Abstract

This analysis examined type 2 diabetes (T2D) as a predictor of colorectal cancer (CRC) survival within the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Registry linkages in Hawaii and California identified 5,284 incident CRC cases. After exclusion of cases with pre-existing cancer, diagnosis within 1 year, and systemic disease, the analytic dataset had 3,913 cases with 1,800 all-cause and 678 CRC-specific deaths after a mean follow-up of 9.3±5.2 years. Among CRC cases, 707 were diagnosed with T2D 8.9±5.3 years before CRC. Cox regression with age as time metric was applied to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for T2D status as predictor of CRC-specific and all-cause survival while adjusting for known confounders. Overall, CRC-specific survival was not associated with pre-existing T2D (HR=0.84; 95% CI=0.67–1.07). However, a significant interaction was seen for comorbidity (pinteraction=0.03) with better survival among those without pre-existing conditions (HR=0.49; 95% CI=0.25–0.96) while no association was seen in patients with comorbid conditions. All-cause mortality was also not related to pre-existing T2D (HR=1.11; 95% CI=0.98–1.27), but significantly elevated for individuals with T2D reporting comorbid conditions (HR=1.36; 95% CI=1.19–1.56). Stratification by T2D duration suggested higher CRC-specific and all-cause mortality among participants with a T2D history of ≥10 than <10 years. The findings were consistent across sex and ethnic subgroups. In contrast to previous reports, pre-existing T2D had no influence on disease-specific and all-cause survival among CRC patients. Only participants with additional comorbidity and possibly those with long T2D duration experienced higher mortality related to T2D.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Type 2 diabetes, Ethnicity, Cohort, Survival, Administrative data

Introduction

As the aging of the population continues worldwide, the number of people living with two chronic diseases, such as colorectal cancer (CRC) and type 2 diabetes (T2D), is increasing.1 CRC is the 4th most commonly diagnosed malignancy in the U.S. with an estimate of about 135,000 new cases and 50,000 deaths per year.2 At the same time, the epidemic of T2D is expected to grow to 642 million people worldwide by 2040.3 The two chronic diseases have many risk factors in common including older age, low quality diet, obesity, physical inactivity and smoking.4 There is evidence that a T2D diagnosis may be associated with an increased cancer risk and worse prognosis.5 For example, T2D is associated with an approximately 30% higher risk to develop CRC in some populations.6–8

As to the influence of T2D on survival among CRC patients, findings are inconsistent and the number of reports is relatively small. A T2D diagnosis was associated with higher CRC-related mortality in five studies,1,9–12 but several investigations reported no significant association13–15 or a higher mortality from cardiovascular disease only.16 Many predictors of survival among CRC patients have been identified; these may assist patients and healthcare personnel in decision making and disease management.12 However, few previous studies have looked at the influence of T2D status in different ethnic groups. Given the high T2D incidence in many non-white populations17 and the elevated CRC incidence in Japanese and African Americans18, it is of interest to identify ethnic-specific differences in the association to understand differences in prognosis. The current study investigates the hypothesis that a diagnosis of T2D shortens survival among white, African American, Japanese American, Native Hawaiian, and Latino participants of the Multiethnic Cohort (MEC) with CRC.

Methods

Study Population

In 1993–1996, the MEC recruited more than 215,000 men and women between ages 45–75 years from Hawaii and Los Angeles County19 to prospectively study the association of lifestyle and genetic factors with cancer and other chronic diseases among an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse population. The self-reported ethnicity distribution in the MEC is as follows: African American (16%), Latino (22%), Japanese American (26%), Native Hawaiian (7%), white (23%), and other ancestry (6%). Response rates of the self-administered baseline questionnaire varied between 20% and 49% depending on sex and ethnicity.19

