Abstract

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) results from incomplete formation of the diaphragm leading to herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity. CDH is associated with pulmonary hypoplasia, congenital heart disease, and pulmonary hypertension. Genetically, it is associated with aneuploidies, chromosomal copy-number variants, and single gene mutations. CDH is the most expensive noncardiac congenital defect. Management frequently requires implementation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which increases management expenditures 2.4–3.5-fold. The cost of management of CDH has been estimated to exceed $250 million per year. Despite in-hospital survival of 80%–90%, current management is imperfect, as a great proportion of surviving children have long-term functional deficits. We report the case of a premature infant prenatally diagnosed with CDH and congenital heart disease, who had a protracted and complicated course in the intensive care unit with multiple surgical interventions, including postcardiac surgery ECMO, gastrostomy tube placement with Nissen fundoplication, tracheostomy for respiratory failure, recurrent infections, and developmental delay. Rapid whole-genome sequencing (rWGS) identified a de novo, likely pathogenic, c.3096_ 3100delCAAAG (p.Lys1033Argfs*32) variant in ARID1B, providing a diagnosis of Coffin–Siris syndrome. Her parents elected palliative care and she died later that day.

Keywords: anteverted nares, aplasia/hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, central hypotonia, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, congenital mitral stenosis, failure to thrive in infancy, frontal hirsutism, malrotation of small bowel, moderate global developmental delay, perimembranous ventricular septal defect, postductal coarctation of the aorta, recurrent respiratory infections

CASE PRESENTATION

The patient was a 7-mo-old girl, product of a diamniotic–dichorionic twin pregnancy, and born at 34 wk gestation. She was small for gestational age, with a birth weight of 1.49 kg (<3rd percentile). She was prenatally diagnosed with left congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), aortic arch hypoplasia, small left-sided cardiac structures, and ventricular septal defect. Genetic amniocentesis documented a normal, 46, XX karyotype and normal chromosomal microarray. The family was counseled as to a poor likelihood for survival based on a heart–lung ratio of 0.86, but elected to carry the twin pregnancy. She required significant respiratory and inotropic support postbirth but was able to undergo CDH repair on day of life (DOL) 5. At 3 mo of age she underwent aortic arch hypoplasia repair with ventricular septal defect closure. Her postoperative course was complicated by arrhythmias and acute hypotension leading to venoarterial (VA)-ECMO cannulation on postoperative day 1 (POD1). She was decannulated on POD4 and underwent delayed sternal closure on POD6. Her hospitalization was further complicated by eight culture-positive respiratory infections with Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria between her second week of life and death at 8 mo of age. She received multiple courses of antibiotics for suspected infection. She had feeding intolerance and underwent a Nissen Gastrostomy tube placement at 4 mo of age. Genetics consultation at 5 mo of age documented a delayed, dysmorphic, and hirsute infant with unusual penciled eyebrows, a medial eyebrow flare, anteverted nares, and posteriorly rotated ears, but well developed nails with no distal phalangeal hypoplasia (Table 1). A specific pattern of malformation was not recognized. A postnatal microarray was normal. Exome sequencing was suggested, but the funding was not approved. At 6 mo of age she underwent exploratory laparotomy for lysis of adhesions in the setting of a small bowel obstruction. There was no bowel loss. She was reintubated at 7 mo of age for respiratory failure. At that time she also developed atrial flutter requiring medical cardioversion with sotalol. She failed a trial of extubation and underwent a tracheostomy for procurement of a more stable airway. Sotalol was discontinued after 9 d of treatment in the setting of high-grade atrioventricular block. She had chronic lung disease (CLD), iatrogenic neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), persistent electrolyte derangements, and refractory metabolic alkalosis on diuretic therapy. The option for palliative care was presented on multiple occasions during the patient's hospitalization. Parental consensus on a decision could never be reached as one of the parents held out hope that advancements in technology would address most of the patient's health concerns in the absence of a confirmed diagnosis. Soon after referral for rapid whole-genome sequencing (rWGS), she developed another episode of respiratory failure requiring oscillatory ventilation. At the time of rWGS diagnosis she was found to be in septic shock requiring inotropic support with multiple agents. After meeting with genetic specialists to discuss the diagnosis and prognosis, the family opted for withdrawal of life support given the patient's critical condition and the fact that the underlying genetic condition could not be cured.

