Abstract

We sought to determine whether sustained poverty is associated with change in body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2) among 4,762 black and white adults from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Household income in the prior year and current BMI were measured at 7 visits between 1990 and 2015. Sustained poverty was the proportion of visits during which household income was below 200% of the federal poverty level (range, 0%–100%). Sustained poverty and BMI were time-updated. Mean age in 1990 was 30 years. In adjusted linear mixed-effects models, every 10% increase in sustained poverty was significantly associated with faster BMI growth among white men (0.004/year, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.008) and white women (0.003/year, 95% CI: 0.000, 0.006), and slower BMI growth among black men (−0.008/year, 95% CI: −0.010, −0.005) and black women (−0.003/year, 95% CI: −0.006, 0.000). In other words, being always versus never in poverty from 1990 to 2015 was predicted to result in greater BMI gain by 1.00 unit and 0.75 units among white men and women and less BMI gain by 2.0 units and 0.75 units among black men and women, respectively. Sustained poverty was a predictor of changes in BMI with differential associations according to race.

Keywords: body mass index, income, obesity, poverty, socioeconomic status

Obesity is a major public health issue and a leading contributor to cardiovascular disease morbidity, mortality, and increased healthcare costs (1–3). About 38% of the US adult population is currently obese (4), with obesity disproportionately affecting minorities and populations with fewer economic resources or living in poverty (5). While the cross-sectional association between low income or poverty and body mass index (BMI) has been extensively explored (5–14), findings have been mixed and inconsistent across studies and across sex and racial groups. For example, among women (8), particularly white women, low income is consistently associated with higher rates of obesity (5). This pattern is less consistent among black women (15) and white men (5). On the other hand, among black men, low income has been shown to have an inverse relationship with obesity (5).

Past studies that have assessed the relationship between income or poverty and changes in BMI have done so at only few time points (16, 17)—repeated measures of socioeconomic status over longer periods of time are seldom available (18–21). Furthermore, to our knowledge, none have explored the association of cumulative or sustained exposure to low income. Yet income has a dynamic nature (22, 23), especially going from young adulthood into midlife. Thus, consideration of sustained exposure to poverty is important because it captures changes in poverty status, and because sustained rather than momentary exposure to poverty may better capture the accumulation of risk associated with poverty. Similarly, BMI changes with age and likely in a curvilinear fashion. Because both income and BMI change through the life course, it is of interest to determine the nature of their association when both income and BMI are assessed long-term, repeatedly, and with appropriate consideration for temporality. The latter is particularly important because reverse causation has long been recognized as a potential threat to causal inference in observational studies of socioeconomic status and health. For example, it has been suggested that the association between income and BMI may in part be due to downward social drift (24)—meaning that being overweight or obese results in a loss of earned income (25)—particularly for women (24, 26).

We aimed to overcome some of the limitations in the previous literature by using data from a large, ongoing cohort of black and white adult men and women in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Both household income during the past 12 months and current BMI (thus naturally lagged) were repeatedly measured between 1990 and 2015 at a total of 7 time points. We conceptualized income/poverty and BMI with a clear life-course framework (i.e., by capturing cumulative rather than momentary exposure to poverty and by updating this cumulative measure at each time point over 25 years). The goals of this study were 2-fold: to examine the longitudinal association between time-updated sustained poverty and changes in BMI from 1990 to 2015, and to rule out reverse causation as a sole explanation of the findings. Income and BMI are rarely characterized together with such a clear life-course framework; by doing so, this study can provide a deeper understanding for their longitudinal relationship.

METHODS

Study population

CARDIA is an ongoing longitudinal cohort study that enrolled 5,114 participants aged 18–30 years in 1985–86 from 4 field centers: the University of Alabama at Birmingham (Birmingham, Alabama), the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota), Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois), and Kaiser Permanente (Oakland, California). Recruitment was balanced within center according to sex, age, and education. Individuals were asked to participate at baseline and were reexamined in 1987, 1990, 1992, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. Standardized protocols were used to gather demographic, social, and clinical data for each follow-up visit. Details of the study have been described elsewhere (27). Appropriate informed consent was obtained from each study participant. The study was approved by the institutional review boards from each field center and the coordinating center.

Measurement of sustained poverty

Income data were collected in 1990, 1992, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. At these examinations, pretax household income for the past 12 months from all sources was self-reported and recorded in income categories. Thus income in past year was naturally lagged from the outcome variable (current BMI). The income-category midpoint was chosen as the participant’s income for that year (see Appendix Table 1). Using income-category midpoint and family size at each examination period, Census Bureau federal poverty level thresholds (28) were used to identify whether participants’ income was less than 200% of the federal poverty level for that year. Having an income <200% of the federal poverty level was defined as being in poverty for that year/study visit (29). The income cutoffs for 200% of the federal poverty level for a 4-person household were $26,718 in 1990, $28,670 in 1992, $31,138 in 1995, $35,206 in 2000, $39,942 in 2005, $44,630 in 2010, and $45,164 in 2015. At each visit, sustained poverty was then defined as the proportion of visits that a participant was living in poverty between 1990 (our study baseline) and that visit. Sustained poverty (i.e., proportion of total visits in poverty) was updated at successive visits and thus treated as a time-varying exposure variable. At any study visit, sustained poverty ranged from 0 (never in poverty) to 1 (in poverty at all previous visits).

