Abstract

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is increasingly used clinically in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). However, rTMS treatment response can be slow. Early research suggests that accelerated forms of rTMS may be effective but no research has directly evaluated a schedule of accelerated rTMS compared to standard rTMS. To assess the efficacy of accelerated rTMS compared to standard daily rTMS., 115 outpatients with MDD received either accelerated rTMS (n = 58) (i.e., 63,000 high frequency rTMS pulses delivered as 3 treatments per day over 3 days in week 1, 3 treatments over 2 days in week 2 and 3 treatments on a single day in week 3) or standard rTMS (n = 57) (i.e., 63,000 total high frequency rTMS pulses delivered over 5 days per week for 4 weeks) following randomization. There were no significant differences in remission or response rates (p > 0.05 for all analyses) or reduction in depression scores (Time by group interaction (F (5, 489.452) = 1.711, p = 0.130) between the accelerated and standard rTMS treatment groups. Accelerated treatment was associated with a higher rate of reported treatment discomfort. It is feasible to provide accelerated rTMS treatment for outpatients with depression and this is likely to produce meaningful antidepressant effects.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is clearly a highly prevalent disorder and one in which there is a high rate of inadequate treatment response: it has been well established that approximately 30% of patients with MDD do not respond to standard medication and psychological therapies [1]. So-called treatment resistant depression (TRD) results in considerable suffering for individuals, as well as increased burden of care for family and increased treatment costs. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non-invasive means of stimulating nerve cells in superficial areas of the brain which has been intensively developed over the last 20 years as an antidepressant treatment. Studies using focal stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) for the treatment of depression have consistently shown positive results which have been summarized in numerous positive meta-analyses (e.g., refs. [2, 3] rTMS treatment is generally very well tolerated with a very low rate of treatment emergent side effects or adverse events [4]. This gives considerable scope to investigate the effects of increasing treatment dose (i.e., total number of pulses) or more intensive treatment schedules.

Despite the effectiveness of rTMS, one of its practical limitations is that clinical response is slow and treatment is cumbersome to administer. Most responders to rTMS take at least several weeks of daily treatment sessions to experience mood change, and substantial response often requires 4–6 weeks of treatment, requiring attendance at a treatment site on a daily basis (i.e., 5 days per week). In addition, the slow rate of response makes it not suitable for patients requiring rapid treatment efficacy for severe symptoms, particularly those with acute suicidal ideation or other urgent treatment needs.

Preliminary research suggests that a more rapid improvement in depressive symptoms may be achieved with accelerated rTMS protocols. In the first study of this type, Holtzheimer et al. provided 15-treatment sessions to patients over a single 2 day period with substantial antidepressant effects seen after the 2 days, which persisted at the three and six week follow-up [5]. In addition, a number of other studies have demonstrated that substantially higher doses of rTMS can be used without substantial side-effects emerging. For example, Hadley et al. provided up to 34,000 pulses per week and showed significant antidepressant effects with no significant adverse outcomes [6].

Recently, several additional studies have explored accelerated rTMS approaches. McGirr et al. provided rTMS twice daily over a 2 week period to 27 patients in an open label study and found a 37% remission and 56% response rate [7]. Baeken et al [8]. provided a more intensive accelerated protocol (5 sessions per day for 4 days) in a cross over sham controlled study design. Although the results of this study are somewhat hard to interpret due to the cross over nature of the design and a substantive placebo response rate, active treatment did appear to be associated with rapid antidepressant effects.

Despite the promising nature of these studies, no trials have been published to date that compare the outcomes achieved with an accelerated rTMS protocols to that seen with standard rTMS. Therefore, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to address this question. After several small pilot studies of differing accelerated protocols, we devised an approach consisting of 3 weeks of decreasing treatment intensity. In week 1, patients were provided 3 treatments per day over 3 days. In week 2, 3 treatments over 2 days were provided and in week 3, 3 treatments on a single day were provided. Each treatment day involved a total of 250 10 Hz trains so the total dose of TMS provided across 6 days was equal to that provided in 20 days of treatment at 75 trains per day. We chose fewer, higher dose, sessions each day rather than more lower dose sessions based on patient feedback from our pilot phase. We chose to stagger treatment at decreasing intensity over the 3 weeks as we observed a relatively high rate of early relapse in patients just treated within one week in this pilot phase as well. We hypothesized that the initial 3 days would produce antidepressant effects and that these effects would be consolidated and enhanced in the extra sessions in week 2 and 3. There was limited information on which to base the spacing between treatment sessions. Studies have started to explore the impact of spacing between multiple brain stimulation sessions [9] but to date none of this research has focused on the DLPFC. It is also notable that in this study, as in clinical rTMS research [10], there were clear patterns of differences in stimulation response and non-response between individuals.

