Abstract

HIV infection may increase risk of postpartum infection and infection-related mortality. We hypothesized that postpartum infection incidence and attributable mortality in Mbarara, Uganda would be higher in HIV-infected than HIV-uninfected women. We performed a prospective cohort study of 4,231 women presenting to a regional referral hospital in 2015 for delivery or postpartum care. All febrile or hypothermic women, and a subset of randomly selected normothermic women were followed during hospitalization and with 6-week postpartum phone interviews. The primary outcome was in-hospital postpartum infection. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital complications (mortality, re-operation, intensive care unit transfer, need for imaging or blood transfusion) and 6-week mortality. We performed multivariable regression analyses to estimate adjusted differences in each outcome by HIV serostatus. Mean age was 25.2 years and 481 participants (11%) were HIV-infected. Median CD4+ count was 487 (IQR 325, 696) cells/mm3, and 90% of HIV-infected women (193/215 selected for in-depth survey) were on antiretroviral therapy. Overall, 5% (205/4231) of women developed fever or hypothermia. Cumulative in-hospital postpartum infection incidence was 2.0% and did not differ by HIV status (aOR 1.4, 95% CI 0.6–3.3, P=0.49). However, more HIV-infected women developed postpartum complications (4.4% vs. 1.2%, P=0.001). In-hospital mortality was rare (2/1,768, 0.1%), and remained so at 6 weeks (4/1526, 0.3%), without differences by HIV serostatus (P=1.0 and 0.31, respectively). For women in rural Uganda with high rates of antiretroviral therapy coverage, HIV infection did not predict postpartum infection or mortality, but was associated with increased risk of postpartum complications.

Keywords: HIV, antiretroviral, Africa, infection, puerperal sepsis, pregnancy

Introduction

In the pre-antiretroviral therapy era (ART), HIV increased morbidity and mortality among pregnant and postpartum women.(Maiques-Montesinos, Cervera-Sanchez, Bellver-Pradas, Abad-Carrascosa, & Serra-Serra, 1999; McIntyre, 2003; Moodley & Moodley, 2005; Zvandasara et al., 2006) HIV-associated adverse maternal outcomes disproportionately affected sub-Saharan Africa, where maternal mortality is high and where 90% of HIV-infected women live.(McIntyre, 2003; WHO, 2004) Though prospective data on risk and severity of HIV-associated peripartum complications in sub-Saharan Africa has been lacking, pre- and early-ART era studies performed elsewhere demonstrated that HIV increased maternal morbidity and mortality.(Calvert & Ronsmans, 2013; McIntyre, 2003) A large study in North America found HIV-infected women had twice the risk of postpartum endometritis and postpartum blood transfusion, five times the risk of maternal sepsis, and eight times the risk of maternal death, compared to HIV-uninfected women.(Louis et al., 2007) HIV-associated maternal mortality has largely been attributed to non-obstetric causes, including infections.(Black, Brooke, & Chersich, 2009; Fawcus, van Coeverden de Groot, & Isaacs, 2005; Garenne, McCaa, & Nacro, 2008; Khan, Pillay, Moodley, & Connolly, 2001; Nduati et al., 2001; Ronsmans & Graham, 2006; Zvandasara et al., 2006) Untreated HIV increases risk(Semprini et al., 1995) and severity(Kesson & Sorrell, 1993; van den Akker, de Vroome, Mwagomba, Ford, & van Roosmalen, 2011) of pregnancy-related infections, especially endometritis.(Calvert & Ronsmans, 2013; Louis et al., 2007; Semprini et al., 1995)

Since the advent of ART, improvements in HIV-related morbidity and mortality have been documented worldwide.("Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013," 2015; Reniers et al., 2014) A multisite North American study demonstrated a decline in postpartum morbidity incidence in HIV-infected women from 17% in 1990 to 11% in 1998, a finding supported by other studies.(Kourtis et al., 2014; Read et al., 2001; Reshi & Lone, 2010) However, few large-scale prospective studies of HIV-associated maternal morbidity and mortality have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa, and even fewer since the dramatic ART scale-up over the last decade.(Calvert & Ronsmans, 2013; WHO, 2017) Some recent studies in sub-Saharan Africa have demonstrated persistence of excess morbidity and mortality in peripartum HIV-infected women.(Matthews et al., 2013; Ngonzi et al., 2016) One study of maternal mortality in Mbarara, Uganda found puerperal sepsis was the most common cause of death (31% of deaths), and that 35% of women who died of puerperal sepsis were HIV-infected, compared to 16% HIV infection prevalence in women dying of other causes.(Ngonzi et al., 2016) Understanding whether HIV remains a significant risk factor for pregnancy-related infections, maternal morbidity and mortality in the era of widespread ART has important public health implications for management of pregnant and postpartum HIV-infected women. Such knowledge could impact choice of ART regimens in pregnancy, monitoring of HIV-infected women during the peripartum period, and decisions about peripartum antibiotic prophylaxis and treatment.

We sought to determine whether HIV remains an independent risk factor for postpartum infection, morbidity and mortality in Mbarara, Uganda, where maternal ART coverage is >90%.(Matthews et al., 2016; UNAIDS, 2016b) To do so, we enrolled a large prospective cohort of pregnant and postpartum women presenting in labor for delivery or within the 42-day postpartum period, screened them for postpartum infection, and performed clinical and microbiological evaluation of febrile and hypothermic women. We hypothesized that postpartum infection incidence and attributable mortality in Mbarara, Uganda would be significantly higher in HIV-infected than HIV-uninfected women.