Measurement of BMI and other covariates

At each examination between 1990 and 2015, participants’ height and weight were measured while wearing light clothes and no shoes. BMI was calculated as weight(kg)/height (m)2. If a woman reported being pregnant, her BMI was set to missing. CARDIA participants reported their sex, race, marital status, years of education completed, and the years of education their parents completed. Highest level of education from either parent was used. Smoking status (defined as never, current, or former) and physical activity were ascertained by interview at each study examination. Total amount of exercise in units was calculated using reports of the amount of time per week spent in 13 categories of physical activity over the prior year. Symptoms of depression were assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (range, 0–60) (30) at examinations in 1990, 1995, 2005, 2010, and 2015. Because depression was not assessed at each time point, previously published statistical techniques (31) were followed to calculate a time-weighted average of depressive symptoms over the study period to be used in the models.

Analytical sample exclusions

Of the 5,114 CARDIA participants, 1,978 (38.7%) had complete contemporaneous measurements of both income and BMI at all 7 study visits between 1990 and 2015; 2,839 participants (55.5%) had at least 6 complete contemporaneous measurements; and 3,815 participants (74.6%) had at least 4 complete contemporaneous measurements. To be included in the present study, participants had to have at least 1 complete contemporaneous measurement of income and BMI; 4,762 (or 93.1%) participants met this criterion and were included in the analytical sample. Those included versus excluded did not differ significantly with respect to age, sex, BMI, or education but did differ according to race (P < 0.05): 5% of white versus 10% of black participants were excluded in the final analytical sample (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

Differences in baseline characteristics of the study population were assessed overall and according to exposure to poverty (comparing those never vs. ever in poverty over 25 years). Differences in means and proportions in baseline characteristics were tested using t tests and χ2 tests respectively. The distribution of sustained poverty from 1990 to 2015 was illustrated across sex and racial groups.

To examine the longitudinal association, linear mixed-effects growth models with random intercepts were used to estimate the associations between a 10% increase in sustained poverty and BMI growth rate over the 25-year period. By using a random intercept, we allowed initial BMI to vary between individuals. Random slopes were not added to the models; they did not improve model fit. The data structure included year 1990 (baseline) and 6 follow-up time points through 2015. Participants’ BMI was treated as a time-dependent outcome, and thus the model estimated BMI as a function of time. Time was operationalized as calendar years of the study (from 1990 to 2015), and the regression coefficient for year was interpreted as BMI rate of change per year.

To determine the association between sustained poverty and BMI growth, a sustained poverty × time interaction term was included in all models. A quadratic term for time (year2), which measured whether BMI growth leveled off over time, and a sustained poverty × quadratic time interaction term were tested and retained in the models if significant. A 4-way interaction between sustained poverty, time, sex, and race was tested in a model that included all lower-level interactions, to determine whether the relationship between sustained poverty and BMI growth varied according to sex and race. The interaction was significant (P = 0.03), and thus all subsequent models were stratified by sex and race. Crude models (model 1) were presented along with models adjusting for sociodemographic confounders (model 2), including baseline age, education, parental education, time-dependent marital status, and study site. We also considered a third model, additionally adjusting for behavioral characteristics including smoking, depressive symptoms, and physical activity, which we hypothesized were confounders and potentially partial mediators (i.e., poverty may influence smoking status, depressive symptoms, or physical activity—all 3 of which may influence changes in BMI). Using the fully adjusted estimates (model 3), we illustrated the 25-year trajectories of BMI across different levels of sustained poverty (never in poverty or 0%, in poverty 50% of visits, and always in poverty or 100%).

To address the possibility of reverse causation (i.e., that obesity results in loss of income and consequently poverty), we repeated the multivariable analysis in a sample restricted to those not overweight or obese at baseline. To do that, we excluded 2,072 people who in 1990 had a BMI ≥25. The rationale was that participants who were not overweight or obese at baseline (i.e., those retained in the restricted sample) were less likely to experience social drift, and thus any observed positive association between poverty and BMI in the restricted sample of 2,690 participants would be less likely due to reverse causation. Reverse causation would imply that any positive association observed in the full sample would become null or attenuated in the restricted sample. All analyses were performed with R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Significance testing was 2-sided at an α of 0.05 and 0.10 for interactions.

