Abstract

To investigate the effect of yoga on negative affect (an eating disorders risk factor), 38 individuals in a residential eating disorder treatment program were randomized to a control or yoga intervention: 1 hour of yoga before dinner for 5 days. Negative affect was assessed pre- and post-meal. Mixed-effects models compared negative affect between groups during the intervention period. Yoga significantly reduced pre-meal negative affect compared to treatment as usual; however, the effect was attenuated post-meal. Many eating disorders programs incorporate yoga into treatment. This preliminary evidence sets the stage for larger studies examining yoga and eating disorder treatment and prevention.

In residential facilities for eating disorders treatment, various forms of complementary and alternative approaches are increasingly being incorporated into treatment (Frisch, Herzog, & Franko, 2006). One of these approaches is yoga, which, despite having a long history, has only recently begun to be studied for its effects on health. Yoga has the potential to promote embodiment, i.e., the ability to experience the body from within, through incorporation of mindfulness, physical movement, utilization of the breath, and other techniques. Thus, yoga has promise for the treatment of eating disorders in which there is often a sense of disconnection from one’s body (Diers, 2016).

Though practitioners and eating disorder treatment team members have observed positive outcomes related to clients practicing yoga, research using yoga as an intervention in eating disorders is sparse (Klein & Cook-Cottone, 2013; Neumark-Sztainer, 2014a). Yoga has been associated with reduced factors of potential relevance to eating disorders including: self-objectification (Cox, Ullrich-French, Cole, & D’Hondt-Taylor, 2015; Daubenmier, 2005; Prichard & Tiggemann, 2008); body dissatisfaction (Daubenmier, 2005; Delaney & Anthis, 2010; Dittmann & Freedman, 2009; Flaherty, 2014; Neumark-Sztainer, Eisenberg, Wall, & Loth, 2011); and drive for thinness (Cook-Cottone, Beck, & Kane, 2008; Mitchell, Mazzeo, Rausch, & Cooke, 2007). In sum, there is evidence to support the belief that yoga may be a novel and favorable intervention for those with eating disorders; however, rigorous work is needed.

Thus far, to the best of our knowledge, only three randomized controlled trials have been published that evaluated the effectiveness of yoga in eating disorder populations (Carei, Fyfe-Johnson, Breuner, & Brown, 2010; McIver, O’Halloran, & McGartland, 2009). McIver and colleagues (2009) recruited a community sample meeting diagnostic criteria for binge eating disorder (BED), and found that 12 weeks of yoga significantly reduced self-reported number of binges in those randomized to the yoga group as compared to the control group. Carei et al. (2010), studied adolescents diagnosed with eating disorders receiving outpatient treatment and found that 8 weeks of twice weekly yoga taught on an individual basis improved scores on the Global Scale of the Eating Disorder Examination Interview at follow-up compared with a control group. A third experimental trial did not find a difference in eating disorder symptom reduction between yoga and a dissonance-based intervention group compared to a control group in college women with body dissatisfaction over a 6-week period (Mitchell et al., 2007). However, the sufficiency of the dosage and duration of yoga (one 45-minute session a week over 6 weeks) has been questioned (Klein & Cook-Cottone, 2013). The aforementioned experimental evidence has investigated yoga in outpatient eating disorder clients, adolescents, and college females. In individuals with more severe eating disorders, the role of yoga in treatment has not been studied to date to the best of our knowledge, and yoga is a popular treatment modality in residential treatment centers (Frisch et al., 2006). A review of the role of yoga in eating disorders treatment called for more research in this promising area, specifically using strong study designs (Neumark-Sztainer, 2014b).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of yoga on mealtime negative affect and eating disorder symptoms, using a randomized, controlled study design, during residential eating disorder treatment. We hypothesized that yoga would improve pre-meal negative affect compared with usual residential treatment. We also examined observer-rated anxiety, eating disorder symptoms, and distress tolerance in the two groups to assess trends.

