Abstract

Members of the transglutaminase family catalyze the formation of isopeptide bonds between a polypeptide bound glutamine and a low molecular weight amine (e.g., spermidine) or the ε-amino group of a polypeptide bound lysine. Transglutaminase 2 (TG2), a prominent member of this family, is unique because in addition to being a transamidating enzyme, it exhibits numerous other activities. As a result, TG2 plays a role in many physiological processes, and its function is highly cell type specific and relies upon a number of factors, including conformation, cellular compartment location, and local concentrations of Ca2+ and guanine nucleotides. TG2 is the most abundant transglutaminase in the central nervous system (CNS) and plays a pivotal role in the CNS injury response. How TG2 affects the cell in response to an insult is strikingly different in astrocytes and neurons. In neurons TG2 supports survival. Overexpression of TG2 in primary neurons protects against oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD)-induced cell death and in vivo results in a reduction in infarct volume subsequent to a stroke. Knockdown of TG2 in primary neurons results in a loss of viability. In contrast, deletion of TG2 from astrocytes results in increased survival following OGD and improved ability to protect neurons from injury. Here a brief overview of TG2 is provided, followed by a discussion of the role of TG2 in transcriptional regulation, cellular dynamics and cell death. The differing roles TG2 plays in neurons and astrocytes are highlighted and compared to how TG2 functions in other cell types.

Introduction

Transglutaminase 2 (TG2), also known as tissue transglutaminase, is a unique member of the transglutaminase family as it is ubiquitously expressed, catalyzes a number of different reactions and is involved in mediating numerous molecular processes. In addition to its transamidating activity, TG2 has been shown to function as a GTPase, a protein disulphide isomerase and a molecular scaffold (Gundemir et al. 2012). The function that TG2 takes on relies upon a number of variables including cell type, intracellular localization and extracellular environment. In addition, the mulifunctionality of TG2 is mediated by its different domains and conformations.

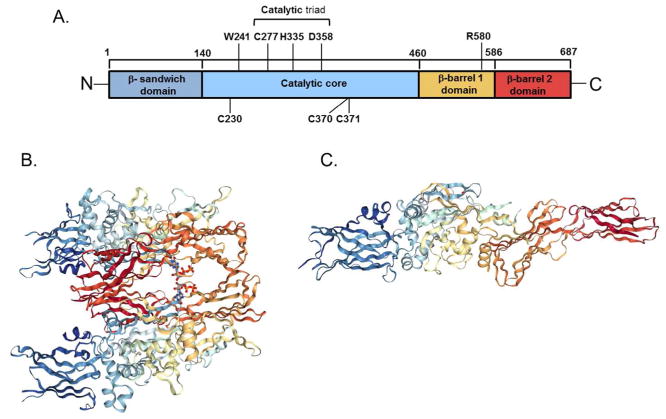

TG2 contains 4 domains; an N-terminal β sandwich domain, a catalytic domain, and 2 C-terminal β barrel domains (Lorand and Graham 2003). The transamidating activity is mediated by the catalytic domain and Ca2+ binding is required for activation which facilitates a more open conformation of the protein, while guanine di- and triphosphate (GDP and GTP, respectively) binding promote a more closed conformation and inhibition of transamidating activity (Achyuthan and Greenberg 1987; Liu et al. 2002; Pinkas et al. 2007). The structural differences between the closed and open conformations are quite remarkable. When the predicted structure of TG2 in its fully extended conformation is aligned with TG2 in its closed, GTP/GDP bound conformation the C-terminal residues are displaced by up to 120 Å (Figure 1). In response to this large conformational shift in tertiary structure, there is also a change in secondary structure which results in backbone rearrangements that further extend the catalytic active site (Pinkas et al. 2007).

Figure 1.

Domains (A), closed (B) and open (C) structures of human transglutaminase 2 (TG2) (A)The catalytic triad is mediates the transamidating activity in a Ca2+ dependent manner. Six Ca2+ binding sites have been identified in the catalytic core. W241 is essential for the stabilization of the intermediate state of the transamidation. R580 is required for efficient GTP/GDP binding. C230, C370 and C371 act as redox sensors maintaining TG2 in an inactive state in oxidizing conditions. (B) Closed, guanine nucleotide bound form of TG2 as a dimer (Liu et al. 2002). Bound GDP is shown as a ball stick model between the first and second β-barrels (PDB ID code 1KV3). (C) Open, transamidating active form of TG2 (Pinkas et al. 2007) (PDB ID code 2Q3Z).

As indicated above, Ca2+ binding results in TG2 taking on the open, transamidating active conformation. The catalytic domain contains 6 putative Ca2+ binding domains, 5 of which have been shown to be functional. It was found that each of these sites contains loops with negative charges to accommodate the binding of the Ca2+ ion. All 5 of these sites play a role in the catalytic activity of TG2 (Kiraly et al. 2009). Binding of Ca2+ to these sites forces TG2 into an open conformation that allows substrates access to the catalytic triad (Cys277, His335, and Asp358), which are positioned to allow the flow of electrons required for the transamidation reaction to occur (Murthy et al. 2002; Pedersen et al. 1994). Trp241 residue stabilizes the intermediate state of the transamidating reaction, and mutating it results in a complete loss of function (Murthy et al. 2002). TG2 also has a GTPase function, and GTP/GDP binding inhibits the transamidating function of the catalytic core. The binding of GTP masks Arg580, a destabilizing switch residue in the first β-barrel required for GTP binding, which allows the protein to take on its closed, inactive conformation (Begg et al. 2006). Thus, the transamidating activity of TG2 is activated by Ca2+, and inhibited by GDP and GTP. Under normal physiological conditions, it would be expected that the closed inactive form of TG2 would dominate in the cytosol, as intracellular concentrations of GTP surpass what is required for binding, and Ca2+ concentrations are insufficient for binding to occur (Eckert et al. 2014; Gundemir et al. 2012). The reverse is expected for the extracellular space where Ca2+ concentrations are much higher and GTP/GDP concentrations are low and thus an open conformation would predominate with TG2 being active as a transamidating enzyme. This, however, is not the case. TG2 is predominantly inactive in the extracellular space, until it is activated by a stimulus such as inflammatory mediators. This is due to a triad of cysteine residues (Cys230, Cys370 and Cys371) that act as redox sensor for TG2 (Stamnaes et al. 2010). Under conditions of oxidation, Cys230 facilitates the formation of a disulfide bridge between Cys370 and Cys371, preventing the transamidating activity of the protein. Cys230 is unique to TG2 amongst the transglutaminase proteins, making this redox mediated inactivation unique to TG2 (Stamnaes et al. 2010) (Figure 1). Therefore, there are a variety of conditions that affect the conformation of TG2, and hence the functions that it will be able to perform. The most prominent factors are the local concentrations of activating Ca2+, concentrations of inactivating GDP/GTP, and the redox conditions of the environment.