Table 1.

Phenotypic features of Coffin–Siris syndrome

| Feature | Proband (II-1)a | Relevance/alternate explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Short stature | Yes | Length < 3% on WHO Girls (0–2 yr) gestation adjusted chart |

| Coarse facies | Yes | |

| Facial hypertrichosis | Yes | Chronic steroid administration |

| Low-set ears/posteriorly rotated ears | No | |

| Visual impairment/strabismus/downslanting palpebral fissures | No | |

| Bushy eyebrows | Nob | Patient with unusual eyebrow pattern but not bushy |

| Long eyelashes | Yes | |

| Broad nasal tip | Nob | |

| Large mouth/thin upper lip vermilion/thick lower lip vermilion | Nob | |

| Delayed dentition | No | |

| Frequent upper and lower respiratory tract infections (early life) | Yes | |

| Feeding problems | Yes | |

| Skeletal anomalies including hypoplastic to absent terminal phalanges hands and feet | Nob | |

| Lumbosacral hirsutism/sparse scalp hair/hypertrichosis | Yes | |

| Delayed psychomotor development | Yes | |

| Moderate to severe hypotonia | Yes | |

| Seizures (in some patients) | No | |

| Intellectual disability | ND | Unable to assess because of age |

| Moderate to severe hypotonia | Yes | |

| Hypoplastic corpus callosum (in some patients) | Yes | |

| Partial agenesis of corpus callosum (in some patients) | No |

The list of clinical features is modified from the OMIM clinical synopsis (#135900; CSS).

ND, not determined.

aNone of these features were seen in the parents.

bUnusual feature.

The patient had an unaffected 7-yr-old brother and an unaffected twin brother. Her parents were both healthy. Her mother, age 37, identified as Hispanic and her father, age 42, as Caucasian Italian. Her mother had a history of a miscarriage at 3 mo gestation prior to this twin pregnancy. There was a maternal female cousin born with tricuspid atresia, who had required at least four surgeries.

TECHNICAL ANALYSIS AND METHODS

The patient had a normal newborn screen, normal female karyotype (prenatal testing), and a normal female chromosomal microarray both prenatally (ARUP) and postnatally (Quest Diagnostics). rWGS became available during her seventh month of life.

One day after consent for trio rWGS, DNA was extracted and sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq X (Hudson Alpha) with paired 151-nt reads. The average library insert size was 369 nt for proband. Sequencing was completed 7 d after consent. Rapid alignment and nucleotide-variant calling was performed using the Dragen (Edico Genome) hardware and software (Miller et al. 2005). Yield was 195.5 Gb for the proband with a median coverage of 52× (51× coverage for genes annotated in Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM) resulting in 4,945,287 distinct variant calls (4,059,083 single-nucleotide variants [SNVs], 886,204 small insertion deletion variants [indels], 27,343 coding domain [CD] variants, with a Ti/Tv ratio of 2.04) (Supplemental Table S1). Variants were automatically annotated and analyzed in Opal Clinical (Omicia) (Coonrod et al. 2013). Initially, variants were filtered to retain those with allele frequencies of <1% in the Exome Variant Server, 1000 Genomes Samples, and Exome Aggregation Consortium database (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ 2016; Karczewski et al. 2016). A differential diagnostic gene list was built in Phenolyzer (Yang et al. 2015) using the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) (Kohler et al. 2017) and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT [SNOMED 2016]) codes: Small for Gestational Age (HP:0001511), Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (HP:0000776), Congenital Heart Disease (HP:0030680), Coarctation of the Aorta (HP:0001680), Perimembranous Ventricular Septal Defect (HP:0011682), Mitral Stenosis (HP:0011570), Malrotation (HP:0002566), Failure to Thrive (HP:0001531), Hypoplasia of Corpus Callosum (HP:0002079), Asymmetric Hippocampal Bodies (L smaller than R), Dysmorphic Facial Features (HP:0001999), Long Eyelashes (HP:0000527), Flared Eyebrows (HP:0011229), Frontal Hirsutism (Hairy Forehead, HP:0011335), Anteverted Nose (HP:0000463), Low Nasal Bridge (HP:0005280), Hypotonia (HP:0008947), Thin Sparse Hair (HP:0008070), Developmental Delay (HP:0002194), and Frequent Respiratory Infections (HP:0002205), yielding 1678 genes. Variants were further filtered to retain those mapping to these 1678 genes using the differential diagnostic gene list built in Phenolyzer, yielding three variants of interest. Variants were assessed in accordance with ACMG variant classification criteria (Richards et al. 2015). Two variants were classified as variants of uncertain significance: c.422A>C (p.Glu141Ala) in NDUFAF4, and c.685_686insCGC (p.Gln228_Gln229insPro) in SMARCA2. The ARID1B p.Lys1033Argfs*32 was classified as likely pathogenic (Supplemental Table S2) and was confirmed by Sanger Sequencing.