Methods

Participants and measures

The sample was recruited over a period of about 8 months from a 16-bed residential eating disorder treatment facility. Residential facility staff collected the following information upon admission: date of admission to residential treatment, gender, measured height (baseline), measured weight (baseline), and diagnosis (assessed by intake therapist). Newly admitted clients who were medically cleared by the residential MD to participate in yoga were provided with information about the study. Those interested met with a research assistant to go through the consenting process. Once consent was obtained, a baseline survey, consisting of the Emotional Avoidance Questionnaire (EAQ; Taylor, Laposa, & Alden, 2004)) and the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 2008)) was administered. On the following two days, a survey consisting of 10 items assessing negative mood from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) was filled out each client before and after the evening meal. These assessments of the EAQ, EDE-Q, and two days of negative affect pre- and post-meal served as baseline data. The client’s schedule was then updated to reflect their randomization assignment to the yoga group (50 minutes of yoga prior to the evening meal) or the control group (regularly scheduled residential activities such as gardening or supervised free time, e.g., sitting in a common area and talking before dinner) for 5-day intervention period. Each meal table at the residential facility was led by an Eating Disorder Technician/meal coach, who completed a modified version of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAS; Hamilton, 1959)) to evaluate each client’s mealtime behavior daily over the course of the study (2 days of baseline data collection and 5 days of intervention).

The EDE-Q is a 28-item measure that assesses eating disordered cognitions and behaviors and consists of four subscales: restraint, shape concern, weight concern, and eating concern (Fairburn, 2008). The restraint subscale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76) includes five items (e.g., “On how many of the past 28 days … have you had a definite desire to have an empty stomach with the aim of influencing your shape or weight?”, with response options ranging from 0 (no days) to 6 (every day). Shape concern (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) includes eight items asking about how the participant has felt about the shape of their body over the past 28 days, such as “How dissatisfied have you been with your shape?”, with response options differing by item and including the same response options listed above as well as other Likert scales, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (markedly). Weight concern (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) includes 5 items regarding weight such as, “Over the past 28 days … has your weight influenced how you think about (judge) yourself as a person?”, with response options matching those described above, depending on the item. Eating concern (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75) includes five items, with items like “On how many of the past 28 days … have you had a definite fear of losing control over eating?”, again, using the response options described above depending on the item. Participants filled out the EDE-Q twice: after consenting to participate in the study and at the end of the intervention period.

The EAQ is a 20-item measure of distress tolerance with four subscales: avoid positive emotions (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.89; example of an item “I try to keep positive emotions hidden so that other people won’t be aware of them,” negative beliefs about emotions, social concerns about displaying emotion, and avoid negative emotions (Taylor et al., 2004). Responses options are Likert-scale format, ranging from 1 (not true of me) to 5 (very true of me). Participants filled out the EAQ twice: after consenting to participate in the study and at the end of the intervention period.

The Negative Affect portion of the PANAS evaluates 10 emotions (guilty, hostile, ashamed, afraid, irritable, scared, nervous, upset, distressed, jittery) using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely) (Watson et al., 1988). Momentary instructions were used (Indicate to what extent you feel this way right now (that is in the present moment) and Cronbach’s alphas were 0.88 pre-meal and 0.93 post-meal. Participants filled out the Negative Affect portion of the PANAS twice daily (before and after the meal).

The adapted HAS used in this study included 4 items which asked about evidence of thoughts and behaviors related to anxious moods, tension, and behavior (items from the original HAS—Hamilton, 1959), and an additional item included for the purposes of this study: eating anxiety (e.g., picking at foods, cutting foods into small pieces, chewing and spitting out food) and rated a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (severe, grossly disabling). Meal coaches were trained to fill out the HAS after mealtime for each participant for each of the seven days of the study. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Procedure

Thirty-eight newly admitted clients chose to enroll in the study and were randomized to either the yoga group or the control group. The University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

