Abstract

During development, neuronal cells extend an axon toward their target destination in response to a cue to form a properly functioning nervous system. Rho proteins, Ras-related small GTPases that regulate cytoskeletal organization and dynamics, cell adhesion, and motility, are known to regulate axon guidance. Despite extensive knowledge about canonical Rho proteins (RhoA/Rac1/Cdc42), little is known about the Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) atypical Cdc42-like family members CHW-1 and CRP-1 in regards to axon pathfinding and neuronal migration. chw-1(Chp/Wrch) encodes a protein that resembles human Chp (Wrch-2/RhoV) and Wrch-1 (RhoU), and crp-1 encodes for a protein that resembles TC10 and TCL. Here, we show that chw-1 works redundantly with crp-1 and cdc-42 in axon guidance. Furthermore, proper levels of chw-1 expression and activity are required for proper axon guidance. When examining CHW-1 GTPase mutants, we found that the native CHW-1 protein is likely partially activated, and mutations at a conserved residue (position 12 using Ras numbering, position 18 in CHW-1) alter axon guidance and neural migration. Additionally, we showed that chw-1 genetically interacts with the guidance receptor sax-3 in PDE neurons. Finally, in VD/DD motor neurons, chw-1 works downstream of sax-3 to control axon guidance. In summary, this is the first study implicating the atypical Rho GTPases chw-1 and crp-1 in axon guidance. Furthermore, this is the first evidence of genetic interaction between chw-1 and the guidance receptor sax-3. These data suggest that chw-1 is likely acting downstream and/or in parallel to sax-3 in axon guidance.

Keywords: CHW-1, SAX-3/Robo, axon pathfinding, CRP-1, CDC-42

During proper development of the nervous system, neurons must first migrate to their final position where they then extend axons in order to establish synaptic connections. In order to first migrate and then extend an axon, the neuronal cells must undergo dynamic changes in their actin cytoskeleton organization (Tessier-Lavigne and Goodman 1996); (Dickson 2002; Gallo and Letourneau 2002). Many studies have shown that Rho proteins are required for actin cytoskeleton rearrangement and subsequent neuronal migration and axon extension (Lundquist 2003; Luo 2000; Dickson 2001). Rho family proteins are Ras-related small GTPases that regulate cytoskeletal organization and dynamics, cell adhesion, motility, trafficking, proliferation, and survival (Etienne-Manneville and Hall 2002). Misregulation of Rho proteins can result in defects in cell proliferation, cell adhesion, cell morphology, and cell migration (Ridley 2004). These proteins function as tightly regulated molecular switches, cycling between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state (Jaffe and Hall 2005).

Despite extensive knowledge about regulation and function of the canonical Rho proteins (RhoA/Rac1/Cdc42), little is known about the contribution of the Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) atypical Cdc42-like family members CHW-1 and CRP-1 to axon pathfinding and neuronal migration. C. elegans contains a single gene, chw-1 which encodes a protein that resembles human Chp (Wrch-2/RhoV) and Wrch-1 (RhoU), and crp-1 encodes for a protein that resembles TC10 and TCL.

While chw-1 has not been studied in the context of axon pathfinding, it has been implicated in cell polarity, working with LIN-18/Ryk and LIN-17/Frizzled(Kidd et al. 2015). Additionally, there is a body of literature concerning the related mammalian homologs Wrch-1 (Wnt-regulated Cdc42 homolog-1, RhoU) and Chp (Wrch-2/RhoV), the most recently identified Rho family members. Wrch-1 and Chp share 57% and 52% sequence identity with Cdc42, respectively, and 61% sequence identity with each other (Tao et al. 2001; Aronheim et al. 1998). Wrch-1 and Chp are considered atypical GTPases for a number of reasons. Atypical Rho proteins vary in either their regulation of GTP/GDP-binding, the presence of other domains besides the canonical Rho insert domain, and variances in their N- and C-termini and/or posttranslational modifications. When compared to the other members of the Cdc42 family, Wrch-1 has elongated N-terminal and C-terminal extensions. The N-terminus of Wrch-1 has been shown to be an auto-inhibitory domain, and removal of the N-terminus increases the biological activity of the protein (Shutes et al. 2004; Shutes et al. 2006; Berzat et al. 2005). The N-termini of both Wrch-1 and Chp contain PxxP motifs, which may mediate interactions with proteins containing SH3 domains, such as the adaptor proteins Grb2 and Nck (Zhang et al. 2011). Wrch-1 is also divergent in the C-terminus, when compared to other members of the Cdc42 family. Like Chp (Chenette et al. 2006), instead of being irreversibly prenylated on a CAAX motif, Wrch-1 is reversibly palmitoylated on a CFV motif (Berzat et al. 2005). This reversible modification may lead to more dynamic regulation of the protein.

Although Wrch-1 shares sequence identity with Cdc42 and Chp-1, Wrch-1 shares only partially overlapping localization and effector interactions with these proteins, and its activity is regulated in a distinct manner. Like Cdc42, Wrch-1 activity leads to activation of PAK1 and JNK (Chuang et al. 2007; Tao et al. 2001), formation of filopodia (Ruusala and Aspenstrom 2008; Saras et al. 2004), and both morphological (Brady et al. 2009) and growth transformation in multiple cell types (Berzat et al. 2005; Brady et al. 2009). In addition, Wrch-1 also regulates focal adhesion turnover (Chuang et al. 2007; Ory et al. 2007), negatively regulates the kinetics of tight junction formation (Brady et al. 2009), plays a required role in epithelial morphogenesis (Brady et al. 2009), modulates osteoclastogenesis (Brazier et al. 2009; Ory et al. 2007; Brazier et al. 2006), and regulates neural crest cell migration (Faure and Fort 2011). Chp/Wrch-2, a protein highly related to Wrch-1, was identified in a screen that was designed to look for proteins that interact with p21-activated kinase (Pak1) (Aronheim et al. 1998). Like Wrch-1, Chp also contains N- and C-terminal extensions when compared to Cdc42 and the N-terminus auto-inhibitory domain (Shutes et al. 2004; Chenette et al. 2005). Also like Wrch-1, active Chp leads to cell transformation (Chenette et al. 2005), signals through PAK (PAK6) (Shepelev and Korobko 2012) and JNK (Shepelev et al. 2011), and is involved in neural crest cell specification and migration (Faure and Fort 2011; Guémar et al. 2007).

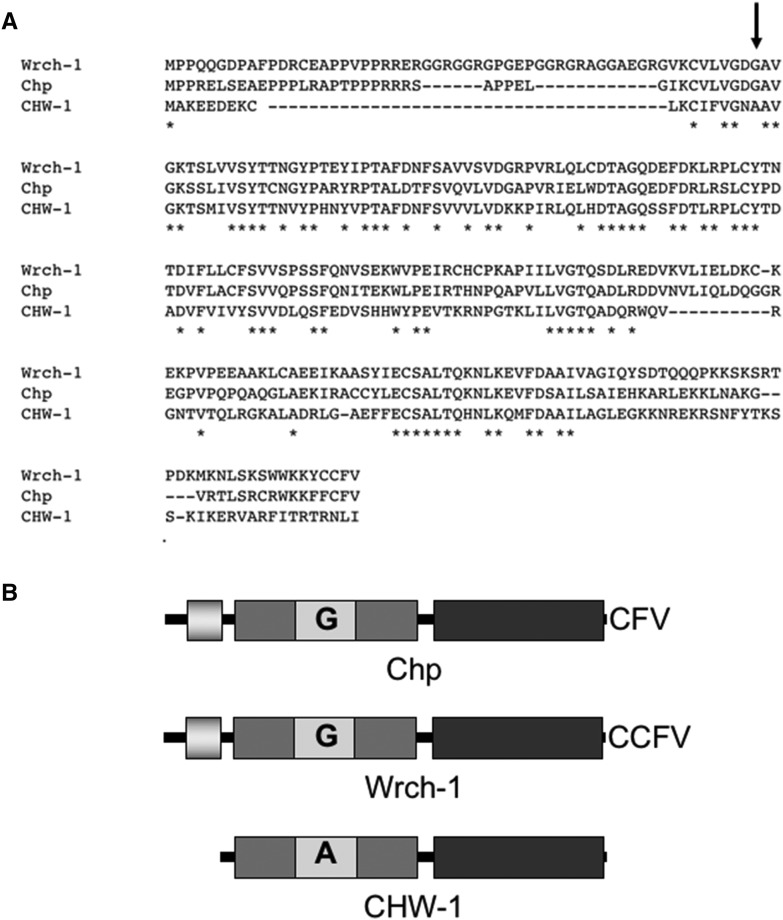

While the GTPase domain of CHW-1 is highly similar to human Wrch-1 and Chp/Wrch-2, it is divergent in its N- and C-terminus. The N-terminal extension found in both Wrch-1 and Chp/Wrch-2, which regulates the function of these proteins, is absent in CHW-1. Additionally, CHW-1 lacks any C-terminal lipid modification motif, such as a CXX motif found in Wrch-1 and Chp/Wrch-1, suggesting that it does not require membrane targeting for its function. While CHW-1 bears some sequence identity to both Wrch-1, Chp/Wrch-1 and Cdc42, it is most similar to human Wrch-1 (Kidd et al. 2015).