Materials and Methods

Study site

Participants were recruited from Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) in Mbarara, Uganda between March and October, 2015. MRRH is an approximately 300-bed academic hospital affiliated with Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST). It is the largest teaching and referral hospital for Western Uganda, with a catchment of nine million people living in a predominantly rural, agrarian setting. In 2011, it was estimated that 69% of Ugandans have ever been tested for HIV, and 47% know their HIV status.(Staveteig, Croft, Kampa, & Head, 2017) Regional HIV prevalence is estimated at 9% among women, 74% receive HIV counseling and testing during routine antenatal care,("Uganda AIDS Indicator Survey 2011," 2012) 57% of treatment-eligible Ugandans access ART, and >95% of pregnant women received effective medications to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission.(UNAIDS, 2016a, 2016b) The World Health Organization recommends ‘Option B+’ triple drug ART for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women, a strategy adopted in Uganda from 2010 onwards, which led to higher CD4 counts and earlier ART initiation for pregnant women in HIV programs at the treatment clinic in Mbarara.(Miller, Muyindike, Matthews, Kanyesigye, & Siedner, 2017) HIV prevalence among HIV-exposed infants tested was 3.5% in 2016.("The Uganda HIV and AIDS Country Progress Report June 2015–June 2016," 2016) Women are educated on ART use through adherence counseling as recommended by the Ugandan Ministry of Health,("Consolidated Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of HIV in Uganda," 2016) and it is standard-of-care to treat all HIV-infected pregnant women with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) prophylaxis against opportunistic infections.("Consolidated Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of HIV in Uganda," 2016) Average ART adherence among women living with HIV in Mbarara was 92% in pregnancy, 88% postpartum, and HIV viral suppression was achieved at 93% of pregnancy and 89% of postpartum visits.(Matthews et al., 2016) There are over 1,000 facilities in Uganda offering ART, including the Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital HIV (ISS) Clinic.("The HIV and AIDS Uganda Country Progress Report 2014," 2015) ISS offers comprehensive HIV care services, including ART, at no cost to patients. ART funding is provided through the Ugandan Ministry of Health with support from the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the Global Fund, and the Family Treatment Fund.(Geng et al., 2010; UNAIDS, 2016b) According to local standards of care, women hospitalized for delivery and postpartum care undergo daily and as-needed vital signs monitoring. Vaginal deliveries are generally attended by midwives, while cesarean deliveries are conducted by obstetricians and obstetricians-in-training. Current hospital practice is for women delivering by cesarean to receive a single dose of peri-procedural antibiotic prophylaxis (ampicillin or ceftriaxone), usually given within 30 minutes of skin incision. In addition, after cesarean delivery, women are treated with combination intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole for three days, followed by five days of oral cefixime. Antibiotics are not routinely given to women delivering vaginally.

Participant recruitment and clinical data collection

All women presenting to MRRH maternity ward in labor for delivery or for care within 42 days postpartum between March and October 2015 were approached for enrollment, including women hospitalized for antenatal care who subsequently labored. All study participants provided written informed consent. Potential participants were excluded if they did not speak English or Runyankole, if they declined consent, or were incapacitated and next-of-kin declined surrogate consent. Enrolled women were followed by a team of trained research nurses measuring vital signs, including oral temperature, approximately every eight hours after delivery until the participant was discharged.

HIV status determination and CD4 testing

All participants were asked to self-report HIV infection status. Participants self-reporting HIV-negative or untested status were re-tested if their last HIV test was >6 months prior. Those testing positive underwent confirmatory testing according to local guidelines. HIV-infected participants reported the date and result of their last CD4+ T-cell count (CD4 count). If the participant’s last CD4 count was >6 months prior, or the result was unavailable, peripheral blood was sent for CD4 testing.

Sample collection and microbiology testing

Participants with fever >38.0 °C or hypothermia < 36.0 °C were tested for malaria using SD Bioline Malaria Ag Pf/Pan rapid diagnostic test (Standard Diagnostics, Gyeonggi, Korea), provided a clean-catch urine sample, and had peripheral blood drawn aseptically into Becton Dickinson (BD) BACTEC (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, USA) bottles. Two aerobic, two anaerobic and one mycobacterial blood culture were transported to the Epicentre Mbarara Research Centre microbiology laboratory adjacent to MRRH. Microbiology and urinalysis testing was performed as described previously.(Bebell et al., 2017)

Power and sample size

Sample size was calculated as the number of participants needed to detect a doubling of infection risk from 5% to 10% comparing HIV-uninfected to HIV-infected women, calculated at 3,500. Risk of infection was based on estimates that 10% of women develop peripartum fever (Smaill & Grivell, 2014), and 45–50% of febrile women are diagnosed with a pelvic or obstetric infection.(Gilstrap & Cunningham, 1979; van den Akker et al., 2011) We therefore estimated risk of postpartum infection among HIV-uninfected women to be 5%, similar to published estimates of postpartum sepsis incidence sub-Saharan Africa.(Seale, Mwaniki, Newton, & Berkley, 2009) An additional 731 participants were enrolled to achieve enrollment targets for a nested sub-study.

Data collection

Febrile or hypothermic participants and a random selection of normothermic participants underwent additional in-depth data collection including a structured face-to-face interview and chart review at hospital discharge. We randomly selected 1,708 normothermic participants as a comparison group to achieve at least a 4:1 ratio of normothermic:febrile/hypothermic participants, maximizing power to detect differences between groups.

Defining outcomes

Febrile and hypothermic participants were evaluated at the time of abnormal temperature using structured physical exam and symptom questionnaire developed by study investigators and administered by trained study nurses. Postpartum endometritis (puerperal sepsis) was defined using the WHO technical working group 1992 definition as infection of the genital tract in which two or more of the following were present: pelvic pain, fever >38.0 °C, abnormal vaginal discharge, and delay in the rate of reduction of the size of the uterus <2cm/day.(Dolea & Stein, 2003) Urinary tract infection (UTI) was defined by urinalysis positive for leukocyte esterase or nitrite and urine culture growing one or two pathogens of ≥105 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter (mL) (uncomplicated UTI),(Wilson & Gaido, 2004) ≥103 CFU/mL in the presence of nausea, vomiting or flank pain (pyelonephritis),(Wilson & Gaido, 2004) or ≥103 CFU/mL in a participant with a urinary catheter in place or removed within the previous 48 hours (catheter-associated UTI).(Hooton et al., 2010) Bloodstream infection (bacteremia) was defined as the growth of a potential pathogen in one or more blood culture bottles. Diagnosis of superficial cesarean surgical site infection was abstracted from chart review. Our primary study outcome was confirmed postpartum infection, a composite outcome including bloodstream infection, urinary tract infection, or clinical endometritis diagnosed by our research staff using the definitions above. Cesarean surgical site infection was not confirmed by research staff and not included in the composite primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital complications, readmission during the postpartum period, and early neonatal death.

