Abstract

Investigating the interplay between cytochrome-P450 and its redox partners (CPR and cytochrome-b5) is vital for understanding the metabolism of most hydrophobic drugs. Dynamic structural interactions with the ternary complex, with and without substrates, captured by NMR reveal a gating mechanism for redox partners to promote P450 function.

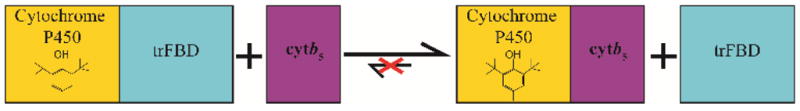

Graphical Abstract

Cytochrome P450s (P450s) are a ubiquitous superfamily of enzymes responsbile for metabolizing a dazzling array of exogenous and endogenous compounds, including carcinogens, hormones, and over 75% of the drugs on the current market.[1–5] For each turn of the catalytic cycle, P450 requries two electrons which are delivered by P450’s two redox partners, cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) and cytochrome b5 (cytb5).[6] CPR and cytb5 have different capabilites of interacting with P450 and their unbalanced stoichiometry within the endoplasmic reticulum, make it an interesting and challenging question to understand the interplay between this ternary complex.

CPR is a 78 kDa protein comprised of four major domains: a NADPH/FAD binding domain, a linker domain, a FMN binding domain (FBD), and a N-terminal transmembrane domain.[5,7] After NADPH binding, electrons are shuttled through the FAD cofactor to the FMN cofactor to the heme group of the electron acceptor P450, a process involving both intra- and inter-protein electron transfers. The inter-protein electron transfer step depends on association and interaction between FBD and P450. Studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using the FBD alone to study the interaction between CPR and P450.[8,9]

The third protein of this ternary complex is cytb5, a 15.7 kDa protein, which is only capable of donating the second electron to P450 due to the large difference in redox potential between cytb5 and ferric P450.[5,10,11] Although P450 metabolism can function with only CPR as the sole electron donor, deletion of cytb5 causes extreme effects of P450 catalysis both sizeable increases and decreases in metabolism rates.[12, 13] Through kinetic experiments, cytb5 has been shown to affect the catalytic activity of over twenty P450 isoforms, including 3A4, 2B6, 2C9, and 2E1.[2,14,15] Cytb5 seems to have some level of substrate or reaction preference, best seen through its influence of the 17,20-lyase reaction in P450 17α1.[16,17] Various recent studies with microsomal P450 have helped to elucidate that cytb5 can stimulate a reaction through increasing the rate of formation of the catalytically active oxidizing species and product formation.[6,18] Overall, the role of cytb5 in P450 metabolism is very perplexing, since it has been reported to stimulate, inhibit, or not affect P450 activities depending on the substrates involved, the particular isoform of P450, and the experimental conditions. In this study, we investigate the effect of substrates on the complex formation between cytb5 and P450, FBD and P450, and the ternary complex, demonstrating the differential regulation potential of substrates. Using NMR, we probe the relationship between rabbit full-length P450 2B4, FBD, and full-length cytb5 at residue specific resolution.