Our primary hypothesis for the study was that treatment with an accelerated rTMS protocol would result in a more rapid reduction of depressive symptoms compared to a standard rTMS treatment approach, but that there would be no difference in overall efficacy between an accelerated and standard rTMS approach in the treatment of depression.

Methods

Study design

This study was a parallel design two arm single blind randomized controlled trial with randomization to accelerated or standard rTMS treatment schedule. Randomization occurred through the use of a single random number sequence. The clinician administering treatment was aware of the treatment group and the patient was aware of the treatment schedule. Symptom raters were blind to group. Patients were frequently counseled to avoid mentioning any information that would reveal the treatment schedule to the raters.

The conduct of the study was approved by the Alfred Hospital and Monash University Human Research and Ethics committees and the trial was registered with theAustralian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12613000044729). All participants were required to give written informed consent.

Participants

All participants had a diagnosis of MDD as confirmed by the study psychiatrist and the conduct of a Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [11]. Participants were recruited by referrals from both public and private psychiatrists. Patients were required to have moderate to severe depression as defined by a Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score of >19, and have TRD at Stage II of the Thase and Rush classification [1]. This requires failure to respond to adequate courses of two different antidepressants. Patients were excluded if they had a contraindication to TMS (such as the presence of metallic implants in the head, cardiac pacemakers, cochlear implants, or other implanted electronic devices), had initiated a new antidepressant treatment in the preceding 4 weeks (or changed medication dose), were found to have another Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Axis I psychiatric disorder (except an anxiety disorder), had a history of substance abuse or dependence during the last 6 months, were pregnant, or had a past history of stroke, neurodegenerative disorder or other major neurological illness. Medication doses were kept unchanged during the trial.

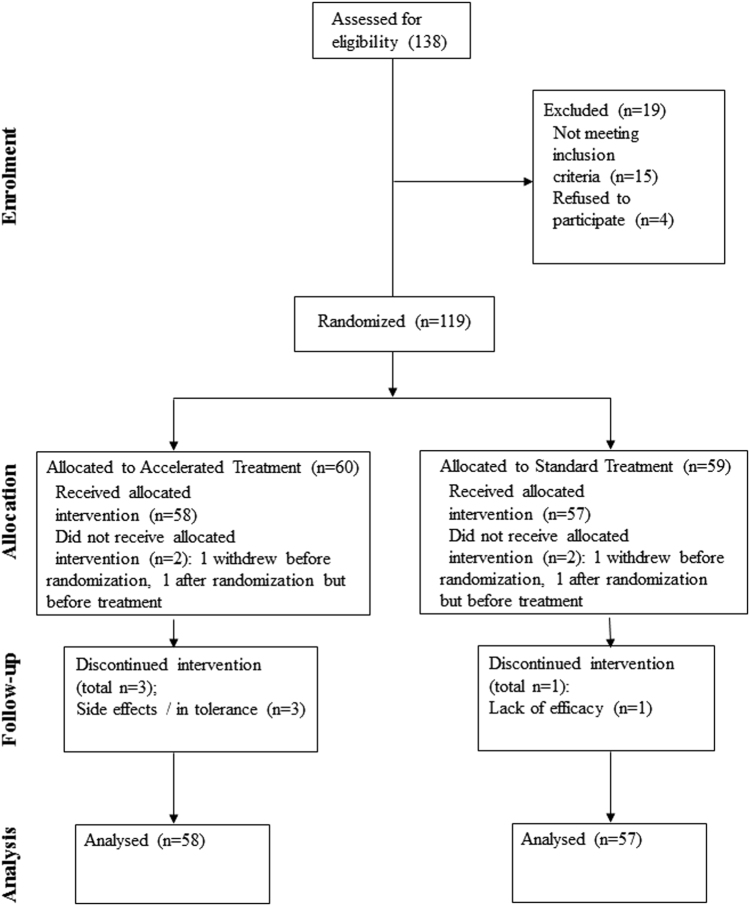

The planned sample size was 120 subjects (60 per group). With a conservative pre-treatment withdrawal rate of 8%, this would produce a sample size of a minimum of 110 subjects for an intention-to-treat analysis. This sample size would provide greater than 80% power to detect a greater than four point difference between the two groups on the primary outcome measure assuming a standard deviation of 7.5. Of 138 patients assessed for eligibility 119 were randomized, see Consort Flowchart for details (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram for study