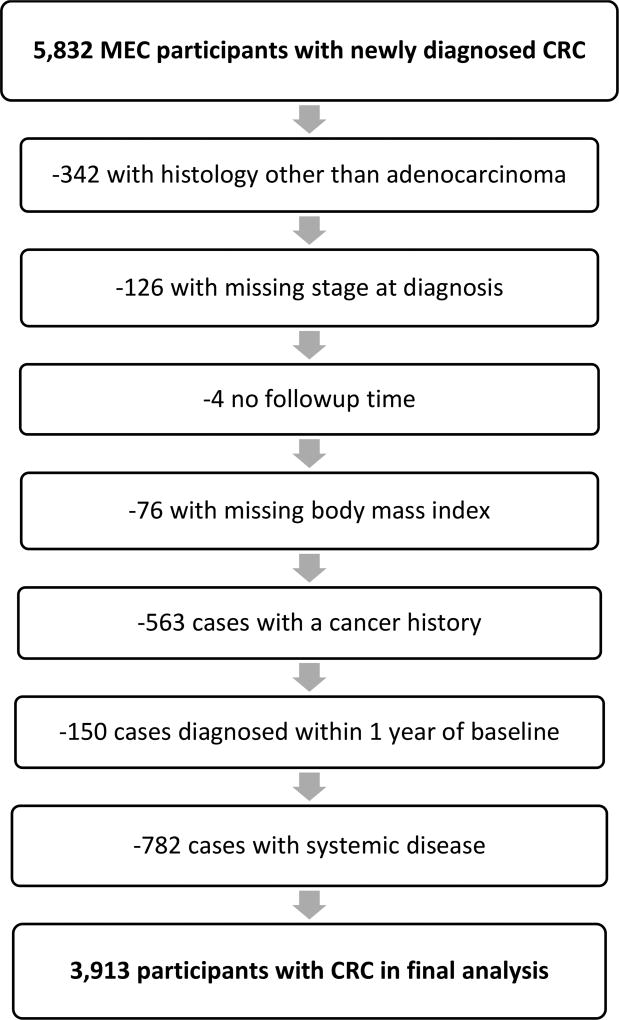

Incident colon and rectal cancer cases were identified through regular linkages with the Los Angeles County Cancer Surveillance Program, the State of California Cancer Registry, and the statewide Hawaii Tumor Registry, all part of the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Dates and causes of death were identified by routine linkages with California and Hawaii vital record and the National Death Index databases. Complete case and/or death ascertainment was available up to December 31, 2013. Among MEC members of the five major ethnic groups who did not have a previous self-reported or registry-identified diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer, 5,832 newly diagnosed invasive CRC cases (ICD9: 153.0–154.8, ICD10:C18–C20) were identified between cohort entry and the end of 2013. After additional exclusions (342 with histology not adenocarcinoma, 126 with missing stage at diagnosis, 4 without follow-up time, 76 with missing body mass index [BMI]), 563 with a history of any previous cancer who may have changed their lifestyle, 150 diagnosed within 1 year of cohort entry, and 763 with metastatic disease), 3,913 cases remained for analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MEC Participants with CRC in the Current Analysis

Questionnaire and Diabetes Data

At baseline, all participants completed a 26-page, self-administered mail questionnaire (QX1) asking for demographic information, a lifetime smoking history, dietary history assessed by a validated food frequency questionnaire20, and physical activity during the last year.19 As partial validation, the association of sleep duration with objective measures of energy balance was demonstrated in a subset of cohort members.21 In 1999–2002, a 4-page follow-up survey (QX2) was returned by 84% of the cohort to update BMI and medical conditions. In 2003–2007, a full questionnaire (QX3) was completed by 50% of the cohort. All three questionnaires included the question: “Has your doctor ever told you that you had diabetes?” On the baseline survey, 25,858 out of the 215,831 (12%) participants self-reported a T2D diagnosis. In QX2 and QX3, this percentage increased to 14% and 18%, respectively. T2D was defined as self-reported T2D in QX1–3 confirmed by administrative data from 3 different sources: Medicare claims,22 a linkage with health plans in Hawaii,23 and hospital discharge diagnosis data in California.24 Considering records from all 3 data sources, 83% of T2D self-reports were confirmed by at least one administrative data source. Participants with unconfirmed self-reports were considered individuals without a T2D diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