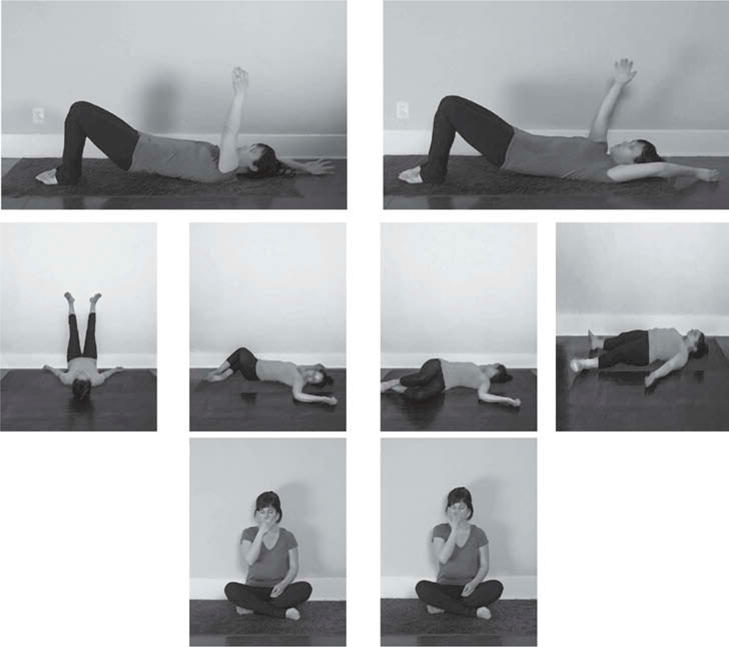

Therapeutic yoga classes were taught for one hour during the 5-day intervention period immediately before the dinner by eating-disorder-sensitive, trained yoga teachers (i.e., Yoga Alliance Registered RYTs at the 200- or 500- level). The training for this sequence occurred at three levels: in-person group instruction, a recorded version of selected postures for reference, and a typed sequence (see Figure 1 caption) to use as a reference to guide consistent instruction. Yoga classes were carefully designed and taught with a unique standing start sequence to meet clients at a heightened anxiety state and begin to reduce this state. A typical standing sequence is depicted by Figure 1. While approximate planned times are provided in the figure caption, it is important to note that there was some variation in accordance with the participants attending the class (i.e., in accordance with familiarity with yoga, emotional issues arising in class, number of attendees, etc.) Classes incorporated integrated movement and breathing techniques aimed at increasing parasympathetic nervous system activation (Streeter, Gerbarg, Saper, Ciraulo, & Brown, 2012), anxiety reduction and reduction of eating disorder thoughts/behaviors. Specific asanas (postures) were highlighted along with focused breathing techniques: Asanas, focused intentions and breathing techniques included: Breath of Joy; Naga Devi (Lion’s Breath, Goddess Pose); Downward Facing Dog, Legs up the Wall, calming and positive self-affirmations and Alternate Nostril Breathing (Iyengar & Menuhin, 1979). Classes ended with a relaxation pose.

Figure 1.

Yoga standing sequence.

Note. Total time is equal to 38 minutes because this doesn’t factor the time it takes for everyone to get settled into class, transition time from pose to pose, or the closing centering of class.

Analysis

One participant withdrew from the yoga group and one from the control group. Baseline characteristics (body mass index [BMI], pre-meal negative affect, post-meal negative affect, observer-rated anxiety, EAQ and EDE-Q subscale scores) were not significantly different between those who withdrew and those who completed the study except for age, with those who withdrew being significantly older (M = 42.5, SD = 0.71) than the rest of the sample (M = 26.7, SD = 8.13, t(36) = –2.71, p < .001). Yoga and control groups were compared on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics using Fisher’s Exact or chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests for continuous variables. Mixed-effects models with random intercepts were used to compare yoga and control groups on daily pre-meal negative affect, post-meal negative affect, and HAS anxiety scores. Linear and quadratic components were included for the intervention period to allow non-linear changes over time. The primary hypotheses were evaluated using the group (yoga vs. control)-by-day interactions, which compare the intervention-period trajectories between groups. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test for differences between the yoga and control groups on EAQ and EDE subscales at end the end of treatment controlling for baseline scores. Intent-to-treat approach to analyses were used for all statistical tests.

