Abstract

In order to better understand the etiology of obese type 2 diabetes (T2D) at the molecular level, the present study investigated the gene expression and DNA methylation profiles associated with T2D via systemic analysis. Gene expression (GSE64998) and DNA methylation profiles (GSE65057) from liver tissues of healthy controls and obese patients with T2D were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) and differentially-methylated genes (DMGs) were identified using the Limma package, and their overlapping genes were additionally determined. Enrichment analysis was performed using the BioCloud platform on the DEGs and the overlapping genes. Using Cytoscape software, protein-protein interaction (PPI), transcription factor target networks and microRNA (miRNA) target networks were then constructed in order to determine associated hub genes. In addition, a further GSE15653 dataset was utilized in order to validate the DEGs identified in the GSE64998 dataset analyses. A total of 251 DEGs, including 124 upregulated and 127 downregulated genes, were detected, and a total of 9,698 genes were demonstrated to be differentially methylated in obese patients with T2D compared with non-obese healthy controls. A total of 103 overlapping genes between the two datasets were revealed, including 47 upregulated genes and 56 downregulated genes. The identified overlapping genes were revealed to be strongly associated with fatty acid and glucose metabolic pathways, in addition to oxidation/reduction. The overlapping genes cyclin D1 (CCND1), PPARG coactivator α (PPARGC1A), fatty acid synthase (FASN), glucokinase (GCK), steraroyl-coA desaturase (SCD) and tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT) had higher degrees in the PPI, transcription target networks and miRNA target networks. In addition, among the 251 DEGs, a total of 35 DEGs were validated to be being shared genes between the datasets, which included a number of key genes in the PPI network, including CCND1, FASN and TAT. Abnormal gene expression and DNA methylation patterns that were implicated in fatty acid and glucose metabolic pathways and oxidation/reduction reactions were detected in obese patients with T2D. Furthermore, the CCND1, PPARGC1A, FANS, GCK, SCD and TAT genes may serve a role in the development of obesity-associated T2D.

Keywords: DNA methylation profile, gene expression profile, obesity-associated type 2 diabetes, protein-protein interaction network, regulatory network

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D), characterized by an inadequate β-cell response to progressive insulin resistance, is a highly prevalent disease affecting ~9% of the global population, and is fast-becoming a worldwide epidemic (1,2). The clinical symptoms of T2D include hyperglycemia, obesity, hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Furthermore, T2D may induce disease-specific complications, including blindness, renal failure and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, which may result in a reduced quality of life and an increased mortality rate of patients with T2D (3,4).

T2D is a complex disease that may be attributed to the interplay between environmental and genetic risk factors (5). Poor diets and sedentary lifestyles are prominent environmental contributors leading to the development of T2D (6). Epigenetic factors have been revealed to be heavily implicated in the complex interplay between environmental signals and intrinsic genetic alterations (7). DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification most commonly associated with cysteine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sites situated within the promoter region, and degrees of organismal DNA methylation are changeable depending on environmental factors. Furthermore, DNA methylation may modulate gene expression without altering the sequence of DNA via suppression of DNA transcription or modification of the surrounding chromatin. Methylation may suppress transcription by modulating the binding of transcription factors (TFs) to DNA, and via recruitment of methyl binding proteins and transcriptional corepressors (8). Therefore, DNA methylation modification represents a link between environmental risk factors and disease progression by influencing gene transcription patterns and, subsequently, organ function. Typically, advancing age, physical inactivity, weight gain and obesity are primary risk factors for the development of T2D (9). In addition, patients suffering from metabolic syndromes with inherent symptoms of glucose intolerance, insulin resistance and abdominal obesity are considered to be in prediabetic state, which may ultimately develop into T2D (10). Previous studies have revealed an association between DNA methylation patterns and alterations in body weight and physical activity. Furthermore, CpG markers of DNA methylation are biomarkers for metabolic syndrome (11–13). Alterations in metabolite levels, including choline, betaine and methionine, are implicated in methylation pathways in the liver (14,15), and choline-associated metabolites have been demonstrated to be implicated in the pathological development of T2D (16). Therefore, DNA methylation has been hypothesized to have an involvement in the pathogenesis of T2D. Furthermore, the negative correlation between increased methylation levels of β-cell specific genes, including pancreatic and duodenal homeobox1 and insulin, and the expression levels of their corresponding proteins, have previously been detected in the pancreatic islets of patients with T2D (17,18). Therefore, there is an incentive to investigate the potential implications of DNA methylation and the associated gene expression pattern modifications with regards to the pathogenic onset of T2D.

