Abstract

Although they experience high rates of chronic illness, low-income minority communities have traditionally underutilized palliative care services compared to whites and those with higher incomes. One reason for this trend is lack of screening by community providers. We utilized a community-based participatory research approach to develop and implement an innovative multidomain palliative care screening tool in aging service agencies. Participants were aging service providers and clients in the East and Central Harlem neighborhoods of New York City, which are characterized by high poverty, largely African American and Latino populations, disproportionally high rates of chronic conditions, and limited health-care access. Screening tool development included reviewing existing measures and obtaining feedback from an expert panel, aging service providers, and older adults. We developed a 22-item tool covering 3 domains of palliative care need (physical symptoms, emotional concerns, and goals of care), which can be administered in 10 to 15 minutes. Sixteen providers at 2 aging service agencies were trained to use the tool over a 3-month pilot period. The tool showed evidence of feasibility of implementation, with 44 older adult clients screened. Providers reported high acceptability, 36% of clients screened positive, and the majority accepted referrals to outpatient palliative care clinics. The screening tool has the potential to increase palliative care utilization among underserved community-dwelling older adults and may improve their quality of life, potentially in communities worldwide. Future work should examine the psychometric proprieties of the tool, examine predictors of positive screens, explore its impact on clinical outcomes, and expand its reach.

Keywords: palliative care, screening, assessment, measurement, underserved, community-based

Introduction

An estimated 80% of older adults have 1 chronic condition, and 50% have 2 or more.1 Chronic conditions are frequently accompanied by high symptom burden in later life, such as pain, mobility problems, fatigue, and depression, all of which are associated with unnecessary hospitalization and poor quality of life1–3 and increased emotional, social, and financial costs.1,2,4 Palliative care5 has been shown to decrease symptom burden,6 improve patient quality of life,7–10 and enhance patient and caregiver satisfaction with care11,12 in chronically ill older adults.

Racial and ethnic minority older adults in low-income communities may particularly benefit from palliative care, as they experience higher prevalence of chronic illness compared to other older adults.13,14 Yet, low-income, racial, and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive palliative care than non-Hispanic whites and those of higher incomes.10,15–17

One significant barrier to palliative care utilization is that it is primarily delivered in hospitals, and few outpatient or community-based palliative care services exist.9,18 Community providers’ role in delivering palliative care is unclear to patients, their caregivers, and to providers themselves, and there is often a lack of collaboration between health-care professionals around palliative care.19 There is also a lack of familiarity among both patients and providers regarding both what palliative care is (“palliative care” is often confused with hospice care20,21) and how to access existing palliative care services.9

Increasing screening for palliative care needs by community-based aging service agency providers is one simple, direct, and previously untested strategy to enhance palliative care service access for low-income, minority older adults in community settings. Community-based aging service agencies include meal services programs, case management agencies, respite services, adult day services programs, senior centers, housing developments, and naturally occurring retirement community (NORC) programs. Many aging service agency providers have established strong relationships with chronically ill older adults and their caregivers, and most agencies’ service missions align with the palliative care philosophy to enhance the quality of life for individuals and their families.22 There is also preliminary evidence that staff and clients will accept community-based palliative care initiatives embedded in aging service agencies.23,24 For example, the Harlem Palliative Care Network,25 a multidisciplinary collaborative, successfully partnered with over 150 community agencies and found that many agencies referred clients for palliative care over the course of the program.

However, identification and referral of eligible clients to palliative care by community providers26 are limited, and screening efforts of individuals with unmet palliative care needs are hampered by a lack of appropriate assessment tools. Although a recent Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality review identified many palliative care assessment tools developed for both inpatient and outpatient settings,27 none have been developed for community-dwelling older adults with chronic conditions served by aging service agencies. Moreover, most palliative care screening and assessment tools focus on only 1 type of need for palliative care, such as physical symptom burden.28–30 This is despite the fact that according to the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care,31 palliative care includes multiple domains, such as physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and cultural aspects of care. The very few multidomain tools that have been developed were designed for specific conditions (such as cancer) and/or for use by nurses and physicians,32–34 not for use by community senior service providers or for administration in adults with a range of chronic conditions.

