Abstract

Dietary supplement and natural product use is increasing within the United States, resulting in growing concern for exposure in vulnerable populations, including young adults and women of child-bearing potential. Vinpocetine is a semi-synthetic derivative of the Vinca minor extract, vincamine. Human exposure to vinpocetine occurs through its use as a dietary supplement for its purported nootropic and neuroprotective effects. To investigate the effects of vinpocetine on embryo-fetal development, groups of 25 pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats and 8 pregnant New Zealand White rabbits were orally administered 0, 5, 20, or 60 mg vinpocetine/kg and 0, 25, 75, 150, or 300 mg/kg daily from gestational day (GD) 6-20 and GD 7-28, respectively. Pregnant rats dosed with vinpocetine demonstrated dose-dependent increases in post-implantation loss, higher frequency of early and total resorptions, lower fetal body weights, and fewer live fetuses following administration of 60 mg/kg, in the absence of maternal toxicity. Additionally, the rat fetuses displayed dose-dependent increases in the incidences of ventricular septum defects and full supernumerary thoracolumbar ribs. Similarly, albeit at higher doses than the rats, pregnant rabbits administered vinpocetine displayed an increase in post-implantation loss and fewer live fetuses (300 mg/kg), in addition to significantly lower fetal body weights (≥ 75 mg/kg). In conclusion, vinpocetine exposure resulted in similar effects on embryo-fetal development in the rat and rabbit. The species differences in sensitivity and magnitude of response is likely attributable to a species difference in metabolism. Taken together, these data suggest a potential hazard for pregnant women who may be taking vinpocetine.

Keywords: vinpocetine, dietary supplements, embryo-fetal development, embryotoxicity, fetal malformations, rat, rabbit

1. Introduction

Vinpocetine is semi-synthetic product that is derived from vincamine, an alkaloid extract from the periwinkle plant, Vinca minor. Unlike other botanical dietary supplements, vinpocetine is not a mixture or an extract, but a synthesized product with high purity. While vinpocetine is not a mixture itself, it is often sold in combination with other botanicals such as Ginkgo biloba. Vinpocetine has been widely available as a pharmaceutical agent in Europe, Russia, China, and Japan since the late 1970s for treatment of cerebrovascular and cognitive disorders (Bereczki and Fekete, 2008). In the United States, vinpocetine is mainly marketed as a dietary supplement with the primary purported indication of cognitive enhancement, including use as treatment for Alzheimer’s, dementia, and ischemic stroke (Thal, 1989; Szatmari and Whitehouse, 2009; Peruzza and Dejacobis, 1986; Maconi, 1986; Feigin, 2001; Bereczki and Fekete, 2008). Though original indications for vinpocetine promoted its use in the elderly, several products are currently available that are specifically marketed towards students as supplements for increasing cognitive performance (Ley, 2000). Additionally, vinpocetine has been used among healthy athletes within the body building community for reported enhancement of visual acuity, memory, and focus. Other reported uses include treatment for vertigo, urinary incontinence, tinnitus, Meniere’s disease, visual impairment, menopause symptoms, chronic fatigue syndrome, seizure disorders, and for prevention of motion sickness (Anonymous, 1984; Sitges, 2016; Taiji and Kanzanki, 1986; Thorne, 2002; Truss, 2000).

Human exposure to vinpocetine occurs through oral consumption. In the United States vinpocetine products are available in dosages ranging from 5 to 30 mg, with recommended uses of 1 to 3 times daily; these dosages equate to daily doses of 5 to 90 mg. However, a recent analysis of vinpocetine supplements demonstrates a common problem with dietary supplements, where 6 out of the 23 (17%) sampled supplements contained no vinpocetine and in those that did contain vinpocetine the actual vinpocetine content varied from what was stated on the label (Avula, 2015). This results in differences in total daily consumption rates, with the potential for higher dosages than what is recommended by the product labels.

Previous assessments of the potential developmental and reproductive toxicity of vinpocetine are limited to safety test data not available to the public that are summarized in a single publication by Cholnoky and Dömök (1976). This publication included limited information on study design parameters and details on outcomes from four teratology studies in the rat, where dosing occurred over the major period of organogenesis. In these studies, pregnant female rats (n = 10 to 24 per group depending on the study) were administered doses of vinpocetine that ranged from 12.5 to 150 mg/kg body weight. Adverse maternal outcomes across these studies included deaths, significant decreases in body weight gain, and vaginal (uterine) bleeding. Complete litter resorptions occurred at the higher administered doses. In the fetuses, the major findings across these studies were conflicting, with studies indicating fetal death and/or growth retardation or no adverse fetal outcomes with doses up to 150 mg/kg. Cholnoky and Dömök (1976) also included limited summary information on a single teratology study performed in rabbits. In this study, pregnant does (n = 14 to 15 per group) were orally administered 0, 6, 12, and 18 mg/kg vinpocetine from GD 6 to 18. Aside from a small statistically significant reduction in body weight gain in the high dose group, no other maternal toxicity was noted. No adverse fetal effects were observed, and although no specific numbers were provided, the authors noted that abortion and complete litter loss in the dosed groups were comparable to controls.

Given the widespread potential use of vinpocetine by women of childbearing potential, and the apparent signals of developmental toxicity in the limited publicly available literature, studies were conducted by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) in Sprague Dawley rats and New Zealand White rabbits to characterize the potential effects of vinpocetine exposure on embryo-fetal development. Here, we describe the developmental effects resulting from an embryo-fetal development study in rats and a dose-range finding study in pregnant rabbits. Species differences in developmental effects were identified in these studies and were put into perspective using systemic exposure and fetal transfer data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemical

Vinpocetine (VIN, lot # VA201211001) was obtained from Maypro Industries LLC (Purchase, NY). The chemical identity of the lot was confirmed by infrared spectroscopy, proton and carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and optical rotation analyses. The purity was determined to be > 99% based on both gas chromatography with flame ionization detection and high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection (230nm).

2.2 Animals and Housing

Time-mated female Hsd:Sprague Dawley® SD® (GD 0 assigned as day evidence of mating was observed) were obtained from Harlan Laboratories, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were individually housed in solid-bottom polycarbonate cages and provided a certified rodent diet (Irradiated NIH-07; Zeigler Bros., Gardners, PA) and water ad libitum (City of Birmingham, AL municipal water). Rats were approximately 12 to 13 weeks old and ranged between 221 to 274 g at the time of mating. Time-mated New Zealand White rabbits (GD 0 assigned as day of mating) were obtained from Covance Research Products (Greenfield, IN). Animals were individually housed in perforated-bottom stainless steel cages and provided 150 g/day of certified rabbit diet (Purina 5322, 5LMO, Purina, Richmond, IN; or Teklad 2031C, Harlan, Madison, WI) with Timothy Hay for enrichment and water ad libitum (City of Birmingham, AL municipal water). Rabbits were approximately 5 to 6 months old and ranged from 2.7 to 3.5 kg at the initiation of dosing. Environmental conditions were set to maintain temperature between 69 and 75°F with 35 to 65% relative humidity or 61 and 72°F and 30 to 70% relative humidity, for rats and rabbits, respectively. Room lighting was set to provide a 12-hour light/dark cycle.

Animal care and use were in accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Animals. The studies were performed in compliance with the Food and Drug Administration Good Laboratory Practice Regulation (Food and Drug Administration 1987) at Southern Research (Birmingham, AL), an animal facility accredited by Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Studies were approved by Southern Research Institute’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with all relevant National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NTP animal care and use policies and applicable federal, state and local regulations and guidelines.

