Abstract

Background

Maternal mortality is a sentinel indicator of health care quality. Our purpose was to analyze trends in Texas maternal mortality by demographic characteristics and cause of death, and to evaluate data quality.

Methods

Maternal mortality data were initially analyzed by single years, but then were grouped into 5-year averages (2006–2010 and 2011–2015) for more detailed analyses. Rates were computed per 100 000 live births. A two-proportion z test or Poisson regression for numerators <30 was used to evaluate differences.

Results

The Texas maternal mortality rate increased from 18.6 in 2010 to 38.7 in 2012, and then declined nonsignificantly to 32.5 in 2015. The 2011–2015 rate (34.2) was 87% higher than the 2006–2010 rate (18.3). In 2011–2015, the maternal mortality rate for women ≥40 years (558.8) was 27 times higher than for women <40 years (20.7). From 2006–2010 to 2011–2015, the maternal mortality rate increased by 121% for women ≥40 years and by 55% for women <40 years. The rate increased by 132% for nonspecific causes of death, and by 54% for specific causes. Rates for women <40 years for specific causes increased by 36%.

Conclusions

The observed increase in maternal mortality in Texas from 2006–2010 to 2011–2015 is likely a result of both a true increase in rates and increased overreporting of maternal deaths, as indicated by implausibly high and increasing rates for women aged ≥40 years and among nonspecific causes of death. Efforts are needed to strengthen reporting of death certificate data, and to improve access to quality maternal health care services.

Keywords: cause-of-death analysis, maternal death, race and ethnic disparities

1 INTRODUCTION

Maternal mortality is a sentinel indicator of health care quality.1–5 A recent study found a sharp increase in maternal mortality in Texas between 2010 and 2012.6 This increase drew national attention in part because the increase in maternal mortality roughly coincided with deep cuts in the provision of women’s health services in Texas.7,8 The previous study was based on death certificate data, which do not include access-to-care measures, so it was unable to examine the potential influence of the cuts.6 There have been subsequent discussions about the magnitude, timing, and causes of the increase; however, the fact that maternal mortality increased in Texas is not in dispute.9,10

To improve reporting of maternal deaths, a pregnancy question was added to the United States standard death certificate in 2003 to ascertain whether female decedents were pregnant or postpartum at the time of death. Texas added this question to its death certificate in 2006.6 In the United States, all death certificates of women identified by the pregnancy question as being pregnant at the time of death or within 42 days before death are coded as maternal deaths, except for deaths as a result of external causes of injury (ie, accidents, homicide, suicide).11,12 Recent studies have identified problems in reporting with the pregnancy question.13,14 A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report from maternal mortality review committees in four states found that 15% (97/650) of “maternal deaths” were misreported, predominantly because of errors in the pregnancy question, since the women involved were confirmed to be not pregnant or postpartum within 1 year of death.14

We undertook a more detailed examination of maternal mortality data from Texas to further understand the potential public health implications of trends in Texas maternal mortality over the past decade (2006–2015). We analyzed the increase by demographic characteristics and detailed causes of death: (1) to identify trends and at-risk populations to assist in targeting prevention efforts; and (2) to begin to evaluate data quality.

2 METHODS

The National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) is the source of official United States maternal mortality statistics used for subnational and international comparisons.15 Data used in this observational study are based on information reported on death certificates filed in state vital statistics offices, and subsequently compiled into national data.16 The national data are used in preference to data reported by the Texas Health Department because they are collected and coded in a uniform way, which facilitates comparisons with data from other states (see Results).16 These data are publicly available through the National Center for Health Statistics website, and through CDC-WONDER.17,18 Physicians, medical examiners, or coroners complete the medical portion of the death certificate, including the cause of death.16

Throughout this analysis, we used the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of maternal death as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.19 Late maternal deaths (shown as auxiliary information at the bottom of Table 2) are pregnancy-related deaths that occurred from 43 days to 1 year after the end of pregnancy.19

TABLE 2.

