Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have important roles in regulating stress-response genes in plants. However, identification of miRNAs and the corresponding target genes that are induced in response to cadmium (Cd) stress in Brassica napus remains limited. In the current study, we sequenced three small-RNA libraries from B. napus after 0 days, 1 days, and 3 days of Cd treatment. In total, 44 known miRNAs (belonging to 27 families) and 103 novel miRNAs were identified. A comprehensive analysis of miRNA expression profiles found 39 differentially expressed miRNAs between control and Cd-treated plants; 13 differentially expressed miRNAs were confirmed by qRT-PCR. Characterization of the corresponding target genes indicated functions in processes including transcription factor regulation, biotic stress response, ion homeostasis, and secondary metabolism. Furthermore, we propose a hypothetical model of the Cd-response mechanism in B. napus. Combined with qRT-PCR confirmation, our data suggested that miRNAs were involved in the regulations of TFs, biotic stress defense, ion homeostasis and secondary metabolism synthesis to respond Cd stress in B. napus.

Keywords: miRNAs, cadmium stress, gene regulation, Brassica napus

1. Introduction

Increasing heavy metal pollution in aquatic and terrestrial environments, caused in part from the burning of fossil fuels and mining, has drawn worldwide attention [1]. Of the seven key heavy metal pollutants, cadmium (Cd) is one of the most harmful to both ecosystems and human health [2,3]. Although Cd ions (Cd2+) are not essential for plants, they are taken in easily by roots and then transported to the above-ground organs [4]. Excess Cd accumulation can cause detrimental effects on plant growth and development, including inhibition of photosynthetic activity [5], membrane distortion [6], stunted plant growth [7,8], decreased nutrient uptake [9], and decreased crop yield [4,10]. To tolerate Cd stress, plants have evolved elaborate protective mechanisms and extensive research has begun to reveal these mechanisms [11,12]. For example, AtPDR8 (PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE 8, an ABC transporter) acts as a Cd2+ efflux pump in the plasma membrane of Arabidopsis cells [13]. The Zn/Cd transporters HMA4 (P-type ATPase) in Arabidopsis halleri and HMA3 (ATPase) in Thlaspi caerulescens were reported to be involved in Cd regulation [14]. In tobacco (Nicotiana spp.), over-expression of OsACA6 resulted in improved Cd2+ stress tolerance by maintaining cellular ion homeostasis and regulating the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging pathway [15]. In addition, heavy metal stress signals induced through various pathways have been identified; these include mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [16], hormones (e.g., salicylic acid) [17], Ca-calmodulin system [18], ROS signaling [19], and corresponding transcription factors (TFs) [20,21].

Though studies of the mechanisms on physiological and biochemical levels have been conducted [22], the regulatory mechanisms in response to Cd2+ stress on genetics, transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels are still vague. To explore the mechanisms regulating the response to Cd2+ stress, scientists have identified Cd-responsive genes and characterized their regulatory networks. Cd-responsive TFs have been identified in Arabidopsis [23], pea (Pisum spp.) [19] and barley (Hordeum spp.) [24], including WRKY53 [25], basic leucine zipper (bZIP) [26], myeloblastosis protein 4, 48 and 124 (MYB4, 48 and 124) [20,23], and ethylene-responsive factor 1/2 (ERF1/2) [23]. These Cd-responsive TFs are essential for regulating the expression of genes associated with the Cd stress response.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of miRNAs in many biological processes including organ development, signal transduction, as well as biotic and abiotic stress responses at post-transcriptional levels. Moreover, miRNAs were identified as key roles in heavy metal regulatory networks. For example, nineteen Cd-responsive miRNAs in rice (Oryza spp.) have been identified using microarrays [27]. Furthermore, 39 known and 8 novel miRNAs were differentially expressed in response to Cd treatment in rice [28]. A recent study with radish (Raphanus spp.) identified 23 Cd-responsive miRNAs and characterized the corresponding targets associated with metal transport and signaling [29]. In Typha angustifolia, 155 miRNAs (114 conserved and 41 novel miRNAs) were screened after Cd exposure [1]. All of these evidences strongly support the key roles of miRNAs in heavy metal stress responses at the post-transcriptional level.

Oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) is a globally important economic crop due to its seed oil, which is used for food and biofuel. Several studies have been conducted to understand the physiological responses of B. napus to Cd stress [22,30,31,32,33]. Recently, a genome-wide identification of miRNAs involved in agronomic traits, abiotic stress, biotic stress, and oil content in B. napus was performed [34,35,36,37]. Furthermore, several Cd2+ stress responsive miRNAs have been reported and related regulatory mechanisms have also been discussed [38,39,40]. Noteably, miR395 and corresponding targets (BnSultr2;1, BnAPS3 and BnAPS4) were identified as key roles in the heavy metal stress [39]. In another study, 802 target genes for 37 miRNA families were also screened as regulators in response to Cd stress [40]. Even though many miRNAs in B. napus have been revealed using high-throughput sequencing technology, heavy metal-regulated miRNAs (especially those related to Cd2+ stress) and corresponding target genes have not been entirely identified. Thus, identifying and characterizing the miRNAs involved in a Cd2+ stress response in B. napus may be useful for understanding the mechanisms of heavy metal tolerance.

In the present study, genome-wide identification of miRNAs in response to Cd stress was conducted in B. napus using high-throughput sequencing technology. In total, 44 known and 103 novel miRNAs were identified and 39 miRNAs were differentially expressed. Additionally, an integrated schematic diagram was created based on differentially expressed miRNAs and corresponding target genes to better understand the regulation mechanisms related to Cd stress tolerance. These results extend our knowledge of miRNA-guided regulation of heavy metal stress responses in B. napus.

2. Results

2.1. High-Throughput Sequencing of Small RNAs

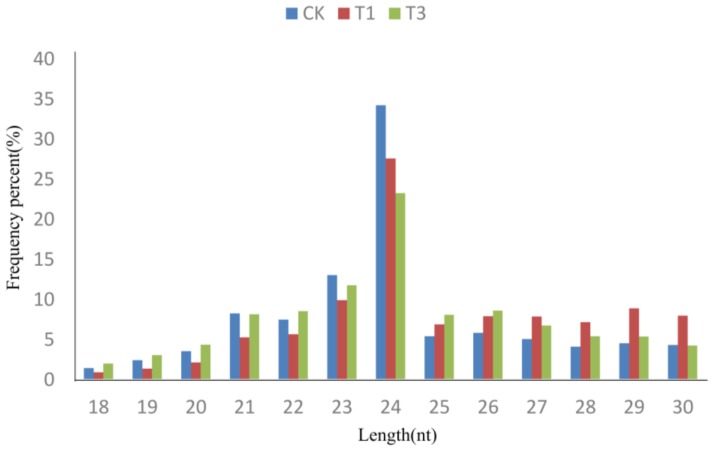

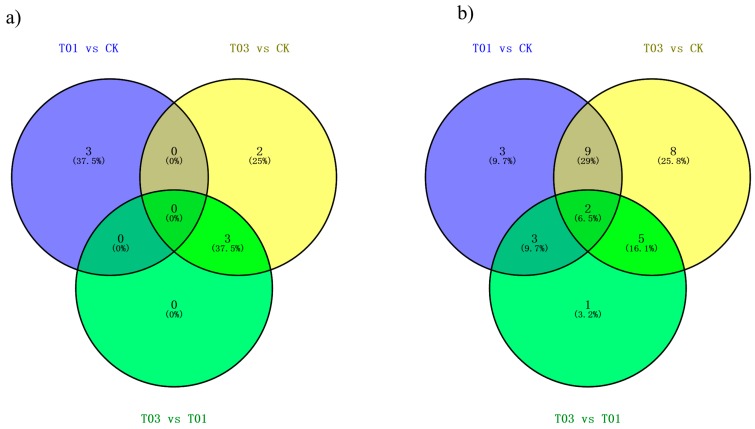

Three sRNA libraries were generated and sequenced using Illumina sequencing technology. High-throughput sequencing generated 16,892,251 reads in the CK library, 20,019,156 reads in the T01 library, and 19,891,839 reads in the T03 library. After removing adaptors, contamination and sequence lengths greater than 30 or less than 18, a total of 13,800,597 clean reads were obtained for CK, 13,920,988 for T01, and 15,802,302 for T03 (Table 1). The proportions of common and specific small RNAs were further analyzed between pairs of libraries. For total small RNAs, 59.44, 60.62% and 62.95% were common detected in CK and T1, CK and T3, and T1 and T3, respectively; 18.29–21.01% were specific detected in CK, T1 and T3 library (Figure 1a). However, for unique small RNAs, 9.40–9.91% were common detected in CK and T1, CK and T3, and T1 and T3 comparisons and 43.03–47.31% were specific detected in three samples (Figure 1b). The size distribution of all sRNAs (18–30 nt) was uneven, the 24-nt classes showed the highest degree of redundancy in all three libraries (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of sequencing reads in three sRNA libraries in B. napus.

| Samples | Raw_Reads | Low_Quality | containing’n’reads | Length < 18 | Length > 30 | Clean_Reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 16,892,251 | 0 | 1164 | 575,989 | 2,514,501 | 13,800,597 |

| T1 | 20,019,156 | 0 | 1413 | 799,829 | 5,296,926 | 13,920,988 |

| T3 | 19,891,839 | 0 | 1417 | 1,122,546 | 2,965,574 | 15,802,302 |

Figure 1.