The proposed research sought to address this gap by developing a new multidomain screening tool for older adults with a range of chronic illnesses and then training aging service agency providers to identify clients with palliative care needs and refer them for services at outpatient-based palliative care clinics, when appropriate. Our overarching goal was to facilitate engagement with the evidence-based practice of palliative care by community-based aging service agency providers and to enhance their clients’ health service access. The specific aims of the project were to (1) develop a multicomponent palliative care screening instrument for use among chronically ill older adults, (2) train community-based service providers in 2 different settings to administer the measure, (3) examine the feasibility of implementing the tool with community-based service providers and its acceptability to providers, (4) determine whether tool use is associated with referral to outpatient palliative care programs, and finally (5) estimate the costs of training staff and tool implementation in practice.

Materials and Methods

This project grew out of an ongoing academic-community partnership, the Brookdale-Weill Cornell Pallitative Care Consortium Consortium. The collaboration utilized a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, in which full community input was sought in all phases of the research process, from development to implementation to dissemination of findings.35 Community-based participatory research is designed to meet the needs of local communities and foster sustainable solutions.35 Notably, CBPR has been suggested as an ideal approach for tailoring assessment tools for specific populations36,37 and has been proposed as a tool to advance palliative care research.38

For several years, researchers and clinicians at The Brook-dale Center for Healthy Aging, Hunter College, CUNY and the Department of Geriatrics, Weill Cornell Medicine have worked in partnership with community members and elder service providers in the East and Central Harlem neighborhoods of New York City (NYC) through an established community advisory board of approximately 20 members. Predominantly Hispanic and African American, East and Central Harlem have a higher incidence of chronic illnesses than NYC as a whole and more than 30% of residents live in high poverty.39,40 Both neighborhoods are categorized by the Health Resources and Services Administration as Medically Underserved Areas.41 Previous projects evolving from the partnership included a community needs assessment23,42 and the development of a training curriculum on palliative care for elder service providers. This ongoing engagement demonstrates that there is unmet need for palliative care in East and Central Harlem and that aging service providers are interested in learning how to screen for and address palliative care needs in clients.23,42 All project procedures were approved by the institutional review board of City University of New York.

Screening Tool Development

We developed a brief, user-friendly screening tool containing 20 to 30 items that would take about 10 to 15 minutes to complete, following the procedures for scale development outlined by DeVellis.43 Domains covered by the tool were based on the 8 domains identified by the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Palliative Care.31 We simplified these into 4 broader domains that were most relevant to a community-based screening tool: physical symptoms, emotional concerns, goals of care, and family support needs. As recommended by DeVellis,43 we began by reviewing existing measures in the 4 primary domains and selected a limited number of items from each measure. We identified several screening tools that had been used in cancer treatment settings, and screens for various components of palliative care (eg, assessing symptom burden), but nothing that assessed several aspects of palliative care at once in a community setting. Next, items were reviewed for inclusion and word choice by a national advisory committee composed of 4 experts in palliative care, including senior faculty, policy analysts, and senior clinicians in nursing and social work from across the United States. We received feedback from the committee that assessing family caregiver needs would be difficult to measure reliably and validly in a tool administered only to clients. Therefore, we removed the “family support needs” domain from the tool and proceeded with a 3 domain measure. Measures reviewed for each domain are outlined in Table 1. Some symptoms that were key to these measures, such as weight changes, appetite changes, constipation, or nausea, were omitted both to keep the physical symptoms domain brief because they often co-occurred with other symptoms that were included or because they were thought by the expert panel to be less common than other symptoms.

Table 1.

Measures Reviewed for Palliative Care Screening Tool Development.

| Domain | Measures Reviewed |

|---|---|

| Physical symptoms | |

| Emotional concerns | |

| Goals of care |

Abbreviations: CAMPAS-R, Cambridge Palliative Assesment Schedule; CSNAT, Carer support Needs Assesment Tool; ESAS, Edmonton Symptoms Assesment System; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; SNST, Supportive Needs Screening Tool.

The 3-domain draft screening tool was further refined based on in-person focus groups with elder service providers in East/Central Harlem (n = 3) and older adults in East/Central Harlem (n = 30) in both English and Spanish; discussions included word choice to ensure comprehension and literacy. Finally, 2 older adults participated in-depth usability testing with the screening tool in the presence of a research assistant and one of the project leads. Notes were taken on items requiring clarification, concerns regarding content, time taken to complete, ease of reading, and word choice preferences. This input resulted in a 22-item, 1-page screening tool that could be implemented in about 10 minutes. Based on the feedback received from the expert panel, focus groups, and community advisory board, combined with the screen-positive rates in usability testing and the clinical expertise of the project team, it was determined that in order to screen positive, a person would have to have 2 or more items present most of/all the time, on all 3 of the domains. See Table 2 for the current version of the tool.

