Abstract

Objective: We clarified the relationship between the degree of subjective fatigue, sleep, and physical activity among nurses working 16-hour night shifts in a rotating two-shift system.

Materials and Methods: We investigated 15 nurses who were surveyed regarding their individual attributes, physical activity level (consumed calories), hours of sleep, sleep efficiency, sleep onset latency, sleep diary, and subjective symptoms. Nurses wore a Fitbit One (Fitbit Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) for 7 consecutive days to measure sleep and physical activity.

Results: Results were analyzed for nine participants, excluding those who withdrew or had missing data. The years of nursing experience, nurses’ age, and the length of nocturnal awakening time of the high fatigue group were significantly longer than of the low fatigue group (p < .05). Years of nursing experience in the affiliated department of the high fatigue group was significantly shorter than of low fatigue group (p < .05). The number of nightshifts during the survey period was significantly higher in the high fatigue group than in the low fatigue group. Fatigue after work and body mass index (r = 0.46, p < .001), consumed calories (r = 0.30, p < .05), bedtime (r = –0.36, p < .05), and hours of sleep (r = –0.37, p < .01) were significantly correlated; however, the sleep indices were not correlated.

Conclusion: We clarified that the degree of fatigue in nurses working 16-hour night shifts in a rotating two-shift system was related to individual factors, such as age, years of nursing experience, years of nursing experience in the affiliated department, number of nightshifts, and length of nocturnal awakening time. Nurses with greater fatigue had significant differences in their bedtime on days off and work days, which suggests that sleep rhythm may also affect fatigue.

Keywords: fatigue, nurses, physical activity, sleep, shift-work

Introduction

The increasing sophistication and complexity of medical care, aging of the patient population, and shortening of the number of days for which patients are hospitalized, all contribute to increasing nurses’ workload. According to a survey on actual working conditions, which investigated 32,372 nurses1), approximately 90% work overtime and 60% reported that their workload had increased compared to the previous year. In addition, as the working hours increased, nurses’ subjective symptoms including general fatigue and lower back pain also increase, and three out of four nurses continue to work when chronically fatigued.

A survey by the Japanese Nursing Association found that approximately 40% of nurses who left the profession due to the working environment cited that long working hours and working nightshifts were their reason for leaving2). Staff turnovers tend to be higher in hospitals with greater nightshift workloads3). The Japanese nursing system has progressed from the triple-shift system to a two-shift system. According to the survey by the Japan Nursing Association in 2010, the two-shift system is the most common (in 45.5% of hospitals), followed by the three-shift system (in 39.4% of hospitals). Respondents claimed that nightshifts of 16 hours or more accounted for 87.7% of the time spent at work4). In a two-shift work system, nurses work long hours, including the nightshift, which goes against the nurses’ biorhythm as they should be sleeping to ease fatigue. This has been reported to increase the risk of medical accidents due to fatigue and reduced attentiveness5) and the risk of disease including cancer6) and diabetes7) in nurses themselves. Consequently, countermeasures that prevent fatigue in nurses working shiftwork are necessary.

When working in a two-shift system, not changing one’s sleep pattern the day before the nightshift, and instead taking a nap during the day of the nightshift, led to reduced feelings of fatigue after the nightshift8). In addition, not being able to take a nap during nightshifts increases fatigue cumulatively9). Conversely, reports indicate that during a 16-hour nightshift, a nap is ineffective irrespective of what time the nap is taken10), and while some rest is acquired with a 2-h nap, it is insufficiently effective in eliminating sleepiness and recovering from fatigue11). This suggests that the manner of sleeping after the nightshift may hold the key to relieving fatigue.

Considering this, the relationship between nurse fatigue and sleep has been reported; however, virtual objective measurement of sleep among nurses working in a two-shift system is not available. The portable, activity meter equipped with an accelerometer (Fitbit One, US Fitbit, hereinafter abbreviated as Fitbit) is an effective tool to measure sleep. Wearing the activity meter on one’s undergarments or in a pocket enables evaluation of the quality and quantity of sleep and the sleep/wake rhythm without restricting activity. Ty et al.12) compared seven wearable devices with a medical actigraph, looking at items including number of steps, daily consumed calories, and hours of sleep. They reported the efficacy of Fitbit.