VARIANT INTERPRETATION

Interpretation of the rWGS results for this patient determined a de novo alteration in the AT-rich DNA interacting domain-containing protein 1B (ARID1B) gene, c.3096_3100delCAAAG (p.Lys1033ArgfsTer32), following genetic analysis of proband and both parents (Table 2). ARID1B is a component of a chromatin remodeling complex involved in cell cycle activation and is one of the genes that cause Coffin–Siris syndrome (CSS). CSS is a multisystem disease associated with congenital anomalies (congenital diaphragmatic hernia, spinal anomalies, and congenital heart defects), dysmorphic features, recurrent infections, and developmental delay. The prevalence of CSS has been estimated at <1:100,000. Multiple genes have been implicated in this syndrome including ARID1A, ARID1B, SMARCA2, SMARCA4, SMARCB1, and SMARCE1 (Tsurusaki et al. 2012). Inheritance is autosomal dominant. The major features of CSS are intellectual disability, speech delay, coarse facies, and hypertrichosis. Prevalent features are hypoplasia of the fifth digits/nails of hand/feet, feeding difficulties, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Other more variable features include poor overall growth, craniofacial abnormalities, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, spinal anomalies, and congenital heart defects (Santen et al. 2014). The classic phenotype of CSS with hypoplastic distal phalanges and nails of the fifth fingers, the most distinct and objective of the classic features of CSS, is not always seen. As with many other conditions, the identification of the molecular basis of a specific condition has led to the expansion of the clinical phenotype, and features such as hypertrichosis, hypoplastic nails, or obvious coarse facial features have been found to be more subtle or absent in many cases. Others, such as hyperkeratosis, have only been recently recognized (Zweier et al. 2017). More importantly, ARID1B is now recognized as one of the most frequent genes causing nonsyndromic intellectual disability (Santen et al. 2014).

Table 2.

Genomic findings

| Gene | Genomic location | HGVS cDNA | HGVS protein | Zygosity | Parent of origin | Variant interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARID1B | NM_020732.3: Chr 6:157495211GCAAAG>G | c.3096_3100delCAAAG | p.Lys1033Argfs*32 | Heterozygous | De novo | Likely pathogenic |

HGVS, Human Genome Variation Society.

The c.3096_3100delCAAAG (p.Lys1033ArgfsTer32) in ARID1B is a novel frameshift alteration leading to a premature termination codon. This deletion was not found in the 1000 Genomes, Exome Variant Server (EVS), or ExAC databases. Thus, it is presumed to be rare. Although this particular variant has not been reported in the literature, pathogenic alterations similar to this one have been reported (Hoyer et al. 2012). Based on the combined evidence, this variant is classified as likely pathogenic for CSS.