Data entry and statistical analysis

Questionnaires and laboratory results were entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database.(Harris et al., 2009) Summary statistics were used to characterize the cohort. Demographic characteristics and outcomes were compared between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected participants using Chi squared or Fisher’s exact analysis for categorical variables and student’s t-test or Wilcoxon Rank-Sum for continuous variables. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with the primary composite postpartum infection outcome. Predictor variables selected for inclusion in the model included published risk factors for postpartum infection: HIV infection, age, parity, employment, distance of residence from hospital, number of vaginal exams in labor, obstructed labor diagnosis, delivery mode, and reported duration of labor.(Bako, Audu, Lawan, & Umar, 2012; Janni et al., 2002; Lapinsky, 2013; Maharaj, 2007a, 2007b; van Dillen, Zwart, Schutte, & van Roosmalen, 2010; Wandabwa et al., 2011; Yokoe et al., 2001) Additional variables were included if, on bivariate analysis, they demonstrated a correlation with the outcome with a P-value <0.1. All variables with P-values<0.05 in the final model were considered significant independent predictors of the outcome. If patients withdrew their consent, no further sample or data collection was performed, but existing data were included in the final analysis. All analyses were performed using Stata software (Version 12.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Ethics

All enrolled women provided written informed consent prior to data collection. Participants <18 years of age were enrolled as emancipated minors based on pregnancy status. The study was approved by the institutional ethics review boards at MUST (08/10–14), Partners Healthcare (2014P002725/MGH) and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (HS/1729).

Results

Enrollment and demographics

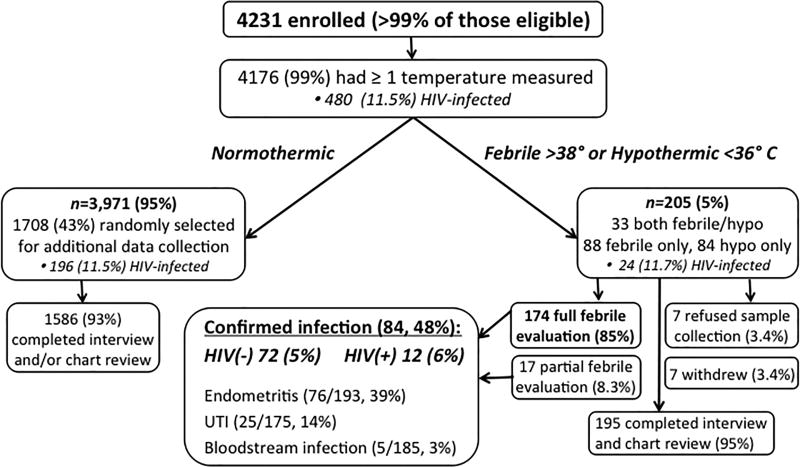

Of all eligible women presenting to MRRH for care during the study period, over 99% (4,235) were enrolled, and four withdrew before data collection was performed, leaving 4,231 participants with data for analysis. Of the normothermic cohort, 1,708 women were randomly selected for additional in-depth data collection, and 1,567 (92%) had both chart review and interview data. An additional 19 participants had either chart review or interview data, and all 1,586 participants with either chart review or interview data were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Mean cohort age was 25.2 years (standard deviation (SD) 5.5 years), 667 (38%) were primiparous and 875 (50%) delivered by cesarean. HIV-infected participants were older, more likely to reside in the same district as the hospital, and report malaria prophylaxis or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) receipt during pregnancy than HIV-uninfected women (all P<0.05, see Table 1). HIV-infected women were less likely to be married than HIV-uninfected women, but more likely to be multiparous (P<0.01, see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort enrollment, outcomes and follow-up.

Table 1.

Demographics, pregnancy and obstetric history, and post-delivery care, comparing HIV-uninfected to HIV-infected participants.

| Characteristic | Number (%) HIV-uninfected n=1570 |

Number (%) HIV-infected n=215§ |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Age category | 0.04 | ||

| ≤19 | 217 (14) | 19 (9) | |

| 20–34 | 1195 (78) | 167 (80) | |

| >34 | 116 (8) | 23 (11) | |

| Residence in Mbarara municipality | 623 (43) | 105 (52) | 0.01 |

| Married | 1457 (94) | 174 (83) | <0.001 |

| Formally employed | 603 (39) | 76 (36) | 0.39 |

| Median household monthly income (UGxa) | 150,000 | 100,000 | 0.08 |

| Referred from another health facility | 208 (14) | 22 (10) | 0.22 |

| PREGNANCY & OBSTETRIC HISTORY | |||

| Admitted in labor | 1487 (96) | 203 (96) | 0.96 |

| Attended ≥ 4 ANCb visits | 1091 (71) | 149 (71) | 0.85 |

| Received malaria prophylaxis (or TMP/SMXc) | 1405 (91) | 208 (99) | <0.001 |

| Syphilis or STId in pregnancy | 45 (3) | 11 (5) | 0.07 |

| Urinary tract infection in pregnancy | 48 (3) | 2 (1) | 0.08 |

| Malaria in pregnancy | 159 (10) | 13 (6) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes, cardiac or renal dis. in pregnancy | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.46 |

| Total number of pregnancies | 0.002 | ||

| 1 | 608 (39) | 57 (27) | |

| 2–4 | 745 (48) | 127 (60) | |

| ≥5 | 191 (12) | 27 (13) | |

| Gestational age at delivery | 0.32 | ||

| Miscarriage (<28 weeks) | 1 (0.07) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Preterm delivery (28–37 weeks) | 138 (10) | 22 (11) | |

| Term (37–42 weeks) | 1176 (82) | 155 (79) | |

| Post-term (>42 weeks) | 121 (8) | 18 (9) | |

| ≥5 self-reported vaginal exams | 159 (11) | 20 (11) | 0.90 |

| Cesarean delivery mode | 770 (51) | 99 (48) | 0.45 |

| Estimated duration of labor (mean hours (SDe)) | 17 (16) | 15 (14) | 0.37 |

| Singleton pregnancy | 1492 (97) | 204 (98) | 0.60 |

| POST-DELIVERY CARE | |||

| Peri-Cesarean antibiotic prophylaxis prescribed | 759 (99) | 96 (99) | 0.54 |

| Days in hospital (mean days (SD)) | 2.5 (2.5) | 2.9 (5.0) | 0.054 |

| Urinary catheter placed | 816 (53) | 95 (45) | 0.03 |

| Catheter days (mean days (SD)) | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.06 |

UGx: Uganda Shillings;

ANC: antenatal clinic;

TMP/SMX: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole;

STI: sexually transmitted infection;

SD: standard deviation.