2.3 Group Designation and Dosing

Rats and rabbits were randomly assigned to dose groups based on GD 3 body weight stratification. Groups of 25 pregnant rats were administered 0 (vehicle control; 0.5% w/v aqueous methylcellulose), 5, 20, and 60 mg vinpocetine/kg body weight per day by oral gavage at a dose volume of 5 mL/kg from GD 6 to 20. These doses were based on a dose-range finding study conducted at exposure levels of 0, 20, 40, 80, 160, or 320 mg/kg), where embryo-fetal loss was observed at all doses examined with a steep dose-response in the incidence of fetal resorptions between 40 and 80 mg/kg/day (26% and 98% fetal resorptions, respectively). Groups of 8 pregnant rabbits were administered 0 (vehicle control; 0.5% w/v methylcellulose), 25, 75, 150, or 300 mg/kg per day by oral gavage at a dose volume of 5 mL/kg from GD 7 to 28. Rabbit doses were based on both the results from the rat prenatal development studies and on limited toxicokinetic data on vinpocetine in rats and rabbits from the literature demonstrating similar plasma AUC and Cmax levels between the species (Xu, 2009; Nie, 2006; Ribeiro, 2004; Sozanski, 2011; Vereczkey, 1979; Xia, 2010).

All animals were observed at least twice daily for signs of moribundity and mortality. In the rat study, body weights were measured daily from GD 6 to 21 and food consumption was measured every three days beginning on GD 3. Body weights and food consumption was measured daily in the rabbits, beginning on GD 3. Rats and rabbits were euthanized on GD 21 and 29, respectively, subjected to a laparotomy and underwent gross examination of abdominal and thoracic viscera. The gravid uterus was removed and weighed and the number of corpora lutea in each ovary, and the number, type, and position of implantation sites were recorded. Uteri with no visible implantation sites were placed in a 10% w/v aqueous solution of ammonium sulfide to detect early resorptions.

Viable fetuses were removed from the uteri and weighed individually. Placental morphology was also evaluated. A detailed external examination of each fetus was conducted, including assessment of palatal closure and determination of sex. The fetuses were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital solution. External (rat and rabbit), visceral (rat), and skeletal (rat) fetal findings were recorded as developmental variations or malformations (Makris, 2009). All rat fetuses in each litter were examined for soft-tissue alterations under a stereomicroscope (Staples, 1974; Stuckhardt and Poppe, 1984). The heads were removed from approximately half of the rat fetuses in each litter and fixed in Bouin’s solution and subsequently examined by free-hand sectioning (Thompson, 1967). Rat fetuses were eviscerated, fixed in ethanol, macerated in potassium hydroxide, stained with alcian blue and alizarin red, and examined for cartilage and osseous alterations (Kimmel and Trammell, 1981).

2.4 Analysis of Vinpocetine and Apovincaminic Acid in Rabbit Plasma

Does (n=4) were randomly selected from all groups for blood collection. Limited toxicokinetic data on vinpocetine in rabbits from the literature demonstrated that plasma Cmax is reached between 1 and 2 h and hence these time points were selected to evaluate plasma levels of vinpocetine and apovincaminic acid (AVA) in rabbits and compared to previously published rat data (Waidyanatha et al., 2017). Following vinpocetine administration on GD 19, blood was collected via the ear vein using K3EDTA at 1 and 2 h. Immediately following collection, tubes were mixed gently and placed on wet ice. Plasma was isolated from blood within 30 min of collection and frozen at -70 °C.

A method previously reported for rat plasma (Waidyanatha et al., 2017) using protein precipitation followed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry was cross validated to rabbit plasma to quantitate vinpocetine and apovincaminic acid (AVA) over the concentration range 0.5 to 100 ng/mL. This method was linear (≥ 0.99), accurate (% relative error, -6.4 to 9.7) and precise (% relative standard deviation, 1.3 to 12.3) for both vinpocetine and AVA in rabbit plasma. The limits of detection and quantitation, respectively, were 0.076 and 0.50 ng/mL for vinpocetine and 0.089 and 0.50 ng/mL for AVA. Matrix standards as high as 1,000 ng/mL could successfully be diluted into the validated concentration range (% relative error, 7.8 to 11.8; % relative standard deviation, 4.7 to 5.8). Vinpocetine and AVA was stable in rabbit plasma for at least 56 d when stored ~ -70°C d (% RE -11.5 to -0.5).

Each study plasma sample set was bracketed by method blanks, matrix calibration standards, and quality control (QC) samples prepared at low and high ends of the calibration curve. Data from study samples were considered valid if: the matrix calibration curve was linear (r ≥ 0.99); at least 75% of matrix standards were within 15% of nominal (except at the limit of quantitation where it was 20%); at least 67% of the QC samples were within 15% of nominal values.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed on data from pregnant females that survived until the end of the study and were examined on GD 21 (rat) or GD 29 (rabbits) and from live fetuses, using Instem Provantis® software and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Maternal organ and body weight data, which have approximately normal distributions, were analyzed with the parametric multiple comparison procedures of Dunnett (1955) and Williams (1971, 1972). Non-normally distributed variables, such as food consumption and uterine content endpoints, were analyzed using the nonparametric multiple comparison methods of Shirley (1977) (as modified by Williams, 1986) and Dunn (1964). For normally distributed and non-normally distributed variables, Jonckheere’s test (Jonckheere, 1954) was used to assess the significance of dose-related trends at p < 0.01 to determine whether a trend-sensitive test (Williams’ or Shirley’s test) was more appropriate than a test that does not assume a monotonic dose-related trend (Dunnett’s or Dunn’s test). Prior to statistical analysis, extreme values identified by the outlier test of Dixon and Massey (1957) were examined by NTP personnel, and implausible values were eliminated from the analysis.

Post-implantation loss was calculated as a percentage of the number of implants per dam or doe. Incidences of numbers of fetuses affected were analyzed using mixed effects logistic regression in which the litter was a random effect in order to account for potential litter effects (Zorilla, 1996; Pendergast et al., 2005; Li et al., 2011). For each fetal finding, an initial mixed effects logistic regression model incorporated dose as its numeric value to assess the significance of a dose-related trend; a subsequent logistic regression model incorporated dose as a categorical variable to assess the significance of contrasts of each dose group with the control group. Incidences of numbers of litters affected were analyzed using the Cochran-Armitage trend test (Armitage, 1955) and Fisher’s exact test (Gart et al., 1979).

Fetal body weights were analyzed using mixed effects linear models, with litter as a random effect to account for potential within-litter correlations. To test for a linear trend, dose was entered into the model as its numeric value and its significance was evaluated. For pairwise comparisons with the control group, a second mixed effects model with dose entered into the model as a categorical variable was estimated, followed by the Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Fetal body weights adjusted for litter size were analyzed using the Jonckheere’s test for trend followed by the multiple comparisons procedure of William’s or Dunnett’s, similar to the maternal body weights. Adjusted fetal weights were calculated by analysis of covariance in a manner similar to in-life adjusted maternal body weights, adjusting to the overall mean number of live fetuses on GD 21 for rats or GD 29 for rabbits.

3. Results

3.1 Rat embryo-fetal development

Exposure-related clinical observations were noted in the 20 and 60 mg/kg dose groups and were limited to a dose-related increase in the incidences of abnormal vaginal discharge (red and/or brown) (data available online; NTP, 2017). Observations of abnormal vaginal discharge generally began on GD 13 and continued until GD 18.

