Abstract

Background/Aims

Sociocultural and familial factors associated with weight bias internalization (WBI) are currently unknown. The present study explored the relationship between interpersonal sources of weight stigma, family weight history, and WBI.

Methods

Participants with obesity (N = 178, 87.6% female, 71.3% black) completed questionnaires that assessed the frequency with which they experienced weight stigma from various interpersonal sources. Participants also reported the weight status of their family members and completed measures of WBI, depression, and demographics. Participant height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index (BMI).

Results

Linear regression results (controlling for demographics, BMI, and depression) showed that stigmatizing experiences from family and work predicted greater WBI. Experiencing weight stigma at work was associated with WBI above and beyond the effects of other sources of stigma. Participants who reported higher BMIs for their mothers had lower levels of WBI.

Conclusion

Experiencing weight stigma from family and at work may heighten WBI, while having a mother with a higher BMI may be a protective factor against WBI. Prospective research is needed to understand WBI's developmental course and identify mechanisms that increase or mitigate its risk.

Keywords: Sociocultural factors, Family history, Weight bias internalization, Weight stigma

Introduction

Weight bias is an insidious form of prejudice marked by derogatory attitudes toward and negative stereotypes about individuals with obesity (e.g., lazy and lack willpower) [1, 2]. Some individuals with obesity internalize societal weight bias by applying negative stereotypes to themselves and self-stigmatizing [3]. This weight bias internalization (WBI) is associated with a host of negative mental and physical health outcomes, including low self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, depression and anxiety, reduced physical activity, and poor health-related quality of life [4]. WBI may also mediate or moderate the effects of experiencing weight discrimination on physical health outcomes [5, 6]. A recent study, for example, found evidence of increased odds of metabolic syndrome among individuals with high levels of WBI [7]. Investigators have called for greater attention to addressing WBI in clinical care settings [8].

Recent estimates suggest that approximately 40% of US adults with overweight and obesity internalize weight bias to some degree [9]. Little is known about why some individuals with obesity internalize weight bias while others do not. People who report direct experiences with weight stigma (e.g., discrimination or teasing/bullying), as compared to those who do not, have higher levels of WBI [6, 9], and research suggests that the cognitive interpretation of these experiences contributes to WBI [10]. Persons with certain demographic characteristics - namely white women - also seem more likely than others to internalize weight bias [7, 9, 11].

Currently, investigators do not know whether the source of weight stigma (e.g., family member versus employer) plays a role in determining the degree of WBI. For example, weight-stigmatizing messages from family members may have a particularly potent effect on a person's self-concept [12]. Family is often a primary source of support, and feedback about weight may be taken more seriously (and thus internalized) if received from family members versus distant acquaintances or strangers. This may be especially true if negative messages about weight are received at a young age, when identity is forming [12, 13]. Alternatively, reminders of institutional stigma (such as experiencing discrimination in the workplace) may be particularly damaging to one's self-concept by threatening aspirations for success and achievement, thus leading to beliefs that one may be ‘held back’ due to weight, with consequent internalized blame and self-stigma [14].

Family weight history has also yet to be explored as a risk or protective factor for WBI. Having family members with obesity could be a protective factor against WBI, since obesity may be less stigmatized in an environment in which it is more prevalent [15]. Conversely, if family members are dissatisfied with having a higher body weight and have internalized weight-stigmatizing attitudes themselves, these messages may be transmitted to other family members, thus increasing risk for internalization [16].

Sutin and Terraciano [17] recently investigated the relationship between sources of weight stigma and depression in a nationally representative sample. Results suggested that all sources of stigma, except strangers, were related to increased depression. This study also found increased depressive symptoms among participants who reported experiencing stigma from a greater number of interpersonal sources. Another study in a smaller sample found that stigma from strangers was associated with the most negative affect [18]. Apart from these mixed findings of affective outcomes, no study to date has identified the effects of different sources of weight stigma on the distinct outcome of WBI. Identifying sociocultural and familial factors associated with WBI may help researchers and clinicians to develop a WBI ‘phenotype,’ which is crucial to advancing efforts to address this problem and its related health consequences.

The current study aimed to: i) determine the impact of different sources of weight stigma on WBI and ii) explore the effects of family weight history on WBI. We predicted that experiencing weight stigma from family members would be associated with heightened WBI. By contrast, we predicted that having family members with higher BMIs would be a protective factor against WBI.

