Abstract

Purpose

Hyperpolarized 13C metabolic imaging is a non-invasive imaging modality for evaluating real-time metabolism. The purpose of this study was to develop and implement experimental strategies for using [1-13C]pyruvate to probe in vivo metabolism for patients with brain tumors and other neurological diseases.

Methods

The 13C RF coils and pulse sequences were tested in a phantom and were performed using a 3T whole body scanner. Samples of [1-13C]pyruvate were polarized using a SPINlab system. Dynamic 13C data were acquired from eight patients previously diagnosed with brain tumors, who had received treatment and were being followed with serial MR scans.

Results

The phantom studies produced good quality spectra with a reduction in signal intensity in the center due to the reception profiles of the 13C receive coils. Dynamic data obtained from a 3 cm slice through a patient’s brain following injection with [1-13C]pyruvate showed the anticipated arrival of the agent, its conversion to lactate and bicarbonate, and subsequent reduction in signal intensity. A similar temporal pattern was observed in 2D dynamic patient studies, with signals corresponding to pyruvate, lactate and bicarbonate being in normal appearing brain but only pyruvate and lactate being detected in regions corresponding to the anatomic lesion. Physiological monitoring and follow-up confirmed that there were no adverse events associated with the injection.

Conclusions

This study has presented the first application of hyperpolarized 13C metabolic imaging in patients with brain tumor and demonstrated the safety and feasibility of using hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate to evaluate in vivo brain metabolism.

Keywords: Dynamic nuclear polarization, hyperpolarized carbon-13 MRI, brain tumor patients

INTRODUCTION

Hyperpolarized carbon-13 (13C) magnetic resonance (MR) metabolic imaging is a non-ionizing, non-radioactive imaging method that can be used to measure real-time metabolism. The recent development of dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) offers an exciting method for assessing in vivo metabolism, with a huge gain in signal intensity over the conventional 13C MR methods (1) and enables the acquisition of 13C metabolic imaging data with high spatial resolution in a short time (2). One of the first applications of this technology has been to evaluate the conversion of [1-13C]pyruvate to [1-13C]lactate. This is particularly relevant for monitoring tumor growth and assessing response to therapy because malignant cells frequently have up-regulated lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), which is the enzyme that regulates this pathway (3, 4). Pre-clinical studies that have shown promising results include the assessment of a wide range of different cancers, as well as cardiac disease, traumatic brain injury and multiple sclerosis (5–13).

The first-in-human study using hyperpolarized 13C metabolic imaging was performed in patients with prostate cancer and was able to demonstrate the safety and feasibility of the technology in a clinical setting (14). This has led to great interest in applying similar methods to other groups of patients and also for volunteer cardiac studies (15). The purpose of the current study was to develop and implement hyperpolarized 13C metabolic imaging using [1-13C]pyruvate in the human brain, with the long term goal of being able to monitor in vivo metabolism for patients with brain tumors and other neurological diseases. The 13C coils and pulse sequences designed for this application were first tested in phantoms. Dynamic 13C data were then obtained from patients with a prior diagnosis of glioma, which is the most common primary brain tumor in adults.

METHODS

13C MR Setup

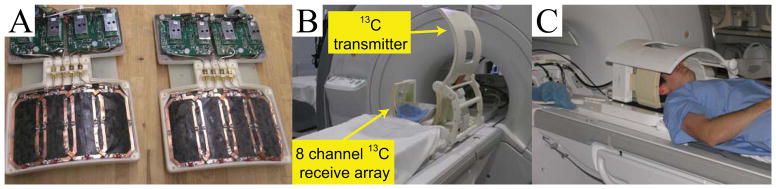

All experiments were performed using a 3 Tesla (T) clinical MRI system (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) with 50 mT/m, 200 mT/m/ms gradients, and a multinuclear spectroscopy (MNS) hardware package. The 13C radiofrequency (RF) coil configuration comprised a bore-insertable 13C volume coil for transmission (16) and a bilateral 8-channel phased-array coil for reception (17) (Figure 1A and 1B). The standard patient head rest holder was modified so that the subjects were comfortably stabilized in the 13C RF coil setup, while the two phased-array receive coils were placed around the head (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

13C RF coil configurations developed for human brain study. (A) 8-channel 13C phased array coils. (B) Clamshell volumetric 13C transmit coil and bilateral eight-channel phased array receive coils. (C) A picture of 13C RF coil setup with a volunteer.

13C Coil Loading Tests

To investigate the effect of coil loading on the 13C signal, a B1+ map was acquired using the double angle method (18) in both unloaded and loaded scenarios using a head shaped phantom containing unenriched ethylene glycol (HOCH2CH2OH, anhydrous, 99.8%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). To acquire the B1+ map, a single-band spectral-spatial RF pulse (FWHM=120 Hz) was used to selectively excite the central 13C resonance of ethylene glycol and avoid artifacts arising from chemical shift, and then encoded with a single-shot symmetric echo-planar readout (19). The total readout duration was 15.46ms (24 echoes, 0.644ms echo spacing), with α=30°, 2α=60°, and 100 averages (7.5x7.5 mm in-plane resolution, 24x24 cm FOV, 32x32 matrix, 10 cm slice thickness, repetition time(TR)/echo time(TE)=3000/15.6ms, the total scan time was 10 min). The B1 map was acquired unloaded (with just the head phantom) and loaded (with the head phantom plus saline). Loading was confirmed with a change from −7dB to −11dB using a network analyzer. The flip angles over the ethylene glycol phantom were assessed as grey-scale maps and histograms, and compared between the loaded and unloaded cases.

Phantom Tests

The phantom was scanned using the clamshell/phased array coil configuration shown in Figure 1. For these scans, the distance between the center of the two receive coils was 17 cm. 13C spectral data were acquired from a 2 cm slice using a dynamic 13C 2D echo-planar spectroscopic imaging (EPSI) sequence with TR/TE=3000/6.1ms, 20x20 mm2 nominal in-plane resolution (20), 10 phase encodes in the RL direction and a symmetric echo-planar readout in the AP direction with a constant 90° flip angle excitation.

