ABSTRACT

Tropolonoids are important natural products that contain a unique seven-membered aromatic tropolone core and exhibit remarkable biological activities. 3,7-Dihydroxytropolone (DHT) isolated from Streptomyces species is a multiply hydroxylated tropolone exhibiting antimicrobial, anticancer, and antiviral activities. In this study, we determined the DHT biosynthetic pathway by heterologous expression, gene deletion, and biotransformation. Nine trl genes and some of the aerobic phenylacetic acid degradation pathway genes (paa) located outside the trl biosynthetic gene cluster are required for the heterologous production of DHT. The trlA gene encodes a single-domain protein homologous to the C-terminal enoyl coenzyme A (enoyl-CoA) hydratase domain of PaaZ. TrlA truncates the phenylacetic acid catabolic pathway and redirects it toward the formation of heptacyclic intermediates. TrlB is a 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonic acid-7-phosphate (DAHP) synthase homolog. TrlH is an unusual bifunctional protein bearing an N-terminal prephenate dehydratase domain and a C-terminal chorismate mutase domain. TrlB and TrlH enhanced de novo biosynthesis of phenylpyruvate, thereby providing abundant precursor for the prolific production of DHT in Streptomyces spp. Six seven-membered carbocyclic compounds were identified from the trlC, trlD, trlE, and trlF deletion mutants. Four of these chemicals, including 1,4,6-cycloheptatriene-1-carboxylic acid, tropone, tropolone, and 7-hydroxytropolone, were verified as key biosynthetic intermediates. TrlF is required for the conversion of 1,4,6-cycloheptatriene-1-carboxylic acid into tropone. The monooxygenases TrlE and TrlCD catalyze the regioselective hydroxylations of tropone to produce DHT. This study reveals a natural association of anabolism of chorismate and phenylpyruvate, catabolism of phenylacetic acid, and biosynthesis of tropolones in Streptomyces spp.

IMPORTANCE Tropolonoids are promising drug lead compounds because of the versatile bioactivities attributed to their highly oxidized seven-membered aromatic ring scaffolds. Our present study provides clear insight into the biosynthesis of 3,7-dihydroxytropolone (DHT) through the identification of key genes responsible for the formation and modification of the seven-membered aromatic core. We also reveal the intrinsic mechanism of elevated production of DHT and related tropolonoids in Streptomyces spp. The study on DHT biosynthesis in Streptomyces exhibits a good example of antibiotic production in which both anabolic and catabolic pathways of primary metabolism are interwoven into the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. Furthermore, our study sets the stage for metabolic engineering of the biosynthetic pathway for natural tropolonoid products and provides alternative synthetic biology tools for engineering novel tropolonoids.

KEYWORDS: Streptomyces, antibiotic, biosynthetic gene cluster, chorismate, natural products, phenylacetic acid, tropolone

INTRODUCTION

The tropolonoid family of natural products, isolated from plants, fungi, and bacteria, is characterized by the presence of a cyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone moiety, a rare seven-membered nonbenzenoid aromatic ring named tropone (1). Hydroxylated tropones (i.e., tropolones) are known for their diverse bioactivities. Colchicine, β-thujaplicin (hinokitiol), stipitatic acid, and tropolone itself are the earliest reported representatives and were discovered from Colchicum species, Thuja plicata (Chamaecyparis taiwanensis), Talaromyces stipitatus, and Pseudomonas lindbergii ATCC 31099, respectively (1). Even very simple monocyclic tropolones exhibit broad bioactivities. For example, as the simplest tropolone, tropolone itself is used as an iron transporter in serum-free medium for animal cell culturing (3), while it was discovered as a virulent factor of the plant pathogen Burkholderia plantarii, causing rice seedling blight (4). The α-hydroxyl group is necessary for the ion-chelating and biological activities of tropolone. 3,7-Dihydroxytropolone (compound 1 [see Fig. 1A]), isolated from Streptomyces tropolofaciens, is a multiply hydroxylated tropolone exhibiting strong antimicrobial, antitumor, and antiviral activities (5). The contiguous array of at least three oxygen atoms (ketone/hydroxyl) and the seven-membered aromatic ring are both essential for the broad bioactivities of compound 1 (6, 7). Interest in the potential bioactivities and unusual structure of compound 1 has generated a number of chemical synthesis studies focused on the derivatization of tropolone, as well as studies supporting tropolone as a very promising therapeutic drug lead (2, 8–10).

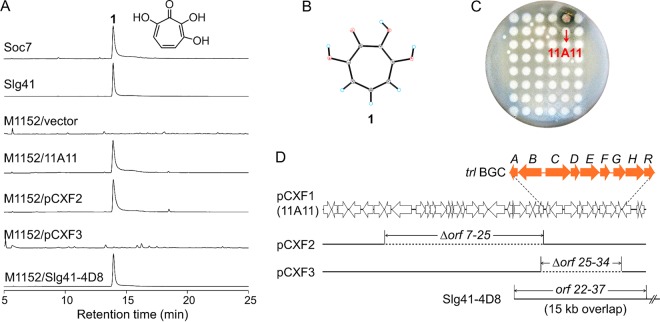

FIG 1.

Identification of 3,7-dihydroxytropolone (compound 1) and its biosynthetic gene cluster. (A) HPLC analysis of the production of compound 1 in two natural Streptomyces strains, S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 and S. luteogriseus Slg41, and in heterologous expression strains. The structure of compound 1 is shown at the upper right. M1152, S. coelicolor M1152; vector, pJTU2554. Compound 1 was eluted at 14 min in the HPLC, as shown. HPLC was monitored at 254 nm. (B) X-ray crystal structure of compound 1. (C) Cloning of the BGC of compound 1 using the bioactivity-guided library expression and analysis (LEXAS) approach. Cosmid clone 11A11 was identified by its ability to inhibit the growth of B. subtilis. (D) DNA inserts of the cosmids and derivatives carrying chromosomal regions surrounding the trl BGC. Wide arrows represent open reading frames; solid lines, DNA inserts; dotted lines, deleted regions. Only part of the Slg41-4D8 insert is shown.

Previous biosynthetic studies of tropolonoids have revealed diverse routes for the formation of the tropone ring, all involving a key ring expansion step from a benzenoid framework (11). In Talaromyces stipitatus, stipitatic acid is produced through a nonreducing polyketide synthase (NR-PKS) pathway. The tropolone core of stipitatic acid is generated via a pinacol-type rearrangement catalyzed by a nonheme Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase, TropC (12). In prokaryotes, two pathways have been proposed for the biosynthesis of tropolonoids. A type II polyketide assembly line followed by predicted complex oxidative rearrangements is responsible for the biosynthesis of rubrolones in Streptomyces spp. (13). Escherichia coli is not known to produce tropolonoid, but it has an unorthodox aerobic phenylacetic acid (PAA) catabolic pathway that degrades PAA via a ring epoxide-oxepin rearrangement followed by PaaZ-catalyzed hydrolytic ring cleavage and oxidation. In vitro data suggested that when the oxidation function of PaaZ was deficient, the aerobic PAA catabolic pathway was truncated and branched to the production of 2-hydroxycyclohepta-1,4,6-triene-1-formyl-CoA, which is proposed as a long-sought seven-membered carbocyclic intermediate for the biosynthesis of bacterial tropolonoids (14, 15). This aerobic PAA degradation pathway is widespread in bacteria (15) and was recently found to be required for the biosynthesis of tropodithietic acid (TDA) and roseobacticide in Phaeobacter inhibens (16, 17).

Streptomyces species are the producers of many important secondary metabolites. Besides the polyketide-derived multicyclic tropolonoids, such as rubrolones, some Streptomyces strains produce small tropolonoids, such as compound 1 (5). During our ongoing antibiotic-screening program, we discovered that two Streptomyces strains, Streptomyces cyaneofuscatus Soc7 and Streptomyces luteogriseus Slg41, produced compound 1 at very high titers compared to those reported in the literature. In this work, we sought to study the biosynthesis of compound 1 to reveal the formation of the tropone core, the multiple hydroxylations on the seven-membered aromatic ring, and the mechanism of the high yield of compound 1.

RESULTS

Identification of the biosynthetic gene cluster of 3,7-dihydroxytropolone from Streptomyces spp.

S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 and S. luteogriseus Slg41 produced 3,7-dihydroxytropolone (compound 1) (Fig. 1A) at high titers (380 and 230 mg/liter, respectively), which were >10,000-fold higher than the titer reported for S. tropolofaciens No. K611-97, the species from which compound 1 was first identified (5). The identity of compound 1 was confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and X-ray crystallography (Fig. 1B). To isolate the biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) for compound 1, we used a recently established high-throughput library expression and bioactivity-guided screening approach, LEXAS (18). LEXAS screening of the genomic library of S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 yielded a positive cosmid clone, 11A11, whose exconjugant on the fermentation agar petri dish produced a clear zone of Bacillus subtilis growth inhibition (Fig. 1C). To confirm the screening result, cosmid DNA of 11A11 was introduced into Streptomyces coelicolor M1152 and S. coelicolor M1154 for heterologous expression. The production of compound 1 was detected in the resulting exconjugants by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis; S. coelicolor M1152/11A11 is shown as an example in Fig. 1A. Heterologous production of compound 1 reached high titers of 606 and 498 mg/liter in S. coelicolor M1152/11A11 and M1154/11A11, respectively. These results indicated that 11A11 contained the complete BGC for the heterologous biosynthesis of compound 1. For consistency with its subsequently derived constructs, cosmid 11A11 was named pCXF1. In subsequent genetic studies, S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF1 was used as the wild type and the parent strain for the construction of large-fragment deletion and in-frame deletion mutants.