Venn diagrams for analysis of total (a) and unique (b) reads between each of the two samples of B. napus.

Figure 2.

Length distribution of small RNAs in three samples. Y-axis: the percentage of small RNA reads.

2.2. Identification of Known and Novel miRNAs in B. napus

In general, miRNAs are highly conserved among species. The miRBase database (v21.0, http://www.mirbase.org/index.shtml) [41,42], which contains 92 mature miRNAs for B. napus, was used to detect known miRNAs with no more than two mismatches in the three libraries generated for the current work. A total of 44 known B. napus miRNAs, belonging to 27 families, were identified in this study (Table 2). Of these families, 18 families were identified containing one miRNA, 6 families containing more than three miRNAs, and 3 families containing two miRNAs (miR164, miR166 and miR395) (Table 2). In addition, 35 out of 44 miRNAs had a length of 21 nt, whereas 3, 5 and 1 miRNAs had lengths of 20 nt, 23 nt and 24 nt, respectively (Table 2). Furthermore, miR169g and miR211c were CK-specific, miR399a was T01-specific, and miR2111a-5p was T03-specific. All other miRNAs were commonly detected in the three libraries (Table 2).

Table 2.

Known miRNA families and their transcript abundance in the three samples.

| miRNA | Length | CK | T1 | T3 | Mature Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR1140 | 21 | 99.84 | 44.49 | 88.45 | ACAGCCTAAACCAATCGGAGC |

| miR156a | 21 | 25,154.03 | 16,041.64 | 13,758.44 | TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCACA |

| miR156b | 21 | 17,575.97 | 17,616.44 | 24,364.75 | TTGACAGAAGATAGAGAGCAC |

| miR156d | 20 | 25,634.20 | 16,450.91 | 14,216.79 | TGACAGAAGAGAGTGAGCAC |

| miR159 | 21 | 283,188.49 | 271,657.99 | 306,215.83 | TTTGGATTGAAGGGAGCTCTA |

| miR160a | 21 | 2976.08 | 1975.18 | 3031.52 | TGCCTGGCTCCCTGTATGCCA |

| miR161 | 21 | 57.05 | 53.38 | 152.78 | TCAATGCACTGAAAGTGACTA |

| miR164a | 21 | 2362.80 | 2411.14 | 2621.42 | TGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGTGCA |

| miR164b | 21 | 969.84 | 898.62 | 1045.35 | TGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGTGCG |

| miR166a | 21 | 100,777.77 | 105,636.37 | 92,513.67 | TCGGACCAGGCTTCATTCCCC |

| miR166f | 21 | 22,025.82 | 21,807.02 | 13,613.70 | TCGGACCAGGCTTCATCCCCC |

| miR167a | 22 | 13,753.66 | 10,694.43 | 9504.66 | TGAAGCTGCCAGCATGATCTAA |

| miR167c | 21 | 13,810.71 | 10,694.43 | 9617.24 | TGAAGCTGCCAGCATGATCTA |

| miR167d | 20 | 5357.89 | 3905.87 | 4615.63 | TGAAGCTGCCAGCATGATCT |

| miR168a | 21 | 13,929.56 | 14,404.56 | 14,787.71 | TCGCTTGGTGCAGGTCGGGAA |

| miR169a | 21 | 19.02 | 17.79 | 40.21 | CAGCCAAGGATGACTTGCCGA |

| miR169g | 22 | 9.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | TAGCCAAGGATGACTTGCCTGC |

| miR169m | 21 | 19.02 | 8.90 | 24.12 | TGAGCCAAAGATGACTTGCCG |

| miR169n | 21 | 23.77 | 44.49 | 104.54 | CAGCCAAGGATGACTTGCCGG |

| miR171a | 21 | 456.40 | 631.70 | 321.65 | TTGAGCCGTGCCAATATCACG |

| miR171f | 21 | 1150.50 | 845.23 | 1085.56 | TGATTGAGCCGCGCCAATATC |

| miR171g | 22 | 1150.50 | 845.23 | 1085.56 | TGATTGAGCCGCGCCAATATCT |

| miR172a | 21 | 123.61 | 124.56 | 88.45 | AGAATCTTGATGATGCTGCAT |

| miR172b | 21 | 199.67 | 373.68 | 225.15 | GGAATCTTGATGATGCTGCAT |

| miR172d | 21 | 23.77 | 26.69 | 16.08 | AGAATCTTGATGATGCTGCAG |

| miR2111a-3p | 21 | 38.03 | 44.49 | 16.08 | GTCCTCGGGATGCGGATTACC |

| miR2111a-5p | 21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.08 | TAATCTGCATCCTGAGGTTTA |

| miR2111b-3p | 21 | 85.57 | 35.59 | 64.33 | ATCCTCGGGATACAGATTACC |

| miR2111c | 21 | 4.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | TAATCTGCATCCTGGGGTTTA |