Patient population

Eight patients who had a prior diagnosis of glioma were recruited from the neuro-oncology clinic at our institution. Table 1 summarizes their clinical parameters. They had all received multiple treatments and were being followed with MR imaging. An Investigational New Drug (IND) had been obtained from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for generating the agent and implementing the clinical protocol. Patients provided written informed consent for participation in the study which had institutional review board (IRB) approval. Electrocardiogram monitoring was performed at baseline and within 1 hour after the pyruvate injection. Clinical follow-up assessments were performed at 24 hours.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and QC values for the 13C injections. OD2 = oligodenroglioma grade 2, OD3 = oligodendroglioma grade 3, AA = anaplastic astrocytoma (grade 3), GBM = glioblastoma (grade 4), TE = treatment effect, EPA = electron paramagnetic agent.

| Patient # | Sex | Weight (kg) | Initial diagnosis age (years) | Time to scan (years)* | Current diagnosis | Subsequent clinical status | EPA conc (μM) | pyr conc (nM) | % polarization | pH | Time to injection (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| 1 | M | 81.4 | 35 | 19 | OD2 | stable | 0.50 | 247 | 33 | 7.3 | 81 |

| 2 | M | 73.5 | 30 | 8 | GBM | progressed | 1.40 | 236 | 38 | 7.5 | 84 |

| 3 | M | 75.8 | 38 | 6 | OD2 | reop/AA | 0.30 | 223 | 39 | 8.1 | 114 |

| 4 | M | 93.0 | 25 | 12 | AA | reop/AA | 3.00 | 221 | 43 | 7.8 | 86 |

| 5 | F | 81.2 | 58 | 2 | GBM | progressed | 1.30 | 249 | 43 | 7.0 | 96 |

| 6 | M | 99.4 | 36 | 12 | OD3 | stable | 0.90 | 239 | 32 | 7.4 | 85 |

| 7 | F | 65.0 | 46 | 2 | GBM | reop/TE | 0.20 | 232 | 33 | 7.9 | 74 |

| 8 | F | 78.0 | 54 | 1 | GBM | stable | 0.30 | 242 | 35 | 7.2 | 87 |

Time from initial diagnosis to the 13C scan

Sample Formulation and Polarization

For patients scans, the hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate was produced using a SPINlabTM (General Electric, Niskayuna, NY) DNP polarizer that is adjacent to the 3 T MR scanner. The pharmacy kit (fluid path) was filled in an ISO 5 environment utilizing an isolator (Getinge Group, Getinge, France) and a clean bench laminar flow hood. The mixture used for polarization comprised 1.432g of [1-13C]pyruvic acid (MilliporeSigma, Miamisburg OH) and 28 mg of trityl radical (GE Healthcare, Oslo, Norway). The fluid path was then loaded into one of the available channels in the SPINlab polarizer. After approximately 2.5 hours of microwave irradiation at 140 GHz, the mixture of [1-13C]pyruvic acid and trityl radical was dissolved in sterile water and forced through a filter that removed trityl radical to a level below 3 μM. The solution was then collected in a receiver vessel, neutralized and diluted with a sodium hydroxide TRIS/EDTA buffer solution. The receive assembly that accommodates quality control (QC) processes, provided rapid measurements of pH, temperature, residual EPA concentration, volume, pyruvate concentration and polarization level. The final step in the automated compounding procedure was for the drug product to be passed through a sterilizing filter (0.2 μm; ZenPure) within the SPINlab QC system immediately before being collected in a sterile Medrad syringe.

Once the preparation was complete, a sterile filter integrity test was performed in parallel with the pyruvate solution being transported to the MRI scan room and being setup on a power injector. Successful QC and filter integrity tests were required before the hyperpolarized pyruvate doses were released for patient injections. The acceptance criteria for the hyperpolarized pyruvate injection were: 1) polarization >= 15%; 2) pyruvate concentration between 220 and 280 mM; 3) EPA concentration <= 3.0 μM; 4) pH between 5.0 and 9.0; 5) temperature between 25.0 and 37.0 °C; 6) volume > 38 mL; 7) filter integrity passes the bubble point test at 50 psi. Following approval from the pharmacist, a sample corresponding to a dose of 0.43 mL/kg from the approximately 250 mM pyruvate solution was delivered to the subject at a rate of 5 mL/s. After completion of pyruvate injection, a further 20 mL of sterile saline was injected at a rate of 5 mL/s. The polarization, QC, and timing parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Imaging Protocol for Patient Study

Before the start of each examination, the patients were monitored to establish their baseline vital signs and an intravenous catheter was placed in their antecubital vein. After positioning in the scanner with the 13C coil set-up covering as much of the lesion as possible, T2-weighted fast spin echo (FSE) images (TR/TE=60/4000ms, 26 cm FOV, 192x256 matrix, 5 mm slice thickness and 2 NEX) were acquired with the 1H body coil to provide an anatomic reference. Frequency calibration was performed with the 13C coils using the sealed standard that is housed within one of the 8-channel phased array elements and contains 1 mL of 8 M 13C-urea. Once the appropriate scan parameters had been defined, the operators of the SPINlab system started the dissolution process. When the pharmacist had approved the results provided by the QC system and filter integrity tests, the pyruvate solution and saline flush were administered into the patient. Dynamic 13C data were acquired starting 5s after the end of the saline injection from an axial slab that was centered over the anatomical lesion.

The acquisition parameters for the 13C data are summarized in Table 2. For patient 1, the dynamic data were acquired from a 30 mm axial slice with a 10° flip angle, TR/TE=3000/35ms, 3s temporal resolution and 40 total time points. For 5 patients, 2D-localized dynamic EPSI data were obtained from a 20 mm axial slice with a constant 10° flip angle, 24 total time points, either 10 or 12 phase encodes in the RL direction and a symmetric echo-planar readout in the AP direction (20). The TR/TE was 130/6.1ms, the time resolution was 3s and the nominal in-plane spatial resolution was either 15x15, 18x18 or 20x20 mm2 (21). The EPSI readout contained the following parameters: spectral resolution=10.4 Hz, EPSI duration=96.4 ms, spectral bandwidth=543 Hz, minimum resolution=4.8 mm, SNR efficiency=0.94. Similar dynamic EPSI data were obtained for the other 2 patients, but with an excitation scheme that utilized a multi-band RF pulse and progressively increasing flip angle scheme (22, 23). These flip angle schemes were designed to efficiently use the magnetization in several ways: use lower flip angles on pyruvate to increase the magnetization available for metabolic conversion, evenly distribute magnetization throughout the acquisition by accounting for T1 decay, prior RF excitations, and metabolic conversion; and use all available magnetization by the end of the experiment (23). The plot of pyruvate, lactate and bicarbonate flip angles across all excitations are shown in Supporting Figure S1. At the completion of the 13C examination, patients were taken out of the scanner for post-injection monitoring and then brought back for a subsequent standard 1H MR examination that was obtained with a conventional head coil.