RESULTS

Mean age at baseline in 1990 was 30.0 years old, 54.9% were women, and 50.6% were black (Table 1). Those in poverty at least once between years 1990 and 2015 were more likely to be women, black, have lower mean years of education, and lower mean parental education compared with those never in poverty. Compared with individuals never in poverty, those in poverty at least once were less physically active and had a higher number of depressive symptoms at baseline.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample at Baseline, Overall and According to Poverty Status, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults, United States, 1990

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 4,762) | Poverty Status Between 1990–2015 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never in Poverty (n = 2,377) | In Poverty at Least Once (n = 2,385) | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | No. | % | Mean (SD) | No. | % | Mean (SD) | No. | % | |

| Age, yearsa | 30.0 (3.6) | 30.5 (3.3) | 29.3 (3.8) | ||||||

| Femaleb | 2,612 | 54.9 | 1,245 | 52.4 | 1,367 | 57.3 | |||

| Blackb | 2,408 | 50.6 | 851 | 35.8 | 1,557 | 65.3 | |||

| Education, yearsa | 14.4 (2.4) | 15.3 (2.3) | 13.4 (2.2) | ||||||

| Parental education, yearsa | 13.8 (3.1) | 14.4 (3.1) | 13.2 (3.0) | ||||||

| Marriedb | 1,743 | 36.6 | 1,110 | 46.7 | 633 | 26.5 | |||

| 1990 income, $a | $34,665 (21,769) | $47,396 (18,339) | $21,791 (16,835) | ||||||

| Smoking statusb | |||||||||

| Never | 2,482 | 52.1 | 1,377 | 57.9 | 1,105 | 46.3 | |||

| Current | 609 | 12.8 | 369 | 15.5 | 240 | 10.1 | |||

| Former | 1,240 | 26 | 422 | 17.8 | 818 | 34.3 | |||

| Physical activity, exercise unitsa | 379.7 (292.6) | 406.6 (293) | 352.5 (289.7) | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | |||||||||

| CES-D scorea | 11.2 (8.1) | 9.4 (7.1) | 13.1 (8.7) | ||||||

| CES-D score ≥16b | 1,042 | 21.9 | 363 | 15.3 | 679 | 28.5 | |||

Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; SD, standard deviation.

a Means differed across poverty groups using t tests (P < 0.01).

b Proportions differed across poverty groups using χ2 tests (P < 0.01).

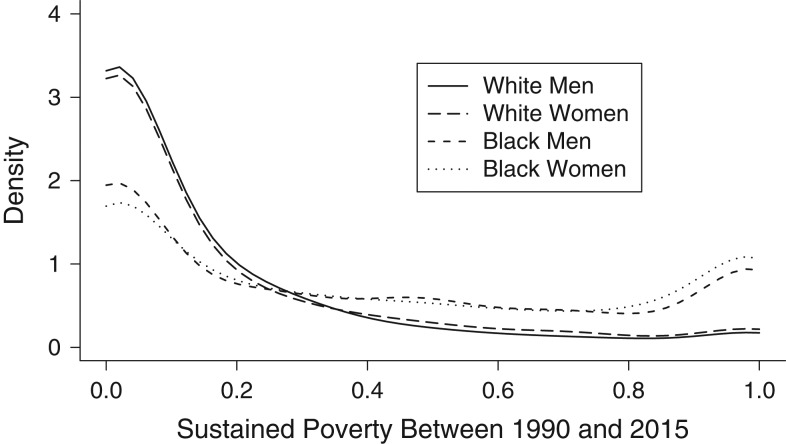

The distribution of sustained poverty (i.e., proportion of visits in poverty) between years 1990 and 2015 is displayed in Figure 1, according to sex and race. Black participants (men and women) were more likely to always be in poverty (i.e., sustained poverty of 1) and less likely to have never been in poverty (i.e., sustained poverty of 0) compared with white participants.

Figure 1.

Distribution of sustained poverty across sex and racial groups, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, United States, 1990–2015. This density function represents the probability of having a specific value of sustained poverty, which is determined by both the height and width of each data point. Thus, height can exceed 1 with a narrow width. Sustained poverty values of “0.0” indicate never in poverty over the 25-year study period (i.e., between 1990 and 2015), and “1.0” indicates always in poverty.

At baseline in 1990, being in poverty versus not was not cross-sectionally associated with BMI among white men (25.7 vs. 25.6; P = 0.68) but was associated with lower mean BMI among black men (25.9 vs. 26.8; P < 0.01) and with higher mean BMI among white women (25.4 vs. 24.1; P < 0.01). There was no cross-sectional association among black women (28.5 vs. 27.9; P = 0.19) (data not shown).

Among white men (Table 2, model 3), fully adjusted results from linear mixed-effects models showed that BMI increased each year, with a positive linear term of 0.23 units per year (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.20, 0.26; P < 0.01). The quadratic term was significant but negative, indicating slowing of BMI growth (−0.004, 95% CI: −0.005, −0.002; P < 0.01). A 10% increase in sustained poverty was associated with faster BMI growth (0.004, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.008; P = 0.01). For example, a white man always versus never in poverty from 1990 to 2015 was predicted to have an additional BMI increase of 1.00 unit. Estimates from the sample restricted to those not overweight or obese at baseline were less precise but comparable to those from the full sample.

Table 2.

