) | 17 (2.9) | 0.50 (0.23–1.08) |

| NICU admission in first 24 hours | 66 (4.9) | 19 (10.6) | 47 (4.0) | 2.81 (1.61–4.91) | 36 (4.8) | 30 (5.1) | 0.94 (0.57–1.55) |

| Positive pressure ventilation needed following birth | 62 (4.6) | 19 (10.6) | 43 (3.7) | 3.09 (1.75–5.43) | 33 (4.4) | 29 (4.9) | 0.89 (0.53–1.49) |

| Respiratory Distress Syndrome diagnosis | 44 (3.3) | 14 (7.8) | 30 (2.6) | 3.20 (1.66–6.15) | 24 (3.2) | 20 (3.4) | 0.94 (0.52–1.73) |

|

| |||||||

| Composite Adverse Outcomes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Maternald | 219 | -- | -- | -- | 131 (17.5) | 88 (14.9) | 1.21 (0.90–1.62) |

| Neonatale | 107 (8.0) | 28 (15.6) | 79 (6.8) | 2.54 (1.60–4.03) | 58 (7.7) | 49 (8.3) | 0.93 (0.62–1.38) |

| Overallf | 297(22.2) | 51 (28.5) | 246 (21.2) | 1.48 (1.04–2.11) | 171 (22.8) | 126(21.4) | 1.09 (0.84–1.41) |

Control group = vaginal birth or care with a certified nurse-midwife (CNM)

Bolding denotes statistical significance, p <0.05

There were no cases of maternal or neonatal death-neonatal seizures-neonatal confirmed sepsis-neonatal intracranial hemorrhage-or neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

Severe perineal laceration includes 3rd and 4th degree

For vaginal birth ≥500ml and for cesarean birth ≥1000 ml estimated blood loss

Composite maternal adverse outcome includes severe perineal laceration or postpartum hemorrhage (either one)

Composite neonatal adverse outcome includes Apgar < 7 at 5 min-NICU admission first 24 hr-positive pressure ventilation needed following birth-or diagnosis of respiratory distress syndrome

Overall composite adverse outcome includes all maternal and neonatal outcomes (any one)

DISCUSSION

We found a small group of women comprised the low-risk population of laboring nulliparas with a singleton, vertex fetus (~14%), and that OB care of women in this cohort was associated with increased risk for unplanned cesarean compared to CNM care in adjusted models. Women cared for by OBs had more frequent use of neuraxial anesthesia and oxytocin augmentation. The increased risk of unplanned cesarean in women cared for by OBs compared to those who had CNM care was present despite OB providers’ use of operative vaginal birth more than twice as often as CNMs. Although women cared for by OBs were less likely to be black or at late term gestation (>41 weeks), both independently associated with unplanned cesarean birth,1,28,29 after adjustment, a significant association between OB provider type and cesarean birth, neuraxial anesthesia, oxytocin augmentation, and operative vaginal birth remained. Importantly, the decreased risk of cesarean birth in the CNM group was not at the detriment of adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes, although this study was not powered for those analyses.

The high rate of cesarean birth in the U.S. is a persistent health care quality issue, despite ongoing efforts to increase vaginal births.2 Maternal safety is a key consideration, but retrospective data also suggest that cesarean birth may developmentally alter long term health in offspring. Infants delivered vaginally have reduced risk of respiratory distress syndrome, transient tachypnea of the newborn, type 1 diabetes, and childhood obesity.8–10 Among the healthy laboring nulliparous women in our study, the proportional risk of unplanned cesarean was 25% lower in women managed by CNMs compared with OBs. The optimal total cesarean rate for best maternal and neonatal outcomes is estimated at 10–19%, roughly half the current total U.S. rate.30 Although our data collection (2005–2012) predates publication of national guidelines for labor management to prevent primary cesarean birth,31 our cesarean rate of 13.4% was substantially lower than rates for low-risk women in 2015, after guidelines were published (25.7% in U.S., 20.6% in Colorado).1 Since adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes were significantly associated with cesarean birth as seen in other studies6 and not with provider type, labor and birth models that increase CNM care for low risk women may most favorably balance the competing issues of maternal and neonatal risk during childbirth.

The protective influence of CNM provider type on the risk of unplanned cesarean birth in low-risk women has been reported in other countries, and in some U.S. observational studies.15,32,33 Collaborative practice between CNMs and OBs is proposed as a strategy for high-quality, cost-efficient pregnancy care,14 and our study supports that model. In order to accurately characterize the contribution of provider type and intrapartum management to unplanned cesarean, high quality controlled trials in the U.S. are warranted. Recognizing that it may be difficult to enroll women in trials that decrease their autonomy in provider choice, such studies may not be feasible. Alternatively, trials comparing the effects of different bundles of prenatal or intrapartum care on birth outcomes by all providers could be used to guide U.S. pregnancy care. Health services investigations are also needed that contrast different models of care, unit protocols, and care guideline implementation at the hospital and system levels.

