Abstract

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is highly heritable. Physical activity, physical inactivity and body mass index (BMI) are also risk factors, but evidence of interaction between genetic and environmental risk factors is limited.

Methods

Data on 2,134 VTE cases and 3,890 matched controls were obtained from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II), and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS). We calculated a weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) using 16 single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with VTE risk in published GWAS. Data on three risk factors, physical activity (metabolic equivalent [MET] hours per week), physical inactivity (sitting hours per week) and BMI, were obtained from biennial questionnaires. VTE cases were incident since cohort inception; controls were matched to cases on age, cohort, and genotype array. Using conditional logistic regression, we assessed joint effects and interaction effects on both additive and multiplicative scales. We also ran models using continuous wGRS stratified by risk-factor categories.

Results

We observed a supra-additive interaction between wGRS and BMI. Having both high wGRS and high BMI was associated with a 3.4-fold greater risk of VTE (relative excess risk due to interaction = 0.69, p=0.046). However, we did not find evidence for a multiplicative interaction with BMI. No interactions were observed for physical activity or inactivity.

Conclusion

We found a synergetic effect between a genetic risk score and high BMI on the risk of VTE. Intervention efforts lowering BMI to decrease VTE risk may have particularly large beneficial effects among individuals with high genetic risk.

Keywords: body mass index, genetic risk score, physical activity, physical inactivity, venous thromboembolism

INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major health problem with 350,000 – 900,000 incident cases per year in the United States (Wendelboe et al., 2015). VTE comprises two conditions, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). PE is the more severe form of VTE, as patients with PE have an 18-fold greater risk of early death than patients with DVT alone (Heit et al., 1999). It is well-known that VTE is a multifactorial disease, with both genetic and lifestyle risk factors contributing to the development of VTE (Heit, 2015; Rosendaal, 1999a). However, it is less well understood how these factors interact to influence VTE risk.

Lifestyle factors, including physical activity, physical inactivity, and body mass index (BMI), appear to be associated with the risk of VTE (Hull & Harris, 2015; Kabrhel, Varraso, Goldhaber, Rimm, & Camargo, 2009; Varraso, Kabrhel, Goldhaber, Rimm, & Camargo, 2012). Over the last few decades, growing evidence has shown that prolonged seated immobility, for example, due to long-distance air travel or sedentary occupations, can provoke development of VTE. (Braithwaite, Healy, Cameron, Weatherall, & Beasley, 2016; Healy, Levin, Perrin, Weatherall, & Beasley, 2010; Hughes et al., 2003; Lapostolle et al., 2001; Siniarski, Wypasek, Fijorek, Gajos, & Undas, 2014) A large population-based cohort and a hospital-based case-control study found that long sitting time was significantly associated with a greater risk of VTE (Kabrhel, Varraso, Goldhaber, Rimm, & Camargo, 2011; West, Perrin, Aldington, Weatherall, & Beasley, 2008). The association of physical activity with VTE is somewhat less clear. Some previous studies reported that individuals who exercised intensively (e.g., trained athletes) had a greater risk of VTE than those who exercised lightly (Baggish & Wood, 2011; Hurley, Comins, Green, & Canizzaro, 2006; Tao & Davenport, 2010). A small observational study that included healthy athletes in marathons, triathlons, and cycling found significant higher platelet activity during marathon running, suggesting prolonged exercise may be associated with elevated risk of thromboembolic events (Hanke et al., 2010). BMI is highly associated with both physical inactivity and activity, but is also a strong, independent risk factor for VTE (Eichinger et al., 2008; Oren, Smith, Doggen, Heckbert, & Lemaitre, 2006; Severinsen et al., 2009).

Family and twin studies demonstrate that VTE risk is highly (50%–60%) heritable (Heit et al., 2004; Souto et al., 2000; Zoller, Ohlsson, Sundquist, & Sundquist, 2017). Candidate and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified seven VTE-associated susceptibility genes (ABO, F2, F5, F11, FGG, PROCR, and NME7) (Germain et al., 2011; Greliche et al., 2013; Heit et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2013; Tregouet et al., 2009). A large meta-analysis of GWAS identified two additional susceptibility genes on chromosomes 10 and 19 (TSPAN15 and SLC44A2) (Germain et al., 2015), and recently, two GWAS newly identified F8 and ZFPM2 genes on X chromosome and chromosome 8, respectively (Hinds et al., 2016; Klarin et al., 2017).

However, current evidence regarding how genetic susceptibility to VTE may interact with lifestyle risk factors, in particular physical activity or inactivity, is very limited. Thus, we assessed interaction effects between VTE-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and physical activity and inactivity in three large nested case-control studies. We additionally examined the interaction effects with body mass index (BMI), as BMI is highly associated with both physical activity and inactivity.

METHODS

Study population

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) is a large prospective cohort that was established in 1976 and recruited 121,701 female registered nurses aged 30 – 55 years in 11 populous states in the United States. Details of the cohort and protocols have been previously described (Colditz & Hankinson, 2005). Briefly, survey questionnaires regarding health and lifestyle factors have been sent to participants and completed biennially since cohort inception. Biologic specimens, including blood samples, were collected from 32,826 participants between 1989 and 1990. Additionally, blood samples of 30,000 participants were collected in 2002.

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II) cohort was established in 1989, including 116,430 female registered nurses in 15 US states (Colditz & Hankinson, 2005). These nurses, aged of 25 – 42 years, were younger at baseline than those in the original NHS cohort. Similar to the NHS, study participants provided information by completing biennial questionnaires. 29,611 participants provided biologic specimens including blood samples between 1996 and 1999. Later, 30,000 additional participants provided blood samples in 2006.

The Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) is a prospective study of 51,529 US male health professionals (dentists, pharmacists, optometrists, osteopathic physicians, podiatrists, and veterinarians) aged 40–75 years who enrolled in 1986 (Rimm et al., 1991). Since its inception, study participants were followed with biennial questionnaires to update information on health and lifestyle. Between 1993 and 1995, 18,159 participants provided biologic specimens, including blood samples. In 2005, 18,000 participants additionally provided blood samples.

Analysis of these cohort data was approved by the Human Research Committee of Partners Healthcare and the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Genomic data

The NHS, NHS II, and HPFS subjects eligible for inclusion in this study were previously genotyped as part of a case-control GWAS of VTE (1,801 VTE cases, 1,801 VTE controls in our study) and GWAS of other endpoints, including several cancers, type II diabetes, and coronary heart disease (4,396 subjects total, 1,099 of whom were diagnosed with VTE after cohort inception; Supplementary Table 1). Details describing genotype data from the three cohorts were previously reported elsewhere (Lindstrom et al., 2017). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples and genotyping was carried out using five genotype arrays (Affymetrix 6.0, Illumina HumanHap, Illumina OmniExpress, OncoArray, and HumanCore Exome). After basic quality control, genotype data were imputed based on 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 haplotypes as reference panels using Minimac 3 program (Das et al., 2016). The total number of imputed genotype variants (autosomal SNPs) was 46,672,816 and the average imputation quality score (minor allele frequency ≥ 5%) ranged from 0.81 to 0.97.