Table 2.

Summary of the acquisition parameters for the patient 13C data, as well as the time point and SNR for maximum pyruvate and lactate. All studies were acquired with a temporal resolution of 3s. lac and pyr represent lactate and pyruvate, respectively.

| Patient # | Scan type† | Flip angle (°) | Number of time points | Voxel size (RLxAPxSI cm) | Matrix size§ | Peak time point (s) | Delay | Maximum SNR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| pyr | lac | Δt (s) | pyr | lac | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | Slice-select | 10 | 40 | 3 cm slice | - | 15 | 24 | 9 | 3266 | 293 |

| 2 | 2D EPSI | 10 | 24 | 2x2x2 | 10x18 | 6 | 15 | 9 | 754 | 103 |

| 3 | 2D EPSI | 10 | 24 | 2x2x2 | 10x18 | 9 | 18 | 9 | 286 | 38 |

| 4 | 2D EPSI | 10 | 16 | 2x2x2 | 10x18 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 665 | 53 |

| 5 | 2D EPSI | 10 | 24 | 1.8x1.8x2 | 10x18 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 714 | 38 |

| 6 | 2D EPSI | 10 | 24 | 1.5x1.5x2 | 12x18 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 388 | 25 |

| 7 | 2D EPSI-mb | variable | 10 | 2x2x3 | 10x18 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 119 | 83 |

| 8 | 2D EPSI-mb | variable | 10 | 2x2x2 | 10x18 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 169 | 91 |

Slice-select, 2D EPSI and 2D EPSI-mb represent slice-selective dynamic, 2D-localized dynamic echo-planar spectroscopic imaging and multi-band RF 2D-localized dynamic echo-planar spectroscopic imaging pulse sequence, respectively.

Matrix size in phase encode (RL) x EPSI (AP) directions.

Data Analysis

The slice-localized dynamic 13C data were processed with MATLAB 7.0 (Mathworks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts). Individual free induction decays (FIDs) were apodized with a 10 Hz Gaussian filter in the time domain and Fourier-transformed to produce 13C spectra at each time point. The 2D EPSI dynamic 13C data were processed with software developed in our laboratory including the Spectroscopic Image Visualization and Computing (SIVIC) package (24, 25). The odd and even echoes of the symmetric EPSI readout were separated and processed by the following steps: (1) apodization by a 10 Hz Gaussian filter in the time domain, (2) correction of timing delays between spatial k-space samples, (3) ramp samples were gridding onto a uniform grid, (4) Fourier-transformed, and (5) combined with linear phase added to correct for timing differences between the even and odd data. This produced a time series of spectroscopic imaging data for each coil element. In order to correct for the aliased bicarbonate chemical shift, the second set of data were generated by demodulating the raw data at a different frequency prior to reconstruction. The coil combination algorithm used for the slice select and initial review of the 2D EPSI data employed a magnitude sum of squares algorithm. Subsequent quantitative analysis of the 2D EPSI data utilized a linear combination of phase sensitive spectra from different receive coils with phases and weights determined from the intensity of the pyruvate signal from the time point at which it was at a maximum. In addition to the dynamic analysis, a single spectral array was calculated by summing the time series on a voxel by voxel basis. Peak intensities for lactate and pyruvate were estimated from the spectral array that was reconstructed at the original reference frequency and the peak intensities for bicarbonate were estimated from the array that was reconstructed at its frequency. To perform this analysis, each array was baseline subtracted, frequency and phase corrected using methods described previously for H-1 data (25). The signal-to-noise-ratios (SNR) were calculated as the peak height over the standard deviation from regions in the spectra without any metabolic signal.

To relate the 13C data with anatomic features, the fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T1-weighted post-Gd images obtained from the subsequent 1H imaging examination were aligned with the body coil T2-weighted images. A mask corresponding to brain parenchyma was obtained using the FSL brain extraction tool. The T2 lesion was defined using manual segmentation. This was then subtracted from the mask of brain parenchyma in order to unambiguously define regions of normal appearing brain (NAB) tissue. The following criteria were used to classify the voxels for NAB or T2 lesion: 1) Voxels from NAB were defined as being at least 80% within the brain, having no overlap with the T2 lesion and having lactate SNR greater than 10.0 and bicarbonate SNR greater than 5.0; 2) for the T2 lesion, the voxels that were overlapped by more than 30% with the T2 lesion and had lactate SNR greater than 10.0 were chosen.

RESULTS

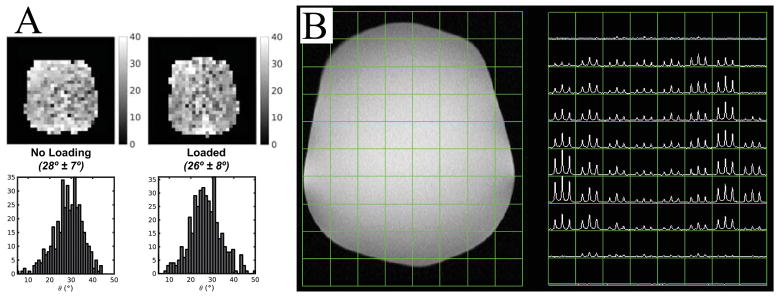

13C Coil Loading Test

Figure 2A shows the results from the 13C coil loading test. The B1+ field measured using the double flip angle method (26) appeared to be similar between the unloaded and loaded conditions. The calculated flip angles from the flip angle maps and histograms were 28° ± 7° (n=3) and 26° ± 8° (n=3) for the unloaded and loaded condition, respectively. This meant that the power requirements did not change between the loaded and unloaded conditions, and a power calibration on the head phantom could be used for patient studies. Based on these results, the ethylene glycol phantom shown was used to calibrate the transmit gain for the 13C sequence before subjects were placed on the scanner.

Figure 2.

Results from the 13C coil loading and initial data acquisition tests. (A) B1+ maps of flip angle were calculated using a double flip angle method and showed that the B1 maps were similar between the unloaded and loaded conditions. (B) 2D EPSI data from the head-shaped phantom containing ethylene glycol demonstrated the combined reception profile of the receive coils.