Table 2.

Palliative Care Screening Tool.

| Physical symptoms | |||

| Currently, are you bothered by the following? | Never | Sometimes | All the time |

| ○ Pain or physical discomfort | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Feeling tired, fatigued or having low energy | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Difficulty standing or walking | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Difficulty sleeping (sleeping too much or can’t sleep) | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Shortness of breath | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Emotional concerns | |||

| Currently, are you experiencing the following? | Never | Sometimes | All the time |

| ○ Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Not being able to stop or control worrying | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Having little interest or pleasure in usual activities | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Worried about being dependent, or a burden, on friends or family | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Feeling like there is no one in your life that you can talk to | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Having conflicts with friends or family | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Goals of care | |||

| Currently, are you experiencing the following? | Never | Sometimes | All the time |

| ○ Feeling overwhelmed about any medical treatment | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Feeling confused about your medical care | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Feeling uncomfortable asking questions about your care | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Feeling like you need access to more medical providers (doctors, nurses) | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Feeling like you need more information about other community resources | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Now I have a few questions about long term care planning | No | Yes | Don’t know |

| Have you given thought to how you want to be cared for when your illness(es) advance/as you age? | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you talked with anyone about how you want to be cared for? | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| If YES, do you have a document that indicates what your wishes are and who will make decisions for you? | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Do you have a Health Care Proxy? Note: A “Health Care Proxy” is a document with which an individual appoints someone to legally make healthcare decisions for them, in case they are ever unable to make and carry out the healthcare decisions | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| ○ Have you completed a Living Will? Note: A “Living Will” is a document that lets people state their wishes for end-of-life medical care, in case they ever become unable to communicate their wishes | 2 | 1 | 2 |

Provider Training

We utilized a 2-group posttest design to assess the feasibility and acceptability of implementing the tool as part of routine practice, collecting data from 16 elder service providers at 2 aging service agencies (8 at each site). Aging service providers (primarily masters-level social workers) were trained to administer the tool in single 60-minute in-person sessions, during time typically devoted to staff development. Partner sites included the Carter Burden Center for the Aging and Union Settlement. Carter Burden is a multiservice center, and the tool was implemented with providers at their new senior-focused adult day program, which is New York State’s first innovative Adult Day Program. The program provides housing as well as a range of programs and services including connections to community-based organizations. Union Settlement provides a variety of social services, including 4 senior centers, an NORC and transportation and nutritional assistance to homebound elders. Case managers at one of the senior centers participated in the project.

We asked providers to implement the tool with 5 to 10 clients over 3 months while conducting assessments that were already required as part of routine practice. Client eligibility criteria for screening tool receipt was English- or Spanish-speaking, age 60 or older, and with capacity to comprehend the screening tool (as determined by cognitive screens that are part of providers’ usual assessments). A checklist of common chronic conditions was also provided (eg, arthritis, asthma, chronic pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease) to identify participants’ chronic conditions. We instructed providers to refer screen positives to 2 local outpatient palliative care clinics that had agreed to receive referrals as part of this project. Providers were also given a brief information sheet with local resources to share with all screened clients who were interested in receiving them.

Measures

To measure the feasibility of screening tool implementation, we asked providers to complete a deidentified checklist with the following questions after each screening attempt whether clients accepted screening (and if not, why), whether clients who accepted screening screened positive, whether screen positives were referred to outpatient palliative care services, and whether the client accepted these referrals. All deidentified checklists were collected by the research team at the end of the 3-month pilot period. To measure acceptability of the training to providers, self-report acceptability measures were collected from providers immediately posttraining (in person), and 3-month posttraining (in person and online). As no standard acceptability measure for a palliative care assessment could be identified, we developed acceptability measures for this project, modeled after acceptability measures utilized in previous studies of provider trainings in unrelated topics.55,56 The acceptability items are outlined in Table 3. Finally, although the primary focus of the study was not on cost-effectiveness, we sought to obtain a rough estimate of the cost of implementing the tool. We estimated cost to the 2 participating aging service agencies based on staff time required to attend the training and conduct the screenings.