We compared participants with and without T2D for major characteristics. To evaluate the association of T2D with overall and CRC-specific mortality, we computed multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using Cox proportional hazards models. To minimize bias due to the inclusion of incident T2D cases after CRC diagnosis (N=39; 5.2%), only T2D cases detected before CRC diagnosis (N=707) were included in the models. With age as the time metric, the follow-up time started at the age at CRC diagnosis and ended at the age of death or the end of follow-up on December 31, 2013. For CRC-specific death analysis, participants who died of other causes were censored at the time of death. All analyses were adjusted for age, ethnicity, education, physical activity (<30 vs. ≥30 minutes of daily moderate/vigorous activity), smoking status, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), family history of CRC, and comorbidity (heart attack or stroke) at cohort entry, and BMI as time-varying variable from QX1 and QX2. The covariate selection was based on previous cancer survival analyses within the MEC.23,25 For covariates with missing values, i.e., physical activity, smoking status, family history of CRC, and comorbidity, a missing category was created. To evaluate T2D duration, the time between first known T2D and CRC diagnosis was divided into <10 and ≥10 years. All analyses were stratified by T2D duration, sex, ethnicity, tumor site, stage of disease, family history of CRC, and comorbidity. Interactions were assessed using a global Wald test of the cross-product terms. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) using two-tailed tests with significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Among 3,913 CRC cases (Table 1), 707 (18.1%) had known T2D before being diagnosed with CRC. The respective mean ages of participants at cohort entry, T2D discovery, CRC diagnosis, and survival (age at death or 12/31/2013) were 62.6, 68.6, 72.5, and 79.7 years, respectively. The mean follow-up time from CRC diagnosis was 9.3±5.2 years. T2D was diagnosed ≥10 years before CRC in 284 participants and <10 years among 423 cohort members. The mean time between T2D detection and CRC diagnosis was 8.9±5.3 years. Pre-existing T2D rates across stage at diagnosis and tumor grade were not substantially different.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Colorectal Cancer Cases, Multiethnic Cohort, 1993–2013

| Characteristic | Category | N | T2D1 N (%) |

No T2D N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 3,913 | 707 (18.1) | 3,206 (81.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Deaths | All causes | 1,800 | 385 (21.4) | 1,415 (78.6) |

| CRC-specific deaths | 678 | 111 (16.2) | 568 (83.4) | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | Male | 2,075 | 400 (19.3) | 1,675 (80.7) |

| Female | 1,838 | 307 (16.7) | 1,531 (83.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Age at baseline, years | <55 | 131 | 23 (17.6) | 108 (82.4) |

| ≤55 to <64 | 634 | 106 (16.7) | 528 (83.3) | |

| ≤65 to <74 | 1,503 | 275 (18.3) | 1,228 (81.7) | |

| ≥75 | 1,645 | 303 (18.4) | 1,342 (81.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Education, years | ≤12 | 1,936 | 370 (19.1) | 1,566 (80.9) |

| 13–15 | 1,128 | 204 (18.1) | 924 (81.9) | |

| ≥16 | 849 | 133 (15.7) | 716 (84.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | White | 689 | 78 (11.3) | 611 (88.7) |

| African American | 742 | 146 (19.7) | 596 (80.3) | |

| Native Hawaiian | 232 | 42 (18.1) | 190 (81.9) | |

| Japanese American American | 1,481 | 246 (16.6) | 1,235 (83.4) | |

| Latino | 769 | 195 (25.4) | 574 (74.6) | |

|

| ||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | <18.5 | 69 | 5 (7.3) | 64 (92.7) |

| 18.5–<25 | 1,457 | 144 (9.9) | 1,313 (90.1) | |

| 25–<30 | 1,552 | 311 (20.0) | 1,241 (80.0) | |

| ≥30 | 835 | 247 (29.6) | 588 (70.4) | |

|

| ||||

| Physical activity2 | <30 min/day | 1,591 | 346 (21.7) | 1,245 (78.3) |

| ≥30 min/day | 2,240 | 344 (15.4) | 1,896 (84.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking status2 | Never | 1,517 | 269 (17.7) | 1,248 (82.3) |

| Past | 1,719 | 347 (20.2) | 1,372 (79.8) | |

| Current | 640 | 85 (13.3) | 555 (86.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Comorbidity | 0 | 1,916 | 95 (5.0) | 1,821 (95.0) |

| 1 | 1,448 | 281 (19.4) | 1,167 (80.6) | |

| ≥2 | 549 | 331 (60.3) | 218 (39.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Family history of CRC2 | Yes | 2,945 | 519 (17.6) | 2,426 (82.4) |

| No | 417 | 67 (16.1) | 350 (83.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Stage of disease at diagnosis | In situ | 342 | 65 (19.0) | 277 (81.0) |

| Local | 1,887 | 338 (17.9) | 1,549 (82.1) | |

| Regional | 1,684 | 304 (18.1) | 1,380 (81.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor site | Colon | 2,995 | 549 (18.3) | 2,446 (81.7) |