Cosmid pCXF1 was sequenced, and bioinformatics analysis of the 39-kb insert revealed 37 open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1D), including two clusters of genes related to riboflavin biosynthesis (orf8 to orf18) and aromatic metabolism (orf26 to orf34), respectively. To identify genes responsible for the biosynthesis of compound 1, two regions were deleted from pCXF1: one deletion, spanning orf7 to orf25, removed the riboflavin biosynthesis region and resulted in pCXF2, and the other deletion, spanning orf25 to orf34, removed the aromatic metabolism region and resulted in pCXF3 (Fig. 1D). HPLC analysis indicated that the production of compound 1 was maintained in S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF2 but not in S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF3 (Fig. 1A), suggesting that the genes missing from pCXF3 were required for heterologous production of compound 1. In addition, another compound 1-producing clone, Slg41-4D8, was obtained from the LEXAS screening of the S. luteogriseus Slg41 genomic library. Sequencing revealed that Slg41-4D8 had a 15-kb DNA overlapping and identical with the orf22-to-orf37 region of pCXF1 (Fig. 1D). These results indicated that orf1 to orf25 were not required, and that orf26 to orf34 were required, for the production of compound 1. Three other genes at the right boundary of pCXF1, orf35 to orf37, encode transcriptional regulators and thus are not directly involved in the biosynthesis of compound 1.

Bioinformatics analysis of the trl gene cluster.

The nine genes required for the biosynthesis of compound 1 were renamed trlABCDEFGHR. These trl genes are organized into three putative operons: trlAB, trlCDEF, and trlGHR (Fig. 1D). TrlA contains a MaoC dehydratase domain and is similar to the enoyl coenzyme A (enoyl-CoA) hydratase domain of E. coli bifunctional protein PaaZ (similarity, 47%; identity, 31%). E. coli PaaZ is a key catabolic enzyme involved in the aerobic degradation of PAA. PaaZ contains an N-terminal aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) domain and a C-terminal (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase domain (ECH). PaaZ ECH is responsible for the hydrolytic ring cleavage of oxepin-CoA to generate a highly reactive 3-oxo-5,6-dehydrosuberyl-CoA semialdehyde in E. coli (14). The ALDH domain is responsible for further oxidation of that semialdehyde into 3-oxo-5,6-dehydrosuberyl-CoA. With the help of other catabolic enzymes, 3-oxo-5,6-dehydrosuberyl-CoA is broken down into two acetyl-CoA molecules and one succinyl-CoA molecule (15). In the absence of a functional ALDH domain, the aerobic PAA degradation pathway is blocked at the semialdehyde (14). In this case, the semialdehyde undergoes spontaneous intramolecular Knoevenagel condensation and dehydration to yield 2-hydroxycyclohepta-1,4,6-triene-1-formyl-CoA (14), which is proposed to be the long-sought intermediate for the production of seven-membered carbocyclic antibiotics, such as TDA and roseobacticide in P. inhibens (14, 16, 17). Interestingly, there is no ALDH domain in TrlA, implying a truncated PAA catabolic pathway.

TrlB is homologous to 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonic acid-7-phosphate (DAHP) synthase, catalyzing the condensation of phosphoenolpyruvate and d-erythrose-4-phosphate to generate DAHP, which is the first committed step of the shikimate biosynthetic pathway. TrlH is a bifunctional protein bearing an N-terminal prephenate dehydratase (PDT) domain and a C-terminal chorismate mutase (CM) domain, which exhibits an unusual domain arrangement, opposite that of the bifunctional P-protein in Gram-negative bacteria (19). P-protein bears an N-terminal CM domain and a C-terminal PDT domain that convert chorismate into prephenate and phenylpyruvate sequentially. The trlG and trlR genes form one operon with trlH. TrlG is an unknown protein bearing an AfsA-like hotdog-fold protein domain, while TrlR is a TetR family transcriptional regulator.

TrlC and TrlD are homologous to the HpaB superfamily oxidase component and the HpaC superfamily flavin reductase component of 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase, respectively. HpaB and HpaC in E. coli make up a two-component monooxygenase with aromatic hydroxylase activity (20). Therefore, TrlC and TrlD were proposed to function as a two-component monooxygenase named TrlCD. TrlE is a monooxygenase homolog of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent 6-hydroxynicotinate 3-monooxygenase (similarity, 46%; identity, 33%) (21). The trlF gene product is an unknown protein similar to the carnitine operon protein CaiE of Salmonella enterica (similarity, 74%; identity, 58%) and E. coli K-12 (similarity, 75%; identity, 55%) (22) and less similar to the unknown protein PaaY of the PAA degradation gene cluster in E. coli (similarity, 65%; identity, 50%) (23). Information about the Trl proteins encoded by the trl BGC, including their deduced functions, is summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Deduced functions of gene products of the trl BGCa

| Protein (aa) | Proposed function | Homolog (sequence ID in Swiss-Prot, origin) | Identity/similarity (%) | Conserved domain, accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TrlA (159) | Enoyl-CoA hydratase (PaaZ-ECH) | P77455.1, Escherichia coli K-12 | 31/47 | MaoC, COG2030 |

| TrlB (484) | DAHP synthase | P80574.3, Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) | 64/76 | DAHP_synth_2, PF01474 |

| TrlC (530) | Monooxygenase, oxidase component | Q8RQQ0.2, Rhodococcus sp. | 57/71 | HpaB, PF03241 |

| TrlD (185) | Monooxygenase, flavin reductase component | Q8RQP9.2, Rhodococcus sp. | 33/46 | Flavin_reduct, smart00903 |

| TrlE (400) | Monooxygenase | Q88FY2.1, Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | 31/46 | Salicylate_mono, TIGR03219 |

| TrlF (203) | Unknown | Q8Z9L6.1, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi | 58/74 | LbH_paaY_like, cd04745 |

| TrlG (253) | Unknown | SER21282.1, Actinokineospora terrae | 42/56 | Hotdog family, PF03756 |

| TrlH (402) | Bifunctional prephenate dehydratase–chorismate mutase | B2HMM5.1, Mycobacterium marinum | 40/51 | PDT, PF00800; CM_2, PF01817 |

| TrlR (209) | TetR family transcriptional regulator | WP_030238659.1, Streptomyces | 75/78 | TetR_N, PF00440 |

The GenBank accession number of the trl BGC is MF955860.

TrlA truncates the endogenous PAA catabolic pathway and directs it toward the biosynthesis of compound 1.

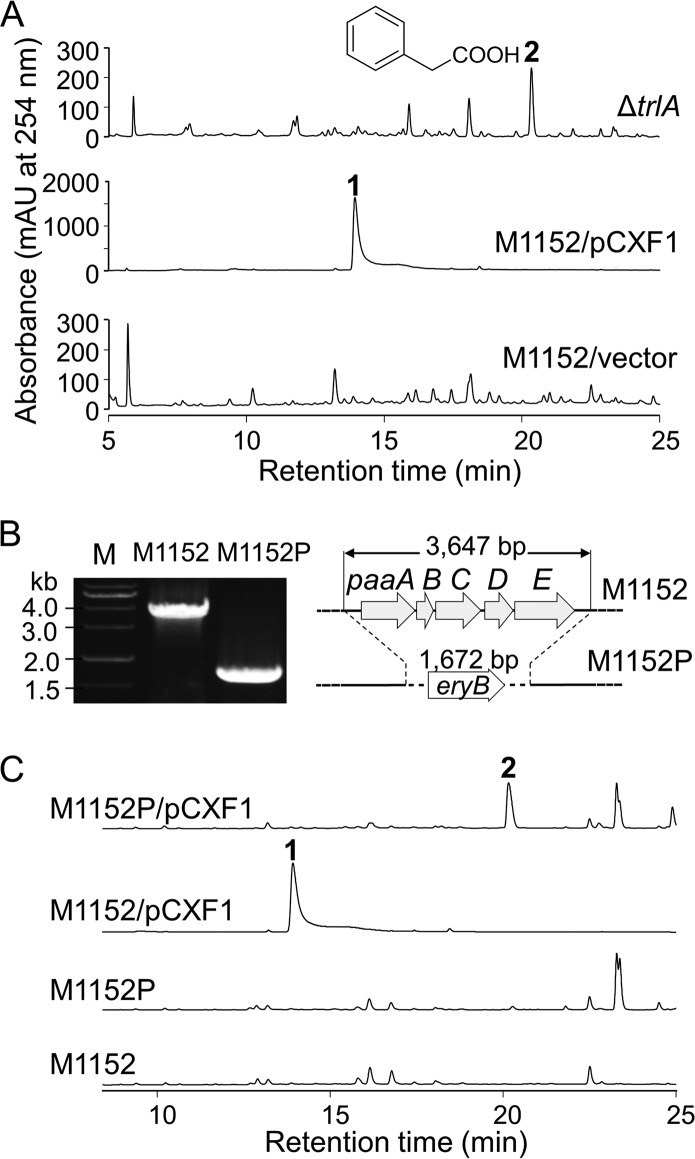

To determine whether the paaZ ECH-homologous gene trlA is involved in the biosynthesis of compound 1, trlA was deleted from pCXF1 to produce pCXF4, which was introduced into S. coelicolor M1152 to yield the in-frame deletion mutant S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF4 (i.e., the ΔtrlA mutant) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). HPLC-mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of the ΔtrlA ferment revealed that compound 1 production was abolished and that PAA (compound 2) accumulated (Fig. 2A), indicating that trlA is required for compound 1 production and implying that compound 1 originates from compound 2. This result also implied that TrlA directs the cellular PAA catabolic pathway toward the biosynthesis of compound 1, as proposed for other tropolonoids (14). However, there is no other gene in the trl BGC that shares similarity with the early bacterial aerobic PAA catabolic genes. We therefore speculated that the endogenous paa genes from the S. coelicolor surrogate host participated in the biosynthesis of compound 1—for example, SCO7471 to SCO7475, which form an operon orthologous to the E. coli paaABCDE operon encoding subunits of the monooxygenase (epoxidase) complex responsible for the oxidation of PAA-CoA to epoxy-ring-1,2-phenylacetyl-CoA. To test this hypothesis, SCO7471 to SCO7475 were deleted from the S. coelicolor M1152 chromosome by gene replacement, resulting in the paaABCDE-disrupted strain S. coelicolor M1152P (Fig. 2B). As expected, compound 2 accumulated in S. coelicolor M1152P/pCXF1 instead of compound 1 (Fig. 2C), supporting the notion that the host aerobic PAA catabolic pathway takes part in the biosynthesis of compound 1. Other paa-homologous genes in the S. coelicolor genome, including those encoding the PAA-CoA ligase PaaK (SCO7469) and enoyl-CoA isomerase PaaG (SCO5144), which catalyze early steps of the aerobic PAA catabolic pathway (15), should also be involved in the biosynthesis of compound 1.