Clinical measures

Demographic variables and potential co-variates were recorded at baseline following a clinical interview. DSM-IV diagnosis was assessed with the MINI. To investigate the time course of clinical effects, we assessed patients with the MADRS [12] at baseline and at the end of weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8. Patients were assessed at the same time points with the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI) [13] and the Scale of Suicidal Ideation (SSI). The CORE rating of melancholia [14] was used at baseline. Response on the HDRS-17 and MADRS scales was defined as a greater than 50% reduction in scores. Remission was defined as a score of less than 8 on the HDRS or less than 10 on the MADRS [15]. Cognitive tests were conducted at baseline and after the last treatment and included assessment of attention, speed of information processing, verbal and visual memory, and executive function. Specifically, the battery consisted of the Digit Span [16], Digit Symbol Coding [16], Trail Making Test [17], Rey Verbal Auditory Learning Test [18], Stroop [19], Verbal Fluency [20], Brief Visuospatial Memory Test [21], and the Rey Complex Figure [22]. The Wechsler Test of Adult Reading was done at baseline as an estimate of premorbid ability [23].

TMS treatment

Patients received one of two treatment conditions:

1. Accelerated rTMS treatment: In week 1, patients were provided 3 treatments per day over 3 days. In week 2, 3 treatments over 2 days were provided and in week 3, 3 treatments on a single day were provided. In the three treatment sessions each day we provided 83, 83, and 84 trains respectively of 10 Hz rTMS to the left DLPFC. 4.2 sec trains were applied at 120% of the resting motor threshold with a 15 s inter-train interval (10,500 pulses per day across the three sessions, 63,000 pulses in total). Sessions were provided 15–30 min apart.

2. Daily treatment: In 20 daily sessions provided 5 days per week over 4 weeks each treatment involved the provision of 75 trains of 10 Hz rTMS to the left DLPFC. 4.2 s trains were applied at 120% of the resting motor threshold with a 25 s inter-train interval (3150 pulses per day, 63,000 pulses in total).

Stimulation localization followed standard procedures. First, the site for the optimal activation of the abductor pollicis brevis (APB) muscle in the contralateral hand was located whilst stimulating the relevant motor cortical region at supra-threshold intensity. This site was marked on the scalp. We then measured 6 cm anteriorly on the scalp surface.

Data analysis

T tests and χ2 tests were used to investigate differences between the groups on demographic and baseline clinical variables. The primary analysis was based on remission and response rates on HDRS and MADRS data at week 4 (HDRS and MADRS) and week 8 (MADRS) using χ2 tests. Linear mixed model analyses were then calculated for the dependent measures (HAMD, MADRS, BDI, and SSI) with fixed effects of group and time. An autoregressive first order (AR(1)) covariance structure was determined to provide an appropriate fit for the data and restricted maximum likelihood (REML) was used to estimate parameters. Post hoc pairwise comparisons between groups at each time point and within groups comparing time points were calculated for the MADRS data with Bonferroni correction. In addition, we compared the distribution of response between the two groups by plotting separately a kernel density estimation. We then compared outcomes in the responders to the 2 treatment arms using a definition of response of a 35% improvement from baseline to week 8 on the MADRS.

To investigate cognitive outcomes of treatment, baseline to end of treatment change scores were calculated and compared between the two groups with independent samples T-test. Paired sample T-tests were used to look for changes in cognitive performance from baseline to end of treatment within the two treatment groups. Independent sample T-tests and χ2 tests were also used to compare responders to non-responders on a range of clinical and demographic variables. All procedures were two-tailed and unless otherwise stated, significance was set at an α level of 0.05. All statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS 22.0 (SPSS for Windows. 10.0 Chicago: SPSS; 2013).

Results

Participants

One hundred and nineteen patients were recruited and consented (Fig. 1). Two subjects withdrew during the baseline assessment process, prior to randomization, and treatment. Two subjects were randomized but withdrew prior to commencing treatment (one due to obtaining new employment, one due to physical illness). Therefore, 115 patients (66 female/49 male, mean age = 49.0 ± 13.8 years) entered treatment and are included in the analysis (see Table 1). Of these, 111 completed baseline and at least week 4 assessments. There were four withdrawals, three in the accelerated treatment group (two due to treatment discomfort, one due to worsening of migraine) and one (failure of efficacy) in the standard group. There were no differences in the baseline severity of scores on any of the rating scales or in any demographic or clinical variables between the groups.

Table 1.