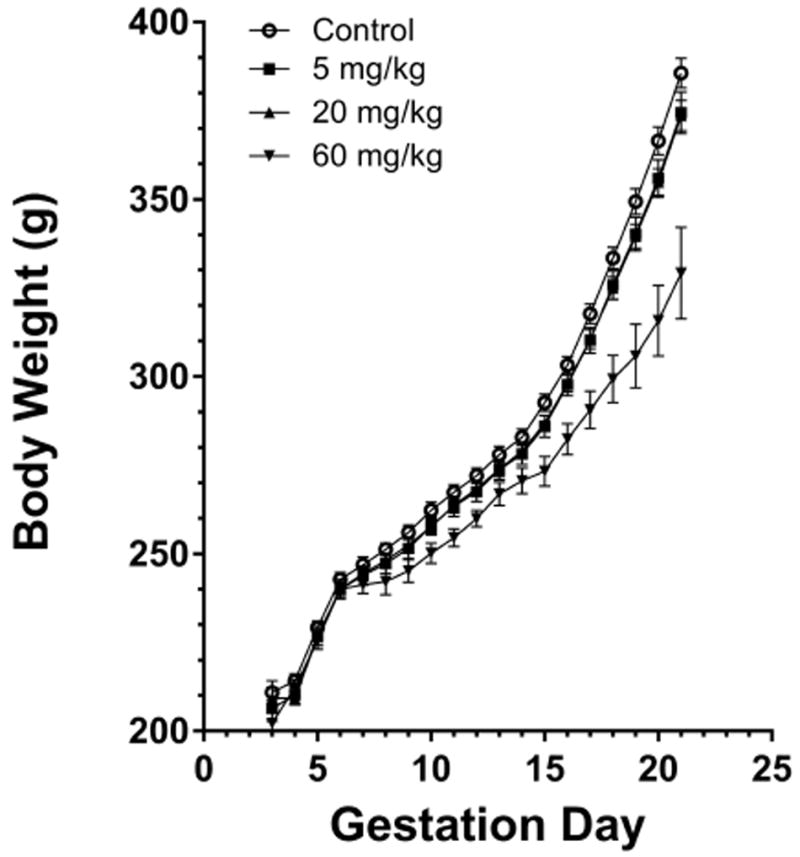

Body weight and food consumption data are displayed in (Table 1 and Figure 1). In the 60 mg/kg dose group, mean maternal bodyweights were lower throughout gestation (4 to 23% lower, beginning on GD 8, as compared to controls) with a significant decrease in maternal body weight gain from GD 6 to 21 (61% lower as compared to body weight gains in the controls), as a result of significant post-implantation loss. Transient decreases in mean food consumption occurred throughout the dosing period in the 60 mg/kg dose group and ranged from 8 to 17% lower relative to controls. There was no exposure-related effect on maternal body weights, weight gains, or food consumption in the 5 or 20 mg/kg dose groups.

Table 1.

Dam body weight gain and food consumption

| Dose (mg/kg)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 20 | 60 | |

| Number of Pregnant Dams | 21 | 20 | 22 | 20 |

| Body Weight Gaina | ||||

| GD 6 - 21 | 142.8 ± 3.4** | 128.7 ± 7.4 | 130.0 ± 5.1 | 55.3 ± 7.9** |

| GD 21 Bodyweight (g)b | 385.7 ± 4.2** | 368.5 ± 8.2 | 370.0 ± 5.5 | 296.1 ± 8.2** |

| Gravid Uterine Weight (g)b | 97.8 ± 3.1** | 83.9 ± 6.6 | 85.1 ± 5.3 | 19.5 ± 6.5** |

| Food Consumption (g)a | ||||

| GD 6 - 21 | 22.0 ± 0.3** | 21.6 ± 0.4 | 22.2 ± 0.3 | 19.9 ± 0.4** |

Data are displayed as mean ± standard error and do not include non-pregnant animals.

(g) = grams; GD = Gestation Day.

Statistically significant (P≤0.01) trend (denoted in vehicle control column) or pairwise comparison (denoted is dosed group column).

Statistical analysis performed by Jonckheere’s test (trend) and Williams’ or Dunnett’s test (pairwise). Body weight gains and food consumption for pregnant animals are given in grams/day and grams/animal/day, respectively.

Statistical analysis performed using the random effects model (trend and pairwise).

Figure 1.

Rat maternal body weight throughout gestation.

There was no difference in the number of pregnant females, the mean number of corpora lutea, and the number of implantation sites, which were similar across groups (Table 2). Percent pre-implantation loss appeared to be higher in the vinpocetine exposed dams (20%, 18%, and 22% in the 5, 20, and 60 mg/kg dose groups, respectively, compared to 8% in the controls) and might have contributed to fewer fetuses; however, this cannot be attributed to vinpocetine exposure as dosing was initiated after implantation occurred. Dams in the 60 mg/kg dose group displayed significant post-implantation loss (83.1% compared to 3.3% in controls) as a result of resorption of entire litters in 12 of the dams and increased incidences of resorptions in 7 of the dams. As a result of the increased post-implantation loss, there were fewer live fetuses per litter in the 60 mg/kg dose group (mean number of live fetuses per litter was 2.6 compared to 14.0 in the controls and the total number of fetuses for evaluation was 51 in the 60 mg/kg dose group as compared to 293 in controls), which was correlated with an 80% decrease in gravid uterine weight in this group (Tables 1 and 2). The 5 and 20 mg/kg dose groups displayed slightly higher mean percent post-implantation loss, relative to controls (10.7% and 11.1%, respectively), and each dose group had one dam with a whole litter resorption.

Table 2.

Dam Cesarean section observations and fetal weights

| Dose (mg/kg)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 20 | 60 | |

| Number of Pregnant Dams | 21 | 20 | 22 | 20 |

| Corpora luteaa | 15.9 ± 0.6 | 16.0 ± 0.7 | 15.4 ± 0.4 | 16.7 ± 0.4 |

| Implantation sitesa | 14.4 ± 0.5 | 12.6 ± 0.9 | 12.8 ± 0.9 | 13.0 ± 1.0 |

| Pre-implantation loss (%)a | 8.2 ± 2.8 | 19.5 ± 5.7 | 17.9 ± 4.9 | 22.1 ± 6.4 |

| Early resorptionsb | 0.3 ± 0.1** | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 10.4 ± 1.2** |

| Late resorptionsb | 0.05 ± 0.05 | 0 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0 |

| Whole litter resorptionsc | 0** | 1 | 1 | 12** |

| Post-implantation loss (%)a | 3.3 ± 1.3** | 10.7 ± 5.3 | 11.1 ± 4.7 | 83.1 ± 6.5** |

| Viable fetuses | 293 | 239 | 261 | 51 |

| Live fetuses/littera | 14.0 ± 0.6** | 12.0 ± 1.1 | 11.9 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 1.0** |

| Sex ratio (% male)a | 46.5 | 41.6 | 45.7 | 82.2* |

| Fetal weight (g)b | 5.15 ± 0.07 | 5.29 ± 0.16 | 5.21 ± 0.12 | 5.11 ± 0.10 |

| Adjusted fetal weight (g)d | 5.20 ± 0.02** | 5.12 ± 0.03* | 5.08 ± 0.03** | 4.58 ± 0.05** |

Data are displayed as mean ± standard error and do not include non-pregnant animals (n = 25 presumed pregnant dams were assigned per group).

(g) = grams.

Statistically significant (P≤0.05) trend (denoted in vehicle control column) or pairwise comparison (denoted in dosed group column);

(P≤0.01).

Statistical analysis performed by Jonckheere’s test (trend) and Shirley’s or Dunn’s (pairwise).

Statistical analysis performed using the random effects model (trend and pairwise).

Statistical analysis performed by Cochran-Armitage (trend) and Fisher exact (pairwise) tests.

Litter weights adjusted for litter size. Statistical analysis performed by Jonckheere’s test (trend) and Williams’ or Dunnett’s (pairwise) tests.

There was no exposure-related effect on fetal body weights (male or female) (Table 2). However, there were exposure-related decreases in adjusted mean fetal weights per litter in the 5, 20, and 60 mg/kg dose groups, with adjusted mean fetal weights 1.5%, 2.3%, and 12% lower than controls, respectively. The fetal-sex ratio appeared to be skewed in the 60 mg/kg dose group (82% male compared to 46% in controls); however, these results are based on the small number of viable litters and fetuses in this group and thus were considered spurious.

There were no fetal external abnormalities related to vinpocetine exposure. Exposure-related effects on rat visceral and skeletal development are presented in Tables 3 and 4, along with associated malformations and variations not attributable to exposure (individual fetal data available online; NTP, 2017). Visceral exposure-related findings included increased incidences of ventricular septum defects (VSDs), a malformation, which occurred in 0%, 1.3%, 3.1%, and 3.9% of the fetuses across multiple litters in the 0, 5, 20, and 60 mg/kg dose groups, respectively (Table 3). The number of VSDs increased respective to dose between the 5 and 20 mg/kg dose groups, but not between the 20 and 60 mg/kg dose groups due to fewer live fetuses in the 60 mg/kg dose group. Several other visceral and skeletal abnormalities were noted in two and four fetuses in the 5 and 20 mg/kg dose groups and in one fetus in the 60 mg/kg dose group that were also diagnosed with VSD; however, there were no other fetal malformations observed in the remainder of the fetuses with VSDs. Given that the incidences occurred in multiple litters per group, were dose-dependent (5 and 20 mg/kg) or accompanied by marked embryo-fetal lethality (60 mg/kg), the VSDs were considered to be related to vinpocetine exposure. Other spurious findings were also observed in the heart, summarized in Table 3, and were not considered exposure-related due to a high background incidence in the controls and/or the lack of a dose-response in the animals available for evaluation

Table 3.