Maternal and late maternal deaths and mortality rates by cause of death, Texas, 2006–2010 and 2011–2015

| Underlying cause of death | 2006–2010 | 2011–2015 | Percent change 2006–2010 to 2011–2015 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Number of deaths |

Percent of total maternal deaths |

Ratea | Number of deaths |

Percent of total maternal deaths |

Ratea | ||

| Total maternal deaths (during pregnancy or within 42 d after the end of pregnancy) (A34, O00–O95, O98–O99) | 366 | 100.0 | 18.3 | 668 | 100.0 | 34.2 | 87.2*** |

|

| |||||||

| Total direct obstetric causes (A34, O00–O92) | 227 | 62.0 | 11.3 | 425 | 63.6 | 21.8 | 92.0*** |

|

| |||||||

| Pregnancy with abortive outcome (includes ectopic pregnancy) (O00–O07)b | 10 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 12 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 23.1 |

|

| |||||||

| Hypertensive disorders (O10–O16)b | 42 | 11.5 | 2.1 | 51 | 7.6 | 2.6 | 24.5 |

|

| |||||||

| Obstetric hemorrhage (O20, O43.2, O44–O46, O67, O71.0–O71.1, O71.3–O71.4, O71.7, O72) | 20 | 5.5 | 1.0 | 23 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 20.0 |

|

| |||||||

| Pregnancy-related infection (O23, O41.1, O75.3, O85, O86, O91)b | - | - | - | 11 | 1.6 | 0.6 | - |

|

| |||||||

| Other obstetric complications (O21–O22, O24–O41.0, O41.8–O43.1, O43.8–O43.9, O47–O66, O68–O70, O71.2, O71.5, O71.6, O71.8, O71.9, O73–O75.2, O75.4–O75.9, O87–O90, O92)b | 146 | 39.9 | 7.3 | 329 | 49.3 | 16.9 | 132.0*** |

|

| |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus in pregnancy (O24) | - | - | - | 20 | 3.0 | 1.0 | - |

|

| |||||||

| Liver disorders in pregnancy (O26.6) | 15 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 33 | 4.9 | 1.7 | 125.6** |

|

| |||||||

| Other specified pregnancy-related conditions (O26.8) | 77 | 21.0 | 3.8 | 203 | 30.4 | 10.4 | 170.4*** |

|

| |||||||

| Obstetric embolism (O88) | 23 | 6.3 | 1.1 | 22 | 3.3 | 1.1 | −1.9 |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiomyopathy in the puerperium (O90.3) | - | - | - | 22 | 3.3 | 1.1 | - |

|

| |||||||

| Total indirect causes (O98–O99)b | 114 | 31.1 | 5.7 | 216 | 32.3 | 11.1 | 94.3*** |

|

| |||||||

| Diseases of the circulatory system (O99.4) | 37 | 10.1 | 1.8 | 46 | 6.9 | 2.4 | 27.5 |

|

| |||||||

| Diseases of the respiratory system (O99.5) | 11 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 10 | 1.5 | 0.5 | −6.8 |

|

| |||||||

| Other specified diseases and conditions (O99.8) | 54 | 14.8 | 2.7 | 123 | 18.4 | 6.3 | 133.6*** |

|

| |||||||

| Obstetric death of unspecified cause (O95) | 25 | 6.8 | 1.2 | 27 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 10.8 |

|

| |||||||

| Late maternal causes (43 d-1 y after the end of pregnancy) (O96–O97) | 128 | - | 6.4 | 94 | - | 4.8 | −24.7* |

P < .05;

P < .01,

P < .001.

Rate per 100 000 live births. Denominators were 2 000 877 births in 2006–2010 and 1 950 896 births in 2011–2015.

Individual cause-of-death categories are shown separately under subtotals when they contained ≥10 deaths in either time period; however, residual categories are not shown to save space and promote clarity of presentation. Data not shown separately for categories with <10 deaths during the period.

ICD-10 mortality codes were used throughout this paper to classify causes of maternal death.19 From 1999 to the present, mortality data in the United States have been coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10).19 Maternal deaths are denoted by codes A34, O00-O95, O98-O99 (see Table 2 for specific code titles), whereas late maternal deaths are denoted by codes O96-O97.15,19 Maternal deaths are further subdivided into direct and indirect obstetric deaths.19 Direct obstetric deaths are deaths resulting from obstetric complications of pregnancy, labor and the puerperium, from interventions, omissions, incorrect treatment, or from a chain of events resulting from any of the above (ICD-10 codes A34, O00-O92).19 Indirect obstetric deaths are deaths resulting from previous existing disease or disease that developed during pregnancy, and were not the result of direct obstetric causes, but that were aggravated by the physiological effects of pregnancy (O98-O99).19 Deaths of unknown cause (O95) are not classified as either direct or indirect causes.