TG2 as a transcriptional regulator

TG2 has been well-established as a modulator of gene expression. Indeed, the functioning of numerous transcription factors have been shown to be regulated by TG2 (Eckert et al. 2014; Gundemir et al. 2012). However given the focus of this review, here we will just focus on signaling pathways in neural systems that have been reported to be modulated by TG2.

Signaling by cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) is increased by TG2, albeit indirectly. In ovarian cancer cells TG2 facilitates CREB-mediated gene expression. The data suggest that this is due toTG2 transamidating protein phosphatase 2a-α, a phosphatase that is known to inactivate CREB, targeting it for degradation. This allows CREB to remain phosphorylated and active, increasing the transcription of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) (Satpathy et al. 2009). TG2 also increases cAMP levels in human astrocytoma and rat glioma cells by modifying and activating adenylyl cyclase 8 in a transamidating dependent manner.

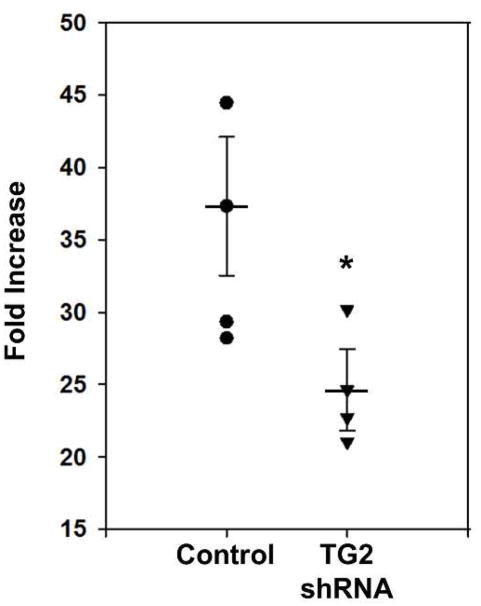

This in turn increases the activity of CREB in these cells (Obara et al. 2013). Similar findings were reported in an earlier study using human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. In these cells, overexpression of wild type TG2, but not a C277S mutant that lacks transamidating activity and the ability to efficiently bind GTP (Begg et al. 2006; Gundemir and Johnson 2009), significantly increases forskolin-induced Cre activity relative to cells transfected with vector only. Like in the glioma cells, this enhancement of CREB phosphorylation and Cre activity is due to TG2 significantly potentiating adenylyl cyclase activity and cAMP production in a transamidating dependent manner (Tucholski and Johnson 2003). Intriguingly, knockdown of TG2 in rat primary neurons with TG2 shRNA results in an attenuation of Cre activity in response to treatment with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) (Figure 2). The fact that TG2 increases CREB activation in neural and non-neural cells may suggest that this is a conserved regulatory function of TG2.

Figure 2.

Depletion of TG2 in neurons attenuates Cre luciferase reporter activity. Primary rat cortical neurons were transduced with TG2 shRNA as indicated. Five days after transduction all neurons were transfected with a Cre luciferase reporter and a promoterless null Renilla construct. Two days later the neurons were treated with IBMX or vehicle overnight followed by measurement of luciferase and renilla activity. The luciferase measurements were normalized to its Renilla measurement. Results are shown as fold increase relative to vehicle-treated measurements and expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, n= 3 (Y. Nuzbrokh and S. Gundemir, unpublished data).