Tests of association between characteristics and HIV infection were performed using Chi squared, Fisher’s exact, and Student’s t-tests, where appropriate.

A total of 456 HIV-infected women were normothermic. However, only 196/456 (43%) were randomly selected for in-depth data collection on ART and TMP/SMX use.

HIV infection, CD4 results and ART

Overall, 481/4,231 (11.4%) of participants were HIV-infected, and 92/4,231 (1.7%) were missing data on HIV status. Of 481 HIV-infected participants, 480 had one or more temperature measurements, 258 (54%) self-reported CD4 count results, and 83/258 (32%) of these were confirmed by chart review. Another 174/481 (36%) of participants had CD4 testing performed as part of the study. Overall, CD4 count results were available for 442/481 (92%) of HIV-infected participants. Median CD4 count was 487 (interquartile range (IQR) 325, 696) cells/mm3 and did not differ between normothermic and febrile/hypothermic participants (P=0.96), though normothermic participants were significantly more likely to be taking TMP/SMX prophylaxis (98 vs. 87%, P=0.002, see Table 2). Of 215/481 (45%) participants randomly selected for in-depth data collection, 193/215 (90%) reported current treatment with combination ART, 11/215 (5%) reported no current ART, and 11/215 (5%) were missing data on this variable. The most commonly reported regimen was combination emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/efavirenz (Atripla) in 69/215 (32%), while 104/215 (48%) did not know the name of their ART. Of 215 HIV-infected women, 198 (92%) reported current TMP/SMX prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, 6/215 (3%) were not taking TMP/SMX, and 11 (5%) were missing data on this variable.

Table 2.

Characteristics of HIV-infected participants, by fever status.

| Characteristic | Number (%) normothermic n=456§ |

Number (%) febrile or hypothermic n=24 |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV care | 0.10 | ||

| ISSa clinic at MRRHb | 95 (21.1) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Another HIV clinic or health center | 354 (78.5) | 20 (83.3) | |

| No current HIV care | 2 (0.4) | 1 (4.2) | |

| CD4c category, cells/mm3 | 0.96 | ||

| <200 | 38 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) | |

| 200–349 | 76 (18.1) | 5 (22.7) | |

| 350–500 | 101 (24.1) | 5 (22.7) | |

| >500 | 204 (48.7) | 10 (45.5) | |

| CD4 count (median (IQRd)), cells/mm3 | 487 (328, 699) | 487 (302, 657) | 0.69 |

| Number months since last CD4 (mean (SDe)) | 2.1 (2.7) | 1.4 (2.2) | 0.22 |

| Current ARTf (n=220)§ | 173 (95.6) | 20 (87.0) | 0.09 |

| Current TMP/SMXg prophylaxis(n=220)§ | 178 (98.3) | 20 (87.0) | 0.002 |

ISS: Immune Suppression Syndrome;

MRRH: Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital;

CD4: CD4+ T-cell;

IQR: interquartile range;

SD: standard deviation;

ART: antiretroviral therapy,

TMP/SMX: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Tests of association between characteristics and temperature classification were performed using Chi squared, Fisher’s exact, and Student’s t-tests, where appropriate.

A total of 456 HIV-infected women were normothermic. However, only 196/456 (43%) were randomly selected for in-depth data collection on ART and TMP/SMX use.

Evaluation of fever and hypothermia

At least one temperature measurement was recorded for 4,176/4,231 (99%) of participants. Fever and hypothermia incidence did not differ by HIV status (P=0.95). Of 205 (5%) febrile or hypothermic participants, 174 (85%) completed physical exam and symptom questionnaire, blood and urine cultures, and malaria RDT. Seven of 205 (3%) withdrew from the study, and seven (3%) refused sample collection and clinical evaluation but did not withdraw. Another 17 underwent partial microbiological evaluation: 11 (5%) were missing urine culture, one (0.5%) was missing blood culture, three (1%) refused sample collection but underwent clinical examination, and two (1%) refused clinical examination and sample collection but completed the symptom questionnaire (Fig. 1).