T2D is a highly complex multisystem disease. Reduced rates of muscular glycogen synthesis in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes may be induced by defective glucose transport/phosphorylation (19). Furthermore, alterations in mitochondrial gene transcription patterns in skeletal muscle are closely associated with insulin-dependent T2D (20). In addition, the liver is implicated in the regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism, disorders of which frequently occur in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and T2D (21). In the present study, a systematic analysis was performed using publicly-available online genome-wide methylome and transcriptome data from liver tissues from age-matched healthy and obese T2D men, uploaded by Kirchner et al (22), in order to identify disease-associated genes and to better understand T2D at the molecular level. Unlike the study by Kirchner et al (22), the present study aimed to reveal the protein-protein interaction (PPI), TF target and microRNA (miRNA) target networks among the differentially-expressed genes (DEGs), in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of protein function associated with T2D.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

The raw data on gene expression were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), accession no. GSE64998. This dataset, including 21 samples (liver biopsies from six non-obese, eight obese non-diabetic and seven obese T2D men), were collected based on the GPL11532 platform (HuGene-1_1-st) Affymetrix Human Gene 1.1 ST Array [transcript (gene) version]. The data on liver tissues isolated from six non-obese men and seven obese T2D men were extracted. These data were uploaded by Kirchner et al (22); their study was conducted according to the principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki, the regional ethics committee at the Karolinska Insitute (Solna, Sweden) approved the study, and all participants provided informed written consent.

Furthermore, the methylation profile data based on the GPL13534 platform [Illumina Human Methylation 450 BeadChip (HumanMethylation450_15017482)] were downloaded from the GEO database, accession no. GSE65057. The data on liver tissues isolated from seven non-obese controls and nine obese T2D samples were extracted from GSE65057, which were uploaded by Kirchner et al (22).

Data preprocessing

Raw expression profile data in the CEL format were preprocessed using the Oligo package in R (23), which included format transition, missing value interpolation, background correction and data quantile normalization.

The RnBeads Package (24), which used β-values in order to characterize the degree of DNA methylation, was applied for analysis of the downloaded methylation microarray data. Initially, the Infinium probes were manipulated using the Methylumi package (25). Following this, background correction was performed with the normal-exponential convolution using the out-of-band probes method (26), and normalization was performed using the Beta MIxture Quantile dilation method (27). Finally, the probes with a detection value of P>0.01 or bead count <3, located on sex chromosomes or in regions enriched with single nucleotide polymorphisms, were deleted (28).

DEG and differentially-methylated gene (DMG) screening

The empirical Bayes approach in the Limma package (29) was used in order to identify differing levels of DEGs and DMGs between the healthy controls and the obese T2D samples. DEGs were classified as those meeting the criteria of P<0.05 and |log fold change|≥0.5, and DMGs were those with P<0.05. Furthermore, DMGs were mapped to the DEGs in order to identify any overlaps.

Functional and pathway enrichment analyses

The Multifaceted Analysis Tool for Human Transcriptome (www.biocloudservice.com) online tool in BioCloud, a platform storing vast amounts of bioinformatics data and providing analysis software applications, was used to perform Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analyses for the upregulated genes, the downregulated genes and the overlapping genes. KEGG and GO are freely available for public use for the annotation of genes, gene products and gene sequences (30,31). P<0.05 was set as the threshold criterion.