Patient clinical and demographic data

| Accelerated group | Standard Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Frequency | SD | Mean/Frequency | SD | |

| Age | 48.2 | 14.4 | 49.9 | 13.3 |

| Sex (M/F) | 25/33 | 24/33 | ||

| Handedness (R/L/Ambidextrous) | 52/3/3 | 45/8/3 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||

| MDD–single episode | 26 | 17 | ||

| MDD–relapse | 31 | 39 | ||

| BPAD (Y/N) | 8/49 | 8/47 | ||

| Duration of Illness (years) | 19.8 | 13.2 | 21.2 | 13.1 |

| Age of onset (years) | 26.3 | 12.8 | 27.9 | 14.4 |

| Number of depressive episodes | 3.2 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 8.0 |

| Length of current depressive episode (years) | 10.0 | 12.8 | 8.2 | 10.2 |

| Number of past medication trials | 10.7 | 19.6 | 8.6 | 13.8 |

| Previous ECT (Y/N) | 7/51 | 8/49 | ||

| ECT this episode | 5/53 | 6/51 | ||

| CORE total | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| HDRS | 23.0 | 4.1 | 23.3 | 4.5 |

| MADRS | 31.3 | 5.3 | 31.6 | 5.4 |

| BDI | 36.3 | 8.2 | 34.8 | 10.1 |

| SSI | 3.6 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 6.3 |

There were no significant differences across the groups on any variables

MDD major depressive disorder, BPAD bipolar affective disorder, HRSD Hamilton depression rating scale, MADRS Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale, BDI Beck depression inventory, SSI scale of suicidal ideation

Primary outcome

Response and remission rates at the end of the 4 week treatment period on the HDRS (and at week 4 and week 8 on the MADRS) are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in response rates or remission rates between the groups in any of the analyses.

Table 2.

Treatment response and remission rates

| Group | Response | Remission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAMD | Week 4 | Accelerated | 20.3% | 11.9% |

| Standard | 29.8% | 17.5% | ||

| χ 2 | 1.4, p = 0.24 | 0.75, p = 0.39 | ||

| MADRS | Week 4 | Accelerated | 23.7% | 15.3% |

| Standard | 33.3% | 12.3% | ||

| χ 2 | 1.4, p = 0.25 | 0.21, p = 0.64 | ||

| Week 8 | Accelerated | 25.4% | 16.9% | |

| Standard | 29.8% | 17.5% | ||

| χ 2 | 0.28, p = 0.60 | 0.01, p = 0.93 |

Response defined as a > 50% reduction in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) and Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) scores. Remission defined as a HDRS score of <8 or MADRS score of <10