Therefore, in this study, we clarified the relationship between the fatigue level of nurses who work in a two-shift system with their sleep and amount of physical activity using the Fitbit One. We plan to use this data as a basic material in investigating measures to prevent staff turnover based on the sleep and fatigue experienced by nurses who work in a two-shift system.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Fifteen nurses working in a two-shift system in the geriatric ward at hospital A in Hokkaido, Japan, were recruited to participate. Participants were excluded if they were taking medication.

Study design

This study used a quantitative, descriptive research design, specifically a field survey from May to June 2015.

Survey items and data collection method

1) Basic attributes

First, we requested that nurses complete a survey form including the following information: age, sex, years of nursing experience, years of nursing experience at their affiliated department, number of people living in the same house who require childrearing or care, height, and body mass index (BMI). We also obtained information on the number of nightshifts they worked during the previous month and during the survey period.

2) Fatigue

To measure subjective fatigue, we used a questionnaire for work-related fatigue feelings “Jikaku-sho shirabe”13, 14), which was developed by the Industrial Fatigue Research Committee of the Japan Occupational Health in 2002. Investigation of subjective symptoms (hereinafter referred to as degree of fatigue) comprised five groups, drowsiness, instability, uneasiness, local pain or dull-ness, and eyestrain, and higher scores indicated more fatigue. We requested that the nurses state the start and end time of their working days, and the time they wake up and go to bed on their days off. From here on, the start time of their working days and waking time on days off are defined as “before” and the end time of their working days and the time they go to bed on days off are defined as “after”.

3) Physical activity and sleep

Wearable device: Nurses were requested to wear a Fitbit for 7 consecutive days to measure their sleep and amount of physical activity. A wireless activity meter, worn like a watch on the wrist, is the most common type of Fitbit; however, many medical institutions prohibit nurses wearing watches for infection prevention and for safety reasons. Therefore, we selected this miniature, light-weight device, which can be worn on the body. Fitbit uses a triaxial accelerometer and altimeter and measures motion patterns in 1-min increments. Consequently, it can measure the number of steps, distance, consumed calories, and sleep cycle of the wearer.

The participants were explained on how to use the Fitbit and were instructed to wear it consistently, except when bathing, by attaching the Fitbit to their clothing with a special clip during periods of activity and attaching the Fitbit to a wristband worn on their non-dominant arm during sleep.

Sleep diary: Nurses were instructed to write their activity status, bedtime, waking time, any sleep other than their main sleep, daytime drowsiness, and any time when the physical activity meter was removed, over a 7-day period. The described data were used in conjunction with the physical activity meter data to evaluate participants’ sleep-waking condition.

Analysis method

Descriptive statistics were conducted for the basic attributes. Consumed calories were used as physical activity indicator and the number of sleeping hours was used as sleep indicator. The following items were used to analyze sleep efficiency: time in bed, bedtime, hours of sleep, sleep onset latency, length of nocturnal awakening time, and number of nocturnal awakenings. Subjective symptom scores were collated with the time before starting work and waking time on days off as “before”, and the end of work and bedtime on days off as “after”.

The “before” and “after” scores were highly correlated (r = 0.7,p < .01); therefore, participants were divided into two groups based on the median score using the “after” scores: a group with a high and low degree of subjective fatigue (hereinafter referred to as high and low fatigue groups, respectively). The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare the basic attributes of both groups, and we conducted a comparative investigation on the relationship between the degree of subjective fatigue, basic attributes, amount of physical activity, and sleep using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. In order to investigate the difference in sleep according to the degree of fatigue on days off and working days, we compared the time asleep, number of nocturnal awakening, sleep efficiency, bedtime, etc. between the high and low fatigue groups, by days off and shifts. We used SPSS 23.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for all statistical analyses, and the level of significance was set at < 5%.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted with the approval from the ethical review board of the Graduate School of Health Sciences, Hokkaido University (14-88). The details of this study were explained to all participants before starting study; then, they each provided their written, informed consent. This study was also conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Fifteen nurses agreed to participate; however, one was excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Four participants withdrew halfway through the study and one participant had missing data; therefore, the data from nine participants were analyzed.