2.1 Data analysis

We examined the single-year trend of maternal mortality rates for Texas from 2006 to 2015, using Poisson regression with linear spline terms to examine the change in slopes. However, small annual numbers of deaths made more detailed analysis of single-year trends impracticable. Therefore, we grouped the data into two 5-year age groups: 2006–2010 (before the rapid increase in maternal deaths) and 2011–2015 (during/after the increase) to provide sufficient numbers of cases for statistically reliable analysis by characteristics. We analyzed data by maternal age (by 5-year age groups, and for women <40 and ≥40 years of age); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic); and for detailed causes of death.

To evaluate data quality, we looked for patterns in the data that were markedly different from those found in other reliable maternal mortality data sources, such as the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Mortality in Great Britain, or CDC’s Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System.20,21 We also analyzed trends for a grouping of nonspecific causes of death, including other specified pregnancy-related conditions (O26.8), unknown cause (O95), and other specified diseases and conditions complicating pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium (O99.8).13,22 These nonspecific categories are where deaths that do not easily fit into the ICD maternal mortality coding rubric are classified.17,18 No further information is provided as to the specific causes of death for these cases.17,18 To put the Texas results into a broader context, we also compared results for 2011–2015 with another recent study of maternal mortality from 27 states and Washington, DC, in 2013–2014.13 Maternal mortality rates were computed per 100 000 live births. A two-proportion z test or Poisson regression for numerators <30 was used to test differences in rates for statistical significance.23

Finally, since recent studies found evidence of possible overreporting of maternal deaths with the pregnancy question,13,14 we did a sensitivity analysis to assess the potential influence of a 0.5%, 1%, and 1.5% level of overreporting of pregnancy status with the pregnancy question. We computed the number of female nonmaternal deaths from natural causes (excluding accidents, homicide, and suicide) by 5-year age groups, and estimated how different levels of incorrect reporting of these deaths as maternal deaths would affect maternal mortality rates by age. Because the study was based on de-identified, aggregated data from United States government public-use data sets, it was exempt from requiring institutional review board approval.

3 RESULTS

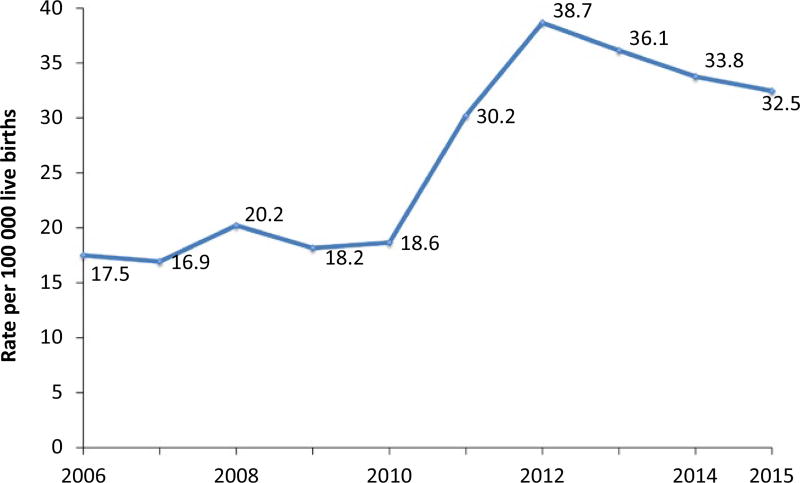

The Texas maternal mortality rate was 17.5 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births in 2006, the first year that the new pregnancy question was in use on the state death certificate. The slope from 2006 to 2010 did not show a significant increase in the maternal mortality rate (RR 1.03 [95% CI 0.96–1.11], P = .37) (Figure 1). However, after 2010, the maternal mortality rate increased sharply to 30.2 in 2011 and to a peak of 38.7 in 2012 (RR [2010–2012] 1.41, P < .001). After 2012, the rate showed a downward, but nonsignificant, trend to 32.5 in 2015 (RR [2012–2015] 0.93, P = .061). When 5-year averages were compared, the maternal mortality rate of 34.2 for the 2011–2015 period was 87% higher than the rate of 18.3 for 2006–2010 (P < .001).