The C. elegans protein CRP-1, a member of the Cdc42 subfamily, shares sequence identity, possess atypical enzymatic activity and possesses similar functions to the mammalian GTPases TC10 and TCL (Aspenström et al. 2004; de Toledo et al. 2003; Michaelson et al. 2001; Murphy et al. 2001; Murphy et al. 1999; Jenna et al. 2005; Vignal et al. 2000). Interestingly, like CRP-1, TC10 and TCL localize at internal membranes (Michaelson et al. 2001; Aspenström et al. 2004; Vignal et al. 2000; Jenna et al. 2005). Also, like CRP-1, TC10 and TCL mediate cellular trafficking (Jenna et al. 2005; Okada et al. 2008; de Toledo et al. 2003). However, unlike the rest of the Cdc42 family members, overexpression of CRP-1 was unable to induce cytoskeletal changes in mouse fibroblasts, suggesting that CRP-1 may have overlapping and unique functions compared to other Cdc42 family members (Jenna et al. 2005). Indeed, unlike other Cdc42 family members, crp-1 is an essential component for unfolded protein response-induced transcriptional activities. crp-1 mediates this processes through physical and genetic interactions with the AAA+ ATPase CDC-48 (Caruso et al. 2008).

Because members of the Rho family have many overlapping functions, in addition to their unique functions, we hypothesized that atypical Rho GTPases, like the other Rho family small GTPases, may contribute to axon guidance. To test this hypothesis, we genetically characterized the C. elegans atypical Rho GTPases chw-1 and crp-1, in axon pathfinding. In summary, this is the first study characterizing the role of the C. elegans atypical Rho GTPases in axon guidance. We found that chw-1 is acting redundantly with crp-1 and cdc-42 in axon guidance. Like other Rho GTPases, CHW-1 is involved in axon guidance, and it works redundantly with CRP-1 and CDC-42 in this context. Furthermore, we showed that chw-1 interacts genetically with the guidance receptor sax-3 in axon guidance.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans genetics and transgenics

C. elegans were cultured using standard techniques (Brenner 1974; Wood 1988). All of the experiments were done at 20°, unless otherwise noted. Transgenic worms were made by gonadal micro-injection using standard techniques (Mello and Fire 1995). RNAi was done using clones from the Ahringer library, as previously described (Kamath and Ahringer 2003). The following mutations and constructs were used in this work: LGI- unc-40(n324); LGII- cdc-42(gk388), mIn1; LGV- chw-1(ok697), crp-1(ok685); LGX- sax-3(ky123), unc-6(ev400), LqIs2 (osm-6::gfp); LG unassigned- osm-6::chw-1::gfp, osm-6::chw-1(A18G)::gfp, osm-6::chw-1(A18V)::gfp, unc-25::myr::sax-3.

The mutants were maintained as homozygous stocks, when possible. In some cases, this was not possible because the double mutants were lethal or maternal-lethal, and thus could not be maintained as homozygous stocks. If this was the case, the mutation was maintained in a heterozygous state over a balancer chromosome. cdc-42(gk388) was balanced by mIn1, which harbors a transgene that drives gfp expression in the pharynx. cdc-42(gk388) homozygotes were identified by lack of pharyngeal green fluorescent protein (GFP).

Scoring of PDE and VD/DD axon defects

Axon pathfinding defects were scored in the fourth larval stage (L4) or in young pre-gravid adult animals harboring green fluorescent protein (gfp), which was expressed in specific cell types. In the event that the animals did not survive to this stage, they were counted at an earlier stage with appropriate controls. The PDE neurons and axons were visualized in cells that had an osm-6::gfp transgene (lqIs2 X), which is expressed in all ciliated neurons including the PDE. A PDE axon was considered to be misguided if it failed to extend an axon directly to the ventral nerve cord (VNC). If the trajectory of the axon was greater than a 45° angle from the wild-type position, the axon was scored as misguided, whether it eventually reached the VNC or not. The neurons were considered to have ectopic lamellipodia if they had a lamellipodia-like structure protruding from anywhere on the cell body, axon, or dendrite.

The VD/DD motor neuron morphology was scored in animals that had an unc-25::gfp transgene (juIs76 II) (Jin et al. 1999). The unc-25 promoter is turned on in all GABAergic neurons, including the VDs and DDs. In wild-type animals, the VD/DD commissures extend directly from the VNC toward the dorsal surface of the animals. At the dorsal surface, they form the dorsal nerve cord. Aberrant VD/DD pathfinding was noted when the commissural axons were misguided or terminated prematurely.

Statistics

The results were analyzed using the Fisher’s Exact Test, calculated in Graphpad. The results were considered significant when P < 0.05. The error bars were calculated using the standard proportion of the mean.

Molecular biology

The CHW-1 constructs were subcloned from cDNA in a pBS (bluescript) vector backbone, which were a generous gift from Dr. Ambrose Kidd, who made these constructs while in the laboratories of Dr. Adrienne Cox and Dr. Channing Der (UNC-Chapel Hill) in collaboration with Dr. Dave Reiner (Texas A&M). The sax-3 cytoplasmic domain (with introns, sequence available upon request) was inserted into an NheI site downstream of and in frame with the myristoylation sequence from human Src (MGSSKS), as previously described (Gitai et al., 2003, Norris and Lundquist 2011, and Norris et al. 2014). This construct was inserted into a vector with a osm-6 promotor and a vector with an unc-25 promotor. The sax-3 sequence was tagged with GFP on the C-terminus.

Recombinant DNA, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and other molecular biology techniques were preformed using standard procedures (Sambrook J. 1989). All primer sequences used in the PCR reactions are available upon request.

Microscopy and imaging

The animals used for the imaging analyses were mounted for microscopy in a drop of M9 buffer on an agarose pad (Wood 1988). Both the buffer and the agarose pad contained 5 mM sodium azide, which was used as an anesthetic. Then, a coverslip was placed over the sample, and the slides were analyzed by epifluorescence for GFP. A Leica DMRE microscope with a Qimaging Rolera MGi EMCCD camera was used, along with Metamorph and ImageJ software.

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article. Strains are available upon request.