For analysis, we selected 16 VTE-associated SNPs previously identified in large-scale GWAS or meta-analyses (Germain et al., 2015; Germain et al., 2011; Greliche et al., 2013; Heit et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2013; Tregouet et al., 2009); rs6025, rs1018827, rs6427196, rs1799963, rs3756008, rs4253399, rs7659024, rs6536024, rs6087685, rs2519093, rs495828, rs505922, rs687621, rs16861990, rs2288904, and rs78707713. Most of these variants were independent of each other, though some of them were on the same gene. To examine the overall genetic burden on VTE risk, we generated a weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) using the 16 SNPs, which was the sum of the risk allele counts where each SNP was assigned weights defined as the SNP-specific beta coefficients reported in the published studies (Supplementary Table 2).

Risk factor data

We obtained data on physical activity, physical inactivity, and BMI from biennial questionnaires mailed to each cohort. We used the total metabolic equivalent task (MET)-hour per week to estimate leisure time physical activity. MET-hour score was calculated by summing the product of a MET-value for each physical activity (e.g., walking, jogging) with total hours of that individual activity (Ainsworth et al., 1993). To estimate physical inactivity on an average week, we used participant responses to all questions regarding time spent sitting per week (hours/week). To calculate the total sitting time per week, we combined time sitting (hours/week) reported for various activities including sitting at work, sitting at home reading, and television watching. Because in this case some participants had sitting time totaled greater than the total number of hours in a week (168 hours), we set maximum total time spent sitting as 168 hours per week. Validity of self-reported physical activity, measured as MET-hour, and sitting time have been reported elsewhere (validity correlation: r = 0.79 and 0.41, respectively) (Chasan-Taber et al., 1996; Wolf et al., 1994). BMI was calculated using weight in kg/height in m2. Height was reported on the baseline questionnaire and assumed to be stable over time. Weight was updated using biennial questionnaire data. In a prior validity study, self-reported weight was reported to be highly accurate as compared to weighted measured by trained technicians (r = 0.97) (Rimm et al., 1990). For analysis, risk factor data were extracted from the questionnaire just prior to diagnosis for cases; the same questionnaire cycle was used for the matched controls. We carried forward up to two cycles of prior data if data were missing at the reference time.

Outcome data

Cases were defined as incident VTE cases who self-reported either a physician-diagnosed DVT or PE during the cohort follow-up (1976 – 2014 in NHS, 1989 – 2011 in NHS II, 1986 – 2012 in HPFS) on biennial questionnaires. For NHS and HPFS subjects genotyped for the VTE GWAS, controls were not diagnosed with VTE prior to the date of the matched case's diagnosis, and were matched to cases on age at baseline and cohort (gender). For subjects genotyped as part of GWAS of other endpoints, controls were defined as participants who never reported VTE over the entire follow-up period. We matched incident cases from these GWAS to controls with a ratio of 1:3 based on age at blood draw (grouped by a 2-year age window), cohort, and genotype platform.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of matched cases and controls were tabulated with frequencies and means of risk factors (BMI, MET-hour, sitting time, and wGRS). We used conditional logistic regression to take into account the matching design in all analyses. First, we examined marginal effects of risk factors. BMI, MET-hour, and sitting time were simultaneously examined in a multivariable regression model adjusting for the others as covariates. The wGRS was examined with univariate regression. All descriptive analyses were performed twice: in a primary approach we treated the risk factor of interest as a continuous variable (i.e. per 5 kg/m2 in BMI, 25 MET-score hours/week in MET, 25 sitting hours/week in sitting time, and, standardized wGRS) and in a secondary approach we used categorized values (BMI: 18.5 – < 24.9, 25 – 29.9, and ≥ 30; quartiles for MET-hours, sitting time, and wGRS). Quartile groups were generated using the quartile cutoffs in controls. wGRS was standardized with mean of 0 and standard deviation (SD) of 1.

Interaction tests were performed using multivariable regression models with arbitrarily dichotomized risk factors (low BMI: 18.5 – < 30, high BMI: ≥ 30; low MET-hours: 1st quartile, high MET-hours: 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartile; low sitting time: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd quartile, high sitting time: 4th quartile; low wGRS: 1st and 2nd quartile, and high wGRS: 3rd and 4th quartile). For each of the three non-genetic risk factors, we assessed for interaction with wGRS on both the additive and multiplicative scale. Additive interactions were assessed using the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) estimated by the delta method (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 1992). The RERI is a widely used measurement of departure from additivity of effects on the absolute risk scale, which can be calculated using relative risks as RR(AB) − RR(AB̅) − RR(A̅B) + 1 where A and B are dichotomous exposure variables of interest (Richardson & Kaufman, 2009). Multiplicative interaction was assessed using odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% CI of the product term between wGRS and the risk factor.

In addition, we assessed the homogeneity of effects of wGRS and VTE risk across categories of BMI, physical activity, and sitting time. Multiplicative interactions using categorical and continuous risk factors were examined with likelihood ratio tests (2 or 3 degree of freedom) and Wald tests (1 degree of freedom), respectively. We also assessed interactions with the individual SNPs that were included in the wGRS to identify any SNP-specific interaction effects. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R package (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

We identified 2,900 cases and 5,098 matched controls in this study. Because in NHS MET-hour and sitting time have been measured since 1986, matched samples for which cases were diagnosed before 1986 in NHS were excluded (n = 401 cases and 619 controls). In all cohorts, we excluded subjects missing information on BMI, MET-hours, or sitting time (n = 262 cases and 345 controls). We also excluded subjects whose BMI was less than 18.5 to reduce the likely effect of comorbidity (e.g. cancer) (n = 17 cases and 63 controls). If samples did not have any matched counterparts due to the aforementioned two exclusion criteria (n = 86 cases and 181 controls), we excluded the subjects. Ultimately, 6,024 subjects (2,134 cases and 3,890 controls) remained in our analysis.