FIGURE 1.

Maternal mortality rates, Texas, 2006–2015

3.1 Demographic characteristics

When examined by race and ethnicity, the maternal mortality rate nearly doubled (96% increase) for non-Hispanic white women, from 19.4 in 2006–2010 to 38.0 in 2011–2015 (P < .001) (Table 1). The rate also doubled (106% increase) for non-Hispanic black women from 41.6 in 2006–2010 to 85.6 in 2011–2015 (P < .001). In both 2006–2010 and 2011–2015, the maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic black women was more than twice the rate for non-Hispanic white women (P < .001). Rates for Hispanic women increased by 62% during the period (P < .001). In 2011–2015, the maternal mortality rate for Hispanic women (20.5) was 46% lower than the rate for non-Hispanic white women (38.0) (P < .001).

TABLE 1.

Maternal deaths and mortality rates by race/ethnicity and maternal age, Texas 2006–2010 and 2011–2015

| Race/ethnicity and maternal age |

2006–2010 | 2011–2015 | Percent change 2006–2010 to 2011–2015 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Maternal deaths |

Births | Ratea | Maternal deaths |

Births | Ratea | ||

| Total | 366 | 2 000 877 | 18.3 | 668 | 1 950 896 | 34.2 | 87.2*** |

|

| |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 134 | 692 018 | 19.4 | 261 | 687 620 | 38.0 | 96.0*** |

|

| |||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 95 | 228 375 | 41.6 | 198 | 231 212 | 85.6 | 105.9*** |

|

| |||||||

| Hispanic | 126 | 996 097 | 12.6 | 191 | 931 570 | 20.5 | 62.1*** |

|

| |||||||

| Maternal age (y) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| <40 | 261 | 1 959 339 | 13.3 | 393 | 1 901 681 | 20.7 | 55.1*** |

|

| |||||||

| <20 | 16 | 266 242 | 6.0 | 26 | 191 058 | 13.6 | 126.4* |

|

| |||||||

| 20–24 | 52 | 544 885 | 9.5 | 55 | 490 630 | 11.2 | 17.5 |

|

| |||||||

| 25–29 | 67 | 546 120 | 12.3 | 86 | 548 916 | 15.7 | 27.7 |

|

| |||||||

| 30–34 | 63 | 407 679 | 15.5 | 117 | 460 622 | 25.4 | 64.4*** |

|

| |||||||

| 35–39 | 63 | 194 413 | 32.4 | 109 | 210 455 | 51.8 | 59.8** |

|

| |||||||

| ≥40 | 105 | 41 538 | 252.8 | 275 | 49 215 | 558.8 | 121.1*** |

Rate per 100 000 live births in specified group.

P < .05;

P < .01,

P < .001.

From 2006–2010 to 2011–2015, maternal mortality rates increased for all age groups, although the increases were not statistically significant for women in their twenties (Table 1). Rates increased by 60%–64% for women in their thirties (P < .001). For women aged ≥40 years, the maternal mortality rate more than doubled (121% increase) from 2006–2010 to 2011–2015 (P < .001).

Women aged ≥40 years had the highest maternal mortality rates among the various age groups. In 2006–2010, the maternal mortality rate for women ≥40 years (252.8) was 19 times the rate for women <40 years (13.3). In 2011–2015, the maternal mortality rate for women ≥40 years (558.8) was 27 times the rate for women <40 years (20.7). The increase for the ≥40 age group accounted for 56% of the overall increase in maternal deaths between the two time periods. In 2011–2015, 41% of total maternal deaths were to women aged ≥40 years, compared with just 3% of live births (Table 1). The pattern of much higher maternal mortality rates for women aged ≥40 years held when examined by race and ethnicity (tabular data not shown).