Results

Table 1 displays mean baseline characteristics for the yoga group and the control group, and independent samples t-test comparison statistics. The sample was primarily female (97.3% of sample), and though 95% of participants in the yoga group and 100% of participants in the control group were female, this difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test p = .53). The majority of participants in the sample were diagnosed with anorexia nervosa (AN) (22/38 or 58%), followed by a smaller number with bulimia nervosa (BN) (8/38 or 21%) and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) (8/38 or 21%). The proportion of participants with each diagnosis was not significantly different between groups (likelihood ratio test (2) = 1.1, p = .58). Baseline scores on the EDE-Q were indicative of pathology, but were not significantly different between groups (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline comparisons between yoga and control group participants.

| Yoga (n = 20) |

Control (n = 18) |

95% CI for difference

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t(36) | p | LL | UL | Cohen’s d | |

| Age | 26.8 | 10.3 | 26.8 | 8.7 | 0.58 | .57 | −4.13 | 7.4 | 0.19 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.5 | 7.5 | 18.0 | 3.9 | −1.74 | .09 | −7.43 | 0.57 | −0.58 |

| Pre-meal negative affect | 27.9 | 7.3 | 31.5 | 9.1 | 1.37 | .18 | −1.76 | 9.07 | 0.46 |

| Post-meal negative affect | 30.3 | 11.6 | 33.0 | 8.5 | 0.81 | .42 | −4.04 | 9.43 | 0.27 |

| Hamilton Anxiety Scale | 5.3 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 2.8 | 1.80 | .07 | −0.19 | 3.86 | 0.60 |

| EAQ—Avoid positive emotions | 10.6 | 4.7 | 13.1 | 5.8 | 1.50 | .14 | −0.91 | 6.03 | 0.50 |

| EAQ—Negative beliefs about emotions | 16.6 | 5.1 | 16.3 | 4.5 | −0.19 | .85 | −3.45 | 2.85 | −0.06 |

| EAQ—Social concerns about displaying emotion | 17.7 | 4.9 | 18.9 | 4.0 | 0.84 | .41 | −1.75 | 4.19 | 0.28 |

| EAQ—Avoid negative emotions | 19.8 | 2.8 | 18.2 | 3.3 | −1.68 | .10 | −3.68 | 0.34 | −0.56 |

| EDE-Q—Restraint | 3.9 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 0.52 | .61 | −0.69 | 1.15 | 0.17 |

| EDE-Q—Shape concern | 4.7 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 1.1 | 0.41 | .69 | −0.75 | 1.13 | 0.14 |

| EDE-Q—Weight concern | 4.2 | 1.7 | 4.6 | 1.4 | 0.70 | .49 | −0.68 | 1.39 | 0.23 |

| EDE-Q—Eating concern | 4.0 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 1.3 | −0.89 | .38 | −1.33 | 0.52 | −0.30 |

| EDE-Q—Global | 4.2 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 0.24 | .81 | −0.71 | 0.90 | 0.08 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; EAQ = Emotional Avoidance Questionnaire; EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire.

Figure 2 presents pre-meal negative affect across the baseline and intervention periods by group. Average baseline negative affect (days 1 and 2) was not significantly different between groups as noted in Table 1. During the intervention period, the yoga group experienced a significant linear reduction in pre-meal negative affect across days in comparison to the control group (Estimate = −5.3, SE = 2.0, p = .007). During the intervention period, the yoga and control groups also differed in the non-linear patterns of change over time (Estimate = 1.0, SE = 0.4, p = .008). The control group’s negative affect decreased slightly between days 3 and 5, and increased slightly between days 5 and 7. The yoga group’s negative affect increased slightly between days 3 and 5, and decreased slightly between days 5 and 7, mirroring the nonlinear component of affect trajectory of the control group. On the first day after the intervention, average pre-meal negative affect was 21.8 (SD = 8.8) in the yoga group and 28.9 (SD = 9.8) in the control group (t(36) = −2.37, p = .023). On the second day after the intervention, average pre-meal negative affect was 21.6 (SD = 12.0) in the yoga group and 28.2 (SD = 10.0) in the control group (t(36) = −1.84, p = .075).