Characteristics of the cases and controls are described in Table 1. Cases were more obese and had less physical activity but more sitting time and a higher wGRS. Table 2 shows the adjusted associations between three risk factors (as either continuous or categorical variables) and VTE risk. BMI was significantly associated with a greater risk of VTE, adjusting for MET-hour and siting time (50% greater VTE risk per 5 kg/m2 higher BMI [95% CI = 1.42 – 1.59]; OR of BMI 25 – < 30 vs. BMI 18.5 – < 25 = 1.44 [95% CI = 1.26 – 1.64], OR of BMI ≥ 30 vs. BMI 18.5 – < 25 = 2.74 [95% CI = 2.35 – 3.21], and P-trend < .0001). Adjusting for other factors, physical activity, measured in quartiles of MET-hours, was significantly associated with a lower risk of VTE (OR of 2nd quartile vs. 1st quartile = 0.80 [95% CI = 0.69 – 0.94], OR of 4th quartile vs. 1st quartile = 0.71 [95% CI = 0.60 – 0.84], P-trend = 0.006). However, this association was not observed in our continuous MET-hour (per 25 MET-hour/week) analysis. Physical inactivity, measured in quartiles of time sitting, showed an increasing trend in the association with the risk of VTE (OR of 2nd quartile vs. 1st quartile = 1.16 [95% CI = 0.98 – 1.37], OR of 4th quartile vs. 1st quartile = 1.15 [95% CI = 0.98 – 1.36], p for trend = 0.0026). However, this association was not significant in both categorical and continuous analyses. Table 3 shows that our wGRS has a linear and positive association with VTE risk (36% increase in VTE risk per 1 SD [95% CI = 1.29 – 1.44]; OR of 2nd quartile vs. 1st quartile = 1.23 [95% CI = 1.04 – 1.46], OR of 3rd quartile vs. 1st quartile = 1.33 [95% CI = 1.13 – 1.57], OR of 4th quartile vs. 1st quartile = 2.07 [95% CI = 1.76 – 2.43], P-trend < .0001).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of matched cases and controls in NHS, NHSII, HPFS, and pooled data

| NHS (N= 2,450) | NHSII (N= 1,766) | HPFS (N= 1,808) | Pooled data (N= 6,024) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Variable | Cases (N = 889) |

Controls (N = 1,561) |

Variable | Cases (N = 447) |

Controls (N = 1,319) |

Variable | Cases (N = 798) |

Controls (N = 1,010) |

Variable | Cases (N = 2,134) |

Controls (N = 3,890) |

| MET (hr/wk), mean (SD) | 16.2 (21.5) | 19.4 (22.7) | MET (hr/wk), mean (SD) | 18.3 (23.3) | 21.5 (30.7) | MET (hr/wk), mean (SD) | 36.8 (48.1) | 39.5 (40.1) | MET (hr/wk), mean (SD) | 24.3 (35.6) | 25.4 (31.9) |

| MET (range), % | MET (range), % | MET (range), % | MET (range), % | ||||||||

| Q1 (< 4.0) | 31.5 | 24.8 | Q1 (< 5.2) | 31.1 | 24.6 | Q1 (< 12.0) | 33.6 | 24.8 | Q1 (< 5.6) | 29.6 | 24.9 |

| Q2 (4.0 – < 11.5) | 24.5 | 24.7 | Q2 (5.2 – < 13.1) | 23.3 | 25.3 | Q2 (12.0 – < 26.9) | 22.3 | 25.3 | Q2 (5.6 – < 15.4) | 24.2 | 25.1 |

| Q3 (11.5– < 26.4) | 25.1 | 25.4 | Q3 (13.1 – < 28.4) | 25.1 | 25.1 | Q3 (26.9 – < 55.1) | 22.7 | 25.0 | Q3 (15.4 – < 33.8) | 23.7 | 25.0 |

| Q4 (26.4 +) | 18.9 | 25.1 | Q4 (28.4 +) | 20.6 | 25.0 | Q4 (55.1 +) | 21.4 | 25.1 | Q4 (33.8 +) | 22.5 | 25.0 |

| Sitting time¶ (hr/wk), mean (SD) | 37.4 (25.0) | 35.8 (23.5) | Sitting time¶ (hr/wk), mean (SD) | 34.8 (23.9) | 33.8 (21.9) | Sitting time¶ (hr/wk), mean (SD) | 55.4 (42.7) | 54.6 (42.4) | Sitting time¶ (hr/wk), mean (SD) | 43.6 (33.8) | 40.0 (30.5) |

| Sitting time (range), % | Sitting time (range), % | Sitting time (range), % | Sitting time (range), % | ||||||||

| Q1 (< 19.5) | 23.4 | 23.7 | Q1 (< 17.0) | 21.9 | 24.5 | Q1 (< 15.5) | 22.8 | 24.0 | Q1 (< 17.0) | 23.2 | 24.3 |

| Q2 (19.5 – < 31.5) | 21.5 | 23.9 | Q2 (17.0 – < 31.0) | 27.7 | 25.4 | Q2 (15.5 – < 47.1) | 27.1 | 26.0 | Q2 (17.0 – < 32.0) | 23.5 | 25.3 |

| Q3 (31.5 – < 49.5) | 28.4 | 27.2 | Q3 (31.0 – < 46.5) | 23.7 | 24.2 | Q3 (47.1 – < 85.0) | 25.2 | 25.0 | Q3 (32.0 – < 54.0) | 22.1 | 24.7 |

| Q4 (49.5 +) | 26.8 | 25.2 | Q4 (46.5 +) | 26.6 | 25.9 | Q4 (85.0 +) | 24.9 | 25.1 | Q4 (54.0 +) | 31.2 | 25.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.0 (5.5) | 25.9 (4.9) | BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 30.4 (8.5) | 26.5 (5.6) | BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.2 (4.4) | 25.9 (3.5) | BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.2 (6.0) | 26.1 (4.8) |

| BMI, % | BMI, % | BMI, % | BMI, % | ||||||||

| 18.5 – < 25 | 34.4 | 49.7 | 18.5 – < 25 | 30.2 | 48.2 | 18.5 – < 25 | 31.5 | 42.5 | 18.5 – < 25 | 32.4 | 47.3 |

| 25 – < 30 | 34.1 | 32.9 | 25 – < 30 | 26.2 | 30.5 | 25 – < 30 | 48.1 | 46.7 | 25 – < 30 | 37.7 | 35.7 |

| 30 + | 31.5 | 17.4 | 30 + | 43.6 | 21.3 | 30 + | 20.4 | 10.8 | 30 + | 29.9 | 17.0 |

| Weighted GRS, mean (SD) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.0) | Weighted GRS, mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.0) | Weighted GRS, mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.0) | Weighted GRS, mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.0) |

| Weighted GRS (range), % | Weighted GRS (range), % | Weighted GRS (range), % | Weighted GRS (range), % | ||||||||

| Q1 (<2.7) | 18.0 | 25.0 | Q1 (< 2.7) | 17.7 | 25.0 | Q1 (< 2.7) | 16.9 | 25.0 | Q1 (< 2.7) | 17.9 | 25.0 |

| Q2 (2.7 – < 3.3) | 21.8 | 25.1 | Q2 (2.7 – < 3.3) | 21.9 | 24.9 | Q2 (2.7 – < 3.2) | 22.2 | 25.1 | Q2 (2.7 – < 3.3) | 21.7 | 25.0 |

| Q3 (3.3 – < 4.0) | 27.2 | 25.0 | Q3 (3.3 – < 3.9) | 22.8 | 25.1 | Q3 (3.2 – < 3.9) | 22.9 | 25.1 | Q3 (3.3 – < 3.9) | 24.3 | 25.0 |

| Q4 (4.0 +) | 33.0 | 25.0 | Q4 (3.9 +) | 37.6 | 24.9 | Q4 (3.9 +) | 38.0 | 25.0 | Q4 (3.9 +) | 36.1 | 25.0 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation; MET, metabolic equivalent task; Q, quartile; GRS, genetic risk score

Q1,2,3, and 4: quartile cutoffs were determined based on quartiles of controls within each cohort or in pooled data.