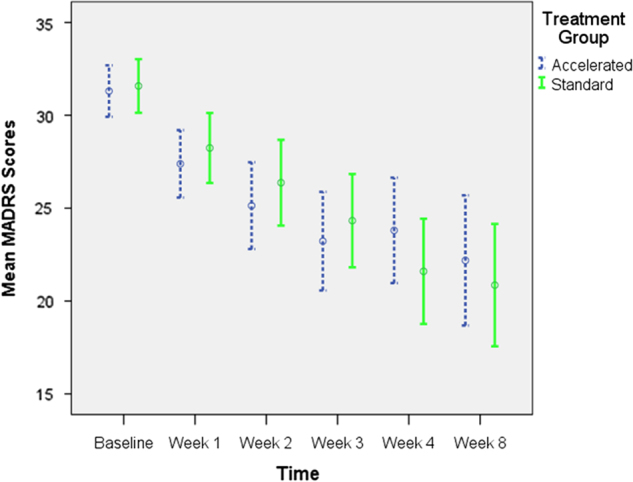

Secondary outcomes: change over time in depression severity

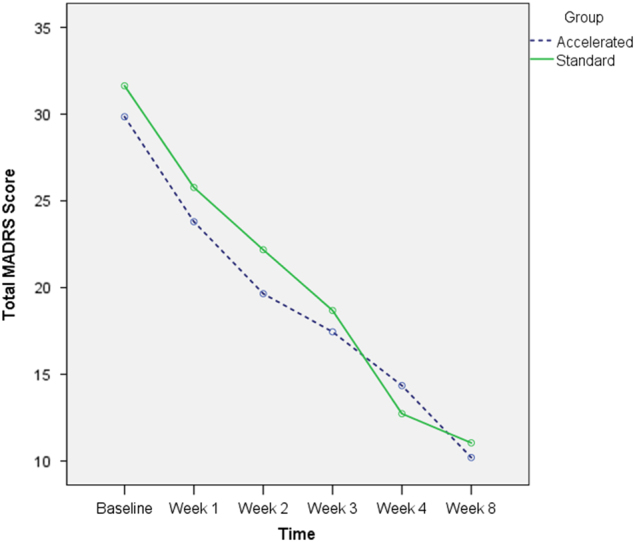

There was no difference in change in the MADRS scores between the groups between baseline and the week 8 assessment time point (Table 3; Fig. 2): There was a significant main effect of Time (F (5489.452) = 24.415, p > 0.000). There was no effect of treatment group (F (1126.891) = 0.001, p = 0.979), nor a significant time by group interaction (F (5489.452) = 1.711, p = 0.130).

Table 3.

Treatment response

| Baseline | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 8 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MADRS | Accelerated | Mean | 31.3 | 27.4 | 25.1 | 23.2 | 23.8 | 22.2 |

| SD | 5.3 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 9.2 | 10.6 | 12.1 | ||

| Standard | Mean | 31.6 | 28.2 | 26.4 | 24.3 | 21.6 | 20.9 | |

| SD | 5.4 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 10.5 | 10.6 | ||

| BDI | Accelerated | Mean | 36.2 | 26.6 | 25.6 | 23.5 | 23.8 | 23.5 |

| SD | 8.1 | 11.3 | 12.5 | 13.0 | 14.6 | 15.0 | ||

| Standard | Mean | 34.8 | 27.8 | 24.9 | 22.4 | 20.1 | 19.4 | |

| SD | 10.1 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 12.6 | 11.9 | ||

| SSI | Accelerated | Mean | 3.8 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

| SD | 5.9 | 7.2 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 2.2 | ||

| Standard | Mean | 4.2 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.2 | |

| SD | 6.3 | 7.3 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 4.0 | ||

| HDRS | Accelerated | Mean | 23.0 | 17.6 | ||||

| SD | 4.1 | 7.1 | ||||||

| Standard | Mean | 23.3 | 15.8 | |||||

| SD | 4.5 | 7.7 |

MADRS mean montgomery asberg depression rating scale, BDI Beck depression inventory, SSI scale of suicidal ideation, HDRS Hamilton depression rating scores for each study visit

Fig. 2.

Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) scores across study timepoints

Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed no differences in MADRS scores between the two groups at any of the time points. There were significant reductions in MADRS scores for the accelerate group from baseline to week 1 (p < 0.001), week 1 to week 2 (p < 0.05) but not the other time-points. For the standard group the between assessment reductions were significantly different from baseline to week 1 (p < 0.001) and weeks 3 and 4 (p < 0.01).

For the HDRS, no difference was seen in clinical outcomes: There was a significant main effect of Time (F (1111.757) = 95.680, p > 0.000). There was no effect of treatment group (F (1113.559) = 0.510, p = 0.477), nor a significant time by group interaction (F (1111.757) = 2.530, p = 0.115).

No differences across time were also seen in the other rating scale scores. For the BDI, there was a significant main effect of time (F (5428.550) = 5.652, p = 0.022), no effect of group (F (1134.263) = 0.173, p = 0.678), nor a significant time by group interaction (F (5428.550) = 0.157, p = 0.978). For the SSI, there was also a significant main effect of Time (F (5428.550) = 2.652 p = 0.022). There was no effect of treatment group (F (1131.454) = 0.173, p = 0.678), nor a significant time by group interaction (F (5428.550) = 0.157, p = 0.978).

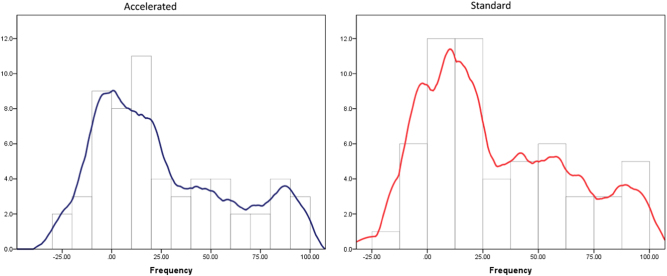

Responder analysis

As can be seen in Fig. 3, there was no substantive difference in the pattern of response between the two treatment groups. When we compared outcomes just for the responder group, there was no overall difference in degree or pattern of response (see Fig. 4). There was a significant main effect of Time (F (5184.027) = 44.696, p > 0.000). There was no effect of treatment group (F (152.934) = 0.647, p = 0.425), nor a significant time by group interaction (F (5184.027) = 1.066, p = 0.381). There were significant reductions in MADRS scores for the accelerate group from baseline to week 1 (p < 0.000), week 1 to week 2 (p = 0.01), week 4 to week 8 (p = 0.015). For the standard group the between assessment reductions were significant different from baseline to week 1 (p < 0.001), week 1 to week 2 (p = 0.021), week 2 to week 3 (p = 0.027) and weeks 3 to 4 (p < 0.00).