| miR390a | 21 | 2700.34 | 1788.34 | 1648.44 | AAGCTCAGGAGGGATAGCGCC |

| miR393 | 21 | 52.30 | 44.49 | 80.41 | TCCAAAGGGATCGCATTGATC |

| miR394a | 20 | 3342.14 | 3016.15 | 3337.09 | TTGGCATTCTGTCCACCTCC |

| miR395a | 21 | 16,382.69 | 21,735.84 | 27,243.49 | CTGAAGTGTTTGGGGGAACTC |

| miR395d | 21 | 6608.22 | 6317.01 | 5588.61 | CTGAAGTGTTTGGGGGGACTC |

| miR397a | 22 | 4.75 | 17.79 | 8.04 | TCATTGAGTGCAGCGTTGATGT |

| miR399a | 21 | 0.00 | 8.90 | 0.00 | TGCCAAAGGAGATTTGCCCGG |

| miR403 | 21 | 26,927.32 | 24,342.72 | 26,310.71 | TTAGATTCACGCACAAACTCG |

| miR6029 | 21 | 256.72 | 302.50 | 217.11 | TGGGGTTGTGATTTCAGGCTT |

| miR6030 | 22 | 1093.45 | 818.54 | 522.68 | TCCACCCATACCATACAGACCC |

| miR6031 | 24 | 1179.02 | 1574.80 | 868.45 | AAGAGGTTCGGAGCGGTTTGAAGC |

| miR6034 | 21 | 19.02 | 26.69 | 88.45 | TCTGATGTATATAGCTTTGGG |

| miR6035 | 21 | 61.80 | 160.15 | 88.45 | TGGAGTAGAAAATGCAGTCGT |

| miR824 | 21 | 1911.16 | 1823.92 | 1286.59 | TAGACCATTTGTGAGAAGGGA |

| miR860 | 21 | 4.75 | 8.90 | 32.16 | TCAATACATTGGACTACATAT |

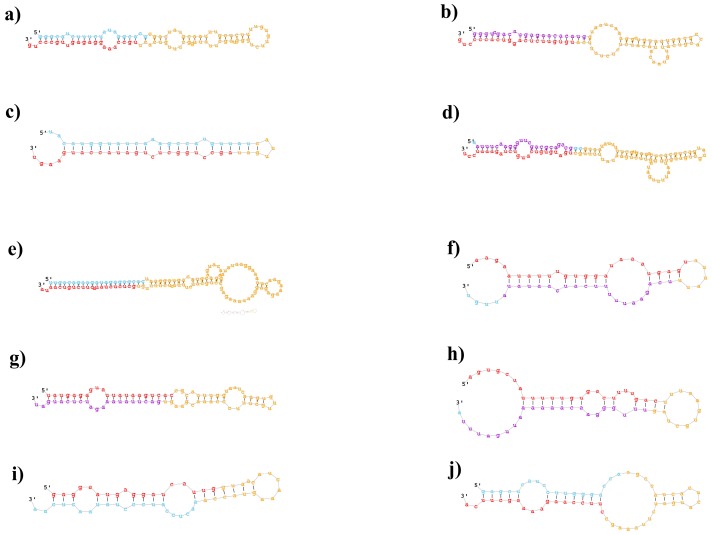

To identify novel miRNAs in B. napus, RNAfold and Mireap were utilized. A characteristic stem-loop precursor is the most important characterization for new miRNAs (Meyers et al., 2008). In the current study, a total of 103 small RNAs were regarded as candidate novel miRNAs in B. napus (Table 3). These novel miRNAs showed a length distribution between 18 nt and 25 nt (but no miRNAs were 19 nt in length) with 44 miRNAs of 21 nt long and 32 miRNAs of 24 nt long. (Table 3). Similar to past analyses with B. napus and other plant species, the minimum free energy (AMFE) varied from −171.9 to −26.9 kcal moL−1 (Table 3). The precursor length of these miRNAs was 250 nt, and some selected secondary structures are shown in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Predicted novel miRNA families and their transcript abundance identified in the three samples.

| miRNA | Length | CK | T1 | T3 | Hairpin Energy (kcal moL−1) | Mature Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novel-001 | 21 | 128.4 | 160.1 | 72.4 | −80.5 | auaacuugguuuugcuccuac |

| Novel-002 | 21 | 12,845.6 | 12,011.2 | 14,924.4 | −67.3 | cggcucugauaccaauugaug |

| Novel-003 | 23 | 1625.9 | 2117.5 | 3264.7 | −78.5 | ugcucacggcucuuucugucagu |

| Novel-004 | 21 | 228.2 | 213.5 | 193.0 | −73.8 | ugccaaaggagaguugcccug |

| Novel-005 | 20 | 85.6 | 231.3 | 386.0 | −61.2 | uguguucucaggucaccccu |

| Novel-006 | 21 | 366.1 | 284.7 | 587.0 | −51.2 | uuggagcaucgagugaagagc |

| Novel-007 | 21 | 4278.7 | 3772.4 | 3393.4 | −67.3 | ucgauaaaccucugcauccag |

| Novel-008 | 24 | 2386.6 | 952.0 | 554.8 | −72.9 | gaugacgguaucucuccuacguag |

| Novel-009 | 22 | 23.8 | 17.8 | 217.1 | −119.2 | cagaagauguaugcuaaauugg |

| Novel-010 | 18 | 0.0 | 17.8 | 128.7 | −49.4 | gaggaaugaggaucauug |

| Novel-011 | 24 | 19,216.1 | 30,481.8 | 22,209.7 | −69.5 | agagauuuuuguuacuguuaacug |

| Novel-012 | 25 | 118.9 | 275.8 | 635.3 | −57.7 | gucaauugauggguaguaguucauu |

| Novel-013 | 24 | 2752.6 | 2811.5 | 1889.7 | −60.5 | agccuggcucugauaccaugaagu |

| Novel-014 | 21 | 294.8 | 266.9 | 241.2 | −68.3 | gacuuauaauaaucucaugaa |

| Novel-015 | 18 | 57.0 | 0.0 | 48.2 | −69.1 | cuuccaagaaaagcuuca |

| Novel-016 | 20 | 789.2 | 765.2 | 675.5 | −75.9 | ugaaugucuuucucuucauc |

| Novel-017 | 21 | 1141.0 | 1512.5 | 297.5 | −76.1 | uuguggaaccgugugaauacc |

| Novel-018 | 24 | 57.0 | 53.4 | 72.4 | −55.4 | ugaugugucaugucuagaaauccu |

| Novel-019 | 21 | 95.1 | 53.4 | 64.3 | −95.6 | uccccaguuuggauuguuugc |

| Novel-020 | 21 | 9555.8 | 7028.8 | 8202.0 | −88 | uaugugugcucacucucuauc |

| Novel-021 | 24 | 42.8 | 80.1 | 72.4 | −56.1 | acaggugguggaacaaauaugagu |

| Novel-022 | 21 | 713.1 | 409.3 | 289.5 | −72.1 | cgauauugguacgguugaauc |

| Novel-023 | 21 | 746.4 | 596.1 | 1101.6 | −76.4 | gauccucugaacacuucauug |

| Novel-024 | 24 | 142.6 | 329.2 | 176.9 | −135.7 | auuuuuagaacuucaauggguaga |

| Novel-025 | 21 | 171.1 | 160.1 | 257.3 | −62.4 | aucaugcgaucucuucggauu |

| Novel-026 | 21 | 26,375.8 | 21,495.6 | 24,670.3 | −82.4 | gcucucuagucuucugucauc |

| Novel-027 | 21 | 351.8 | 249.1 | 482.5 | −75.1 | guucccugaaacgcuucauug |

| Novel-028 | 20 | 8804.6 | 9164.1 | 9794.1 | −80.6 | uuggacugaagggagcuccu |

| Novel-029 | 21 | 309.0 | 302.5 | 442.3 | −83.2 | uuuugcguuucaacucggucc |

| Novel-030 | 21 | 13,311.5 | 10854.6 | 12,029.6 | −70.1 | cuugcauaucuuaggagcuuu |

| Novel-031 | 21 | 5191.5 | 2953.9 | 2830.5 | −67.3 | guucaauaaagcugugggaag |

| Novel-032 | 21 | 931.8 | 889.7 | 772.0 | −80.4 | uuggacugaagggaacucccu |

| Novel-033 | 24 | 156.9 | 222.4 | 241.2 | −53.5 | agcuaugguuuauguggacucagu |

| Novel-034 | 22 | 27,345.7 | 25,695.1 | 24,799.0 | −72.4 | gcucacugcucuuucugucaga |

| Novel-035 | 23 | 1606.9 | 1085.5 | 852.4 | −74.3 | gcucauucucguucugucauaac |

| Novel-036 | 21 | 1882.6 | 8719.2 | 10,807.3 | −69.9 | uguguucucaggucaccccug |

| Novel-037 | 21 | 1331.2 | 1245.6 | 1769.1 | −88.6 | gcuuacucucucucugucacc |

| Novel-038 | 23 | 156.9 | 302.5 | 233.2 | −58.6 | uucggaccaggcuucauucccca |

| Novel-039 | 23 | 608.5 | 1254.5 | 876.5 | −80 | guagguagacgcacuguuucuca |

| Novel-040 | 24 | 47.5 | 71.2 | 48.2 | −85.1 | ugaguuaucauuggucuuguguca |

| Novel-041 | 21 | 936.6 | 498.2 | 619.2 | −71.8 | gacuuauaaugaucucaugaa |

| Novel-042 | 21 | 185.4 | 329.2 | 209.1 | −100.9 | uugguuuaacuuggauuuuga |

| Novel-043 | 22 | 855.7 | 373.7 | 410.1 | −70.6 | cguacagaguagucaagcauga |

| Novel-044 | 21 | 256.7 | 462.7 | 257.3 | −65.1 | uguuuuguggguuucuaccga |

| Novel-045 | 21 | 2838.2 | 1868.4 | 3015.4 | −95.5 | cccgccuugcaucaacugaau |

| Novel-046 | 21 | 23,542.4 | 23,648.7 | 19,234.5 | −83.2 | uuggacugaagggagcucccu |

| Novel-047 | 24 | 584.8 | 898.6 | 619.2 | −98.7 | auauuccgauaagaacuucacucu |

| Novel-048 | 22 | 261.5 | 240.2 | 345.8 | −79.4 | uuucaucuuagagaauguuguc |

| Novel-049 | 22 | 551.5 | 284.7 | 241.2 | −63.6 | gcucucuauacuucugucaaua |

| Novel-050 | 23 | 2828.7 | 2615.8 | 2098.7 | −53.2 | uuggucacgugacuugugcuuua |

| Novel-051 | 24 | 5434.0 | 9635.7 | 6577.7 | −57.3 | aaacagcgguauucugacggacau |

| Novel-052 | 24 | 180.7 | 204.6 | 128.7 | −49.4 | aacuucggcuaagagauaguucuu |

| Novel-053 | 24 | 142.6 | 391.5 | 80.4 | −49.7 | aaauagaucuuuuugaaacaaauu |

| Novel-054 | 24 | 271.0 | 258.0 | 329.7 | −60.1 | auacagacucauauggaccaugug |

| Novel-055 | 21 | 375.6 | 293.6 | 514.6 | −83.8 | gcuuacucucucucugucacc |

| Novel-056 | 24 | 118.9 | 124.6 | 48.2 | −51.2 | aaagagcgacuauaguauaacuau |

| Novel-057 | 23 | 565.7 | 783.0 | 562.9 | −67.3 | agacuguaucuuauauuaugcua |

| Novel-058 | 21 | 266.2 | 160.1 | 144.7 | −67.5 | uugacagaagagagcgagcac |

| Novel-059 | 23 | 988.9 | 1067.7 | 1479.6 | −88 | ugcucaccucucuuucugucagu |

| Novel-060 | 21 | 1835.1 | 1708.3 | 1688.6 | −85.5 | uuuggauugaagggagcuccu |

| Novel-061 | 24 | 2572.0 | 4279.5 | 3473.8 | −101.8 | aggauuucauuuuccgucggaaug |