3.2 Cause of death

From 2006–2010 to 2011–2015, maternal mortality rates increased by 92% for direct obstetric causes (P < .001) and by 94% for indirect obstetric causes (P < .001) (Table 2). Direct obstetric causes accounted for nearly two-thirds (64%) and indirect causes one-third (32%) of maternal deaths in 2011–2015. There was little change in the small number of deaths (4% in 2011–2015) classified to cause unknown (ICD-10 code P95). When the specific subcategories of direct obstetric deaths were examined, the only significant increases were for liver disorders in pregnancy (O26.6), which increased from a rate of 0.7 per 100 000 births in 2006–2010 to 1.7 in 2011–2015 (P < .01), and for “Other” specified pregnancy-related conditions (O26.8), which increased from a rate of 3.8 to 10.4 (P < .001). The increase of 126 maternal deaths in the nonspecific O26.8 category accounted for almost two-thirds of the overall increase in direct obstetric deaths (198) during the period.

When the subcategories of indirect obstetric causes were examined, only the “Other specified diseases and conditions” (O99.8) category showed a statistically significant increase from 2006–2010 to 2011–2015. Rates for this category more than doubled (134% increase) from 2.7 in 2006–2010 to 6.3 in 2011–2015. The increase of 69 maternal deaths for this nonspecific category accounted for more than two-thirds of the overall increase in indirect obstetric deaths (n = 102) between the two time periods.

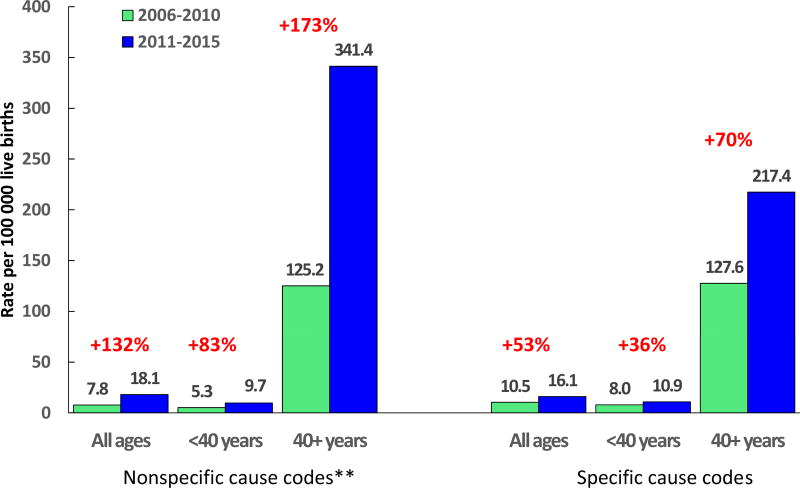

3.3 Assessing the influence of nonspecific causes on maternal mortality trends

Maternal mortality rates for all nonspecific causes combined increased by 132%, from 7.8 in 2006–2010 to 18.1 in 2011–2015 (P < .001) (Figure 2). This increase was much larger than the 54% increase for all other causes combined. There was an overall increase of 302 maternal deaths across the two time periods, and the nonspecific “other” causes accounted for 197 (65%) of them. In 2011–2015, maternal mortality rates from nonspecific causes were 35 times higher for women aged ≥40 years than for women <40 years, whereas among specific causes, rates were 20 times higher. For women aged ≥40 years, 61% of all maternal deaths were because of nonspecific causes in 2011–2015, compared with 47% for women <40 years.

FIGURE 2.

Maternal mortality rates by age for specific and nonspecific causes of death, Texas, 2006–2010 and 2011–2015. **Nonspecific cause of death codes are 026.8, 095, 099.8. Specific codes are all others combined. Statistically significant increases shown above bars