Results

chw-1 acts redundantly with cdc-42 and crp-1 in axon guidance

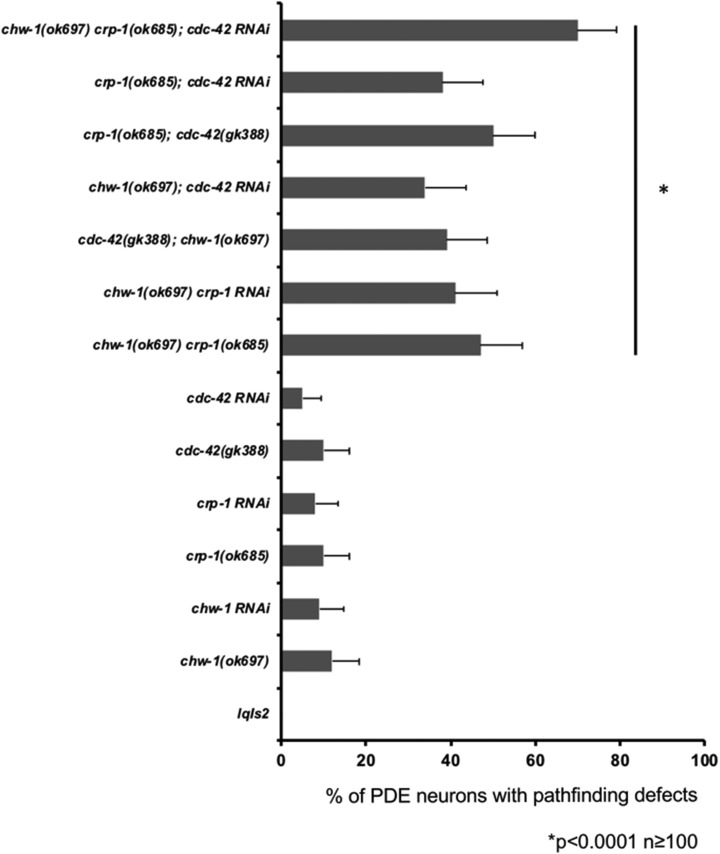

As previously described (Kidd et al. 2015), the C. elegans genome contains a single gene, F22E12.1, which encodes CHW-1, the C. elegans ortholog of human Chp/Wrch-1. The core effector domain of CHW-1 is most similar to human Wrch-1, and is considerably variant from human Chp. The N- and C-termini are significantly different than either human ortholog. While both Wrch-1 and Chp have an N-terminal extension that negatively regulates the protein, this domain is almost entirely absent in CHW-1 (Figure 1). While most Rho proteins terminate in a CAAX motif that signals for an irreversible prenyl lipid modification, both Wrch-1 and Chp end in a CXX motif and are modified by a reversible palmitate modification, which is required for their membrane localization and biological activity (Berzat et al. 2005; Chenette et al. 2005). However, CHW-1 lacks a CAAX or a CXX motif and presumably does not require membrane targeting for its function (Figure 1). Given these differences, we sought to determine the role of chw-1 in axon guidance. The human orthologs of CHW-1 are in the Cdc42 family of Rho proteins, and in mammalian systems, the Cdc42 family of proteins (Cdc42, Wrch-1, Chp, TC10, and TCL) work in concert to carry out both unique and redundant functions. While CHW-1 is the C. elegans ortholog of Wrch-1 and Chp, CRP-1 closely resembles TC10 and TCL in both sequence and function (Caruso et al. 2008; Jenna et al. 2005). Therefore, we first sought to determine whether chw-1 works redundantly with crp-1 and/or cdc42 in axon guidance. For these assays, we visualized the morphology and position of the PDE axons. C. elegans has two bilateral PDE neurons that are located in the post-deirid ganglia of the animal. In the wild-type N2 strain, PDE neurons extend their axons ventrally in a straight line from the cell body to the ventral nerve cord. When the axon reaches the ventral cord, it then branches and extends toward both the anterior and the posterior. To visualize the neurons, we used a transgene gene (lqIs2; osm-6::gfp) expressed in the PDE neurons. The osm-6 promoter is expressed in all ciliated sensory neurons including the PDE neurons (Collet et al. 1998). We observed that alone, deletion alleles or RNAi against chw-1, crp-1, or cdc-42 produced very few axon guidance defects (Figure 2). However, when two or more of these genes were knocked out by either a deletion allele or RNAi we observed a synergistic increase in axon guidance defects (up to 50%). Furthermore, when all 3 genes were knocked out the axon guidance defects increased to 70%. Taken together, these genetic data suggest that chw-1, crp-1, and cdc-42 act redundantly in PDE axon guidance.

Figure 1.

CHW-1 is similar to Wrch-1/RhoU and Chp/Wrch-2/RhoV. Sequence alignment of CHW-1, human Wrch-1, and human Chp done in biology workbench. Identical residues are marked with an asterisk (*). B) CHW-1 lacks the N-terminal extension found in Wrch-1 and Chp (light gray box). CHW-1 also contains an atypical residue (alanine instead of glycine) at position 18 (analogous to position 12 in Cdc42 and most Rho and Ras family members).

Figure 2.

chw-1 works redundantly with cdc-42 and crp-1 in axon guidance. Quantitation of PDE defects. lqIs2 is the osm-6::gfp control transgene. At least 100 neurons were scored for each genotype. P < 0.0001 as determined by Fisher Exact Analysis (Graphpad). The error bars represent the standard proportion of the mean.

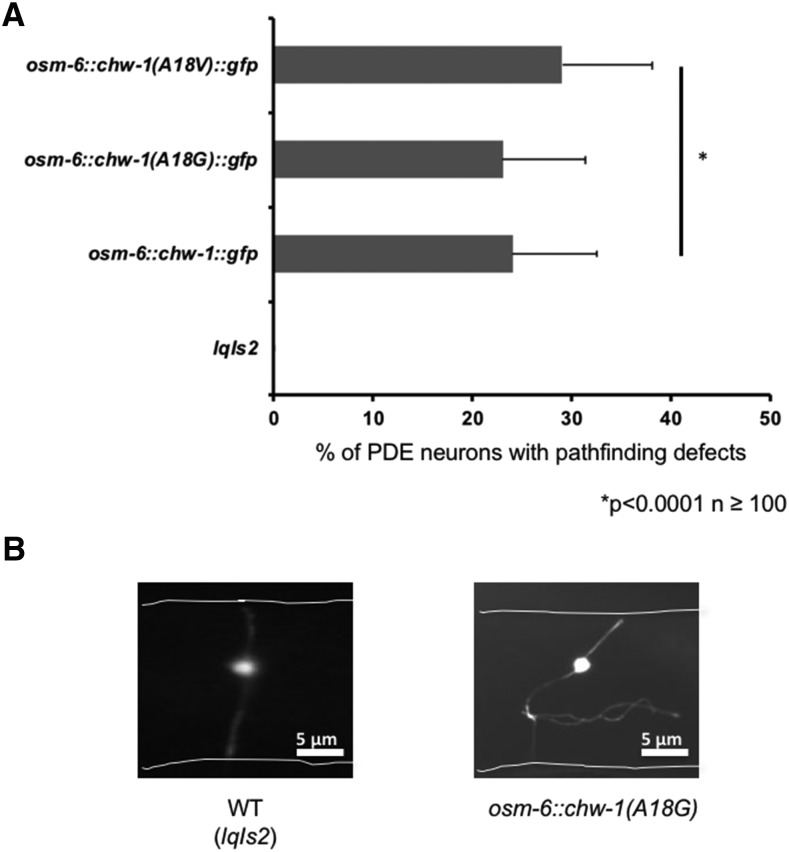

Proper expression and activity levels of CHW-1 are required for axon guidance

Ras superfamily GTPases, including the Rho-family GTPases, cycle between active GTP-bound forms and inactive GDP bound forms driven by the intrinsic GTPase activity of the molecules. The glycine 12 to valine (G12V) substitution has been previously shown to result in inhibition of the intrinsic GTPase activity of the GTPase, favoring the active, GTP-bound state (Wittinghofer et al. 1991). The G12V mutation also makes the protein insensitive to GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) (Ahmadian et al. 1997), rendering the protein constitutively GTP-bound and active. Most Rho proteins harbor a glycine at position 12, however CHW-1 possesses an alanine at this conserved position (position 18 in CHW-1), which is predicted to be a partially activating, resulting in greater GTP-bound levels and an increase in activity. Indeed, evidence from other labs suggests that the native CHW-1 protein may be partially constitutively active (Kidd et al. 2015). We found that transgenic expression of CHW-1, CHW-1(A18V), and CHW-1(A18G) all caused axon guidance defects to a very similar degree (24%, 23%, and 29%, respectively) (Figure 3). This evidence suggests that, like the mammalian counterpart Wrch-1, proper levels of CHW-1 activity are required for correct axon guidance (Alan et al. 2010; Brady et al. 2009). In other words, too much or too little activity of CHW-1 results in an aberrant outcome (misguided axons).