Fig. 3.

The distribution of response (change in Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) scores from baseline to 8 week follow-up for the two treatment groups

Fig. 4.

Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) scores across study timepoints for the responders only (defined as a greater than 35% reduction in MADRS scores from baseline to week 8)

Cognition

There were no between group differences in the change scores from baseline to end of treatment on any of the cognitive variables. There was significantly improved performance on the trail making test (A (p = 0.002) and B (p = 0.009)) in the accelerated group and in digital symbol coding in the standard treatment group (p = 0.007). No impairment in cognitive performance on any test in either group was seen.

Safety and tolerability

There were no serious adverse events in either treatment group. Eleven patients reported site discomfort during treatment in the accelerated group and two in the standard group (χ2 = 6.7, p = 0.01). Sixteen patients reported headaches following at least one treatment session in the accelerated and nine in the standard group (χ2. = 2.2, p = 0.14). Headaches were resolved in most cases within 2 h following treatment sessions.

Predictors of response

For the group as a whole there was no relationship between response to treatment and any of the demographic or clinical variables including age, sex, handedness, baseline illness severity, or any characteristics of the history of depression except for the following: (a) the CORE retardation subscale scores were significantly higher in non-responders than responders (0.68 ± 1.3 compared to 0.19 ± 0.5, p = 0.006), (b) a significantly greater percentage of patients who were non-responders were taking no current antidepressant medication (27.1%) compared to patients who responded to treatment (6.9%) (χ2 = 5.1, p = 0.02).

Discussion

This represents one of the first studies to directly compare clinical responses to accelerated and standard rTMS treatment. We found significant evidence of efficacy for the accelerated treatment approach that was comparable to standard rTMS treatment across all of the outcome variables. Despite providing a very high dose of daily treatment (250 trains of stimulation per day over three sessions), accelerated treatment was not associated with any serious adverse events. There was a higher rate of side-effects, especially the experience of site discomfort in the accelerated treatment group and a slightly higher rate of treatment discontinuation. Accelerated treatment was not associated with the development of any impairment in cognitive performance.

The most significant finding of this study is that an antidepressant response comparable to that seen with standard rTMS appears achievable with an accelerated stimulation format. We found no differences in overall clinical response, importantly including at the follow up assessment; which was 1 month after the end of the acute treatment phase (and in the case of the accelerated group more than five weeks after the end of treatment). Interestingly, although there was no difference in overall response rates, there did appear to be some difference in the pattern of change in depressive symptoms. Patients in the accelerated group demonstrated significant reductions in depression severity in the first two weeks of treatment when they received most of their treatment sessions, whereas significant improvements in depression were seen in the standard group in the first and fourth weeks of therapy. We did not see a significant difference in depression severity at week one or two, but the above finding suggests that there may be more rapid improvement in symptoms with this form of accelerated treatment application.

There was a trend towards greater response and remission rates in the standard treatment group across all of the dichotomous outcome assessment time points and a difference that, although not significant, appeared meaningful at week 4 (~9% in response rates on the HDRS-17). However, none of these differences reached statistical significance and it is important to note that the numerical advantage of standard treatment was much less at the week 8 time point, the clinically most relevant assessment. In fact, a sample size calculation based upon the difference in response rate at eight weeks on the MADRS found that a sample of over 3200 subjects would be required to establish that this degree of difference is statistically significant with a power of 0.8 (alpha of 0.05). There was also no substantial numerical difference in remission rates at eight weeks.

The stimulation settings and course of treatment applied warrants comment. We chose to compare accelerated treatment to a four-week course of rTMS. However, it is notable that some of the larger rTMS studies have applied treatment over longer periods of time (for example for six weeks [24] and it is possible that a longer period of standard treatment would result in a greater overall therapeutic response than the accelerated protocol applied in our study. However, as a wide range of studies have demonstrated antidepressant efficacy of rTMS when applied for four weeks and most importantly we chose this duration of standard treatment to allow for matching of the total pulse number applied between the two treatment groups. Although a longer course of standard treatment may produce greater therapeutic effects, it is also possible that we would get greater therapeutic effects if the accelerated treatment dose was increased or booster sessions were applied, for example on a weekly basis over a longer period of time.