The incidence of CDH is 1 in 2000–5000 births (Chen et al. 2007a), and it comprises 8% of all birth defects (Yu et al. 2015). It is the cause of 1%–2% of infant mortalities. CDH is caused by the incomplete formation of the diaphragm around the fourth to eighth week of gestation. Greater than 95% form posterior lateral (Bochdaleck) and ∼2% are anterior retrosternal or parasternal. Eighty-five percent of CDHs are on the left side of the body. Forty percent of CDH cases are associated with at least one additional anomaly like pulmonary hypoplasia, congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, or other genetic anomalies (Yu et al. 2015).

More than 50 different genetic syndromes have been associated with CDH, ranging from aneuploidies (trisomy 18 is seen in 1%–2% of CDH), copy-number variations (tetrasomy 12p, 8p23.1 deletion, 15q26.1 deletion, 1q41-42 deletion, 8q23.1 deletion, 4p16 deletion, 11q23.2 deletion) (Wynn et al. 2014; Stark et al. 2015), autosomal dominant disorders (WT1-opathies, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Kabuki syndrome), autosomal recessive disorders (Fryns syndrome), and X-linked disorders (craniofrontonasal syndrome, Simpson–Golabi–Behmel, focal dermal hypoplasia). Nonsyndromic single gene mutations (GATA4, ZFPM2/FOG2, DIPS1) have also been reported. The causes of 80% of CDH cases are still unknown and are thought to be multifactorial (Wynn et al. 2014), although some genetic cases may not be detected by current testing strategies.

CDH is associated with a high rate of functional impairment. In a cross-sectional study of CDH repair survivors at Boston Children's Hospital, it was found that 66% had major medical issues at discharge, whereas 48% still had a current clinical problem on follow-up around 8 yr of age (Chen et al. 2007a). Neonatal predictors of ongoing medical morbidity were prior ECMO use, presence of cardiac disease, and associated genetic abnormalities. Medical problems reported were related to vision, hearing, muscle weakness, speech, behavior, learning, eating, and breathing (Chen et al. 2007b).