Overview of participants

1) Basic attributes of participants

Table 1 shows participant characteristics. The years of nursing experience ranged from 4 to 34 years. The years of nursing experience in the affiliated department ranged from 7 months to 12 years.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics.

| Total (n = 9) |

High fatigue group (n = 4) |

Low fatigue group (n = 5) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 37.9 ± 8.4 | 41.5 ± 11.4 | 35.0 ± 2.2 | 0.002 |

| Sex: Males/females, number (%) | 1 (11.1)/8 (88.9) | 0 (0)/4 (44.4) | 1 (11.1)/4 (44.4) | – |

| Years of nursing experience | 13.9 ± 8.4 | 17.8 ± 10.2 | 10.8 ± 4.9 | 0.006 |

| Years of nursing experience at affiliated department | 4.7 ± 4.0 | 3.7 ± 3.4 | 5.6 ± 4.2 | 0.016 |

| Childrearing or care, number/age group | 2/30s | 0 | 2/30s | – |

| Nightshifts/month, times | 5.1 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 0.478 |

| Nightshifts/survey period, times | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.013 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.8 ± 6.5 | 24.2 ± 9.0 | 21.7 ± 3.1 | 1.000 |

Mean ± standard deviation. Mann-Whitney U-test. BMI: body mass index.

2) Comparison of the basic attributes between groups

Years of nursing experience, nurses’ age, and years of nursing experience in the affiliated department were significantly higher among the participants in the high fatigue group than those in low fatigue group. The two nurses in their 30s with people in their homes who required childrearing or care were both in the low fatigue group. The number of nightshifts during the survey period was significantly higher in the high fatigue group than in low fatigue group. The number of nightshifts in the previous month and the survey month or in BMI was statistically insignificant between the two groups (Table 1).

Relationship between degree of fatigue, amount of physical activity, and sleep

1) Comparison of physical activity and sleep between groups

Table 2 shows the results on physical activity and sleep between the two groups. The mean “before” degree of fatigue for all participants was 39.8 ± 15.0, while the mean “after” score was 43.3 ± 18.9. The length of nocturnal awakening time was significantly longer in the high fatigue group compared to low fatigue group.

Table 2. Comparison of the amount of physical activity and sleep in the high fatigue group and the low fatigue group.

| Total (n = 9) |

High fatigue group (n = 4) |

Low fatigue group (n = 5) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calories spent, kcal/day | 1912.3 ± 392.7 | 1877.9 ± 401.4 | 1939.7 ± 389.2 | 0.319 |

| Time in bed, minutes | 403.9 ± 147.6 | 398.1 ± 141.8 | 408.5 ± 154.0 | 0.934 |

| Hours of sleep, minutes | 367.9 ± 139.0 | 355.5 ± 125.0 | 377.8 ± 150.3 | 0.618 |

| Length of nocturnal awakening time, minutes | 22.7 ± 20.5 | 27.5 ± 20.9 | 18.7 ± 19.5 | 0.015 |

| Number of nocturnal awakenings, minutes | 9.4 ± 6.5 | 9.3 ± 6.5 | 9.4 ± 6.5 | 0.912 |

| Sleep efficiency, % | 94.1 ± 4.9 | 93.4 ± 4.4 | 94.7 ± 5.1 | 0.089 |

| Sleep onset latency, minutes | 12.0 ± 16.9 | 14.8 ± 23.8 | 9.7 ± 7.6 | 0.692 |

Mean ± standard deviation. Mann-Whitney U-test.

2) Relationship between degree of fatigue and basic attributes, sleep, and activity index