| Novel-062 | 24 | 14.3 | 177.9 | 64.3 | −32.2 | aaacgacguuguuuuauagcucuc |

| Novel-063 | 24 | 1373.9 | 2224.3 | 1897.7 | −84.5 | aggauuucauuuuccgucggaaug |

| Novel-064 | 24 | 3123.5 | 5035.8 | 4318.1 | −114 | aggauuucauuuuccgucggaaug |

| Novel-065 | 24 | 137.9 | 71.2 | 112.6 | −26.9 | aucuuaauugauugacaacucagc |

| Novel-066 | 24 | 589.5 | 702.9 | 418.1 | −61.1 | gauuaacccggaguucuuagaaug |

| Novel-067 | 24 | 285.2 | 427.1 | 217.1 | −65.8 | aggaugugguucuuagcggaaguu |

| Novel-068 | 24 | 347.1 | 240.2 | 249.3 | −36.9 | auaugaucugcacuuuugaacugu |

| Novel-069 | 20 | 7644.6 | 8399.0 | 8346.7 | −77 | ucccaaauguagacaaagca |

| Novel-070 | 24 | 3670.2 | 4341.8 | 3304.9 | −59 | agaauccgucucuuaacuuuuaac |

| Novel-071 | 21 | 698.9 | 1307.9 | 916.7 | −76.8 | uaagcugccagcaugaucuug |

| Novel-072 | 24 | 156.9 | 195.7 | 112.6 | −87.5 | aacgauuuuuguuacugauaacug |

| Novel-073 | 21 | 114.1 | 213.5 | 112.6 | −63.2 | uaugagaguauuauaagucac |

| Novel-074 | 21 | 389.8 | 231.3 | 225.2 | −171.9 | uaagacgagaaauugacaucc |

| Novel-075 | 24 | 247.2 | 480.4 | 659.4 | −60.1 | gucaacugauggugagagagaggu |

| Novel-076 | 21 | 332.8 | 756.3 | 1117.7 | −86.8 | uuguagaauuuugggaagggc |

| Novel-077 | 21 | 332.8 | 756.3 | 1166.0 | −84.3 | uuguagaauuuugggaagggc |

| Novel-078 | 21 | 318.5 | 444.9 | 450.3 | −104.3 | auuuucgauugguggauugug |

| Novel-079 | 22 | 556.2 | 320.3 | 249.3 | −73.6 | uuuugccuacuccucccauacc |

| Novel-080 | 20 | 8747.6 | 9173.0 | 9770.0 | −80.7 | uuggacugaagggagcuccu |

| Novel-081 | 21 | 38.0 | 80.1 | 160.8 | −55.2 | uggaugaugcuuggcucgaga |

| Novel-082 | 22 | 294.8 | 533.8 | 667.4 | −78.9 | ugguauugguaguaaugagugu |

| Novel-083 | 21 | 23,875.2 | 23,897.9 | 19,491.8 | −87 | uuggacugaagggagcucccu |

| Novel-084 | 22 | 76.1 | 106.8 | 209.1 | −70.1 | ucuugcuuaaauggguauucca |

| Novel-085 | 24 | 5196.2 | 15,258.7 | 5315.2 | −32.2 | agugcuauuuuugugacuuuugac |

| Novel-086 | 21 | 99,598.8 | 102,388.9 | 109,022.2 | −79.3 | uuuccaaauguagacaaagca |

| Novel-087 | 21 | 4350.0 | 4964.6 | 5693.1 | −59.8 | uuagaugaccaucaacaaaua |

| Novel-088 | 21 | 418.4 | 409.3 | 530.7 | −65.5 | ggacuguugucuggcucgagg |

| Novel-089 | 24 | 404.1 | 409.3 | 394.0 | −79.6 | caccgagguucguacggaggacgu |

| Novel-090 | 23 | 76.1 | 169.0 | 88.5 | −68.6 | gauacaugguuuguuagcugaua |

| Novel-091 | 20 | 42.8 | 106.8 | 201.0 | −53.3 | uguguucucaggucaccccu |

| Novel-092 | 21 | 8785.6 | 7687.2 | 6915.4 | −64.9 | ucgauaaaccucugcauccag |

| Novel-093 | 21 | 394.6 | 355.9 | 587.0 | −63.1 | uuugauuaggagcucauuguu |

| Novel-094 | 21 | 161.6 | 160.1 | 128.7 | −67.8 | ggacuguugucuggcucgagg |

| Novel-095 | 24 | 432.6 | 409.3 | 289.5 | −54.7 | aaaccgauucuauuagagcaugau |

| Novel-096 | 21 | 36,853.9 | 36,327.2 | 29,527.2 | −97.3 | uuggacugaagggagcucccu |

| Novel-097 | 22 | 451.6 | 524.9 | 377.9 | −75.12 | cuuaucucgaacgacuuucucg |

| Novel-098 | 24 | 52.3 | 275.8 | 297.5 | −88.1 | guuauuggaguuaauagagaaccg |

| Novel-099 | 21 | 841.5 | 6753.0 | 8177.9 | −65.4 | acagggaacaagcagagcaug |

| Novel-100 | 21 | 1359.7 | 783.0 | 675.5 | −66 | uucgcaggagagauagcgcca |

| Novel-101 | 24 | 1963.5 | 2188.7 | 2267.6 | −123.2 | ucuuaacuucggauaagagacggu |

| Novel-102 | 24 | 1621.2 | 1743.8 | 1616.3 | −74.7 | uauuauagagugaaccauuggagu |

| Novel-103 | 24 | 242.5 | 436.0 | 418.1 | −36.3 | aaugauaaggcgacuguaccagcu |

Figure 3.

Predicted secondary structures of selected eight novel miRNAs in our study. The red indicates mature miRNA sequences, yellow indicates ring structure and purple indicates star sequences. (a) Novel-004; (b) Novel-036; (c) Novel-013; (d) Novel-018; (e) Novel-049; (f) Novel-059; (g) Novel-073; (h) Novel-092; (i) Novel-010; (j) Novel-015.

2.3. Target Prediction and Functional Analysis of miRNAs

Target prediction is crucial to understanding the functions of miRNAs. In this study, 460 putative target genes were predicted for 33 known and 44 novel miRNAs with an average of 5.97 targets per miRNA (psRNA Target, 2011 release; http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/) [43]. Of the 77 miRNAs, miR156d had the most putative targets (40) among the known miRNAs, and Novel-015 had the most potential targets (50) within the novel miRNAs (Tables S1 and S2).