Participants and Methods

Participants were 178 adults with obesity recruited from the community to participate in a weight loss trial described previously [19]. Eligible participants had a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 33 kg/m2 (or ≥ 30 kg/m2 with comorbidities) and ≤ 55 kg/m2 and were age 21–65 years. They also were free of current major depression (or antidepressant medication); suicidal ideation; type I or type II diabetes; uncontrolled cardiometabolic disease (e.g., hypertension); or medical conditions that contraindicate weight loss. The institutional review board approved all procedures.

Questionnaires were administered online (via REDcap) or in paper form up to 2 weeks prior to the start of the program. Height and weight were measured at a screening visit, and weight was assessed again during the first week of the program (prior to any weight loss intervention). Only baseline measures from the clinical trial were included in the current study.

Measures

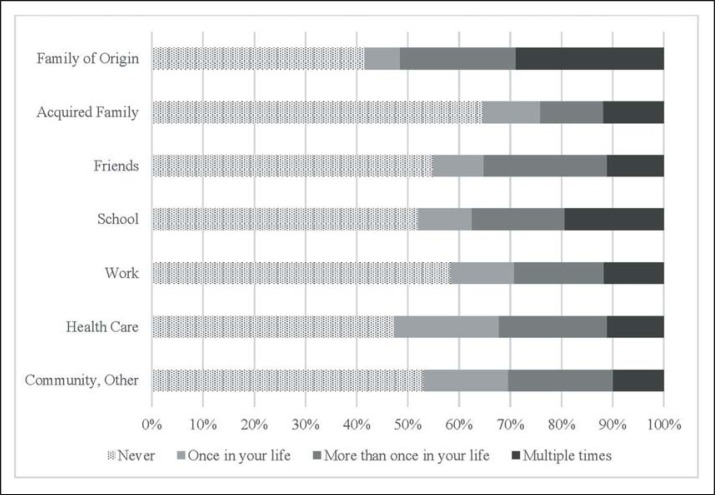

The Interpersonal Sources of Weight Stigma scale [1] assessed the frequency (i.e., never, once in your life, more than once in your life, or multiple times) with which participants reported experiencing weight stigma from 22 sources. Sources of stigma were grouped into seven conceptually based categories: family of origin (e.g., mother); acquired family (e.g., spouse); friends; school; work; health care; and community/other. A dichotomous variable (yes/no) was created for each stigma category, based on endorsement of experiencing stigma from any source within each category. To assess the effects of repeated or chronic stigma (rather than isolated incidents), only participants who responded ‘more than once’ or ‘multiple times' were coded as having experienced stigma. Additionally, to assess the effects of multiple sources of stigma on WBI, a composite score (0–7) was calculated by summing the stigma category variables. Higher composite scores, thus, indicated a greater number of reported interpersonal sources of weight stigma.

Participants also completed items from the Weight and Lifestyle Inventory (WALI) that assessed the heights and weights of their biological parents during their parents' middle adult years (from which BMI was calculated) as well as additional items that asked if any of their siblings or grandparents were ‘overweight or obese’ [20]. These measures are widely used in clinical assessments of treatment-seeking patients with obesity and have shown to be reliable in prior research [21]. Two dichotomous variables (yes/no) were created to designate i) siblings and ii) grandparents with overweight/obesity. WBI was measured with the well-validated Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS; 1–7 scale) [3, 22]. Due to previous research showing that WBI is related to yet distinct from depression [3], depressive symptoms were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; 0–27 scale) [23]. Higher scores on the WBIS and PHQ-9 indicate greater WBI and depressive symptoms, respectively. Demographic characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, gender, and years of education) were self-reported.

Statistical Analyses

Data were checked for normality and outliers (using interquartile range). PHQ-9 scores were transformed with the natural log to meet assumptions of normality. Three outliers for mother's BMI and eight outliers for father's BMI were removed. Missing data can be attributed to participants' omission of specific items. Participants with missing data were excluded only from specific analyses for which relevant items were missing.

To replicate prior findings [1, 17], the frequencies with which participants reported stigma from each source category were computed. Separate linear regression models were used to test each source category as a predictor of WBI. Participant age, race, ethnicity, gender, education, and BMI were included as covariates. In order to determine the effects of the predictor variables on WBI above and beyond the effects of depressive symptoms, analyses were conducted with and without depressive symptoms as a covariate. Another regression model that included all sources of stigma (and all covariates) was constructed to determine their conditional impact on WBI. An additional regression model was also included to test the effects of the composite score (representing the number of sources of stigma) on WBI, controlling for all covariates. Finally, to determine whether a family history of overweight/obesity predicted WBI, four regression models that included each of the four family weight history variables (and covariates) were constructed with WBIS scores as the dependent variable.