Table 3.

Provider Acceptability Items.

| Domains and Items | Posttraining % Agree/Strongly Agree (N = 15) n (%) |

3 Months Post % Agree/Strongly Agree (N = 12) n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure of the tool | ||||||

| The screening tool items are easy to understand | 15 (100.0) | 10 (83.3) | ||||

| The screening tool items are easy to read | 15 (100.0) | 11 (91.7) | ||||

| The screening tool items are logical | 14 (93.3) | 10 (83.3) | ||||

| The screening tool items are in a good order | 13 (86.7) | 9 (75.0) | ||||

| Just from reading it, I can see how I should use the screening tool | 13 (86.7) | 9 (75.0) | ||||

| The appearance and layout of the screening tool is clear | 15 (100.0) | 10 (83.3) | ||||

| The scoring system is confusing | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| The language used in the screening tool is too complex | 2 (13.3) | 1 (8.3) | ||||

| The screening tool tries to cover too much information | 3 (20.0) | 2 (16.7) | ||||

| The screening tool is confusing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | ||||

| The screening tool is too long | 1 (6.7) | 1 (8.3) | ||||

| Use of the tool | ||||||

| The screening tool is easy to use | 14 (93.3) | 9 (75.0) | ||||

| I think I will often use/I have often used the screening tool in my practice | 4 (26.7) | 3 (25.0) | ||||

| I feel comfortable administering the screening tool | 13 (86.7) | 11 (91.7) | ||||

| Attitudes towards the tool | ||||||

| The screening tool is useful for addressing clients’ palliative care needs | 12 (80.0) | 11 (91.7) | ||||

| The screening tool covers all important components of palliative care | 9 (60.0) | 10 (83.3) | ||||

| The screening tool seems relevant to my work | 8 (53.3) | 11 (91.7) | ||||

| My decision-making would be/is helped by using the screening tool | 8 (53.3) | 7 (58.3) | ||||

| The screening tool is a good choice for my setting | 9 (60.0) | 10 (83.3) | ||||

| I am concerned that this will open up questions that I can’t deal with | 2 (13.3) | 2 (16.7) | ||||

| I am concerned that this is something else being imposed my mangers that will not help me as a practitioner | 3 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| I already have too many forms to fill in and this will just add to them without helping me | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Posttraining | 3-Month posttraining | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Needs to be made simpler | Should be more detailed | Is just about right | Needs to be made simpler | Should be more detailed | Is just about right | |

|

| ||||||

| Overall, the whole tool: | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 10 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 2(16.7) | 10 (83.3) |

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each acceptability item and on the results of each deidentified checklist and on cost in provider time. Because all measures were deidentified, we were not able to match pre- and posttraining acceptability measures. Therefore, only frequency and percentages were calculated.

Results

Feasibility of Implementation and Acceptability to Providers

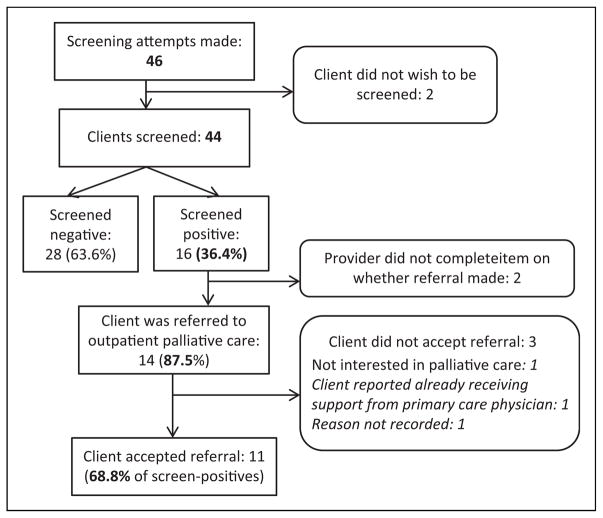

Implementation of the screening tool into routine practice was feasible. Trained providers attempted to administer the tool to a total of 46 clients over the 3-month implementation period, meeting our projected goals for the pilot. Almost all clients (n = 44; 95.65%) agreed to complete the assessment (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results of screening attempts.