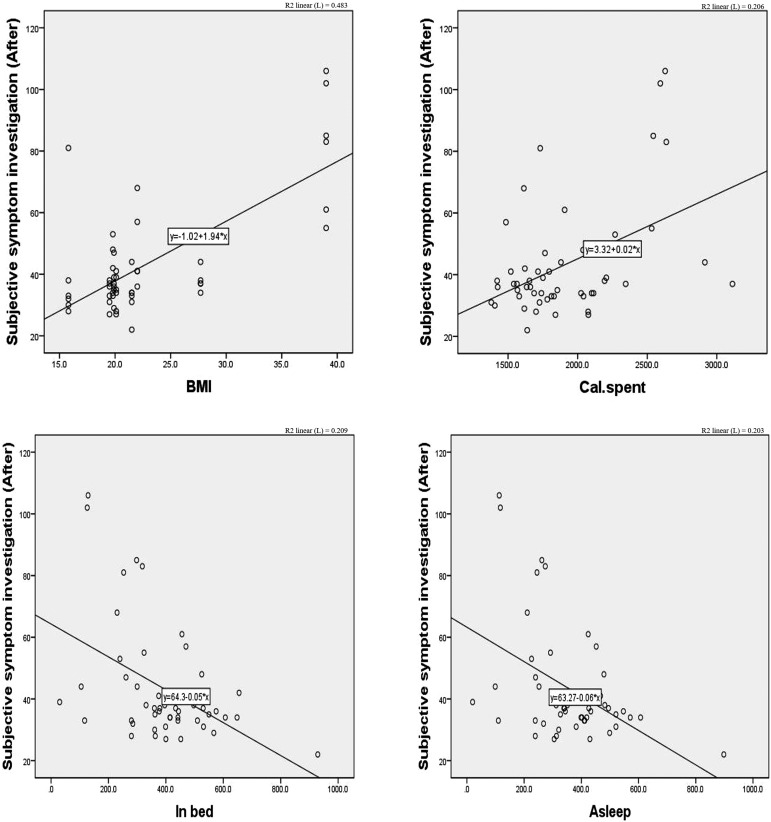

BMI (r = 0.46, p < .001) and consumed calories (r = 0.30, p < .05) and the “after” degree of subjective fatigue were significantly correlated. The time in bed (r = –0.36, p < .05) and hours of sleep (r = –0.37, p < .01) were negatively correlated (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between degree of fatigue and body mass index (top left), amount of physical activity (top right), hours in bed (bottom left), and hours of sleep (bottom right).

Comparison between the degree of fatigue, amount of physical activity, and sleep on days off and on working days

1) Degree of fatigue and amount of physical activity on days off and on working days

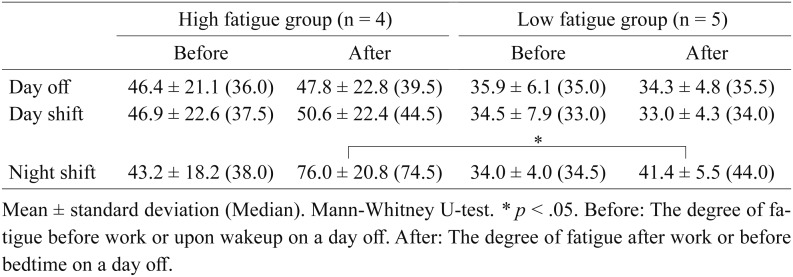

In the high fatigue group, the degree of fatigue was higher “after” than “before” both on working and on days off. The scores on the morning after the nightshift in the high fatigue group were significantly higher than in the low fatigue group (Table 3). The consumed calories were lowest on the days off for both groups: the high fatigue group was 1698.2 ± 372.5 kcal, while the low fatigue group was 1762.8 ± 263.7 kcal; however, calories consumed on days off and on working days were insignificantly different between the two groups.

Table 3. Subjective investigation scores for days off and work days in the high fatigue group and the low fatigue group.

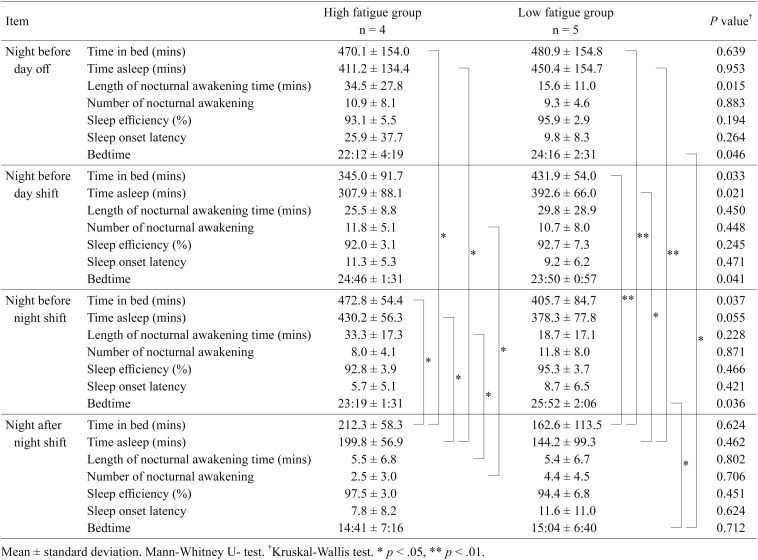

2) Degree of fatigue and sleep on days off and on working days

Bedtime on the day before days off was significantly earlier in the high fatigue group than the low fatigue group. Bedtime on the day before work days was significantly later in the high fatigue group than in the low fatigue group. Furthermore, the length of nocturnal awakening time on the day before days off was significantly longer than that of the low fatigue group. In addition, the number of hours of sleep in the high fatigue group on the day before a work day was significantly lower than in the low fatigue group. The number of nocturnal awakenings in the high fatigue group on the day before a work day was significantly higher than those on the day after a nightshift (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of sleep on days off and on work days in the high fatigue group and low fatigue group.