Phantom Data

The 13C coils and sequences detected 13C signal from the phantom (Figure 2B) but with 3–4 fold lower intensity in the center of the field of view due to the reception profiles of the receive coil elements. This is in agreement with previous tests done in a study that focused on evaluating data from the brain of a non-human primate (21).

Patient Data

All patients tolerated the pyruvate injection well and no adverse effects were observed or reported subsequently. The levels of polarization and QC parameters obtained are presented in Table 1 and were well within the specifications defined in the IND. The mean EPA concentration was 0.99 μM (range 0.2 to 3), pyruvate concentration was 236 mM (range 221 to 249), polarization was 37% (range 32 to 43), pH was 7.5 (range 7.0 to 8.1). The mean scan start time measured from the start of dissolution was 88 s (range 74 to 114).

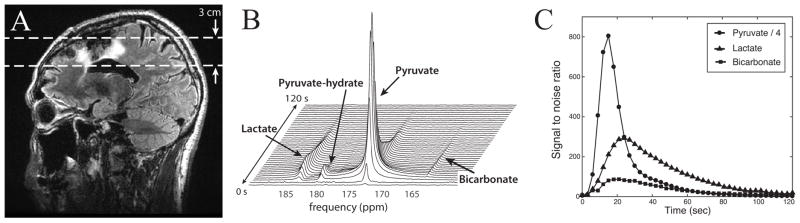

Figure 3 shows the slice-localized 13C dynamic data from a 30 mm-thick axial slice for subject 1. The location of the slice is defined on the sagittal image in Figure 3A. The 13C dynamic spectra are represented as a stack plot in Figure 3B. They are displayed in magnitude mode and were acquired with a time resolution of 3s. The SNR of pyruvate, lactate and bicarbonate are plotted as a function of time in Figure 3C. The pyruvate signal at 173 ppm reached a maximum with SNR of 3266 at approximately 15s from the start of the data acquisition, while the lactate signal at 185 ppm reached a maximum SNR of 293 at 24s, which was 9s later. The pyruvate signal decreased rapidly from the maximum peak. Pyruvate–hydrate was observed as a peak lying between the pyruvate and lactate resonances, but had relatively low signal amplitude (Figure 3B). Signal from bicarbonate was detected at approximately 162 ppm and had lower intensity than lactate (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Slice-localized hyperpolarized 13C dynamic data from patient 1. (A) T2 FLAIR image in a sagittal plane shows the hyperintense region around the resection cavity and the ventricle. (B) The stack plot of 13C magnitude spectra, showing a temporal evolution of lactate, pyruvate and bicarbonate signal from the brain. (C) The SNR of lactate, pyruvate, urea and bicarbonate are plotted over time. The pyruvate SNR was divided by 4 so that it could be viewed on the same graph as the pyruvate and bicarbonate.

The peak time point and maximum voxel SNR for the 2D EPSI dynamic data are shown in Table 2. Although the time at which the pyruvate delivery was a maximum varied from 3s to 9s, the additional delay for reaching the highest lactate was 9s for 6 of the 7 patients and 6s for 1 patient. As expected, the maximum SNRs was lowest for patient 3, for whom the time to injection was the longest at 114s, and the second lowest for patient 6, for whom the number of phase encodes was increased and the voxel resolution reduced. The maximum SNR for pyruvate was lower in patients 7 and 8 due to the multiband excitation and flip angle scheme that was used but this scheme resulted in higher levels of lactate and bicarbonate. Taken as a whole, these results confirmed that hyperpolarized pyruvate was able to cross the blood brain barrier and was converted to lactate with a similar time course between subjects.

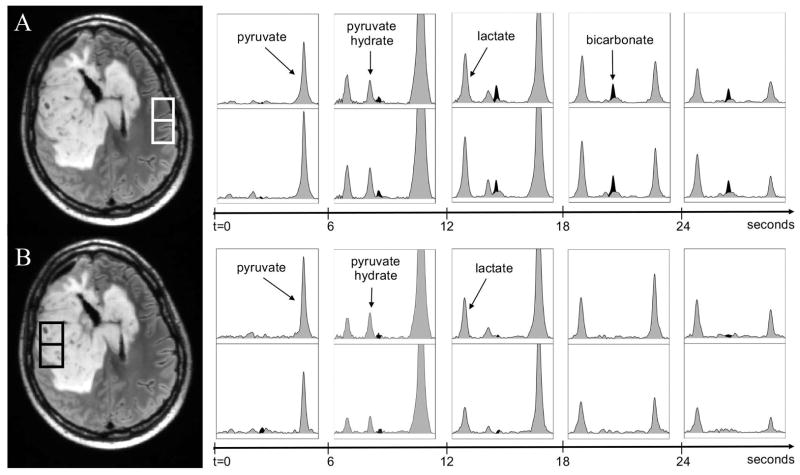

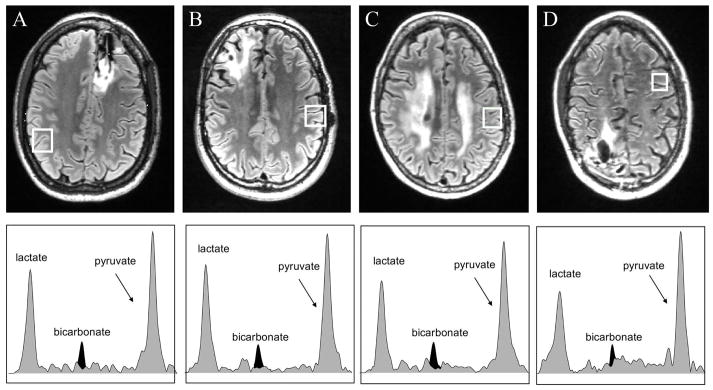

The acquisition of the 2D EPSI dynamic 13C metabolic imaging data made it possible to investigate spatial variations in metabolism. Figure 4 shows reference anatomic images and spectra from multiple time points for voxels in the T2 lesion (black box) and voxels from contralateral brain tissue (white box) for patient 2. The voxels from the T2 lesion show peaks from lactate, pyruvate-hydrate and pyruvate, while the voxels from contralateral NAB have peaks from lactate, pyruvate-hydrate, bicarbonate and pyruvate. Note that because of the reduced spectral bandwidth with EPSI the bicarbonate peak wrapped into a location between pyruvate-hydrate and pyruvate peaks (~179 ppm). In both cases lactate peaks were relatively high in the time period between 12s and 24s after the start of data acquisition. The spectra in Figure 5 are from voxels in NAB for patients 3 to 6 at time points where the lactate was highest. While it is difficult to compare intensities due to variations in the reception profile of the coil, it can be seen that the relative levels of lactate and pyruvate were similar to those for patient 2 but that the bicarbonate peak is absent for the spectrum from patient 6. This may be due to the smaller voxel size and the use of 12 rather than 10 phase encodes for data acquisition.