Figure 2.

Pre-meal negative affect in the yoga and control groups over the study period.

Though BMI (k/m2) was not statistically significantly different between groups at baseline, there was a potentially clinically meaningful difference between groups. Analyses for pre-meal negative affect were rerun controlling for baseline BMI and the significance level and parameter estimates were virtually identical. Although our primary interest was in pre-meal negative affect, we also examined post-meal negative affect. While the general pattern of results is similar for post-meal negative affect, differences were not statistically significant (Linear estimate = −0.30, SE = 2.66, p = .91; Quadratic estimate = 0.07, SE = 0.52, p = .89).

Observer-rated anxiety was measured by the modified version of the HAS filled out by meal coaches (observers). During the intervention period, observers’ ratings showed a significant linear decrease in anxiety in the yoga in comparison to the control group (Estimate = 2.64, SE = 1.24, p = .035). During the intervention period, the yoga and control groups also differed in the non-linear patterns of change over time such that between days 1 and 3 of the intervention, the yoga group’s HAS scores decreased while the control group’s HAS scores remained stable. Between days 3 and 5 of the intervention, the yoga group’s HAS scores increased while the control group’s HAS scores decreased (Estimate = −0.64, SE = 0.24, p = .009).

Given the intensity of the residential treatment both groups were receiving, and the brevity of the yoga intervention, we did not expect to see differences in EAQ or EDE-Q scores, but did conduct assessments. As expected EAQ, and EDE-Q scores did not differ significantly between the yoga and control groups (ps ≥ .05). However, in the yoga group there was a possible trend observed towards measures of both the EAQ and EDE decreasing. Statistical estimates for the EAQ and EDE-Q are noted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results for yoga (n = 20) versus control group (n = 18) ANCOVA on the EAQ and EDE-Q.

| Item | F (dfbetweeen, dfwithin) | p | Partial Eta squared |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAQ—Avoid positive emotions | 0.08 (1, 35) | .77 | 0.02 |

| EAQ—Negative beliefs about emotions | 0.84 (1, 35) | .37 | 0.02 |

| EAQ—Social concerns about displaying emotion | 0.16 (1, 35) | .69 | 0.01 |

| EAQ—Avoid negative emotions | 1.31 (1, 35) | .26 | 0.04 |

| EDE-Q—Restraint | 0.19 (1, 35) | .67 | 0.01 |

| EDE-Q—Shape concern | 1.13 (1, 35) | .30 | 0.03 |

| EDE-Q—Weight concern | 2.33 (1, 35) | .14 | 0.06 |

| EDE-Q—Eating concern | 0.58 (1, 35) | .45 | 0.02 |

| EDE-Q—Global | 1.43 (1, 35) | .24 | 0.04 |

Note. ANCOVA = Analysis of Covariance; EAQ = Emotional Avoidance Questionnaire; EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, we found that residential clients with eating disorders exhibited significantly lower negative affect before dinner when taking a yoga class designed to target eating disorder symptomatology as compared to usual care. This effect was attenuated throughout the meal; however, results for post-meal negative affect were not statistically significant. These findings suggest that a yoga intervention developed for individuals with eating disorders may decrease negative feelings before mealtime in residential eating disorder clients. The findings are particularly striking in that clients only participated in five 1-hour yoga sessions. Since greater negative mood is related to poorer eating disorder symptomatology at meals (Ranzenhofer et al., 2013; Steinglass et al., 2010), yoga may offer a promising way to facilitate recovery in individuals suffering from eating disorders.