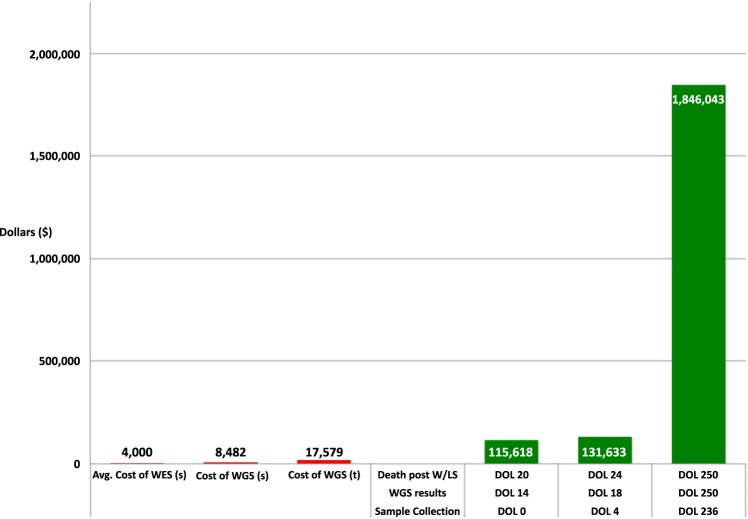

CDH is the most expensive noncardiac congenital anomaly. Based on the analysis of data obtained from approximately 200 hospitals in the United States (KID database; https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp) from 1997 to 2006, it is estimated that the national cost for management of surviving CDH patients is ∼$158 million/yr. The national cost for management of all CDH patients (including the ones who do not survive to discharge) is >$250 million/yr. ECMO support is associated with a 2.4–3.5-fold increase in expenditure (Raval et al. 2011). Figure 1 shows the cumulative hospital costs at the time of the patient's death, which were >$1.8 million. The cost of rWGS at the time was $8482 for a singleton and $17,579 for a trio. The average cost of commercial WES including analysis is estimated at $4000. At our institution WES is usually performed outpatient with a turnaround time of 6–8 wk because this test is not covered while inpatient. Hospital cost for taking care of this child if she were referred to us on DOL0, assuming a rWGS diagnosis on DOL14 (the results for this patient were available by day 7 of enrollment) and time of death of 6 d following approach of the family for withdrawal of life support (W/LS), would have been a little more than $115,000. Literature review shows that the time from approach of families for W/LS to the child's death can range anywhere from 2–6 d depending on whether the patient is in the United States or Europe (Keenan et al. 1997; Garros et al. 2003; Devictor et al. 2008). The cost if referred on DOL4 would have been a little more than $130,000. If we are willing to spend more than $1.8 million attempting to improve the quality of life of these critically ill children, this case demonstrates that the cost of genomic sequencing should not be prohibitive to its implementation in their care.

Figure 1.

Cumulative hospital costs at the time of the patient's death, which was >1.8 million dollars. Estimated cost of rapid whole-genome sequencing (rWGS) at the time patient was sequenced was $8482 in a singleton and $17,579 for a trio. Estimated cost of whole-exome sequencing (WES) with interpretation on average $4000. Hospital cost for taking care of this child if she was referred to us on DOL0, assuming a diagnosis on DOL14 and time of death of 6 d post approach of families for W/LS, would have been a little more than $115,000. The cost if referred on DOL4 would have been a little more than $130,000. This figure illustrates that the cost of genomic sequencing would not have been prohibitive even if the patient had been referred for sequencing early in the course of her treatment.

SUMMARY

CDH is the most expensive noncardiac congenital anomaly and is associated with significant long-term functional impairment. Genetic testing should be pursued early in the management of infants with CDH given myriad potential genetic etiologies. In this case rWGS allowed identification of a single gene disorder with long-term implications for outcome that assisted in the management of the patient. For this particular patient earlier diagnosis may have shortened the clinical course, obviating suffering for the patient and family and reducing expenditures for the health-care system.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Data Deposition and Access

The data were deposited under ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) accession number SCV000584044.

Ethics Statement

Informed and signed consent forms were obtained for all sequenced individuals of this study. The project is approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California at San Diego under protocol #160468.

Acknowledgments

The Rady Children's Institute for Genomic Medicine Investigators involved in this project were Stephen F. Kingsmore, Joseph Gleeson, David Dimmock, Mathew Bainbridge, Shareef Nahas, Shimul Chowdhury, Amber Hildreth, Lauge Farnaes, Nathaly Sweeney, Jennifer Friedman, Michelle Clark, Yan Ding, Luca Van Der Kraan, Laura Puckett, Catherine Yamada, Jennifer Silhavy, Julie Cakici, Sara Martin, Lisa Salz, Narayanan Veeraraghavan, Sergey Bartalov, Danny Oh, George Chang, and Julie Ryu.

Author Contributions

N.M.S. contributed to manuscript preparation and phenotyping; S.A.N. contributed to variant interpretation and manuscript preparation; S.C. contributed to variant interpretation and manuscript preparation; M.D.C. contributed to clinical implementation and manuscript preparation; M.C.J. contributed to clinical implementation and manuscript preparation; D.P.D contributed to manuscript preparation and supervised the study; S.F.K. contributed to manuscript preparation and supervised the study; and the RCIGM Investigators contributed to process development, infrastructure deployment, and maintenance. All authors contributed to the reviewing of the final version.