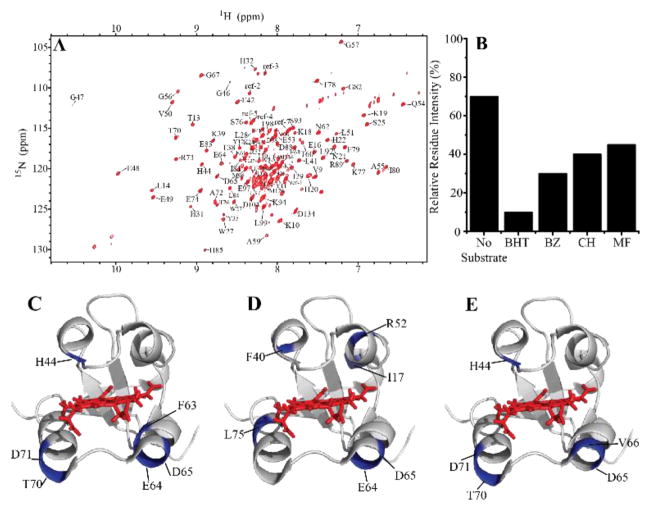

Cytb5’s effect on P450 metabolism is both isoform and substrate-dependent. Differences in rates of metabolism of various drugs with the addition or absence of cytb5 have been noted for a variety of isoforms and substrates[14,19–22], but differences in complex formation strength has not been investigated which this study provides for the first time. We use NMR to monitor changes in complex formation between P450 2B4 and cytb5. As previously described,[23] the substrate butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) enhances the complex formation between cytb5 and P450, as measured by the increasing 15N-NMR line width. A similar strategy was applied in this study to test a variety of substrates: benzphetamine (BZ), methoxyflurane (MF), and cyclohexane (CH). 15N-labeled rabbit cytb5 was expressed, purified, and used to form a 1:1 complex with P450. 2D-TROSY-HSQC NMR experiments were used to monitor changes in complex formation as each substrate was titrated into the protein-protein complex and the line-broadening of cytb5 residues was monitored. One measure of the complex stability (or the strength of complex formation) is through understanding the line-broadening of residues which can be measured by the overall average signal intensity change. Cytb5 alone would have 100% signal intensity, whereas cytb5 in complex with P450 has a signal intensity of ~70%[24]. In general, all substrates used (BHT, BZ, MF, and CH) led to an increase in line-widths of cytb5 resonances (Figure 1A). Substrates modulate this interaction to varying degrees with BHT strengthening the complex formation followed by BZ, and lastly CH and MF. Residues with relative intensity loss more than one standard deviation below average were considered to be significantly broadened upon binding to P450 and highly implicated to be part of the binding interface. These residues are mapped onto cytb5: H44, F63, E64, D65, T70, and D71 in the presence of BZ (Figure 1C); H44, D65, V66, T70, and D71 in the presence of cyclohexane (Figure 1D); and I17, F40, R52, E64, D65, L75 for methoxyflurane (Figure 1E). All the substrate-titrated samples demonstrated overlapping regions affected by the binding to P450, mainly, the front face of cytb5 specifically on the lower cleft which is supported by the literature.[23–27]

Figure 1. Substrate effect on cytb5-P450 interaction.

(A) 2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC NMR spectrum of 15N-labeled cytb5. (B) Comparison of the average intensity of cytb5 in complex with P450 in the absence and presence of different substrates. Highlighted (in blue) residues are part of the P450-cytb5 binding interface are mapped on cytb5 (PDB: 2M33) with the heme group displayed in red sticks for (C) benzphetamine (BZ), (C) methoxyflurane (MF), and (D) cyclohexane (CH).

Next, to investigate the effect of substrates on the interaction between FBD and P450, substrates (BHT, BZ, MF) were added to 1:1 complex of 15N-uniformly labelled FBD and P450. 2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC NMR spectra were compared before and after the addition of a substrate. For all three substrates, chemical shift perturbations were negligible indicating the proteins are under fast exchange in the NMR time scale. All of the substrate additions led to very slight enhancement in line-broadening – seen as a decrease in signal intensity (Supplemental Figure 1). In general, substrates do not affect FBD-P450 2B4 interaction much implying that, within the scope of this study, complex formation between these two redox partners are not modulated by substrates.

Not much is known about the interplay between the three proteins. Structurally, we know the FBD of CPR and cytb5 share an overlapping binding surface on P450.[2,6,8,16,17] As CPR/FBD has a higher affinity for P450 than does cytb5[28], CPR/FBD has the potential to bind preferentially to P450 in the presence of cytb5. The rate constants for the interprotein electron transfer reactions are of the same magntiude for CPR-P450 and cytb5-P450 which elimintes the ability to transfer an electron to P450 from being the driving force behind the choice of redox partner. One hypothesis is that concentration is the major factor behind P450’s choice of redox partner where the poorer binding redox partner (cytb5 in this case) would have to be present at a higher concentation in order to be successful in outcompeting the stronger binding redox partner (CPR).[28] As these two proteins have unique, but overlapping binding sites on P450[2,6,22], this means they are in direct competition and these two enzymes cannot bind to P450 at the same time.