Figure 3.

Proper expression and activity levels of CHW-1 are required for axon guidance. A) Quantitation of PDE defects. lqIs2 is the osm-6::gfp control transgene. At least 100 neurons were scored for each genotype. P < 0.0001 as determined by Fisher Exact Analysis (Graphpad). The error bars represent the standard proportion of the mean. B) A micrograph of a PDE neuron of a WT adult animal (left panel) and a PDE neuron of an adult animal expressing CHW-1(A18G) (right panel). The white lines indicate the outline of the worm. The scale bar represents 5 μm.

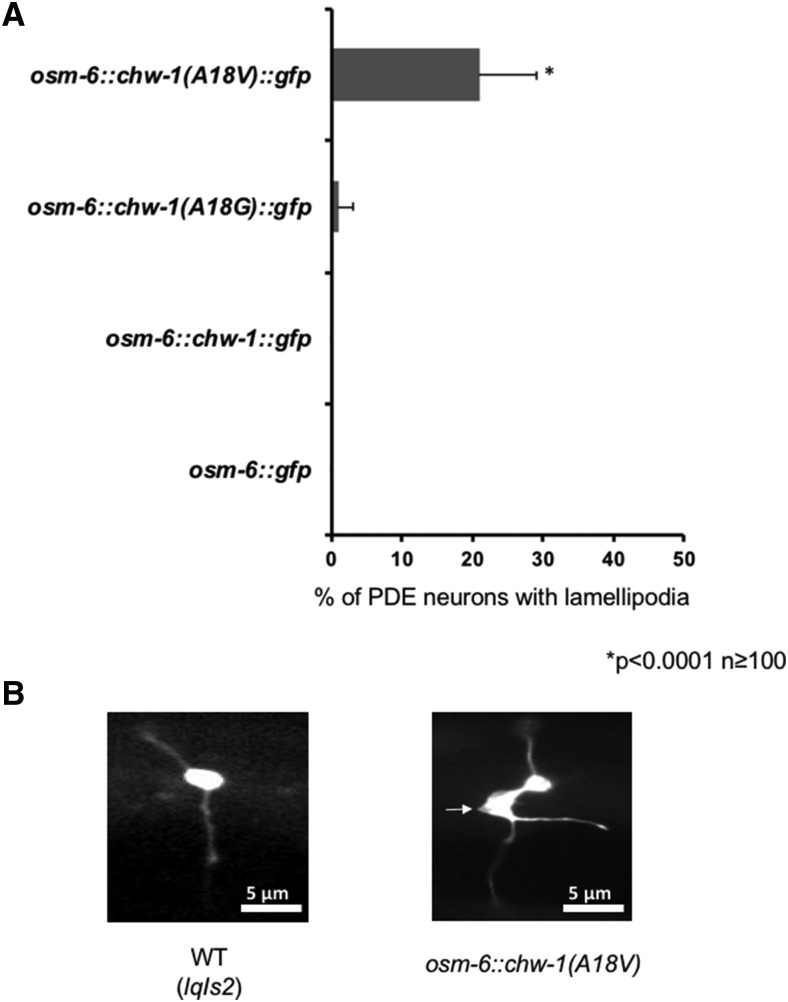

Expression of CHW-1(A18V) results in the formation of ectopic lamellipodia in PDE neurons

Previously, our lab showed that expression of the Rac GTPases CED-10 and MIG-2 harboring the G12V mutation in neurons in vivo resulted in the formation of ectopic lamellipodial and filopodial protrusions (Struckhoff and Lundquist 2003), and that CDC-42(G12V) expression caused similar lamellipodial and filopodial protrusions (Demarco and Lundquist 2010; Demarco et al., 2012). Therefore, we sought to determine whether a similar mutation at this conserved residue, CHW-1(A18V), also resulted in ectopic lamellipodia. Indeed, we found that expression of CHW-1(A18V) resulted in ectopic lamellipodia in 32% of PDE neurons (Figure 4). Expression of wild type CHW-1 or CHW-1(A18G) did not show ectopic lamellipodia. This suggests that like CDC42 and the Rac GTPases, CHW-1 may be involved in regulation of protrusion during neuronal development. Furthermore, these data suggest that full activation by a G12V mutation is necessary for this lamellipodial protrusion.

Figure 4.

Expression of CHW-1(A18V) results in the formation of ectopic lamellipodia in PDE neurons. A) Quantitation of PDE defects. osm-6::gfp is the control transgene. At least 100 neurons were scored for each genotype. P < 0.0001 as determined by Fisher Exact Analysis (Graphpad). The error bars represent the standard proportion of the mean. B) A micrograph of a PDE neuron of a WT adult animal (left panel) and a PDE neuron of an adult animal expressing CHW-1(A18V) (right panel). The white arrow is pointing to the lamellipodia protrusion. The scale bar represents 5 μm.

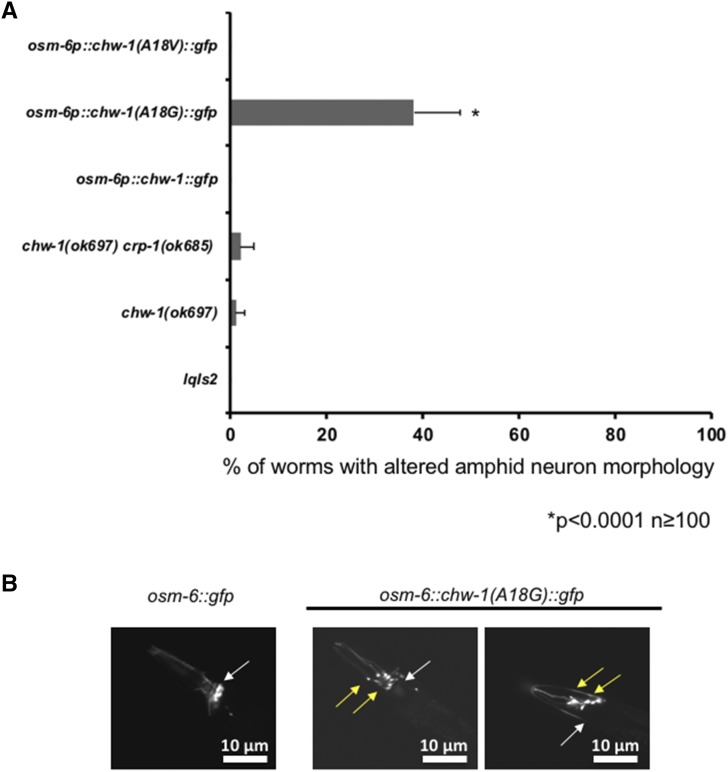

Expression of CHW-1(A18G) results in amphid neuron defects

The osm-6::gfp transgene is expressed in the PDE neurons as well as the sensory amphid neurons in the head and the phasmid neurons in the tail. When examining the PDE neurons in the CHW-1(A18G) mutant, we noticed that the morphology of the amphid neurons in the head was altered. The cell bodies of the amphid neurons in the CHW-1(A18G) transgenic animals were displaced anteriorly (Figure 5). Expression of wild-type CHW-1 or CHW-1(A18V) did not cause anterior amphid displacement. Interestingly, although the osm-6::chw-1(A18G) transgene displayed defects in amphid neuron morphology, the loss of function chw-1(ok697) allele did not display these defects. The chw-1(ok697) crp-1(ok685) double mutant also so showed no amphid neuron defects (Figure 5). The endogenous amino acid at this regulatory position in CHW-1 is an alanine, which is predicted to be a partially activating mutation, suggesting that CHW-1(A18G) may be acting as a dominant-negative in this context.

Figure 5.

Expression of CHW-1(A18G) results in amphid neuron defects. A) Quantitation of amphid neuron defects. lqIs2 is the osm-6::gfp control transgene. The Y-axis denotes the genotype and the X-axis represents the percentage of amphid neuron defects. At least 100 neurons were scored for each genotype. P < 0.0001 as determined by Fisher Exact Analysis (Graphpad). The error bars represent the standard proportion of the mean. B) A micrograph of the amphid neurons of a WT adult animal (left panel), and the amphid neurons of adult animals expressing CHW-1(A18G) (right two panels). The wild-type position of the amphid neuron cell bodies is indicated by the white arrow and the mutant positions are indicated by the yellow arrows. The scale bar represents 10 μm.