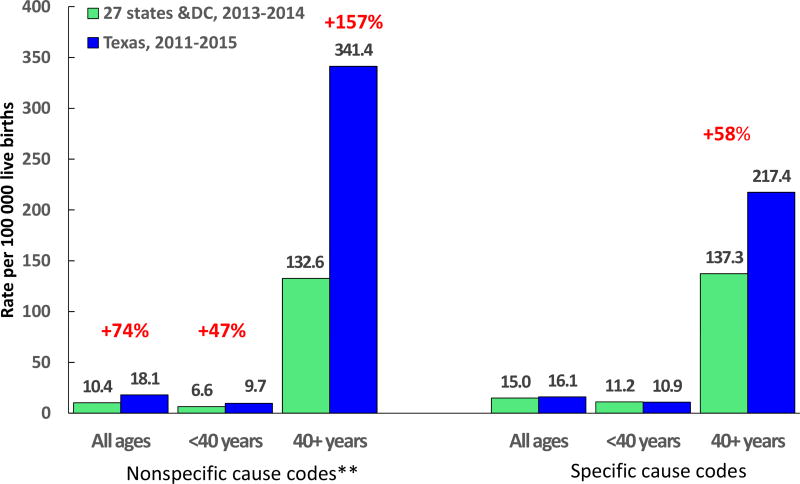

3.4 Comparing Texas data with other state populations

We compared 2011–2015 Texas data with 2013–2014 data from 27 states and the District of Columbia from a recently published study11 (Figure 3). Compared with data from the 27 states and the District of Columbia, Texas maternal mortality rates were 74% higher for nonspecific causes: 47% higher for women aged <40 years and 157% higher for women ≥40 years. However, for specific cause codes, maternal mortality rates in Texas were not significantly different for all ages combined or for women aged <40 years. For women aged ≥40 years, Texas rates were 61% higher among specific cause codes.

FIGURE 3.

Maternal mortality rates by age for specific and nonspecific causes of death, Texas 2011–2015 and 27 states and Washington, DC 2013–2014. **Nonspecific cause of death codes are 026.8, 095, 099.8. Specific codes are all others combined. Statistically significant increases shown above bars

3.5 Sensitivity analysis

Finally, given the pronounced differences in reported maternal deaths by age and preponderance of nonspecific causes, we did a sensitivity analysis to model the effect on maternal mortality rates of a possible 0.5%, 1.0%, and 1.5% overreporting of pregnancy/postpartum status with the pregnancy question (Table 3). We found that a 1% overreporting of pregnancy/postpartum status increased reported maternal mortality rates by 14%–18% for women in their teens to early thirties, and by 30% for women aged 35–39 years. In contrast, the maternal mortality rate for women aged 40–54 years more than doubled (105% increase) with 1% overreporting of maternal deaths.

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity analysis of possible influence of 0.5%, 1%, and 1.5% overreporting of the pregnancy checkbox on maternal mortality rates, Texas, 2011–2015

| Age (y) | Number of maternal deaths |

Number of female deaths from natural causes (excludes maternal deaths) |

Number of maternal deaths with 0.5% false positives added to total |

Percent increase in MMR with 0.5% false positive rate |

Number of maternal deaths with 1% false positives added to total |

Percent increase in MMR with 1% false positive rate |

Number of maternal deaths with 1.5% false positives added to total |

Percent increase in MMR with 1.5% false positive rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 668 | 36 612 | 851 | 27.4 | 1034 | 54.8 | 1217 | 82.2 |

| <40 | 393 | 7792 | 432 | 9.9 | 471 | 19.8 | 510 | 29.7 |

| 15–19 | 26 | 452 | 28 | 8.7 | 31 | 17.4 | 33 | 26.1 |

| 20–24 | 55 | 786 | 59 | 7.1 | 63 | 14.3 | 67 | 21.4 |

| 25–29 | 86 | 1232 | 92 | 7.2 | 98 | 14.3 | 104 | 21.5 |

| 30–34 | 117 | 2099 | 127 | 9.0 | 138 | 17.9 | 148 | 26.9 |

| 35–39 | 109 | 3223 | 125 | 14.8 | 141 | 29.6 | 157 | 44.4 |

| 40–54 | 275 | 28 820 | 419 | 52.4 | 563 | 104.8 | 707 | 157.2 |

MMR, maternal mortality rate.

4 DISCUSSION

The situation in Texas represents parallel public health emergencies, namely: (1) a sharp increase in the maternal mortality rate in recent years; and (2) a lack of reliable data to better characterize and further understand the increase. Despite measurement issues, there is still substantial evidence of a true increase in maternal mortality risk in Texas from 2006–2010 to 2011–2015. When we limited the analysis to cases with specific cause codes for women <40 years, who are less subject to misclassification errors, a significant increase (36%) still occurred in maternal mortality between the two time periods. This finding is in contrast to a recent study of data from 27 states and Washington, DC, which did not find an increase for these deaths.13 It is also in contrast to data from 157 of 183 countries that had decreases in maternal mortality from 2000 to 2013.2 The United Nations Millennium Development Goal to reduce maternal mortality led to unprecedented efforts to reduce maternal mortality worldwide.2,5,24 From 1990 to 2015, global maternal mortality declined by 44%, and by 48% among industrialized countries.24 The high maternal mortality rates in Texas, the 2010–2012 increase, and the large and persistent racial and ethnic disparities warrant concerted actions by clinicians and policy makers.