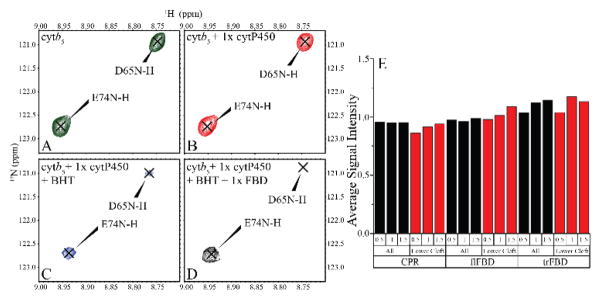

Due to the higher affinity favoring the complex formation of CPR/FBD and P450, we tested the ability of CPR/FBD to dislodge cytb5 from its complex with P450. We first formed a 1:1 complex between 15N-labeled cytb5 and P450, then titrated in CPR or FBD while 2D-TROSY-HSQC NMR spectra were utilized to monitor signal intensity (Figure 2, SI Figures 2–8). As CPR is titrated into the 1:1 cytb5:P450 complex, we should see an increase in overall signal intensity of cytb5 if CPR is able to disrupt the complex. Surprisingly, this effect was not seen. The cytb5:P450 complex was stable and unaffected even in the excess of CPR, meaning that CPR is unable to interrupt or hinder the cytb5-P450 interaction over the concentrations of 0.5 to 1.5 molar equivalents (Figure 2E, black). This trend holds true for looking at the overall signal intensity as well as the intensity of cytb5 residues (i.e, 60–70) implicated in binding with P450 (Figure 2E, red). This experiment was performed with CPR, FBD, and full-length FBD (flFBD); flFBD is FBD with the transmembrane domain which was used to rule out the influence of the transmembrane domain in this interaction. Very similar results were obtained for flFBD and FBD demonstrating that no form of CPR is capable of disrupting the cytb5-P450 complex, and also proving the feasibility of working with FBD to simplify this question. This experiment was repeated with a substrate, BHT, and similar results were seen with FBD unable to disrupt the cytb5-P450 complex. Figure 2A–D demonstrates residue-specific change in signal intensity when binding to P450 or P450+BHT, and upon titration with FBD. No significant change was observed for residues D65 and E74; while D65 has been identified in the binding interface with P450[23–27], E74 has not.

Figure 2. Cytb5-P450 complex is unperturbed by interaction with CPR and its variants.

2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC NMR spectral regions of 15N-labeled cytb5 reveal changes due to interactions with P450, BHT, and CPR variants. (A) Free 15N-cytb5 (green), (B) 15N-cytb5 titrated with 1 molar equivalent of P450 (red), (C) 15N-cytb5+P450 titrated with BHT (blue), and (D) 15N-cytb5+P450+BHT after FBD titration (black). (E) The average signal intensity of cytb5 residues (total residues in black; residues in the lower cleft (60–70) in red) over the course of a titration with CPR, flFBD, or trFBD at the indicated molar ratios (0.5, 1, and 1.5). Negligible change in the observed signal intensity indicates cytb5 is not replaced from the cytb5-P450 complex by CPR or its variants.

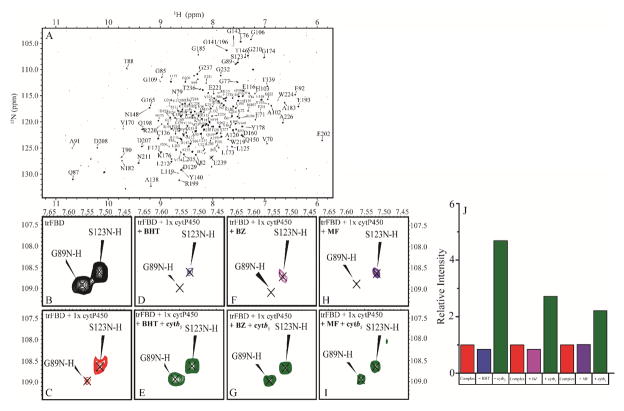

As FBD was shown to be unable to disrupt the cytb5-P450 complex, we carried out the “opposite” experiment by testing the ability of cytb5 to destabilize the FBD-P450 complex. Uniformly 15N-labeled FBD was expressed, purified, and used to form a 1:1 complex with P450. When cytb5 was titrated into this complex, the average signal intensity of FBD residues observed from TROSY-HSQC spectra greatly increased. Our results clearly show (Figure 3) that cytb5 is capable of dislodging P450-bound FBD into free solution. It is important to clarify that the ratio of cytb5 added was not in excess meaning that this phenomenon is not (solely at least) a concentration based effect.