Funding

This study was supported by Rady Children's Hospital and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and National Human Genome Research Institute grant U19HD077693.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

Referees

Peter Robinson

Anonymous

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

REFERENCES

- Chen C, Jeruss S, Chapman JS, Terrin N, Toghiouart H, Glassman E, Wilson JM, Parsons SK. 2007a. Long-term functional impact of congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair on children. J Pediatr Surg 42: 657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Jeruss S, Terrin N, Tighiouart H, Wilson JM, Parsons SK. 2007b. Impact on family of survivors of congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: a pilot study. J Pediatr Surg 42: 1845–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonrod EM, Margraf RL, Russell A, Voelkerding KV, Reese MG. 2013. Clinical analysis of genome next-generation sequencing data using the Omicia platform. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 13: 529–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devictor D, Latour JM, Tissières P. 2008. Forgoing life-sustaining or death-prolonging therapy in the pediatric ICU. Pediatr Clin North Am 55: 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garros D, Rosychuk RJ, Cox PN. 2003. Circumstances surrounding end of life in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics 112: e371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer J, Ekici AB, Endele S, Popp B, Zweier C, Wiesenar A, Wohlleber E, Dufke A, Rossier E, Petsch C, et al. 2012. Haploinsufficiency of ARID1B, a member of the SWI/SNF-A chromatin remodeling complex, is a frequent cause of intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet 90: 565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ 2016. Exome Variant Server, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Retrieved 2016, from http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/.

- Karczewski KJ, Weisburd B, Thomas B, Solomonson M, Ruderfer DM, Kavanagh D, Hamamsy T, Lek M, Samocha KE, Cummings BB, et al. 2016. The ExAC browser: displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res 45: D840–D845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan SP, Busche KD, Chen LM, McCarthy L, Inman KJ, Sibbald WJ. 1997. A retrospective review of a large cohort of patients undergoing the process of withholding or withdrawal of life support. Crit Care Med 25: 1324–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler S, Vasilevsky NA, Engelstad M, Foster E, McMurry J, Aymé S, Baynam G, Bello SM, Boerkoel CF, Boycott KM, et al. 2017. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res 45: D865–D876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NA, Farrow EG, Gibson M, Willig LK, Twist G, Yoo B, Marrs T, Corder S, Krivohlavek L, Walter A, et al. 2015. A 26-hour system of highly sensitive whole genome sequencing for emergency management of genetic diseases. Genome Med 7: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval MV, Wang X, Reynolds M, Fischer AC. 2011. Costs of congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair in the United States—extracorporeal membrane oxygenation foots the bill. J Pediatr Surg 46: 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al. 2015. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17: 405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen GWE, Clayton-Smith J, ARID1B-CCS Consortium. 2014. The ARIB1B phenotype: what we have learned so far. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 166C: 276–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNOMED. 2016. SNOMED-CT Systematized Nomeclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms. http://www.ihtsdo.org/snomed-ct, from http://www.ihtsdo.org/snomed-ct.

- Stark Z, Behrsin J, Burgess T, Ritchie A, Yeung A, Tan TY, Brown NJ, Savarirayan R, Patel N. 2015. SNP microarray abnormalities in a cohort of 28 infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet Part A 167A: 2319–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurusaki Y, Okamoto N, Ohashi H, Kosho T, Imai Y, Hibi-Ko Y, Kaname T, Naritomi K, Kawame H, Wakui K, et al. 2012. Mutations affecting components of the SWI/SNF complex cause Coffin-Siris syndrome. Nat Genet 44: 376–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn J, Yu L, Chung WK. 2014. Genetic causes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 19: 324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Robinson PN, Wang K. 2015. Phenolyzer: phenotype-based prioritization of candidate genes for human diseases. Nat Methods 12: 841–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Sawle AD, Wynn J, Gudrun A, Stolar CJ, Arkovitz MS, Potoka D, Azarow KS, Mychaliska GB, Shen Y, et al. 2015. Increased burden of de novo predicted deleterious variants in complex congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum Mol Genet 24: 4764–4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweier M, Peippo MM, Pöyhönen M, Kääriäinen H, Begemann A, Joset P, Oneda B, Rauch A. 2017. The HHID syndrome of hypertrichosis, hyperkeratosis, abnormal corpus callosum, intellectual disability, and minor anomalies is caused by mutations in ARID1B. Am J Med Genet A 173: 1440–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.