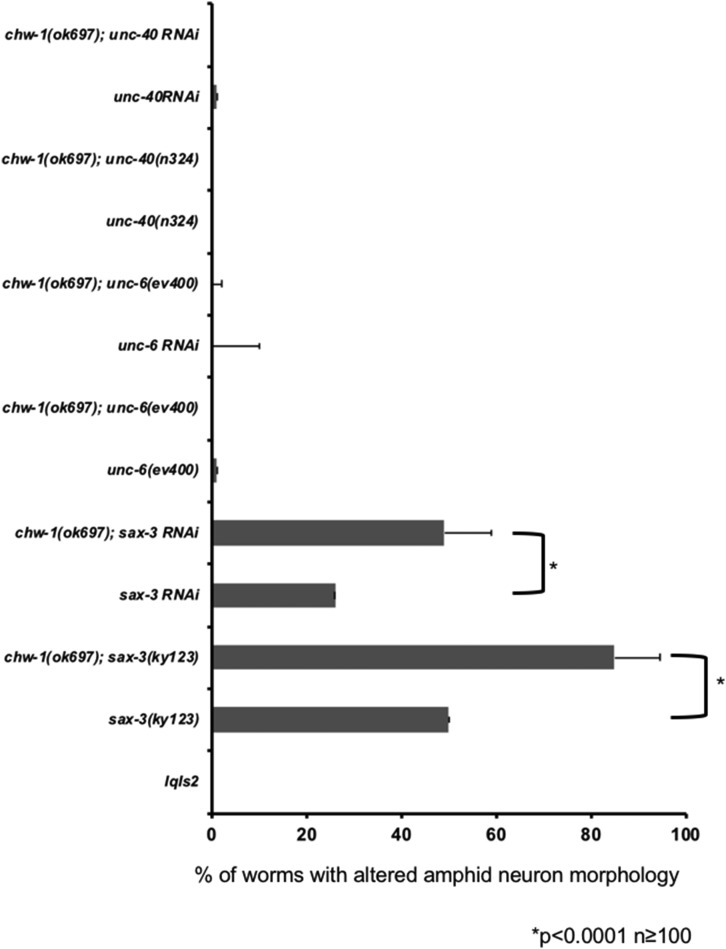

chw-1(ok697) in a sax-3(ky123) background increases amphid neuron defects

We noted that amphid neuron phenotype of CHW-1(A18G) was similar to what was reported for a loss-of-function sax-3 phenotype (Zallen et al. 1999). sax-3 encodes an immunoglobulin guidance receptor similar to vertebrate and Drosophila Robo. We next investigated whether CHW-1 interacts genetically with SAX-3. First, we examined the amount of amphid neuron defects in the loss-of-function sax-3(ky123) animals. We found that 50% of the sax-3(ky123) animals had altered amphid neuron morphologies (Figure 6), similar to what was previously reported in the literature (Zallen et al. 1999). The sax-3(ky123); chw-1(ok697) double mutants displayed a synergistic increase in the amount of amphid neuron defects (Figure 6), suggesting redundant function. We did not observe any genetic interactions between chw-1 and other axon guidance genes such as unc-6 and unc-40.

Figure 6.

Loss of both chw-1 and sax-3, but not other axon guidance molecules, synergistically increases amphid neuron defects. Quantitation of amphid neuron defects. lqIs2 is the osm-6::gfp control transgene. The Y-axis denotes the genotype and the X-axis represents the percentage of amphid neuron defects. At least 100 neurons were scored for each genotype. P < 0.0001 as determined by Fisher Exact Analysis (Graphpad). The error bars represent the standard proportion of the mean.

Loss of both chw-1 and sax-3 increases PDE axon pathfinding defects

Next, we sought to determine whether chw-1 and sax-3 interacted genetically in the context of PDE axon guidance. chw-1(ok697) and sax-3(ky123) alone resulted in PDE axon guidance defects (10% and 40%, respectively) (Figure 7). The double mutant (chw-1(ok697); sax-3(ky123)) displayed an increase in axon pathfinding defects (68%), suggesting that these genes act redundantly in axon pathfinding. We confirmed this result using RNAi against sax-3. Notably, chw-1 showed no significant interactions with unc-6 or unc-40, genes also involved in ventral PDE axon guidance.

Figure 7.

Loss of both chw-1 and sax-3 increases PDE axon pathfinding defects. Quantitation of PDE defects. lqIs2 is the osm-6::gfp control transgene. The Y-axis denotes the genotype and the X-axis represents the percentage of ectopic lamellipodia formation. At least 100 neurons were scored for each genotype. *P < 0.0001 as determined by Fisher Exact Analysis. The error bars represent the standard proportion of the mean.

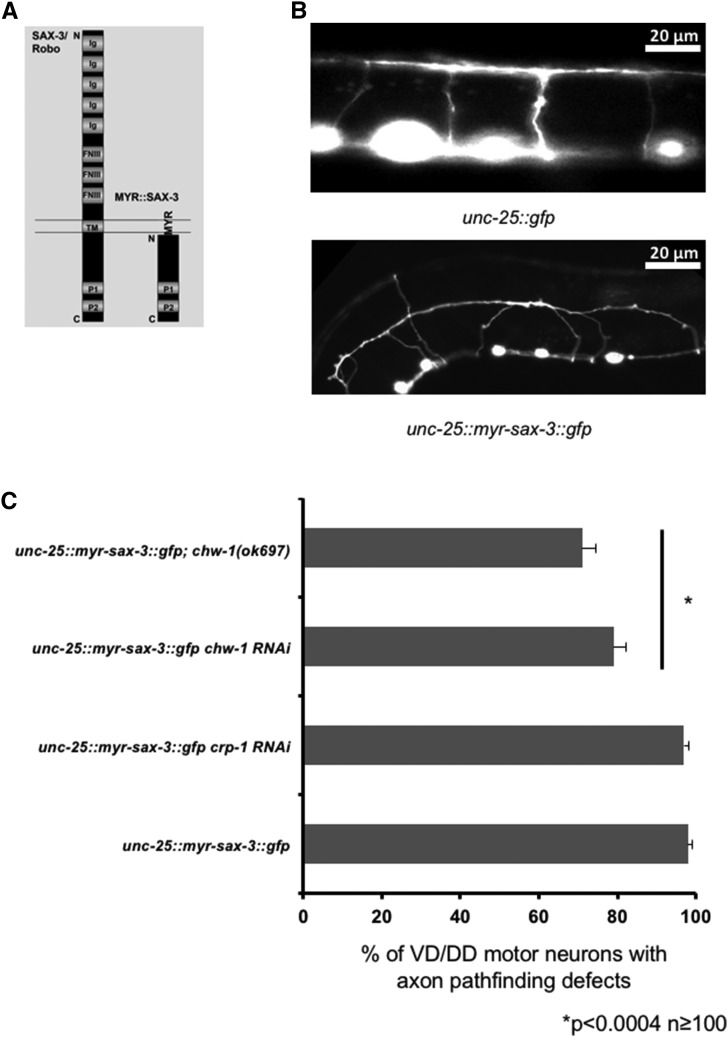

Loss of chw-1 but not crp-1 attenuates the effects of myr::sax-3

Next, we wanted to further define the relationship between CHW-1 and SAX-3. To do this, we constructed a transgene that expressed the cytoplasmic domain of SAX-3 with an N-terminal myristoylation site. In UNC-40/DCC and UNC-5 receptors, a similar myristoylated construct leads to constitutive activation of these receptors (Gitai et al. 2003; Norris and Lundquist 2011; Norris et al. 2014). The MYR::SAX-3 transgene did not display a phenotype in the PDE neurons or in the amphid neurons when driven from the osm-6 promoter. Therefore, we expressed myr::sax-3 in the VD/DD motor neurons using the unc-25 promoter. The VD/DD motor neurons are born in the ventral nerve cord and have axons that extend to the dorsal nerve cord. Dorsal guidance of these commissures is not dependent upon endogenous SAX-3 (Li et al. 2013), however activation of SAX-3 in the neurons significantly alters dorsal axon guidance. We observed that MYR::SAX-3 caused axon pathfinding defects in the majority of VD/DD motor neurons (98%) (Figure 8). Loss of chw-1 significantly attenuated these guidance defects (68%), whereas loss of crp-1 did not. These results were confirmed using RNAi, where loss of chw-1 by RNAi also decreased the axon pathfinding defects in the MYR::SAX-3 background (79%) These data suggest that CHW-1 acts with SAX-3 in axon guidance in the VD/DD motor neurons.