Results

Participants were 178 adults aged 21–64 years (mean = 44.2 ± 11.2 years); 71.3% were black, 21.9% white, and 6.7% ‘other’; 6.2% were Hispanic; 87.6% were female; and the mean BMI was 40.9 ± 5.9 kg/m2. The mean WBIS score was 3.6 ± 1.1 (n = 164), and the mean PHQ-9 score was 4.9 ± 4.8 (n = 171). Average reported parents' BMIs were 31.4 kg/m2 for mothers (n = 145) and 29.7 kg/m2 for fathers (n = 113). Of the participants who reported their other family members' weight statuses, 61.0% (105 of 172 responses) reported having a grandparent with overweight/obesity, and 72.3% (120 of 166 responses) reported having a sibling with overweight/obesity.

Frequency and Number of Stigma Sources

Figure 1 presents the frequencies of reported weight stigma from each source category. Overall, family of origin and health care practitioners were the leading sources of any frequency of weight stigma. Repeated instances of stigma were most commonly reported as coming from family of origin, school, and friends, followed by health care and community/other. Work and acquired family were the least frequent sources of repeated stigma.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of weight stigma by source. Note: Ns ranged from 170 to 172 for each source category.

The composite score, indicating the number of source categories from which participants experienced repeated weight stigma, ranged from 0 to 7, with a mean of 2.4 ± 2.2 (n = 171). (Composite scores for four participants were computed with 1 missing item (i.e., 14% of the items were missing). Results were consistent with and without including these participants in the analyses.) Overall, 24.6% of participants reported that they did not experience weight stigma from any category; 19.9% reported experiencing weight stigma from one category, 16.4% from two categories, and 39.2% from three or more source categories.

Effects of Stigma Sources and Family Weight History

Table 1 presents the regression results for the effects on WBI of repeated weight stigma from each source category. Black participants had lower WBIS scores than white participants (3.4 ± 1.1 vs. 4.2 ± 1.1; p < 0.001). We conducted additional analyses testing for racial differences (black vs. not black) for all variables. Analysis of variance and logistic regression models showed no significant differences by race in reports of weight stigma from each interpersonal source, the composite score, or family weight history. Separate regression analyses that included the interaction between race and each predictor variable (i.e., sources of stigma, the composite score, and family weight history variables) showed that race did not moderate the effects on WBI.

Table 1.

Effects of each source of stigma on weight bias internalization#

| Source of stigma | Separate regression models |

Full regression model |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | a | b | |

| Family of origin | 0.24** | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Acquired family | 0.27*** | 0.20** | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Friends | 0.20* | 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.11 |

| School | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Work | 0.31*** | 0.22** | 0.26* | 0.20* |

| Health care | 0.17* | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Community, other | 0.05 | <0.01 | −0.16 | −0.13 |

Standardized beta coefficients are presented. Separate regression models include only one source of stigma. The full regression model includes all sources of stigma. All analyses control for age, race, ethnicity, sex, and BMI. Ns for separate regression models range from 146 to 149. N = 144 for full regression model.

aAnalyses do not control for depression. bAnalyses control for depression.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p ≤ 0.001.

PHQ-9 scores were positively associated with WBIS scores in all regression models (p values < 0.001). When depression was not included in the models, family of origin, acquired family, friends, health care, and work sources of stigma were associated with greater WBIS scores; when depression was included, only acquired family and work sources were significant predictors (family of origin became marginally significant; p = 0.063). When all sources of stigma were included in the same regression model, only work was associated with higher WBIS scores (p = 0.015 without PHQ-9; p = 0.043 with PHQ-9; see table 1). Additionally, the composite score significantly predicted WBIS scores when controlling for all covariates, such that participants who reported experiencing weight stigma from more categories of interpersonal sources had higher levels of WBI (n = 148; without PHQ-9, β = 0.29, p < 0.001; with PHQ-9, β = 0.18, p = 0.020). Finally, mother's BMI (but no other family weight variable) was associated with lower WBIS scores when controlling for depression (n = 121; β = −0.19, p = 0.028; without PHQ-9, β = −0.18, p = 0.060).