Construction of PPI network

The PPIs among the DEGs were analyzed using the STRING database (32) and the default parameters, and the combined score >0.4 was set as the threshold. Following this, Cytoscape software v3.2.0 (33) was used in order to visualize the PPI network, and connectivity degree analysis was performed in order to screen for hub genes (34). Furthermore, the sub-network involving overlapping genes was extracted from the PPI network.

Construction of the regulatory network for overlapping genes involved in the sub-network

Using the iRegulon plugin (35) in Cytoscape software (33), the TFs targeting the overlapping genes involved in the sub-network were predicted. TF target pairs with a normalized enrichment score >4, calculated with iRegulon plugin, were selected, and the TF target regulatory network was constructed using Cytoscape software (33). In addition, miRNAs targeting the overlapping genes involved in the sub-network were predicted using the WebGestalt tool (36,37). Following the determination of the miRNA target pairs, the miRNA target regulatory network was visualized using Cytoscape software (33).

Data validation of DEGs

A further GSE15653 dataset was used for validation of the DEGs already identified. The GSE15653 dataset was downloaded from GEO, and included four liver tissue samples from obese T2D patients and five healthy controls. Following this, the raw expression profile data in the CEL format from the GSE15653 dataset were preprocessed using the same methods above, and the DEGs in the obese T2D samples were also identified also using the same methods and threshold value used above. Subsequently, the shared upregulated and downregulated DEGs in the GSE15653 and GSE64998 datasets were obtained via Venn analysis, and these identified DEGs were considered to validate the genes identified from GSE64998 dataset.

Results

Identification of DEGs and DMGs

Following analysis of the gene expression profiles of the non-obese and the obese T2D samples, 251 DEGs were detected, including 124 upregulated genes and 127 downregulated genes. Furthermore, 9,698 DMGs (6,021 upregulated genes and 3,677 downregulated genes) were identified in obese diabetic individuals compared with non-obese controls (P<0.05). Following the mapping of the DEGs to the DMGs, a total of 103 overlapping genes were revealed (47 upregulated genes and 56 downregulated genes) in the gene expression profiles.