Multivariable Associations Between 10% Increase in Time-Dependent Sustained Poverty and Body Mass Index Growth Among Men, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults, United States, 1990–2015

| Characteristic | White Men | Black Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All White Men (n = 1,108) | White Men With Baseline BMIa <25 (n = 606) | All Black Men (n = 1,042) | Black Men With Baseline BMIa <25 (n = 550) | |||||

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |

| Model 1b | ||||||||

| Intercept | 25.57c | 25.28, 25.86 | 22.95c | 22.67, 23.22 | 26.61c | 26.22, 27.01 | 23.53c | 23.11, 23.95 |

| Poverty | 0.006 | −0.040, 0.053 | −0.005 | −0.060, 0.049 | −0.050e | −0.091, −0.010 | −0.029 | −0.077, 0.019 |

| Year | 0.24c | 0.22, 0.27 | 0.26c | 0.22, 0.29 | 0.32c | 0.29, 0.35 | 0.30c | 0.27, 0.34 |

| Poverty × year | 0.006c | 0.003, 0.009 | 0.007c | 0.003, 0.012 | −0.007c | −0.009, −0.005 | −0.006c | −0.009, −0.004 |

| Year2 | −0.004c | −0.005, −0.003 | −0.005c | −0.006, −0.003 | −0.005c | −0.007, −0.004 | −0.005c | −0.006, −0.003 |

| Model 2d | ||||||||

| Intercept | 25.21c | 24.59, 25.83 | 22.82c | 22.35, 23.29 | 27.32c | 26.61, 28.03 | 23.41c | 22.89, 23.92 |

| Poverty | −0.019 | −0.069, 0.031 | −0.033 | −0.089, 0.023 | −0.048e | −0.093, −0.002 | −0.028 | −0.079, 0.022 |

| Year | 0.24c | 0.21, 0.26 | 0.25c | 0.21, 0.29 | 0.33c | 0.29, 0.36 | 0.30c | 0.26, 0.35 |

| Poverty × year | 0.007c | 0.003, 0.010 | 0.007c | 0.003, 0.012 | −0.007c | −0.010, −0.005 | −0.006c | −0.009, −0.003 |

| Year2 | −0.004c | −0.005, −0.003 | −0.005c | −0.006, −0.003 | −0.006c | −0.007, −0.005 | −0.005c | −0.007, −0.003 |

| Model 3f | ||||||||

| Intercept | 25.21c | 24.25, 26.17 | 23.44c | 22.47, 24.42 | 28.29c | 27.05, 29.53 | 23.85c | 22.69, 25.01 |

| Poverty | −0.033 | −0.084, 0.018 | −0.029 | −0.088, 0.029 | −0.043 | −0.090, 0.004 | −0.015 | −0.069, 0.039 |

| Year | 0.23c | 0.20, 0.26 | 0.25c | 0.21, 0.30 | 0.33c | 0.29, 0.36 | 0.30c | 0.25, 0.34 |

| Poverty × year | 0.004e | 0.001, 0.008 | 0.005e | 0.000, 0.010 | −0.008c | −0.010, −0.005 | −0.006c | −0.009, −0.002 |

| Year2 | −0.004c | −0.005, −0.002 | −0.005c | −0.007, −0.003 | −0.006c | −0.007, −0.004 | −0.005c | −0.007, −0.003 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

a Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

b Models were centered on age, education, and parental education. Model 1 is crude.

cP < 0.01.

d Model 2 adjusted for baseline age, baseline education, time-dependent marital status, highest level of parental education, and study site.

eP < 0.05.

f Model 3 additionally adjusted for time-dependent smoking status and physical activity (exercise units) and time-weighted average of depressive symptoms.

Among black men (Table 2, model 3), fully adjusted results from linear mixed-effects models showed that BMI increased each year, with a positive linear term of 0.33 units per year (95% CI: 0.29, 0.36; P < 0.01). The quadratic term was negative, indicating a slowing of BMI growth (−0.006, 95% CI: −0.007, −0.004; P < 0.01). A 10% increase in sustained poverty was associated with a slower BMI growth (−0.008, 95% CI: −0.010, −0.005; P < 0.01). For example, a black man always versus never in poverty from 1990 to 2015 was predicted to have 2-unit lower BMI growth. Estimates from the sample restricted to those not overweight or obese at baseline were comparable to those from the full sample.

Among white women (Table 3, model 3), fully adjusted results from linear mixed-effects models showed that BMI increased each year, with a positive linear term of 0.26 units per year (95% CI: 0.23, 0.29; P < 0.01). The quadratic term was negative, indicating a slowing of BMI growth (−0.004, 95% CI: −0.005, −0.002; P < 0.01). A 10% increase in sustained poverty was associated with faster BMI growth (0.003, 95% CI: 0.000, 0.006; P = 0.07). For example, a white woman always versus never in poverty from 1990 to 2015 was predicted to have an additional BMI increase of 0.75 units. In the analysis restricted to those not overweight or obese at baseline, the association between sustained poverty and faster BMI growth was strengthened.

Table 3.

