Abstract

Background/objective

There is substantial interest in dietary approaches to reducing postprandial glucose (PPG) responses, but the quantitative contribution of PPG to longer-term glycemic control (reflected in glycated hemoglobin, HbA1c) in the general population is not known. This study quantified the associations of preprandial glucose exposure, PPG exposure, and glycemic variability with HbA1c and estimated the explained variance in HbA1c in individuals with and without type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Subjects/methods

Participants in the A1c-Derived Average Glucose (ADAG) study without T2D (n = 77) or with non-insulin-treated T2D and HbA1c<6.5% (T2DHbA1c < 6.5%, n = 63) or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5%, n = 34) were included in this analysis. Indices of preprandial glucose, PPG, and glycemic variability were calculated from continuous glucose monitoring during four periods over 12 weeks prior to HbA1c measurement. In linear regression models, we estimated the associations of the glycemic exposures with HbA1c and calculated the proportion of variance in HbA1c explained by glycemic and non-glycemic factors (age, sex, body mass index, and ethnicity).

Results

The factors in the analysis explained 35% of the variance in HbA1c in non-diabetic individuals, 49% in T2DHbA1c < 6.5%, and 78% in T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5%. In non-diabetic individuals PPG exposure was associated with HbA1c in confounder-adjusted analyses (P < 0.05). In the T2DHbA1c < 6.5% group, all glycemic measures were associated with HbA1c (P < 0.05); preprandial glucose and PPG accounted for 14 and 18%, respectively, of the explained variation. In T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5%, these glycemic exposures accounted for more than 50% of the variation in HbA1c and with equal relative contributions.

Conclusions

Among the glycemic exposures, PPG exposure was most strongly predictive of HbA1c in non-diabetic individuals, suggesting that interventions targeting lowering of the PPG response may be beneficial for long-term glycemic maintenance. In T2D, preprandial glucose and PPG exposure contributed equally to HbA1c.

Introduction

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reflects glycemic exposure in the previous 8–12 weeks1. The level of HbA1c is in addition to glycemia determined by the lifespan of erythrocytes, which is affected by nutritional deficiencies, for example, iron deficiency anemia and vitamin B12 deficiency2. In addition to nutritional deficiencies sex, genetic factors, and hematologic parameters are non-glycemic factors affecting HbA1c concentrations1.

High HbA1c concentrations are associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality in individuals with and without type 2 diabetes (T2D)3–6. Individuals without T2D spend a considerable amount of time during the day at glucose concentrations considered to be prediabetic (>7.8 mmol/L)7. Accordingly, lifestyle or pharmaceutical interventions targeting lowering of postprandial glucose (PPG) directly or via the underlying insulin sensitivity are relevant even in the non-diabetic population8. However, the exact contribution of normally experienced, daily PPG exposures and daytime glucose variability to variation in HbA1c in individuals with and without T2D is currently unknown, because few studies have captured these fluctuations over sustained periods under free-living conditions, for example, by use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM)8, 9.

In the current analysis, we aimed to compare the strength of the associations of real-life preprandial and PPG exposures as well as glycemic variability with HbA1c concentrations in non-diabetic individuals and in persons with non-insulin-treated T2D with different levels of glycemic control. Moreover, we aimed to estimate the variance in HbA1c concentrations explained by preprandial and PPG exposures, glycemic variability, and non-glycemic characteristics in these subgroups.

Materials/subjects and methods

Study population

The A1c-Derived Average Glucose (ADAG) study is a multicenter study including 11 centers in the United States, Europe, Africa, and Asia. From January 2006 to March 2008, 268 individuals with T1D, 159 with T2D, and 80 free of diabetes completed a 16-week period of intensive CGM and self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG). Individuals without diabetes had no family history of diabetes and a fasting plasma glucose concentration ≤5.4 mmol/L after an overnight fast. Persons with diabetes had to have stable glycemic control as evidenced by two HbA1c values within 1 percentage point (~11 mmol/mol) of each other in the 6 months before recruitment. Diabetes management was left to the participants and their usual health care providers. Individuals with T1D were not considered in this study because we did not want to include individuals on insulin treatment. We further excluded 60 persons with T2D who were treated with insulin and five because of missing BMI (two with diabetes and three without), leaving 77 individuals without diabetes (non-DM) and 97 participants with T2D for the present analysis. Participants with T2D were further subdivided into those meeting and exceeding the target HbA1c level for diabetes management of <6.5%/48 mmol/mol (respectively “T2DHbA1c<6.5%,” n = 63; and “T2DHbA1c≥6.5%,” n = 34).