Functional and pathway enrichment analyses

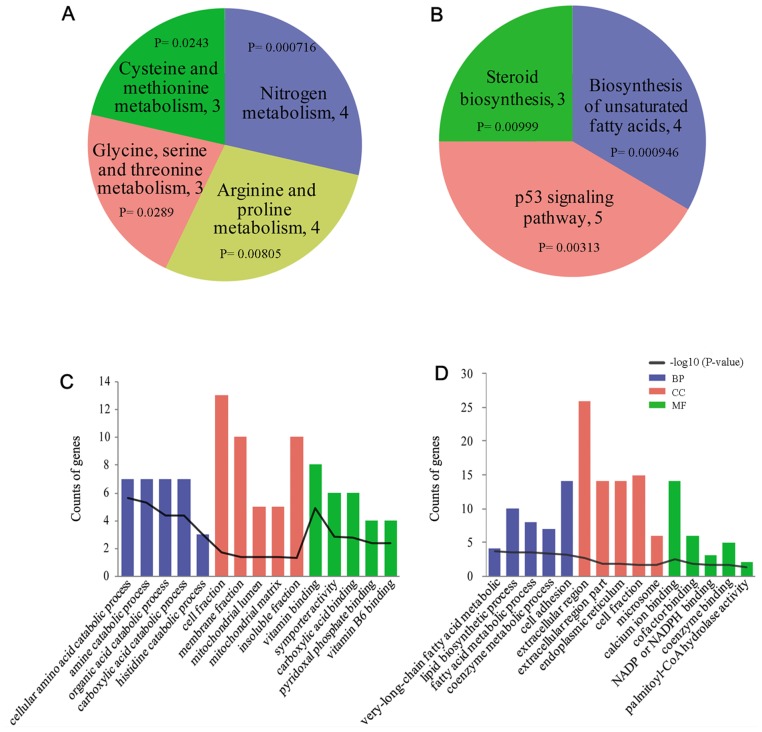

In order to examine the biological functions of abnormal genes in obesity-associated T2D, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed using the previously identified DEGs and the overlapping genes. Fig. 1A and B present the enriched KEGG pathways for the downregulated genes and upregulated genes, respectively; and Fig. 1C and D present the top five prevalent GO terms for the downregulated genes and upregulated genes, respectively. The upregulated genes were most significantly enriched in ‘biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids’ (KEGG pathway; P=9.46×10−4), and the downregulated genes were significantly enriched in KEGG pathways including ‘nitrogen metabolism’ (P=3.52×10−4) and ‘cysteine and methionine metabolism’ (P=2.89×10−2). Furthermore, the 103 overlapping genes were significantly enriched in ‘arginine and proline metabolism’ (KEGG pathway; P=5.53×10−3) and ‘oxidation-reduction reactivity’ (GO term; P=3.52×10−4; Table I).

Figure 1.

Functional and pathway enrichment analyses of upregulated and downregulated genes in patients with T2D. The results of pathway analysis for (A) downregulated genes and (B) upregulated genes in patients with T2D. The top five enriched GO terms for (C) downregulated genes and (D) upregulated genes in patients with T2D. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology; BP, biological process; MF, molecular function; CC, cellular component; NADP (H), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Table I.

KEGG pathways and the top 10 GO BP terms enriched by the overlapping genes.

| A, Pathway | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| hsa00330 | Arginine and proline metabolism | 4 | 5.53×10−3 | GLS2, ALDH18A1, OAT, PRODH |

| B, Biological process | ||||

| ID | Name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| GO:0016053 | Organic acid biosynthetic process | 7 | 3.07×10−4 | ALDH18A1, SDS, SCD, ELOVL2, FASN, LGSN, PRODH |

| GO:0046394 | Carboxylic acid biosynthetic process | 7 | 3.07×10−4 | ALDH18A1, SDS, SCD, ELOVL2, FASN, PRODH |

| GO:0055114 | Oxidation reduction | 13 | 3.52×10−4 | ME1, HSD17B11, TP53I3, ALDH18A1, FMO1, SCD, CYP4F22, FASN, AASS, CYP26A1, PPARGC1A, HPGD, PRODH |

| GO:0009064 | Glutamine family amino acid metabolic process | 4 | 3.57×10−3 | GLS2, ALDH18A1, LGSN, PRODH |

| GO:0006739 | NADP metabolic process | 3 | 3.93×10−3 | ME1, TP53I3, GCK |

| GO:0009084 | Glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process | 3 | 5.53×10−3 | ALDH18A1, LGSN, PRODH |

| GO:0033273 | Response to vitamin | 4 | 6.97×10−3 | CCND1, PDGFA, IGFBP2, SPP1 |

| GO:0007156 | Homophilic cell adhesion | 5 | 7.53×10−3 | RET, CDH15, FAT1, DSG1, CDH23 |

| GO:0007155 | Cell adhesion | 11 | 8.04×10−3 | RET, CDH15, EPDR1, LAMA5, FAT1, DSG1, CPXM2, IL32, CYR61, SPP1, CDH23 |

| GO:0022610 | Biological adhsion | 11 | 8.12×10−3 | RET, CDH15, EPDR1, LAMA5, FAT1, DSG1, CPXM2, IL32, CYR61, SPP1, CDH23 |

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology; BP, biological process.