In-hospital postpartum infection incidence

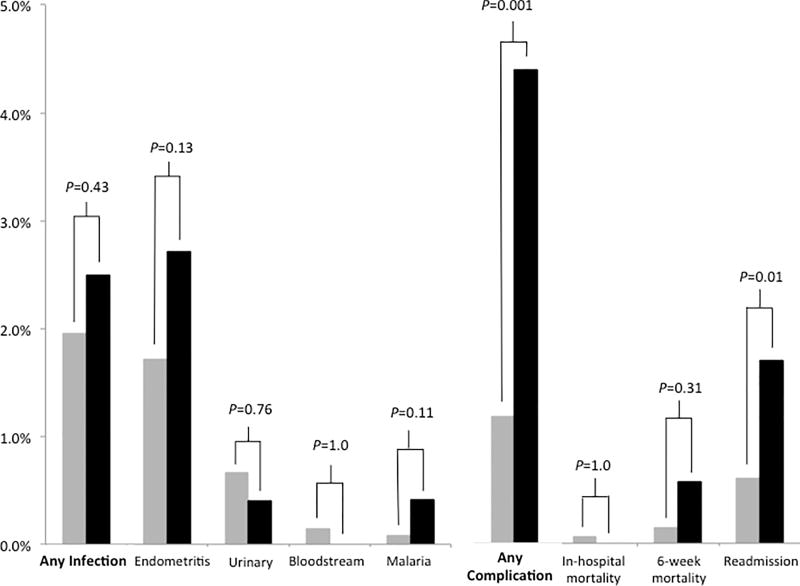

Overall, 84/174 (48%) febrile or hypothermic participants who underwent full clinical and microbiological evaluation met criteria for one or more postpartum infections. Incidence of postpartum infection (composite primary outcome) did not differ by HIV status (2.0 vs. 2.5%, P=0.43, Fig. 2). Postpartum endometritis was the most common source, identified in 76/193 (39%) who underwent clinical evaluation. The overall incidence of endometritis was 1.8%, and did not differ by HIV status (1.7 vs. 2.7%, P=0.13). Of 76 women with clinical endometritis, 61 (82%) underwent cesarean delivery. Twenty-six of 175 (15%) participants with urinalysis and urine culture results met criteria for UTI. Bloodstream infection was diagnosed in 5/185 (3%) participants with blood cultures. Another 5/186 (3%) were malaria RDT-positive. The remaining 90/174 (52%) participants did not have a documented source of fever after our evaluation. Using multivariable logistic regression analysis, HIV infection was not independently associated with the composite outcome in-hospital postpartum infection (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.4, 95% CI 0.6–3.3, P=0.49, see Table 4).

Figure 2.

Postpartum infections and complications, by HIV status. "Any infection" is the primary composite outcome, "Any complication" is a secondary outcome. HIV-infected women are represented by black bars, HIV-uninfected women are represented by grey bars.

Table 4.

Outcomes of participants with and without HIV infection.

| Characteristic | Number (%) HIV-uninfected n=1570 |

Number (%) HIV-infected n=215 |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATERNAL CHART DIAGNOSIS | |||

| Premature rupture of membranes | 24 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | 1.0 |

| Pre-eclampsia or eclampsia | 17 (1.1) | 2 (0.9) | 1.0 |

| Puerperal sepsis | 12 (0.8) | 4 (1.9) | 0.12 |

| Obstructed or prolonged labor | 124 (8.0) | 14 (6.6) | 0.49 |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 7 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 0.29 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| SINGLETON FETAL AND BIRTH OUTCOMES | |||

| Neonate outcome at time of maternal discharge | 0.94 | ||

| Stillborn | 50 (3.4) | 6 (3.0) | |

| Live birth | 1410 (96.0) | 192 (96.5) | |

| Live birth, in hospital death | 9 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Birth weight (kilograms) | 0.24 | ||

| <2.5 | 85 (5.8) | 12 (6.0) | |

| 2.5–3.5 | 1056 (71.4) | 138 (68.7) | |

| 3.6–4.0 | 269 (18.2) | 46 (22.9) | |

| >4 | 69 (4.7) | 5 (2.5) | |

| 1-minute Apgar score (mean (SDa)) | 8.3 (2) | 8.3 (2) | 0.72 |

| 5-minute Apgar score (mean (SD)) | 9.5 (2) | 9.5 (2) | 0.94 |

| 5-minute Apgar score (<7) | 20 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.50 |

| MATERNAL READMISSION AND COMPLICATIONS | |||

| Readmission to MRRHb during postpartum period | 23 (0.6) | 8 (1.7) | 0.01 |

| One or more complication | 18 (1.2) | 9 (4.4) | 0.001 |

| Ruptured uterus | 4 (0.3) | 2 (1.0) | 0.16 |

| Blood transfusion | 3 (0.2) | 3 (1.5) | 0.03 |

| Re-operation | 2 (0.1) | 2 (1.0) | 0.07 |

| Cesarean surgical site wound infection | 8 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0.34 |

| Maternal death in-hospital | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

SD: standard deviation;

MRRH: Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital.

Tests of association between complications/outcomes and HIV infection were performed using Chi squared, Fisher’s exact, and Student’s t-tests, where appropriate.

Secondary maternal and neonatal outcomes

Chart diagnosis of obstructed labor, premature rupture of membranes and chorioamnionitis did not differ by HIV infection status (see Table 4), and neonatal outcomes were similar. HIV-infected women were significantly more likely to than HIV-uninfected women to be readmitted to MRRH within the 6-week postpartum period (1.7 vs. 0.6%, P=0.01, see Table 4 and Fig. 2), and to suffer one or more in-hospital complications (4.4 vs. 1.2%, P=0.001) including blood transfusion (1.5 vs. 0.2%, P=0.03).

Discussion

We found in-hospital postpartum infection incidence was low (2.0%), and HIV infection was not associated with increased risk of postpartum infection (aOR 1.4, 95% CI 0.6–3.3, P=0.49) in a cohort of Ugandan women hospitalized for delivery or postpartum care. Notably, 96% of HIV-infected women in this study were on ART at the time of delivery and the median CD4 count (487cells/mm3) reflected relatively intact immune function. Our findings contrast with studies from the era before ART was in common use, which described increased risk of maternal mortality and postpartum infection in HIV-infected women.(Black et al., 2009; Calvert & Ronsmans, 2013; Fawcus et al., 2005; Garenne et al., 2008; Khan et al., 2001; Louis et al., 2007; Maiques-Montesinos et al., 1999; McIntyre, 2003; Moodley & Moodley, 2005; Nduati et al., 2001; Ronsmans & Graham, 2006; Semprini et al., 1995; van den Akker et al., 2011; Zvandasara et al., 2006) Indeed, a 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis investigating HIV and risk of direct obstetric complications, in which 42% of included studies were conducted in areas where ART was available, reported HIV-infected women had three times the odds of postpartum infection than HIV-uninfected women.(Calvert & Ronsmans, 2013) Studies included from sub-Saharan Africa found modest increases in obstetric and non-obstetric infections among HIV-infected women,(Ikpim, Edet, Bassey, Asuquo, & Inyang, 2016; Semprini et al., 1995; van den Akker et al., 2011; Zvandasara, Saungweme, Mlambo, & Moyo, 2007) though one study reported low ART coverage of HIV-infected women (24%) with 45% of documented CD4 counts <250 cells/mm3;(van den Akker et al., 2011). Multivariable regression findings in another study revealed that only HIV-infected women with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3 were at increased risk of infectious complications(Semprini et al., 1995). Similar to our results, a South African study found no association between HIV status and incident postpartum infection in crude or multivariable models (relative risk 1.14, 95% CI 0.85–1.53, P=0.39), which the authors attribute to CD4 counts >350 cells/mm3 in most participants.(Sebitloane, Moodley, & Esterhuizen, 2011)