Figure 8.

Loss of chw-1 but not crp-1 attenuates the defects in the VD/DD motor neurons driven by activated SAX-3. A) A representation of the MYR-SAX-3 construct. B) A micrograph of the VD/DD neurons of a WT adult animal (top panel), and the VD/DD neurons of an adult animal expressing MYR-SAX-3 (bottom panel). C) Quantitation of VD/DD defects. unc-25::myr-sax-3 is the activated SAX-3 receptor driven by the unc-25 promoter, which drives expression in the VD/DD motor neurons. The Y-axis denotes the genotype and the X-axis represents the percentage of ectopic lamellipodia formation. The number of axons scored was greater than 100. *P < 0.0004 as determined by Fisher Exact Analysis. The error bars represent the standard proportion of the mean. The scale bar represents 20 μm.

Discussion

Here we show the CDC-42 family members, CHW-1 and CRP-1 contribute to axon guidance in C. elegans, and present evidence suggesting that chw-1 works redundantly with crp-1 and cdc-42 in axon guidance. Furthermore, overexpression of either CHW-1 or CHW-1 GTPase mutants alters axon guidance, suggesting that like the human counterpart Wrch-1, proper levels of CHW-1 expression and activity are required for normal CHW-1 function. For example, in cell culture either knockdown, overexpression or alterations in the GTPase activity of Wrch-1 results in similar disruptions in epithelial cell morphogenesis (Alan et al. 2010; Brady et al. 2009). Taken together, these data suggest that tightly regulated expression and activity levels of CHW-1 and Wrch-1 are required for their normal biological functions.

Next, we showed that a GTPase deficient (activated) mutant of CHW-1, CHW-1(A18V), results in the formation of ectopic lamellipodia in the PDE neuron. This result is similar to the phenotype observed for activated versions of MIG-2, CED-10, and CDC-42 (Struckhoff and Lundquist 2003; Demarco and Lundquist 2010; Demarco et al., 2012), suggesting that, like these canonical GTPases, CHW-1 regulates the actin cytoskeleton. There is evidence that, similar to CDC-42, Wrch-1 also regulates the actin cytoskeleton and is able to regulate the formation of filopodia in cells (Aspenström et al. 2004; Ruusala and Aspenstrom 2008). Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton is critical for many biological and pathological events, including normal cell migration and metastasis. Indeed, Wrch-1 and Chp-1 have been shown to be important in focal adhesion turnover (Ory et al. 2007; Chuang et al. 2007; Aspenström et al. 2004), neural crest cell migration (Faure and Fort 2011; Notarnicola et al. 2008), and T-ALL cell migration (Bhavsar et al. 2013). Further studies should be aimed at examining the specific signaling pathways involved in CHW-1 axon guidance and neuronal migration.

To visualize the PDE neuron we utilized the osm-6 promoter, which also allows visualization of the amphid neurons in the head and the phasmid neurons in the tail (Collet et al. 1998). When we visualized the PDE neuron, we observed that one of the GTPase mutants, CHW-1(A18G), resulted in altered amphid neuron morphology. The amphid neurons are born in the nose, and they migrate anteriorly to their final position where the bodies are located in the anterior region of the pharyngeal bulb and the axons that associate with the nerve ring. We noticed that the amphid neuron cell bodies in the CHW-1(A18G) animals were displaced anteriorly, similar to a loss of functions SAX-3 mutant (Zallen et al. 1999). In most Ras superfamily GTPases, the glycine at position 12 in Ras (position 18 in CHW-1) is highly conserved. Any other amino acid at this position is predicted to hinder the GTPase ability of the protein, rendering the protein at least partially activated. A valine at this position is the strongest activating mutation, resulting in a protein that has no GTPase activity (Wittinghofer et al. 1991) and is insensitive to GAPs, rendering the protein constitutively GTP-bound and active (Ahmadian et al. 1997). Normally, CHW-1 has an alanine at this position (position 18), which is predicted to be partially activating. Therefore, mutation of this alanine to a valine is predicated to be a stronger activation mutation, and mutation to a glycine would be predicted to decrease the activity of this protein. Indeed, when this alanine is mutated to a valine, it results in ectopic lamellipodia formation in the PDE neuron, similar to what is observed in CDC-42, CED-10, and MIG-2 (Shakir et al. 2008; Struckhoff and Lundquist 2003; Demarco and Lundquist 2010). Furthermore, expression of the glycine mutant (CHW-1(A18G)) results in altered amphid neuron morphology, suggesting that CHW-1 activity is required for proper amphid neuron morphology and migration. CHW-1(A18G) may result in decreased function of the protein (by increased GTPase activity), but it also may act as a dominant negative. To further explore the role of CHW-1(A18G), we examined a null allele of chw-1. The null allele did not result in any defects in the amphid neurons, suggesting that CHW-1(A18G) is not acting simply as a protein with decreased function, and may be acting as a dominant negative. Further biochemical studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

This is the second study that examines GTPase mutants of CHW-1. In a paper by Kidd et al. the authors showed that expression of wild-type CHW-1 resulted in errant distal tip cell (DTC) migration when compared to the GFP only negative control (Kidd et al. 2015). The authors also found that expression of CHW-1(A18G) abolished these defects, and expression of an activated CHW-1(A18V) mutant increased these defects, suggesting that native CHW-1 is partially activated. In our hands, ectopic expression of CHW-1 in the PDE neurons caused axon pathfinding defects, and neither GTPase mutant statistically altered the amount of defects, suggesting that in this system increased CHW-1 expression in this system is sufficient to induce axon guidance defects. We also found that activated CHW-1(A18V) induced ectopic lamellipodia in the PDE neurons, similar to the activated versions of other Rho proteins, supporting the findings of Kidd et al. In addition, we found the CHW-1(A18G) mutant may be a dominant negative mutation, complementing the previous findings.

With the CHW-1(A18G) mutant, we found that the amphid neurons were displaced anteriorly, similar to a sax-3 loss of function phenotype. Therefore, we wanted to determine if chw-1 interacted with sax-3 in neuronal guidance. We found that chw-1 interacts genetically with sax-3 in amphid neurons, and in the PDE neurons. We found that loss of chw-1 and sax-3 synergistically increased the defects in amphid neurons and PDE axon pathfinding. While the sax-3(ky123) allele is reported to be a null, these animals are viable (unlike other sax-3 null alleles), suggesting that the sax-3(ky123) allele may retain a small amount of functionality. Thus, we cannot rule out that SAX-3 and CHW-1 might act in the same pathway. Therefore, we conclude that these data suggest that these genes may be working in the same or redundant pathways. To further explore the relationship between chw-1 and sax-3, we added a myristolyation site to sax-3, which results in an activated version of sax-3 (unc-25::myr-sax-3). This modification has been previously used for other guidance receptors, such as UNC-40 (Gitai et al. 2003), to generate constitutively active receptors. Expression of MYR-SAX-3 in the VD/DD motor neurons resulted in axon pathfinding defects. These pathfinding defects were attenuated when we crossed in a null chw-1 allele. These defects were not attenuated in the presence of a null crp-1 allele. These data suggest that chw-1 but not crp-1 are working downstream of sax-3 in axon pathfinding. These data were confirmed with RNAi, which showed that RNAi against chw-1 but not crp-1 decreased the axon guidance defects driven by activated SAX-3.