FIG 2.

Involvement of the PAA catabolic genes trlA and paaABCDE in the production of compound 1. (A) HPLC analysis of the ΔtrlA mutant (S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF4). (B) Verification of the paaABCDE gene replacement mutant by PCR and schematic representation of the wild-type and mutated paaABCDE loci. (C) HPLC analysis of the paaABCDE gene replacement mutant M1152P/pCXF1. HPLC was monitored at 254 nm.

TrlB, TrlG, TrlH, and TrlR enhance de novo synthesis of phenylpyruvate or PAA and lead to the high yield of compound 1 in Streptomyces.

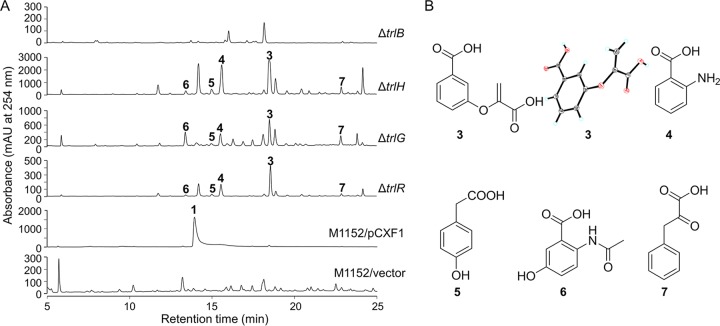

The sequences of TrlB and TrlH suggested their key roles in the supply of PAA precursor for the biosynthesis of compound 1. To investigate their roles in compound 1 biosynthesis, trlB and trlH were deleted from pCXF1, and the resulting plasmids were introduced into S. coelicolor M1152 to yield two in-frame deletion mutant strains, the ΔtrlB and ΔtrlH strains, respectively. HPLC analysis revealed a deficiency in compound 1 production in the two mutants (Fig. 3). In addition, the ΔtrlH mutant accumulated a large amount of 3-[(1-carboxyethenyl)oxy]benzoic acid (compound 3) and smaller amounts of other chorismate-derived metabolites, such as anthranilic acid (compound 4), 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (compound 5), 2-acetamido-5-hydrobenzoic acid (compound 6), and phenylpyruvic acid (compound 7) (Fig. 3). The chemical identities of compounds 3 to 7 were determined by HRMS and/or NMR analyses (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). These aromatic compounds could be derived from the common precursor chorismate, through different pathways (19, 24–26). These findings supported the notion that TrlB and TrlH contributed to the biosynthesis of compound 1 by providing a rich source of precursor through boosting the shikimate pathway (by TrlB) and converting chorismate to compound 7 (by TrlH).

FIG 3.

Metabolic analysis of the ΔtrlB, ΔtrlH, ΔtrlG, and ΔtrlR mutants and the chemical structures of the accumulated compounds. (A) HPLC analysis of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF1 and trl gene deletion mutants. An equal volume of extract of each mutant was injected for HPLC. Note that the y axis scales are different for each mutant. Vector, pJTU2554. (B) Structures of the accumulated compounds. The X-ray crystal structure of compound 3 is also shown. The products identified were as follows: 3-[(1-carboxyethenyl)oxy]benzoic acid (compound 3), anthranilic acid (compound 4), 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (compound 5), 2-acetoamido-5-hydroxybenzoic acid (compound 6), and phenylpyruvate (compound 7).

To further confirm the contribution of TrlB and TrlH to the production of compound 7, trlB and trlH were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-induced E. coli cultures were extracted and were analyzed by HPLC. Massive accumulation of compound 7 was observed in the extract of E. coli expressing TrlB alone (4.02 mg/liter) or TrlB and TrlH together (6.72 mg/liter), in contrast to accumulation in the vector control strains (0.046 mg/liter and 0.042 mg/liter) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). These data supported the notion that TrlB and TrlH enhanced the biosynthesis of compound 7 and thereby contributed to the high yield of compound 1 in the heterologous hosts and in the natural strains S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 and S. luteogriseus Slg41. These two natural strains produced compound 1 at a >10,000-fold-higher yield than that of the producer originally isolated, S. tropolofaciens No. K611-97, from which 4 mg of the compound was purified from 208 liters of liquid culture (5). To determine whether compound 7 is the on-pathway intermediate to compound 1, a biotransformation experiment was performed by feeding compound 7 to the ΔtrlB mutant. As expected, the production of compound 1 was clearly observed in the HPLC (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

In-frame deletion mutants S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF10 (i.e., the ΔtrlG mutant) and S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF12 (i.e., the ΔtrlR mutant) were constructed, and HPLC analysis indicated that these mutants also lacked compound 1 production and accumulated compounds 3 to 7. Both the ΔtrlG mutant and the ΔtrlR mutant showed HPLC profiles similar to that of the ΔtrlH mutant, except that the absorbance peaks in the ΔtrlG and ΔtrlR mutants were much lower than their counterparts in the ΔtrlH mutant (Fig. 3A). These results suggested that TrlR regulated the expression of TrlG and TrlH and that TrlG played a pivotal role in precursor supply for the biosynthesis of compound 1.

Monooxygenases TrlE and TrlCD catalyze the site-specific hydroxylations on the tropone ring.

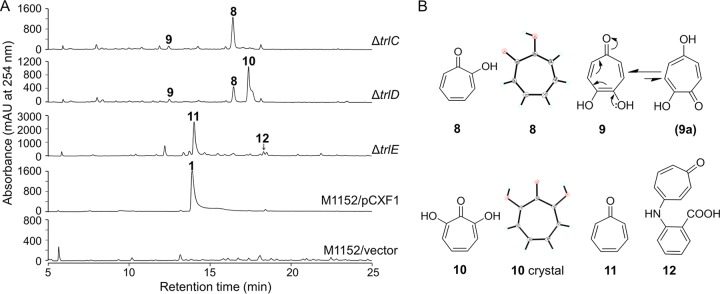

To investigate the hydroxylation modifications on the tropone ring that lead to the multiply hydroxylated product compound 1, the two-component monooxygenase genes trlC and trlD and the other monooxygenase gene, trlE, were deleted in pCXF1 and were introduced into S. coelicolor M1152 to yield three in-frame deletion mutants: S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF6 (ΔtrlC), S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF7 (ΔtrlD), and S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF8 (ΔtrlE). The ΔtrlC mutant lost the production of compound 1 and accumulated two compounds that were identified as tropolone (compound 8) and 4,5-dihydroxytropone (compound 9) through X-ray crystallography, HRMS, and NMR analyses (Fig. 4; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). Compound 9 may be regarded as a tautomer of 2,5-dihydroxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone (compound 9a), which is a synthesized chemical (27). The ΔtrlD mutant also lost the production of compound 1 and accumulated compounds 8 and 9. In addition, this mutant accumulated another major component, which was characterized as 7-hydroxytropolone (compound 10) through HRMS, X-ray crystallography, and NMR analyses (Fig. 4; also Table S2). Mutation of trlE abolished the production of compound 1, and the ΔtrlE mutant accumulated two different compounds, identified as tropone (compound 11) and 2-(1,3,6-cycloheptatriene-5-oxo)-aminobenzoic acid (compound 12) (Fig. 4; also Table S2). Compound 12 is a novel tropone natural product. The production of compound 9 in both the ΔtrlC and ΔtrlD mutants implied the presence of an unknown hydroxylation enzyme. The production of compound 12 in the ΔtrlE mutant is also a mystery, although a substitution by anthranilic acid at C-4 or C-5 is possible, owing to the cycloheptatrienylium ion nature of tropone (28). Nevertheless, compounds 9 and 12 are minor components and are probably shunt products.

FIG 4.

Metabolic analysis of the ΔtrlC, ΔtrlD, and ΔtrlE mutants and chemical structures of the accumulated compounds. (A) HPLC analysis of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF1 and trl gene deletion mutants. Vector, pJTU2554. (B) Structures of the accumulated compounds. The X-ray crystal structures of compounds 8 and 10 are also shown. The products identified were as follows: tropolone (compound 8), 4,5-dihydroxytropone (compound 9), 7-hydroxytropolone (compound 10), tropone (compound 11), and 2-(1,3,6-cycloheptatriene-5-oxo)-aminobenzoic acid (compound 12). Compounds 9 and 12 are discovered here as natural products.

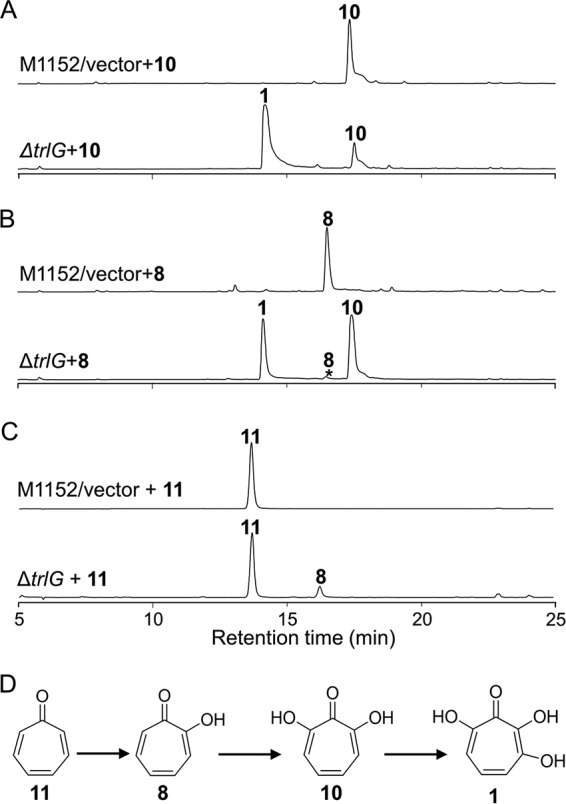

To determine whether compounds 11, 8, and 10 are real biosynthetic intermediates, biotransformation experiments were performed by feeding these compounds to the ΔtrlG mutant and/or incubating them with cell extracts of the ΔtrlG mutant. The ΔtrlG mutant carries functional genes for the production of TrlC, TrlD, and TrlE. Feeding compound 10 to the ΔtrlG mutant resulted in the production of compound 1, suggesting that compound 1 is synthesized from the hydroxylation of C-3 on compound 10 (Fig. 5A). Feeding compound 8 to the ΔtrlG mutant resulted in the production of compound 10, and prolonged incubation resulted in the production of compound 1 (Fig. 5B), suggesting that compound 10 is synthesized from the hydroxylation at C-7 of compound 8. However, no biotransformation was observed for compound 11 in the feeding experiment, which could be explained by the poor uptake of compound 11 by bacterial cells. To overcome the potential uptake problem with compound 11, a cell extract of the ΔtrlG mutant was incubated with compound 11. As expected, conversion of compound 11 to compound 8 was clearly observed in the HPLC (Fig. 5C). These results indicated that compound 1 is produced from compound 11 via successive hydroxylations, first at its C-2 site to yield compound 8, in a reaction catalyzed by TrlE, and then at its C-7 and C-3 sites to yield compounds 10 and 1, in reactions catalyzed by the two-component monooxygenase TrlCD (Fig. 5D).