Discussion

WBI is highly prevalent and consistently associated with negative mental and physical health outcomes [3, 9], yet little research has examined sociocultural and familial factors associated with this form of self-stigma. The current study evaluated the roles of interpersonal sources of weight stigma and family weight history in accounting for WBI. Consistent with prior research [1, 17], participants reported that family members, health care practitioners, and people in the community were frequent perpetrators of weight stigma, although the most frequent repeated sources of stigma were family, school, and friends.

The sheer number of categorical sources of weight stigma was associated with greater WBI. It may be more difficult to ignore or discount weight-stigmatizing messages when they are delivered by multiple people across various settings, thus increasing the likelihood of these messages becoming internalized. An alternative explanation is that persons with higher levels of WBI may be more likely to perceive weight-based stigmatization from others in their daily lives.

Participants had lower levels of WBI if their mothers had higher BMIs. It is possible that mothers with higher body weights, as compared with thinner mothers, may model healthy weight-related self-esteem and give more messages of body acceptance. Participants may have also viewed their body weight as more ‘normal’ if raised by a mother who also had obesity, thus protecting them against internalizing body-shaming messages. Further research is needed to identify potential mechanisms by which having a mother with a higher body weight may be a protective factor against WBI.

Experiencing weight stigma from family and work had significant effects on WBI, even when controlling for depression. Stigma at work in particular was associated with higher WBI over and above the effects of all other sources. Experiencing weight stigma at work may lead to greater self-stigma and blame due to threatening one's livelihood and potentially feeling helpless to stop it. This finding emphasizes the importance of enacting workplace policies and legislation to prevent weight stigma within employment settings. The public largely supports policies prohibiting weight discrimination [24], and preliminary evidence suggests such policies could diminish WBI by both reducing instances of stigmatization and affirming a sense of justice [14]. Future research should evaluate not only the socioeconomic consequences of enacting such policies, but also their effects on psychological well-being and the associated health consequences of WBI.

The current study assessed the relationship between sociocultural and familial factors and WBI in a treatment-seeking sample. Typically, individuals with obesity who seek treatment have heightened levels of psychological distress compared to the general population [25]. However, WBI scores in the current sample were lower than in some prior studies of WBI in clinical samples [26, 27]. This may have been due to higher representation of black adults in the present sample than in prior studies on this topic [28], which represents a strength of this study. Black participants had lower WBIS scores than non-black participants. However, additional analyses did not reveal racial differences in reported interpersonal sources of weight stigma or family weight history, nor did race moderate the effects of these factors on WBI. Future studies in this area should continue to include greater racial diversity in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of WBI.

WBI scores may also have been lower in the present sample due to the exclusion of individuals with major depression or on antidepressant medications. Depression is robustly associated with WBI and may mediate its relationship with poor health outcomes [29]. By statistically controlling for scores on the PHQ-9, the current study was able to identify correlates of WBI independent of depressive symptoms. Future studies should include participants with more severe levels of depression in order to further test the relationship between this mental health outcome and weight stigma experiences and internalization.

This study was limited by its cross-sectional nature, which precludes conclusions about causality. For example, it is possible that persons with high levels of WBI are more prone to perceiving weight stigmatization in workplace settings. Ultimately, prospective studies are needed to determine the developmental course of WBI in relation to experiences of stigma.

Conclusions

This study is the first to identify potential sociocultural and familial factors associated with the internalization of weight bias. Experiencing weight stigma from family was associated with WBI, although work emerged as the most influential source of stigma. The total number of interpersonal sources of weight stigma was also associated with WBI. Conversely, having a mother with a higher BMI appeared to be a protective factor against WBI. Further research is needed to understand the developmental course of WBI, and to identify mechanisms by which weight stigma in the workplace and family weight history influence the internalization of weight-based stigma.

Funding

This study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Eisai Co (TAW). RLP's work on this paper was partially supported by a mentored patient-oriented research career development award from NHLBI/NIH (#K23HL140176). AMC was supported by an NRSA postdoctoral fellowship from the NINR/NIH (#T32NR007100).

Disclosure Statement

RLP discloses serving as a consultant to Weight Watchers. TAW discloses serving on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and Weight Watchers as well as receiving grant support, on behalf of the University of Pennsylvania, from Eisai Co and Novo Nordisk. JST discloses serving as a consultant for Novo Nordisk. AMC discloses receiving grant support from Shire Pharmaceuticals. RIB discloses serving as a consultant to Eisai Co. None of the other authors declares any conflicts.