The C. elegans SAX-3/Robo is a guidance receptor, which acts in anterior–posterior, dorsal–ventral, and midline guidance decisions (Killeen and Sybingco 2008). Binding of the ligand Slit to the SAX-3/Robo receptor deactivates Cdc42 and activates another Rho GTPase, RhoA (Wong et al. 2001). In Drosophila, the adaptor protein Dock directly binds Robo and recruits p-21 activated kinase (Papakonstanti and Stournaras 2004) and Sos, thus increasing Rac activity (Fan et al. 2003). Here, we show that there is a genetic interaction between sax-3 and chw-1, and that chw-1 is likely working downstream of sax-3 in the VD/DD motor neurons. Activation of SAX-3 likely also results in signaling through CHW-1, in addition to other Rho GTPases, to mediate axon guidance. SAX-3/Robo signaling has also been implicated in carcinogenesis. Slit2 expression occurs in a large number of solid tumors, and Robo1 expression occurs in parallel in vascular endothelial cells. Concurrent expression of these proteins results in angiogenesis and increased tumor mass (Wang et al. 2003). Furthermore, mutations in SLT2, ROBO1, and ROBO2 are implicated in pancreatic ductal adenocarinoma (Biankin et al. 2012). Although the mammalian homologs Wrch-1 and Chp have been implicated in epithelial cell morphogenesis (Brady et al. 2009; Alan et al. 2010), migration (Ory et al. 2007; Chuang et al. 2007; Faure and Fort 2011), and anchorage-independent growth, the exact mechanisms by which these processes occur remains to be fully elucidated. One possible mechanism may be SAX-3/Robo signaling through CHW-1/Wrch-1, and data from another study suggest that defects in polarity driven by CHW-1/Wrch-1 may contribute to these processes (Kidd et al. 2015). Further studies will be aimed at determining the precise mechanism by which these two molecules interact in both normal physiological processes and aberrant pathological processes.

In summary, we have shown that chw-1 works redundantly with crp-1 and cdc-42 in axon guidance. Furthermore, proper levels and activity of CHW-1 are required for proper axon guidance in C. elegans. Importantly, we were able to show that CHW-1 is working downstream of the guidance receptor SAX-3/Robo. This novel pathway is important in axon guidance and may be important in development in addition to other pathogenic processes such as tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, and metastasis.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: D. Fay