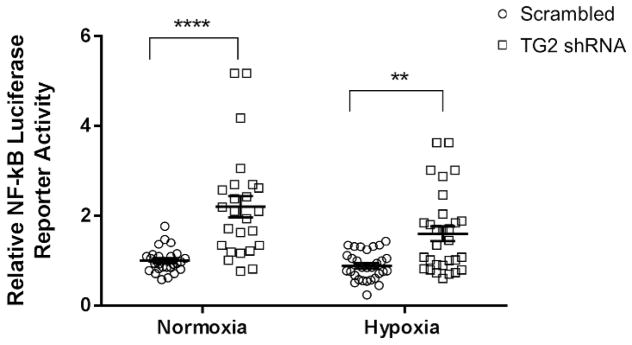

A substantial number of studies have shown that TG2 regulates the activity of the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), although how TG2 affects NF-κB signaling varies significantly depending on the cell type. In the cancer cell models that have been examined, TG2 has been shown to activate NF-κB (Agnihotri et al. 2013; Eckert et al. 2014; Mann et al. 2006). Overexpression of TG2 in HEK cells also increased NF-κB activity (Jang et al. 2010), and in immortalized activated murine microglia (BV-2 cells)TG2 activates NF-κB in response to lipopolysaccharides (LPS) treatment, and this resulted in increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Lee et al. 2004). Interestingly, there is data suggesting that TG2 potentiates renal ischemic injury by increasing NF-κB activation (Kim et al. 2010). It appears that TG2 increases NF-κB activity by inducing the polymerization of the inhibitory IκBα which would require TG2 to be active as a transamidating enzyme (Lee et al. 2004) and/or by binding to IκBα and facilitating its degradation by a non-proteasomal dependent pathway in a transamidation independent manner (Kumar and Mehta 2012). As an illustration of the latter, overexpression of either wild type TG2 or the C277S mutant in breast cancer cells activated NF-κB (Kumar and Mehta 2012). Overall, these data indicate that TG2 upregulates NF-κB activity in cancer cells, immortalized cell lines and primary non-neural cells. In contrast to these findings, depletion or deletion of TG2 in primary astrocytes results in a significant and robust increase in NF-κB activity. Intriguingly, treatment of wild type astrocytes with the irreversible TG2 inhibitor VA4, which forces and maintains TG2 in an open conformation, resulted in a significant decrease in NF-κB activity. These findings suggest that TG2 may be acting as an adaptor to inhibit NF-κB activation, and this function is optimal when TG2 is in the open conformation (Feola et al. 2017). Similar to what was observed in astrocytes; knockdown of TG2 in primary neurons significantly increases NF-κB activity (Figure 3), although the mechanisms involved have not been defined. These findings strongly indicate that the molecular roles that TG2 plays in the nervous system are likely fundamentally different from how it functions in non-neural systems.

Figure 3.

The depletion of TG2 increases NF-κB luciferase reporter activity. Primary rat cortical neurons were transduced with TG2 shRNA or scrambled control. Five days after transduction the neurons were transfected with an NF-κB luciferase reporter and a promoterless null Renilla construct. Two days later the neurons were exposed to hypoxia (0.1% O2) or normoxia for 14 hours. After hypoxia the luciferase and Renilla expression were measured. The luciferase measurements were normalized to its Renilla measurement. Final results were normalized to control measurements. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. n= 5 biological replicates with 5–6 separate wells for each condition.

Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) signaling is likewise regulated by TG2. In breast cancer cells overexpression of TG2 results in a constitutive upregulation of HIF1α, increased HRE activation and thus increased expression of HIF responsive genes (Kumar et al. 2014). This increase in HIF signaling is proposed to be due to TG2 dependent activation of NF-κB signaling which increases the expression of HIF1α and a gene expression profile that supports the Warburg effect (Kumar et al. 2014). In contrast to what was observed in breast cancer cells, in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells and primary neurons TG2 significantly attenuates hypoxia-induced HIF activation, and this inhibition is not dependent on its transamidating activity or GTP binding (Filiano et al. 2008; Gundemir et al. 2013). Further, it was demonstrated that in neuroblastoma cells and neurons TG2 binds to HIF1β; however, this interaction could be separated from its ability to suppress HIF signaling. Nonetheless, nuclear localization of TG2 was required for the suppressive effect on HIF signaling and it was recruited to the HRE site in the enolase promoter. Intriguingly, in this same study overexpression of TG2 with a nuclear export signal (NES) to reduce nuclear levels, increased hypoxic-induced HRE activity in MCF-7 cells, while expression of wild type or nuclear localization sequence (NLS) tagged TG2 did not. This finding may in part explain the different findings in cancer cells and neurons (Gundemir et al. 2013).

The relationship between TG2 localization, activation state and cell survival/death

Depending on the cell type TG2 can localize to the extracellular matrix (ECM), cell surface, cytoplasm, mitochondria and in the nucleus (Gundemir et al. 2012). Under normal conditions, between ~5–10% of endogenous TG2 localizes to the nucleus (Lesort et al. 1998; Park et al. 2010), and in the nucleus of human neuroblastoma cells TG2 is found primarily in the chromatin fraction (Lesort et al. 1998). The subcellular localization of TG2, as well as its conformational and activity state, likely plays a major role in determining how it affects cell signaling events and thus survival. In tumor cells and cancer stem cells, TG2 expression levels are increased and this promotes cell survival (Eckert et al. 2015). Further, the ability of TG2 to support the survival of cancer seems to require that it be in a GTP bound closed conformation (Eckert et al. 2015). In neurons, TG2 has differential effects on survival, which likely depends on its activation state. In a mouse model where human TG2 was overexpressed in neurons, increased neuronal cell death was observed subsequent to kainic acid induced seizures. In this model, TG2 takes on a more open conformation with increased transamidating activity due to significantly elevated intraneuronal Ca2+ levels (Tucholski et al. 2006). However, in the same mouse model of human TG2 overexpression in neurons, there was a significant decrease in infarct volume following permanent middle cerebral ligation (MCAL) (Filiano et al. 2010). In primary neurons, overexpression of wild type TG2 or the C277S mutant (which is transamidating inactive and deficient in GDP/GTP binding (Begg et al. 2006; Gundemir and Johnson 2009)), protected against oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD)-induced cell death(Filiano et al. 2008).. Further, in SH-SY5Y cells, knocking down TG2 resulted in a significant increase in OGD-induced cell death (Gundemir et al. 2013). When TG2-R580A, which does not bind guanine nucleotides and thus exhibits a more open conformation and a high basal transamidating activity (TG2-R580K exhibits the same characteristics (Begg et al. 2006)), was expressed in immortalized striatal cells, increased cell death was observed following OGD compared to cells expressing vector only. However, if TG2-R580A was targeted to the nucleus the detrimental effects were significantly attenuated (Colak et al. 2011). These findings demonstrate that in neurons, and neuronally derived cells, the localization and activation state of TG2 plays a critically important role in determining cell survival outcomes.