FIG 5.

Transformation of tropone or tropolones by feeding to Streptomyces cultures or by incubation with Streptomyces cell extracts. (A) HPLC detection of the biotransformation of compound 10 after feeding to a culture of the ΔtrlG mutant (S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF10) or the vector control. HPLC was monitored at 254 nm. (B) HPLC detection of the biotransformation of compound 8 after feeding to a culture of the ΔtrlG mutant or the vector control. HPLC was monitored at 254 nm. (C) HPLC detection of the biotransformation of compound 11 after incubation with a cell extract of the ΔtrlG mutant or the vector control. HPLC was monitored at 300 nm. (D) Schematic representation of biotransformations of compound 11 through compounds 8 and 10 to compound 1.

To confirm that TrlE catalyzes the conversion of compound 11 to compound 8, a biotransformation experiment was conducted with cell extracts of an E. coli strain expressing TrlE. The E. coli cell extract was incubated with compound 11 at 30°C for 2 h. Conversion of compound 11 to compound 8 was clearly observed from the HPLC (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), confirming that the monooxygenase TrlE was responsible for C-2 hydroxylation on compound 11 to generate compound 8. To confirm that TrlCD catalyze the conversions of compound 8 to compound 10 and of compound 10 to compound 1, TrlC and TrlD were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). The cell extracts were incubated with compound 8 or compound 10 at 30°C for 2 h. A stepwise conversion of compound 8 to compound 10 and compound 1 was clearly observed from the HPLCs (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), confirming that the two-component monooxygenase TrlCD was responsible for the C-7 and C-3 hydroxylations on compound 8 to give the final product, compound 1.

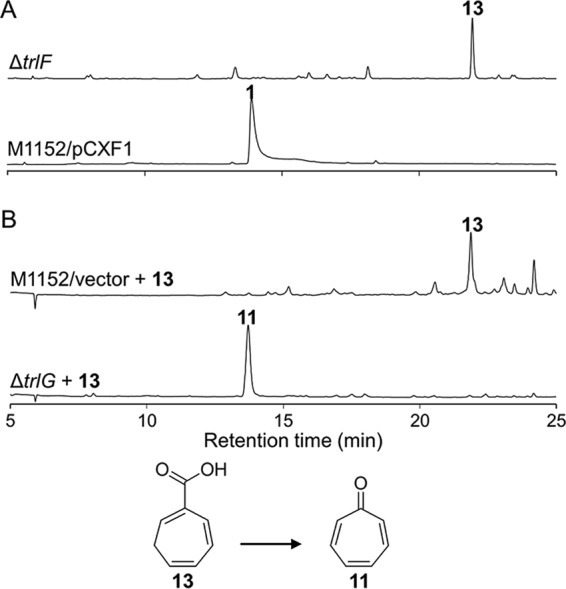

Identification of 1,4,6-cycloheptatriene-1-carboxylic acid as a key intermediate for the biosynthesis of compound 1.

The trlF deletion also resulted in the abolishment of compound 1. To our surprise, the ΔtrlF mutant (S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF9) accumulated a novel compound (Fig. 6A), which was elucidated as 1,4,6-cycloheptatriene-1-carboxylic acid (compound 13) using HRMS and NMR analyses (Table S2 in the supplemental material). To determine whether compound 13 is a biosynthetic intermediate for compound 1, a cell extract of the ΔtrlG mutant was mixed with compound 13 as a substrate and was incubated at 30°C for 2 h. HPLC analysis of the cell-free reaction mixture indicated that compound 13 was completely converted to compound 11 (Fig. 6B), suggesting that compound 13 is a bona fide biosynthetic intermediate of compound 1.

FIG 6.

HPLC analysis of the ΔtrlF mutant and biotransformation of the accumulated compound 13. (A) HPLC analysis of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF1 and the trlF gene deletion mutant (S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF9). HPLC was monitored at 254 nm. (B) HPLC detection of the biotransformation of compound 13 (cyclohepta-1,4,6-triene-1-carboxylic acid) after incubation with a cell extract of the ΔtrlG mutant (S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF10) or the vector control. HPLC was monitored at 300 nm.

DISCUSSION

The involvement of the PaaZ ECH and PaaABCDE homologs in the biosynthesis of compound 1 clearly supports a PAA origin for compound 1 in Streptomyces spp., a feature similar to that in P. inhibens, in which a specific didomain enzyme, PaaZ2, was found to be required for the production of TDA and roseobacticide (16, 17). PaaZ2 is a didomain protein homologous to E. coli PaaZ, but it carries C295R and E256C mutations in the active sites and therefore likely inactivates its ALDH function (16, 17). In E. coli, when the oxidization activity of the PaaZ ALDH domain was abolished, PAA degradation was blocked, and the truncated PAA catabolism produced 2-hydroxycyclohepta-1,4,6-triene-1-formyl-CoA (14). This CoA thioester was proposed as a plausible biosynthetic intermediate for the production of TDA and other bacterial tropolonoids (14). Our genetic data suggested that a truncated PAA degradation pathway is required to construct the seven-membered carbocyclic scaffold of compound 1 in Streptomyces spp., where a single domain (ECH) protein, TrlA, plays a pivotal role in redirecting the degradation pathway.

The DAHP synthase gene homolog TrlB and the bifunctional protein TrlH (with prephenate dehydratase and chorismate mutase fused) are key enzymes of the chorismate and phenylpyruvate biosynthetic pathways. The involvement of TrlB and TrlH in the production of compound 1 also supported the notion that compound 1 is derived from compound 2, which is, however, supplied through anabolic reactions in this case, and indicated a strong connection between primary and secondary metabolism. Obviously, the trlB and trlH genes accounted for the high yield of compound 1 in Streptomyces spp. by supplying sufficient amounts of PAA precursor. The chromosomal genes of the heterologous expression host S. coelicolor also encode TrlB- and TrlH-like enzymes for the synthesis and utilization of chorismate, i.e., DAHP synthase (SCO2115), prephenate dehydratase (SCO3962), and chorismate mutase (SCO1762, SCO2019, and SCO4784), which are crucial for the normal growth of the strain. Interestingly, however, both the ΔtrlB and the ΔtrlH mutant lost production of compound 1, indicating that the genes mentioned above do not contribute significantly to the production of compound 1.

Notably, TrlH is a unique bifunctional PDT-CM protein in Gram-positive bacteria, and its domain organization contrasts with that of the bifunctional P-protein (CM-PDT) of Gram-negative bacteria (19). P-protein is a key regulation node for fine-tuning metabolic flow into the phenylalanine synthetic pathway in bacteria. P-protein is allosterically retroinhibited by l-Phe, and the two highly conserved motifs GAL/V and ERRP have been identified as essential for l-Phe binding to the regulatory domain (19). Interestingly, TrlH does not contain any conserved l-Phe binding motifs. However, several benzenoids found in the ΔtrlH mutant, such as compounds 3 to 6, were also found to be accumulated in another mutant, the ΔtrlG mutant, implying that TrlH may be subjected to feedback inhibition by a yet unknown metabolite. TrlG is an unknown protein required for precursor supply for the biosynthesis of compound 1. TrlG might act after TrlH, although its exact biochemical role needs further characterization, since limited information was deduced from the sequence.

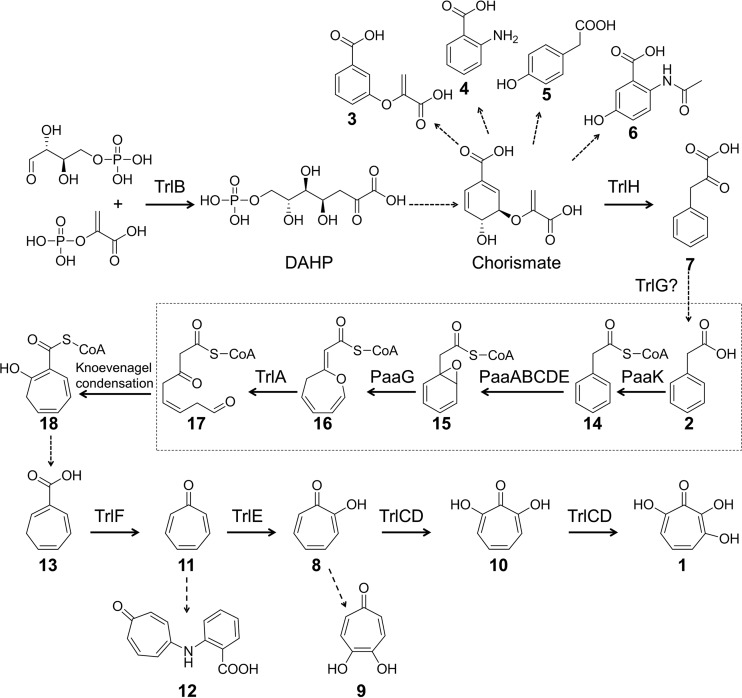

On the basis of our genetic, natural-product chemistry, and biotransformation data, we show the proposed pathway for the biosynthesis of compound 1, which interweaves PAA biosynthesis, PAA catabolism, and cycloheptatriene ring decorations, in Fig. 7. The trl BGC encodes two key enzymes (TrlB and TrlH) for the biosynthesis of compound 2 and one enzyme (TrlA) to direct a branch of the PAA catabolic pathway toward the formation of a seven-membered carbocyclic intermediate(s). Other genes for PAA biosynthesis and catabolism are encoded by chromosomal regions beyond the trl gene cluster. In this way, the host's anabolic pathways of chorismate and phenylpyruvate are reinforced, and the PAA catabolic pathway is redirected to the prolific production of the heptacyclic intermediate compound 13. At last, four Trl proteins (TrlF, TrlE, TrlC, and TrlD) modify compound 13 sequentially, leading to the formation of compound 11, compound 8, compound 10, and the final product, compound 1. In this pathway, tropolone (compound 8) is synthesized via a site-specific hydroxylation of tropone (compound 11), a process different from that for stipitatic acid in fungi, where the hydroxyl group is part of the seven-membered carbocyclic intermediate (12).