Literature Cited

- Ahmadian M. R., Hoffmann U., Goody R. S., Wittinghofer A., 1997. Individual rate constants for the interaction of Ras proteins with GTPase-activating proteins determined by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry 36(15): 4535–4541. 10.1021/bi962556y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alan J. K., Berzat A. C., Dewar B. J., Graves L. M., Cox A. D., 2010. Regulation of the Rho family small GTPase Wrch-1/RhoU by C-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation requires Src. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30(17): 4324–4338. 10.1128/MCB.01646-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronheim A., Broder Y. C., Cohen A., Fritsch A., Belisle B., et al. , 1998. Chp, a homologue of the GTPase Cdc42Hs, activates the JNK pathway and is implicated in reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol. 8(20): 1125–1128. 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70468-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenström P., Fransson A., Saras J., 2004. Rho GTPases have diverse effects on the organization of the actin filament system. Biochem. J. 377(Pt 2): 327–337. 10.1042/bj20031041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzat A. C., Buss J. E., Chenette E. J., Weinbaum C. A., Shutes A., et al. , 2005. Transforming activity of the Rho family GTPase, Wrch-1, a Wnt-regulated Cdc42 homolog, is dependent on a novel carboxyl-terminal palmitoylation motif. J. Biol. Chem. 280(38): 33055–33065. 10.1074/jbc.M507362200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar P. J., Infante E., Khwaja A., Ridley A. J., 2013. Analysis of Rho GTPase expression in T-ALL identifies RhoU as a target for Notch involved in T-ALL cell migration. Oncogene 32(2): 198–208. 10.1038/onc.2012.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biankin A. V., Waddell N., Kassahn K. S., Gingras M. C., Muthuswamy L. B., et al. , 2012. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature 491(7424): 399–405. 10.1038/nature11547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady D. C., Alan J. K., Madigan J. P., Fanning A. S., Cox A. D., 2009. The transforming Rho family GTPase Wrch-1 disrupts epithelial cell tight junctions and epithelial morphogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29(4): 1035–1049. 10.1128/MCB.00336-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier H., Pawlak G., Vives V., Blangy A., 2009. The Rho GTPase Wrch1 regulates osteoclast precursor adhesion and migration. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41(6): 1391–1401. 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier H., Stephens S., Ory S., Fort P., Morrison N., et al. , 2006. Expression profile of RhoGTPases and RhoGEFs during RANKL-stimulated osteoclastogenesis: identification of essential genes in osteoclasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21(9): 1387–1398. 10.1359/jbmr.060613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77(1): 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso M. E., Jenna S., Bouchecareilh M., Baillie D. L., Boismenu D., et al. , 2008. GTPase-mediated regulation of the unfolded protein response in Caenorhabditis elegans is dependent on the AAA+ ATPase CDC-48. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28(13): 4261–4274. 10.1128/MCB.02252-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenette E. J., Abo A., Der C. J., 2005. Critical and distinct roles of amino- and carboxyl-terminal sequences in regulation of the biological activity of the Chp atypical Rho GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 280(14): 13784–13792. 10.1074/jbc.M411300200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenette E. J., Mitin N. Y., Der C. J., 2006. Multiple sequence elements facilitate Chp Rho GTPase subcellular location, membrane association, and transforming activity. Mol. Biol. Cell 17(7): 3108–3121. 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Y. Y., Valster A., Coniglio S. J., Backer J. M., Symons M., 2007. The atypical Rho family GTPase Wrch-1 regulates focal adhesion formation and cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 120(Pt 11): 1927–1934. 10.1242/jcs.03456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet J., Spike C. A., Lundquist E. A., Shaw J. E., Herman R. K., 1998. Analysis of osm-6, a gene that affects sensory cilium structure and sensory neuron function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 148(1): 187–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Toledo M., Senic-Matuglia F., Salamero J., Uze G., Comunale F., et al. , 2003. The GTP/GDP cycling of rho GTPase TCL is an essential regulator of the early endocytic pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 14(12): 4846–4856. 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarco R. S., Lundquist E. A., 2010. RACK-1 acts with Rac GTPase signaling and UNC-115/abLIM in Caenorhabditis elegans axon pathfinding and cell migration. PLoS Genet. 6(11): e1001215 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarco R. S., Struckhoff E. C., Lundquist E. A. 2012. The Rac GTP exchange factor TIAM-1 acts with CDC-42 and the guidance receptor UNC-40/DCC in neuronal protrusion and axon guidance. PLoS Genet. 8(4): e1002665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson B. J., 2001. Rho GTPases in growth cone guidance. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11(1): 103–110. 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00180-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson B. J., 2002. Molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Science 298(5600): 1959–1964. 10.1126/science.1072165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S., Hall A., 2002. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature 420(6916): 629–635. 10.1038/nature01148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Labrador J. P., Hing H., Bashaw G. J., 2003. Slit stimulation recruits Dock and Pak to the roundabout receptor and increases Rac activity to regulate axon repulsion at the CNS midline. Neuron 40(1): 113–127. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00591-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure S., Fort P., 2011. Atypical RhoV and RhoU GTPases control development of the neural crest. Small GTPases 2(6): 310–313. 10.4161/sgtp.18086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G., Letourneau P., 2002. Axon guidance: proteins turnover in turning growth cones. Curr. Biol. 12(16): R560–R562. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01054-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitai Z., Yu T. W., Lundquist E. A., Tessier-Lavigne M., Bargmann C. I., 2003. The netrin receptor UNC-40/DCC stimulates axon attraction and outgrowth through enabled and, in parallel, Rac and UNC-115/AbLIM. Neuron 37(1): 53–65. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01149-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guémar L., de Santa Barbara P., Vignal E., Maurel B., Fort P., et al. , 2007. The small GTPase RhoV is an essential regulator of neural crest induction in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 310(1): 113–128. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A. B., Hall A., 2005. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21(1): 247–269. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenna S., Caruso M. E., Emadali A., Nguyen D. T., Dominguez M., et al. , 2005. Regulation of membrane trafficking by a novel Cdc42-related protein in Caenorhabditis elegans epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 16(4): 1629–1639. 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Jorgensen E., Hartwieg E., Horvitz H. R., 1999. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene unc-25 encodes glutamic acid decarboxylase and is required for synaptic transmission but not synaptic development. J. Neurosci. 19(2): 539–548. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00539.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., Ahringer J., 2003. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30(4): 313–321. 10.1016/S1046-2023(03)00050-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd A. R., 3rd, Muniz-Medina V., Der C. J., Cox A. D., Reiner D. J., 2015. The C. elegans Chp/Wrch Ortholog CHW-1 Contributes to LIN-18/Ryk and LIN-17/Frizzled Signaling in Cell Polarity. PLoS One 10(7): e0133226 10.1371/journal.pone.0133226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen M. T., Sybingco S. S., 2008. Netrin, Slit and Wnt receptors allow axons to choose the axis of migration. Dev. Biol. 323(2): 143–151. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Pu P., Le W., 2013. The SAX-3 receptor stimulates axon outgrowth and the signal sequence and transmembrane domain are critical for SAX-3 membrane localization in the PDE neuron of C. elegans. PLoS One 8(6): e65658 10.1371/journal.pone.0065658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist E. A., 2003. Rac proteins and the control of axon development. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13(3): 384–390. 10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00071-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., 2000. Rho GTPases in neuronal morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1(3): 173–180. 10.1038/35044547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C., Fire A., 1995. DNA transformation. Methods Cell Biol. 48: 451–482. 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)61399-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson D., Silletti J., Murphy G., D’Eustachio P., Rush M., et al. , 2001. Differential localization of Rho GTPases in live cells: regulation by hypervariable regions and RhoGDI binding. J. Cell Biol. 152(1): 111–126. 10.1083/jcb.152.1.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G. A., Jillian S. A., Michaelson D., Philips M. R., D’Eustachio P., et al. , 2001. Signaling mediated by the closely related mammalian Rho family GTPases TC10 and Cdc42 suggests distinct functional pathways. Cell Growth Differ. 12(3): 157–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G. A., Solski P. A., Jillian S. A., Perez de la Ossa P., D’Eustachio P., et al. , 1999. Cellular functions of TC10, a Rho family GTPase: regulation of morphology, signal transduction and cell growth. Oncogene 18(26): 3831–3845. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris A. D., Lundquist E. A., 2011. UNC-6/netrin and its receptors UNC-5 and UNC-40/DCC modulate growth cone protrusion in vivo in C. elegans. Development 138(20): 4433–4442. 10.1242/dev.068841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris A. D., Sundararajan L., Morgan D. E., Roberts Z. J., Lundquist E. A., 2014. The UNC-6/Netrin receptors UNC-40/DCC and UNC-5 inhibit growth cone filopodial protrusion via UNC-73/Trio, Rac-like GTPases and UNC-33/CRMP. Development 141(22): 4395–4405. 10.1242/dev.110437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notarnicola C., Le Guen L., Fort P., Faure S., de Santa Barbara P., 2008. Dynamic expression patterns of RhoV/Chp and RhoU/Wrch during chicken embryonic development. Dev. Dyn. 237(4): 1165–1171. 10.1002/dvdy.21507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S., Yamada E., Saito T., Ohshima K., Hashimoto K., et al. , 2008. CDK5-dependent phosphorylation of the Rho family GTPase TC10(alpha) regulates insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 283(51): 35455–35463. 10.1074/jbc.M806531200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory S., Brazier H., Blangy A., 2007. Identification of a bipartite focal adhesion localization signal in RhoU/Wrch-1, a Rho family GTPase that regulates cell adhesion and migration. Biol. Cell 99(12): 701–716. 10.1042/BC20070058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstanti E. A., Stournaras C., 2004. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promotes survival of opossum kidney cells via Cdc42-induced phospholipase C-gamma1 activation and actin filament redistribution. Mol. Biol. Cell 15(3): 1273–1286. 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley A. J., 2004. Rho proteins and cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 84(1): 13–19. 10.1023/B:BREA.0000018423.47497.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruusala A., Aspenstrom P., 2008. The atypical Rho GTPase Wrch1 collaborates with the nonreceptor tyrosine kinases Pyk2 and Src in regulating cytoskeletal dynamics. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28(5): 1802–1814. 10.1128/MCB.00201-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T., 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- Saras J., Wollberg P., Aspenstrom P., 2004. Wrch1 is a GTPase-deficient Cdc42-like protein with unusual binding characteristics and cellular effects. Exp. Cell Res. 299(2): 356–369. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakir M. A., Jiang K., Struckhoff E. C., Demarco R. S., Patel F. B., et al. , 2008. The Arp2/3 activators WAVE and WASP have distinct genetic interactions with Rac GTPases in Caenorhabditis elegans axon guidance. Genetics 179(4): 1957–1971. 10.1534/genetics.108.088963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepelev M. V., Chernoff J., Korobko I. V., 2011. Rho family GTPase Chp/RhoV induces PC12 apoptotic cell death via JNK activation. Small GTPases 2(1): 17–26. 10.4161/sgtp.2.1.15229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepelev M. V., Korobko I. V., 2012. Pak6 protein kinase is a novel effector of an atypical Rho family GTPase Chp/RhoV. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 77(1): 26–32. 10.1134/S0006297912010038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutes A., Berzat A. C., Chenette E. J., Cox A. D., Der C. J., 2006. Biochemical analyses of the Wrch atypical Rho family GTPases. Methods Enzymol. 406: 11–26. 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)06002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutes A., Berzat A. C., Cox A. D., Der C. J., 2004. Atypical mechanism of regulation of the Wrch-1 Rho family small GTPase. Curr. Biol. 14(22): 2052–2056. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struckhoff E. C., Lundquist E. A., 2003. The actin-binding protein UNC-115 is an effector of Rac signaling during axon pathfinding in C. elegans. Development 130(4): 693–704. 10.1242/dev.00300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W., Pennica D., Xu L., Kalejta R. F., Levine A. J., 2001. Wrch-1, a novel member of the Rho gene family that is regulated by Wnt-1. Genes Dev. 15(14): 1796–1807. 10.1101/gad.894301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier-Lavigne M., Goodman C. S., 1996. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science 274(5290): 1123–1133. 10.1126/science.274.5290.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignal E., De Toledo M., Comunale F., Ladopoulou A., Gauthier-Rouviere C., et al. , 2000. Characterization of TCL, a new GTPase of the rho family related to TC10 andCcdc42. J. Biol. Chem. 275(46): 36457–36464. 10.1074/jbc.M003487200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Xiao Y., Ding B. B., Zhang N., Yuan X., et al. , 2003. Induction of tumor angiogenesis by Slit-Robo signaling and inhibition of cancer growth by blocking Robo activity. Cancer Cell 4(1): 19–29. 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00164-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittinghofer F., Krengel U., John J., Kabsch W., Pai E. F., 1991. Three-dimensional structure of p21 in the active conformation and analysis of an oncogenic mutant. Environ. Health Perspect. 93: 11–15. 10.1289/ehp.919311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K., Ren X. R., Huang Y. Z., Xie Y., Liu G., et al. , 2001. Signal transduction in neuronal migration: roles of GTPase activating proteins and the small GTPase Cdc42 in the Slit-Robo pathway. Cell 107(2): 209–221. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00530-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W. (Editor), 1988. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Zallen J. A., Kirch S. A., Bargmann C. I., 1999. Genes required for axon pathfinding and extension in the C. elegans nerve ring. Development 126(16): 3679–3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. S., Koenig A., Young C., Billadeau D. D., 2011. GRB2 couples RhoU to epidermal growth factor receptor signaling and cell migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 22(12): 2119–2130. 10.1091/mbc.E10-12-0969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article. Strains are available upon request.