Sitting time refers a total sitting time (hour) per week, including ‘sitting at work’, ‘sitting at computer’, ‘sitting while driving’, ‘sitting at home watching TV’, ‘sitting at home reading books’, and ‘other sitting at home’.

Table 2.

Association of BMI, MET-hour, and sitting time with the risk of VTE

| NHS (N= 2,450) | NHS II (N= 1,766) | HPFS (N= 1,808) | Pooled data (N= 6,024) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Control N |

Case N |

Adjusted OR |

(95% CI) | Control N |

Case N |

Adjusted OR |

(95% CI) | Control N |

Case N |

Adjusted OR |

(95% CI) | Control N |

Case N |

Adjusted OR |

(95% CI) | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| BMI | 1561 | 889 | 1.46 | (1.33–1.60) | 1319 | 447 | 1.52 | (1.39–1.65) | 1,010 | 798 | 1.52 | (1.33–1.73) | 3,890 | 2,134 | 1.50 | (1.42–1.59) |

| MET | 1561 | 889 | 0.90 | (0.81–1.00) | 1319 | 447 | 0.96 | (0.86–1.08) | 1,010 | 798 | 0.98 | (0.93–1.04) | 3,890 | 2,134 | 0.96 | (0.92–1.01) |

| Sitting time | 1561 | 889 | 1.05 | (0.96–1.16) | 1319 | 447 | 0.98 | (0.87–1.11) | 1,010 | 798 | 1.01 | (0.95–1.07) | 3,890 | 2,134 | 1.01 | (0.97–1.06) |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| BMI | ||||||||||||||||

| 18.5 – < 25.0 | 776 | 306 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 636 | 135 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 429 | 251 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 1,841 | 692 | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| 25.0 – < 30.0 | 514 | 303 | 1.47 | (1.20–1.80) | 402 | 117 | 1.45 | (1.09–1.93) | 472 | 384 | 1.36 | (1.10–1.68) | 1,388 | 804 | 1.44 | (1.26–1.64) |

| 30.0 + | 271 | 280 | 2.67 | (2.09–3.41) | 281 | 195 | 3.36 | (2.54–4.44) | 109 | 163 | 2.28 | (1.69–3.07) | 661 | 638 | 2.74 | (2.35–3.21) |

| P-trend¶ | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||||||

| MET | ||||||||||||||||

| Quartile 1 | 387 | 280 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 325 | 139 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 250 | 268 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 969 | 632 | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 386 | 218 | 0.77 | (0.60–0.98) | 333 | 104 | 0.80 | (0.59–1.09) | 255 | 178 | 0.67 | (0.51–0.88) | 976 | 516 | 0.80 | (0.69–0.94) |

| Quartile 3 | 396 | 223 | 0.85 | (0.66–1.08) | 331 | 112 | 0.92 | (0.68–1.25) | 252 | 181 | 0.69 | (0.52–0.91) | 972 | 505 | 0.84 | (0.72–0.99) |

| Quartile 4 | 392 | 168 | 0.70 | (0.54–0.90) | 330 | 92 | 0.83 | (0.60–1.15) | 253 | 171 | 0.66 | (0.49–0.87) | 973 | 481 | 0.71 | (0.60–0.84) |

| P-trend¶ | 0.0007 | 0.3973 | 0.0199 | 0.0060 | ||||||||||||

| Sitting time | ||||||||||||||||

| Quartile 1 | 370 | 208 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 323 | 98 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 242 | 182 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 944 | 496 | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 373 | 191 | 1.00 | (0.77–1.29) | 335 | 124 | 1.36 | (0.99–1.87) | 263 | 216 | 1.18 | (0.89–1.56) | 983 | 501 | 1.16 | (0.98–1.37) |

| Quartile 3 | 424 | 252 | 1.16 | (0.91–1.49) | 319 | 106 | 1.11 | (0.80–1.53) | 252 | 201 | 1.10 | (0.82–1.48) | 962 | 471 | 1.04 | (0.88–1.23) |

| Quartile 4 | 394 | 238 | 1.12 | (0.87–1.44) | 342 | 119 | 1.04 | (0.76–1.43) | 253 | 199 | 1.13 | (0.83–1.52) | 1,001 | 666 | 1.15 | (0.98–1.36) |

| P-trend¶ | 0.0687 | 0.4504 | 0.5680 | 0.0026 | ||||||||||||

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task

Model 1 was a multivariable conditional logistic regression including three continuous variables simultaneously (BMI per 5 kg/m2, MET per 25 MET-score hour/week, and Sitting time per 25 sitting time hour/week). The adjusted OR was estimated adjusting for the other two factors.

Model 2 was a multivariable conditional logistic regression including three categorical variables simultaneously (BMI: 18.5–<25.0, 25.0–<30.0, 30+, MET: Quartile 1, 2, 3, 4, and Sitting time Quartile 1, 2, 3, 4). Similar to the Model 1, adjusted OR was estimated adjusting for the others.

Quartile cutoffs of MET: 4.0/11.5/26.4 in NHS, 5.2/13.1/28.4 in NHS II, 12.0/26.9/55.1 in HPFS, and 5.6/15.4/33.8 in the pooled data

Quartile cutoffs of sitting time: 19.5/31.5/49.5 in NHS, 17.0/31.0/46.5 in NHS II, 15.5/47.1/85.0 in HPFS, and 17.0/32.0/54.0 in the pooled data

P-trend was calculated with ordinal format of the categorical variables using the median value in each category

Table 3.

Association of wGRS with the risk of VTE

| NHS (N= 2,450) | NHSII (N= 1,766) | HPFS (N= 1,808) | Pooled data (N= 6,024) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Control N |

Case N |

OR | (95% CI) | Control N |

Case N |

OR | (95% CI) | Control N |

Case N |

OR | (95% CI) | Control N |

Case N |

OR | (95% CI) | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| wGRS-S | 1561 | 889 | 1.29 | (1.19–1.41) | 1319 | 447 | 1.38 | (1.24–1.53) | 1,010 | 798 | 1.46 | (1.31–1.62) | 3,890 | 2,134 | 1.36 | (1.29–1.44) |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| wGRS-S | ||||||||||||||||

| Quartile 1 | 391 | 160 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 330 | 79 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 252 | 135 | 1.00 | (Reference) | 972 | 381 | 1.00 | (Reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 389 | 194 | 1.22 | (0.93–1.58) | 329 | 98 | 1.25 | (0.89–1.74) | 253 | 177 | 1.31 | (0.98–1.77) | 973 | 464 | 1.23 | (1.04–1.46) |

| Quartile 3 | 391 | 242 | 1.44 | (1.12–1.85) | 330 | 102 | 1.29 | (0.92–1.81) | 253 | 183 | 1.35 | (1.00–1.82) | 973 | 519 | 1.33 | (1.13–1.57) |

| Quartile 4 | 390 | 293 | 1.87 | (1.46–2.40) | 330 | 168 | 2.12 | (1.56–2.90) | 252 | 303 | 2.28 | (1.72–3.01) | 972 | 770 | 2.07 | (1.76–2.43) |

| P-trend¶ | < .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 | < .0001 | ||||||||||||

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; wGRS-S, a standardized weighted genetic risk score with mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1

Model 1 was a univariable conditional logistic regression including the continuous standardized wGRS.