Improvements in clinical care are essential to lowering maternal mortality, and should include clinician training in how to quickly recognize and respond to obstetric emergencies.25 However, a focus beyond the moment of birth is also important.25 For example, preconception identification and treatment of chronic disease and behavioral health problems can enable women to begin pregnancy as healthy as possible.25 Likewise systems that cover women while pregnant, but then exclude them soon after delivery,26 ignore the fact that a significant proportion of maternal deaths occur after a woman has given birth.14 For example, in Texas, 2017 Medicaid eligibility limits for pregnant women (203% of the federal poverty level) were slightly above the national median, whereas eligibility limits for parents in a family of three (18% of the federal poverty level) were tied with Alabama for the most restrictive in the country.27

We also found substantial evidence of overreporting of maternal deaths, particularly for women aged ≥40 years and among nonspecific causes of death. United States coding rules state that unless the cause of death is an accident, suicide, or homicide, if the pregnancy or postpartum within 42 days checkbox is checked, the record is coded as a maternal death, regardless of what is written in the cause-of-death section.11,12 This method puts tremendous emphasis on the pregnancy question as almost the sole determinant of whether the death of a woman of reproductive age is coded as maternal or nonmaternal. However, until recently, little quality control has been done on this data item. A sensitivity analysis found that a 1% level of misclassification more than doubled the number of reported maternal deaths for women aged 40–54 years. This finding is because deaths are more common and pregnancies rarer among women aged 40–54 years than for younger women. The pattern of potential misclassification among older women was not limited to Texas, but may have been more pronounced there, as can be seen when comparing Texas with a 27-state analysis for 2013–2014.13 Although the 27 states and Washington, DC, also had an exceptionally high rate for nonspecific causes to women ≥40 years (135 per 100 000), the Texas rate for a comparable population was more than double the 27-state average (341 per 100 000) and was 36 times the rate for Texas women aged 25–29 years. By comparison, data from Great Britain, often touted as the gold standard for maternal mortality investigation, found rates for women aged ≥40 years to be 3–4 times those for women aged 25–29 years,21 and data from the U.S. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System found maternal mortality rates for women ≥40 years were 4–5 times those for women aged 25–29 years.20 A better understanding is needed of the greater risks for women ≥40 years,20,21,28 but this is confounded by misclassification problems. In contrast, the Texas maternal mortality rate for specific causes for women aged <40 years (10.9) was not different from the 27-state estimate (11.3) (Figure 3).

This paper has a limitation in that the analysis is based on data from the NVSS and not specific case reviews. The NVSS is the foundational data system for maternal mortality analysis, and is the data system on which other more detailed data systems such as the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System and maternal mortality reviews are largely based.14,20 It should be a reliable source for assessing cause of death, trends in overall rates, and rates for subgroups when there are sufficient number of cases. However, it is a national system built on state reporting, and the extraordinarily high rates among older mothers and for nonspecific causes call into question the reporting in Texas and other states.13 Texas has established a maternal mortality review committee to examine maternal deaths in more detail than is possible with national databases.29 Ideally, as part of that examination, a careful assessment of the quality of reporting, particularly for older women with nonspecific codes, could clarify some of the questions concerning ascertainment.

Quality improvement efforts need to focus on improving the accuracy of the information from the pregnancy question. Periodic validation studies and the implementation of data quality checks at both the state and national level are essential to improving reporting. State and Federal agencies should provide training to persons who complete death certificates to emphasize the importance of accurate reporting with the pregnancy question. A percentage of records, including 100% of records for women aged ≥40 years or coded to nonspecific causes, should be routinely queried back to the certifier to confirm the fact of pregnancy. In addition, changes to coding to decrease the near-exclusive reliance on the pregnancy question to identify maternal deaths might improve data quality. The recent growth in state maternal mortality review committees can improve data quality,30 and can help to identify both overreporting and underreporting of maternal deaths,31 but only if information from maternal mortality reviews is used to update vital statistics information on the cause and circumstances of death.