The ADAG study was approved by the human studies committees for each of the participating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion in the study.

Data collection and study procedures

Characteristics

Clinical data collected at baseline included age, sex, height, weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, and treatment with insulin, lipid-lowering, or antihypertensive medication. Blood samples for HbA1c and plasma lipids were obtained at baseline and monthly for 3 months (i.e., four repeat measurements in total). Information on ethnicity was coded as being of white or non-white origin.

Continuous glucose monitoring

Measures of glycemia were performed using the blinded CGM system (Medtronic Minimed, Northridge, CA, USA), which measures glucose concentrations every 5 min. The measurements were performed for at least 2 days at baseline and then again for at least 2 days every 4 weeks during the next 12 weeks. At least one successful 24-h profile out of the 2–3 days of monitoring with no gaps >120 min and a mean absolute difference of <18% compared with the Hemocue calibration results was required to be included in the analysis. Measures from the first 2 h of CGM measurement were excluded, since this period is considered an unstable calibration period. During the CGM measurement periods, the participants performed daily 8-point SMBG profiles with a HemoCue meter (HemoCue Glucose 201 Plus, Hemocue, Ängelholm, Sweden). SMBG was performed right before and 90 min after breakfast, lunch, and dinner as well as at bedtime and at 3 a.m. The SMBG measurements were used for calibration purposes, and the time points of SMBG measurements were used for definition of preprandial and postprandial periods.

Laboratory analyses

Blood samples taken at the clinical examinations were frozen at −80 °C and were sent on dry ice by overnight shipment to a central laboratory. As the ADAG study was part of the standardization of HbA1c measurements, samples for determination of HbA1c were analyzed with four different DCCT-aligned assays, including a high-performance liquid chromatography assay (Tosoh G7; Tosoh Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan), two immunoassays (Roche A1C and Roche Tina-quant; Roche Diagnostics), and one affinity assay (Primus Ultra-2; Primus Diagnostics, Kansas City, MO, USA). The mean value of the four HbA1c measurements at the 12-week visit was used in the analysis. A detailed description of the study has been published previously10.

Calculations

HbA1c reflects the average glycemia over the preceding 8–12 weeks. Accordingly, the mean values of the different glycemic measures over the first three CGM measurement periods (0, 4, and 8 weeks) were used as explanatory variables and HbA1c measured at the last visit (12 weeks of follow-up) was used as outcome (Supplementary Figure S1). The calculations used to derive these are specified below.

Preprandial glycemic measures

A measure of pre-breakfast glycemia was obtained from the CGM measurements at 0, 4, and 8 weeks as the average glucose concentration from t = −15 min to t = 0 min pre-breakfast. An index of nocturnal glycemia was calculated as mean glucose concentrations from the CGM period from 2 a.m. to 4 a.m. from the same visits.

Postprandial glycemic measures

From the CGM data we estimated postprandial periods as the areas under the glucose curves (AUCs) from time of intake of breakfast, lunch, and dinner and until 2 h after the meal intake. These time points were derived from the SMBG data. The mean AUC of all larger meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) over all measurement days at 0, 4, and 8 weeks was calculated. In addition to the AUCs, we also calculated mean incremental AUCs as (AUC – (preprandial glucose concentration × 2 h)) over the same measurement periods. Additionally, incremental AUCs were averaged for each meal type (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) over the three visits and further averaged over meals to provide an overall mean estimate. Peak glucose was estimated as the single highest glucose concentration obtained during one of these CGM measurement periods (0, 4, or 8 weeks).

Glycemic variability

As a measure of glycemic variability the mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (MAGE) was calculated from CGM data. MAGE is the mean of the differences between consecutive peaks and nadirs, only including changes >1 SD of glycemic values and thereby only capturing major fluctuations11, 12. Additionally, the standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of the glycemic values were calculated from the CGM data. CV is the SD divided by the mean13. Also MAGE, SD, and CV were averaged over the three first visits (0, 4, and 8 weeks).

Statistical analyses

Linear regression analysis was used to estimate the associations of preprandial glycemia (pre-breakfast glucose and nocturnal glucose), postprandial glycemia (total AUC, incremental AUC, and peak glucose), as well as glycemic variability (MAGE, SD, and CV) with HbA1c. The analyses were stratified by the three groups (no diabetes, T2DHbA1c < 6.5%, and T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5%). Analyses were performed without adjustment and with adjustment for age, sex, BMI, and ethnicity. Prior to analysis, the eight measures of glycemia were standardized to allow direct comparisons of the strength of their association with HbA1c. The corresponding regression coefficients will thus reflect the difference in HbA1c per 1 population SD difference in the glycemic measures.