A total of 15 of 16 trained providers completed the post-training acceptability (1 provider had to leave the training early due to a work responsibility) and 12 completed the 3-month follow-up. On the self-report provider acceptability survey, we found that the structure and use of the tool were acceptable to trained providers, immediately posttraining, and that acceptability was maintained at the 3-month follow-up, postimplementation. For example, 93.3% (n = 14) at posttraining and 75.0% (n = 9) at the 3-month follow-up said that the tool was easy to use, 80.0% (n = 12) at posttraining and 91.7% (n = 11) at 3-month follow-up said that the tool was useful for addressing clients’ palliative care needs, and 100.0% (n = 15) at post-training and 83.3% (n = 10) at the 3-month follow-up said that the screening tool items were easy to understand. Responses on each acceptability survey item are represented in Table 3.

On open-ended items both posttraining and at the 3-month follow-up, providers reported aspects that they liked most about the tool to include: “how easy it is to understand,” “I can get people to talk,” “It’s … to the point,” “Very helpful,” “It is short and clear,” and “The tool is clear and easy to use.” Several providers noted that they liked how it was broken down into different sections, and several also commented that they liked how “simple” it is. Contents of comments were similar both immediately posttraining and at the 3-month follow-up.

Aspects that participants liked least about the screening tool were that it “isn’t very detailed” and that it “may be too vague.” One provider had a concern about using a novel assessment, noting “it’s new learning to use it.” There were also concerns about length; providers reported that the tool “has maybe a few too many questions … it was hard for [clients] to sit through,” and one suggested that the screening tool be condensed further. Another provider noted “it gets me into difficult conversations.” A few commented that they wished some of the items were more detailed. Most of these concerns arose after providers had attempted to use the tool during the 3-month pilot period.

Providers also noted that there were a few barriers to implementing the tool, including “getting participants to focus on the questions rather than elaborating” and being uncertain about how to best follow-up with a positive screen. As one provider noted: “If further information is needed, [I] might not necessarily know the answer,” while another reported “Connecting the seniors to the next steps [was] … the hardest,” and another provider noted that they were concerned about the “actual logistics of care referrals,” and another asked for a more complete list of resources for clients. Providers also asked for “better communication and understanding within community organizations as to how the screening tool should be used and how we should be making appropriate referrals.” Providers stressed the importance of “making sure all participants understand Palliative Care.”

Referrals

A total of 44 clients were screened over the 3-month pilot period. Of these, 16 (36.4%) screened positive for palliative care need. Of the clients who screened positive, 87.5% were referred for palliative care services and the majority (68.8%; n = 11) accepted referrals. See Figure 1 for more detail.

Estimated Costs

The training was 60-minute long. At a rough salary estimate of USD$25/provider/hour, for the 16 providers who attended the training, the total cost for provider time to attend training was USD$400.00. Trained providers estimated that each screening tool took about 10 minutes to administer, on average. At an average salary estimate of USD$25/provider/hour, the total cost to administer 44 screening tools would be approximately USD$183. The total cost of implementing the tool for each participant, in provider time, was therefore approximately USD$583.

Discussion

This project is the first, to our knowledge, to develop a tool to identify chronically ill older adults with unmet palliative care needs in aging service agencies. We provide preliminary evidence that the tool is acceptable to providers and can be feasibly implemented into routine practice with minimal provider burden or cost to partner agencies. The tool was feasibly delivered to diverse, underserved populations in community settings. Establishing that the screening tool can be adopted and utilized by aging service providers is a necessary first step before moving forward with larger scale testing and dissemination. Community-based providers may be able to identify elders with unmet needs for palliative care, address psychosocial barriers to utilization, and coordinate service access in ways that primary care and hospital providers cannot. Therefore, the newly developed screening tool can be used to identify older adults who might benefit from palliative care and facilitate the provision of appropriate care. For example, work has shown that palliative care consultations and education can positively influence advance care planning and acceptance of symptom management.36

Appropriate assessment is necessary to reduce disparities and increase access to palliative care for older adults with chronic illnesses, particularly racial and ethnic minorities in underserved communities.17 Screening tool domains in the newly developed measure are consistent both with National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines and a range of other palliative care assessment tools. We also used a similar development and piloting process to other palliative care measures.32 Yet this is among the first multidomain tools; the few other multidomain tools were developed specifically for patients with cancer who may have different palliative care needs than those with other chronic illnesses.32–34

Facilitators of this project included the transdisciplinary expertise and combined research experience of the Brookdale-Weill Cornell Pallitative Care Consortium Consortium’s academic-community partnership and our ongoing partnership with a committed group of Harlem-based older residents and providers through our community-based participatory approach. Developing the screening tool in partnership with community members and pilot testing at 2 different community sites, coupled with the low costs of minimal training to use the tool, should enhance its long-term sustainability.