3) Changes in degree of fatigue and sleep before and after days off

The participants were divided into two groups: the increased fatigue degree group and the decreased fatigue degree group. This was done by using the mean ± 1/2SD of the changes of the degree of fatigue in nine participants’ days off. The bedtime of three nurses in the decreased fatigue degree group during the survey period was consistent before midnight; their sleep efficiency was high (≥ 95.5%); their sleep onset latency was short (≤ 8.5 minutes); their number of nocturnal awakenings was low (≤ 5.8); and they managed to take naps during their nightshifts. However, the three nurses with an increased fatigue degree often went to bed after midnight, got < 7 h of sleep, had a sleep efficiency of ≤ 95%, had ≥ 14 nocturnal awakenings, slept during the day on their days off, and almost never took naps during their nightshifts.

Discussion

Relationship between degree of fatigue and basic attributes, sleep, and amount of physical activity

Results revealed that age and the number of years of nursing experience, of years of nursing experience in the affiliated department, and of nightshifts worked affect nurses’ degree of fatigue.

Regarding sleep, participants in this study slept less than the average of the general Japanese population (7 h, 42 min)15). In addition, while insignificant, the hours of sleep of the high fatigue group was shorter than that of the low fatigue group. The length of nocturnal awakening time in the high fatigue group was significantly longer than of the low fatigue group; therefore, this is likely related to the degree of fatigue. In previous research16, 17), approximately half of the nurses working in a two-shift system were reported to have nocturnal awakenings, which supports the results of this study. Nocturnal awakenings are known to lengthen with age. The high fatigue group was significantly older than the low fatigue group, which is thought to have affected the length of nocturnal awakening time. Ensuring that older nurses are allocated nap time during nightshifts and considering the number of nightshifts allocated to these nurses may be a countermeasure for nurse fatigue, thus mitigating the risk of medical accidents.

Relationship between days off, degree of fatigue during shiftwork, and sleep

Inoue et al.18) reported that the process of recovery through sleep plays a key role as a bulwark to prevent the accumulation of acute fatigue turning into chronic fatigue. In this study, nurses with a high degree of fatigue may not have been sufficiently recovering from their fatigue with their nighttime sleep. Nurses in the low fatigue group maintained a consistent bedtime, irrespective of whether it was a day off or a work day, while nurses in the high fatigue group had different bedtimes on the days before days off and the days before a work day, which tended to disrupt their sleep rhythm. The degree of subjective fatigue was significantly higher in the high fatigue group on the morning after a nightshift compared to that of the low fatigue group, which suggests that nurses with a high degree of fatigue after a nightshift tended to have disrupted sleep rhythms. These results suggest that when working in a two-shift system, sleep rhythm may be related to fatigue.

This study presents the results of only nine nurses in one region and one facility; therefore, these results cannot be generalized to all nurses working in a two-shift system in Japan and should be verified with more participants in the future. In addition, we used subjective symptoms to measure fatigue and cumulative fatigue; therefore, our findings should be replicated with an objective measurement of fatigue.

Conclusion

We clarified that individual factors, such as being older, having more nursing experience, having less years of nursing experience in one’s affiliated department, working more nightshifts, and having longer nocturnal awakenings, affected nurses’ degree of subjective fatigue. The results also suggest that nurses with a high degree of fatigue have significant differences in their bedtime on days off and on work days without nightshift when compared to nurses with less fatigue, suggesting that sleep rhythm may also affect fatigue.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the MIC/SCOPE (#152301001).

The authors would like to express our appreciation to the nurses at hospital A in Hokkaido for their cooperation in this research.

References

- 1.Kango shokuin no roudou jittai chousa “Houkokusho” (Survey of nursing staff working conditions–report.) Iryo Rodo, Japan Federation of Medical Worker’s Unions. 2014; 16-22. http://irouren.or.jp/research/%E5%8A%B4%E5%83%8D%E5%AE%9F%E6%85%8B%E8%AA%BF%E6%9F%BB.pdf. (in Japanese) [accessed 24 September 2017].