In unadjusted linear regression analysis, using the same three groups, we calculated the proportion of variance in HbA1c explained by the following categories of glycemic measures: preprandial glucose (nocturnal and pre-breakfast glucose), PPG (AUC glucose, incremental AUC glucose and peak glucose), glycemic variability (MAGE, SD, and CV), and non-glycemic factors (age, sex, BMI, and ethnicity). First, we modeled the association between HbA1c and each of the four categories of glucose measures in order to estimate their individual contributions to explaining the variance in HbA1c. Second, the combined contribution of the four categories of glucose measures was calculated in a multiple linear regression analysis including all glycemic measures. Because the four categories of glucose measures (preprandial glucose, PPG, glycemic variability, and non-glycemic factors) to some extent are correlated, the sum of their individual contributions will likely exceed the proportions of variance explained by including all four categories in the same model. We therefore used the latter result to scale the individual contributions in order for them to add up to the total variance explained in HbA1c by all the measures in combination. We also performed a sensitivity analysis, including only pre-breakfast glucose, AUC glucose, and SD as measures of preprandial and postprandial glycemia and glycemic variability, respectively.

Statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.2.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A two-sided P ≤ 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance in all analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the study participants at baseline stratified by diabetes status. Compared to those with T2D, the healthy population without diabetes was younger and leaner and had a more favorable cardiometabolic profile as well as a lower use of lipid-lowering and blood pressure-lowering medications. Within the T2D population, those with the lower HbA1c concentration were more likely to be men, and they were leaner and had lower systolic blood pressure than those with higher HbA1c concentrations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population by glycemic status

| No diabetes (n = 77) |

T2DHbA1c < 6.5% (n = 63) |

T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5% (n = 34) |

Overall P |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 41.1 (13.7) | 56.0 (10.0)a | 53.7 (8.8)a | <0.001 |

| Male sex (%) | 31.2 (21.1;42.7) | 57.1 (44.0;69.5)a | 32.4 (17.4;50.5)b | 0.004 |

| White ethnicity (%) | 68.8 (57.3;78.9) | 76.2 (63.8;86.0) | 50.0 (32.4;67.6)b | 0.034 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.3 (14.7) | 89.6 (24.4)a | 95.8 (25.5)a | <0.001 |

| Waist (cm) | 84.8 (13.1) | 101.3 (18.0)a | 110.7 (18.8)a,b | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 (4.9) | 31.3 (8.2)a | 35.2 (8.1)a,b | <0.001 |

| Current smokers (%) | 7.8 (2.9;16.2) | 6.3 (1.8;15.5) | 11.8 (3.3;27.5) | 0.660 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 118.7 (15.2) | 128.8 (15.4)a | 135.7 (13.8)a,b | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74.2 (9.8) | 77.5 (10.4)a | 80.8 (6.8)a | 0.003 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.7 (0.9) | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.2 (1.0) | 0.112 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.4)a | 1.1 (0.4)a | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.5 (1) | 2.2 (0.8) | 0.172 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.0 (0.7;1.6) | 1.7 (1.1;2.7)a | 1.7 (1.2;2.4)a | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive treatment (%) | 12.0 (5.6;21.6) | 54.0 (40.9;66.6)a | 52.9 (35.1;70.2)a | <0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering treatment (%) | 4.0 (0.8;11.2) | 52.4 (39.4;65.1)a | 44.1 (27.2;62.1)a | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.2 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.6)a | 7.5 (1.2)a,b | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 33.3 (2.8) | 43.4 (6.3)a | 58.1 (12.9)a,b | <0.001 |

| Preprandial glycemia | ||||

| Pre-breakfast glucose (mmol/L) | 5.8 (0.6) | 7.2 (1.8)a | 8.6 (2.8)a,b | <0.001 |

| Nocturnal glucose (mmol/L) | 5.7 (0.9) | 6.8 (1.2)a | 8.1 (2.6)a,b | <0.001 |

| Postprandial glycemia | ||||

| AUC glucose (h·mmol/L) | 12.1 (1.6) | 15.7 (3.3)a | 20.0 (5.2)a,b | <0.001 |

| iAUC glucose (h·mmol/L) | 0.5 (0.8) | 1.9 (1.7)a | 2.8 (2.5)a,b | <0.001 |

| iAUCbreakfast glucose (h·mmol/L) | 0.6 (1.2) | 2.5 (2.8)a | 4.0 (4.2)a,b | <0.001 |