Rat visceral findings

| Dose (mg/kg)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 20 | 60 | |

| Number fetuses (litters) examined | 293 (21) | 239 (19) | 261 (21) | 51 (8) |

| Heart | ||||

| Misshapen aortic valve [M] | 19 (12)**a | 14 (11) | 17 (10) | 0 (0)** |

| Large right atrium [M] | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Bilateral ventricular septum defect [M] | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 8 (7)** | 2 (2) |

| Thick left ventricle wall [M] | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Major Vessels | ||||

| Supernumerary right carotid artery [M] | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Patent ductus arteriosus [V] | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Absent innominate artery [V] | 4 (4) | 7 (6) | 8 (5) | 1 (1) |

| Short innominate artery [V] | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

Statistically significant (P≤0.01) analysis of litters performed by Cochran-Armitage (trend; denoted in vehicle control column) and Fisher exact (pairwise; denoted in dosed group column) tests.

Statistical analysis of fetuses performed by mixed effects logistic regression models with litter-based adjustments found no statistically significant trend or pairwise comparison.

Data presented as number of fetuses affected (number of litters affected)

[M] = Malformation; [V] = Variation.

Table 4.

Rat skeletal findings

| Dose (mg/kg)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 20 | 60 | |

| Number fetuses (litters) examined | 293 (21) | 239 (19) | 260 (21) | 47 (7) |

| Vertebrae | ||||

| Misshapen cervical arch [M] | 0 (0)a | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Misshapen thoracic arch [M] | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Hemicentric thoracic centrum [V] | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Thoracic centrum incomplete ossification, total [V] | 1## (1)** | 1 (1) | 6# (5) | 8## (3)* |

| Fused lumbar arch [M] | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Fused lumbar centrum [M] | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Lumbar centrum incomplete ossification [V] | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Greater than 26 pre-sacral vertebrae [V] | 0 (0)** | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) |

| Misshapen sacral centrum [M] | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Supernumerary Ribs | ||||

| Full Thoracolumbar, Right [M] | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Full Thoracolumbar, Left [M] | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Full Thoracolumbar, Bilateral [M] | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 9 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Full Thoracolumbar, Total [M] | 1## (1)* | 5 (3) | 12 (4) | 12## (3)* |

| Short Thoracolumbar, Right [V] | 2 (2) | 11# (6) | 16## (12)** | 2# (2) |

| Short Thoracolumbar, Left [V] | 21# (13) | 10 (6) | 22 (13) | 7 (5) |

| Short Thoracolumbar, Bilateral [V] | 6 (4) | 9 (5) | 17# (11)* | 1 (1) |

| Short Thoracolumbar, Total [M] | 29# (14) | 30 (10) | 55# (17) | 10# (5) |

Statistically significant (P≤0.05) analysis of litters performed by Cochran-Armitage (trend; denoted in vehicle control column) and Fisher exact (pairwise; denoted is dosed group column) tests;

(P≤0.01).

Statistically significant (P≤0.05) analysis of fetuses by mixed effects logistic regression models with litter-based adjustments. A significant trend test is indicated in the vehicle control column. A significant pairwise comparison with the vehicle control group is indicated in the dosed group column.

(P≤0.01).

Data presented as number of fetuses affected (number of litters affected)

[M] = Malformation; [V] = Variation.

In the fetal vertebrae, there were increased incidences of incomplete ossification throughout the thoracic centra that were considered exposure-related due to a dose-dependent increase in the 20 and 60 mg/kg exposure groups (Table 4). All of the other malformations and variations present in the vertebrae were limited to three fetuses or were only present as singular incidences, and as such were not considered exposure-related.

An exposure-related effect was observed with increased incidences of full (malformation) and short (variation) supernumerary thoracolumbar ribs (Table 4). There were dose-dependent increases in the incidences of fetuses from multiple litters with full supernumerary thoracolumbar ribs on the left (0%, 0.4%, 0.8%, and 6.4%), right (0%, 0.8%, 0.4%, and 2.1%), and bilateral (0%, 0.8%, 3.5%, and 17%) in the 0, 5, 20, and 60 mg/kg dose groups, respectively, which culminated in total incidences of full thoracolumbar ribs in 0.3%, 2.1%, 4.6%, and 25.5% of the fetuses. Though increased incidences of short supernumerary thoracolumbar ribs are a common background lesion, they do increase in a dose-dependent manner with vinpocetine exposure.

3.2 Rabbit dose-range finding study

Clinical observations were noted in one animal each from the 0, 150, and 300 mg/kg dose groups and were limited to red abnormal vaginal discharge occurring on GD 22-25, 21-25, and 20-28, respectively (data available online; NTP, 2017). The doe with red abnormal vaginal discharge from the 150 mg/kg dose group was removed from study on GD 25 due to abortion. At necropsy, abortion was confirmed for the doe in the 150 mg/kg dose group and post-implantation loss was noted in the doe from the 300 mg/kg dose group. No additional findings were noted in the doe from the control group.

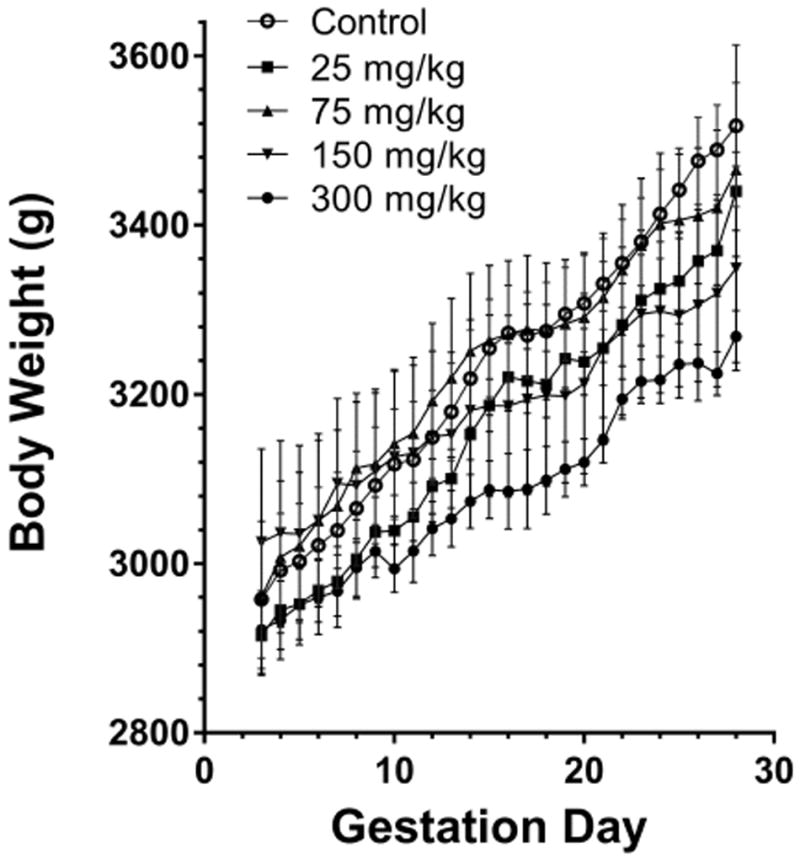

Body weight and food consumption data are displayed in (Table 5 and Figure 2). Transient increases and decreases in maternal body weight gains were observed across all dose groups, with does in the 150 and 300 mg/kg dose groups displaying lower body weight gains throughout gestation (44% and 34%, respectively, relative to control). The decreased maternal body weight gains in the 150 and 300 mg/kg dose groups were consistent with decreased food consumption in these groups. The decreases in food consumption in these dose groups were transient across several dosing intervals (11% to 30%, in the 150 and 300 mg/kg groups compared to controls) and culminated in overall decreases of 26% and 17%, respectively, from GD 7 to 29.