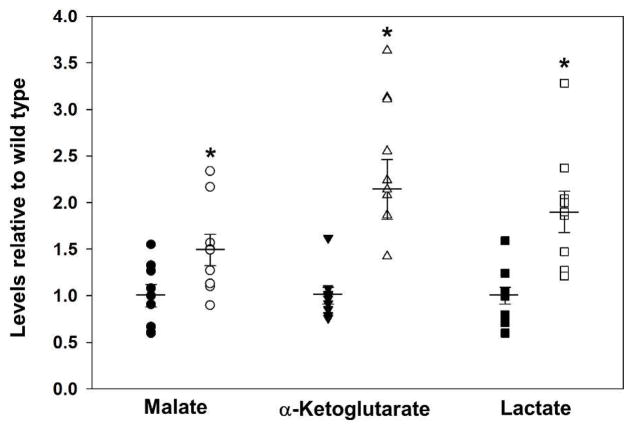

In contrast to neurons, the role that TG2 plays in astrocytes to regulate cell death/survival is very different. Given the initial finding that overexpression of human TG2 in neurons significantly decreased infarct volume following MCAL (Filiano et al. 2010), it was reasoned that complete deletion of TG2 should worsen outcomes. In fact just the opposite was true. Infarct volumes were significantly smaller in complete TG2 knockout (TG2−/−) mice following MCAL (Colak and Johnson 2012). Upon further investigation it was found that, as expected, TG2−/− neurons were more susceptible to OGD-induced cell death than wild type neurons, but the opposite was true for the TG2−/− astrocytes, as they were more resistant to OGD-induced cell death than wild type astrocytes. When astrocytes were co-cultured with neurons it was found that TG2−/− astrocytes were able to protect wild type or TG2−/− neurons from OGD-induced cell death to a significantly greater extent than wild type astrocytes (Colak and Johnson 2012). In further studies it was also found that knocking down TG2 in astrocytes with TG2 shRNA also significantly increased their viability following OGD (Feola et al. 2017) and their ability to protect neurons (Monteagudo et al., manuscript in preparation). While further investigation is needed, one possible explanation for this phenomenon could be that TG2 knockout in astrocytes could result in changes in the metabolic pathways that produce products that are released to protect neurons. In support of this hypothesis it was found that TG2−/− astrocytes produce higher levels of malate, lactate, and α-ketoglutarate than wild type astrocytes subsequent to OGD (Figure 4). It is noteworthy that astrocytes normally release lactate as a result of anaerobic metabolism, and this can be taken up by neurons through channels called monocarboxylate transporters (Falkowska et al. 2015). Once lactate has been taken up by the neuron, it is converted to pyruvate by lactate dehydrogenase, which is then used as a substrate for oxidative phosphorylation. Taken together, it would seem that TG2 activity in neurons and astrocytes may play a role in regulating energy metabolism, benefiting neurons which rely heavily on aerobic metabolism and seemingly hindering astrocytes which more readily utilize anaerobic metabolism. In support of this hypothesis, one study found that cells lacking TG2 were more sensitive to the glycolytic inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose than cells expressing the protein, indicating a shift toward glycolytic metabolism (Rossin et al. 2012).

Figure 4.

Deletion of transglutaminase 2 (TG2) in astrocytes significant increases the levels of lactate, malate and α-ketoglutarate after ischemic stress. Primary astrocytes from wild type (closed symbols) and TG2−/− (open symbols) mice were exposed to 90 minutes of oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD, 0.1% O2) followed by 24 hrs of reperfusion. Cells were snap frozen and metabolites were extracted with 80% methanol. Extracted metabolites were analyzed using reverse phase chromatography with an ion-pairing reagent in a Shimadzu HPLC coupled to a Thermo Quantum triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Nadtochiy et al. 2015). Data are expressed relative to wild type astrocytes. Results are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, n= 8. (A. Monteagudo, unpublished data).

It is also important to point out that the effect of TG2 on astrocyte survival and NF-κB signaling are separable events. Treatment of wild type astrocytes with the irreversible inhibitor (VA4) that maintains TG2 in an open conformation significantly improved astrocyte survival following OGD, similar to what was observed when TG2 was knocked down. This is in contrast to what was observed with NF-κB signaling. Knockdown or knockout of TG2 in astrocytes significantly increased NF-κB activity, while treatment with VA4 resulted in a significant inhibition (Feola et al. 2017).