Model 2 was a univariable conditional logistic regression including the categorical standardized wGRS.

Quartile cutoffs in wGRS-S: −0.72/−0.24/0.38 in NHS, −0.74/−0.25/0.31 in NHS II, −0.75/−0.26/0.29 in HPFS, and −0.74/−0.25/0.33 in the pooled data

P-trend was calculated with ordinal format of the categorical variables using the median value in each category

We assessed interaction effects using dichotomous risk factors (high/low) using additive and multiplicative interactions (Table 4). In the joint effect analysis, the risk of VTE was significantly greater with high wGRS combined with high risk factors (OR of high BMI & high wGRS vs. low BMI & low wGRS = 3.44 [95% CI = 2.85 – 4.16], OR of low MET & high wGRS vs. high MET & low wGRS = 1.92 [95% CI = 1.60 – 2.29], OR of high sitting time & high wGRS vs. low sitting time & low wGRS = 1.64 [95% CI = 1.37 – 1.95]). Interaction effects assessed as departure from additivity were all positive (RERI > 0), indicating supra-additive interaction effects for all three risk factors (wGRS×BMI, wGRS×MET, and wGRS×sitting time). However, we only observed a statistically significant additive interaction for wGRS and BMI (RERI = 0.69 [95% CI = 0.01 – 1.36], p = 0.046). We did not observe any significant multiplicative interactions.

Table 4.

Joint and interaction effects of wGRS with BMI, MET-hour, and sitting time in the relation to VTE risk

| Pooled data (N= 6,024) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Joint association |

Additive Interaction |

Multiplicative Interaction |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| N case/control |

Adjusted¶ OR |

(95% CI) | RERI¶ | (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted¶ OR |

(95% CI) | ||

| BMI*wGRS | 0.69 | (0.01 – 1.36) | 0.046 | 1.02 | (0.78 – 1.33) | ||||

| BMI (Low) | wGRS (low) | 601/1,621 | 1.00 | (Reference) | |||||

| wGRS (high) | 895/1,608 | 1.49 | (1.31 – 1.70) | ||||||

| BMI (High) | wGRS (low) | 244/324 | 2.26 | (1.84 – 2.77) | |||||

| wGRS (high) | 394/337 | 3.44 | (2.85 – 4.16) | ||||||

| MET*wGRS | 0.09 | (−0.29 – 0.47) | 0.636 | 0.97 | (0.75 – 1.24) | ||||

| MET (High) | wGRS (low) | 593/1,464 | 1.00 | (Reference) | |||||

| wGRS (high) | 909/1,457 | 1.52 | (1.33 – 1.73) | ||||||

| MET (Low) | wGRS (low) | 252/481 | 1.31 | (1.08 – 1.59) | |||||

| wGRS (high) | 380/488 | 1.92 | (1.60 – 2.29) | ||||||

| Sitting time*wGRS | 0.09 | (−0.25 – 0.42) | 0.611 | 1.04 | (0.80 – 1.34) | ||||

| Sitting (Low) | wGRS (low) | 582/1,429 | 1.00 | (Reference) | |||||

| wGRS (high) | 886/1,460 | 1.49 | (1.30 – 1.70) | ||||||

| Sitting (High) | wGRS (low) | 263/516 | 1.06 | (0.88 – 1.29) | |||||

| wGRS (high) | 403/485 | 1.64 | (1.37 – 1.95) | ||||||

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction; BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task; wGRS, a standardized weighted genetic risk score

Low (L) and High(H) were differently defined for risk factors; BMI (L: 18.5– <30, H: 30+), MET(L: 1st quartile, H: 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles), sitting time (L: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd quartiles, H: 4th quartile), and wGRS (L: 1st and 2nd quartiles, H: 3rd and 4th quartiles)

Adjusting for two of the three risk factors (e.g. For BMI, MET and sitting time variables were adjusted.)

We observed heterogeneous effects of the wGRS-VTE association across risk factors (Table 5). VTE risk associated with wGRS was greater among individuals of higher BMI (OR for BMI 18.5 – < 25 = 1.37 [95% CI = 1.22 – 1.56], OR for BMI 25 – < 30 = 1.44 [95% CI = 1.24 – 1.66], and OR for BMI ≥ 30 = 1.56 [95% CI = 1.24 – 1.96]), although this trend was not significant (p for trend = 0.44). The wGRS odds ratios did not increase monotonically across decreasing MET-hour or increasing sitting-time quartiles; there were no significant differences in the wGRS odds ratios across quartiles of physical activity or sitting time. Neither categorical nor trend interactions between wGRS and each of the three risk factors were significant. When testing for interactions between continuous wGRS and continuous measures of BMI, physical activity, and sitting time, none of them showed a significant multiplicative interaction (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 5.

Adjusted association between wGRS and VTE risk stratified by risk factor groups and multiplicative interaction of wGRS and the risk factors

| Multiplicative interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| (Continuous) wGRS |

Categorical Interaction |

Trend Interaction |

||

|

|

||||

| Adjusted¶ OR | (95%CI) | P-value | Adjusted¶ OR (95% CI) | |

| Pooled data (N = 6,024) | ||||

| BMI | 0.44 | 1.02 (0.95 – 1.10) | ||

| 18.5 – < 25.0 | 1.37 | (1.22 – 1.56) | ||

| 25.0 – < 30.0 | 1.44 | (1.24 – 1.66) | ||

| 30.0 + | 1.56 | (1.24 – 1.96) | ||

| MET | 0.64 | 1.01 (0.96 – 1.06) | ||

| Quartile 1 | 1.27 | (1.07 – 1.52) | ||

| Quartile 2 | 1.38 | (1.12 – 1.71) | ||

| Quartile 3 | 1.49 | (1.21 – 1.83) | ||

| Quartile 4 | 1.40 | (1.15 – 1.71) | ||

| Sitting time | 0.61 | 1.03 (0.98 – 1.08) | ||

| Quartile 1 | 1.23 | (1.03 – 1.47) | ||

| Quartile 2 | 1.39 | (1.14 – 1.69) | ||

| Quartile 3 | 1.42 | (1.15 – 1.74) | ||

| Quartile 4 | 1.41 | (1.19 – 1.66) | ||

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; wGRS, a standardized weighted genetic risk score; BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task

Quartile cutoff of MET and Sitting time: 5.6/15.4/33.8 for MET, 17.0/32.0/54.0 for sitting time

Categorical interactions were examined with likelihood ratio test (df = 2 for BMI and df = 3 for MET and sitting time).