Table 5.

Doe body weight gain and food consumption

| Dose (mg/kg)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25 | 75 | 150 | 300 | |

| Number of Pregnant Does | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| Body Weight Gaina | |||||

| GD 7 - 29 | 460.2 ± 33.8**b | 458.2 ± 46.2 | 399.3 ± 58.4 | 256.7 ± 40.9** | 304.1 ± 33.2** |

| GD 29 Bodyweight (g)b | 3499.4 ± 64.6* | 3406.5 ± 58.0 | 3467.7 ± 95.0 | 3358.4 ± 105.6 | 3271.4 ± 34.2 |

| Gravid Uterine Weight (g)b | 515.3 ± 14.7** | 470.1 ± 20.7 | 483.9 ± 32.2 | 421.9 ± 39.3* | 340.9 ± 27.7** |

| Food Consumption (g)a | |||||

| GD 7 - 29 | 137.6 ± 4.3** | 131.8 ± 5.7 | 125.2 ± 4.0 | 101.3 ± 11.4** | 113.8 ± 8.9** |

Data are displayed as mean ± standard error and do not include non-pregnant animals. The 150 mg/kg group had one doe that aborted early on GD 25, this animal was included in bodyweight calculations until removal from study on day of abortion.

(g) = grams; GD = Gestation Day.

Statistically significant (P≤0.05) trend (denoted in vehicle control column) or pairwise comparison (denoted is dosed group column);

(P≤0.01).

Statistical analysis performed by Jonckheere’s test (trend) and Williams’ or Dunnett’s test (pairwise). Body weight gains and food consumption for pregnant animals are given in grams/day and grams/animal/day, respectively.

Statistical analysis performed using the random effects model (trend and pairwise).

Figure 2.

Rabbit maternal body weight throughout gestation.

There was no difference in the number of pregnant female rabbits, the mean number of corpora lutea, and implantation sites across groups (Table 6). There was an exposure-related effect on embryo-fetal survival in the 300 mg/kg dose group. Uterine examination revealed fewer live fetuses per litter in the 300 mg/kg dose group (mean number of live fetuses per litter was 6.5 compared to 9.1 in the controls and the total number of fetuses for evaluation was 52 as compared to 73 in controls). Overall, these findings in the 300 mg/kg dose group can be explained by an increase in percent post-implantation loss (20.4% compared to 1.4% in controls). These findings in the 300 mg/kg dose group were also associated with a 34% reduction in mean gravid uterine weights as compared to controls. There was no exposure-related effect on embryo-fetal survival in any of the dose groups of 150 mg/kg or less; however, lower gravid uterine weights and fewer viable fetuses were noted in the 150 mg/kg group, which is likely a result of the higher percent pre-implantation loss in this group and not exposure-related.

Table 6.

Doe Cesarean section observations and fetal weights

| Dose (mg/kg)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25 | 75 | 150 | 300 | |

| Number of Pregnant Does | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| Corpora luteaa | 9.50 ± 0.38 | 8.71 ± 0.47 | 9.63 ± 0.53 | 8.86 ± 0.40 | 9.13 ± 0.61 |

| Implantation sitesa | 9.25 ± 0.41 | 8.00 ± 0.44 | 9.25 ± 0.56 | 7.71 ± 0.68 | 8.38 ± 0.56 |

| Pre-implantation loss (%)a | 2.70 ± 1.80 | 7.78 ± 3.15 | 3.82 ± 2.82 | 13.02 ± 6.79 | 7.08 ± 5.13 |

| Early resorptionsb | 0.13 ± 0.13* | 0 | 0 | 0.14 ± 0.14 | 1.63 ± 0.71 |

| Late resorptionsb | 0 | 0.14 ± 0.14 | 0.25 ± 0.16 | 0 | 0.25 ± 0.25 |

| Whole litter resorptionsc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Post-implantation loss (%)a | 1.39 ± 1.39 | 3.37 ± 2.18 | 2.53 ± 1.66 | 3.57 ± 3.57 | 20.42 ± 9.05 |

| Viable fetuses | 73 | 54 | 72 | 53 | 52 |

| Live fetuses/littera | 9.1 ± 0.4* | 7.7 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | 7.6 ± 0.8 | 6.5 ± 0.7* |

| Sex ratio (% male)a | 36.3 | 50.7 | 52.7 | 45.2 | 50.8 |

| Fetal weight (g)b | 39.72 ± 1.33** | 41.47 ± 0.95 | 37.53 ± 0.90 | 39.36 ± 1.74 | 35.78 ± 1.15 |

| Adjusted fetal weight (g)d | 40.27 ± 0.53** | 40.60 ± 0.56 | 38.39 ± 0.62* | 38.25 ± 0.59* | 33.64 ± 0.63** |

Data are displayed as mean ± standard error and do not include non-pregnant animals (n = 8 presumed pregnant dams were assigned per group).

(g) = grams.

Statistically significant (P≤0.05) trend (denoted in vehicle control column) or pairwise comparison (denoted in dosed group column);

(P≤0.01).

Statistical analysis performed by Jonckheere’s test (trend) and Shirley’s or Dunn’s (pairwise).

Statistical analysis performed using the random effects model (trend and pairwise).

Statistical analysis performed by Cochran-Armitage (trend) and Fisher exact (pairwise) tests.

Litter weights adjusted for litter size. Statistical analysis performed by Jonckheere’s test (trend) and Williams’ or Dunnett’s (pairwise) tests.

There was a significantly decreased trend in mean fetal body weight per litter and adjusted fetal weight per litter (Table 6). There were exposure-related decreases in adjusted mean fetal weights per litter in the 75, 150 and 300 mg/kg dose groups, with mean fetal weights 4.7, 5, and 16.5% lower than controls, respectively. There were no external malformations or variations in the rabbit fetuses attributable to vinpocetine exposure; internal and skeletal exams were not performed in rabbits (NTP 2017).

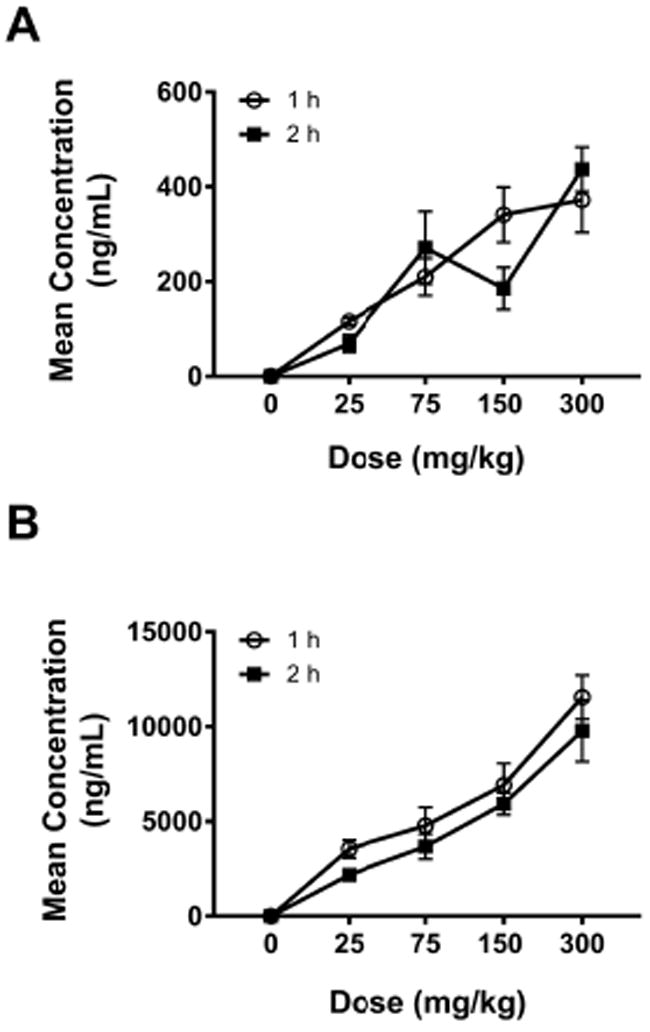

3.3 Vinpocetine and Apovincaminic Acid in Rabbit Plasma

Vinpocetine and AVA were detected at both timepoints in the doe plasma. The mean plasma concentrations (ng/mL) at 1 and 2 h following vinpocetine administration on GD 19 are presented in Figures 3A and 3B for vinpocetine and AVA, respectively. In general, the plasma concentration of vinpocetine increased less than proportionally to the dose and concentrations were similar at 1 and 2 h timepoints, with the exception of the 150 mg/kg dose group (Figure 3A). Vinpocetine was rapidly and highly metabolized to AVA in rabbits; the plasma concentration of AVA was higher at 1 h compared to 2 h (Figure 3B) and AVA concentration was 20 to 30-fold higher at 1 h than the vinpocetine concentration in the dose groups investigated. Similar to vinpocetine, plasma concentration of AVA increased less than proportionally to the dose.