Figure 4.

Temporal changes in spectra from the highlighted voxels in (A) normal appearing brain and (B) the T2 lesion from patient 2. The spectra with peaks shaded in gray are from the data reconstructed at the acquired reference frequency and the peaks shaded in black represent the data reconstructed at the bicarbonate frequency. The spectra shown are from time at 0s, 6s, 12s, 18s and 24s from the start of data acquisition. The highest pyruvate and pyruvate-hydrate occur at 6s, while the highest lactate occurs at time point 15s. It can be seen that there are lactate and bicarbonate peaks in normal appearing brain and lactate peaks in the T2 lesion during the period of 9s to 24s. The chemical shift range is 186.46 to 169.61ppm for all spectroscopic voxels. The intensity scales are arbitrary, but were kept the same for all spectra.

Figure 5.

FLAIR images and spectra in the highlighted normal appearing brain voxels at time with maximum lactate from (A) patient 3, (B) patient 4, (C) patient 5 and (D) patient 6. The spectra with peaks shaded in gray are from the data reconstructed at the acquired reference frequency and the peaks shaded in black represent the data reconstructed at the bicarbonate frequency. The relative levels of pyruvate are similar but the lactate is slightly lower in all patients shown and the bicarbonate is not detectable for patient 6, for whom the acquisition had the smallest voxel size 1.5x1.5x2 cm and 12 rather than 10 phase encodes. The chemical shift range is 186.46 to 169.61ppm for all spectroscopic voxels. The intensity scales are arbitrary, and were manually set to have similar pyruvate intensity levels between subjects.

Table 3 shows metabolite intensities and ratios for spectra from patients 2 to 8 that were summed over all time points. In all cases, the maximum lactate and bicarbonate SNRs were higher in the NAB than in the T2 lesion. Of particular interest is that the 2 patients whose data were acquired with the multi-band variable flip angle excitation scheme (patient 7 and 8) have much higher maximum SNR for bicarbonate in NAB (28.8 and 34.1) than patients 2 to 6 but, even in this case, the maximum SNR of bicarbonate from the T2 lesion was close to or lower than the level considered to be detectable (4.0 and 5.4). The maximum SNR of lactate in the T2 lesion was variable between patients, which reflects not only differences in its location relative to the sensitivity profile of the RF coils but also due to differing contributions from tumor versus treatment effects. The mean lactate/pyruvate for voxels in NAB that had sufficient SNR to provide good estimates of metabolite levels for patients 2–6 ranged from 0.18 to 0.38, while for patients 7 and 8 they were 0.98 and 0.84. The corresponding values for bicarbonate/pyruvate were 0.06 to 0.15 versus 0.32 and 0.37. The increased metabolite ratios in patients 7 and 8 are likely a result of the multiband variable flip angle scheme used only in these patients.

Table 3.

Maximum SNR of metabolites from the summed spectra and ratios of lactate/pyruvate and bicarbonate/pyruvate. Maximum SNR and mean ratios are from voxels that were either: normal appearing brain (NAB) - at least 80% from NAB, not overlapping with the T2 lesion and with lactate SNR>10.0 and bicarbonate SNR>5.0; or T2 lesion - overlapped by more than 30% with the T2 lesion with lactate SNR>10.0 (n= number of voxels satisfying criteria). Note that the multi band, variable flip angle scheme used for Patient 7 & 8 will alter the metabolite ratios. lac, bicarb and pyr represent lactate, bicarbonate and pyruvate, respectively.

| Patient # | Max SNR: NAB | Max SNR: T2 lesion | Mean ratios: NAB | Mean ratios: T2 lesion | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| lac | bicarb | lac | bicarb | n | lac/pyr | n | bicarb/pyr | n | lac/pyr | n | bicarb/pyr | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 2 | 77.7 | 30.4 | 51.6 | 2.0 | 12 | 0.38 | 12 | 0.15 | 8 | 0.30 | 8 | 0.02 |

| 3 | 45.2 | 18.8 | 8.7 | 5.8 | 20 | 0.31 | 20 | 0.14 | 0 | n/a | 0 | n/a |

| 4 | 41.5 | 11.8 | 8.5 | 1.5 | 7 | 0.23 | 7 | 0.07 | 0 | n/a | 0 | n/a |

| 5 | 39.8 | 10.8 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 13 | 0.22 | 13 | 0.07 | 0 | n/a | 0 | n/a |

| 6 | 28.0 | 9.2 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 10 | 0.18 | 10 | 0.06 | 0 | n/a | 0 | n/a |

| 7 | 76.7 | 28.8 | 24.8 | 4.0 | 16 | 0.98 | 16 | 0.32 | 2 | 0.58 | 2 | 0.08 |

| 8 | 79.1 | 34.1 | 22.8 | 5.4 | 20 | 0.84 | 20 | 0.37 | 5 | 0.41 | 5 | 0.07 |

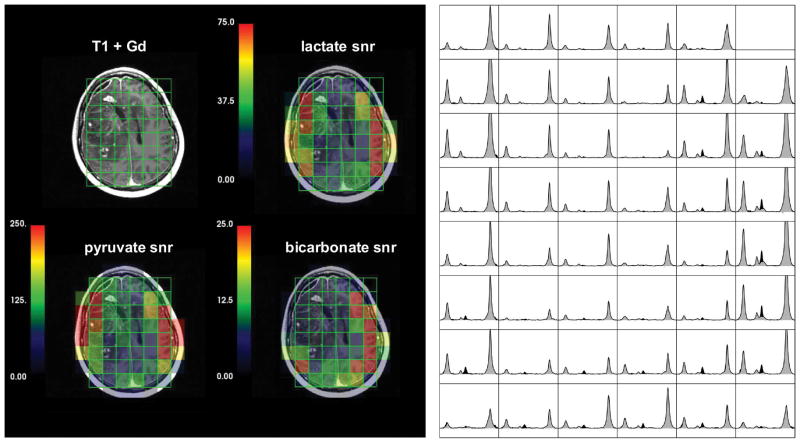

Figure 6 shows a T1 post-Gd image, maps of pyruvate, lactate and bicarbonate SNR and spectral arrays that were summed over all time points for patient 2. The low signal in the center of the brain is due to both the coil reception profile and the lower tissue content on voxels overlapping with the ventricles.