| iAUClunch glucose (h·mmol/L) | 0.7 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.9)a | 2.5 (3.1)a | <0.001 |

| iAUCdinner glucose (h·mmol/L) | 0.3 (1.2) | 1.5 (2.5)a | 1.6 (2.5)a | <0.001 |

| Peak glucose (mmol/L) | 8.9 (2.1) | 12.0 (3.0)a | 16.3 (3.8)a,b | <0.001 |

| Glycemic variability | ||||

| MAGE (mmol/L) | 1.5 (1.1;1.9) | 2.8 (1.8;4.5)a | 4.6 (3.2;6.4)a,b | <0.001 |

| SD (mmol/L) | 0.8 (0.6;1.0) | 1.5 (1.0;2.0)a | 2.2 (1.6;2.6)a | <0.001 |

| CV (%) | 13.6 (10.8;16.3) | 19.8 (16.0;25.9)a | 23.6 (18.4;30.4)a | <0.001 |

Data are shown as means (SD), medians (interquartile range), or percentages (95% CI).

Pairwise differences are illustrated by letters: a P < 0.05 vs. no diabetes; b P < 0.05 vs. T2DHbA1c < 6.5%

Parameters with non-normally distributed values were log-transformed prior to the test.

AUC area under the curve for 2 h after meal intake, iAUC incremental area under the curve for 2 h after meal intake.

Relationships between glycemic measures and HbA1c concentrations

The median number of days with valid CGM measurements in the study population was 13 with a range from 3 to 19 days. Pairwise scatter diagrams of the interrelationships between the eight different glycemic measures by the three groups (no diabetes, T2DHbA1c < 6.5%, and T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5%) are shown in Supplementary Figures S2–S4. In all three groups, pre-breakfast glucose was highly correlated with AUC glucose (P < 0.001), but not with incremental AUC glucose (P ≥ 0.056).

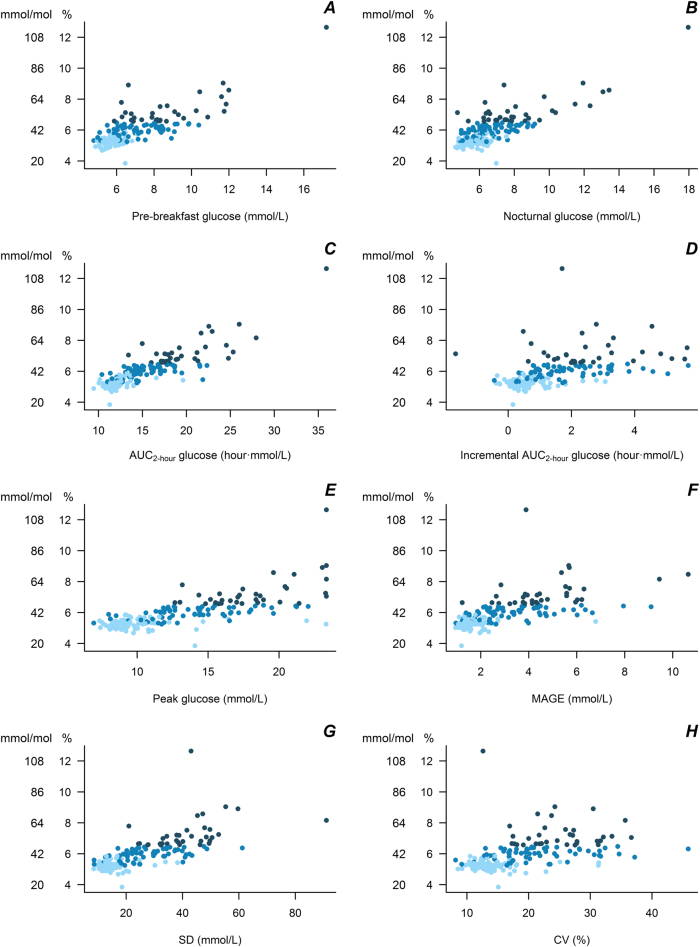

Scatter plots of HbA1c measurements vs. measurements of preprandial glucose (nocturnal and pre-breakfast glucose), PPG (AUC glucose, incremental AUC glucose, and peak glucose), and glycemic variability (MAGE, SD, and CV) are shown in Fig. 1. All associations were statistically significant (P < 0.001), but with largest variation at higher glycemic levels.