Multivariable Associations Between 10% Increase in Time-Dependent Sustained Poverty and Body Mass Index Growth Among Women, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults, United States, 1990–2015

| Characteristic | White Women | Black Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All White Women (n = 1,246) | White Women With Baseline BMIa <25 (n = 881) | All Black Women (n = 1,366) | Black Women With Baseline BMIa <25 (n = 653) | |||||

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |

| Model 1b | ||||||||

| Intercept | 24.13c | 23.77, 24.49 | 21.84c | 21.58, 22.10 | 28.21c | 27.74, 28.68 | 23.30c | 22.81, 23.79 |

| Poverty | 0.109c | 0.060, 0.158 | 0.040 | −0.003, 0.083 | −0.007 | −0.052, 0.039 | 0.010 | −0.042, 0.061 |

| Year | 0.28c | 0.26, 0.31 | 0.21c | 0.19, 0.23 | 0.42c | 0.39, 0.45 | 0.40c | 0.36, 0.44 |

| Poverty × year | 0.004c | 0.001, 0.007 | 0.004c | 0.002, 0.007 | −0.002 | −0.004, 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.002, 0.003 |

| Year2 | −0.004c | −0.005, −0.003 | −0.002c | −0.003, −0.002 | −0.008c | −0.009, −0.007 | −0.006c | −0.008, −0.005 |

| Model 2d | ||||||||

| Intercept | 24.78c | 24.07, 25.49 | 22.20c | 21.75, 22.66 | 28.45c | 27.68, 29.22 | 22.38c | 21.80, 22.96 |

| Poverty | 0.102c | 0.051, 0.153 | 0.017 | −0.027, 0.061 | 0.012 | −0.039, 0.062 | −0.006 | −0.059, 0.046 |

| Year | 0.28c | 0.25, 0.30 | 0.20c | 0.18, 0.22 | 0.41c | 0.37, 0.44 | 0.36c | 0.32, 0.40 |

| Poverty × year | 0.003e | 0.000, 0.006 | 0.003e | 0.000, 0.006 | −0.001 | −0.003, 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.001, 0.004 |

| Year2 | −0.004c | −0.005, −0.003 | −0.002c | −0.003, −0.001 | −0.007c | −0.009, −0.006 | −0.005c | −0.006, −0.003 |

| Model 3f | ||||||||

| Intercept | 23.99c | 22.96, 25.02 | 22.41c | 21.70, 23.12 | 28.80c | 27.52, 30.09 | 23.47c | 22.33, 24.61 |

| Poverty | 0.103c | 0.051, 0.154 | 0.019 | −0.024, 0.063 | 0.004 | −0.047, 0.054 | 0.002 | −0.052, 0.056 |

| Year | 0.26c | 0.23, 0.29 | 0.19c | 0.16, 0.21 | 0.43c | 0.39, 0.47 | 0.39c | 0.35, 0.43 |

| Poverty × year | 0.003g | 0.000, 0.006 | 0.004e | 0.001, 0.007 | −0.003e | −0.006, 0.000 | −0.001 | −0.004, 0.002 |

| Year2 | −0.004c | −0.005, −0.002 | −0.001c | −0.002, 0.000 | −0.009c | −0.010, −0.007 | −0.006c | −0.008, −0.005 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

a Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

b Models were centered on age, education, and parental education. Model 1 is crude.

cP < 0.01.

d Model 2 adjusted for baseline age, baseline education, time-dependent marital status, highest level of parental education, and study site.

eP < 0.05.

f Model 3 additionally adjusted for time-dependent smoking status and physical activity (exercise units) and time-weighted average of depressive symptoms.

gP < 0.10 (significant for interactions).

Among black women (Table 3, model 3), fully adjusted results from linear mixed-effects models showed that BMI increased each year, with a positive linear term of 0.43 units per year (95% CI: 0.39, 0.47; P < 0.01). The quadratic term was negative, indicating a slowing of BMI growth (−0.009, 95% CI: −0.010, −0.007; P < 0.01). A 10% increase in sustained poverty was associated with slower BMI growth (−0.003, 95% CI: −0.006, 0.000; P = 0.03). For example, a black woman always versus never in poverty from 1990 to 2015 was predicted to have 0.75-unit lower BMI growth. In the analysis restricted to those not overweight or obese at baseline, sustained poverty was no longer associated with BMI growth.