Figure 3.

Mean concentration of vinpocetine (A) and apovincaminic acid (B) in pregnant rabbit plasma 1 and 2 hrs following oral vinpocetine administration.

4.0 Discussion

In the present studies with rats, vinpocetine was well tolerated by the dams and all the observed maternal findings (decreased maternal body weights and body weight gains, decreased food consumption, increased incidences of abnormal vaginal discharge) resulting from administration of 60 mg/kg were consistent with the significant embryo-fetal loss that occurred in this dose group. As a result, only a limited number of fetuses were available in the high dose group for complete fetal evaluations. Embryo-fetal death is often accompanied by growth retardation and malformations, which has led to postulation that their close association indicates that they are different endpoints on a spectrum of the embryo’s response to a toxicant (Wilson, 1965; Clark, 2004). Illustrative of this point, there was dose-dependent evidence of both growth retardation (decreased fetal weights, delayed ossification) and teratogenicity (ventricular septum defects; VSDs, supernumerary thoracolumbar ribs) in the rat fetuses of vinpocetine-exposed dams in the present studies, despite the lower number of fetuses in the high dose group. Subsequent studies performed in rabbits to evaluate whether these findings could be repeated in a second species resulted in similar effects on maternal observations indicative of the embryo-fetal loss and decreased fetal weights that were observed.

Of the few studies in the literature that evaluated the developmental effects of vinpocetine in rats, decreased maternal body weight gain (50 mg/kg) and uterine bleeding (50 and 150 mg/kg) has also been demonstrated in conjunction with high fetal mortality (150 mg/kg) and complete litter resorptions (55% of the dams administered 135 mg/kg) (Cholnoky and Dömök, 1976). Similarly, a single study on the effects of vinpocetine administration during gestation in rabbits, summarized in the same paper, also found a small significant reduction in body weight gain in their high dose group (orally administered, 18 mg/kg) with no other maternal toxicity noted (Cholnoky and Dömök, 1976).

VSDs were observed at low incidence in fetuses from multiple litters in all vinpocetine-exposed groups of rats. VSDs are a malformation that arise as a result of a disruption in the developmental processes that lead to partitioning of the ventricles and manifests as an opening in the interventricular septum (IVS). Development of the IVS is typically complete by GD 15 in rats, and consists of both muscular and membranous segments (DeSesso, 1997). VSDs can occur spontaneously, have been identified as the most common type of congenital heart disease in humans, and have been shown to close during postnatal development in both rats and humans (Hoffman and Kaplan, 2002; Solomon, 1997; Roguin, 1995; Du, 1998; Paladini, 2000). Membranous VSDs can also be induced in rats as a result of toxicant exposure (Solomon, 1997, Fleeman, 2004). Administration of trimethadione on GD 9 and 10, results in a high incidence of membranous VSDs that are morphologically similar to spontaneously occurring VSDs, albeit larger in size (Solomon, 1997; Fleeman, 2004). These toxicant induced small membranous VSDs in rats have also been shown to close postnatally, indicative of a potential delay in cardiac development (Solomon, 1997; Fleeman, 2004). The increased incidence in VSDs seen in the current studies with vinpocetine exposure, could be indicative of a developmental delay since a decrease in fetal weight was also observed in the 60 mg/kg group and there were delays in ossification. However, it should be noted that fetal weight (unadjusted) was not affected at 5 and 20 mg/kg, where increased incidences of VSDs also occurred. Additionally, Fleeman et al. (2004) found no association between the occurrence of VSDs and decreased fetal weight, suggesting that VSDs are independent of overall fetal growth as measured by fetal weight. Therefore, the increased incidences of VSDs in the rat fetuses from this study are likely related to the administration of vinpocetine.

The formation of supernumerary ribs (SNR) in the thoracolumbar region are indicative of an alteration in early embryonic development of the axial skeleton (Branch, 1996). The formation of full SNRs are a consistent finding resulting from exposure to a wide range of dissimilar chemicals in a dose-dependent manner, including sodium salycilate (Foulon, 1999), bromoxynil phenol or bromoxynil octanoate (Rogers, 1991), and valproic acid (Narotsky, 1994). Additionally, increased incidences of SNRs have previously been associated with maternal stress, although this effect appears to be species specific as it has been demonstrated mainly in mice (Chernoff, 1987; Beyer and Chernoff, 1986). Aside from the maternal effects associated with significant embryo-fetal loss, the doses of vinpocetine administered in the current studies did not result in maternal stress or toxicity, indicating that the increased incidences of full SNRs in fetuses from multiple litters in the current studies are likely related to vinpocetine exposure.

As incidences of full SNRs are indicators of developmental changes in axial skeleton development, they are generally not isolated events. Their formation has been significantly correlated with other findings in mice, such as the presence of an additional pre-sacral vertebra (Chernoff and Rogers, 2010). An increase in the incidences of greater than 26 pre-sacral vertebrae was seen in the current studies in fetuses from dams exposed to 60 mg/kg vinpocetine. All of the fetuses with this variation also had incidences of full SNRs (bilateral or on the left only). Incidences of short SNRs, or rudimentary ribs, were significantly increased in the fetuses of dams exposed to 20 and 60 mg/kg vinpocetine. However, these increased incidences of short SNRs may or may not have biological significance as they are a common background variation in this strain of rat and their presence is transient and has been shown to diminish during the post-natal period in rats (Chernoff, 1991; Wickramaratne, 1988; Foulon, 2000). In contrast, full SNRs have been shown to persist from birth into adulthood, as demonstrated by Foulon et al. (2000) who examined salicylate-induced full SNRs over time through radiography. Incidences of full SNRs in the lumbar region have also been reported in humans, where they have been associated with adverse outcomes such as pain in the lumbar region and increased incidences of L4 and L5 degeneration (Chernoff and Rogers, 2010).

Developmental toxicity, in the form of fetal growth retardation, was evidenced by significant increases in the percentage of fetuses with incomplete ossification throughout the thoracic centra and decreased fetal weights. The thoracic centrum is the body of the thoracic vertebrae and is routinely ossified before birth. Aside from fetal weight, the degree of ossification of the main components of the axial skeleton and the extremities in the fetus are typical indicators of developmental status (Kehra, 1981). Cyclophosphamide is an example of another toxicant where exposure in the mouse and rat resulted in fetal resorptions, as well as growth retardation, delayed ossification, and skeletal malformations (Ujhazy, 1979; Matalon, 2004; Jeyaseelan and Singh, 1984). Maternal stress and malnutrition, especially during the period of rapid fetal growth late in gestation, can also result in reduced fetal weight and incomplete skeletal ossification. However, the reduced maternal body weights and food consumption seen in this study were a result of fetal loss and not maternal toxicity. Additionally, there were significant reductions in mean fetal weight per litter and adjusted fetal weights per litter in the rabbits. Though the fetal rabbit examinations were limited to external exams, the replication of the reduction in fetal weight in a second non-rodent species, provides further support of the findings in the rat that indicate a developmental delay resulting from vinpocetine exposure during gestation.