Figure 6.

A post-gadolinium T1-weighted image, color maps of integrated pyruvate, lactate and bicarbonate SNR and arrays of summed spectra from patients 2. The spectra with peaks shaded in gray are from the data reconstructed at the acquired reference frequency and the peaks shaded in black represent the data reconstructed at the bicarbonate frequency. The lactate and pyruvate peak intensities were determined from the former gray spectra and the bicarbonate peak intensities from the black spectra. The proposed coil setup with the clamshell transmit and the 8-channel bilateral receive arrays allowed the acquisition of 13C signals across the majority of the brain but with significantly lower SNR in central regions. The low SNR in the center of the brain was accentuated by reduced signal in the ventricles.

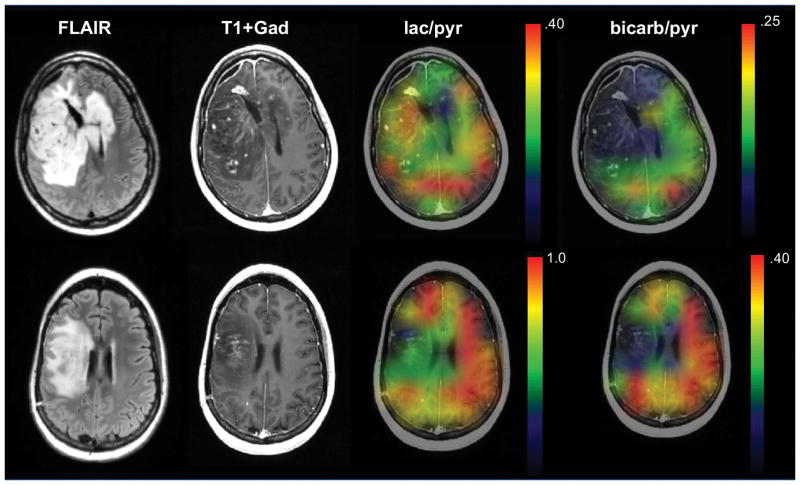

Figure 7 illustrates representative data from patient 2 and patient 8, showing anatomical images as well as color overlays of lactate/pyruvate and bicarbonate/pyruvate on the post-Gd T1-weighted anatomic images. Despite the differences in acquisition parameters and ratio values, both datasets showed substantial conversion of pyruvate to lactate in NAB and a lack of bicarbonate in the T2 lesion. Patient 2 had lactate/pyruvate in the T2 lesion with mean value of 0.30 compared with 0.38 in their NAB, while Patient 8 had mean lactate/pyruvate of 0.41 within the T2 lesion compared with 0.84 in their NAB.

Figure 7.

Anatomic and interpolated hyperpolarized 13C metabolite ratio image overlays estimated from 2D EPSI dynamic data acquired at 2 cm in plane resolution and 2 cm slice thickness from 2 patients with treated GBM. The differences in scales for the color overlay images are due to the single-band constant flip angle excitation scheme employed for patient 2 and the multi-band variable flip angle excitation scheme used for patient 8. Note that in both cases the bicarbonate/pyruvate was higher in regions of normal appearing brain. The patient in the upper images (patient 2) had progressive tumor at the time of this exam and the patient in the lower images (patient 8) was not characterizing as progressing until subsequent follow-up scans. lac/pyr and bicarb/pyr represent lactate/pyruvate and bicarbonate/pyruvate, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the safety and feasibility of using hyperpolarized 13C metabolic imaging for measuring real-time metabolism in the human brain utilizing pyruvate that is transported across the blood brain barrier via monocarboxylic transporter MCT1 (27). The slice-localized and 2D EPSI pulse sequences and 13C coils were first tested in a head shaped phantom. The spatial variation in signal intensity that was observed in the phantom data demonstrated the anticipated variation due to the reception profile of the two 4-channel paddle array coils, with a 3–4 fold reduction in intensity in the center of the phantom versus voxels within 2–4 cm of the lateral edges. The focus of these first patient studies was to determine the safety and feasibility. Another focus of the initial study was to define the time course of delivery and metabolism of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate in both the anatomic lesion and normal appearing brain, as opposed to seeking information about potential diagnostic capabilities at this early stage.

The SPINlab polarizer and the associated QC system provided pyruvate solution with an appropriate pH, temperature, EPA concentration and polarization level. The average polarization was of 37% which was approximately 2-fold higher than prior polarizations achieved using pre-clinical polarizers (12). This can be explained by the low sample vial temperature in the SPINLab (approximately 0.8 K) compared to the pre-clinical system (approximately 1.35 K) (28) and its higher magnetic field (5 T as opposed to 3.35 T). Although the dissolution and ensuing QC procedure, which lasted approximately 37s, extended the time from the start of dissolution to the scan (mean time of 88s) compared to the pre-clinical system (typically 10–15s), the high polarization levels generated from the SpinLab system were important for providing 13C data from human brain with high SNR. For patient 3, the pH was measured manually by the pharmacist, which extended the time from dissolution to data acquisition to 114s and resulted in the maximum SNR of pyruvate and lactate being lower compared to other data.

The coil setup with the clamshell transmit and the 8-channel bilateral receive arrays allowed the acquisition of 13C signals across the majority of the brain but with significantly lower SNR in central regions. This was expected based upon knowledge of the reception profile of the paddle coils and results from the phantom experiments, but was accentuated by the reduced signal in voxels overlapping the ventricles. Care must be taken when using this experimental set-up to avoid the misinterpretation of the variation in the levels of metabolite signals from different parts of the brain. When the SNR is adequate, the use of metabolite ratios provides a more meaningful within subject comparison. One approach to correct for this is to integrate all of the metabolic signals on a voxel by voxel basis for each coil and to use these as estimates of the coil sensitivity maps. Although this provides a simple approach that does not rely upon external standards, it may overestimate parameters in regions with high contributions from the vasculature or when metabolite T1s are very different. Other methods include the use of coil reception profiles that are estimated from numerical simulations or maps obtained from phantom studies (29), as well as the development of 13C volume or multi-channel head coils that provide more homogenous reception profiles.