| Rectum | 882 | 151 (17.1) | 731 (82.7) | |

| Mixed | 36 | 7 (19.4) | 29 (80.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor grade | 1–2 | 2,878 | 515 (17.9) | 2,363 (82.1) |

| 3–4 | 461 | 84 (18.2) | 377 (81.8) | |

| Missing | 574 | 108 (18.8) | 466 (81.2) | |

Only T2D cases detected before CRC diagnosis

Row percentages do not add up to 100% due to missing values

Japanese Americans represented the largest proportion of the study population, followed by Latinos, African Americans, whites, and Native Hawaiians. Whites had the lowest rate of T2D (11%), with higher rates among Japanese Americans (17%), Native Hawaiians (18%), African Americans (20%), and Latinos (25%). Native Hawaiians had the highest proportion of overweight and obese participants (89%) with lower rates among African Americans (76%), Latinos (74%), whites (62%), and Japanese Americans (44%). Stage of disease at diagnosis also differed by ethnicity. Latinos had the highest percentage of regional disease (46%) followed by Japanese American (44%), whites (42%), African Americans (40%), and Native Hawaiians (38%).

In total, 1,800 all-cause and 678 CRC-specific deaths were recorded. CRC-specific survival (Table 2) was not related to a T2D diagnosis (HR=0.84; 95% CI=0.67–1.07) in the entire study population, but the association differed according to comorbidity status (pinteraction=0.03). A history of T2D vs. no T2D predicted lower mortality in those without additional pre-existing conditions (HR=0.49; 95% CI=0.25–0.96), however, no association was seen in patients with comorbid conditions. Stratification by duration of known T2D also suggested differences. The association of T2D <10 years with CRC-specific mortality was inverse (HR=0.61; 95% CI=0.46–0.82), whereas T2D for ≥10 years predicted a higher mortality (HR=1.48; 95% CI=1.06–2.07). The interaction terms for sex, ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, tumor site, and family history of CRC were not significant in the CRC-specific models despite small differences in risk estimates.

Table 2.

CRC-specific Mortality Related to T2D in the Multiethnic Cohort1

| Characteristic | Category | HR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | All T2D Cases | 0.84 | 0.67 | 1.07 | |

|

| |||||

| T2D duration | <10 years | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.82 | |

| ≥10 years | 1.48 | 1.06 | 2.07 | ||

|

| |||||

| Sex | Men | 0.80 | 0.58 | 1.08 | |

| Women | 0.93 | 0.64 | 1.36 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.55 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity | White | 0.65 | 0.31 | 1.38 | |

| African American | 1.10 | 0.68 | 1.79 | ||

| Native Hawaiian | 0.55 | 0.16 | 1.83 | ||

| Japanese American | 0.75 | 0.48 | 1.16 | ||

| Latino | 0.95 | 0.59 | 1.52 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.59 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Stage of disease at diagnosis | In situ | NA2 | |||

| Local | 0.82 | 0.52 | 1.29 | ||

| Regional | 0.86 | 0.65 | 1.13 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.81 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Tumor site | Colon | 0.77 | 0.58 | 1.02 | |

| Rectum | 1.06 | 0.66 | 1.69 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.64 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Family history of CRC | No | 0.89 | 0.67 | 1.17 | |

| Yes | 0.56 | 0.26 | 1.22 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.81 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Comorbidity3 | None | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.96 | |

| 1+ | 1.08 | 0.85 | 1.38 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.03 | ||||

Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CIs were obtained by Cox regression adjusted for age, BMI (time-varying QX1–2), ethnicity, smoking status, education, physical activity, NSAID use, family history of CRC, comorbidity (heart attack and/or stroke)

Number of events is too small for analysis

HRs are for participants with T2D vs. those without a T2D history

T2D status was also not associated with overall all-cause mortality (Table 3), but in participants with pre-existing comorbidity, T2D was related to 36% higher mortality (95% CI=1.19–1.56; pinteraction=0.03). Also, in cases with rectal but not colon cancer, T2D predicted a higher mortality (HR=1.33; 95% CI=1.03–1.78). The significant interaction with ethnicity (pinteraction=0.04) was likely due to the 62% higher T2D-related mortality among Latinos (95% CI=1.24–2.11). All-cause mortality also appeared elevated for those with ≥10 years of T2D (HR=1.49; 95% CI=1.22–1.82) but not in those with shorter T2D duration. No significant interactions by sex, stage at diagnosis, and family history were detected.