In addition to the rigor of the randomized controlled trial study design, the present trial having been conducted in a residential treatment facility is a notable strength. Many treatment facilities have included yoga in their treatment schedule, but may not have the flexibility to implement a treatment that is offered to some clients and not others, making this study ecologically valid. Additionally, we had good retention and equal retention across groups. These strengths are notable in spite of the small sample size, as this was a pilot study. Since yoga was effective in reducing pre-meal negative affect but this effect was attenuated post-meal, not only practicing yoga prior to mealtime, but also integrating principles of yoga during mealtime may be a way to continue the reduction in negative affect during mealtime. Seated yoga postures and breath work could be integrated during mealtime to see if this can help with reduction in eating disorder behaviors and keeping negative affect reduced throughout the meal. Research on the optimal dose, duration, and type of yoga for eating disorder populations will be important moving forward. Additionally, effects were found in a transdiagnostic treatment-seeking sample, indicating that yoga may be of use for eating disorder symptoms that span diagnostic categories, in line with the current research domain criteria (RDoC).

Secondary outcomes for this study included observer ratings of participant’s anxiety and scores on measures assessing distress tolerance and eating disorder symptoms. Observer ratings of client’s anxiety at mealtime did not significantly change by group during the intervention period. Given the short-term nature of the study, the minimal time spent in yoga (approximately 5 hours total) and the fact that both groups were receiving intensive treatment (approximately 70 hours a week of treatment), secondary endpoints of changes in subscales of the EAQ and EDE-Q were not significantly different before and after the intervention when comparing the control and yoga groups. The EDE-Q assesses problematic behaviors and cognitions over a period of the past 28 days, and since the follow-up occurred 9 days after the baseline assessment, it is probable that unless the intervention had a very strong effect on the outcome, an effect would not be detectable. A shorter, 7-day version of the EDE-Q has been published (Gideon et al., 2016) and could be used to alleviate these concerns in future studies. For the EAQ, it is possible that the sample size of this pilot was not sufficient to detect an effect, or that the dose or duration of the yoga intervention did not have change aspects of emotional avoidance. Experimental studies that found significant benefits of yoga on eating disorder related symptoms were of longer duration and measured outcomes that would a longer period of time to change, factors which would make a finding more probable (Carei et al., 2010; McIver et al., 2009), On the other hand, these studies used less severe eating disorder populations so it is possible that yoga has a momentary affect on momentary states (e.g., anxiety) but takes a longer time to affect symptomology or trait-like measures (e.g., distress tolerance). Additionally, in these other studies, control group participants were receiving no (i.e., waitlist) or minimal treatment as compared to the current study, where control group participants received residential care.

Future research investigating how yoga is able to facilitate reduction in negative affect and related outcomes in eating disorder clients may add to the theoretical literature on affect regulation in eating disorders (Lavender et al., 2015). Qualitative feedback from participants in the yoga group, who were surveyed after intervention concluded, indicated that the practice helped instill feelings of calmness and becoming more in tune with themselves and their internal drives (e.g., hunger)—measures of interoception should be included in future research. Eating disorders may be categorized by a dualistic relationship between mind and body (Diers, 2016), while yoga directs attention inward, promoting embodiment (see Douglass, 2010). It will also be important to assess baseline yoga experience, as different levels of exposure to yoga may impact change in outcomes. Finally, future research evaluating yoga’s potential to reduce risk factors for eating disorders (e.g., body image concerns) in relatively “healthy” populations using a randomized controlled design is needed, since observational work suggests potential for prevention.

In conclusion, adding scientific rigor to intuitively appealing complementary and alternative and instated medical approaches is essential to evidence-based practice. Pre-meal negative affect is an important factor to target in residential treatment settings given the associations with eating disorder outcomes (Ranzenhofer et al., 2013; Steinglass et al., 2010). This study serves as groundwork to fuel future research in a promising approach to further the field of eating disorder treatment and prevention.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to Elise Madden, Kara Gavin, Amanda Swygard, and especially Allison Wolf and Stephanie Merek for their valuable contributions and to this study. Thank you to Drs. Scott Crow and Carol Peterson for their help with designing and implementing the study. Thanks to Li Cao for her excellent statistical support. We are also extremely grateful to The Emily Program Yoga instructors for their dedication, time, flexibility, and input.

Funding

The Emily Program Foundation funded this project. The corresponding author was supported by federal grants T32 DK 083250 and T32 MH 082761. This present trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02191995.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report with this funding.