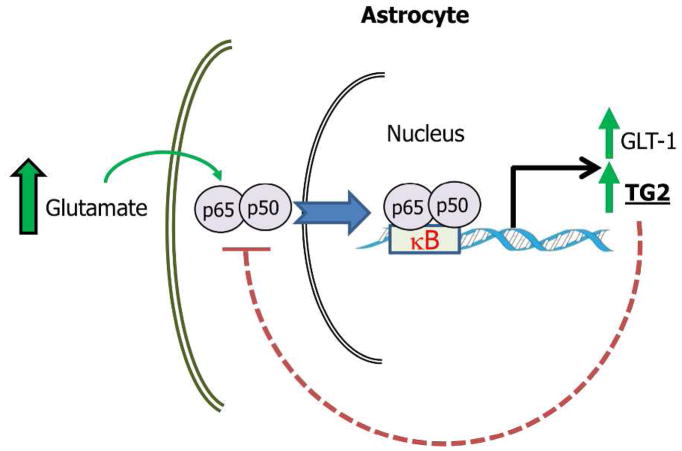

While the effect of TG2 on NF-κB signaling can be separated from its effect on astrocyte survival, it may play a role in the ability of astrocytes to promote survival of neurons in the context of excitotoxicity. In excitotoxicity there is excessive excitation of glutamatergic neurons leading to an inappropriate release of glutamate into the synapse. A primary defense against excitotoxicity is the uptake of glutamate by astrocytes, and glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1) plays a major role in mediating this process. One study found that GLT-1 expression in astrocytes that are co-cultured with neurons is dependent upon NF-κB signaling in the astrocytes (Ghosh et al. 2011). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that treatment of primary rat astrocytes with glutamate increased TG2 expression (Campisi et al. 2003), concurrent with increased nuclear localization of NF-κB subunits, as well as increased binding of these subunits to the promoter of TG2 (Caccamo et al. 2005). Taken together, it can be suggested that excessive glutamate may result in an increase of NF-κB nuclear localization and activity, which in turn increases the expression of GLT-1 in astrocytes. This would allow astrocytes to remove the excess glutamate from the synapse and protect neurons from excitotoxicity. However, since TG2 inhibits the activity of NF-κB in astrocytes (Feola et al. 2017) this could reduce the ability of astrocytes to protect neurons from excitotoxicity (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hypothetical model illustrating how TG2 mediated suppression of NF-κB signaling in astrocytes could compromise the ability of astrocytes to protect against neurons against excitotoxicity. In pathological conditions where there is excessive excitation of glutamatergic neurons and release of glutamate the primary protective response is uptake of glutamate by astrocytes and GLT-1 plays a major role in this process. GLT-1 expression in astrocytes is mediated by NF-κB signaling (Ghosh et al. 2011). Glutamate treatment of astrocytes results in increased nuclear localization of NF-κB subunits, as well as increased binding of these subunits to the promoter of TG2 (Caccamo et al. 2005) which can increase TG2 expression (Mirza et al. 1997). Given that in astrocytes TG2 represses NF-κB activity (Feola et al. 2017) this could lead to decreased GLT-1 expression which would result in decreased glutamate uptake.

Clearly further studies are needed to understand why TG2 differentially affects survival in neurons and astrocytes, although one clue may be that in response to stress the localization patterns of TG2 differ significantly. In hypoxic conditions the levels of TG2 in the nucleus of neurons increase significantly, while in astrocytes there is a significant decrease in nuclear TG2 (Yunes-Medina et al. 2017). This data provides a conceptual framework in which nuclear TG2 is protective while cytosolic TG2 is detrimental to survival, due to increased transamidating activity resulting from the open conformation assumed by TG2. This observation may provide a clue as to why TG2 differentially impacts stress-induced cell death in neurons and astrocytes.

The role of TG2 in cellular structural dynamics

In many different cell types TG2 increases adhesion, migration and cellular spreading (Eckert et al. 2014), including astrocytes and neurons. There is good evidence that TG2 facilitates the interaction of astrocytes with the ECM and supports astrocyte migration, and in nervous system injury models could contribute to the formation of glial scars (van Strien et al. 2011b; van Strien et al. 2011c). Treatment of astrocytes with pro-inflammatory cytokines increased expression, externalization and activity of TG2 which plays a pivotal role in stimulating the formation of focal adhesions and mediating astrocyte migration (van Strien et al. 2011b). Deletion of TG2 or inhibition with irreversible inhibitor VA4 significantly reduced the motility of cultured astrocytes. Further, the migration defect in TG2−/− astrocytes could only be rescued with wild type TG2; neither the R580A mutant (that does not bind GTP/GDP and exhibits increased transamidating activity) nor the W241A mutant (which is transamidating inactive) was able to restore motility (Monteagudo et al. 2017). These findings are in agreement with an earlier study that showed the transglutaminase inhibitor KCC009 also inhibited astrocyte migration (van Strien et al. 2011b). These data suggest that both transamidation and guanine nucleotide binding are essential for TG2 to facilitate astrocyte migration. It is also interesting to note that migration could be rescued in TG2−/− astrocyte with the addition of TGFβ1, an inflammatory cytokine that is also known to induce reactive astrogliosis (Monteagudo et al. 2017). This would suggest that TG2 activates migration in a pathway that is independent of the TGFβ receptor, perhaps by inducing migration through MAP kinase-mediated reorganization of actin (Zarubin and Han 2005). Additionally, TG2 has been shown to interact with fibronectin in the ECM (van Strien et al. 2011b), resulting in the activation of β1 integrins, a family of proteins involved in the regulation of the cellular adherence and cytoskeletal rearrangement required for migration (Telci et al. 2008). TG2 similarly plays a role in facilitating remodeling in neuronal cells. Overexpression of wild type TG2, but not the C277S mutant, resulted in spontaneous neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y cells in low serum (Tucholski et al. 2001), and differentiation of wild type SH-SY5Y cells in the presence of a TG2 inhibitor resulted in significant inhibition of neurite outgrowth (Song et al. 2013). Further, in primary neurons, knocking down TG2 results in a pronounced decrease in neurite length (Yunes-Medina et al. 2018). Intriguingly TG2 also appears to play a significant role in stabilization of axonal microtubules by catalyzing the incorporation of polyamines into tubulin. Indeed, the levels of cold-stable microtubules were significantly reduced in young TG2−/− mouse brain and spinal cord relative to the levels in age-matched wild type mice (Song et al. 2013). These data suggest that in both astrocytes and neurons the roles that TG2 plays in mediating cellular structural dynamics require a catalytically active protein and that similar mechanisms may be involved.