Trend interactions were examined with Wald test (df = 1).

Adjusting for two of the three risk factors (e.g. For BMI, MET and sitting time variables were adjusted.

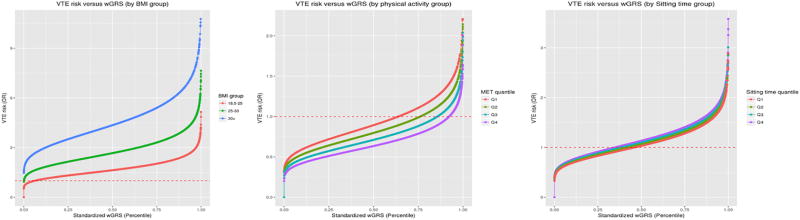

Figure 1 depicts the risk of VTE versus wGRS percentile by risk factor groups. Differences in the risk of VTE across BMI groups increased with increasing wGRS, consistent with supra-additive interactions on the absolute risk scale. Differences in risk across MET-hour and sitting time quartiles did not differ greatly as a function of wGRS. In SNP-specific analysis, one SNP (rs6025) in the F5 gene and three SNPs (rs2519093, rs495828, and rs687621) in the ABO gene were associated with increased risk of VTE across BMI groups (e.g. OR of rs6025 = 2.77 [BMI: 18.5 – < 25], 3.91 [BMI: 25 – < 30], and 5.61 [BMI: ≥ 30]) (Supplementary Table 5). The three ABO SNPs also showed supra-additive interaction effects with BMI (RERI for rs2519093 = 0.85 (p = 0.016), RERI for rs495828 = 1.25 (p = 0.0003), and RERI for rs687621 = 0.79 (p = 0.022)) (Supplementary Table 6) as well as significant multiplicative interactions with MET-hour (range of OR = 1.09 – 1.10).

Figure 1.

Adjusted association of wGRS and the risk of VTE, stratified by risk factor groups, in the pooled data (N= 6,024)

Abbreviation: wGRS, weighted genetic risk score; VTE, venous thromboembolism, OR, odds ratio; BMI, body mass index, MET, metabolic equivalent task.

DISCUSSION

We performed the first large study to assess interactions between physical activity, physical inactivity, BMI and genetic risk (measured by a wGRS) in relation to VTE risk. Previous research suggests that VTE risk is greatest when genetic predisposition is combined with an environmental risk factor (Heit et al., 2004; Rosendaal, 1999a, 1999b, 2005; Wolpin et al., 2010). However, few interactions have been explored in prospective cohort studies, and research has mostly focused on short-term risk factors such as trauma or surgery (Baba-Ahmed et al., 2007; Bedair, Berli, Gezer, Jacobs, & Della Valle, 2011; Ringwald, Berger, Adler, Kraus, & Pitto, 2009; van Boven, Vandenbroucke, Briet, & Rosendaal, 1999), and specific genetic risk factors such as Factor V Leiden (Ridker, Glynn, et al., 1997; Ridker, Hennekens, et al., 1997; van Boven et al., 1996; Vandenbroucke et al., 1994). Interactions between environmental risk factors and genetic risk scores have not been extensively studied with regards to VTE risk. In fact, only one previous study examined interactions of a genetic risk score for VTE with BMI and smoking (Crous-Bou, Harrington, & Kabrhel, 2016), though this study was smaller than our analysis and did not specifically assess additive interactions.

While we did not find evidence of interactions between the wGRS and physical activity or physical inactivity, the wGRS was positively associated with VTE risk and this was more pronounced among individuals with higher BMI. Furthermore, we observed a significant additive interaction between wGRS and BMI, demonstrating a synergetic effect of these factors on VTE risk. We also found increased risk of VTE by the combined effects of high BMI and VTE-associated individual SNPs (1 SNP in F5 gene and 3 SNPs in ABO gene). Particularly, rs6025 in F5 was associated with a 5.6-fold VTE risk increase among individuals with BMI ≥ 30, which is consistent to findings in a previous study (Juul, Tybjaerg-Hansen, Schnohr, & Nordestgaard, 2004). In their study, absolute risk of VTE increased with higher BMI (< 25, 25 – 30, > 30) and rs6025 genotype in a dose-response manner, even after adjusting for age and smoking.

In our study, little evidence on interaction between wGRS and physical activity or physical inactivity could be due to power. We have 80% power at the 0.05 level to detect multiplicative (additive) interaction with interaction OR > 1.40 (RERI > 1.47) for (binary) BMI, whereas we have the same power with interaction OR > 1.40 and 1.41 (RERI > 1.77 and 2.35) for (binary) physical activity and (binary) physical inactivity (Garcia-Closas & Lubin, 1999). This suggests that the study can detect clinically meaningful interaction effects but have less power to detect smaller effects, such as interactions of physical activity and inactivity. In addition, the strength of main effects could also affect the ability to detect gene-by-environment interactions (Kraft, Yen, Stram, Morrison, & Gauderman, 2007). As seen in Table 2 and 3, the main effects of wGRS and BMI showed consistently positive associations with the risk of VTE (e.g. maximum OR = 2.74), while MET-hours and sitting time showed relatively weak or no associations with VTE risk in our cohort with genetic data. Obesity is a well-known risk factor for VTE (Kabrhel et al., 2009; Parkin et al., 2012; Suchon et al., 2016; White, Gettner, Newman, Trauner, & Romano, 2000), while associations of physical activity and inactivity with VTE risk are less well established (Kahn, Shrier, & Kearon, 2008; van Stralen et al., 2008; van Stralen, Le Cessie, Rosendaal, & Doggen, 2007).

Strengths of this study include subjects from large prospective cohorts, efficient study design and analysis to increase power (i.e. matching study design and the use of a genetic risk score) and the use of a standard and objective measurement of physical activity (i.e. MET-hour per week). However, some limitations also need to be addressed. First, there is a potential for measurement error. To capture physical inactivity, we utilized different measures of sitting time across the three cohorts and we combined these different measures into a single measure of sitting time. If this process imparted measurement error, it could hamper our ability to identify interaction effects (Carroll & Carroll, 2006; Wong, Day, Luan, & Wareham, 2004). Moreover, unlike BMI or MET-hour, sitting time sometimes required data be carried forward more than 8 years (e.g. no data on sitting time between 1994 and 2002 in NHS), though this applied to very few cases (5.5% of a total cases). Hence, we cannot rule out the potential for measurement error, which would likely be non-differential misclassification that would bias results toward the null. In analyses, findings were not adjusted for multiple testing by three risk factors and two interaction approaches, so it is possible that our findings related to wGRS and BMI could be false positive. Our findings require replication in future studies. Additionally, we did not adjust for other potential confounders such as hormone use for women, smoking, or concurrent cancer status (Ashrani et al., 2016; El-Galaly et al., 2012; Gran et al., 2016; Martinelli et al., 2003; Severinsen et al., 2010; Vandenbroucke et al., 1994). Furthermore, we acknowledge the possibility that some of our VTE cases could have been associated with other disease states (e.g. cancer), which could also have gene-environment interactions that might confound our analysis. However, our three cohorts are large longitudinal cohorts where individuals develop a wide range of diseases over time, so it is unlikely that confounding by a specific disease state or health condition influenced our results. Lastly, our study population was comprised of largely white health professionals who might be more likely to have healthier lifestyles as compared to general population (e.g. more physically active in leisure time or lower BMI), which could limit generalizability. This should be considered when applying our findings to other populations.