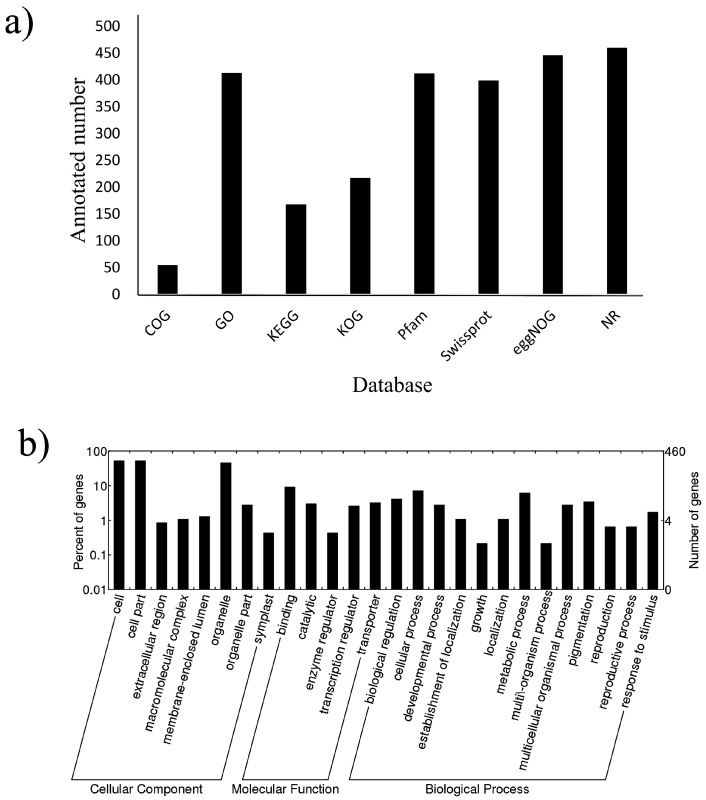

To further understand the crucial roles of miRNAs, all target genes were annotated in eight databases. Only 55 genes were annotated in the COG database, and almost all genes were annotated in the Swissprot (399), Pfam (412), GO (413), eggnog (446), and NR (460) databases (Figure 4a). In addition, all target genes were sent to GO functional classification (http://www.geneontology.org/) [44]. The results showed that these target genes were involved in 26 terms related to 8 cellular components (cell/cell part), 5 molecular functions (binding process) and 13 biological processes (metabolic process) (Figure 4b). Interestingly, eight target genes were involved in stimulus response processes (GO: 0050896).

Figure 4.

Diagrams of differentially expressed known (a) and novel (b) miRNAs between each treatment comparison.

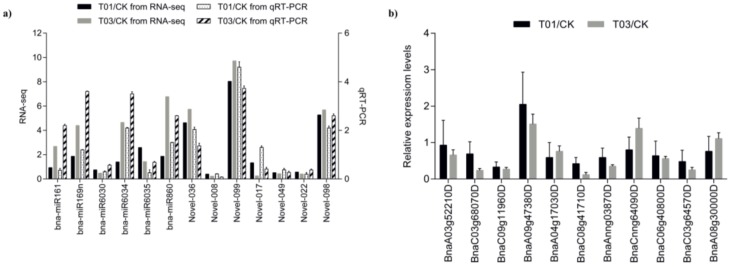

2.4. qRT-PCR Validation

To test the reliability of high-throughput sequencing results, the expression patterns of 13 miRNAs (including 6 known and 7 novel miRNAs) were observed using qRT-PCR. As expected, the qRT-PCR demonstrated a high consistency with sRNA sequencing data (Figure 5a). The correlation coefficient between NGS and qRT-PCR data were 0.7079 (P < 0.05) and 0.7694 (P < 0.05) using T1/CK and T3/CK, respectively, suggesting the NGS were reliable. The sensitivity of the fold changes between the two different methodologies were slightly different among three samples. Eleven target genes including four for miR6030, four for Novel-010, two for Novel-015 and one for Novel-090 were used to detect expression changes (Figure 5b). Reverse expression changes with miRNAs were detected indicating these predicted target genes were possibly regulated by corresponding miRNAs except these pairs: Novel-015 and BnaA03g52210D, miRNA Novel-10 and BnaA08g30000D, miR3060 and BnaC08g41710D and BnaAnng03870D. The possible reasons are: (1) these genes we selected may not real targets of corresponding miRNAs; (2) the low expression level of miRNAs or (3) these targets were not degrading immediately.

Figure 5.

Validation and comparison of the expression of 13 miRNAs between qRT–PCR and small RNA sequencing (a) and 11 corresponding target genes (b). Fold change of miRNA expression relative to the control sample.

2.5. miRNA Expression in Response to Cd Stress

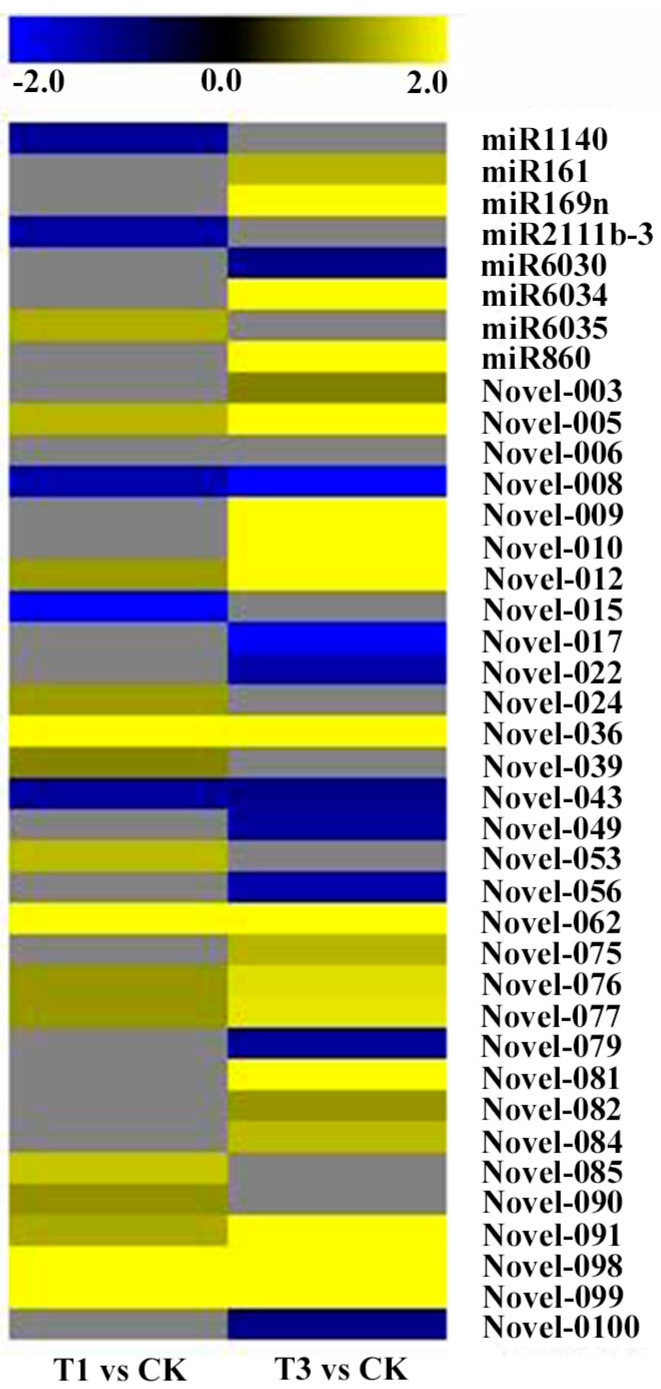

Among the 44 known miRNAs, 3 miRNAs were differentially expressed in T01 comparing CK library (miR1140 and miR2111b-3p were down-regulated while miR6035 was up-regulated). When comparing T03 to CK, 5 miRNAs were differentially expressed (miR161, miR169n, miR6034 and miR860 were up-regulated while miR6030 was down-regulated) (Figure 6). In addition, miR161, miR169n and miR6034 were differentially expressed in comparisons of T03 vs CK and T03 vs T01. Lastly, 3, 2 and 0 miRNAs were specific differentially expressed in comparison of T01 vs. CK, T03 vs. CK, and T03 vs. T01, respectively (Figure 7a).

Figure 6.

Differential expression of conserved miRNAs and novel miRNAs between two samples.

Figure 7.

Annotation of predicted target genes for miRNAs. (a) Number of target genes in various databases; (b) Histogram of gene ontology (GO) classification of predicted target genes. The left and right y-axis indicates the percentage and number of a specific category of genes in that main category, respectively.

From the novel 103 miRNAs, 31 were differentially expressed among the three libraries (Figure 6). When comparing T01 to CK, 17 were differentially expressed (3 down-regulated and 14 up-regulated). A comparison of T03 to CK demonstrated 24 that were differentially expressed (8 down-regulated and 16 up-regulated). Lastly, when comparing between T03 and T01, there were 11 differentially expressed (5 down-regulated and 6 up-regulated) (Figure 6). Furthermore, 3 miRNAs were specific differentially expressed between T01 and CK, 8 miRNAs between T03 and CK, and 1 miRNA between T03 vs T01. The two miRNAs Novel-062 and Novel-012 were common differentially expressed in all three comparisons (Figure 7b).