Our findings of no increased risk of fever, infection, in-hospital or 6-week mortality among HIV-infected women may reflect improved outcomes associated with widespread ART and TMP/SMX use in our study population. Although we did not measure HIV viral load in our cohort, prior research in Mbarara, Uganda demonstrated high ART adherence and suppressed HIV viral loads during pregnancy and the postpartum period.(Matthews et al., 2016) In our cohort, median CD4 count was >500 cells/mm3, suggesting a relatively healthy population of HIV-infected women. Moreover, febrile/hypothermic HIV-infected women were less likely to report current TMP/SMX prophylaxis or ART, suggesting additional benefit for its use even among individuals with high CD4 counts in the region.(Bwakura-Dangarembizi et al., 2014; Campbell et al., 2012) Our findings are generalizable to other settings in sub-Saharan Africa with high ART coverage and routine use of TMP/SMX prophylaxis.

While we found no association between HIV infection and risk of postpartum infection, fever, or hypothermia; significantly more HIV-infected than HIV-uninfected women (4.4% vs. 1.2%, P=0.001) developed an in-hospital postpartum complication, including uterine rupture, re-operation, and/or blood transfusion. HIV infection has been associated with increased risk of postpartum transfusion in other studies, including an 8-year Canadian nationwide inpatient database analysis reporting increased odds of blood transfusion (OR 3.11, 95% CI 2.53–3.83) in HIV-infected women.(Arab, Czuzoj-Shulman, Spence, & Abenhaim, 2016) A South African study reported similar findings, postulating that increased transfusion risk resulted from unaddressed antenatal anemia, more common in HIV-infected patients.(Bloch et al., 2015) Despite these reports, a 2013 systematic review concluded that evidence of difference in risk of non-infectious obstetric complications between HIV-infected and -uninfected women was weak and inconsistent.(Calvert & Ronsmans, 2013)

Lastly, we found HIV infection was associated with increased risk of readmission to the same hospital within the postpartum period. A Canadian cohort study also reported higher 30-day risk of readmission risk in HIV-infected than -uninfected women (2.8 vs. 1.1%), though the difference was attenuated after multivariable adjustment for sociodemographic factors.(Macdonald et al., 2015) The association we found between HIV infection and readmission risk could be due to greater post-discharge morbidity in this population, unaccounted-for sociodemographic factors, more care-seeking behavior among HIV-infected women, or a greater likelihood of returning to the same hospital due to proximity, since a greater proportion of HIV-infected women resided in the same district as the hospital.

There are several strengths to our study, including its prospective design, large size, near-complete enrollment of eligible women, and in-depth evaluation of febrile and hypothermic participants. Understanding infection risk among HIV-infected and -uninfected women delivering at sub-Saharan African hospitals is of increasing importance as women are encouraged to deliver their babies at health facilities. The United Nations reported that >71% of births in 2014 were attended by skilled healthcare personnel,(U.N., 2014) and the Ugandan Ministry of Health reported that between 2011–2016, 70% of rural-dwelling women and 88% of urban-dwellers delivered their last live birth at a health facility.(Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report, 2017)

In our study, overall in-hospital infection incidence (2.0%) was lower than predicted, limiting our ability to determine outcome differences between HIV-infected and –uninfected women. Low postpartum infection incidence may be due in part to the routine practice of administering antibiotics to women delivering by cesarean. Multiple studies have examined the impact of antibiotic prophylaxis during pregnancy,(Aboud et al., 2009) delivery,(Sebitloane, Moodley, & Esterhuizen, 2008) or postpartum(Pinto-Lopes, Sousa-Pinto, & Azevedo, 2017) on postpartum infection incidence, with mixed results.(Aboud et al., 2009; Sebitloane et al., 2008) The proportion of women delivering by cesarean was high, accounting for 50% of all deliveries in this study. This figure may be an overestimate of the true cesarean delivery rate due to early discharge and non-enrollment of some women delivering vaginally. In addition, the study was carried out at a regional referral hospital, and referral of women with complicated labor may partly explain the high proportion of cesarean deliveries compared to the national proportion, estimated at 5%(Cavallaro et al., 2013). Cesarean delivery mode is the single greatest risk factor for postpartum infection,(Smaill & Grivell, 2014) and 82% of the women developing postpartum endometritis in our study delivered by cesarean. The high proportion of cesarean deliveries and postpartum antibiotic use in our study should be taken into account when considering our results, and our results, which may not be generalizable to settings with low antibiotic use or low prevalence of cesarean deliveries. Other limitations of our study include lack of clinical evaluation for other causes of postpartum fever, including cesarean section surgical site infections. Though wound infection diagnoses were abstracted from charts, documentation was incomplete and we were unable to confirm them clinically. Due to resource constraints, we were also unable to perform clinical or microbiological testing of normothermic participants. However, most clinically significant in-hospital postpartum infections should manifest with fever or hypothermia, leaving few infections undiagnosed in normothermic women.

In conclusion, for women in rural Uganda with high rates of ART coverage, HIV infection did not predict postpartum infection or mortality, but was associated with increased risk of postpartum complications.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with composite postpartum infection outcome.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Characteristic | ORa (95% CIc) |

P-value* | aORb (95% CI) |

P-value* |

| Cesarean delivery | 7.7 (3.9–15.1) | <0.001 | 3.9 (1.5–10.3) | 0.006 |

| Number of days in hospital | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.001 |

| Attended antenatal clinic ≥4 times | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.20 | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 0.02 |

| Multiparity | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | <0.001 | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) | 0.06 |

| Age | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.9–1.01) | 0.08 |

| Formal employment | 0.6 (0.4–0.97) | 0.04 | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.20 |

| Number of vaginal exams in labor | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.97 | 0.90 (0.8–1.1) | 0.24 |

| Obstructed labor diagnosis | 2.5 (1.3–4.6) | 0.005 | 1.4 (0.6–3.2) | 0.40 |

| Referred to MRRHd | 2.3 (1.4–4.0) | 0.002 | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 0.75 |

| Admitted without a bed (on floor) | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | 0.45 |

| Number of urinary catheter days | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.53 |

| Number of hours in labor | 1.0 (1.0–1.01) | 0.26 | 1.0 (0.98–1.01) | 0.66 |

| Residence in Mbarara | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 0.08 | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | 0.52 |

| HIV infection | 1.0 (0.5–2.1) | 0.91 | 1.4 (0.6–3.3) | 0.49 |

OR: odds ratio;

aOR: adjusted odds ratio;