Figure 3. Cytb5 disrupts complex between FBD and P450 in a substrate dependent manner.

2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC NMR spectra of 15N-labeled FBD reveal changes due to interaction with P450, substrates, and cytb5. (A) 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC NMR spectrum of 15N-FBD. Example residues are zoomed in (B) 15N-FBD in solution (black), (C) 15N-FBD titrated with 1 molar equivalent of P450 (red), 15N-FBD+P450 titrated with a substrate BHT (blue, D), BZ (magenta, F), or MF (purple, H), and 15N-FBD+P450+substrate titrated with cytb5 (green) for BHT (E), BZ (G), and MF (I). (J) Average signal intensity of 15N-FBD quantified after the addition of P450, P450+substrate (BHT, BZ, or MF), and P450+substrate (BHT, BZ, or MF) +cytb5.

As we have shown, substrates can greatly enhance the interaction between cytb5 and P450 while only minimally affecting the complex between FBD and P450. Cytb5 has been shown to exert substrate-dependent effects on P450 catalysis. We performed the same experiment but we added various substrates (BHT, BZ, and MF) to the 1:1 FBD:P450 complex to ascertain if ligands affect cytb5’s ability to dislodge FBD from P450 (SI Figures 9–16). Then cytb5 was added and the resulting change in FBD average signal intensity was quantified. Our results (Figure 3) demonstrate a substrate dependent modulation of cytb5’s ability to disrupt complex formation. Figure 3B–I displays residue G89, which has been implicated in FBD binding to P450[28], as well as S123 which is not involved. The significant loss of G89’s peak intensity after titration with P450 or P450+substrate and restoration after cytb5 additon confirms our conclusion that cytb5 is capable of dislodging FBD from the P450-FBD complex. The strongest effect was observed with BHT, followed by BZ and MF. With BHT and BZ, ~100% FBD was freed from the P450-bound state, while in the presence of MF, FBD still remained partially bound to P450. This difference between various substrates suggests some sort of mechanism that is regulated by different substrates. It has been reported in the literature that cytb5 stimulates P450 activity to a much higher extent for MF than BZ: 8.5-fold increase in activity versus 1.3-fold increase[6,29,30]. This has been related to an increased coupling efficiency due to electron transfer, as well as allosteric activation mediated by cytb5.[6] In our experiment, we see an inverse of this relation – that the interaction strength of the complex is much higher for BZ over MF. Based on these results, we propose a competitive binding mechanism where cytb5 and CPR are competing to bind to an overlapping, but unique binding site on P450 and substrates help to modulate this effect (Figure 4).

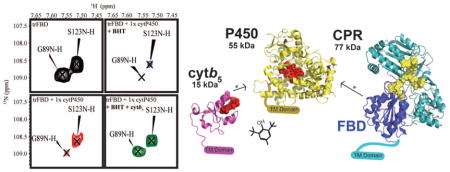

Figure 4. Schematic of the ternary interplay.

When cytb5 is added to the BHT-P450 complex and FBD, cytb5 is able to replace FBD to form a cytb5-P450 complex. On the other hand, FBD is unable to replace cytb5 from the cytb5-P450 complex.

One explanation for this inverse relationship of metabolism increase and complex formation is that the first electron transfer to P450, which can only be fulfilled by CPR, may be inhibited due to cytb5 occupying the binding interface on P450. The addition of a substrate to P450 could increase cytb5’s affinity for P450 which allows it to outcompete CPR, which gives newfound insight into past findings where cytb5 was found to inhibit BZ demethylation.[31] A previous study demonstrated that these proteins have an overlapping but unique binding site on P450, which indicates that the two enzymes cannot bind simultaneously. This can explain why cytb5’s stimulation effect on P450 activity changes for different substrates; each substrate could alter cytb5’s affinity for P450 in a different way. Other P450 isoforms have shown this substrate-dependent increase in binding affinity, most recently, with CYP101D1’s binding affinity for its redox partner, Adx, after the additon of camphor.[32] Another explanation is the concept of P450’s structural plasticity whereby after ligand binding P450 undergoes a conformational change.[33] This conformational change could favor one redox partner binding over the other. The larger of the substrates that we tested, BHT and BZ, are bulky compounds which could have more of a rigidifying effect on the distal region on P450, leading to allosteric changes in the proximal, redox partner binding site of P450 whereas a smaller compound like MF has a lesser effect. While P450s are known to be highly homologous in their proximal site, their distal region is more varied which could explain the differences amongst isoforms of P450. Thus, the results presented in this study shed light on substrate regulation on the tertiary FBD-P450-cytb5 system, providing insights into the structural basis of the interplay of the three redox partners.