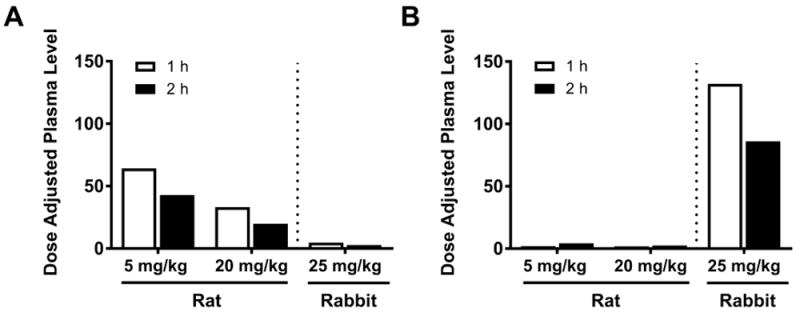

The developmental toxicity of vinpocetine was notable in that the main findings (embryo-fetal lethality and decreased fetal weights), occurred in two species in the absence of maternal toxicity. However, in contrast to the rats, there appears to be a species-specific difference in response as the increase in post-implantation loss in the rabbits was limited to the 300 mg/kg group, the magnitude of the response was diminished (20% in the rabbit 300 mg/kg group vs. 83% in the rat 60 mg/kg group) and was not significantly increased compared to the controls. We have previously demonstrated significant fetal transfer of vinpocetine following repeat administration of vinpocetine (5 and 20 mg/kg) in pregnant rats from GD 6 to 18, with fetal Cmax and AUC values ≥ 55% of dams (Waidyanatha et al., 2017). Additionally, this study identified the rapid metabolism of vinpocetine to its main metabolite, AVA, in the dam, with AVA levels ≥ 2.7-fold higher than vinpocetine. However, AVA levels in the fetus were much lower than vinpocetine. The dose-normalized plasma levels of vinpocetine and AVA in rabbits in the present study at 1 and 2 h following administration of 25 mg/kg vinpocetine on GD 19 was compared with the corresponding data from the rat study (Waidyanatha et al., 2017) (Figure 4). The dose-normalized vinpocetine levels were 7- to 15-fold higher in the rats compared to the rabbits (Figure 4A). In contrast, the dose-normalized levels of AVA in rabbits were 19- to 75- fold higher than rats (Figure 4B). Taken collectively, these data explain the observed species difference in fetal toxicity, where rats were more sensitive than the rabbits, indicating that vinpocetine is more relevant to toxicity than AVA.

Figure 4.

Comparison of dose-normalized plasma concentrations of vinpocetine (A) and apovincaminic acid (B) in pregnant ratsa and rabbits at 1 and 2 hrs following oral vinpocetine administration. aPregnant rat plasma samples were processed and analyzed as detailed in previously published toxicokinetics studies of vinpocetine and apovincaminic acid (Waidyanatha, 2017). The present previously published data for the rat are being presented here for direct comparison purposes to the presently reported rabbit data.

The suggested doses recommended by the Physicians’ Desk Reference for Nutritional Supplements and the doses that are suggested on available product labels range from 5 to 90 mg/day (Hendler and Rorvik, 2001). Published human systemic exposure data are limited, but have shown a Cmax of 25.2 and 64.3 ng/mL and an AUC of 249.4 and 519.7 ng*h/mL following a single dose of 10 mg (Elbary, 2002; Karshoum, 2013). A comparison of systemic exposure where VSDs were noted in rats (5 mg/kg) to that at suggested doses in humans (single 10 mg dose), results in exposure multiples of ≤14 and ≤9 for Cmax and AUC, respectively (Waidyanatha, 2017). These dose comparisons suggest that exposure to vinpocetine in rats following a repeated 5 mg/kg dose is similar to that following a single 10 mg dose in humans.

In summary, as a result of the adverse effects on embryo-fetal development, demonstrated in both the rat and rabbit, combined with low exposure multiples between the rat and human, there is concern for exposure to vinpocetine during pregnancy in humans.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Georgia Roberts and Kristen Ryan for their review of this manuscript. This work was performed for the National Toxicology Program, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract Nos. HHSN273201300010C and HHSN273201400027C, by Southern Research Institute and Battelle. The authors would like to thank the chemists at Battelle who performed the chemistry analyses included in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Anonymous. Cavinton, injection, tablet. Geor Med. 1984;14:363–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage P. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. New York (NY): John Wiley and Sons; 1971. pp. 362–365. [Google Scholar]

- Avula B, Chittiboyina AG, Sagi S, Wang YH, Wang M, Khan IA, Cohen PA. Identification and quantification of vinpocetine and picamilon in dietary supplements sold in the United States. Drug Test Anal. 2015;8:334–343. doi: 10.1002/dta.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereczki D, Fekete I. Vinpocetine for acute ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000480.pub2. CD000580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer PE, Chernoff N. The induction of supernumerary ribs in rodents: role of maternal stress. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 1986;6:419–429. doi: 10.1002/tcm.1770060508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch S, Rogers JM, Brownie CF, Chernoff N. Supernumerary lumbar rib: manifestation of basic alteration in embryonic development of ribs. J Applied Toxicol. 1996;16(2):115–119. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1263(199603)16:2<115::AID-JAT309>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholnoky E, Dömök LI. Summary of safety tests of ethyl apovincaminate. Arzneim-Forsch (Drug Res) 1976;26(10a):1938–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff N, Kavlock RJ, Beyer PE, Miller D. The potential relationship of maternal toxicity, general stress, and fetal outcome. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 1987;7:241–253. doi: 10.1002/tcm.1770070306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff N, Rogers JM. Supernumerary ribs in developmental toxicity bioassays and in human populations: incidence and biological significance. J Toxicol Environ Health, Part B. 2010;7(6):437–449. doi: 10.1080/10937400490512447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff N, Rogers JM, Turner CI, Francis BM. Significance of supernumerary ribs in rodent developmental toxicity studies: postnatal persistence in rats and mice. Fundam Applied Toxicol. 1991;17:448–453. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(91)90196-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RL, White TEK, Clode SA, Gaunt I, Winstanley P, Ward SA. Developmental toxicity of artesunate and an artenusate combination combination in the rat and rabbit. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2004;71:380–394. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSesso JM. Comparative Embryology. In: Hood RD, editor. Handbook of Developmental Toxicology. CRC Press, Inc; 1997. pp. 111–174. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WJ, Massey FJ. Introduction to Statistical Analysis. 2. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill Book Company, Inc; 1957. pp. 276–278, 412. [Google Scholar]

- Du ZD, Roguin N, Wu XJ. Spontaneous closure of muscular ventricular septal defect identified by echocardiography in neonates. Cardiol Young. 1998;8:500–505. doi: 10.1017/s1047951100007174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn OJ. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics. 1964;6:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnett CW. A multiple comparison procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. J Am Stat Assoc. 1955;50:1096–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Elbary AA, Foda N, El-Gazayerly O, ElKhatib M. Reversed phase liquid chromatographic determination of vinpocetine in human plasma and its pharmacokinetic application. Anal Lett. 2002;35:1041–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Feigin VL, Doronin BM, Popova TF, Gribatcheva EV, Tchervov DV. Vinpocetine treatment in acute ischaemic stroke: a pilot single-blind randomized clinical trial. Eur Neurol J. 2001;8:81–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleeman TL, Cappon GD, Hurtt ME. Postnatal closure of membranous ventricular septal defects in Sprague-Dawley rat pups after maternal exposure with trimethadone. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2004;71:185–190. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulon O, Jaussely C, Repetto M, Urtizberea M, Blacker AM. Postnatal evolution of supernumerary ribs in rats after a single administration of sodium salicylate. J Appl Toxicol. 2000;20:205–209. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(200005/06)20:3<205::aid-jat635>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gart JJ, Chu KC, Tarone RE. Statistical issues in interpretation of chronic bioassay tests for carcinogenicity. JNCI. 1979;62:957–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendler S, Rorvik D. Vinpocetine. In: Hendler S, Rorvik D, editors. Physicians Desk Reference for Nutritional Supplements. 1. New Jersey: Thompson Healthcare, Medical Economics Co., Inc; 2001. pp. 460–462. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JIE, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(12):1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan N, Singh S. Forelimb malformation in rats caused by cyclophosphamide. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55(6):643–646. doi: 10.3109/17453678408992414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonckheere AR. A distribution-free k-sample test against ordered alternatives. Biometrika. 1954;41:133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kehra KS. Common fetal aberrations and their teratologic significance: a review. Fund Appl Toxicol. 1981;1:13–18. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/1.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharshoum RM, Sanad RA, Abdelhaleem Ali AM. Comparative pharmacokinetic study of two lyophilized orally disintegrating tablets formulations of vinpocetine in human volunteers. Int J Drug Deliv. 2013;5(2):167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CA, Trammell C. A rapid procedure for routine double staining of cartilage and bone in fetal and adult animals. Stain Technol. 1981;56(5):271–3. doi: 10.3109/10520298109067325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Lingsma HF, Steyerberg EW, Lesaffre E. Logistic random effects regression models: a comparison of statistical packages for binary and ordinal outcomes. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley BM. A Health Learning Handbook. Minnesota: BL Publications; 2000. Vinpocetine : Revitalize your brain with periwinkle extract! p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Maconi E, Binaghi F, Pitzus F. A double-blind clinical trial of vinpocetine in the treatment of cerebral insufficiency of vascular and degenerative origin. Curr Ther Res. 1986;40(4):702–709. [Google Scholar]