3. Discussion

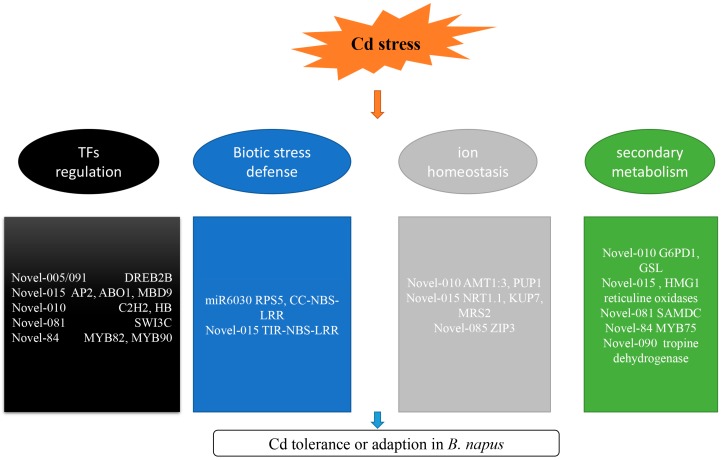

Cadmium is a widespread and toxic heavy metal pollutant that is detrimental to food and drinking water supplies [45]. B. napus, one of the most important oil and biofuel crops, is also under threat even though it is moderately tolerant of heavy metals [40]. To adapt to cadmium stress, fine and complex regulatory mechanisms have evolved in plants. In the last few years, miRNAs have been regarded as crucial regulators in a plant’s response to toxic metal stress [46]. Identification of miRNAs and corresponding target genes is necessary when exploring regulatory stress mechanisms. In the current study, miRNA profiles were generated of B. napus seedlings exposed to Cd stress. In total, 39 differentially expressed miRNAs were identified, of which 8 are known and 31 are novel. Cd responsive miRNAs may contribute to Cd tolerance by regulating transcription factors (TFs) that are important in biotic stress responses, ion transporters and secondary metabolism (Table S3, Figure 8).

Figure 8.

A hypothetical integrated schematic diagram of the mechanisms involved in Cd tolerance in Brassica napus.

3.1. miRNAs Involved in TF Regulation

TFs have central roles in plant growth and development, as well as biotic and abiotic stresses. Several TFs that are responsive to heavy metal stress have been identified previously [21]. APETALA2 (AP2)/ethylene-responsive-element-binding protein (EREBP) family and MYeloBlastosis Protein (MYB) proteins are involved in essential responses to heavy metal stress. Additionally, several members of AP2 TF can regulate pathogenesis-related and dehydration responsive genes by binding their promoters [47]. In a previous work, researchers have suggested that ERF1 and ERF2 genes were involved in a response to Cd treatment in Arabidopsis thaliana roots [23]. In addition, DREB2A was also induced by Cd. In the current study, five AP2 genes were predicted as target genes for novel-05, novel-15 and novel-91. BnaAnng23490D (DREB2B) was a common target for novel-05 and novel-91, which were both up-regulated after 1 and 3 days of Cd treatment. However, novel-15 was down-regulated after 1 day of Cd treatment. In A. thaliana, MYB4 was induced after Cd and Zn-treatments [20], while MYB43, MYB48 and MYB124 were strongly and specifically expressed after Cd treatment in roots [23]. Glucosinolate (GSL) has important functions in the response to nutritional status, and biotic and abiotic stresses [48]. Its synthesis is regulated by MYB28, which is highly induced by Zn deficiency and exposure to high concentrations of Cd [20]. Currently, three BnMYBs (two BnMYB82s and one BnMYB90) genes were targeted by novel-84, which was up-regulated after 3 days of Cd treatment. Moreover, some other TFs such as C2H2, HB and ABO1 (ABA-OVERLY SENSITIVE 1) were also detected as target genes for differentially expressed miRNAs.

3.2. miRNAs Involved in Biotic Stress Responses

Previous researches identified crosstalk between pathogen defense signaling and Cd regulation mechanisms [26]. RESISTANT TO P. SYRINGAE 5 (RPS5) is involved in resistance against the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae [49]. Five RPS5 genes and 11 disease resistance protein genes (CC-NBS-LRR class) were targeted by miR6030, which was down-regulated after 3 days of Cd treatment. In addition, three PR-protein genes (TIR-NBS-LRR class) were predicted as target genes for novel-15, which was down-regulated after 1 day of Cd treatment. Moreover, another two genes BnaA01g20350D and BnaA07g17000D, involved in biotic stress were also predicted as target genes for novel-10 and novel-15, respectively. These data suggest that stresses associated with heavy metals and biotic factors may share the same signal transduction pathway.

3.3. miRNAs Involved in Ion Transport

In general, crops take up metal ions and nutrients from soil using highly effective transmembrane protein transporters. In this system, metal transporters located in the plasma membrane or tonoplast, have crucial roles in ion homeostasis. If a toxic Cd ion was drawn into a cell, the ion could be transported out or sequestered to the vacuole. In Arabidopsis, the important metal transporter ZIP (ZRT, IRT-like protein) family, located in plasma membranes, was induced in both shoots and roots in response to Zn-limiting conditions. ZIP proteins have essential roles in divalent cation transport for many plant species [50]. Several members of the ZIP family function in Cd uptake and transport, and are involved in the xylem unloading process [51]. In the current study, BnaC04g42780D (ZIP3) was predicted as a target gene for novel-85, which was up-regulated by 1.5 fold after only 1 day of Cd treatment. Cadmium can also influence water uptake and nutrient metabolism [52]. In total, four magnesium transporter genes (MRS2), one potassium ion transmembrane transporter gene (KUP7) and one nitrate transmembrane transporter gene (NRT1.1) were predicted as target genes for novel-015, which was down-regulated after 1 day of Cd treatment. One purine nucleoside transmembrane transporter gene (PUP1) and one ammonium transmembrane transporter gene (AMT1:3) were targeted by novel-010, which was up-regulated after 3 days of Cd treatment. Other transporters such as NRAMP (natural resistance-associated macrophage protein) [53], HMA (P1B-ATPases) [51], ABC transporters [54] and CDF (cation diffusion facilitator) [51] are crucial for metal transport and ion homeostasis in Arabidopsis. However, no homologs of these genes were predicted as target genes for differentially expressed miRNAs in B. napus. Some reasons for this include differences in Cd concentration, duration of Cd treatment and sequencing depth.

3.4. miRNAs Involved in Secondary Metabolism

Secondary metabolites have important functions in response to biotic and abiotic stresses [55]. Genes involved in the biosynthesis of flavonoids and isoprenoids were predicted as target genes for miRNAs in this study. Flavonoids were used in transgenic engineering to enhance resistance to various stresses [56]. PRODUCTION OF ANTHOCYANIN PIGMENT 1 (PAP1) contains a MYB domain and is involved in anthocyanin metabolism and radical scavenging [57]. In myb12 mutants, PAP1 transcription did not occur in response to auxin and ethylene [58]. PAP1 regulates anthocyanin accumulation by interacting with JAZ proteins [59]. Currently, five homologous PAP1 genes in B. napus were predicted as target genes for novel-084, which was up-regulated after 3 days of Cd treatment. HYDROXY METHYLGLUTARYL COA REDUCTASE 1 (HMG1) encodes a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, and is involved in the first step in isoprenoid biosynthesis [60]. Its expression is activated in leaf tissue under dark conditions but not regulated by light in roots. Two copies of HMG1 in B. napus were predicted as target genes for novel-015, which was down-regulated after 1 day of Cd treatment. Other genes involved in secondary metabolite synthesis were also predicted as target genes for differentially expressed miRNAs.

Based on the microRNA profile analysis with or without Cd treatment, 4 known miRNAs and 12 novel miRNAs were identified as being responsive to Cd tolerance in B. napus. These miRNAs were mainly involved in TFs, biotic stress defense, ion homeostasis and secondary metabolism synthesis. The results provide more information about the mechanism of toxic metal resistance in B. napus and other important crops.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Culture and Treatment

Seeds of Brassica napus (Zhongshaung 11) were surface sterilized in 1.2% NaOCl and germinated at 22 ± 1 °C for 7 d on a plastic net floating on distilled water. Seedlings were then transferred to 1/4-strength modified Hoagland nutrient solution for another 7 d with a 14/10 h light/dark cycle at 22 ± 1 °C and 250 μmoL m−2 s−1 light intensity. Next, the seedlings were transferred to fresh nutrient solution containing either 0 μM or 1000 μM CdCl2 for 0 d, 1 d, or 3 d. Following this treatment, seedlings (including roots and shoots) were harvested, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

4.2. Construction and Sequencing of Small RNA Libraries

Small RNA libraries were created based on our previous work [34]. Total RNA was isolated from whole B. napus plants using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Three sets of total RNA were prepared from samples after 0 d (CK), 1 d (T01) and 3 d (T03) treatments. The quality of the RNA samples was checked with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and then all three RNA samples were sent to Beijing Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for sRNA library construction and Solexa sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. Furthermore, all sequencing data were uploaded on NCBI with accession number SRP118762.