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot of HbA1c measurements vs. measurements of pre-breakfast glucose (a), nocturnal glucose (b), AUC glucose (c), incremental AUC glucose (d), peak glucose (e), MAGE (f), SD (g), and CV (h) obtained from continues glucose monitoring (P < 0.001 for all associations). Light blue: No diabetes; blue: T2DHbA1c < 6.5%; dark blue: T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5%

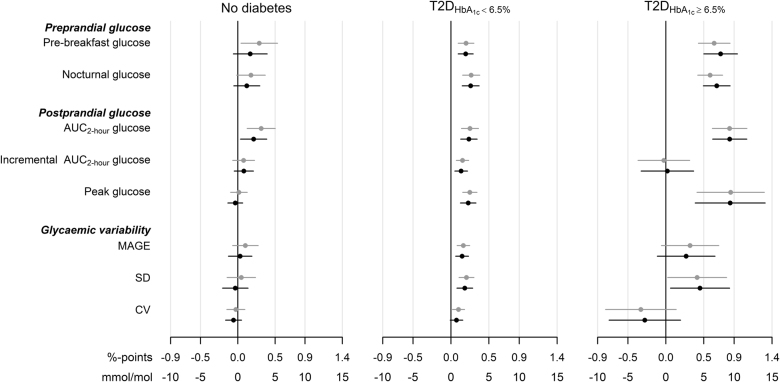

Unadjusted and adjusted associations of HbA1c with glycemic markers by the three groups are shown in Fig. 2. Total AUC glucose was more strongly associated with HbA1c than the other glycemic markers in all three groups, and this association was robust after adjustment for confounders (Fig. 2) and for pre-breakfast glucose concentrations (P ≤ 0.032 for all groups).

Fig. 2.

Mean (95% CI) difference in HbA1c by an SD difference in glycemia for participants without diabetes, T2DHbA1c < 6.5%: non-insulin-treated diabetes and HbA1c < 6.5%/48 mmol/mol or T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5%: non-insulin-treated diabetes and HbA1c ≥ 6.5%/48 mmol/mol. Estimated differences are unadjusted (gray) or adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and ethnicity (black)

Among individuals without diabetes, pre-breakfast glucose and AUC glucose were significantly associated with HbA1c before adjustment, but in the analyses adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and ethnicity, only the association of AUC glucose with HbA1c remained significant (~2 mmol/mol increase in HbA1c per SD increase in AUC glucose; Fig. 2). In the T2DHbA1c < 6.5% group, all the glycemic variables were significantly associated with HbA1c and with largest associations for nocturnal glucose and AUC glucose—also after confounder adjustment except for CV (~3 mmol/mol increase in HbA1c per SD increase in the glycemic variables; Fig. 2). For the T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5% group, the associations between glycemic variables and HbA1c were overall stronger than in the other groups. For this group both pre-breakfast glucose and nocturnal glucose as well as AUC glucose, peak glucose, and SD of glucose were significantly associated with HbA1c both before and after confounder adjustment and with a change in HbA1c of up to 9 mmol/mol per SD increase in glycemia (Fig. 2). The incremental AUC was not associated with HbA1c in the T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5% group when considering all meals or when studying breakfast, lunch, and dinner, separately (Supplementary Figure S5).

Relative contributions of glycemic and non-glycemic factors to variation in HbA1c

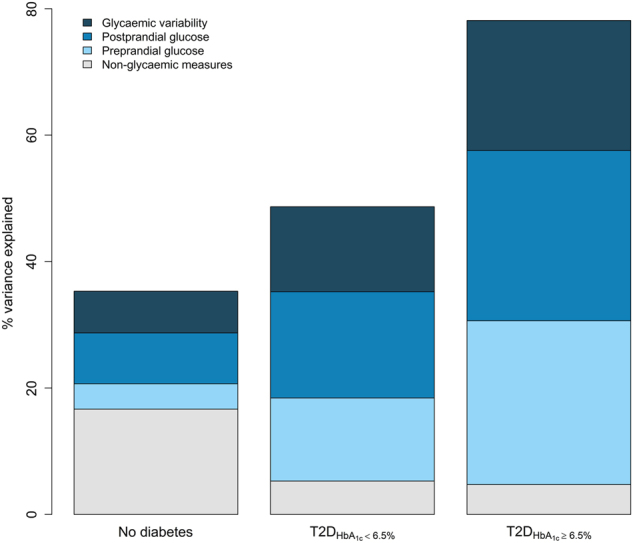

Figure 3 illustrates the proportion of variance in HbA1c explained by preprandial glucose, PPG, glycemic variability, and non-glycemic factors in the three groups.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of variance explained in HbA1c by non-glycemic factors (age, sex, BMI, ethnicity), preprandial glucose (pre-breakfast and nocturnal glucose), postprandial glucose (total and incremental area under the curve as well as peak glucose), and glycemic variability (MAGE, SD, and CV) by diabetes status and HbA1c levels.