- 2.Nihon no Iryou o Sukue; Kangoshoku no Kenkou to Anzen o Mamorukoto ga Kanja no Kenkou to Anzen o Mamoru (Rescuing Japanese medicine–protecting the health and safety of the nursing profession protects the health and safety of patients). Japanese Nursing Association 2011; Available from: URL https://www.nurse.or.jp/nursing/shuroanzen/jikan/pdf/sukue.pdf (in Japanese).

- 3.2012 nen Byouin ni okeru kango Shokuin Jukyuu Joukyou Chousa Sokuhou (2012 Survey on the supply and demand situation of nursing staff in hospitals–preliminary report). Public Relations Department. Japanese Nursing Association 2012; 2013: 8.(in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 4.2010 nen Byouin Kango Shoku no Yakin / Koutaisei Kinmu Jittai Chousa (2010 Survey on nightshift work and two-shift work of nursing professional in hospitals). Japanese Nursing Association 2012; 4 https://www.nurse.or.jp/nursing/shuroanzen/jikan/pdf/02_05_09.pdf (in Japanese). [accessed 24 September 2017].

- 5.Caruso CC. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil Nurs 2014; 39: 16–25. doi: 10.1002/rnj.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. The Lancet Oncology 2007; 8: 1065–1066. doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gan Y, Yang C, Tong X, et al. Shift work and diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Occup Environ Med 2015; 72: 72–78. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyazaki M, Hosona M. The relationship between sleeping patterns and fatigue among nurses on two-shift work schedules. Kobe University Graduate School of Health Sciences Bulletin 2013; 29: 1-15. http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/repository/81005507.pdf (in Japanese. Abstract in English).

- 9.Yamashita M, Yamamoto I, Shimotamari M, et al. Kangoshi no Hiroudo ni Eikyou suru Youin: Kyuukanshitu o Yuusuru Byoutou to Ippan Byoutou no Hikaku (Factors that affect the degree of fatigue in nurses: comparison of wards with emergency rooms and general wards). The 44th Proceedings of The Japan Society of Nursing. Nursing Administration 2014; 44: 122–125 (in Japanese).

- 10.Sasaki T, Matsumoto T. Prevalence of the subjective sleepiness in nurses working 16-hour night shifts. Rodo Kagaku 2013; 89: 218–224 (in Japanese, Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakinaka K, Yoshiike C, Shimomura J. Yakin-tai ni okeru Kamin Zengo no Nemuke to Hiroukan no Keikou (Trends in drowsiness and feelings of fatigue before and after a nap during nightshifts). The 43rd Proceedings of The Japan Society of Nursing, Synthetic Nursing 2013; 191–194 (in Japanese).

- 12.Ferguson T, Rowlands AV, Olds T, et al. The validity of consumer-level, activity monitors in healthy adults worn in free-living conditions: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015; 12: 42. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0201-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubo T, Tachi N, Takeyama H, et al. Characteristic patterns of fatigue feelings on four simulated consecutive night shifts by Jikaku-sho shirabe. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 2008; 50: 133–144 (in Japanese, Abstract in English). doi: 10.1539/sangyoeisei.B7008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Working Group for Occupational Fatigue. How to use “Jikaku-sho shirabe”. http://square.umin.ac.jp/of/service.html (in Japanese). [accessed 24 September 2017].

- 15.Heisei 23 nen Syakaiseikatu Kihon Tyousa (Survey on time use and leisure activities–results on leisure time) Soumushou Toukeikyoku (Statistics Bureau of Japan) 2011; http://www.stat.go.jp/data/shakai/2011/pdf/houdou2.pdf (in Japanese). [accessed 24 September 2017].

- 16.Horiguchi J, Tanaka A, Sukegawa T, et al. Koutaisei Kinmusha no Suimin kakusei Syougai to Yokuutsu ni Kansuru Kentou (Investigation on sleep arousal disorder and depression in shift workers). Seishin Igaku 1992; 34: 1113–1118 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwashita C. Investigation of the sleep actual situation by the shift working of a nurse. Memoirs Department of Health Sciences School of Medicine Kyushu University Bulletin. 2007; 8: 59–68 (in Japanese. Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue M, Kuratsune H, Watanabe Y. Hirou no Kagaku – Nemuranai Gendai Shakai he no Keishou (Science of fatigue–warning for the non-sleeping modern society). Kodansha, Tokyo, 2001; 14 (in Japanese).