Our finding that neuraxial anesthesia and labor augmentation with synthetic oxytocin were significantly associated with cesarean birth and in adjusted analysis with provider type has implications for clinical practice by all provider types. In our dataset, we were unable to determine if oxytocin augmentation or neuraxial anesthesia was associated with shorter labors. However, it is possible that more strict definitions of labor arrest disorders than are recommended today31 may have altered provider expectations for labor progress and patterns of labor intervention use when our data was collected. We were also unable to ascertain how the order of these interventions may have changed labor progress or risk for cesarean birth. Finally, we could not examine how maternal characteristics associated with cesarean birth (race, ethnicity, marital status, age, and gestational age) may have changed labor progress. However, given our finding that maternal characteristics were more important than provider type in predicting birth outcomes, perhaps care by midwives is especially important for nulliparous laboring women with maternal risk factors for cesarean birth.34

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has a number of strengths, including a large cohort from which we selected a low-risk sample, prospective collection of both maternal and neonatal data, and intention-to-manage analysis. We analyzed associations between provider type and an extensive list of maternal and pregnancy characteristics known to predict labor difficulty,13,22,28,29 and included any maternal characteristic found to be significantly related to provider type in all adjusted models. Further, we chose to examine only laboring women because we conjectured that labor management choices might show the greatest effect in women who did not initially require labor induction.

Selection bias was reduced by excluding those women who we knew self-selected CNM care from a private group. There was no loss to follow-up, as data were collected around the admission for labor and birth. Women in this study gave birth with different providers within a single institution during the same time period, eliminating confounding due to highly variable institutional or chronological factors. Furthermore, the robust CNM practice in this hospital made comparisons by provider type less likely to be dominated by a predominant provider culture.

The study has some limitations. First, this is a retrospective investigation, and there may be unidentified enrollment bias. We cannot identify women in this sample who may have self-selected provider type, though this is a rare occurrence for these low-risk nulliparous women in our system, who are typically assigned to providers non-systematically or by the geographic catchment area of their community prenatal clinic. We had no data for the unknown number of women who started prenatal care within our system but ultimately delivered at another hospital. We were unable to discriminate the effect of prenatal care versus intrapartum management by provider type. Next, although we met our a priori sample number, the lower overall cesarean birth rate at our institution limited the study power. Post-hoc power calculation using the actual rates of unplanned cesarean in this cohort was 0.6; a total of 999 subjects per group would be required for 80% power and p<0.05. This study was not powered to detect adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes by provider type, and we have no long-term information on maternal or neonatal outcomes. Finally, although we collected data for many characteristics, important labor management variables (e.g., intravenous antibiotic dosing, total dose and duration of synthetic oxytocin administration, labor duration) were not available.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings suggest that provider type, vis a vis intrapartum management style, is an important potentially modifiable factor to reduce unplanned cesarean birth in low-risk, laboring nulliparous women. The U.S. health care systems could benefit by more fully incorporating CNM-OB collaborative models of care to possibly decrease cesarean rates in nulliparous women. Further investigation with high quality trials of maternity care models in the U.S. is needed to understand how provider practices contribute to the overall cesarean rate and thereby influence acute and long term outcomes for women and their offspring.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING/SUPPORT: National Institutes of Health (1F31NR014061) and March of Dimes (NSC), UCDenver WRHR #2K12HD001271 and sMFM-AAOGF Scholar Award (KJH).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF INTERESTS: All authors report no conflict of interest

Contributor Information

Nicole S. Carlson, Emory University Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, 1520 Clifton Road NE, Atlanta GA 30322.

Elizabeth J. Corwin, Emory University Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, 1520 Clifton Road NE, Atlanta GA 30322.

Teri L. Hernandez, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, & Diabetes and College of Nursing, 12801 E. 17th Ave, MS 8106 Aurora CO 80045.

Elizabeth Holt, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Reproductive Sciences, 12700 East 19thAve, MS 8613, Aurora CO 80045.

Nancy K. Lowe, University of Colorado College of Nursing, 13120 East 19th Ave, MS C288, Aurora, CO 80045.

K. Joseph Hurt, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Maternal Fetal Medicine & Reproductive Sciences, 12700 East 19th Ave, MS 8613, Aurora CO 80045.

References

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJ. Births: Preliminary Data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(3):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Joint Commission. Specifications Manual for Joint Commission National Quality Measures. Perinatal Care 02 (v2016A) 2016 https://manual.jointcommission.org/releases/TJC2016A/MIF0167.html.