4.3. Analysis of Small RNA Sequencing Data

Clean data were screened from raw data by removing contaminants, adaptors, and low-quality reads. Unique reads were then mapped on a B. napus reference genome (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/brassicanapus/) [61] using the SOAP2 program with default parameters [62]. Sequences with a best match were retained and those that were matched on non-coding RNAs, exclusive miRNAs in the Rfam 13.0 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Rfam), and NCBI GenBank 225.0 (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/GenBank/) databases were removed. The website miRBase 21.0 (http://www.mirbase.org/index.shtml) was used to identify known miRNAs with a maximum of two mismatches. The remaining unmapped sequences were used to predict novel miRNAs using Mireap_0.2 software (https://sourceforge.net/projects/mireap/) with basic criteria [63].

4.4. Differential Expression Analysis of miRNAs under Cd Stress

To screen Cd-responsive miRNAs, their expression (including known and novel miRNAs) in each sample was normalized using following formula:

| normalized expression = actual miRNA count/total count of clean reads × 1,000,000 |

The expression value was regarded as 0.01 for further analysis if the read count of a miRNA was 0. The fold change between the T01 or T03 and control (CK) sample was calculated as:

| fold change = log2 (T01 or T03/CK) |

The miRNAs with absolute value of fold changes ≥1 and with P ≤ 0.05 were considered to be Cd-responsive miRNAs. FDR (False positive rate) was calculated using the Benjamin correction value of the statistical P value and the software IDGE6 was used to select differentially expressed miRNAs.

4.5. Prediction of miRNA Targets

The website psRNATarget 2011 (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/) was used to predict target genes of miRNAs according to default parameters. Moreover, gene ontology (GO) was used for function annotation of the target genes in Blast2GO 5.0 software (http://www.blast2go.org/).