Construction of PPI network

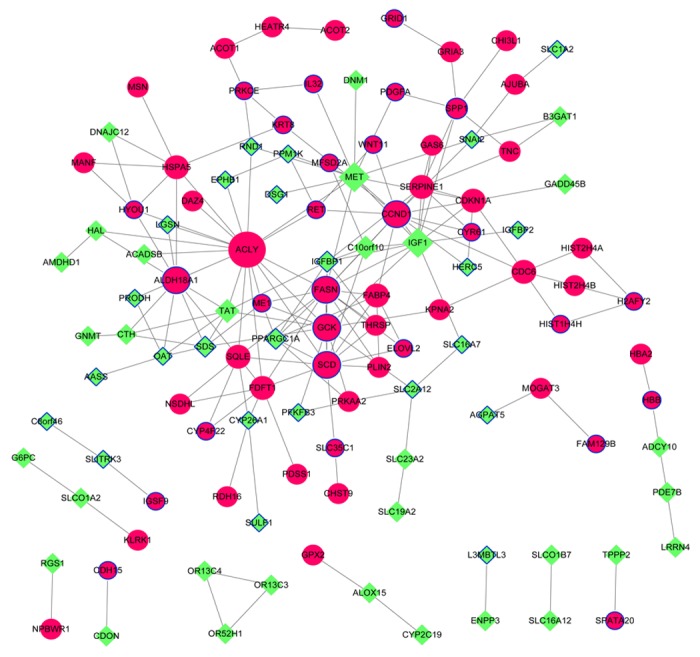

PPIs were determined by STRING database analysis, and a PPI network with 116 nodes and 189 edges was generated for the DEGs (Fig. 2). The top 20 nodes with the highest degrees are detailed in Table II. Notably, fatty acid synthase (FASN), cyclin D1 (CCND1), glucokinase (GCK), stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD), and PPARG coactivator α (PPARGC1A) were all overlapping genes in the PPI network.

Figure 2.

Protein-protein interaction network for the differentially-expressed genes. Red circle nodes represent upregulated genes and the green diamond nodes represent downregulated genes. Overlapping genes between the differentially-expressed and -methylated genes are indicated by surrounding blue borders.

Table II.

Top 20 genes with higher degrees in the protein-protein interaction network.

| Genes | Degree |

|---|---|

| ACLY | 19 |

| FASN | 15 |

| CCND1 | 13 |

| GCK | 12 |

| SCD | 12 |

| MET | 12 |

| IGF1 | 12 |

| ALDH18A1 | 11 |

| SERPINE1 | 9 |

| FDFT1 | 8 |

| SQLE | 8 |

| TAT | 7 |

| HSPA5 | 7 |

| IGFBP1 | 7 |

| CDKN1A | 7 |

| C10orf10 | 6 |

| SDS | 6 |

| SPP1 | 6 |

| FABP4 | 6 |

| PPARGC1A | 6 |

Furthermore, KEGG pathway and GO functional enrichment analyses revealed that the top 20 nodes were predominantly associated with cancer pathways, including ‘p53 signaling pathway’ (KEGG pathway; P=1.36×10−3), and ‘regeneration’ (GO term, P=1.80×10−6; Table III).

Table III.

KEGG pathways and GO BP terms enriched for the top 20 nodes in the protein-protein interaction network.

| A, Pathway | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway ID | Pathway name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| hsa04115 | p53 signaling pathway | 4 | 1.36×10−4 | CDKN1A, CCND1, SERPINE1, IGF1 |

| hsa05218 | Melanoma | 4 | 1.54×10−3 | CDKN1A, CCND1, MET, IGF1 |

| hsa05214 | Glioma | 3 | 1.82×10−2 | CDKN1A, CCND1, IGF1 |

| hsa04510 | Focal adhesion | 4 | 2.75×10−2 | CCND1, MET, IGF1, SPP1 |

| hsa05215 | Prostate cancer | 3 | 3.47×10−2 | CDKN1A, CCND1, IGF1 |

| B, Biological process | ||||

| Pathway ID | Pathway name | Count | P-value | Genes |

| GO:0031099 | Regeneration | 5 | 1.80×10−6 | CDKN1A, CCND1, SERPINE1, IGF1, IGFBP1 |

| GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 8 | 2.25×10−5 | CDKN1A, CCND1, GCK, SQLE, FABP4, IGFBP1, TAT, SPP1 |

| GO:0009725 | Response to hormone stimulus | 6 | 9.15×10−5 | CDKN1A, CCND1, FABP4, IGFBP1, TAT, SPP1 |

| GO:0048545 | Response to steroid hormone stimulus | 5 | 1.03×10−4 | CDKN1A, CCND1, FABP4, TAT, SPP1 |

| GO:0051384 | Response to glucocorticoid stimulus | 4 | 1.41×10−4 | CDKN1A, CCND1, FABP4, TAT |

| GO:0009719 | Response to endogenous stimulus | 6 | 1.46×10−4 | CDKN1A, CCND1, FABP4, IGFBP1, TAT, SPP1 |

| GO:0009991 | Response to extracellular stimulus | 5 | 1.74×10−4 | CDKN1A, CCND1, HSPA5, PPARGC1A, SPP1 |

| GO:0031960 | Response to corticosteroid stimulus | 4 | 1.82×10−4 | CDKN1A, CCND1, FABP4, TAT |

| GO:0010907 | Positive regulation of glucose metabolic process | 3 | 2.82×10−4 | GCK, IGF1, PPARGC1A |

| GO:0010676 | Positive regulation of cellular carbohydrate metabolic process | 3 | 3.13×10−4 | GCK, IGF1, PPARGC1A |

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology.