Perhaps not surprisingly, there was some suggestion of greater problems with tolerability of the accelerated treatment. There was a significantly greater rate of report of site discomfort and a non-significantly greater rate of reported headaches with treatment. There were also several discontinuations in the accelerated group due to reported discomfort. However, it is noteworthy that the overall rates of treatment discontinuation were still very low (5% in the accelerated group and <4% overall) and most reported side effects were transient in nature. Importantly, accelerated treatment was not associated with any serious adverse events. This was despite us reducing the inter-train interval in the accelerated group from a standard 25 seconds to a 15 second duration. Anecdotally, patients were very happy to receive treatment in the accelerated manner especially due to the reduction in attendance required to obtain treatment.

Although patients were not blind to treatment group, we went to considerable lengths to ensure that the raters undertaking depression severity assessments were unaware of treatment group. Patients were counselled not to reveal details of their treatment schedules or experiences to raters at the start of treatment and repeatedly reminded of this by the TMS treaters before each assessment. Assessment and treatment schedules were organized and monitored to minimize the likelihood that assessors would be un-blinded through incidental contact with patients, for example in waiting rooms. However, it is possible that treatment assessments might have been inadvertently influenced by inadequacy of blinding of the assessors and we do not have systematic data to rule this out.

Although rTMS studies have clearly shown that this treatment does not have adverse impacts on cognitive performance of patients undergoing treatment (for example ref. [24, 25]) and that in contrast that it might produce subtle improvements in cognitive performance [26, 27], we felt that it was important to include an assessment of cognitive performance due to the intensive nature of our treatment schedule in the accelerated group. Importantly, accelerated treatment was not associated with any impairments in cognitive function and showed a similar pattern of improvement in limited cognitive domains that has been seen in other research: interestingly the improvement in performance on the trail-making task seen with accelerated treatment here has recently been shown to be the most consistently demonstrated improvement in cognitive performance in rTMS studies in depression [28].

A large multi-site comparative trial would clearly be the gold standard in establishing the therapeutic equivalence of accelerated and standard forms of rTMS. Ideally, patients would be randomized to both one active and one sham condition concurrently to truly allow a randomized blinded comparison. For example, patients would attend every day and receive either active accelerated and sham standard or sham accelerated and active standard forms of treatment. However, conducting a study of this nature is likely to be logistically and scientifically challenging. No sham coil systems have been demonstrated to sufficiently mimic the experience of active rTMS treatment so that they could successfully maintain blinding in patients concurrently receiving courses of both active and sham stimulation: this may well be possible but would require systematic demonstration of the successful capacity of any new system to maintain blinding. It would also be difficult to engage patients in a protocol like this whereon multiple days they would be undergoing four lengthy stimulation sessions (three accelerated and one standard). In this context, the type of study design we have used may be close to the most rigorous approach that can be applied to this question.

It is worthy of note, that although the accelerated treatment did produce meaningful clinical benefits, the application of this type of treatment schedule in a clinical setting is likely to be somewhat difficult. The provision of three treatment sessions resulted in patients being in the clinic setting for 2–2½ h on each accelerated treatment day. This was generally an acceptable compromise for patients but caused significant scheduling problems fitting this around other daily treatment schedules. It is also notable that our overall response rate was somewhat lower than has been seen in a number of other open label studies, including several of our own (for example ref [29]). It is possible that this relates to the duration of treatment provided in this study which was limited to 63,000 pulses/four weeks in the standard group. This is shorter than is provided in many settings in clinical practice where TMS protocols often extend to 6 weeks or beyond and may well have played a significant role.

As discussed above, the lack of blinding of patients in a protocol is the main limitation of our capacity to generalize from the results of this study. The sample size, although substantial, is also a limitation of the study. This was an obtainable single site sample to demonstrate the value of this form of accelerated treatment approach but we clearly only had power to demonstrate relatively large differences in clinical outcomes between the two treatment arms. A more substantive study, presumably to be conducted on a multi-site basis, is clearly required to definitively demonstrate the equivalent efficacy of accelerated to standard forms of rTMS or to demonstrate its clinical inferiority.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that rTMS treatment for depression can be successfully provided in an accelerated treatment format. The schedule that we used, with treatment on three, 2 and 1 day per week across three weeks, produced antidepressant effects that were similar to, if not equivalent to those seen with a standard four-week course of rTMS. Accelerated rTMS was associated with a higher rate of treatment discomfort but still resulted in a low overall discontinuation rate. A definitive multisite trial is justified to demonstrate whether this form of treatment could be adopted more widely in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

PBF is supported by a Practitioner Fellowship grant from National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (1078567). KEH is supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1082894). ZJD was supported by the Ontario Mental Health Foundation (OMHF), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and the Temerty Family and Grant Family and through the Center for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) Foundation and the Campbell Institute. Funding for this study was provided by an NHMRC project grant (1041890).