In the non-diabetic population, 35% of the variance in HbA1c was explained by the included variables, and here the included non-glycemic factors accounted for half of the variance explained. Preprandial glucose explained 4%, PPG 8%, and glycemic variability 7% of the variance in HbA1c.

Among those with T2DHbA1c < 6.5%, 49% of the variance in HbA1c was explained by the variables included in the model. Here the contribution of non-glycemic factors was small (5% of the variance explained), whereas preprandial glucose, PPG, and glycemic variability explained 13, 17, and 13%, respectively, of the variance in HbA1c.

For the T2DHbA1c≥6.5% group, 78% of the variance in HbA1c could be explained by the non-glycemic and glycemic factors included in the model. Preprandial and postprandial glycemia explained similarly large proportions (about 27% each) of the variance in HbA1c and glycemic variability explained 20%. Again, non-glycemic factors only explained 5% of the variance.

Inclusion of only pre-breakfast glucose, total AUC and SD as measures of preprandial glycemic, postprandial glycemia, and glycemic variability, respectively, reduced the contributions from preprandial glucose and PPG to HbA1c, especially in the T2DHbA1c < 6.5% group. The contribution from glycemic variability was also reduced, especially in the non-diabetic population and in the T2DHbA1c ≥ 6.5% group (Supplementary Figure S6).

Discussion

In this analysis based on repeated CGM measurements under free-living conditions, we found that PPG exposure contributed more than preprandial glucose or glucose variability exposure to variation in HbA1c in non-diabetic individuals. In individuals with non-insulin-treated T2D, preprandial glucose and PPG contributed equally and slightly more than glycemic variability to variation in HbA1c. We also showed that glycemic factors as well as age, sex, BMI, and ethnicity accounted for only one-third of the explained variance in HbA1c among individuals without diabetes, whereas these same factors accounted for nearly 80% of the explained variance in HbA1c among non-insulin-treated T2D patients with HbA1c ≥ 6.5%. Finally, we demonstrated that the contribution of non-glycemic factors to the explained variance in HbA1c was 3–4 times higher in the non-diabetic population than in those with T2D.

The frequent CGM measurement periods during free-living conditions in combination with HbA1c measured by high-quality techniques after 3 months of glucose exposure made it possible to assess the contributions of real-life glycemic exposures to the variation in HbA1c in a large heterogeneous group of individuals with and without T2D. HbA1c is a measure of the average blood glucose concentration over the last 8–12 weeks and is determined by glycemic as well as genetic, hematologic, and illness-related factors1. Changes in the lifespan of the erythrocytes can therefore affect HbA1c concentrations, such that a higher mean age of erythrocytes will lead to higher HbA1c concentrations1. The average survival of erythrocytes is slightly longer in men (117 days) than in women (106 days), so also sex can confound HbA1c concentrations in a given population. Accordingly, we adjusted for age and sex in our analyses. In the ADAG study, individuals with anemia or with severe liver or renal disease were excluded from participation in order to avoid effects of iron deficiency anemia on HbA1c concentrations. Factors, unrelated to age and sex, have been examined in twin studies. In non-diabetic, healthy, female twins with similar glucose tolerance, 62% of the between-person variation in HbA1c was attributable to genetic factors, with the remainder reflecting age and environmental factors14. The relatively high contribution of non-glycemic factors to HbA1c in non-diabetic individuals may explain the relatively poor overlap among fasting glucose, glucose tolerance, and HbA1c in this population15, 16. This also suggests that markers other than HbA1c might better capture the relatively subtle differences in glycemia among non-diabetic individuals17.