Limitations

The project has several limitations. First, our sample of trained providers and clients was small. Although consistent with the goals of a pilot project, future work should train additional providers and administer the tool to a larger number of clients, over a longer period. Not all clients seen by trained providers were administered the screening tool, which may have biased findings. As our focus was on provider training, rather than client use, we did not collect data on any client sociodemographic or clinical factors associated with screening tool administration or with screen-positive rates. There may also be variation in who received the screening tool by provider or site, but data collection did not allow us to explore these questions. The lack of client-level data also prevented us from examining client’s follow-up on referrals to outpatient palliative care clinics, whether clients accepting referrals were ever evaluated by palliative care clinic teams or the results of such referrals. Future work should collect client-level data on factors associated with screening positive on the measure and on utilization of palliative care services. In addition, our “screen positive” rates were based on clinical judgement and initial feedback from expert panel members, providers, and older adults, not on comparison with any gold standard of palliative care eligibility. Scoring positive on 2 of the 3 domains might be equally valid, for example. Future work is needed to establish valid and reliable cutoff scores for the measure, and to establish the tool’s concurrent validity, test–retest reliability, and discriminant validity. In addition, the screening tool does not cover all of the domains recommended by the National Consensus Project Guidelines,27 such as family needs. Further, while we reviewed items closely with older adults in our communities of focus, and reworded some items, we did not measure older adult participants’ health literacy using standardized measures.57 Future work should consider how health literacy affects screening tool use. Finally, participants were service recipients from 2 aging service agencies in East and Central Harlem in NYC. Results cannot be generalized to other populations of aging service agency clients.

There were also some challenges in incorporating the tool and trainings into providers’ already busy schedules. Although designed to be efficient and minimally burdensome, some providers still had some concerns about the length of the tool, and some remained unsure how well palliative care fit into their work. Other providers expressed a wish for the tool to be more specific and detailed. More details on how best to follow up and on resources to connect clients were also needed. In future implementation, we will likely remove some items and make other items slightly more specific and provide more guidance on pathways and resources for follow-up and referral.

Next Steps

Both aging service agency partners and several other community-based providers who participated in our Consortium have expressed interest in continuing to use the screening tool, particularly if it can be better integrated into existing assessments they are required to conduct by the NYC Department for the Aging. We plan to continue meeting with administrators to facilitate this process. Based on provider feedback, the tool may be further refined before larger scale testing.

In future work, we will seek to train additional providers in its use and to have the tool administered to additional clients. Additional provider and client participation would provide a large enough sample to establish the reliability and validity of the new screening tool. As one option, a palliative care team could administer the tool to patients and compare findings to their “gold standard” clinical assessment. Future work could focus on gathering data on clinical outcomes for clients who receive the tool. During piloting, there was also some discussion about whether the tool could be made available as a self-report measure; future work could examine administration in this form.

Our long-term goal is to facilitate the transfer of the tool both locally and nationally, across a larger number of sites, and types of sites (eg, NORCs, Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly programs, faith-based organizations). The tool could also be integrated into broader efforts to connect vulnerable older adults to needed health and mental health services; researchers and staff at the NYC Department for the Aging recently developed the “Mobilization, Assessment, Referral, and Treatment for Mental Health” to screen older adults at senior centers, faith-based organizations, and community organizations, living in areas impacted by Hurricane Sandy-impacted areas of NYC for social service and mental health needs and to connect those who screened positive to services,58–60 for example. Future work might also consider the use of the tool beyond aging service agencies (eg, in primary care or other outpatient settings). Increased screening in community settings is consistent with guidelines recently developed in both cancer61 and other chronic disease62 care to promote integration of palliative care with existing services.