CI: confidence interval;

MRRH: Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital;

Tests of association between cohort characteristics and the presence or absence of postpartum infection were performed using univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the cohort participants and to the Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital Maternity Staff, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, MRRH ISS Clinic, and Epicentre Mbarara for their partnership in this research. The authors also thank Becton Dickinson (BD) for their generous donation of blood culture bottles for use in this study.

Sources of Research Funds

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Research Training Grant #R25 TW009337 funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Mental Health (to LMB); National Institutes of Health T32 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award #5T32AI007433-22 (to LMB); the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Global Health (to LMB); Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI060354), which is supported by National Institutes of Health Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers (to IVB); National Institutes of Health K23 MH09916 (to MJS); the Sullivan Family Foundation (to DRB); logistical support from Harvard Catalyst; and Becton, Dickinson and Company (BD) donated blood culture bottles for use in this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors disclose that no financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct applications of our research.

Geolocation information

This research was performed in Mbarara, Uganda at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, which shares a campus with the Mbarara University of Science and Technology. The geographical coordinates are 0°36'59.0''S, 30°39'32.0''E.

References

- Aboud S, Msamanga G, Read JS, Wang L, Mfalila C, Sharma U, Fawzi WW. Effect of prenatal and perinatal antibiotics on maternal health in Malawi, Tanzania, and Zambia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(3):202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arab K, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Spence A, Abenhaim HA. Obstetrical Outcomes of Patients With HIV in Pregnancy, a Population Based Cohort [25] Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(Suppl 1):10s. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000483641.28007.ca. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bako B, Audu BM, Lawan ZM, Umar JB. Risk factors and microbial isolates of puerperal sepsis at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri, North-eastern Nigeria. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(4):913–917. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebell LM, Ngonzi J, Bazira J, Fajardo Y, Boatin AA, Siedner MJ, Boum Y., 2nd Antimicrobial-resistant infections among postpartum women at a Ugandan referral hospital. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black V, Brooke S, Chersich MF. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus treatment on maternal mortality at a tertiary center in South Africa: a 5-year audit. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(2 Pt 1):292–299. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181af33e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch EM, Crookes RL, Hull J, Fawcus S, Gangaram R, Anthony J, Murphy EL. The impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on obstetric hemorrhage and blood transfusion in South Africa. Transfusion. 2015;55(7):1675–1684. doi: 10.1111/trf.13040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bwakura-Dangarembizi M, Kendall L, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Nahirya-Ntege P, Keishanyu R, Nathoo K, Prendergast AJ. A randomized trial of prolonged co-trimoxazole in HIV-infected children in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(1):41–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert C, Ronsmans C. HIV and the risk of direct obstetric complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e74848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Moore D, Degerman R, Kaharuza F, Were W, Muramuzi E, Tappero JW. HIV-infected ugandan adults taking antiretroviral therapy with CD4 counts >200 cells/muL who discontinue cotrimoxazole prophylaxis have increased risk of malaria and diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):1204–1211. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro FL, Cresswell JA, Franca GV, Victora CG, Barros AJ, Ronsmans C. Trends in caesarean delivery by country and wealth quintile: cross-sectional surveys in southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(12):914–922d. doi: 10.2471/blt.13.117598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolidated Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of HIV in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda Ministry of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dolea C, Stein C. Global burden of maternal sepsis in the year 2000. 2003 (Producer). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bod_maternalsepsis.pdf.