TG2 supports neuronal survival

The fact that nuclear localization of TG2 is key to its ability to play a protective role, and that it primarily localizes to the chromatin fraction, suggest that transcriptional regulation by TG2 is likely of fundamental importance. An unbiased approach using RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) on neurons transduced with TG2 shRNA or a scrambled (scr) version yielded interesting results (Yunes-Medina et al. 2018). Intriguingly, simply depleting TG2 resulted in a loss of neuronal viability. To ensure that any changes observed in gene expression were not simply due to the loss of viability; RNA-seq was carried out on samples from transduced neurons collected at a time point prior to any loss of viability. Differentially expressed gene analysis revealed that the expression of 86 genes was changed due to knocking down TG2, with the majority (59) of these being upregulated. In addition, enriched pathway analysis revealed that the genes differentially expressed in neurons after TG2 knockdown were predominantly involved in cell signaling, ECM function and cytoskeletal integrity pathways (Yunes-Medina et al. 2018). To further understand how TG2 regulates neuronal gene expression, chromatin-immunoprecipitation was performed in neurons with TG2 overexpression. Using this unbiased approach, a signature DNA motif was found to be enriched in the TG2 immunoprecipitated genomic DNA. Intriguingly this motif mapped to a region proximate to the gene Ctss (cathepsin s), and also the gene Ctsk (cathepsin k, also known as cathepsin x), although slightly more distal. Further, knockdown of TG2 resulted in an increase in these genes prior to loss of viability (Ji et al, manuscript submitted). Interestingly, increases in cathepsin s have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease relevant neurodegenerative processes (Lemere et al. 1995; Munger et al. 1995; Nubling et al. 2017) and inhibition of cathepsin k facilitates neurite outgrowth (Obermajer et al. 2009). These and other findings suggest that in neurons, TG2 plays a direct role in the mediating gene transcription by regulating the repression of genes involved in cytoskeletal rearrangement and cell-matrix interactions, and thus neurite extension and remodeling. The expression of genes in a healthy cell is dependent on a balance between activation and repression. It can be speculated that knockdown of TG2 in neurons disrupts this balance and, given the genes that are affected, the result is unhealthy neurites which in turn negatively impact neuron survival. In astrocytes knockdown of TG2 does not result in loss of viability (Feola et al. 2017); however, their ability to extend their filopodia and migrate is significantly reduced (Monteagudo et al. 2017). Although there are similarities between the processes involved in neurite and filopodia dynamics, it is likely that TG2 differentially affects these cellular events in neurons and astrocytes. For example, TG2 is externalized by astrocytes, but not neurons (Van Strien et al. 2011a; van Strien et al. 2011b; Yunes-Medina et al. 2017), and the interaction of TG2 with the ECM plays an important role in modifying the ability of astrocytes to extend their filopodia and migrate (Van Strien et al. 2011a; van Strien et al. 2011b).

Conclusions and future directions

In summary, TG2 plays key, but often quite different, roles in neurons and astrocytes (see Table 1). Indeed, knocking down TG2 in neurons compromises viability, while in astrocytes knocking down TG2 has no significant effect on viability in control conditions and significantly increases survival after an ischemic insult. Interestingly, in vivo the negative effects of TG2 activity in astrocytes seem dominant over the positive effects in neurons. This is demonstrated in the cases of ischemic stroke, where global TG2 deletion results in decreased stroke volumes following an MCAL model despite there being increased OGD-induced cell death in TG2−/− neurons when they are in culture. Further, in a co-culture paradigm TG2−/− astrocytes increased neuronal survival compared to wild type astrocytes after OGD, regardless of whether or not the neurons contained TG2 themselves (Colak and Johnson 2012). This would suggest that the potentially detrimental role of TG2 in astrocytes plays a greater role in the response to CNS ischemic insult than the protective role in neurons, basically in the intact CNS “less is better” in the case of TG2 following an injury. This also might hold true for other conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases. For example, when TG2−/− mice were crossed with mice expressing mutant huntingtin protein neuronal cell death was decreased (Mastroberardino et al. 2002). This was originally attributed to TG2 playing a detrimental role in neurons, however more recent data suggests it could be due an enhanced beneficial effect of the TG2 deficient astrocytes.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the differential effects of transglutaminase 2 (TG2) in neurons and astrocytes

| Effects | Neurons | Astrocytes |

|---|---|---|

| NF-κB activity | Down regulates through an unknown mechanism | Down regulates; requires TG2 in an open conformation |

| Subcellular localization in response to ischemic/hypoxic stress and outcomes | Nuclear levels increase; regulates transcription predominantly by facilitating repression. Effects are not dependent on transamidating activity. | Nuclear levels decrease; mainly functions as a transamidating enzyme in the cytosol or ECM. |

| Viability following ischemia in vitro | Protects independent of transamidating activity and GTP binding | Detrimental to survival; inhibition of transamidating activity or knockdown increases viability |

| In vivo stroke model: Infarct volumes | Overexpression in only neurons significantly decreases stroke volumes | Knock down decreases stroke volumes and dominates over effect in neurons |

| Cell Migration and cytoskeleton dynamics | Supports neurite outgrowth; may depend on transamidating activity | Facilitates motility and migration; transamidating activity dependent |

| Overall Effects | Primarily beneficial effects for neurons, supports survival in stressful conditions | Negatively effects survival and ability to protect neurons in response to injury or stress. |

Overall it is clear that the functions of TG2 are cell type and situation specific, and generalizing the function of TG2 based on findings in a given cell type and circumstance often cannot be done. Of critical importance going forward is to understand what governs the differential localization of TG2 in neurons and astrocytes, as well as the cell type specific interactors. Additionally, it is crucial to determine the role of conformation and activity state in astrocytes and neurons in control and stress conditions, and how this impacts outcomes. TG2 is truly a multifunctional protein that modulates numerous cellular processes. Delineating the underlying mechanisms that are responsible for the seeming paradoxical roles of TG2 in astrocytes and neurons will provide a better understanding of the response of the nervous system to insults and may provide new targets for improved treatments for ischemic stroke and other related injuries.

Significance.

Transglutaminase 2 (TG2) is a protein that plays key roles in cell death and survival processes. TG2 is expressed in both neurons and astrocytes in the central nervous systems (CNS); however how TG2 affects survival following injury is extraordinarily different in these two cell types. In neurons TG2 supports survival subsequent to ischemic injury and TG2 knockdown results in loss of neuronal viability. The opposite is true in astrocytes; deletion of TG2 increases survival after ischemia. Here we discuss the differing roles of TG2 in neurons and astrocytes, as well as underlying molecular mechanisms that may contribute to these differences.