Finally, a lack of assessments of cultural aspects of care (including cultural competence) in palliative care has been noted; the AHRQ review could not identify any assessment tools focusing on the cultural domain of the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care.27 Future research could better integrate this domain into our, and other, palliative care tools.

Conclusion

Our new palliative care screening tool shows evidence of feasibility and acceptability with community-based elder service providers working with diverse, underserved populations. The tool should be validated and more broadly disseminated in future work. In the long term, the tool has high potential to transform how we educate nonclinical providers about palliative care and identify and connect chronically ill older adults with palliative care services, with the potential for improving quality of life in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the John A. Hartford Foundation for their support of this project. The authors would also like to thank our Community Advisory Board Members, our expert panel members, and all leadership, staff, and clients at the Carter Burden Center for the Aging and Union Settlement who assisted us with this project, particularly William Dionne, Dozene Guishard, Maria Alejandro, and David Nocenti.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project was funded by a change AGEnts grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. The State of Aging and Health in America, 2013. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2013. [Accessed August 25, 2014]. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/state-aging-health-in-america-2013.pdf. Updated December 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walke LM, Gallo WT, Tinetti ME, Fried TR. The burden of symptoms among community-dwelling older persons with advanced chronic disease. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(21):2321–2324. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.21.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moens K, Higginson IJ, Harding R Euro Impact. Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(4):660–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckerblad J, Theander K, Ekdahl A, et al. Symptom burden in community-dwelling older people with multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-15-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center to Advance Palliative Care. Palliative Care and Hospice Care across the Continuum. New York, NY: CAPC; 2014. [Accessed December 1, 2014]. http://www.capc.org/palliative-care-across-the-continuum/. Updated December 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higginson IJ, Hearn J. A multicenter evaluation of cancer pain control by palliative care teams. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(97)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(1):83–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez-Batiste X, Martinez-Munoz M, Blay C, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of patients with advanced chronic conditions in need of palliative care in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Palliat Med. 2014;28(4):302–311. doi: 10.1177/0269216313518266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyes-Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Shete S, Bruera E, Yennuraja-lingam S. Early referral to supportive care specialists for symptom burden in lung cancer patients: a comparison of non-hispanic whites, hispanics, and non-hispanic blacks. Cancer. 2012;118(3):856–863. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care for cancer patients in a cluster randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(4):593–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center Health Statistics. Health, United States 2015. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015, with Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Disparities. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2015. [Accessed August 16, 2017]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf. Updated December 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kayser K, DeMarco RF, Stokes C, DeSanto-Madeya S, Higgins PC. Delivering palliative care to patients and caregivers in inner-city communities: challenges and opportunities. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(5):369–378. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyckholm LJ, Coyne PJ, Kreutzer KO, Ramakrishnan V, Smith TJ. Barriers to effective palliative care for low-income patients in late stages of cancer: report of a study and strategies for defining and conquering the barriers. Nurs Clin North Am. 2010;45(3):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329–1334. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawley L, Payne R, Bolden J, Payne T, Washington P, Williams S. Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2518–2521. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oishi A, Murtagh FE. The challenges of uncertainty and inter-professional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: a systematic review of views from patients, carers and health-care professionals. Palliat Med. 2014;28(9):1081–1098. doi: 10.1177/0269216314531999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):659–685. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1564-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lem AA, Schwartz M. African American heart failure patients’ perspective on palliative care in the outpatient setting. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2014;16(8):536–542. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Accessed March 3, 2015]. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Update December 8. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parikh NS, Villanueva C, Kenien C, et al. Results from a community needs assessment: addressing palliative care in diverse populations. Gerontologist. 2014;54(suppl 2):128. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobrof J, Heyman JC, Greenberg RM. Building on community assets to improve palliative and end-of-life care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2011;7(1):5–13. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2011.548044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne R, Payne TR. The Harlem Palliative Care Network. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(5):781–792. doi: 10.1089/109662102320880705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(4):855–860. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Assessment Tools for Palliative Care. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The memorial symptom assessment scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorman S, Byrne A, Edwards A. Which measurement scales should we use to measure breathlessness in palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21(3):177–191. doi: 10.1177/0269216307076398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2015. [Accessed June 7, 2017]. http://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org. Updated December 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pigott C, Pollard A, Thomson K, Aranda S. Unmet needs in cancer patients: development of a supportive needs screening tool (snst) Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(1):33–45. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glare PA, Chow K. Validation of a simple screening tool for identifying unmet palliative care needs in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2014;11(1):e81–e86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glare PA, Semple D, Stabler SM, Saltz LB. Palliative care in the outpatient oncology setting: evaluation of a practical set of referral criteria. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(6):366–370. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Head BA, LaJoie S, Augustine-Smith L, et al. Palliative care case management: increasing access to community-based palliative care for medicaid recipients. Prof Case Manag. 2010;15(4):206–217. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181d18a9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziviani J, Darlington Y, Feeney R, Head B. From policy to practice: a program logic approach to describing the implementation of early intervention services for children with physical disability. Eval Program Plann. 2011;34(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riffin C, Kenien C, Ghesquiere A, et al. Community-based participatory research: understanding a promising approach to addressing knowledge gaps in palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2016;5(3):218–224. doi: 10.21037/apm.2016.05.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. [Accessed December 8, 2017];Community health profiles 2015. Manhattan Community District 11: East Harlem. 2015 http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015chp-mn11.pdf.