- Fawcus SR, van Coeverden de Groot HA, Isaacs S. A 50-year audit of maternal mortality in the Peninsula Maternal and Neonatal Service, Cape Town (1953–2002) BJOG. 2005;112(9):1257–1263. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garenne M, McCaa R, Nacro K. Maternal mortality in South Africa in 2001: From demographic census to epidemiological investigation. Popul Health Metr. 2008;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng EH, Bwana MB, Kabakyenga J, Muyindike W, Emenyonu NI, Musinguzi N, Bangsberg DR. Diminishing availability of publicly funded slots for antiretroviral initiation among HIV-infected ART-eligible patients in Uganda. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilstrap LC, 3rd, Cunningham FG. The bacterial pathogenesis of infection following cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(5):545–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):117–171. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The HIV and AIDS Uganda Country Progress Report 2014. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda AIDS Commission; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, Nicolle LE. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(5):625–663. doi: 10.1086/650482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikpim EM, Edet UA, Bassey AU, Asuquo OA, Inyang EE. HIV infection in pregnancy: maternal and perinatal outcomes in a tertiary care hospital in Calabar, Nigeria. Trop Doct. 2016;46(2):78–86. doi: 10.1177/0049475515605003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janni W, Schiessl B, Peschers U, Huber S, Strobl B, Hantschmann P, Kainer F. The prognostic impact of a prolonged second stage of labor on maternal and fetal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(3):214–221. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesson A, Sorrell T. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in pregnancy. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;7(1):45–74. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(05)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M, Pillay T, Moodley JM, Connolly CA. Maternal mortality associated with tuberculosis-HIV-1 co-infection in Durban, South Africa. Aids. 2001;15(14):1857–1863. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109280-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourtis AP, Ellington S, Pazol K, Flowers L, Haddad L, Jamieson DJ. Complications of cesarean deliveries among HIV-infected women in the United States. Aids. 2014;28(17):2609–2618. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinsky SE. Obstetric infections. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29(3):509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis J, Landon MB, Gersnoviez RJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Rouse DJ, Mercer BM. Perioperative morbidity and mortality among human immunodeficiency virus infected women undergoing cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):385–390. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275263.81272.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald EM, Ng R, Yudin MH, Bayoumi AM, Loutfy M, Raboud J, Antoniou T. Postpartum Maternal and Neonatal Hospitalizations Among Women with HIV: A Population-Based Study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2015;31(10):967–972. doi: 10.1089/aid.2015.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj D. Puerperal pyrexia: a review. Part I. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007a;62(6):393–399. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000265998.40912.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj D. Puerperal Pyrexia: a review. Part II. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007b;62(6):400–406. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000266063.84571.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiques-Montesinos V, Cervera-Sanchez J, Bellver-Pradas J, Abad-Carrascosa A, Serra-Serra V. Post-cesarean section morbidity in HIV-positive women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(9):789–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews LT, Kaida A, Kanters S, Byakwagamd H, Mocello AR, Muzoora C, Hunt PW. HIV-infected women on antiretroviral treatment have increased mortality during pregnant and postpartum periods. Aids. 2013;27(Suppl 1):S105–112. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews LT, Ribaudo HB, Kaida A, Bennett K, Musinguzi N, Siedner MJ, Bangsberg DR. HIV-Infected Ugandan Women on Antiretroviral Therapy Maintain HIV-1 RNA Suppression Across Periconception, Pregnancy, and Postpartum Periods. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(4):399–406. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000000874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre J. Mothers infected with HIV. Br Med Bull. 2003;67:127–135. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Muyindike W, Matthews LT, Kanyesigye M, Siedner MJ. Program Implementation of Option B+ at a President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief-Supported HIV Clinic Improves Clinical Indicators But Not Retention in Care in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31(8):335–341. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moodley J, Moodley D. Management of human immunodeficiency virus infection in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19(2):169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nduati R, Richardson BA, John G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Mwatha A, Ndinya-Achola J, Kreiss J. Effect of breastfeeding on mortality among HIV-1 infected women: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9269):1651–1655. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04820-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngonzi J, Tornes YF, Mukasa PK, Salongo W, Kabakyenga J, Sezalio M, Van Geertruyden JP. Puerperal sepsis, the leading cause of maternal deaths at a Tertiary University Teaching Hospital in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0986-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Lopes R, Sousa-Pinto B, Azevedo LF. Single dose versus multiple dose of antibiotic prophylaxis in caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bjog. 2017;124(4):595–605. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JS, Tuomala R, Kpamegan E, Zorrilla C, Landesman S, Brown G, Thompson B. Mode of delivery and postpartum morbidity among HIV-infected women: the women and infants transmission study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26(3):236–245. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200103010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reniers G, Slaymaker E, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Nyamukapa C, Crampin AC, Herbst K, Zaba B. Mortality trends in the era of antiretroviral therapy: evidence from the Network for Analysing Longitudinal Population based HIV/AIDS data on Africa (ALPHA) Aids. 2014;28(Suppl 4):S533–542. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshi P, Lone IM. Human immunodeficiency virus and pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281(5):781–792. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale AC, Mwaniki M, Newton CR, Berkley JA. Maternal and early onset neonatal bacterial sepsis: burden and strategies for prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(7):428–438. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70172-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebitloane HM, Moodley J, Esterhuizen TM. Prophylactic antibiotics for the prevention of peripartum infectious morbidity in women infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;198(2):189, e181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebitloane HM, Moodley J, Esterhuizen TM. Pathogenic lower genital tract organisms in HIV-infected and uninfected women, and their association with postpartum infectious morbidity. S Afr Med J. 2011;101(7):466–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semprini AE, Castagna C, Ravizza M, Fiore S, Savasi V, Muggiasca ML, et al. The incidence of complications after caesarean section in 156 HIV-positive women. Aids. 1995;9(8):913–917. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaill FM, Grivell RM. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):Cd007482. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007482.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staveteig S, Croft TN, Kampa KT, Head SK. Reaching the 'first 90': Gaps in coverage of HIV testing among people living with HIV in 16 African countries. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.N. The Millennium Development Goals Report. New York: United Nations; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda AIDS Indicator Survey 2011. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: UBOS and ICF: Uganda Bureau of Statistcs (UBOS) and ICF; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Uganda HIV and AIDS Country Progress Report June 2015–June 2016. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda AIDS Commission; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update 2016. 2016a Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/Global-AIDS-update-2016.

- UNAIDS. Prevention Gap Report. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2016b. [Google Scholar]

- van den Akker T, de Vroome S, Mwagomba B, Ford N, van Roosmalen J. Peripartum infections and associated maternal mortality in rural Malawi. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):266–272. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182254d03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dillen J, Zwart J, Schutte J, van Roosmalen J. Maternal sepsis: epidemiology, etiology and outcome. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2010;(23):249–254. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328339257c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandabwa JN, Doyle P, Longo-Mbenza B, Kiondo P, Khainza B, Othieno E, Maconichie N. Human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS and other important predictors of maternal mortality in Mulago Hospital Complex Kampala Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:565. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Beyond the Numbers: Reviewing Maternal Deaths and Complications to Make Pregnancy Safer. Geneva: 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 15 facts on HIV treatment scale-up and new WHO ARV guidelines 2013. 2017 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/15facts/en/

- Wilson ML, Gaido L. Laboratory diagnosis of urinary tract infections in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(8):1150–1158. doi: 10.1086/383029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoe DS, Christiansen CL, Johnson R, Sands KE, Livingston J, Shtatland ES, Platt R. Epidemiology of and surveillance for postpartum infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(5):837–841. doi: 10.3201/eid0705.010511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvandasara P, Hargrove JW, Ntozini R, Chidawanyika H, Mutasa K, Iliff PJ, Humphrey JH. Mortality and morbidity among postpartum HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in Zimbabwe: risk factors, causes, and impact of single-dose postpartum vitamin A supplementation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(1):107–116. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000229015.77569.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvandasara P, Saungweme G, Mlambo JT, Moyo J. Post Caesarean section infective morbidity in HIV-positive women at a tertiary training hospital in Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 2007;53(9–12):43–47. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v53i9-12.62615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]