Acknowledgments

This work from the authors’ laboratory was supported NIH grants NS065825 and NS084572 and a grant through the Schmitt Program in Integrative Neuroscience (SPIN) (University of Rochester).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

Role of Authors

Conceptualization, GVWJ; Writing-original draft, GVWJ, BRQ; Writing-review and editing, GVWJ, BRQ, LY-M; Visualization, GVWJ, BRQ, LY-M.

References

- Achyuthan KE, Greenberg CS. Identification of a guanosine triphosphate-binding site on guinea pig liver transglutaminase. Role of GTP and calcium ions in modulating activity. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(4):1901–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri N, Kumar S, Mehta K. Tissue transglutaminase as a central mediator in inflammation-induced progression of breast cancer. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2013;15(1):202. doi: 10.1186/bcr3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg GE, Carrington L, Stokes PH, Matthews JM, Wouters MA, Husain A, Lorand L, Iismaa SE, Graham RM. Mechanism of allosteric regulation of transglutaminase 2 by GTP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(52):19683–19688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609283103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo D, Campisi A, Curro M, Aguennouz M, Li Volti G, Avola R, Ientile R. Nuclear factor-kappab activation is associated with glutamate-evoked tissue transglutaminase up-regulation in primary astrocyte cultures. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82(6):858–865. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi A, Caccamo D, Raciti G, Cannavo G, Macaione V, Curro M, Macaione S, Vanella A, Ientile R. Glutamate-induced increases in transglutaminase activity in primary cultures of astroglial cells. Brain research. 2003;978(1–2):24–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colak G, Johnson GV. Complete transglutaminase 2 ablation results in reduced stroke volumes and astrocytes that exhibit increased survival in response to ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45(3):1042–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colak G, Keillor JW, Johnson GV. Cytosolic guanine nucledotide binding deficient form of transglutaminase 2 (R580a) potentiates cell death in oxygen glucose deprivation. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert RL, Fisher ML, Grun D, Adhikary G, Xu W, Kerr C. Transglutaminase is a tumor cell and cancer stem cell survival factor. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2015;54(10):947–958. doi: 10.1002/mc.22375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert RL, Kaartinen MT, Nurminskaya M, Belkin AM, Colak G, Johnson GV, Mehta K. Transglutaminase regulation of cell function. Physiological reviews. 2014;94(2):383–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkowska A, Gutowska I, Goschorska M, Nowacki P, Chlubek D, Baranowska-Bosiacka I. Energy Metabolism of the Brain, Including the Cooperation between Astrocytes and Neurons, Especially in the Context of Glycogen Metabolism. International journal of molecular sciences. 2015;16(11):25959–25981. doi: 10.3390/ijms161125939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feola J, Barton A, Akbar A, Keillor J, Johnson GVW. Transglutaminase 2 Modulation of NF-kappaB Signaling in Astrocytes is Independent of its Ability to Mediate Astrocytic Viability in Ischemic Injury. Brain research. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiano AJ, Bailey CD, Tucholski J, Gundemir S, Johnson GV. Transglutaminase 2 protects against ischemic insult, interacts with HIF1beta, and attenuates HIF1 signaling. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2008;22(8):2662–2675. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-097709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiano AJ, Tucholski J, Dolan PJ, Colak G, Johnson GV. Transglutaminase 2 protects against ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39(3):334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M, Yang Y, Rothstein JD, Robinson MB. Nuclear factor-kappaB contributes to neuron-dependent induction of glutamate transporter-1 expression in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2011;31(25):9159–9169. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0302-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundemir S, Colak G, Feola J, Blouin R, Johnson GV. Transglutaminase 2 facilitates or ameliorates HIF signaling and ischemic cell death depending on its conformation and localization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundemir S, Colak G, Tucholski J, Johnson GV. Transglutaminase 2: a molecular Swiss army knife. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823(2):406–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundemir S, Johnson GV. Intracellular localization and conformational state of transglutaminase 2: implications for cell death. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang GY, Jeon JH, Cho SY, Shin DM, Kim CW, Jeong EM, Bae HC, Kim TW, Lee SH, Choi Y, Lee DS, Park SC, Kim IG. Transglutaminase 2 suppresses apoptosis by modulating caspase 3 and NF-kappaB activity in hypoxic tumor cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(3):356–367. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DS, Kim B, Tahk H, Kim DH, Ahn ER, Choi C, Jeon Y, Park SY, Lee H, Oh SH, Kim SY. Transglutaminase 2 gene ablation protects against renal ischemic injury by blocking constant NF-kappaB activation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;403(3–4):479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly R, Csosz E, Kurtan T, Antus S, Szigeti K, Simon-Vecsei Z, Korponay-Szabo IR, Keresztessy Z, Fesus L. Functional significance of five noncanonical Ca2+-binding sites of human transglutaminase 2 characterized by site-directed mutagenesis. The FEBS journal. 2009;276(23):7083–7096. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Donti TR, Agnihotri N, Mehta K. Transglutaminase 2 reprogramming of glucose metabolism in mammary epithelial cells via activation of inflammatory signaling pathways. International journal of cancer. 2014;134(12):2798–2807. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Mehta K. Tissue transglutaminase constitutively activates HIF-1alpha promoter and nuclear factor-kappaB via a non-canonical pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim YS, Choi DH, Bang MS, Han TR, Joh TH, Kim SY. Transglutaminase 2 induces nuclear factor-kappaB activation via a novel pathway in BV-2 microglia. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(51):53725–53735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemere CA, Munger JS, Shi GP, Natkin L, Haass C, Chapman HA, Selkoe DJ. The lysosomal cysteine protease, cathepsin S, is increased in Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome brain. An immunocytochemical study. The American journal of pathology. 