References

- 1.Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1802–1815. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearl RL. Weight bias and stigma: public health implications and structural solutions. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2018;12:146–182. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durso LE, Latner JD. Understanding self-directed stigma: development of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16((suppl 2)):S80–S86. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papadopoulos S, Brennan L. Correlates of weight stigma in adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic literature review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:1743–1760. doi: 10.1002/oby.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latner JD, Barile JP, Durso LE, O'Brien KS. Weight and health-related quality of life: the moderating role of weight discrimination and internalized weight bias. Eat Behav. 2014;15:586–590. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearl RL, Puhl RM, Dovidio JF. Differential effects of weight bias experiences and internalization on exercise among women with overweight and obesity. J Health Psychol. 2015;20:1626–1632. doi: 10.1177/1359105313520338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearl RL, Wadden TA, Hopkins CM, Shaw JA, Hayes M, Bakizada Z, Alfaris N, Chao AM, Pinkasavage E, Berkowitz RI, Alamuddin N. Association between weight bias internalization and metabolic syndrome among treatment-seeking individuals with obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:317–322. doi: 10.1002/oby.21716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahan S, Puhl RM. The damaging effects of weight bias internalization. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;25:280–281. doi: 10.1002/oby.21772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puhl RM, Himmelstein MS, Quinn DM. Internalizing weight stigma: prevalence and sociodemographic considerations in US adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26:167–175. doi: 10.1002/oby.22029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearl RL, Puhl RM. The distinct effects of internalizing weight bias: an experimental study. Body Image. 2016;17:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boswell RG, White MA. Gender differences in weight bias internalization and eating pathology in overweight adults. Adv Eat Disord. 2015;3:259–268. doi: 10.1080/21662630.2015.1047881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunger J, Tomiyama A. Weight labeling and obesity: a longitudinal study of girls aged 10 to 19 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:579–580. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stunkard A, Burt V. Obesity and body image II: age at onset of disturbances in the body image. Am J Psychiatry. 1967;123:1443–1447. doi: 10.1176/ajp.123.11.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearl RL, Puhl RM, Dovidio JF. Can legislation prohibiting weight discrimination improve psychological well-being? A preliminary investigation. Anal Soc Iss Public Pol. 2017;17:84–104. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crosnoe R. Gender, obesity, and education. Sociol Educ. 2007;80:241–260. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grusec J. Parental socialization and children's acquisition of attitudes. In: Bornstein M, editor. H and book of Parenting: Practical Issues in Parenting. 2nd ed. vol 5. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutin A, Terracciano A. Sources of weight discrimination and health. Stigma Health. 2017;2:23–27. doi: 10.1037/sah0000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vartanian L, Pinkus R, Smyth J. The phenomenology of weight stigma in everyday life. J Context Behav Sci. 2017;3:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tronieri J, Alfaris N, Chao A, Pearl R, Alamuddin N, Bakizada Z, Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA. Lorcaserin plus lifestyle modification for weight loss maintenance: rationale and design for a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;59:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wadden T, Foster G. Weight and lifestyle inventory. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14((suppl 2)):99S–118S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crerand C, Wadden T, Sarwer D, Fabricatore A, Kuehnel R, Gibbons L, Brok JR, Williams NN. A comparison of weight histories in women with class III vs. class I-II obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14((suppl 3)):63S–69S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hubner C, Schmidt R, Selle J, Kohler H, Muller A, deZwaan M, et al. Comparing self-report measures of internalized weight stigma: the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire versus the Weight Bias Internalization Scale. PLos One. 2016;11:e0165566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic severity measures. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puhl RM, Suh Y, Li X. Legislating for weight-based equality: national trends in public support for laws to prohibit weight discrimination. Int J Obes. 2016;40:1320–1324. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzgibbon M, Stolley M, Kirschenbaum D. Obese people who seek treatment have different characteristics than those who do not seek treatment. Health Psychol. 1993;12:342–345. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.5.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durso LE, Latner JD, Ciao AC. Weight bias internalization in treatment-seeking overweight adults: psychometric validation and associations with self-esteem, body image, and mood symptoms. Eat Behav. 2016;21:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carels RA, Wott CB, Young KM, Gumble A, Koball A, Oehlhof MW. Implicit, explicit and internalized weight bias and psychological maladjustment among treatment-seeking adults. Eat Behav. 2010;11:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Himmelstein M, Puhl R, Quinn D. Intersectionality: an understudied framework for addressing weight stigma. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearl RL, White MA, Grilo CM. Weight bias internalization, depression, and self-reported health among overweight binge eating disorder patients. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:E142–148. doi: 10.1002/oby.20617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]