FIG 7.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway for compound 1 in Streptomyces spp. The partial aerobic PAA catabolic pathway is boxed. Steps catalyzed by other enzymes of the host are indicated by dashed arrows. TrlB catalyzes the first step of the shikimate pathway, thereby enhancing chorismate biosynthesis. TrlH catalyzes the formation of phenylpyruvate from chorismate, and TrlG is probably involved in the formation of PAA from phenylpyruvate. The host's PaaK, PaaABCDE, and PaaG proteins catalyze the formation of phenylacetyl-CoA (compound 14), ring-1,2-epoxyphenylacetyl-CoA (compound 15), and 2-oxepin-2(3H)-ylideneacetyl-CoA (compound 16), respectively (14). TrlA catalyzes the formation of 3-oxo-5,6-dehydrosuberyl-CoA semialdehyde (compound 17), whose further degradation is prevented by the natural absence of a PaaZ ALDH domain from TrlA, allowing the spontaneous formation of 2-hydroxycyclohepta-1,4,6-triene-1-formyl-CoA (compound 18) via Knoevenagel condensation. The steps after Knoevenagel condensation leading to the formation of compound 13 are not clear yet but possibly involve reduction, dehydration, and thioester hydrolysis. Finally, the sequential hydroxylations on compound 11 at C-2, C-7, and C-3 are catalyzed by TrlE and TrlCD and result in the formation of compound 1.

The chemical synthesis of compound 13 has been reported previously (29), and here we show its discovery as a natural product. We also discovered compound 13 as a novel seven-membered carbocyclic intermediate for the biosynthesis of tropone, tropolone, hydroxytropolones, and probably other heptacyclic metabolites found in actinomycetes, such as tropone hydrate, cyclohept-4-enone, and cyclohept-4-enol (30). Compound 13 might also be a biosynthetic intermediate of heptacyclic metabolites in other bacteria. Indeed, it has been proposed for the biosynthesis of ω-cycloheptyl fatty acids in Alicyclobacillus cycloheptanicus (31), and tropone (compound 11) has been reported from Azoarcus evansii and marine bacteria of the Roseobacter clade as a natural product or shunt (16, 32, 33). Given the wide distribution of paa genes and trlF homologs in bacteria, the distribution and diversity of tropone-derived metabolites may have been underestimated. Furthermore, the trl genes found in this study could be used to discover new tropolonoids, for example, via synthetic biology technologies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli DH10B was used as a host for general DNA cloning, and E. coli XL1-Blue MR/pUZ8002 was used for construction of the cosmid genomic library (34). E. coli BW25113/pIJ790 was used for λ Red-mediated PCR targeting to construct gene disruption mutants (35, 36). E. coli BT340 (E. coli DH5α/pCP20) was used for the construction of in-frame deletion mutants using flippase recombination enzyme (FLP)-mediated site-specific recombination (36). E. coli ET12567/pUB307 was used as the helper strain to facilitate E. coli–Streptomyces intergenus triparental mating (37), and E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) was used for protein expression. S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 and S. luteogriseus Slg41 were obtained from the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC AA92032 and CCTCC AA92034). Streptomyces lividans SBT5 (38), S. coelicolor M1152, and S. coelicolor M1154 (39) were used as surrogate hosts for expressing the entire cosmid genomic library, the tropolone BGC, and its gene disruption variants.

pJTU2554 (40) carrying an origin of transfer (oriT), an integrase gene (int), and a site of integration (attPϕC31) was used as the cosmid vector for constructing the cosmid genomic library. pJTU2554-derived plasmids (cosmids and related gene disruption mutants) can be mobilized into Streptomyces spp. and integrated site-specifically into the chromosome at the attBϕC31 attachment site. pJTU6722 (41) was used for amplifying the erythromycin resistance gene eryB flanked by the FLP recombination target (FRT) sequence in λ-Red-mediated PCR targeting. pET-28a (Novagen), pSUMO (42), and pSJ7 (43) were used for soluble protein expression. The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide function and name | Sequence (5′→3′)a |

|---|---|

| Gene deletions by PCR targeting | |

| Δrib-F | GCCACCGCACCGCCGTACGGGCCGGGCCGCGGCCGTCCGatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| Δrib-R | GCGGCCGACGATCTGCTGGTGGACGTCGGCTTCCACGCCgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| Δshi-F | GCGACGGGTGCGACGGGTGCGGAACATGGGAGCGGCCCTatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| Δshi-R | GTGTGGCTCCGCCACGCCGTCCGCTCCGCGCTGACCCGGgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlA-F | GACCCCCGAGACGAAGGAGCACCCCCGTGCGGCACTTCGAGCACTatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlA-R | CCCGCTGGTTGTCCGCCTCGACGACGAACCGGACCGTGCCCGTGTtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlB-F | GGAGATGGACGAGAACTCACTTGCCGATCCCTCTGTCGAAGCGTGatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlB-R | ACCTCGTCGCTCCCGCCCACGCACTCGGTGACGTCCTCCCCGGTGtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlC-F | ACGAGTACCTGGAGAGCCTCCGGGACGGCCGGGAAGTCAGGATCTatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlC-R | CGTACTTGTCCAGGTAGGGCCGGACCTCGGGGTTGGACCAGTCGAtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlD-F | GAGCCCCCGTCCTGCCGGACCAGGCCCAACTCAGGCACGTACTCGatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlD-R | GACAGCCGGTGTGCGGGCCGACGGCCCAGTCGGCGGCCTGCTCCAtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlE-F | GACTGCGCAGGCAGGGCGTCGAGGCGGTCGTCCACGAGCAGGCGCatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlE-R | GTGCCAGGAAGTGGGCGAGGACCACCGCGTCCTCCAGGGCCTGGTtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlF-F | ATGGCAAGGACCTACTCCTTCGAAGGCAACGTACCCGTCGTGCATatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlF-R | CTCGGTGGCGGCCTCCGCCGCGTGCAGACCGGTGAGACAGCGCTGtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlG-F | CACCTCCCGACTCGTCGTCGGCGACCGGTTCCGCGACTTCGCCGAatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlG-R | CAGCGGGCCGTGAAGTAGCGCTCCACCACCGCGACGAACATCTGAtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlH-F | ACCCGGAGTGGCGGTTCGCCTACCTGGGCCCGGAAGGAACCTTCAatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlH-R | CCAGGACTCTCAGTCCGGGCAGCCGCAGGCGCAGCAGGCCGACCGtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔtrlR-F | GACGTCGTCACCCCGCCCCCGTCGCGGCCGTGAGGACGTCCTCACatattccggggatccgtcgac |

| ΔtrlR-R | AGCAGCCGGGCGGCCAGGTGGGGAACGATGCCGTCGCGTATCTCGtgtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| ΔpaaABCDE-F | CAGATCGCCCAGCACGCGCACTCGGAGATCATCGGCATGCAGattccggggatccgtcgacc |

| ΔpaaABCDE-R | GCAGGTCCCGCAGACCCCGCCCTTGCAGGCGAAGGGCAGGTCtgtaggctggagctgcttc |

| Verification of gene deletion mutants | |

| ver-Δrib-F | ATGTCACCGCTGCGCACCGA |

| ver-Δrib-R | ACCTCCGGTACGGACCAGGA |

| ver-Δshi-F | TCACGAACAGCTTCACCCACT |

| ver-Δshi-R | GGCATCGAACTGTTCGACCTT |

| ver-ΔtrlA-F | GACGACCGGTCCGGAGATCG |

| ver-ΔtrlA-R | CGGGTCGCCGAGTGGTTCAG |

| ver-ΔtrlB-F | GAAGGCCAGGTCCATCGACTG |

| ver-ΔtrlB-R | CTAGTACCCGGGTAGTAGATC |

| ver-ΔtrlC-F | CACCGGCTCGAAAGGTGATC |

| ver-ΔtrlC-R | GTAGTTCATCTCGTACAGCTC |

| ver-ΔtrlD-F | GAGTACGACGAGCACGGCTG |

| ver-ΔtrlD-R | CCTGTTCGCTGCCGAAGGC |

| ver-ΔtrlE-F | CCTTCACCGAAGTCGCACC |

| ver-ΔtrlE-R | CGACGCAGACGCTCGTAGG |

| ver-ΔtrlF-F | GATCCACGGGCACGACATC |

| ver-ΔtrlF-R | CGTCCTGACGGTCTTGTCC |

| ver-ΔtrlG-F | CACCGGACGTCACGTTCAGG |

| ver-ΔtrlG-R | CTCCGACTCGTCCACCGTCAG |

| ver-ΔtrlH-F | GTACGACGGTGGAGGTGGAG |

| ver-ΔtrlH-R | CGATGAGCAGGTGGTCCAGG |

| ver-ΔtrlR-F | GAGATCCAGCGGATCCGTAC |

| ver-ΔtrlR-R | GTCGTTCAGACGCCGCACC |

| ver-ΔpaaABCDE-F | GAGCACTTCGACGCGACGATC |

| ver-ΔpaaABCDE-R | GACTGGCAGGTCAGCACGTAG |

| paaABCDE-F | ATGACCACGACACACGCCGC |

| paaABCDE-R | CGCACCACCCAGATGCTCAC |

| Amplification of trl genes for heterologous expression in E. coli | |

| trlC-F | AAAGAATTCATGAGCAGCACCGTCAACC |

| trlC-R | AAAAAGCTTTCACCGTGCGGCCGGGCG |

| trlD-F | AAAGAATTCATGAGCAGCCACACCCCC |

| trlD-R | AAAAAGCTTTCACGGCGCCGGTGCGAC |

| trlE-F | AAAGAATTCATGGCGAGGAAACGCCCGTAC |

| trlE-R | AAAAAGCTTTCAGGCCGGTGACGTGGCCAC |

| trlB-F | AAAGAATTCGTGGAATCCCTGGAGATGGAC |

| trlB-R | AAAAAGCTTACTAGTTCAGCCGGGGGACGCCGCGTG |

| trlH-F | AAACATATGAGGACGCCGACACCGGAC |

| trlH-R | AAAAAGCTTACTAGTTCACCGTGGTGACCGCCCC |

Lowercase letters in sequences represent sequences that match with two boundaries of the erythromycin resistance gene cassette from pJTU6722.