- Makris SL, Solomon HM, Clark R, Shiota K, Barbellion S, Buschmann J, Ema M, Fujiwara M, Grote K, Hazelden KP, Hew KW, Horimoto M, Ooshima Y, Parkinson M, Wise LD. Terminology of developmental abnormalities in common laboratory animals (Version 2) Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2009;86:227–327. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matalon ST, Ornoy A, Lishner M. Review of the potential effects of three commonly used antineoplastic and immunosuppressive drugs (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, doxorubicin, on the embryo and placenta) Repro Toxicol. 2004;18:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narotsky MG, Francis EZ, Kavlock RJ. Developmental toxicity and structure-activity relationships of aliphatic acids, including dose-response assessment of valproic acid in mice and rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1994;22:251–265. doi: 10.1006/faat.1994.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie S, Fan X, Peng Y, Yang X, Wang C, Pan W. In vitro and in vivo studies on the complexes of vinpocetine with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. Arch Pharm Res. 2006;30(8):991–1001. doi: 10.1007/BF02993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [NTP] National Toxicology Program. [November 15, 2017];DART-03: Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity Report Tables & Curves. https://tools.niehs.nih.gov/cebs3/views/?action=main.dataReview&bin_id=2687.

- Paladini D, Palmieri S, Lamberti A, Teodoro A, Martinelli P, Nappi C. Characterization and natural history of ventricular septal defects in the fetus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:118–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pálosi E, Szporny L. Effects of ethyl apovincaminate on the central nervous system. Arzneim-Forsch (Drug Res) 1976;26(10a):1926–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendergast JF, Gange SJ, Lindstrom MJ. Correlated Binary Data. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. 2005;2 [Google Scholar]

- Peruzza M, DeJacobis M. A double-blind placebo controlled evaluation of the efficacy and safety of vinpocetine in the treatment of patients with chronic vascular or degenerative senile cerebral dysfunction. Avd Therapy. 1986;3(4):201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro LSS, Falcão AC, Patrício JAB, Ferreira DC, Veiga FJB. Cyclodextrin multicomponent complexation and controlled release delivery strategies to optimize the oral bioavailability of vinpocetine. J Pharm Sci. 2004;96(8):2018–2028. doi: 10.1002/jps.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JM, Francis BM, Barbee BD, Chernoff N. Developmental toxicity of bromoxynil in mice and rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1991;17:442–447. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(91)90195-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roguin N, Du ZD, Barak M, Nasser N, Hershkowitz S, Milgram E. High prevalence of muscular ventricular septal defect in neonates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26(6):1545–1548. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00358-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley E. A non-parametric equivalent of Williams’ test for contrasting increasing dose levels of treatment. Biometrics. 1977;33:386–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitges M, Aldana BI, Reed RC. Effect of the anti-depressant sertraline, the novel anti-seizure drug vinpocetine and several conventional antiepileptic drugs on the epileptiform EEG activity induced by 4-aminopyridine. Neurochem Res. 2016;41:1365–1374. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-1840-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon HM, Wier PJ, Fish CJ, Hart TK, Johnson CM, Posobiec LM, Gowan CC, Maleeff BE, Kerns WD. Spontaneous and induced alterations in the cardiac membranous ventricular septum of fetal, weanling, and adult rats. Teratology. 1997;55:185–194. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199703)55:3<185::AID-TERA3>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sozanski T, Magdalan J, Trocha M, Szumny A, Merwid-Lad A, Slupski W, Karazniewicz-Lada M, Kielbowicz G, Ksiadzyna D, Szelag A. Omeprazole does not change the oral bioavailability or pharmacokinetics of vinpocetine in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63(5):1258–1263. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples RE. Detection of visceral alterations in mammalian fetuses. Teratology. 1974;9(3):A37–A38. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckhardt JL, Poppe SM. Fresh visceral examination of rat and rabbit fetuses used in teratogenicity testing. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 1984;4(2):181–188. doi: 10.1002/tcm.1770040203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmári S, Whitehouse P. Vinpocetine for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003119. Art. No.: CD003119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taiji H, Kanzaki J. Clinical study of vinpocetine in the treatment of vertigo. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 1986;14(2):577–589. [Google Scholar]

- Thal LJ, Salmon DP, Lasker B, Bower D, Klauber MR. The safety and lack of efficacy of vinpocetine in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:515–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb05682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne Research, Inc. Monograph: vinpocetine. Altern Med Rev. 2002;7(3):240–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truss MC, Stief CG, Ückert S, Becker AJ, Schultheiss D, Machtens S, Jonas U. Initial clinical experience with the selective phosphodiesterase-I isoenzyme inhibitor vinpocetine in the treatment of urge incontinence and low compliance bladder. World J Urol. 2000;18:439–443. doi: 10.1007/pl00007088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujhazy E, Preinerova M, Jozefik M. Effects of cyclophosphamide on the prenatal development of the Swiss strain mice. Neoplasma. 1979;26(5):529–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereczkey L, Szentirmay Z, Szporny L. Kinetic metabolism of vinpocetine in the rat. Arzneim-Forsch (Drug Res) 1979b;29(6):953–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waidyanatha S, Troy H, South N, Gibbs S, Mutlu E, Burback B, McIntyre BS, Catlin N. Systemic exposure of vinpocetine in pregnant Sprague Dawley rats following repeated oral exposure: an investigation of fetal transfer. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2017. 2017 Nov 15; doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.11.011. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramaratne GAS. The post-natal fate of supernumerary ribs in rat teratogenicity studies. J Appl Toxicol. 1988;8(2):91–94. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550080205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA. A test for differences between treatment means when several dose levels are compared with a zero dose control. Biometrics. 1971;27:103–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA. The comparison of several dose levels with a zero dose control. Biometrics. 1972;28:519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA. A note on Shirley’s nonparametric test for comparing several dose levels with a zero-dose control. Biometrics. 1986;42:183–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JG. Embryological Considerations in teratology. In: Wilson JG, Warkany J, editors. Teratology: Principles and Techniques. Chicago, IL: Univ of Chicago Pr; 1965. pp. 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia HM, Su LN, Guo JW, Liu GM, Pang ZQ, Jiang XG, Chen J. Determination of vinpocetine and its primary metabolite, apovincaminic acid, in rat plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2010;878(22):1959–1966. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, He L, Nie S, Guan J, Zhang X, Yang X, Pan W. Optimized preparation of vinpocetine proliposomes by a novel method and in vivo evaluation of its pharmacokinetics in New Zealand rabbits. J Control Release. 2009;140:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla EP. Multiparous species present problems (and possibilities) to developmentalists. Dev Psychobiol. 1997;30:141–150. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199703)30:2<141::aid-dev5>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]