In conclusion, for the first time, we have shown that substrates play very important roles in the dynamic interplay between P450 2B4 and its redox partners. Cytb5 interaction with P450 is greatly increased by the addition of substrates to varying degrees whereas FBD-P450 interaction is not significanlty affected. Although FBD and CPR have higher affiniity for P450, they are unable to dislodge cytb5 from binding to P450. Cytb5, on the other hand, is capable of disrupting the FBD-P450 complex interaction in a substrate dependent manner. Since all three proteins are membrane-anchored and membrane has been shown to play important roles on P450 function,[2,5,34] probing the roles of membrane on the ternary complex is in progress in our lab.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH (GM084018 to A.R.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Guengerich FP. Mol Interventions. 2003;3:194. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.4.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnaba C, Gentry K, Sumangala N, Ramamoorthy A. F1000Res. 2017;6:662. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11015.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guengerich FP. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:70. doi: 10.1021/tx700079z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guengerich FP, Wu ZL, Bartleson CJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:465. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dürr UH, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:3235. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Im SC, Waskell L. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;507:144. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang M, Roberts DL, Paschke R, Shea TM, Masters BS, Kim JJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang R, Zhang M, Rwere F, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:4843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.582700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estrada DF, Laurence JS, Scott EE. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:3990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.677294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Hamdane D, Im SC, Waskell L. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Zhang H, Usharani D, Bu W, Im S, Tarasev M, Rwere F, Pearl NM, Meagher J, Sun C, Stuckey J, Shaik S, Waskell L. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5080. doi: 10.1021/bi5003794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin LA, Ronseaux S, Finn RD, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:269. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.064246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finn RD, McLaughlin LA, Ronseaux S, Rosewell I, Houston JB, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803496200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamazaki H, Nakamura M, Komatsu T, Ohyama K, Hatanaka N, Asahi S, Shimada N, Guengerich FP, Shimada T, Nakajima M, Yokoi T. Protein Expression Purif. 2002;24:329. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiang JY. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1981;211:662. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schenkman JB, Jansson I. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;97:139. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estrada DF, Skinner AL, Laurence JS, Scott EE. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.560144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearl NM, Wilcoxen J, Im S, Kunz R, Darty J, Britt RD, Ragsdale SW, Waskell L. Biochemistry. 2016;55:6558. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimada T, Mernaugh RL, Guengerich FP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;435:207. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, Im SC, Waskell L. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamburini PP, White RE, Schenkman JB. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bridges A, Gruenke L, Chang YT, Vakser IA, Loew G, Waskell L. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.17036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang M, Le Clair SV, Huang R, Ahuja S, Im SC, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8392. doi: 10.1038/srep08392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang M, Huang R, Im SC, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.597096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang M, Huang R, Ackermann R, Im SC, Waskell L, Schwendeman A, Ramamoorthy A. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:4497. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentry KA, Prade E, Barnaba C, Zhang M, Mahajan M, Im SC, Anantharamaiah GM, Nagao S, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7793. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08130-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahuja S, Jahr N, Im SC, Vivekanandan S, Popovych N, Le Clair SV, Huang R, Soong R, Xu J, Yamamoto K, Nanga RP, Bridges A, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.448225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Estrada DF, Laurence JS, Scott EE. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:3990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.677294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Myshkin E, Waskell L. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:499. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canova-Davis E, Waskell L. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:2541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan ET, Coon MJ. Drug Metab Dispos. 1984;12:358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batabyal D, Poulos TL. J Inorg Biochem. 2018;183:179. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nair PC, McKinnon RA, Miners JO. Drug Metab Rev. 2016;48:434. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2016.1178771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang R, Yamamoto K, Zhang M, Popovych N, Hung I, Im SC, Gan Z, Waskell L, Ramamoorthy A. Biophys J. 2014;106:2126–2133. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.