A number of observational studies have documented associations of lower dietary glycemic index and glycemic load with reduced risk of developing T2D and coronary heart disease18, 19. Likewise, a large trial in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance showed that administration of acarbose (a PPG lowering drug) with meals three times daily for 5 years reduced the incidence of diabetes by 18% compared to placebo20. Together these findings support the notion that modification of PPG by either diet or medication may have beneficial consequences for cardiometabolic health, including markers of glycemic control and thus risk of diabetes. However, the contributions to HbA1c of “usual,” real-time PPG exposures has until now been unclear, because most previous studies have assessed outcomes in relation to either glycemic control in individuals or the glycemic potential of foods. Former studies consider relationships with individual variation in responses to standardized meal tests, and not under free-living conditions8, 9. This is an important aspect because glucose concentrations after a standard meal test mainly reflect the health status of an individual (i.e., glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, and β-cell capacity) but does not directly inform about the actual, lifestyle-related glucose exposures in the previous weeks to months. Alternatively, studies on the glycemic potential of foods or diets (e.g., glycemic index or glycemic load) consider relationships with foods or diets that are known to differ in their relative glycemic impact (as determined from standardized testing), but these also do not quantify outcomes in relation to the actual levels and variation in PPG over a sustained period of intervention or observation.

Our finding that PPG, as estimated by the total AUC for glucose following meals, seems to be the main contributor to HbA1c in non-diabetic individuals provides a link between PPG and HbA1c that supports the notion that lower PPG is beneficial in terms of preventing future diabetes and reducing risk for cardiovascular disease4, 18, 19. However, in our study population each SD higher AUC was associated with a 0.2%-point (2 mmol/mol) higher HbA1c, indicating that the magnitude of the association was rather modest.

Another aspect of PPG is glycemic variability, which was associated with HbA1c in individuals with non-insulin-treated T2D, but not in individuals without diabetes. In the non-diabetic population mean MAGE was 1.5, which is 2–3 times lower than in the diabetes population. Other studies have estimated MAGE to be between 1.6 and 1.8 in non-diabetic individuals21–23, underscoring that the non-diabetic individuals included in the ADAG study are healthier than the general non-diabetic population.

Overall, we found that preprandial and PPG explained an equal amount of variance in HbA1c in individuals with T2D. Furthermore, glycemic features explained a much larger proportion of the variation in those with T2D than in the non-diabetic population. Other studies using CGM for assessment of glycemia under free-living conditions have also found equal contributions of fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia to HbA1c in patients with T2D, but with a tendency of a greater contribution of PPG at lower HbA1c concentrations and higher contribution of fasting hyperglycemia at higher HbA1c concentrations24–26. The latter result is in accordance with the findings by Monnier et al.9 who suggested that the relative contribution of PPG decreased, whereas the relative contribution of fasting glucose increased, from the lowest to the highest HbA1c quintile among non-insulin-treated T2D patients with HbA1c ranging from ~6 to 12% (42–108 mmol/mol). The use of CGM to measure real-life exposures in the entire study population and the exclusion of individuals treated with insulin in our study are likely to explain the differences between our results and the results by Monnier et al9.

A limitation of our study was the observational design, which limited the possibility to study whether differences in PPG exposures were caused by lifestyle behaviors or use of oral glucose-lowering medications (in T2D only) during the measurement periods or whether they were due to pre-existing glucose intolerance/insulin resistance. We used “pre-breakfast” glucose concentrations as baseline in the calculation of the incremental AUC, which appeared higher than the fasting glucose concentrations measured during screening. Accordingly, the true PPG exposures may have been underestimated and the pre-breakfast exposures overestimated in our study. Another limitation was that information on physical activity and dietary intake was not collected concomitant with the CGM periods. Such information would be relevant to collect in future studies, particularly in individuals without diabetes, in order to understand how different foods, eating patterns, or exercise bouts as well as timing of eating affect daily blood glucose concentrations, peak glucose, and overall glycemia.

In conclusion, we found that PPG exposure contributed more than preprandial glucose or glucose variability to variation in HbA1c in non-diabetic individuals, whereas preprandial glycemia and postprandial glycemia contributed equally to the variation in HbA1c in individuals with T2D. We could only explain one-third of the variance in HbA1c by glycemic factors, age, sex, BMI, and ethnicity among individuals without diabetes, whereas these factors explained nearly 80% of the variance in HbA1c among non-insulin-treated T2D patients with HbA1c concentrations ≥6.5%. Knowledge from this study can be useful to predict clinically meaningful effects on HbA1c of dietary interventions targeting PPG in non-diabetic and non-insulin-treated individuals with T2D with a wide range of glycemic control.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the ADAG study group and the ADAG study investigators as well as all the participants who took part in the study. The ADAG study was supported by research grants from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Financial support for this work was provided by Abbott Diabetes Care, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Safoni-Aventis Netherlands, Merck & Company, Lifescan, and Medtronic Minimed. Supplies and equipments were provided by Medtronic Minimed, Lifescan, and Hemocue. D.V. was financially supported by Unilever during this work. K.F. was supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Authors contributions