Culture conditions.

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium was used for E. coli growth. MS medium (44), containing, per liter, 20 g soybean flour, 20 g mannitol, and 20 g agar (pH 7.2 to 7.4) was used for Streptomyces growth, sporulation, and conjugation. R3 medium (45), containing, per liter, 10 g glucose, 5 g yeast extract, 0.1 g Casamino Acids, 3 g l-proline, 10 g MgCl2·6H2O, 4 g CaCl2·2H2O, 0.25 g K2SO4, 0.05 g KH2PO4, 5.6 g 2-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)-methylamino]-ethanesulfonic acid (TES), and 2 ml trace element solution (pH 7.2), was used for Streptomyces fermentation. The trace element solution was composed of ZnCl2 (40 mg), FeCl3·6H2O (200 mg), CuCl2·2H2O (10 mg), MnCl2·4H2O (10 mg), Na2B4O7·10H2O (10 mg), and (NH4)2Mo7O24·4H2O (10 mg) dissolved in 1 liter of double-distilled water (ddH2O). TSBY medium (44), containing, per liter, 30 g tryptone soy broth (TSB; Oxoid), 103 g sucrose, and 5 g yeast extract, was used to inoculate Streptomyces mycelium for genomic DNA extraction and seeding.

Materials and chemical reagents.

β-Thujaplicin (hinokitiol) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI). Antibiotics used in this study were purchased from Amresco; restriction enzymes were purchased from Fermentas (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the cosmid library production kit was purchased from Epicentre (catalog no. CCFOS110). Oligonucleotides were synthesized, and DNA sequencing was performed, by Jie Li Biology Co. Ltd. Taq DNA polymerase and Pfu DNA polymerase were purchased from Vazyme Biotech and Yeasen Biotech, respectively. Gel extraction and plasmid isolation kits were purchased from Omega Bio-tek.

Cosmid library construction and screening.

The cosmid library of S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 was constructed as described previously (34). High-molecular-weight genomic DNA (∼200 kb) of S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 was partially digested with Sau3AI and was then recovered for ligation with HpaI- and BamHI-digested pJTU2554 (40). MaxPlax lambda packaging extracts were used to package the ligation mixture and to transfect E. coli XL1-Blue MR/pUZ8002 competent cells (34), resulting in a genomic library with approximately 2,000 clones that were stored in 20 96-well plates at −80°C. The identical procedure was used to construct the cosmid genomic library of S. coelicolor M145, using SuperCos 1 as the vector.

A bioactivity-guided high-throughput library expression approach was used to identify the biosynthetic gene cluster for compound 1 as described previously (18). The S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 cosmid genomic library was inoculated into 96-well plates (130 μl/well) at 37°C and 220 rpm for 4 to 6 h until growth reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4 to 0.6. The E. coli cultures were then transferred to SFM plates (44) (supplemented with 20 mM MgSO4) precoated with heat-activated S. lividans SBT5 spores (a 48-pin replicator was used to transfer the cosmids into S. lividans SBT5). S. lividans SBT5/cosmid exconjugants were selected by flooding with apramycin (50 mg/liter) and trimethoprim (50 mg/liter), resulting in an expression library. The expression library was propagated in R3 medium at 28°C to 30°C for 4 to 6 days, followed by overlaying with B. subtilis and then culturing at 37°C for 16 to 24 h. Exconjugant 11A11, which showed antibacterial activity, was selected for further study.

Heterologous expression and large-DNA-fragment deletion.

The 11A11 cosmid (pCXF1) identified was transferred into S. coelicolor M1152 using E. coli-Streptomyces interspecies triparental mating, as described previously, for heterologous expression (44). S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF1 was selected and was then propagated in R3 medium for the production of compound 1. Meanwhile, pCXF1 was also isolated and sequenced at the China National Human Genome Centre at Shanghai, resulting in a 39-kb DNA sequence predicted to bear two clusters of genes responsible for riboflavin biosynthesis and shikimate metabolism, respectively.

λ-Red-mediated PCR targeting technology was used to construct Δorf7-to-orf25 (Δrib) and Δorf25-to-orf34 (Δshi) gene deletion mutants (36). PCR-targeting primers Δrib-F/Δrib-R (Δrib-F/R) and Δshi-F/R were used to amplify an erythromycin resistance gene cassette (eryB) from pJTU6722 (41) flanked by FLP recognition sites. The PCR products of the erythromycin resistance gene cassette were purified and were used to transform E. coli BW25113/pIJ790/pCXF1 competent cells by electroporation so as to replace orf7 to orf25 or orf25 to orf34 in pCXF1. The gene replacement constructs were then introduced into E. coli BT340, which was cultured at 42°C to remove the eryB cassette by FLP-mediated excision with an 81-bp scar remaining, resulting in constructs pCXF2 and pCXF3. The gene deletion constructs were confirmed by PCR analysis with primers ver-Δrib-F/R and ver-Δshi-F/R and by DNA sequencing. Finally, pCXF2 and pCXF3 were introduced into S. coelicolor M1152 individually by E. coli-Streptomyces triparental mating to integrate them into the ϕC31 attB site on the chromosome, yielding the corresponding gene deletion mutants S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF2 and S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF3.

Disruption of genes of the trl BGC in pCXF1.

Single-gene-disruption mutants of the trl BGC in pCXF1 were constructed by λ-Red-mediated PCR targeting technology as described above. The identical procedure, using PCR-targeting primers ΔtrlA-F/R to ΔtrlR-F/R, was applied to delete genes trlA through trlR from pCXF1 individually, resulting in constructs pCXF4 to pCXF12. PCR analysis using primers ver-ΔtrlA-F/R to ver-ΔtrlR-F/R was used to confirm the single-gene-disruption constructs. pCXF4 through pCXF12 were introduced into S. coelicolor M1152 as described above, resulting in the single-gene-disruption mutants S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF4 through S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF12.

Construction of the S. coelicolor M1152P mutant strain.

Primers ΔpaaABCDE-F/R were used to probe pCXF13 from the cosmid genomic library of S. coelicolor M145 using cosmid DNA as the template. The paaABCDE genes on pCXF13 were deleted by λ-Red-mediated PCR targeting technology as described above, using ΔpaaABCDE-F/R targeting primers. The paaABCDE region on pCXF13 was then replaced by the eryB resistance cassette, resulting in the pCXF14 construct. pCXF14 was then transferred into S. coelicolor M1152 by E. coli-Streptomyces triparental mating, and the DNA region encompassing paaABCDE on the chromosome was replaced by homologous double-crossover recombination, resulting in the S. coelicolor M1152 paaABCDE deletion strain S. coelicolor M1152P.

Metabolic analysis.

Streptomyces strains were cultured on SFM medium at 28 to 30°C for 4 to 6 days for sporulation. Then the Streptomyces spores were collected and were cultured on R3 agar petri dishes at 28 to 30°C for 4 to 6 days for metabolite production. R3 agar ferments were extracted three times with equal volumes of ethyl acetate (supplemented with 0.5% acetic acid), followed by concentration to dryness on a Buchi R-210 rotary evaporator at 35°C. The ethyl acetate extracts were first dissolved in methanol and then injected into an Agilent 1260 HPLC system for metabolic analysis on an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 column (particle size, 5 μm; inside diameter, 4.6 mm; length, 250 mm) using H2O containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (solvent A) and 100% acetonitrile (ACN) (solvent B) as the mobile phase. The column was equilibrated with 95% solvent A and 5% solvent B. For HPLC elution, the following procedure was used: from 0 to 15 min, 5% to 40% B; from 15 to 25 min, 40% to 100% B; from 25 to 30 min, 100% B; from 31 to 38 min, 5% B. Elution was carried out at a rate of 0.6 ml/min at room temperature. The crude extracts were also injected into an HPLC-mass selective detector (MSD) trap mass spectrometer for recording the mass (range, m/z 50 to 500) using the same column and elution gradient with the electrospray ionization (ESI) source operated in positive mode. Agilent quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) G6530 mass spectrometry was used for recording the high-resolution mass of each compound, operating in ESI positive mode. The pure compounds were dissolved in methanol-d4 or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6 for recording NMR signals on the Avance III 600-MHz NMR spectrometer. X-ray crystallography data were collected on a single crystal X-ray diffractometer (Bruker Smart Apex) at the State Key Laboratory of Organometallic Chemistry in the Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry.

Compound isolation. (i) Compound 1.