- 3.Osterman MJ, Martin JA. Trends in low-risk cesarean delivery in the United States, 1990–2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(6):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber EL, Lundsberg LS, Belanger K, Pettker CM, Funai EF, Illuzzi JL. Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):29–38. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821e5f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kozhimannil KB, Law MR, Virnig BA. Cesarean delivery rates vary tenfold among US hospitals; Reducing variation may address quality and cost issues. Health Affairs. 2013;32(3):527–535. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark EA, Silver RM. Long-term maternal morbidity associated with repeat cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(6 Suppl):S2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1226–1232. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000219750.79480.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farchi S, Di Lallo D, Franco F, et al. Neonatal respiratory morbidity and mode of delivery in a population-based study of low-risk pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(6):729–732. doi: 10.1080/00016340902818154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black M, Bhattacharya S, Philip S, Norman JE, McLernon DJ. Planned Cesarean Delivery at Term and Adverse Outcomes in Childhood Health. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2271–2279. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhle S, Tong OS, Woolcott CG. Association between caesarean section and childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):295–303. doi: 10.1111/obr.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khashan AS, Kenny LC, Lundholm C, Kearney PM, Gong T, Almqvist C. Mode of obstetrical delivery and type 1 diabetes: a sibling design study. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e806–813. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990–2014. PloS one. 2016;11(2):e0148343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle A, Reddy UM. Epidemiology of cesarean delivery: The scope of the problem. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36(5):308–314. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:Cd004667. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman MR, Murphy SM, Fitzgerald CE, Andersen HF, Daratha KB. The cost of nurse-midwifery care: Use of interventions, resources, and associated costs in the hospital setting. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(4):434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayes F, Oakley D, Wranesh B, Springer N, Krumlauf J, Crosby R. A retrospective comparison of certified nurse-midwife and physician management of low risk births. A pilot study. J Nurse Midwifery. 1987;32(4):216–221. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(87)90113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis LG, Riedmann GL, Sapiro M, Minogue JP, Kazer RR. Cesarean section rates in low-risk private patients managed by certified nurse-midwives and obstetricians. J Nurse Midwifery. 1994;39(2):91–97. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nijagal MA, Kuppermann M, Nakagawa S, Cheng Y. Two practice models in one labor and delivery unit: association with cesarean delivery rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(4):491.e491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Declercq E. Midwife-Attended Births in the United States, 1990–2012: Results from Revised Birth Certificate Data. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2015;60(1):10–15. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenstein M, Nakagawa S, King TL, Frometa K, Gregorich S, Kuppermann M. 154: The association between adding midwives to labor and delivery staff and cesarean delivery rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1, Supplement):S100. [Google Scholar]

- 21.American College of O, Gynecologists. ACOG Committee opinion no. 549: Obesity in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):213–217. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000425667.10377.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu SY, Kim SY, Schmid CH, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of cesarean delivery: A meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2007;8(5):385–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284–2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. The international classification of adult underweight, overweight and obesity according to BMI. 2016 http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

- 25.Kominiarek M, Vanveldhuisen P, Hibbard J, et al. The maternal body mass index: A strong association with delivery route. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(3):264.e261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roloff K, Peng S, Sanchez-Ramos L, Valenzuela GJ. Cumulative oxytocin dose during induction of labor according to maternal body mass index. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(1):54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lassiter JR, Holliday N, Lewis DF, Mulekar M, Abshire J, Brocato B. Induction of labor with an unfavorable cervix: How does BMI affect success? J Matern Fetal Med. 2016;29(18):3000–3002. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1112371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tita AT, Lai Y, Bloom SL, et al. Timing of delivery and pregnancy outcomes among laboring nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):239.e231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Min CJ, Ehrenthal DB, Strobino DM. Investigating racial differences in risk factors for primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):814.e811–814.e814. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molina G, Weiser TG, Lipsitz SR, et al. Relationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal Mortality. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2263–2270. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spong CY, Berghella V, Wenstrom KD, Mercer BM, Saade GR. Preventing the first cesarean delivery: Summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1181–1193. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e3182704880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thiessen K, Nickel N, Prior HJ, Banerjee A, Morris M, Robinson K. Maternity outcomes in Manitoba women: A comparison between midwifery-led care and physician-led care at birth. Birth. 2016;43(2):108–115. doi: 10.1111/birt.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenstein MG, Nijagal M, Nakagawa S, Gregorich SE, Kuppermann M. The association of expanded access to a collaborative midwifery and laborist model with cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):716–723. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw-Battista J, Fineberg A, Boehler B, Skubic B, Woolley D, Tilton Z. Obstetrician and nurse-midwife collaboration: Successful public health and private practice partnership. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):663–672. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822ac86f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.