The time course of signals from the slice-localized and 2D EPSI 13C data showed a similar pattern, with the maximum lactate appearing between 6s and 9s after the maximum pyruvate for all patients. Although there may be differences in the arrival time of the pyruvate based upon heart rate and local vasculature, the values observed for the 2D EPSI data were within one time point of the mean value and were similar to findings from our previously reported studies in non-human primates (21). Note that the flip angle excitation scheme employed for patients 2 to 6 was the simplest possible (uniform across the spectrum and constant of 10 degrees for each excitation) and the number of phase encodes was similar (10 for patients 2–5, 7 and 8 and 12 for patient 6). While this does provide a clear picture of the dynamic processes associated with delivery and metabolism of pyruvate within the brain, it uses more of the available magnetization during the early time points than the multi-band, variable flip angle scheme used for patients 7 and 8, which began with flip angles of 1.2 degrees for pyruvate and 8.7 degrees for lactate (22, 23). The higher SNR and ratio values that were obtained for lactate and bicarbonate using the more complex acquisition scheme indicates that it should be considered for future studies that require improved spatial resolution and increased coverage. The incorporation of compressed sensing reconstruction (2, 30, 31) and frequency specific echo planar imaging (19) are also likely to be important for obtaining 3D 13C metabolic imaging data from the brain.

The bicarbonate signals observed in the patient studies suggests that hyperpolarized 13C pyruvate may be useful for probing mitochondrial metabolism. Although the SNR of bicarbonate peaks was relatively small compared to pyruvate and lactate, it was detected in normal appearing brain for 7 out of 8 subjects. Of particular interest is that it was clearly present in voxels from contralateral brain but absent in voxels from the T2 lesion for patients 2, 7 and 8, whose scans showed sufficiently high enough SNR and had large enough lesions to provide definitive results. This differential is of interest for future studies and needs to be considered in pulse sequence design. The relatively low metabolite signals in voxels overlapping with the T2 lesion from patients 3–6 are consistent with them either being in regions with low reception profile or corresponding mainly to treatment effects rather than residual or recurrent tumor. None of these voxels were enhancing on corresponding post-Gd T1-weighted images or were in portions of the lesion that were found to progress in subsequent scans. Although the relatively high conversion of pyruvate to lactate in normal appearing brain meant that there was not a clear differential for voxels in the T2 lesion and surrounding brain for patient 2, who was the only subject with clinical status defined as progressive tumor and had high enough lactate SNR in tumor, it does suggest that this technique may be of interest for studying changes in metabolism associated with other neurological diseases.

The purpose of this paper was to report upon initial patient studies and to introduce the experimental setup that was designed for the acquisition of 13C data from human brain. While a relatively small group of patients were included, the time course of changes in metabolite levels and the appearance of lactate and bicarbonate in normal appearing brain were consistent between subjects and provide a basis for designing future, more advanced data acquisition schemes and experimental setups. The observation of substantial conversion of pyruvate to lactate in normal brain is in contrast to our prior results in studies from normal rats and non-human primates (2, 12, 21), where the conversion of pyruvate to lactate was relatively low. In our previous rodent studies that used similar experimental conditions the bicarbonate signal was not detected (12, 13), however, there have been several other reports in rats that have demonstrated the detection of bicarbonate in normal brain as well as in glioma (32–34). Whether this was due to differences in brain metabolism between humans and other species or because of the anesthesia (35) is unclear. Of interest for evaluating patients with brain tumors is that no bicarbonate was detected in lesions corresponding to recurrent tumor but that the ratios of lactate/pyruvate in T2 lesion were similar to or lower than the lactate/pyruvate in normal appearing brain. Further technical studies are required to optimize data acquisition parameters for the brain to provide 3D coverage and finer spatial resolution. This will be important for using hyperpolarized 13C agents to characterize metabolism in normal grey and white matter, as well as detecting changes associated with brain tumors and other types of pathology.

CONCLUSIONS

Experimental strategies for implementing hyperpolarized 13C metabolic imaging in human brain have been developed and initial patient studies have confirmed the safety and feasibility of using this technology. The results obtained indicate that the hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate was transported across the blood brain barrier and was converted to metabolic products, [1-13C]lactate and 13C-bicarbonate, in a time frame that can be measured using the pulse sequences and RF coils designed for this study. While additional optimization is required, these initial findings support further investigation of the technology in patients with brain tumors and other neurological diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Figure S1. Variable flip angle scheme for pyruvate and lactate. The flip angles for bicarbonate were the same as for lactate.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Jennifer Chow, Romelyn Delos Santos, Adam Autry, Kimberly Okamoto RN and Mary Mcpolin RT for assisting in patient scans. The first author was supported by a NCI training grant in translational brain tumor research (T32 CA151022), Kure It Grant for Underfunded Cancer Research, Discovery Grant from American Brain Tumor Association, and the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grant funded by Ministry of Science and ICT (No.2017R1C1B5018396). The support for the research studies came from NIH grants P41EB013598, R21CA170148 and P01CA118816.