- 40.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. [Accessed December 8, 2017];Community health profiles 2015. Manhattan Community District 10: Central Harlem. 2015 http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015chpmn11.pdf.

- 41.Health Resources and Services Administration. Shortage designation: Health Professional Shortage Areas & Medically Under-served Areas/Populations. Choctaw, MS: 2015. [Accessed December 4, 2015]. http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/geoadvisor/ShortageDesignationAdvisor.aspx. Updated December 8, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parikh NS, Gardner DS, Villanueva C, et al. Assessing the palliative care needs of chronically-ill older adults in East and Central Harlem. In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeVellis RF. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Vol. 26. New York, NY: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ewing G, Todd C, Rogers M, Barclay S, McCabe J, Martin A. Validation of a symptom measure suitable for use among palliative care patients in the community: CAMPAS-R. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27(4):287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the brief fatigue inventory. Cancer. 1999;85(5):1186–1196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levy MH, Adolph MD, Back A, et al. Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10(10):1284–1309. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F. The McGill Quality Of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. a preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995;9(3):207–219. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Cancer Care Network. [Accessed March 3, 2015];NCCN Distress Thermometer for Patients. 2013 http://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_with_cancer/pdf/nccn_distress_thermometer.pdf. Updated December 8, 2017.

- 50.Osse BH, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Schade E, Grol RP. A practical instrument to explore patients’ needs in palliative care: the problems and needs in palliative care questionnaire short version. Palliat Med. 2007;21(5):391–399. doi: 10.1177/0269216307078300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ewing G, Brundle C, Payne S, Grande G National association for hospice at h. the carer support needs assessment tool (csnat) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: a validation study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emanuel LL, Alpert HR, Emanuel EE. Concise screening questions for clinical assessments of terminal care: the needs near the end-of-life care screening tool. J Palliat Med. 2001;4(4):465–474. doi: 10.1089/109662101753381601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the center to advance palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vandelanotte C, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Acceptability and feasibility of a computer-tailored physical activity intervention using stages of change: project faith. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(3):304–317. doi: 10.1093/her/cyf027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hides L, Lubman DI, Elkins K, Catania LS, Rogers N. Feasibility and acceptability of a mental health screening tool and training programme in the youth alcohol and other drug (aod) sector. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(5):509–515. doi: 10.1080/09595230701499126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serper M, Patzer RE, Curtis LM, et al. Health literacy, cognitive ability, and functional health status among older adults. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(4):1249–1267. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sirey JA, Berman J, Halkett A, et al. Storm impact and depression among older adults living in hurricane sandy-affected areas. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017;11(1):97–109. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sirey J, Raue P, Giunta N, Berman J. SMART-MH: improving access to services and delivery of mental health care to older NYC victims of superstorm sandy. Gerontologist. 2015;55(suppl 2):707–707. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giunta N, Berman J, Glushefski R, Sirey J. Community outreach to superstorm sandy survivors: a process & outcome evaluation of SMART-MH. Gerontologist. 2015;55(suppl 2):433–434. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society Of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96–112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siouta N, Van Beek K, van der Eerden ME, et al. Integrated palliative care in Europe: a qualitative systematic literature review of empirically-tested models in cancer and chronic disease. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:56. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0130-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]