Both the increasing maternal mortality rates in Texas and the substantial data problems identified in this study constitute an urgent call for action. Reducing maternal mortality overall and particularly for non-Hispanic black women will require a greater focus on women’s health in the life course,3 with efforts needed at the national, state, and local levels to improve data quality, access to care, and quality of services.32

Acknowledgments

Funding information

Marian MacDorman’s work was partially supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041, Maryland Population Research Center.

References

- 1.Amnesty International. Deadly Delivery: The Maternal Health Care Crisis in the USA. Amnesty International Publications; London: 2010. [Accessed November 1, 2017]. http://www.amnestyusa.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/deadlydelivery.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013—Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassenbaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggershall MS, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:980–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt P, de Bueno Mesquita J. Reducing Maternal Mortality—The Contribution of the Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health. University of Essex Human Rights Centre. New York City, NY: United Nations Population Fund; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Burden of Disease. Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990– 2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2015;2016:1775–1812. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate—disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447–455. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson AJ, Flores-Vasquez IM, Allgeyer RL, Schenkkan P, Potter JE. Effect of removal of Planned Parenthood from the Texas Women’s Health Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;3:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1511902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krugman Paul. States of cruelty. [Accessed December 1, 2017];New York Times. 2016 Aug 29; https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/29/opinion/states-of-cruelty.html?_r=0c.

- 9.Baeva S, Archer NP, Ruggiero K, et al. Maternal mortality in Texas. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:614–620. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1595809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Texas Department of Health Services. 2012 Mortality. [Accessed January 17, 2017]; http://dshs.texas.gov/chs/vstat/vs12/nmortal.shtm.

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics, Instruction Manual Part 2a. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [Accessed November 16, 2016]. Instructions for Classifying the Underlying Cause of Death, ICD-10, 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/instruction_manuals.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics, Instruction Manual Part 2b. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [Accessed November 16, 2016]. Instructions for Classifying the Multiple Causes of Death, ICD-10, 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/instruction_manuals.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Thoma M. Trends in maternal mortality by socio-demographic characteristics and cause of death, 27 states and Washington DC, 2008–9 to 2013–14. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:811–818. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report from Maternal Mortality Review Committees: A View into Their Critical Role. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality and related concepts. Vital Health Stat 3. 2007;33:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths, Final data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2016;65:1–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics. Vital statistics data available online. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; [Accessed January 1, 2017]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/VitalStatsOnline.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed April 1, 2017];Detailed Mortality File 1999–2014 on CDC WONDER Online data base. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html.

- 19.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Accessed December 1, 2017]. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creanga A, Berg C, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce C, Callaghan B. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:5–12. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight M, Nair M, Tuffnell D, et al., editors. on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care— Surveillance of Maternal Deaths in the UK 2012–14 and Lessons Learned to Inform Maternity Care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–14. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creanga AA, Callaghan WM. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate—disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:206–207. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015—Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Patient Safety Bundles. [Accessed July 13, 2017];Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-program/

- 26.Daw MR, Swartz Hatfield LA, Sommer BD. Women in the United States experience high rates of coverage ‘churn’ in months before and after childbirth. Health Aff. 2017;36:598–606. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. [Accessed July 13, 2017]. http://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-adults-as-a-percent-of-the-federal-poverty-level/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph KS, Lisonkova S, Muraca GM, et al. Factors underlying the temporal increase in maternal mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:91–100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services. Joint Biennial Report. Texas Dept of State Health Services; Jul, 2016. [Accessed July 13, 2017]. https://www.dshs.texas.gov/mch/maternal_mortality_and_morbidity.shtm. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman D, Stampfel C, Creanga AA, et al. Revival of a core public health function: state-and urban-based maternal death review processes. J Womens Health. 2013;22:395–398. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell C, Lawton E, Morton C, McCain D, Holtby S, Main E. California pregnancy-associated mortality review: mixed methods approach for improved case identification, cause of death analyses and translation of findings. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:518–526. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chescheir NC. Drilling down on maternal mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:427–428. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]