Table 3.

All-cause Mortality Related to T2D in the Multiethnic Cohort1

| Characteristic | Category | HR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | All T2D Cases | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.27 | |

|

| |||||

| T2D duration | <10 years | 0.95 | 0.82 | 1.11 | |

| ≥10 years | 1.49 | 1.22 | 1.82 | ||

|

| |||||

| Sex | Men | 1.07 | 0.90 | 1.27 | |

| Women | 1.17 | 0.94 | 1.45 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.22 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity | White | 0.81 | 0.55 | 1.21 | |

| African American | 1.16 | 0.88 | 1.54 | ||

| Native Hawaiian | 0.74 | 0.39 | 1.38 | ||

| Japanese American | 0.98 | 0.77 | 1.25 | ||

| Latino | 1.62 | 1.24 | 2.11 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.04 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Stage of disease at diagnosis | In situ | 1.33 | 0.69 | 2.58 | |

| Local | 1.09 | 0.89 | 1.33 | ||

| Regional | 1.11 | 0.92 | 1.43 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.35 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Tumor site | Colon | 1.07 | 0.92 | 1.25 | |

| Rectum | 1.35 | 1.03 | 1.78 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.56 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Family history of CRC | No | 1.01 | 0.89 | 1.14 | |

| Yes | 0.97 | 0.61 | 1.55 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.81 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Comorbidity2 | None | 0.90 | 0.65 | 1.26 | |

| 1+ | 1.36 | 1.19 | 1.56 | ||

| PInteraction | 0.03 | ||||

Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CIs were obtained by Cox regression adjusted for age, BMI (time-varying QX1-2), ethnicity, smoking status, education, physical activity, NSAID use, family history of CRC, comorbidity (heart attack and/or stroke)

HRs are for participants with T2D vs. those without a T2D history

Adjustment for stage and treatment, i.e., radiotherapy and chemotherapy, did not substantially affect the results of the models. The respective HRs were 0.85 (95% CI=0.67–1.07) for CRC-specific mortality and 1.12 (95% CI=0.98–1.27) for all-cause mortality.

Discussion

The current study within a large population-based cohort of five ethnic groups detected no association of T2D before a CRC diagnosis with disease-specific and all-cause survival. However, among individuals with self-reports of additional comorbidity, those with T2D experienced lower survival than those without T2D. It also appeared that a longer known T2D duration predicted worse survival than the presence of T2D for <10 years, but caution is necessary as the exact time of T2D diagnosis was not known. The relation was consistent across subgroups defined by sex, tumor site (except for all-cause mortality), and family history of CRC. Ethnic differences in the association between T2D and mortality were minimal; a T2D history predicted worse all-cause survival among Latinos.

The current null results are in contrast to many publications reporting substantially lower survival for CRC patients with T2D than for those without. A large study with 500,000 CRC cases within the British health care system reported a 12–14% higher CRC-specific and a 23–24% higher all-cause mortality even after controlling for a large number of prognostic factors.12 A higher cancer-specific mortality was detected for men with T2D independent of T2D medication in a Danish registry-based analysis.10 For all-cause mortality, the majority of studies reported a 20–30% higher mortality for CRC patients with T2D than without T2D.9 Whereas one study detected higher overall mortality for patients with T2D compared to those without for colon (HR=1.28; 95% CI=1.14–1.42) and rectum (HR=1.48; 95% CI=1.28–1.73),1 a Scottish report described higher all-cause mortality for colon but not rectal cancer.16 In a retrospective study of SEER and Medicare data,11 a higher overall mortality was observed in colon cancer patients with elevated glucose/T2D across all stages (HR=1.17; 95% CI=1.13–1.21). On the other hand, several studies also reported null associations for T2D and all-cause mortality in CRC patients, e.g., a retrospective cohort based on 350 U.K. primary care practices,13 1,029 non-metastatic CRC cases in China,15 and an analysis of 1,127 CRC cases.14

Possible reasons for discrepant findings across studies include duration and severity of T2D; adverse effects of T2D on survival may depend on years of experiencing T2D as demonstrated by differential risk estimates according to duration in the current analysis. Alternatively, more frequent contact with health care personnel among patients with diagnosed T2D than those without T2D may encourage screening and early detection. A colonoscopy with removal of polyps and/or a change in lifestyle at an earlier stage of the disease may contribute to a slower progression of CRC. Different rates of undiagnosed T2D and Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT), which is highly prevalent in some populations26, may influence the results.27 Finally, the type of T2D medication used within a study population may affect survival. Metformin use predicted better all-cause survival than other T2D medications in several reports,28–30 but medication data in the MEC is limited to QX3 participants.