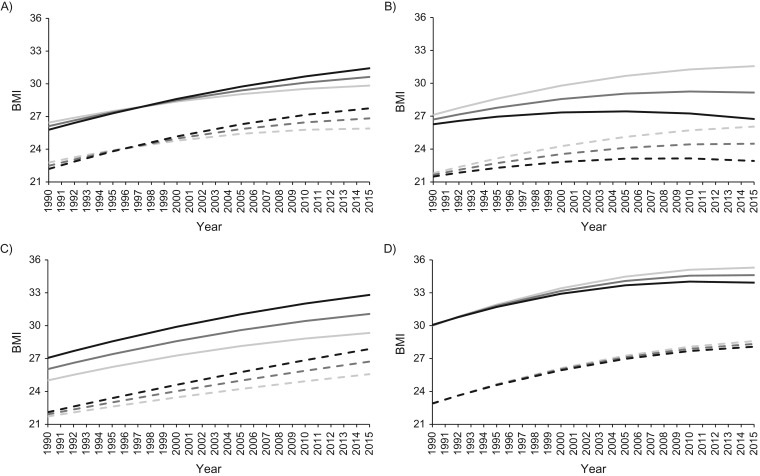

Figure 2 displays BMI trajectories from 1990 to 2015 at various levels of sustained poverty (never in poverty, in poverty at 50% of visits, and always in poverty). Trajectories are based on the fully adjusted results from model 3 shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Predicted trajectories of body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2) between 1990 and 2015 according levels of sustained poverty, in the full sample and the restricted sample, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, United States, 1990–2015. Estimates are based on the fully adjusted results of linear mixed-effect growth models of time-dependent sustained poverty and time-dependent BMI (model 3, Tables 2 and 3). Models adjusted for age, education, marital status, highest level of parental education, study site, smoking status, physical activity exercise units, and Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) score. Predicted BMI trajectories are shown at the following levels of time-dependent sustained poverty: never in poverty, in poverty 50% of visits, and always in poverty. Other covariates used in the models were set to the following levels: age 40 years, 14.88 years of education, 13.8 years of parental education, 25% likelihood of being at each study site, a 47% likelihood of being married, 60% never smokers, 18% current smokers, 22% never smokers, with an average of 347 exercise units and a time-weighted average CES-D score of 11. Light gray lines represent “never in poverty,” medium gray lines represent “in poverty 50% of visits,” and black lines represent “always in poverty.” Solid lines pertain to the full sample, while dashed lines pertain to the restricted sample (BMI <25) in 1990.

DISCUSSION

In our study, between 1990 and 2015, BMI increased in a curvilinear fashion in all sex-racial groups. Our longitudinal findings showed that the association of sustained poverty with BMI growth varied across sex and race. Greater sustained poverty was associated with faster BMI growth among white men and women (an additional 0.75 and 1.00 BMI units gained over 25 years for those always in poverty vs. never in poverty, respectively) and with slower BMI growth among black men and women (2.0 and 0.75 less BMI units gained over 25 years for those always in poverty vs. never in poverty, respectively). We found little evidence of reverse causation—our main findings were mostly comparable in the sample restricted to those not overweight or obese at baseline. Taken together, our findings suggested that sustained poverty was a modest predictor of changes in BMI over the recent 2 decades in young to middle-aged adults. Additionally, the differential association across race and sex highlights that a uniform, one-size-fits-all approach in describing the associations between poverty/low income and obesity may fail to accurately characterize this nuanced association.

Similar to other studies (5, 13), among white men we found that poverty was not associated with BMI cross-sectionally, although we did find a positive, albeit weak, longitudinal association. Results from repeated National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) assessments during 1971–2002 showed a gradient between income and BMI among white men, which was positive at lower income levels and, similar to our findings, was slightly inverse at higher incomes of more recent NHANES waves (32). Our results showing only modest positive associations between poverty and BMI growth during a recent time frame are in line with these prior findings as well as results from NHANES 2005–2008 showing no clear cross-sectional poverty-to-BMI pattern among white men (5). Among black men, the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations were also consistent with prior research showing an inverse association between poverty and BMI (i.e., protective) (5, 13, 32) and, more specifically, that black men at higher versus lower income distributions experience larger gains in BMI (32). Perhaps most notable, and previously documented from cross-sectional NHANES studies (5), is the clear differential association between poverty and BMI among men according to race. It has been hypothesized that men in poverty are more likely to engage in occupations that are physically demanding and energy consuming (32), which could help explain the findings among black men. Further, food insecurity has been shown to be more common among poor blacks versus poor whites (33), offering a potential mechanistic explanation of the inverse association among black but not white men. However, further research is certainly warranted to corroborate our results and determine underlying pathways that can explain the differential associations.

Women, on the other hand, have been shown to be more susceptible to the obesogenic force of poverty than men (34). In a repeated cross-sectional study of Finnish adults aged 25–64 years, high income was associated with lower BMI among women (35). Similarly, data from NHANES showed strong inverse associations between income and BMI among white women at all examination periods (32). Consistent with prior literature, our findings, which used repeated income and BMI measurements, showed an inverse association between poverty and BMI. It is suggested that among white women, poverty and obesity may be mutually reinforcing due to the stigma that often accompanies being overweight or obese (24, 36, 37). In fact, white women experience income penalties for just being mildly overweight (26, 36), and overweight/obese white women report more weight-based discrimination than do overweight/obese black women or men (38). However, we found no evidence of reverse causation among white women; our main findings were strengthened in analyses restricted to those not overweight or obese at baseline.

Among black women, the association between income, or other indicators of socioeconomic status, and obesity has been less consistent than among white women (5, 32, 39). Findings from NHANES have shown that among black women, lower income was associated with slower BMI growth (32). Yet, findings from other studies (15, 39), such as the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation showed no associations among black women. Our results were consistent with both studies; sustained poverty was associated with slower BMI growth, a result that became null once the sample was restricted to those not obese at baseline. Similar to the results among men, directionality of the associations between white and black women also differed. It has been hypothesized that such race differences may be attributed in part to differences in standards of ideal body image (32). For example, compared with black women, white women report more stigma related to being overweight or obese (40, 41). However, whether white women are more likely to deploy socioeconomic resources to prevent weight gain remains speculative and warrants further investigation.