References

- Carei T, Fyfe-Johnson AL, Breuner CC, Brown MA. Randomized controlled clinical trial of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Cottone C, Beck M, Kane L. Manualized-group treatment of eating disorders: Attunement in mind, body, and relationship (AMBR) The Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 2008;33:61–83. doi: 10.1080/01933920701798570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox AE, Ullrich-French S, Cole AN, D’Hondt-Taylor M. The role of state mindfulness during yoga in predicting self-objectification and reasons for exercise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daubenmier JJ. The relationship of yoga, body awareness, and body responsiveness to self-objectification and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29(2):207–219. doi: 10.1111/pwqu.2005.29.issue-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney K, Anthis K. Is women’s participation in different types of yoga classes associated with different levels of body awareness satisfaction? International Journal of Yoga Therapy. 2010;20:62–71. doi: 10.17761/ijyt.20.1.t44l6656h22735g6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diers L. Discovering the role of yoga in eating disorder treatment. Sports, Cardiovascular, and Wellness Nutrition (SCAN) PULSE, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016;35 Retrieved from https://www.emilyprogram.com/blog/discovering-the-role-of-yoga-in-eating-disorder-treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmann KA, Freedman MR. Body awareness, eating attitudes, and spiritual beliefs of women practicing yoga. Eating Disorders. 2009;17(4):273–292. doi: 10.1080/10640260902991111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass L. Thinking through the body: The conceptualization of yoga as therapy for individuals with eating disorders. Eating Disorders. 2010;19(1):83–96. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. 1st. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0) In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty M. Influence of yoga on body image satisfaction in men. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2014;119:203–214. doi: 10.2466/27.50.PMS.119c17z1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MJ, Herzog DB, Franko DL. Residential treatment for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:434–442. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1098-108X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gideon N, Hawkes N, Mond J, Saunders R, Tchanturia K, Serpell L. Development and Psychometric Validation of the EDE-QS, a 12 item short form of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0152744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar BKS, Menuhin Y. Light on yoga: Yoga dipika. New York, NY: Schocken; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Klein J, Cook-Cottone C. The effects of yoga on eating disorder symptoms and correlates: A review. International Journal of Yoga Therapy. 2013;2:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Gordon KH, Kaye WH, Mitchell JE. Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;40:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIver S, O’Halloran P, McGartland M. Yoga as a treatment for binge eating disorder: A preliminary study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2009;17:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Rausch SM, Cooke KL. Innovative interventions for disordered eating: Evaluating dissonance-based and yoga interventions. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:120–128. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1098-108X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D. Yoga and eating disorders: Is there a place for yoga in the prevention and treatment of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviours? Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice. 2014a;2:136–145. doi: 10.1080/21662630.2013.862369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D. Yoga and eating disorders: Is there a place for yoga in the prevention and treatment of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviours? Advances in Eating Disorders. 2014b;2:136–145. doi: 10.1080/21662630.2013.862369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Wall M, Loth KA. Yoga and pilates: Associations with body image and disordered-eating behaviors in a population-based sample of young adults. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:276–280. doi: 10.1002/eat.v44.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard I, Tiggemann M. Relations among exercise type, self-objectification, and body image in the fitness centre environment: The role of reasons for exercise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2008;9:855–866. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranzenhofer LM, Hannallah L, Field SE, Shomaker LB, Stephens M, Sbrocco T, Tanofsky-Kraff M. Pre-meal affective state and laboratory test meal intake in adolescent girls with loss of control eating. Appetite. 2013;68:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass JE, Sysko R, Mayer L, Berner LA, Schebendach J, Wang Y, Walsh BT. Pre-meal anxiety and food intake in anorexia nervosa. Appetite. 2010;55:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeter CC, Gerbarg PL, Saper RB, Ciraulo DA, Brown RP. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Medical Hypotheses. 2012;78:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CT, Laposa JM, Alden LE. Is avoidant personality disorder more than just social avoidance? Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:571–594. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.6.571.54792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]