A 3-liter R3 agar ferment of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF1 was extracted three times with ethyl acetate (supplemented with 0.5% acetic acid) and was then concentrated under reduced evaporation at 35°C. The crude extract was then loaded onto a macroporous absorbent CHP20P resin column (diameter, 3.5 cm; length, 30 cm) and was eluted with an H2O–CH3OH gradient. The fractions were stored overnight at ambient temperature for crystallization, and brown crystals of compound 1 were obtained for subsequent HRMS and X-ray crystallography. The other compounds were obtained by identical procedures, with the exception of the details provided below.

(ii) Compound 10.

A 3-liter R3 agar ferment of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF7 (i.e., the ΔtrlD mutant) was used as the source. Brown crystals of compound 10 were obtained as described above and were used for HRMS, X-ray crystallography, and NMR analyses. NMR data are summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

(iii) Compounds 8 and 9.

A 10-liter R3 agar ferment of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF6 (i.e., the ΔtrlC mutant) was used as the source. Fractions containing compound 8 were collected for crystallization and were stored at ambient temperature overnight. As with compounds 1 and 10, brown crystals were obtained for compound 8 for further HRMS and X-ray crystallography analyses. The fractions containing compound 9 were collected and were then applied to a YMC C18 reversed-phase column (diameter, 2 cm; length, 20 cm) and were eluted with an H2O–CH3OH gradient (H2O/CH3OH ratios, 9:1, 17:3, 4:1, 7:3, 3:2, and 1:1). The fractions were monitored by HPLC using the method described under “Metabolic analysis” above. A pure sample of compound 9 (5 mg; elution at 20% methanol [MeOH]) was obtained for HRMS and NMR analyses.

(iv) Compounds 11 and 12.

A 5-liter R3 agar ferment of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF8 (i.e., the ΔtrlE mutant) was used as the source. HPLC fractions containing compound 11 or 12 were collected separately, concentrated to dryness under reduced evaporation at 35°C, and then applied to a YMC C18 reversed-phase column (diameter, 2 cm; length, 20 cm) and eluted with an H2O–CH3OH gradient (H2O/CH3OH ratios, 19:1, 9:1, 4:1, 7:3, 3:2, 1:1, 2:3, 3:7, 1:4, and 1:9). The fractions were monitored by HPLC using the method described under “Metabolic analysis” above. Pure samples of compound 11 (5 mg; elution at 10% MeOH) and compound 12 (5 mg; elution at 60% MeOH) were collected for structural elucidation. Compound 11 was characterized by comparison to a pure standard and HRMS, whereas compound 12 was characterized by NMR analysis.

(v) Compound 13.

A 5-liter R3 agar ferment of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF9 (i.e., the ΔtrlF mutant) was used as the source. HPLC fractions containing compound 13 were collected, concentrated to dryness for subsequent fractionation on a YMC C18 reversed-phase column (diameter, 2 cm; length, 20 cm), and eluted with an H2O–CH3OH gradient (H2O/CH3OH ratios, 7:3, 3:2, 1:1, 2:3, 3:7, 1:4, and 1:9). The fractions were monitored by HPLC using the method described under “Metabolic analysis” above. A pure sample of compound 13 (5 mg; elution at 80% MeOH) was obtained for HRMS and NMR analyses.

(vi) Compounds 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Compounds 3, 4, 5, and 6 were observed in the HPLC of R3 crude extracts of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF10 (i.e., the ΔtrlG mutant), S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF11 (i.e., the ΔtrlH mutant), and S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF12 (i.e., the ΔtrlR mutant). Of these, S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF10 was selected to obtain compounds 3, 4, 5, and 6 for structural elucidation. A 5-liter R3 agar ferment of S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF10 was extracted, concentrated, and fractionated using the procedure described above for S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF1. The fractions were monitored by HPLC, and fractions containing compounds 3, 4, 5, and 6 were collected separately, concentrated to dryness for subsequent fractionation on a YMC C18 reversed-phase column (diameter, 2 cm; length, 20 cm), and eluted with an H2O–CH3OH gradient (H2O/CH3OH ratios, 9:1, 4:1, 7:3, 3:2, 1:1, 2:3, 3:7, 1:4, and 1:9). The fractions were monitored by HPLC using the method described under “Metabolic analysis” above. Pure samples of compounds 3 (5 mg; elution at 60% MeOH), 4 (5 mg; elution at 40% MeOH), 5 (5 mg; elution at 40% MeOH), and 6 (5 mg; elution at 30% MeOH) were obtained. The fractions were stored overnight at ambient temperature for crystallization. White crystals of compound 3 were obtained.

Feeding of the S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF5 strain with compound 7.

S. coelicolor strain M1152/pCXF5 (i.e., the ΔtrlB mutant), which does not produce compound 1, was cultured on R3 agar petri dishes at 28 to 30°C for 2 days. A 200-μl volume of compound 7 dissolved in DMSO (2 mg/ml), was added, followed by 2 days of fermentation. Then 500 μl of compound 7 dissolved in DMSO (2 mg/ml) was added again, followed by a further 2 days of fermentation. R3 agar ferments were extracted three times with equal volumes of ethyl acetate (supplemented with 0.5% acetic acid), concentrated, and dissolved in methanol for HPLC analysis.

Feeding of the S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF10 strain with compounds 11, 8, and 10.

S. coelicolor strain M1152/pCXF10 (i.e., the ΔtrlG mutant), which does not produce compound 1, was inoculated into 30 ml TSBY seed medium and was incubated for 48 h with shaking at 220 rpm at 28 to 30°C. Then a 3-ml seed culture was inoculated into 30 ml R3 medium (10% seeding) in 250-ml baffled flasks. After 48 h of incubation at 28 to 30°C with shaking at 220 rpm, compounds 10 (3 mg), 8 (3 mg), and 11 (3 mg), dissolved in MeOH (300 μl), were added, followed by a further 4 days of fermentation. The R3 liquid ferments were then extracted with ethyl acetate (supplemented with 0.5% acetic acid), concentrated, and dissolved in methanol for HPLC analysis.

Cell-free experiments with S. coelicolor strain M1152/pCXF10 and compounds 11 and 13.

S. coelicolor M1152/pCXF10 was inoculated in 30 ml TSBY seed medium for 48 h with shaking at 220 rpm at 28 to 30°C. Then a 3-ml seed culture was transferred into 30 ml R3 medium (10% seeding) in a 250-ml baffled flask. After a 4-day incubation at 28 to 30°C with shaking at 220 rpm, the mycelium was collected by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and was washed three times with 50 mM Tris-Cl buffer (pH 7.5). The washed mycelium was resuspended with 5 ml of 50 mM Tris-Cl buffer (pH 7.5), incubated with lysozyme (2 mg/ml) for 2 h at 30°C, and subsequently lysed by ultrasonication (Soniprep 150; Sanyo) in an ice bath. The lysed mycelium mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min (4°C) to remove the cell debris, and the supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube ready for use. Compounds 11 (100 μg) and 13 (100 μg), dissolved in 50 μl DMSO, were then added to the 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and were incubated in a 30°C water bath for 2 h. Then ethyl acetate (supplemented with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) was added to stop the reaction, and the reaction product was extracted three times for HPLC analysis.

Cell-free experiments with E. coli BL21(DE3) strains.

The trlC and trlD genes were cloned into the pSJ7 and pSUMO vectors individually using primers trlC-F/R and trlD-F/R, respectively, resulting in the pCXF17 and pCXF18 constructs. pCXF17 and pCXF18 were transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3) to obtain the TrlC and TrlD expression strains E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF17 and E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF18, respectively. trlE was cloned into pET-28a using primers trlE-F/R, resulting in the pCXF19 construct, which was then transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) to obtain the TrlE expression strain E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF19.

A single colony of E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF17 was inoculated into 5 ml LB broth (with 50 mg/liter ampicillin) at 37°C, with shaking at 220 rpm overnight. A 1-ml E. coli culture was then transferred to 100 ml fresh LB broth (with 50 mg/liter ampicillin) and was incubated at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm for 2 to 3 h, to an OD600 of 0.4 to 0.6. IPTG was then added to a final concentration of 0.4 mM, and the culture was incubated at 16°C with shaking at 220 rpm for 16 to 20 h for protein expression. A 50-ml culture of E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF17 was pipetted into a 50-ml centrifuge tube, collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and washed three times with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). The E. coli cells were resuspended with 1 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and were subsequently lysed by ultrasonication (Soniprep 150; Sanyo) in an ice bath. The lysed cells were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min (4°C) to remove the cell debris, and the supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube ready for use. An identical procedure was used to prepare an E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF18 cell extract. Compound 8 (100 μg) was dissolved in 50 μl DMSO, added to the cell-free mixtures of E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF17 and E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF18, and incubated at 30°C for 2 h. The cell-free reaction mixture was then extracted with ethyl acetate (supplemented with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) for subsequent HPLC analysis.

E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF19, expressing TrlE, was cultured and lysed like E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF17 for the cell-free experiment. Compound 1 (100 μg), dissolved in 50 μl DMSO, was then added to the supernatant of the E. coli BL21(DE3)/pCXF19 cell lysate and was incubated at 30°C for 2 h. The cell-free reaction mixture was then extracted with ethyl acetate (supplemented with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) for subsequent HPLC analysis as described.

Sequence analysis.

The 39-kb DNA sequence of pCXF1 was submitted to antiSMASH (46) and 2ndfind (http://biosyn.nih.go.jp/2ndfind/) for identification of biosynthetic gene clusters for natural products. A BLASTP search (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) against the GenBank nonredundant and UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot databases was used to annotate the proteins encoded on pCXF1. The 3,7-dihydroxytropolone biosynthetic gene cluster cloned from S. luteogriseus Slg41 is identical to the S. cyaneofuscatus Soc7 trl BGC.

Accession number(s).

Newly determined sequence data were deposited in the GenBank database under accession number MF955860.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Songwang Hou, Tianshen Tao, Hongyu Ou, and Jianhua Ju for gifts of bacterial strains. We thank Bona Dai and Jieli Wu for NMR data.