K.F. and D.V. researched data and drafted first version of the manuscript. D.V. performed the statistical analyses. R.B. collected data and contributed to interpretation and discussion of results. M.A. and D.J.M contributed to development of hypotheses and contributed to interpretation and discussion of results. D.V. and K.F. are guarantors of this work and as such take responsibility for the content of the article. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

K.F., R.B. and D.V. declare no conflicts of interest. D.J.M. and M.A. are employed by Unilever, which manufactures and sells commercial food products.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41387-018-0047-8).

References

- 1.Gallagher EJ, Le Roith D, Bloomgarden Z. Review of hemoglobin A(1c) in the management of diabetes. J. Diabetes. 2009;1:9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2009.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coban E, Ozdogan M, Timuragaoglu A. Effect of iron deficiency anemia on the levels of hemoglobin A1c in nondiabetic patients. Acta Haematol. 2004;112:126–128. doi: 10.1159/000079722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tancredi M, et al. Excess mortality among persons with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1720–1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selvin E, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:800–811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong GC, Ye MX, Cheng JH, Zhao Y, Gong JP. HbA1c and risks of all-cause and cause-specific death in subjects without known diabetes: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24071. doi: 10.1038/srep24071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos-Oliveira R, et al. Haemoglobin A1c levels and subsequent cardiovascular disease in persons without diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1327–1334. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borg R, et al. Real-life glycaemic profiles in non-diabetic individuals with low fasting glucose and normal HbA1c: the A1C-Derived Average Glucose (ADAG) study. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1608–1611. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1741-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaak EE, et al. Impact of postprandial glycaemia on health and prevention of disease. Obes. Rev. 2012;13:923–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA(1c) Diabetes Care. 2003;26:881–885. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathan DM, et al. Translating the A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1473–1478. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Service FJ, et al. Mean amplitude of glycemic excursions, a measure of diabetic instability. Diabetes. 1970;19:644–655. doi: 10.2337/diab.19.9.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonnell CM, Donath SM, Vidmar SI, Werther GA, Cameron FJ. A novel approach to continuous glucose analysis utilizing glycemic variation. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2005;7:253–263. doi: 10.1089/dia.2005.7.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danne T, et al. International Consensus on Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1631–1640. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snieder H, et al. HbA(1c) levels are genetically determined even in type 1 diabetes: evidence from healthy and diabetic twins. Diabetes. 2001;50:2858–2863. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Færch K, Borch-Johnsen K, Vaag A, Jørgensen T, Witte D. Sex differences in glucose levels: a consequence of physiology or methodological convenience? The Inter99 study. Diabetologia. 2010;53:858–865. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gould BJ, Davie SJ, Yudkin JS. Investigation of the mechanism underlying the variability of glycated haemoglobin in non-diabetic subjects not related to glycaemia. Int. J. Clin. Chem. 1997;260:49–64. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(96)06508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alssema M, et al. Diet and glycaemia: the markers and their meaning. A report of the Unilever Nutrition Workshop. British. J. Nutr. 2015;113:239–248. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514003547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barclay AW, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk—a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;87:627–637. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong JY, Zhang L, Zhang YH, Qin LQ. Dietary glycaemic index and glycaemic load in relation to the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2011;106:1649–1654. doi: 10.1017/S000711451100540X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holman RR, et al. Effects of acarbose on cardiovascular and diabetes outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease and impaired glucose tolerance (ACE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:877–886. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanefeld M, Sulk S, Helbig M, Thomas A, Kähler C. Differences in glycemic variability between normoglycemic and prediabetic subjects. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2014;8:286–290. doi: 10.1177/1932296814522739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma CM, et al. Glycemic variability in abdominally obese men with normal glucose tolerance as assessed by continuous glucose monitoring system. Obesity. 2011;19:1616–1622. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Ym, et al. Glycemic variability in normal glucose tolerance women with the previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2015;7:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim LL, et al. Relationship of glycated hemoglobin, and fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Malaysia. J. Diabetes Invest. 2017;8:453–461. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JS, et al. Contribution of postprandial glucose to excess hyperglycaemia in Asian type 2 diabetic patients using continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2011;27:79–84. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang X, et al. Contributions of basal glucose and postprandial glucose concentrations to hemoglobin A1c in the newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes—the Preliminary Study. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2015;17:445–448. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.