References

- 1.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, et al. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(18):10158–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park I, Hu S, Bok R, Ozawa T, Ito M, Mukherjee J, et al. Evaluation of heterogeneous metabolic profile in an orthotopic human glioblastoma xenograft model using compressed sensing hyperpolarized 3D 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2013;70(1):33–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brindle K. New approaches for imaging tumour responses to treatment. Nature reviews Cancer. 2008;8(2):94–107. doi: 10.1038/nrc2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science (New York, NY) 1956;123(3191):309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albers MJ, Bok R, Chen AP, Cunningham CH, Zierhut ML, Zhang VY, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C lactate, pyruvate, and alanine: noninvasive biomarkers for prostate cancer detection and grading. Cancer research. 2008;68(20):8607–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeVience SJ, Lu X, Proctor J, Rangghran P, Melhem ER, Gullapalli R, et al. Metabolic imaging of energy metabolism in traumatic brain injury using hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):1907. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01736-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golman K, Petersson JS, Magnusson P, Johansson E, Akeson P, Chai CM, et al. Cardiac metabolism measured noninvasively by hyperpolarized 13C MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2008;59(5):1005–13. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guglielmetti C, Najac C, Didonna A, Van der Linden A, Ronen SM, Chaumeil MM. Hyperpolarized (13)C MR metabolic imaging can detect neuroinflammation in vivo in a multiple sclerosis murine model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114(33):E6982–e91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613345114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu S, Balakrishnan A, Bok RA, Anderton B, Larson PE, Nelson SJ, et al. 13C-pyruvate imaging reveals alterations in glycolysis that precede c-Myc-induced tumor formation and regression. Cell metabolism. 2011;14(1):131–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Brindle K, Chekmenev EY, Comment A, Cunningham CH, et al. Analysis of cancer metabolism by imaging hyperpolarized nuclei: prospects for translation to clinical research. Neoplasia (New York, NY) 2011;13(2):81–97. doi: 10.1593/neo.101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mignion L, Dutta P, Martinez GV, Foroutan P, Gillies RJ, Jordan BF. Monitoring chemotherapeutic response by hyperpolarized 13C-fumarate MRS and diffusion MRI. Cancer research. 2014;74(3):686–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park I, Larson PE, Zierhut ML, Hu S, Bok R, Ozawa T, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance metabolic imaging: application to brain tumors. Neuro-oncology. 2010;12(2):133–44. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park I, Mukherjee J, Ito M, Chaumeil MM, Jalbert LE, Gaensler K, et al. Changes in pyruvate metabolism detected by magnetic resonance imaging are linked to DNA damage and serve as a sensor of temozolomide response in glioblastoma cells. Cancer research. 2014;74(23):7115–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson SJ, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Larson PE, Harzstark AL, Ferrone M, et al. Metabolic imaging of patients with prostate cancer using hyperpolarized [1-(1)(3)C]pyruvate. Science translational medicine. 2013;5(198):198ra08. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham CH, Lau JY, Chen AP, Geraghty BJ, Perks WJ, Roifman I, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C Metabolic MRI of the Human Heart: Initial Experience. Circulation research. 2016;119(11):1177–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tropp J, Lupo JM, Chen A, Calderon P, McCune D, Grafendorfer T, et al. Multi-channel metabolic imaging, with SENSE reconstruction, of hyperpolarized [1-(13)C] pyruvate in a live rat at 3.0 tesla on a clinical MR scanner. Journal of magnetic resonance (San Diego, Calif : 1997) 2011;208(1):171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohliger MA, Larson PE, Bok RA, Shin P, Hu S, Tropp J, et al. Combined parallel and partial fourier MR reconstruction for accelerated 8-channel hyperpolarized carbon-13 in vivo magnetic resonance Spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;38(3):701–13. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stollberger R, Wach P. Imaging of the active B1 field in vivo. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1996;35(2):246–51. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon JW, Vigneron DB, Larson PE. Development of a symmetric echo planar imaging framework for clinical translation of rapid dynamic hyperpolarized 13 C imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2017;77(2):826–32. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larson PE, Bok R, Kerr AB, Lustig M, Hu S, Chen AP, et al. Investigation of tumor hyperpolarized [1-13C]-pyruvate dynamics using time-resolved multiband RF excitation echo-planar MRSI. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2010;63(3):582–91. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park I, Larson PE, Tropp JL, Carvajal L, Reed G, Bok R, et al. Dynamic hyperpolarized carbon-13 MR metabolic imaging of nonhuman primate brain. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2014;71(1):19–25. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson PE, Hu S, Lustig M, Kerr AB, Nelson SJ, Kurhanewicz J, et al. Fast dynamic 3D MR spectroscopic imaging with compressed sensing and multiband excitation pulses for hyperpolarized 13C studies. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2011;65(3):610–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xing Y, Reed GD, Pauly JM, Kerr AB, Larson PE. Optimal variable flip angle schemes for dynamic acquisition of exchanging hyperpolarized substrates. Journal of magnetic resonance (San Diego, Calif : 1997) 2013;234:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crane JC, Olson MP, Nelson SJ. SIVIC: Open-Source, Standards-Based Software for DICOM MR Spectroscopy Workflows. International journal of biomedical imaging. 2013;2013:169526. doi: 10.1155/2013/169526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson SJ. Analysis of volume MRI and MR spectroscopic imaging data for the evaluation of patients with brain tumors. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2001;46(2):228–39. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stollberger R, Wach P. Imaging of the active B1 field in vivo. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 1996;35(2):246–51. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halestrap AP. Monocarboxylic acid transport. Comprehensive Physiology. 2013;3(4):1611–43. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Leach AM, Clarke N, Urbahn J, Anderson D, Skloss TW. Dynamic nuclear polarization polarizer for sterile use intent. NMR in biomedicine. 2011;24(8):927–32. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dominguez-Viqueira W, Geraghty BJ, Lau JY, Robb FJ, Chen AP, Cunningham CH. Intensity correction for multichannel hyperpolarized 13C imaging of the heart. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2016;75(2):859–65. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu S, Lustig M, Balakrishnan A, Larson PE, Bok R, Kurhanewicz J, et al. 3D compressed sensing for highly accelerated hyperpolarized (13)C MRSI with in vivo applications to transgenic mouse models of cancer. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2010;63(2):312–21. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu S, Lustig M, Chen AP, Crane J, Kerr A, Kelley DA, et al. Compressed sensing for resolution enhancement of hyperpolarized 13C flyback 3D-MRSI. Journal of magnetic resonance (San Diego, Calif : 1997) 2008;192(2):258–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butt SA, Sogaard LV, Magnusson PO, Lauritzen MH, Laustsen C, Akeson P, et al. Imaging cerebral 2-ketoisocaproate metabolism with hyperpolarized (13)C magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2012;32(8):1508–14. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park JM, Recht LD, Josan S, Merchant M, Jang T, Yen YF, et al. Metabolic response of glioma to dichloroacetate measured in vivo by hyperpolarized (13)C magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Neuro-oncology. 2013;15(4):433–41. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JM, Spielman DM, Josan S, Jang T, Merchant M, Hurd RE, et al. Hyperpolarized (13)C-lactate to (13)C-bicarbonate ratio as a biomarker for monitoring the acute response of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment. NMR in biomedicine. 2016;29(5):650–9. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Josan S, Hurd R, Billingsley K, Senadheera L, Park JM, Yen YF, et al. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on hyperpolarized (13)C metabolic measurements in rat brain. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2013;70(4):1117–24. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Figure S1. Variable flip angle scheme for pyruvate and lactate. The flip angles for bicarbonate were the same as for lactate.