In conclusion, we found evidence on a synergetic effect between a genetic risk score and high BMI on the risk of VTE. This suggests that intervention efforts to lower BMI could produce greater reductions in VTE risk among people with high genetic risk. Further studies are required to address whether such intervention is truly effective in preventing VTE in a high genetic-risk population. For physical activity and physical inactivity, further work is needed to better understand how these factors influence VTE risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the three cohorts, NHS, NHS2, and HPFS, for their contributions. This work was supported by grants R01 HL116854, UM1 CA186107, R01 HL034594, UM1 CA176726, R01 CA67262, UM1 CA167552, and T32 HL098048 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, Jr, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, Paffenbarger RS., Jr Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(1):71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrani AA, Gullerud RE, Petterson TM, Marks RS, Bailey KR, Heit JA. Risk factors for incident venous thromboembolism in active cancer patients: A population based case-control study. Thromb Res. 2016;139:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba-Ahmed M, Le Gal G, Couturaud F, Lacut K, Oger E, Leroyer C. High frequency of factor V Leiden in surgical patients with symptomatic venous thromboembolism despite prophylaxis. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97(2):171–175. doi:07020171 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggish AL, Wood MJ. Athlete's heart and cardiovascular care of the athlete: scientific and clinical update. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2723–2735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.981571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedair H, Berli M, Gezer S, Jacobs JJ, Della Valle CJ. Hematologic genetic testing in high-risk patients before knee arthroplasty: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):131–137. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1514-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite I, Healy B, Cameron L, Weatherall M, Beasley R. Venous thromboembolism risk associated with protracted work- and computer-related seated immobility: A case-control study. JRSM Open. 2016;7(8) doi: 10.1177/2054270416632670. 2054270416632670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RJ, Carroll RJ. Measurement error in nonlinear models : a modern perspective. 2. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology. 1996;7(1):81–86. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199601000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. The Nurses' Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(5):388–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous-Bou M, Harrington LB, Kabrhel C. Environmental and Genetic Risk Factors Associated with Venous Thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2016;42(8):808–820. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1592333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Forer L, Schonherr S, Sidore C, Locke AE, Kwong A, Fuchsberger C. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet. 2016;48(10):1284–1287. doi: 10.1038/ng.3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger S, Hron G, Bialonczyk C, Hirschl M, Minar E, Wagner O, Kyrle PA. Overweight, obesity, and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1678–1683. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Galaly TC, Kristensen SR, Overvad K, Steffensen R, Tjonneland A, Severinsen MT. Interaction between blood type, smoking and factor V Leiden mutation and risk of venous thromboembolism: a Danish case-cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(10):2191–2193. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Closas M, Lubin JH. Power and sample size calculations in case-control studies of gene-environment interactions: comments on different approaches. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(8):689–692. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain M, Chasman DI, de Haan H, Tang W, Lindstrom S, Weng LC, Morange PE. Meta-analysis of 65,734 individuals identifies TSPAN15 and SLC44A2 as two susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(4):532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain M, Saut N, Greliche N, Dina C, Lambert JC, Perret C, Morange PE. Genetics of venous thrombosis: insights from a new genome wide association study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gran OV, Smith EN, Braekkan SK, Jensvoll H, Solomon T, Hindberg K, Hansen JB. Joint effects of cancer and variants in the factor 5 gene on the risk of venous thromboembolism. Haematologica. 2016;101(9):1046–1053. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.147405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greliche N, Germain M, Lambert JC, Cohen W, Bertrand M, Dupuis AM, Tregouet DA. A genome-wide search for common SNP × SNP interactions on the risk of venous thrombosis. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke AA, Staib A, Gorlinger K, Perrey M, Dirkmann D, Kienbaum P. Whole blood coagulation and platelet activation in the athlete: a comparison of marathon, triathlon and long distance cycling. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15(2):59–65. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-15-2-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy B, Levin E, Perrin K, Weatherall M, Beasley R. Prolonged work- and computer-related seated immobility and risk of venous thromboembolism. J R Soc Med. 2010;103(11):447–454. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.100155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit JA. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(8):464–474. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit JA, Armasu SM, Asmann YW, Cunningham JM, Matsumoto ME, Petterson TM, De Andrade M. A genome-wide association study of venous thromboembolism identifies risk variants in chromosomes 1q24.2 and 9q. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(8):1521–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04810.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit JA, Phelps MA, Ward SA, Slusser JP, Petterson TM, De Andrade M. Familial segregation of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2(5):731–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7933.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd Predictors of survival after deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based, cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(5):445–453. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds DA, Buil A, Ziemek D, Martinez-Perez A, Malik R, Folkersen L, Sabater-Lleal M. Genome-wide association analysis of self-reported events in 6135 individuals and 252 827 controls identifies 8 loci associated with thrombosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(9):1867–1874. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Confidence interval estimation of interaction. Epidemiology. 1992;3(5):452–456. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RJ, Hopkins RJ, Hill S, Weatherall M, Van de Water N, Nowitz M, Beasley R. Frequency of venous thromboembolism in low to moderate risk long distance air travellers: the New Zealand Air Traveller's Thrombosis (NZATT) study. Lancet. 2003;362(9401):2039–2044. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull CM, Harris JA. Venous Thromboembolism in Physically Active People: Considerations for Risk Assessment, Mainstream Awareness and Future Research. Sports Med. 2015;45(10):1365–1372. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley WL, Comins SA, Green RM, Canizzaro J. Atraumatic subclavian vein thrombosis in a collegiate baseball player: a case report. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):198–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul K, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Schnohr P, Nordestgaard BG. Factor V Leiden and the risk for venous thromboembolism in the adult Danish population. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(5):330–337. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabrhel C, Varraso R, Goldhaber SZ, Rimm E, Camargo CA., Jr Physical inactivity and idiopathic pulmonary embolism in women: prospective study. BMJ. 2011;343:d3867. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabrhel C, Varraso R, Goldhaber SZ, Rimm EB, Camargo CA. Prospective study of BMI and the risk of pulmonary embolism in women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(11):2040–2046. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn SR, Shrier I, Kearon C. Physical activity in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Thromb Res. 2008;122(6):763–773. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klarin D, Emdin CA, Natarajan P, Conrad MF, Consortium I, Kathiresan S. Genetic Analysis of Venous Thromboembolism in UK Biobank Identifies the ZFPM2 Locus and Implicates Obesity as a Causal Risk Factor. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(2) doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft P, Yen YC, Stram DO, Morrison J, Gauderman WJ. Exploiting gene-environment interaction to detect genetic associations. Hum Hered. 2007;63(2):111–119. doi: 10.1159/000099183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapostolle F, Surget V, Borron SW, Desmaizieres M, Sordelet D, Lapandry C, Adnet F. Severe pulmonary embolism associated with air travel. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):779–783. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom S, Loomis S, Turman C, Huang H, Huang J, Aschard H, Kraft P. A comprehensive survey of genetic variation in 20,691 subjects from four large cohorts. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli I, Taioli E, Battaglioli T, Podda GM, Passamonti SM, Pedotti P, Mannucci PM. Risk of venous thromboembolism after air travel: interaction with thrombophilia and oral contraceptives. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2771–2774. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren E, Smith NL, Doggen CJ, Heckbert SR, Lemaitre RN. Body mass index and the risk of venous thrombosis among postmenopausal women. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(10):2273–2275. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin L, Sweetland S, Balkwill A, Green J, Reeves G, Beral V Million Women Study, C. Body mass index, surgery, and risk of venous thromboembolism in middle-aged women: a cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125(15):1897–1904. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DB, Kaufman JS. Estimation of the relative excess risk due to interaction and associated confidence bounds. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(6):756–760. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Glynn RJ, Miletich JP, Goldhaber SZ, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Age-specific incidence rates of venous thromboembolism among heterozygous carriers of factor V Leiden mutation. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(7):528–531. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-7-199704010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Selhub J, Miletich JP, Malinow MR, Stampfer MJ. Interrelation of hyperhomocyst(e)inemia, factor V Leiden, and risk of future venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 1997;95(7):1777–1782. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.7.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Rosner B, Stampfer MJ. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of coronary disease in men. Lancet. 1991;338(8765):464–468. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90542-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology. 1990;1(6):466–473. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwald J, Berger A, Adler W, Kraus C, Pitto RP. Genetic polymorphisms in venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after total hip arthroplasty: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6):1507–1515. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0498-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: a multicausal disease. Lancet. 1999a;353(9159):1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)10266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: prevalence and interaction of risk factors. Haemostasis. 1999b;29(Suppl S1):1–9. doi: 10.1159/000054106. doi:54106 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: the role of genes, environment, and behavior. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:1–12. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.1. doi:2005/1/1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinsen MT, Kristensen SR, Johnsen SP, Dethlefsen C, Tjonneland A, Overvad K. Anthropometry, body fat, and venous thromboembolism: a Danish follow-up study. Circulation. 2009;120(19):1850–1857. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinsen MT, Overvad K, Johnsen SP, Dethlefsen C, Madsen PH, Tjonneland A, Kristensen SR. Genetic susceptibility, smoking, obesity and risk of venous thromboembolism. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(2):273–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siniarski A, Wypasek E, Fijorek K, Gajos G, Undas A. Association between thrombophilia and seated immobility venous thromboembolism. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25(2):135–141. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e3283648163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souto JC, Almasy L, Borrell M, Blanco-Vaca F, Mateo J, Soria JM, Blangero J. Genetic susceptibility to thrombosis and its relationship to physiological risk factors: the GAIT study. Genetic Analysis of Idiopathic Thrombophilia. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(6):1452–1459. doi: 10.1086/316903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchon P, Al Frouh F, Henneuse A, Ibrahim M, Brunet D, Barthet MC, Morange PE. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in women under combined oral contraceptive. The PILl Genetic RIsk Monitoring (PILGRIM) Study. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(1):135–142. doi: 10.1160/TH15-01-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Teichert M, Chasman DI, Heit JA, Morange PE, Li G, Smith NL. A genome-wide association study for venous thromboembolism: the extended cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(5):512–521. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao K, Davenport M. Deep venous thromboembolism in a triathlete. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(3):351–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tregouet DA, Heath S, Saut N, Biron-Andreani C, Schved JF, Pernod G, Morange PE. Common susceptibility alleles are unlikely to contribute as strongly as the FV and ABO loci to VTE risk: results from a GWAS approach. Blood. 2009;113(21):5298–5303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boven HH, Reitsma PH, Rosendaal FR, Bayston TA, Chowdhury V, Bauer KA, Lane DA. Factor V Leiden (FV R506Q) in families with inherited antithrombin deficiency. Thromb Haemost. 1996;75(3):417–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boven HH, Vandenbroucke JP, Briet E, Rosendaal FR. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions determine risk of thrombosis in families with inherited antithrombin deficiency. Blood. 1999;94(8):2590–2594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stralen KJ, Doggen CJ, Lumley T, Cushman M, Folsom AR, Psaty BM, Heckbert SR. The relationship between exercise and risk of venous thrombosis in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(3):517–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stralen KJ, Le Cessie S, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. Regular sports activities decrease the risk of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(11):2186–2192. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke JP, Koster T, Briet E, Reitsma PH, Bertina RM, Rosendaal FR. Increased risk of venous thrombosis in oral-contraceptive users who are carriers of factor V Leiden mutation. Lancet. 1994;344(8935):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varraso R, Kabrhel C, Goldhaber SZ, Rimm EB, Camargo CA., Jr Prospective study of diet and venous thromboembolism in US women and men. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(2):114–126. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendelboe AM, Campbell J, McCumber M, Bratzler D, Ding K, Beckman M, Raskob G. The design and implementation of a new surveillance system for venous thromboembolism using combined active and passive methods. Am Heart J. 2015;170(3):447–454. e418. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J, Perrin K, Aldington S, Weatherall M, Beasley R. A case-control study of seated immobility at work as a risk factor for venous thromboembolism. J R Soc Med. 2008;101(5):237–243. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.070366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RH, Gettner S, Newman JM, Trauner KB, Romano PS. Predictors of rehospitalization for symptomatic venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(24):1758–1764. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Corsano KA, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(5):991–999. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpin BM, Kabrhel C, Varraso R, Kraft P, Rimm EB, Goldhaber SZ, Fuchs CS. Prospective study of ABO blood type and the risk of pulmonary embolism in two large cohort studies. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(5):962–971. doi: 10.1160/th10-05-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MY, Day NE, Luan JA, Wareham NJ. Estimation of magnitude in gene-environment interactions in the presence of measurement error. Stat Med. 2004;23(6):987–998. doi: 10.1002/sim.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoller B, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. A sibling based design to quantify genetic and shared environmental effects of venous thromboembolism in Sweden. Thromb Res. 2017;149:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.