1995;146(4):848–860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesort M, Attanavanich K, Zhang J, Johnson GV. Distinct nuclear localization and activity of tissue transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(20):11991–11994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.11991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Cerione RA, Clardy J. Structural basis for the guanine nucleotide-binding activity of tissue transglutaminase and its regulation of transamidation activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(5):2743–2747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042454899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorand L, Graham RM. Transglutaminases: crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2003;4(2):140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrm1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann AP, Verma A, Sethi G, Manavathi B, Wang H, Fok JY, Kunnumakkara AB, Kumar R, Aggarwal BB, Mehta K. Overexpression of tissue transglutaminase leads to constitutive activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer cells: delineation of a novel pathway. Cancer research. 2006;66(17):8788–8795. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteagudo A, Ji C, Akbar A, Keillor JW, Johnson GV. Inhibition or ablation of transglutaminase 2 impairs astrocyte migration. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2017;482(4):942–947. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger JS, Haass C, Lemere CA, Shi GP, Wong WS, Teplow DB, Selkoe DJ, Chapman HA. Lysosomal processing of amyloid precursor protein to A beta peptides: a distinct role for cathepsin S. The Biochemical journal. 1995;311(Pt 1):299–305. doi: 10.1042/bj3110299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy SN, Iismaa S, Begg G, Freymann DM, Graham RM, Lorand L. Conserved tryptophan in the core domain of transglutaminase is essential for catalytic activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(5):2738–2742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052715799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nubling G, Schuberth M, Feldmer K, Giese A, Holdt LM, Teupser D, Lorenzl S. Cathepsin S increases tau oligomer formation through limited cleavage, but only IL-6, not cathespin S serum levels correlate with disease severity in the neurodegenerative tauopathy progressive supranuclear palsy. Experimental brain research. 2017;235(8):2407–2412. doi: 10.1007/s00221-017-4978-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara Y, Yanagihata Y, Abe T, Dafik L, Ishii K, Nakahata N. Galpha(h)/transglutaminase-2 activity is required for maximal activation of adenylylcyclase 8 in human and rat glioma cells. Cellular signalling. 2013;25(3):589–597. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermajer N, Doljak B, Jamnik P, Fonovic UP, Kos J. Cathepsin X cleaves the C-terminal dipeptide of alpha- and gamma-enolase and impairs survival and neuritogenesis of neuronal cells. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2009;41(8–9):1685–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Choi SS, Ha KS. Transglutaminase 2: a multi-functional protein in multiple subcellular compartments. Amino acids. 2010;39(3):619–631. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0500-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen LC, Yee VC, Bishop PD, Le Trong I, Teller DC, Stenkamp RE. Transglutaminase factor XIII uses proteinase-like catalytic triad to crosslink macromolecules. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society. 1994;3(7):1131–1135. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkas DM, Strop P, Brunger AT, Khosla C. Transglutaminase 2 undergoes a large conformational change upon activation. PLoS biology. 2007;5(12):e327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin F, D’Eletto M, Macdonald D, Farrace MG, Piacentini M. TG2 transamidating activity acts as a reostat controlling the interplay between apoptosis and autophagy. Amino acids. 2012;42(5):1793–1802. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0899-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpathy M, Shao M, Emerson R, Donner DB, Matei D. Tissue transglutaminase regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 in ovarian cancer by modulating cAMP-response element-binding protein activity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(23):15390–15399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808331200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Kirkpatrick LL, Schilling AB, Helseth DL, Chabot N, Keillor JW, Johnson GV, Brady ST. Transglutaminase and polyamination of tubulin: posttranslational modification for stabilizing axonal microtubules. Neuron. 2013;78(1):109–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamnaes J, Pinkas DM, Fleckenstein B, Khosla C, Sollid LM. Redox regulation of transglutaminase 2 activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(33):25402–25409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.097162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telci D, Wang Z, Li X, Verderio EA, Humphries MJ, Baccarini M, Basaga H, Griffin M. Fibronectin-tissue transglutaminase matrix rescues RGD-impaired cell adhesion through syndecan-4 and beta1 integrin co-signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(30):20937–20947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801763200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucholski J, Johnson GV. Tissue transglutaminase directly regulates adenylyl cyclase resulting in enhanced cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(29):26838–26843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucholski J, Lesort M, Johnson GV. Tissue transglutaminase is essential for neurite outgrowth in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neuroscience. 2001;102(2):481–491. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucholski J, Roth KA, Johnson GV. Tissue transglutaminase overexpression in the brain potentiates calcium-induced hippocampal damage. Journal of neurochemistry. 2006;97(2):582–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien ME, Baron W, Bakker EN, Bauer J, Bol JG, Breve JJ, Binnekade R, Van Der Laarse WJ, Drukarch B, Van Dam AM. Tissue transglutaminase activity is involved in the differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells into myelin-forming oligodendrocytes during CNS remyelination. Glia. 2011a;59(11):1622–1634. doi: 10.1002/glia.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Strien ME, Breve JJ, Fratantoni S, Schreurs MW, Bol JG, Jongenelen CA, Drukarch B, van Dam AM. Astrocyte-derived tissue transglutaminase interacts with fibronectin: a role in astrocyte adhesion and migration? PLoS One. 2011b;6(9):e25037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Strien ME, Drukarch B, Bol JG, van der Valk P, van Horssen J, Gerritsen WH, Breve JJ, van Dam AM. Appearance of tissue transglutaminase in astrocytes in multiple sclerosis lesions: a role in cell adhesion and migration? Brain Pathol. 2011c;21(1):44–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunes-Medina L, Feola J, Johnson GVW. Subcellular localization patterns of transglutaminase 2 in astrocytes and neurons are differentially altered by hypoxia. Neuroreport. 2017;28:1208–1214. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunes-Medina L, Paciorkowski A, Nuzbrokh Y, Johnson GVW. Depletion of transglutaminase 2 in neurons alters expression of extracellular matrix and signal transduction genes and compromises cell viability. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2018;86:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarubin T, Han J. Activation and signaling of the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Cell research. 2005;15(1):11–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]