Pathways traditionally cited as underlying the relationship between poverty and health include low income being associated with unhealthy behaviors (42–44), limited access to resources (45), inadequate living environments (such as limited access to recreational facilities (43) and limited access to high quality foods (46–49)), and greater exposure to stress-inducing mechanisms (50–53). However, such general pathways cannot explain the inverse association found among black participants and call for more a more nuanced approach. Furthermore, while BMI often increases with age, the steep and substantial BMI growth experienced by all sex and racial groups over the 25-year period may also be a reflection of the obesity epidemic, although the present analysis could not distinguish between these age and period effects. Likewise, we could not determine whether the quadratic trend, indicative of a slowdown in the obesity growth rate (a finding described in other studies (54, 55)), reflects a natural BMI trajectory ceiling effect or is the consequence of public health initiatives such as obesity reduction initiatives (56). However, recent findings from NHANES show that the prevalence of obesity has increased continuously among women without a slowdown (4), warranting further investigation of BMI and obesity trends over time.

This study has some additional limitations that are worth noting. Despite our cohort being relatively young, BMI differences according to baseline poverty status were already established, and mean BMI was already high, especially among black women. Thus, the extent of BMI growth could not be fully captured. Additionally, income was recorded as a range rather than actual income, although this would likely result in a nondifferential bias if any. Finally, while time was operationalized as calendar years, we acknowledge that calendar years may not coincide exactly with the date of each participant’s assessment and anticipate that some assessments may have occurred earlier while others occurred later. However, it is unlikely that there were any systematic differences in the timing of the assessments versus calendar years.

Despite such limitations, this study has several strengths. The prospective design of our study with the clear temporality between BMI and income allowed us to more accurately characterize their longitudinal relationship, and thus it builds upon previous literature that is primarily cross-sectional. Additionally, our findings rely on repeated measurements of income and BMI over 25 years going from young adulthood into midlife, which allowed us to uniquely characterize exposure to poverty as a cumulative time-updated measure. The biracial nature of the cohort also allowed us to examine the associations across racial and sex groups. Finally, our results were robust to analyses aimed at ruling out reverse causation/social drift as a sole explanation—although we acknowledge that BMI is not naturally a dichotomous construct and thus nonoverweight or nonobese individuals may have still experienced weight-related discrimination that may have influenced their income, which we could not account for in this analysis.

In conclusion, between 1990 and 2015, increased sustained poverty was associated with faster BMI growth among white men and women and with slower BMI growth among black men and women, results that could not be explained entirely by reverse causation (i.e., higher BMI resulting in low income). Although modest, these results do provide further evidence supporting a link between poverty and changes in BMI. Additionally, the present findings emphasize stark differences in both directionality and size of association by sex and race. Such results underscore a need for more research aimed at elucidating the mechanisms underlying the complex relationships between poverty and BMI across different race and sex groups.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Division of Epidemiology, Department of Public Health Sciences, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, Florida (Tali Elfassy, Adina Zeki Al Hazzouri); Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California (M. Maria Glymour); Department of Preventive Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois (Kiarri N. Kershaw, Mercedes Carnethon); Department of Psychology, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida (Maria M. Llabre, Neil Schneiderman); and Division of Preventive Medicine, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama (Cora E. Lewis).

T.E. was supported by the American Heart Association (grant 17POST32490000) and by the National Institutes of Health (grant HL 007426). A.Z.H. was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (grant K01AG047273). The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contracts HHSN268201300025C, HHSN268201300026C, HHSN268201300027C, HHSN268201300028C, HHSN268201300029C, and HHSN268200900041C), the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, and an agreement between the National Institute on Aging and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (agreement AG0005).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CARDIA

Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults

- CI

confidence interval

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Appendix Table 1.

Description of Income Range and Category Midpoint Among Participants, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults, 1990–2015