This work was supported by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology through a China-Australia Joint Grant (2016YFE0101000), by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31370134, 31770036, and 21661140002), and by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant 15JC1400401).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00349-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bentley R. 2008. A fresh look at natural tropolonoids. Nat Prod Rep 25:118–138. doi: 10.1039/B711474E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grillo AS, SantaMaria AM, Kafina MD, Cioffi AG, Huston NC, Han M, Seo YA, Yien YY, Nardone C, Menon AV, Fan J, Svoboda DC, Anderson JB, Hong JD, Nicolau BG, Subedi K, Gewirth AA, Wessling-Resnick M, Kim J, Paw BH, Burke MD. 2017. Restored iron transport by a small molecule promotes absorption and hemoglobinization in animals. Science 356:608–616. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metcalfe H, Field R, Froud S. 1994. The use of 2-hydroxy-2,4,6-cycloheptarin-1-one (tropolone) as a replacement for transferrin, p 88–90. In Spier RE, Griffiths JB, Berthold W, (ed), Animal cell technology: products of today, prospects for tomorrow. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azegami K, Nishiyama K, Watanabe Y, Suzuki T, Yoshida M, Nose K, Toda S. 1985. Tropolone as a root growth-inhibitor produced by a plant pathogenic Pseudomonas sp. causing seedling blight of rice. Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn 51:315–317. doi: 10.3186/jjphytopath.51.315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugawara K, Ohbayashi M, Shimizu K, Hatori M, Kamei H, Konishi M, Oki T, Kawaguchi H. 1988. BMY-28438 (3,7-dihydroxytropolone), a new antitumor antibiotic active against B16 melanoma. I. Production, isolation, structure and biological activity. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 41:862–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Didierjean J, Isel C, Querre F, Mouscadet JF, Aubertin AM, Valnot JY, Piettre SR, Marquet R. 2005. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase, RNase H, and integrase activities by hydroxytropolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:4884–4894. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.4884-4894.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piettre SR, Ganzhorn A, Hoflack J, Islam K, Hornsperger JM. 1997. α-Hydroxytropolone: a new class of potent inhibitors of inositol monophosphatase and other bimetallic enzymes. J Am Chem Soc 119:3201–3204. doi: 10.1021/ja9634278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donlin MJ, Zunica A, Lipnicky A, Garimallaprabhakaran AK, Berkowitz AJ, Grigoryan A, Meyers MJ, Tavis JE, Murelli RP. 2017. Troponoids can inhibit growth of the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02574-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02574-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Falcone ER, Holstein SA, Anderson AC, Wright DL, Wiemer AJ. 2016. Novel alpha-substituted tropolones promote potent and selective caspase-dependent leukemia cell apoptosis. Pharmacol Res 113:438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meck C, D'Erasmo MP, Hirsch DR, Murelli RP. 2014. The biology and synthesis of alpha-hydroxytropolones. MedChemComm 5:842–852. doi: 10.1039/C4MD00055B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox RJ, Al-Fahad A. 2013. Chemical mechanisms involved during the biosynthesis of tropolones. Curr Opin Chem Biol 17:532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davison J, al Fahad A, Cai M, Song Z, Yehia SY, Lazarus CM, Bailey AM, Simpson TJ, Cox RJ. 2012. Genetic, molecular, and biochemical basis of fungal tropolone biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:7642–7647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201469109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan Y, Yang J, Yu Z, Yu M, Ma YT, Wang L, Su C, Luo J, Horsman GP, Huang SX. 2016. Non-enzymatic pyridine ring formation in the biosynthesis of the rubrolone tropolone alkaloids. Nat Commun 7:13083. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teufel R, Gantert C, Voss M, Eisenreich W, Haehnel W, Fuchs G. 2011. Studies on the mechanism of ring hydrolysis in phenylacetate degradation: a metabolic branching point. J Biol Chem 286:11021–11034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teufel R, Mascaraque V, Ismail W, Voss M, Perera J, Eisenreich W, Haehnel W, Fuchs G. 2010. Bacterial phenylalanine and phenylacetate catabolic pathway revealed. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:14390–14395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005399107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brock NL, Nikolay A, Dickschat JS. 2014. Biosynthesis of the antibiotic tropodithietic acid by the marine bacterium Phaeobacter inhibens. Chem Commun (Camb) 50:5487–5489. doi: 10.1039/c4cc01924e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang R, Gallant É, Seyedsayamdost MR. 2016. Investigation of the genetics and biochemistry of roseobacticide production in the Roseobacter clade bacterium Phaeobacter inhibens. mBio 7:e02118-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02118-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu M, Wang Y, Zhao Z, Gao G, Huang SX, Kang Q, He X, Lin S, Pang X, Deng Z, Tao M. 2016. Functional genome mining for metabolites encoded by large gene clusters through heterologous expression of a whole-genome bacterial artificial chromosome library in Streptomyces spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:5795–5805. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01383-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dosselaere F, Vanderleyden J. 2001. A metabolic node in action: chorismate-utilizing enzymes in microorganisms. Crit Rev Microbiol 27:75–131. doi: 10.1080/20014091096710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xun L, Sandvik ER. 2000. Characterization of 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-hydroxylase (HpaB) of Escherichia coli as a reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide-utilizing monooxygenase. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:481–486. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.2.481-486.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiménez JI, Canales A, Jiménez-Barbero J, Ginalski K, Rychlewski L, García JL, Díaz E. 2008. Deciphering the genetic determinants for aerobic nicotinic acid degradation: the nic cluster from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:11329–11334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802273105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eichler K, Bourgis F, Buchet A, Kleber HP, Mandrand-Berthelot MA. 1994. Molecular characterization of the cai operon necessary for carnitine metabolism in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 13:775–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrández A, Miñambres B, García B, Olivera ER, Luengo JM, García JL, Díaz E. 1998. Catabolism of phenylacetic acid in Escherichia coli. Characterization of a new aerobic hybrid pathway. J Biol Chem 273:25974–25986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blakley ER. 1977. The catabolism of l-tyrosine by an Arthrobacter sp. Can J Microbiol 23:1128–1139. doi: 10.1139/m77-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahanta N, Fedoseyenko D, Dairi T, Begley TP. 2013. Menaquinone biosynthesis: formation of aminofutalosine requires a unique radical SAM enzyme. J Am Chem Soc 135:15318–15321. doi: 10.1021/ja408594p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Lanen SG, Lin S, Shen B. 2008. Biosynthesis of the enediyne antitumor antibiotic C-1027 involves a new branching point in chorismate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:494–499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708750105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dastan A, Balci M. 2006. Chemistry of dioxine-annelated cycloheptatriene endoperoxides and their conversion into tropolone derivatives: an unusual non-benzenoid singlet oxygen source. Tetrahedron 62:4003–4010. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doering WVE, Detert FL. 1951. Cycloheptatrienylium oxide. J Am Chem Soc 73:876–877. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grundmann C, Ottmann G. 1953. Preparation and structure of the isomeric cycloheptatriene carboxylic acids. Liebigs Ann Chem 582:15. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Citron CA, Barra L, Wink J, Dickschat JS. 2015. Volatiles from nineteen recently genome sequenced actinomycetes. Org Biomol Chem 13:2673–2683. doi: 10.1039/C4OB02609H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore BS, Walker K, Tornus I, Handa S, Poralla K, Floss HG. 1997. Biosynthesis studies of ω-cycloheptyl fatty acids in Alicyclobacillus cycloheptanicus. Formation of cycloheptanecarboxylic acid from phenylacetic acid. J Org Chem 62:2173–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rost R, Haas S, Hammer E, Herrmann H, Burchhardt G. 2002. Molecular analysis of aerobic phenylacetate degradation in Azoarcus evansii. Mol Genet Genomics 267:656–663. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0699-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thiel V, Brinkhoff T, Dickschat JS, Wickel S, Grunenberg J, Wagner-Döbler I, Simon M, Schulz S. 2010. Identification and biosynthesis of tropone derivatives and sulfur volatiles produced by bacteria of the marine Roseobacter clade. Org Biomol Chem 8:234–246. doi: 10.1039/B909133E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L, Wang Y, Guo H, Xu M, Deng Z, Tao M. 2012. High-throughput screening for Streptomyces antibiotic biosynthesis activators. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:4526–4528. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00348-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gust B, Challis GL, Fowler K, Kieser T, Chater KF. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:1541–1546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337542100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flett F, Mersinias V, Smith CP. 1997. High efficiency intergeneric conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli to methyl DNA-restricting streptomycetes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 155:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb13882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bai T, Yu Y, Xu Z, Tao M. 2014. Construction of Streptomyces lividans SBT5 as an efficient heterologous expression host. J Huazhong Agric Univ 33:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez-Escribano JP, Bibb MJ. 2011. Engineering Streptomyces coelicolor for heterologous expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters. Microb Biotechnol 4:207–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li L, Xu Z, Xu X, Wu J, Zhang Y, He X, Zabriskie TM, Deng Z. 2008. The mildiomycin biosynthesis: initial steps for sequential generation of 5-hydroxymethylcytidine 5′-monophosphate and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in Streptoverticillium rimofaciens ZJU5119. Chembiochem 9:1286–1294. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Z, Shi T, Xu M, Brock NL, Zhao YL, Wang Y, Deng Z, Pang X, Tao M. 2016. Hybrubins: bipyrrole tetramic acids obtained by crosstalk between a truncated undecylprodigiosin pathway and heterologous tetramic acid biosynthetic genes. Org Lett 18:572–575. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peroutka RJ III, Orcutt SJ, Strickler JE, Butt TR. 2011. SUMO fusion technology for enhanced protein expression and purification in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Methods Mol Biol 705:15–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-967-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou J, Liu CY, Back SH, Clark RL, Peisach D, Xu Z, Kaufman RJ. 2006. The crystal structure of human IRE1 luminal domain reveals a conserved dimerization interface required for activation of the unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:14343–14348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606480103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shima J, Hesketh A, Okamoto S, Kawamoto S, Ochi K. 1996. Induction of actinorhodin production by rpsL (encoding ribosomal protein S12) mutations that confer streptomycin resistance in Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J Bacteriol 178:7276–7284. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7276-7284.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, Lee SY, Fischbach MA, Muller R, Wohlleben W, Breitling R, Takano E, Medema MH. 2015. antiSMASH 3.0—a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.