4.6. Validation of Mature miRNAs and Corresponding Target Genes

To confirm the sequencing data, 13 miRNAs and 13 corresponding target genes were randomly selected for quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). RNA used for qRT-PCR was the same as that used for library construction. For miRNA qRT-PCR, miRcute miRNA qPCR Detection Kit was used on a CFX96 Real-time System (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The forward primers of miRNAs were designed based on the mature miRNA sequence (Table S4) and the reverse primers were designed based on the adapter sequences, which were provided by the cDNA synthesis kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). For the qRT-PCR of target genes, specific primers (Table S5) were designed using the software Primer Premier 5.0 (PREMIER Biosoft Int., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The B. napus Actin7 and U6 snRNA of B. napus were used as the references for target genes and miRNAs, respectively. The relative expression level of each miRNA was calculated using the comparative method (2−ΔΔCt). Three biological replicates with three technical replicates for each miRNA were performed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771830), the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities (XDJK2017A009), the Chongqing Science and Technology Commission (cstc2016shmszx80083), Technology Nova Foster Project of Chongqing City (KJXX2017010), National Undergraduate Training Program for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (201610635037) and Chongqing basic research and frontier exploration project (cstc2015jcyjBX0001).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/5/1431/s1, Table S1. Predicted target genes of miRNAs in this study. Table S2. Function descriptions of target genes predicted in this study. Table S3. Predicted target genes of differentially expressed miRNAs in this study. Table S4. Mature sequences of miRNAs used for qRT-PCR to validate sRNA sequencing data. Table S5. the primers used for qRT-PCR of target genes.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: H.J., L.L. Performed the experiments: H.J., B.Y. Analyzed the data: A.Z., J.M., Y.D., Z.C., H.J. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: X.X., J.L. Wrote the paper: H.J.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Xu Y.C., Chu L.L., Jin Q.J., Wang Y.J., Chen X., Zhao H., Xue Z.Y. Transcriptome-Wide Identification of miRNAs and Their Targets from Typha angustifolia by RNA-Seq and Their Response to Cadmium Stress. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0125462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han F.X.X., Banin A., Su Y., Monts D.L., Plodinec M.J., Kingery W.L., Triplett G.E. Industrial age anthropogenic inputs of heavy metals into the pedosphere. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:497–504. doi: 10.1007/s00114-002-0373-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nawrot T., Plusquin M., Hogervorst J., Roels H.A., Celis H., Thijs L., Vangronsveld J., Van Hecke E., Staessen J.A. Environmental exposure to cadmium and risk of cancer: A prospective population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamsi I.H., Wei K., Zhang G.P., Jilani G.H., Hassan M.J. Interactive effects of cadmium and aluminum on growth and antioxidative enzymes in soybean. Biol. Plant. 2008;52:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s10535-008-0036-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patra M., Bhowmik N., Bandopadhyay B., Sharma A. Comparison of mercury, lead and arsenic with respect to genotoxic effects on plant systems and the development of genetic tolerance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004;52:199–223. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2004.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DalCorso G., Farinati S., Furini A. Regulatory networks of cadmium stress in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010;5:663–667. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.6.11425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montero-Palmero M.B., Martin-Barranco A., Escobar C., Hernandez L.E. Early transcriptional responses to mercury: A role for ethylene in mercury-induced stress. New Phytol. 2014;201:116–130. doi: 10.1111/nph.12486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinka M., Vaculik M., Lux A. Plant Cell Responses to Cadmium and Zinc. Plant Cell Monogr. 2014;22:209–246. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patra M., Sharma A. Mercury toxicity in plants. Bot. Rev. 2000;66:379–422. doi: 10.1007/BF02868923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan M.J., Shao G.S., Zhang G.P. Influence of cadmium toxicity on growth and antioxidant enzyme activity in rice cultivars with different grain cadmium accumulation. J. Plant Nutr. 2005;28:1259–1270. doi: 10.1081/PLN-200063298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overmyer K., Brosche M., Kangasjarvi J. Reactive oxygen species and hormonal control of cell death. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:335–342. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edreva A. Generation and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts: A submolecular approach. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005;106:119–133. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2004.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim D.Y., Bovet L., Maeshima M., Martinoia E., Lee Y. The ABC transporter AtPDR8 is a cadmium extrusion pump conferring heavy metal resistance. Plant J. 2007;50:207–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueno D., Milner M.J., Yamaji N., Yokosho K., Koyama E., Zambrano M.C., Kaskie M., Ebbs S., Kochian L.V., Ma J.F. Elevated expression of TcHMA3 plays a key role in the extreme Cd tolerance in a Cd-hyperaccumulating ecotype of Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant J. 2011;66:852–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shukla D., Huda K.M.K., Banu M.S.A., Gill S.S., Tuteja R., Tuteja N. OsACA6, a P-type 2B Ca2+ ATPase functions in cadmium stress tolerance in tobacco by reducing the oxidative stress load. Planta. 2014;240:809–824. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonak C., Nakagami H., Hirt H. Heavy metal stress. Activation of distinct mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways by copper and cadmium. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3276–3283. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.045724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maksymiec W. Signaling responses in plants to heavy metal stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2007;29:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s11738-007-0036-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DalCorso G., Farinati S., Maistri S., Furini A. How plants cope with cadmium: Staking all on metabolism and gene expression. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008;50:1268–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero-Puertas M.C., Corpas F.J., Rodriguez-Serrano M., Gomez M., del Rio L.A., Sandalio L.M. Differential expression and regulation of antioxidative enzymes by cadmium in pea plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2007;164:1346–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Mortel J.E.V., Schat H., Moerland P.D., Van Themaat E.V.L., Van der Ent S., Blankestijn H., Ghandilyan A., Tsiatsiani S., Aarts M.G.M. Expression differences for genes involved in lignin, glutathione and sulphate metabolism in response to cadmium in Arabidopsis thaliana and the related Zn/Cd-hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31:301–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fusco N., Micheletto L., Dal Corso G., Borgato L., Furini A. Identification of cadmium-regulated genes by cDNA-AFLP in the heavy metal accumulator Brassica juncea L. J. Exp. Bot. 2005;56:3017–3027. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng H.B., Hua S.J., Shamsi I.H., Jilani G., Li Y.L., Jiang L.X. Cadmium-induced stress on the seed germination and seedling growth of Brassica napus L.; and its alleviation through exogenous plant growth regulators. Plant Growth Regul. 2009;58:47–59. doi: 10.1007/s10725-008-9351-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weber M., Trampczynska A., Clemens S. Comparative transcriptome analysis of toxic metal responses in Arabidopsis thaliana and the Cd2+-hypertolerant facultative metallophyte Arabidopsis halleri. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:950–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamas L., Dudikova J., Durcekova K., Halugkova L., Huttova J., Mistrik I., Olle M. Alterations of the gene expression, lipid peroxidation, proline and thiol content along the barley root exposed to cadmium. J. Plant Physiol. 2008;165:1193–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei W., Zhang Y.X., Han L., Guan Z.Q., Chai T.Y. A novel WRKY transcriptional factor from Thlaspi caerulescens negatively regulates the osmotic stress tolerance of transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:795–803. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0499-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki N., Koizumi N., Sano H. Screening of cadmium-responsive genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2001;24:1177–1188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00773.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding Y., Chen Z., Zhu C. Microarray-based analysis of cadmium-responsive microRNAs in rice (Oryza sativa) J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:3563–3573. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang M.F., Mao D.H., Xu L.W., Li D.Y., Song S.H., Chen C.Y. Integrated analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression profiles in response to Cd exposure in rice seedlings. BMC Genom. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu L., Wang Y., Zhai L.L., Xu Y.Y., Wang L.J., Zhu X.W., Gong Y.Q., Yu R.G., Limera C., Liu L.W. Genome-wide identification and characterization of cadmium-responsive microRNAs and their target genes in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) roots. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:4271–4287. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali E., Maodzeka A., Hussain N., Shamsi I.H., Jiang L.X. The alleviation of cadmium toxicity in oilseed rape (Brassica napus) by the application of salicylic acid. Plant Growth Regul. 2015;75:641–655. doi: 10.1007/s10725-014-9966-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali B., Qian P., Jin R., Ali S., Khan M., Aziz R., Tian T., Zhou W. Physiological and ultra-structural changes in Brassica napus seedlings induced by cadmium stress. Biol. Plant. 2014;58:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s10535-013-0358-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali B., Wang B., Ali S., Ghani M.A., Hayat M.T., Yang C., Xu L., Zhou W.J. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Ameliorates the Growth, Photosynthetic Gas Exchange Capacity, and Ultrastructural Changes Under Cadmium Stress in Brassica napus L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013;32:604–614. doi: 10.1007/s00344-013-9328-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali B., Song W.J., Hu W.Z., Luo X.N., Gill R.A., Wang J., Zhou W.J. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates lead-induced photosynthetic and ultrastructural changes in oilseed rape. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014;102:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jian H.J., Wang J., Wang T.Y., Wei L.J., Li J., Liu L.Z. Identification of Rapeseed MicroRNAs Involved in Early Stage Seed Germination under Salt and Drought Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J., Jian H.J., Wang T.Y., Wei L.J., Li J.N., Li C., Liu L.Z. Identification of microRNAs Actively Involved in Fatty Acid Biosynthesis in Developing Brassica napus Seeds Using High-Throughput Sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng H., Hao M., Wang W., Mei D., Wells R., Liu J., Wang H., Sang S., Tang M., Zhou R., et al. Integrative RNA- and miRNA-Profile Analysis Reveals a Likely Role of BR and Auxin Signaling in Branch Angle Regulation of B. napus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18050887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao J.Y., Xu Y.P., Zhao L., Li S.S., Cai X.Z. Tight regulation of the interaction between Brassica napus and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum at the microRNA level. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016;92:39–55. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0494-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie F.L., Huang S.Q., Guo K., Xiang A.L., Zhu Y.Y., Nie L., Yang Z.M. Computational identification of novel microRNAs and targets in Brassica napus. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1464–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang S.Q., Xiang A.L., Che L.L., Chen S., Li H., Song J.B., Yang Z.M. A set of miRNAs from Brassica napus in response to sulphate deficiency and cadmium stress. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2010;8:887–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Z.S., Song J.B., Yang Z.M. Genome-wide identification of Brassica napus microRNAs and their targets in response to cadmium. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:4597–4613. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozomara A. and Griffiths-Jones, S. Mirbase: Integrating miRNAs annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2011;39:152–157. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffiths-Jones S., Saini H.K., Van Dongen S., Enright A.J. Mirbase: Tools for miRNA genomics. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2008;36:154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai X., Zhao P.X. Psrnatarget: A plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2011;39:155–159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carbon S., Ireland A., Mungall C.J., Shu S., Marshall B., Lewis S.G.O. Hub ami, and group web presence working. amigo: Online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:288–289. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao J., Sun L., Yang X.E., Liu J.X. Transcriptomic Analysis of Cadmium Stress Response in the Heavy Metal Hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding Y.F., Zhu C. The role of microRNAs in copper and cadmium homeostasis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;386:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh K.B., Foley R.C., Onate-Sanchez L. Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:430–436. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirai M.Y., Sugiyama K., Sawada Y., Tohge T., Obayashi T., Suzuki A., Araki R., Sakurai N., Suzuki H., Aoki K., et al. Omics-based identification of Arabidopsis Myb transcription factors regulating aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6478–6483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611629104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karasov T.L., Kniskern J.M., Gao L.P., DeYoung B.J., Ding J., Dubiella U., Lastra R.O., Nallu S., Roux F., Innes R.W., et al. The long-term maintenance of a resistance polymorphism through diffuse interactions. Nature. 2014;512:436–440. doi: 10.1038/nature13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopez-Millan A.F., Ellis D.R., Grusak M.A. Identification and characterization of several new members of the ZIP family of metal ion transporters in Medicago truncatula. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004;54:583–596. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000038271.96019.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kramer U., Talke I.N., Hanikenne M. Transition metal transport. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2263–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deckert J. Cadmium toxicity in plants: Is there any analogy to its carcinogenic effect in mammalian cells? Biometals. 2005;18:475–481. doi: 10.1007/s10534-005-1245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nevo Y., Nelson N. The NRAMP family of metal-ion transporters. BBA Mol. Cell Res. 2006;1763:609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim D.Y., Bovet L., Kushnir S., Noh E.W., Martinoia E., Lee Y. AtATM3 is involved in heavy metal resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:922–932. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.074146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pusztahelyi T., Holb I.J., Pocsi I. Secondary metabolites in fungus-plant interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lorenc-Kukula K., Zuk M., Kulma A., Czemplik M., Kostyn K., Skala J., Starzycki M., Szopa J. Engineering Flax with the GT Family 1 Solanum sogarandinum Glycosyltransferase SsGT1 Confers Increased Resistance to Fusarium Infection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:6698–6705. doi: 10.1021/jf900833k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin D.H., Cho M., Choi M.G., Das P.K., Lee S.K., Choi S.B., Park Y.I. Identification of genes that may regulate the expression of the transcription factor production of anthocyanin pigment 1 (PAP1)/MYB75 involved in Arabidopsis anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:805–815. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Z., Shi M.Z., Xie D.Y. Regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana red pap1-D cells metabolically programmed by auxins. Planta. 2014;239:765–781. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-2011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qi T.C., Song S.S., Ren Q.C., Wu D.W., Huang H., Chen Y., Fan M., Peng W., Ren C.M., Xie D.X. The Jasmonate-ZIM-Domain Proteins Interact with the WD-Repeat/bHLH/MYB Complexes to Regulate Jasmonate-Mediated Anthocyanin Accumulation and Trichome Initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1795–1814. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leivar P., Antolin-Llovera M., Ferrero S., Closa M., Arro M., Ferrer A., Boronat A., Campos N. Multilevel control of Arabidopsis 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase by protein phosphatase 2A. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1494–1511. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chalhoub B., Denoeud F., Liu S., Parkin I.A., Tang H., Wang X., Chiquet J., Belcram H., Tong C., Samans B., et al. Plant genetics. early allopolyploid evolution in the post-neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science. 2014;345:950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1253435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li R.Q., Yu C., Li Y.R., Lam T.W., Yiu S.M., Kristiansen K., Wang J. SOAP2: An improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meyers B.C., Axtell M.J., Bartel B., Bartel D.P., Baulcombe D., Bowman J.L., Cao X., Carrington J.C., Chen X.M., Green P.J., et al. Criteria for Annotation of Plant MicroRNAs. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3186–3190. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.