The small ethnic differences in the current analysis may be due to health care access and utilization. For example, CRC screening rates as reported by the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey System31 were higher in Japanese Americans (75%) than in whites (69%) and Native Hawaiians (59%) in Hawaii and higher for whites (61%) than African Americans (59%) and Latinos (38%) in California. This behavior may explain the lower proportion of regional stage disease and the higher all-cause mortality among Latinos.

Strengths of the current study include the longitudinal study design allowing data to be collected over 24 years and the large number of ethnically diverse cases with relatively similar access to health care. Limitations include the lack of detailed information about treatment, especially beyond the first course of cancer treatment, and the exact time of T2D diagnosis. The known T2D duration used for the current analysis may be biased by age at cohort entry, questionnaire participation, and availability of claims data. As no glucose measurements were obtained in cohort members, possible undiagnosed T2D and IGT may have caused exposure misclassification and biased the association toward the null. Other limitations include the small sample sizes in some ethnic groups, the lack of information on colonoscopy screening, and the possibility of behavioral changes after being diagnosed with CRC or T2D.

In this large multiethnic population with overall null findings, CRC patients with T2D and other chronic conditions, such as heart disease or stroke, experienced worse survival than those without T2D. Also, a long history of T2D predicted lower survival. Disparate survival among CRC patients with T2D across populations may be the result of screening practices, lifestyle behavior, and treatment. Based on the current data, CRC patients may not experience higher mortality despite a pre-existing T2D as long as they are in good cardiovascular health.

Novelty and Impact Statement.

Although several previous analyses have evaluated the influence of T2D on the prognosis of CRC patients, this is the first report from a population with diverse ethnic groups who experience a high incidence of T2D. No association between T2D and CRC-specific and all-cause survival was observed except in participants with other comorbid conditions or long T2D duration. Apart from for lower all-cause survival in Latinos, ethnic differences were minimal.

Acknowledgments

The Multiethnic Cohort was supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: R37CA54281 (L.N. Kolonel), U01CA164973 (L. Le Marchand, L.R. Wilkens, C.A. Haiman), R21DK073816 (G. Maskarinec). The tumor registries are supported by NCI contracts HHSN261201300009I/HHSN26100005 and HHSN 261201300004I-2-26100005-2.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors has a conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.van de Poll-Franse LV, Houterman S, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Dercksen MW, Coebergh JW, Haak HR. Less aggressive treatment and worse overall survival in cancer patients with diabetes: a large population based analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1986–1992. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M. [6-20-2016];SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013. 2016 http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/

- 3.International Diabetes Federation. [10-7-2016];IDF Diabetes Atlas. 2015 http://www.diabetesatlas.org/ [PubMed]