Construction of TF target network and miRNA target network

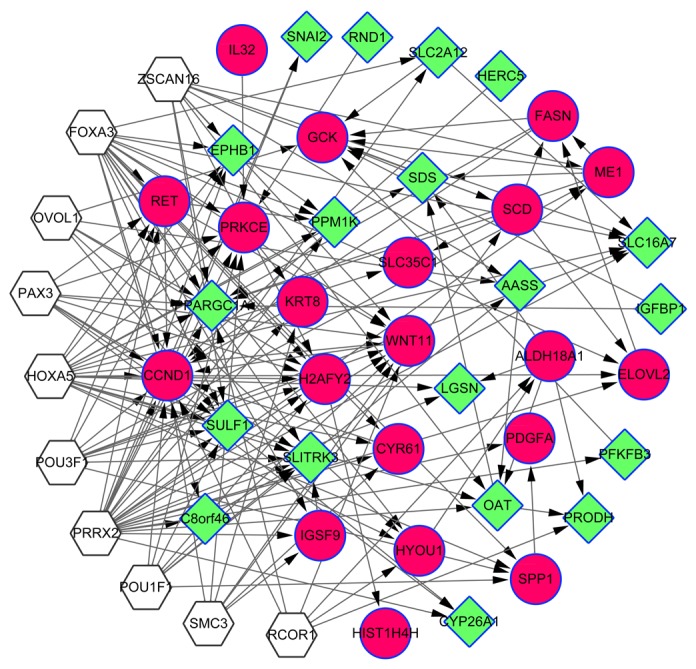

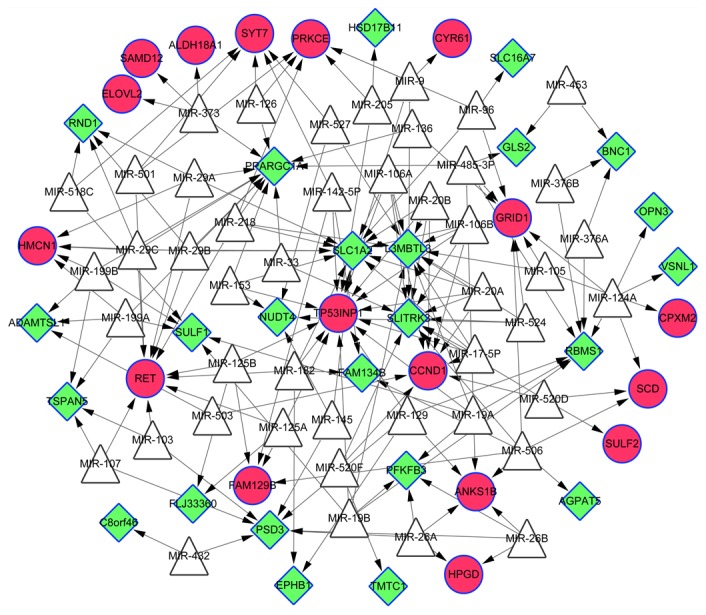

TFs and miRNAs are able to regulate gene expression via modulation of transcriptional activation and stability of mRNA, respectively (38). In the present study, the TF target and miRNA target pairs were predicted based on the overlapping genes involved in the sub-network in order to explore their potential regulatory relationships. A total of 10 TFs were predicted and the TF target network contained 49 nodes and 161 pairs (Fig. 3). The hub genes with the highest degrees are detailed in Table IV. A total of 49 miRNAs, which may be implicated in the abnormal expression of the overlapping genes, were predicted. Following this, a miRNA target network, including 87 nodes and 180 regulatory relationships, was constructed (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the hub genes with the highest degrees were screened for (Table V).

Figure 3.

Transcriptional factor target network. White hexagonal nodes represent the predicted transcription factors. The red circle nodes represent upregulated genes and the green diamond nodes represent downregulated genes. Overlapping genes between the differentially-expressed and -methylated genes are indicated by surrounding blue borders.

Table IV.

Top 12 genes with higher degrees in the transcriptional factor-target regulatory network.

| Genes | Degree |

|---|---|

| CCND1 | 15 |

| PPARGC1A | 11 |

| WNT11 | 11 |

| ZSCAN16 | 10 |

| PRKCE | 9 |

| SULF1 | 9 |

| GCK | 8 |

| RET | 8 |

| SLITRK3 | 8 |

| OAT | 7 |

| SCD | 7 |

| ME1 | 7 |

Figure 4.

MicroRNA target network. White triangle nodes represent the predicted microRNAs. The red cycle nodes represent upregulated genes and the green diamond nodes represent downregulated genes. Overlapping genes between the differentially-expressed and -methylated genes are indicated by surrounding blue borders.

Table V.

Top 14 genes with higher degrees in the microRNA target regulatory network.

| Genes | Degree |

|---|---|

| TP53INP1 | 15 |

| SLC1A2 | 13 |

| PPARGC1A | 12 |

| SLITRK3 | 11 |

| L3MBTL3 | 11 |

| RET | 10 |

| CCND1 | 8 |

| RBMS1 | 7 |

| GRID1 | 7 |

| PSD3 | 7 |

| PRKCE | 6 |

| ANKS1B | 5 |

| SULF1 | 5 |

| HMCN1 | 5 |

Validation of the expression levels of DEGs

A total of 753 upregulated DEGs and 432 downregulated DEGs were identified from the GSE15653 validation dataset using the obesity-associated T2D patients and control samples according to the same method used to identify DEGs in the GSE64998 dataset. By comparing the datasets, it was revealed that among the 124 upregulated DEGs in GSE64998, 15 genes were overlapping genes (e.g., CCND1 and FASN), while among the 127 downregulated DEGs, 20 overlapping genes [e.g., tyrosine immunotransferase (TAT)] were searched. Overlapping DEGs between both datasets were considered to represent preliminary verification of said genes in the GSE64998 dataset (Table VI).