| Income Range, $ | Category Midpoint, $ | |

|---|---|---|

| 1990–1995 | 2000–2015 | |

| 0–4,999 | 2,500 | 2,500 |

| 5,000–11,999 | 8,500 | 8,500 |

| 12,000–15,999 | 14,000 | 14,000 |

| 16,000–24,999 | 20,500 | 20,500 |

| 25,000–34,999 | 30,000 | 30,000 |

| 35,000–49,999 | 42,500 | 42,500 |

| 50,000–74,999 | 62,500 | 62,500 |

| ≥75,000a | 75,000 | n/a |

| 75,000–99,999a | n/a | 87,500 |

| ≥100,000a | n/a | 100,000 |

a In 2000, changes in the income groups were made to accommodate higher incomes. Income categories for incomes under $75,000 were constant for all study years.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(21):1925–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61(4):1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hammond RA, Levine R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2010;3:285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. . Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ogden CL, Lamb MM, Carroll MD, et al. . Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;(50):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harrell JS, Gore SV. Cardiovascular risk factors and socioeconomic status in African American and Caucasian women. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21(4):285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jeffery RW, Forster JL, Folsom AR, et al. . The relationship between social status and body mass index in the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Int J Obes. 1989;13(1):59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin BH, Huang CL, French SA. Factors associated with women’s and children’s body mass indices by income status. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(4):536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manson JE, Lewis CE, Kotchen JM, et al. . Ethnic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle correlates of obesity in US women. Clin J Womens Health. 2001;1(5):225–234. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Winkleby MA, Kraemer HC, Ahn DK, et al. . Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: findings for women from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. JAMA. 1998;280(4):356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wardle J, Waller J, Jarvis MJ. Sex differences in the association of socioeconomic status with obesity. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1299–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Q, Wang Y. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1171–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boykin S, Diez-Roux AV, Carnethon M, et al. . Racial/ethnic heterogeneity in the socioeconomic patterning of CVD risk factors: in the United States: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):111–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Waldstein SR, Moody DLB, McNeely JM, et al. . Cross-sectional relations of race and poverty status to cardiovascular risk factors in the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Lifespan (HANDLS) study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gaston MH, Porter GK, Thomas VG. Paradoxes in obesity with mid-life African American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. James SA, Fowler-Brown A, Raghunathan TE, et al. . Life-course socioeconomic position and obesity in African American Women: the Pitt County Study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):554–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baltrus PT, Lynch JW, Everson-Rose S, et al. . Race/ethnicity, life-course socioeconomic position, and body weight trajectories over 34 years: the Alameda County Study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1595–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu H, Guo G. Lifetime socioeconomic status, historical context, and genetic inheritance in shaping body mass in middle and late adulthood. Am Sociol Rev. 2015;80(4):705–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coogan PE, Wise LA, Cozier YC, et al. . Lifecourse educational status in relation to weight gain in African American women. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(2):198–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scharoun-Lee M, Kaufman JS, Popkin BM, et al. . Obesity, race/ethnicity and life course socioeconomic status across the transition from adolescence to adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(2):133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pudrovska T, Logan ES, Richman A. Early-life social origins of later-life body weight: the role of socioeconomic status and health behaviors over the life course. Soc Sci Res. 2014;46:59–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duncan GJ. Income dynamics and health. Int J Health Serv. 1996;26(3):419–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Federal Reserve Board The Evolution of Household Income Volatility. Washington, DC: Division of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board; 2007. (Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2007-61) [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pudrovska T, Reither EN, Logan ES, et al. . Gender and reinforcing associations between socioeconomic disadvantage and body mass over the life course. J Health Soc Behav. 2014;55(3):283–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Warren JR. Socioeconomic status and health across the life course: a test of the social causation and health selection hypotheses. Soc Forces. 2009;87(4):2125–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maranto CL, Stenoien AF. Weight discrimination: a multidisciplinary analysis. Empl Responsib Rights J. 2000;12:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. . CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. US Census Bureau Poverty thresholds. US Department of Commerce; 2017. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html. Accessed September 22, 2017.

- 29. Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ. Cumulative impact of sustained economic hardship on physical, cognitive, psychological, and social functioning. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(26):1889–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Pletcher MJ, et al. . Early adult to midlife cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive function. Circulation. 2014;129(15):1560–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang VW, Lauderdale DS. Income disparities in body mass index and obesity in the United States, 1971–2002. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(18):2122–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. United States Department of Agriculture Household Food Security in the United States, 2011. Washington, DC: Economic Research Service; 2012. (Economic Research Report Number 141).

- 34. Wang M, Yi Y, Roebothan B, et al. . Body mass index trajectories among middle-aged and elderly Canadians and associated health outcomes. J Environ Public Health. 2016;2016:7014857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prättälä R, Sippola R, Lahti-Koski M, et al. . Twenty-five year trends in body mass index by education and income in Finland. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Averett S, Korenman S. The economic reality of the beauty myth. J Hum Resour. 1996;31(2):304–330. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khlat M, Jusot F, Ville I. Social origins, early hardship and obesity: a strong association in women, but not in men? Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(9):1692–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dutton GR, Lewis TT, Durant N, et al. . Perceived weight discrimination in the CARDIA study: differences by race, sex, and weight status. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(2):530–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lewis TT, Everson-Rose SA, Sternfeld B, et al. . Race, education, and weight change in a biracial sample of women at midlife. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(5):545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chang VW, Christakis NA. Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(4):332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paeratakul S, White MA, Williamson DA, et al. . Sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and BMI in relation to self-perception of overweight. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT. Why do poor people behave poorly? Variation in adult health behaviours and psychosocial characteristics by stages of the socioeconomic lifecourse. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(6):809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Evenson KR, et al. . Availability of recreational resources in minority and low socioeconomic status areas. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(1):16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang S, Lynch JW, Raghunathan TE, et al. . Socioeconomic and psychosocial exposures across the life course and binge drinking in adulthood: population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(2):184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(2):60–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lake A, Townshend T. Obesogenic environments: exploring the built and food environments. J R Soc Promot Health. 2006;126(6):262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, et al. . Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(1):23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rundle A, Diez Roux AV, Free LM, et al. . The urban built environment and obesity in New York City: a multilevel analysis. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21(4 suppl):326–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rundle A, Neckerman KM, Freeman L, et al. . Neighborhood food environment and walkability predict obesity in New York City. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(3):442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brunner E. Stress and the biology of inequality. BMJ. 1997;314(7092):1472–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(1 Pt 2):215–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lynch J, Smith GD, Harper S, et al. . Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Milbank Q. 2004;82(1):5–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moore CJ, Cunningham SA. Social position, psychological stress, and obesity: a systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(4):518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. . Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. . Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Essington M, Hertelendy AJ. Legislating weight loss: are antiobesity public health policies making an impact? J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41(3):453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]