- 4.Cheng I, Caberto CP, Lum-Jones A, Seifried A, Wilkens LR, Schumacher FR, Monroe KR, Lim U, Tiirikainen M, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Stram DO, et al. Type 2 diabetes risk variants and colorectal cancer risk: the Multiethnic Cohort and PAGE studies. Gut. 2011;60:1703–1711. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.237727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, Bergenstal RM, Gapstur SM, Habel LA, Pollak M, Regensteiner JG, Yee D. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1674–1685. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1679–1687. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer HU, Schottker B, Raum E, Brenner H. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis on sex-specific differences. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell PT, Deka A, Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Hildebrand JS, McCullough ML, Limburg PJ, Gapstur SM. Prospective study reveals associations between colorectal cancer and type 2 diabetes mellitus or insulin use in men. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1138–1146. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, Peairs KS, Stein KB, Derr RL, Wolff AC, Brancati FL. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2754–2764. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranc K, Jorgensen ME, Friis S, Carstensen B. Mortality after cancer among patients with diabetes mellitus: effect of diabetes duration and treatment. Diabetologia. 2014;57:927–934. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Mauldin PD, Ebeling M, Hulsey TC, Liu B, Thomas MB, Camp ER, Esnaola NF. Effect of metabolic syndrome and its components on recurrence and survival in colon cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119:1512–1520. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Development and validation of risk prediction equations to estimate survival in patients with colorectal cancer: cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2497. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Currie CJ, Poole CD, Jenkins-Jones S, Gale EA, Johnson JA, Morgan CL. Mortality after incident cancer in people with and without type 2 diabetes: impact of metformin on survival. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:299–304. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmadi A, Noroozi M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Hashemi-Nazari SS. Effect of metabolic syndrome and its components on survival in colorectal cancer: a prospective study. J Renal Inj Prev. 2015;4:15–19. doi: 10.12861/jrip.2015.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.You J, Liu WY, Zhu GQ, Wang OC, Ma RM, Huang GQ, Shi KQ, Guo GL, Braddock M, Zheng MH. Metabolic syndrome contributes to an increased recurrence risk of non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19880–19890. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker JJ, Brewster DH, Colhoun HM, Fischbacher CM, Lindsay RS, Wild SH. Cause-specific mortality in Scottish patients with colorectal cancer with and without type 2 diabetes (2000–2007) Diabetologia. 2013;56:1531–1541. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2917-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maskarinec G, Erber E, Grandinetti A, Verheus M, Oum R, Hopping BN, Schmidt MM, Uchida A, Juarez DT, Hodges K, Kolonel LN. Diabetes incidence based on linkages with health plans: the multiethnic cohort. Diabetes. 2009;58:1732–1738. doi: 10.2337/db08-1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ollberding NJ, Nomura AM, Wilkens LR, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Racial/ethnic differences in colorectal cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1899–1906. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Hankin JH, Nomura AM, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, Stram DO, Monroe KR, Earle ME, Nagamine FS. A multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:346–357. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stram DO, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR, Henderson B, Kolonel LN. Calibration of the dietary questionnaire for a multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:358–370. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson RE, Emond JA, Natarajan L, Wesseling-Perry K, Kolonel LN, Jardack P, Ancoli-Israel S, Arab L. Short sleep duration is associated with higher energy intake and expenditure among African-American and non-Hispanic white adults. J Nutr. 2014;144:461–466. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.186890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setiawan VW, Virnig BA, Porcel J, Henderson BE, Le ML, Wilkens LR, Monroe KR. Linking data from the Multiethnic Cohort Study to Medicare data: linkage results and application to chronic disease research. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:917–919. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maskarinec G, Harmon BE, Little MA, Ollberding NJ, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Le ML, Wilkens LR. Excess body weight and colorectal cancer survival: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:1709–1718. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0664-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. [7-14-2017];Data and Reports. 2017 https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/hid/

- 25.Jacobs S, Harmon BE, Ollberding NJ, Wilkens LR, Monroe KR, Kolonel LN, Le ML, Boushey CJ, Maskarinec G. Among 4 Diet Quality Indexes, Only the Alternate Mediterranean Diet Score Is Associated with Better Colorectal Cancer Survival and Only in African American Women in the Multiethnic Cohort. J Nutr. 2016;146:1746–1755. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.234237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grandinetti A, Kaholokula JK, Theriault AG, Mor JM, Chang HK, Waslien C. Prevalence of diabetes and glucose intolerance in an ethnically diverse rural community of Hawaii. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:250–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergman M, Chetrit A, Roth J, Dankner R. One-hour post-load plasma glucose level during the OGTT predicts mortality: observations from the Israel Study of Glucose Intolerance, Obesity and Hypertension. Diabet Med. 2016;33:1060–1066. doi: 10.1111/dme.13116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulus JK, Williams CD, Cossor FI, Kelley MJ, Martell RE. Metformin, Diabetes, and Survival among U.S. Veterans with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1418–1425. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell JM, Bellman SM, Stephenson MD, Lisy K. Metformin reduces all-cause mortality and diseases of ageing independent of its effect on diabetes control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;40:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng F, Song L, Wang W. Metformin Improves Overall Survival of Colorectal Cancer Patients with Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:5063239. doi: 10.1155/2017/5063239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [7-17-2017];Chronic Disease and Health Promotion Data & Indicators. 2017 https://chronicdata.cdc.gov/health-area/chronic-disease-indicators.