Conflict of interest

In the last 3 years PBF has received equipment for research from Magventure A/S, Medtronic Ltd, Neurosoft and Brainsway Ltd. He has served on a scientific advisory board for Bionomics Ltd and LivaNova. In the last 3 years, ZJD has received research and equipment in-kind support for an investigator-initiated study through Brainsway Inc and Magventure Inc. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1996;19:179–200. doi: 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schutter DJ. Antidepressant efficacy of high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in double-blind sham-controlled designs: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2009;39:65–75. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slotema CW, Blom JD, Hoek HW, Sommer IE. Should we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatment methods to include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)? A meta-analysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:873–84. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04872gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual-Leone A. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:2008–39. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holtzheimer PE, 3rd, McDonald WM, Mufti M, Kelley ME, Quinn S, Corso G, et al. Accelerated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:960–3. doi: 10.1002/da.20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadley D, Anderson BS, Borckardt JJ, Arana A, Li X, Nahas Z, et al. Safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of high doses of adjunctive daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression in a clinical setting. J ECT. 2011;27:18–25. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181ce1a8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGirr A, Van den Eynde F, Tovar-Perdomo S, Fleck MP, Berlim MT. Effectiveness and acceptability of accelerated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: an open label trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:216–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baeken C, Vanderhasselt MA, Remue J, Herremans S, Vanderbruggen N, Zeeuws D, et al. Intensive HF-rTMS treatment in refractory medication-resistant unipolar depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2013;151:625–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nettekoven C, Volz LJ, Leimbach M, Pool EM, Rehme AK, Eickhoff SB, et al. Inter-individual variability in cortical excitability and motor network connectivity following multiple blocks of rTMS. Neuroimage. 2015;118:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE, Anderson RJ, Daskalakis ZJ. A study of the pattern of response to rTMS treatment in depression. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:746–53. doi: 10.1002/da.22503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Hickie I, Brodaty H, Boyce P, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K, et al. Inter-rater reliability of a refined index of melancholia: the CORE system. J Affect Disord. 1993;27:155–62. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawley CJ, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T, Hertfordshire Neuroscience Research g. Defining remission by cut off score on the MADRS: selecting the optimal value. J Affect Disord. 2002;72:177–84. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00451-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wechsler D. Wechsler memory scale—third edition. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Partington J. Trail making test. Psychol Serv Cent Bull. 1949;1:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt M. Rey auditory verbal learning test: RAVLT a handbook. Western Psychological Services; 1996. Los Angeles (CA)

- 19.Golden C. Stroop colour and word test: a manual for clinical and experimental use. Skoelting: Chicago; 1978.

- 20.Benton A, Hamsher K. Multilingual aphasia examination. Iowa City; 1976. University of Iowa Press

- 21.Benedict R. Brief visuospatial memory test-revised. San Antonio: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyers J. The Meyers scoring system for the rey complex figure and the recognition trial: professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wechsler D. Wechsler test of adult reading. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, Sampson S, Isenberg KE, Nahas Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1208–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzgerald PB, Brown T, Marston NAU, Daskalakis ZJ, Kulkarni J. A double-blind placebo controlled trial of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1002–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoy KE, Segrave RA, Daskalakis ZJ, Fitzgerald PB. Investigating the relationship between cognitive change and antidepressant response following rTMS: a large scale retrospective study. Brain Stimul. 2012;5:539–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serafini G, Pompili M, Belvederi Murri M, Respino M, Ghio L, Girardi P, et al. The effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cognitive performance in treatment-resistant depression. A systematic review. Neuropsychobiology. 2015;71:125–39. doi: 10.1159/000381351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin DM, McClintock SM, Forster JJ, Lo TY, Loo CK. Cognitive enhancing effects of rTMS administered to the prefrontal cortex in patients with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual task effects. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34:1029–1039. doi: 10.1002/da.22658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzgerald PB, Hoy K, Gunewardene R, Slack C, Ibrahim S, Bailey M, et al. A randomized trial of unilateral and bilateral prefrontal cortex transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment-resistant major depression. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1187–96. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]