Table VI.

| Common upregulated genes | Common downregulated genes |

|---|---|

| RDH16, SLC39A7, KRT8, AEN, HSPA5, KDM8, ALDH18A1, ATF5, CDHR2, CCND1, SLC35C1, CD151, GAS6, ACOT1, HPS5, APOL3, FASN, CHI3L1, CDKN1A, HBB | SLITRK3, CYP2C19, SLC16A4, CA14, GPR88, OPN3, VIL1, HAL, HERC5, DNAJC12, TAT, PFKFB3, SMPDL3A, SLC19A2, ABCA8 |

Discussion

The high prevalence of T2D and the severity of its associated complications raise great challenges for effective disease management (39). In China, obesity is one of the principal contributory risk factors for T2D development (9). Despite several genes and their regulatory mechanisms being suggested to be implicated in the development of obesity-associated T2D, there remains a requirement for further research in order to uncover the underlying molecular mechanisms implicated in T2D pathogenesis. In the present study, systematic analysis using gene expression patterns and DNA methylation profiles of healthy controls and obese T2D patients was performed in order to reveal hub genes, which may be involved in the pathogenesis of obesity-associated T2D. By performing PPI, TF target and miRNA network analyses, the present study demonstrated that the hub nodes CCND1, PPARGC1A, ATP citrate lyase (ACLY), TAT and FASN may be implicated in the development of obesity-associated T2D.

CCND1 encodes the cyclin D1 protein, and expression of CCND1 has marked periodicity throughout the cell cycle (40). Previous studies have demonstrated an association between the dysregulation of CCND1 expression and T2D (41–43). Microarray and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction data have previously revealed a higher expression pattern of CCND1 in diabetic islets compared with healthy controls (43). In accordance with this, the present study predicted from the GSE64998 and GSE15653 datasets that the expression of CCND1 was upregulated in patients with T2D. In addition, the increased methylation of CCND1 was detectable in patients with T2D (44). However, it has previously been reported that there is no association between the methylation status of CCND1 and its expression (45). Further studies are required to reveal how CCND1 is implicated in T2D pathogenesis.

PPARGC1A is a transcriptional coactivator that modulates genes associated with energy metabolism (46). Numerous studies have demonstrated the link between PPARGC1A, and the development of T2D and associated insulin resistance. Decreased PPARGC1A expression has been detected in cases of insulin resistance (47–49). Furthermore, increased DNA methylation at the site of the PPARGC1A promoter has been detected in skeletal muscle tissue and in the islets of patients with T2D (50). In addition, a negative correlation between the methylation of PPARGC1A and its expression has previously been reported (51). In line with these previous findings, abnormal expression and methylation of PPARGC1A was demonstrated in liver tissues from obese T2D patients in the present study.

In the present study, it was revealed that DNA methylation corresponds with the upregulation of ACLY, FASN, SCD and GCK expression in samples from obese patients with T2D, and had high degrees in the PPI network. ACLY, FASN, GCK and SCD are all enzymes implicated in metabolic processes. ACLY is implicated in the synthesis of cytosolic acetyl-coenzyme (Co)A in numerous tissue types (52). Furthermore, Guay et al (53) demonstrated that ACLY is a fundamental regulator of glucose-induced insulin secretion. FASN, coding for fatty acid synthase, catalyzes the synthesis of palmitate from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA, producing long-chain saturated free fatty acids in the presence of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. Genetic alterations affecting FASN activity may be significantly correlated with T2D via modification of insulin sensitivity (54). A further interpretation of the association of FASN with T2D is that an increase in fatty acids may inhibit insulin signaling and induce metabolic insulin resistance in patients with T2D (55). Furthermore, it has previously been suggested that methylation of the FASN promoter at the 611, 096, 61780, 61778 and 61774 CpG sites may be associated with the progression of NAFLD (56), which is associated with an increased risk of T2D. SCD encodes for the stearoyl-CoA desaturase enzyme that is responsible for fatty acid biosynthesis, which is implicated in lipid-induced insulin resistance, and SCD deficiency increases insulin signaling (57), Furthermore, the expression of SCD is upregulated in diabetic fatty rats (58). In addition, it has been suggested that alterations in SCD expression as a consequence of DNA promoter methylation in morbidly obese patients are associated with the serum levels of free fatty acids (59). Furthermore, the levels of mRNA encoding ACLY, FASN and SCD were markedly upregulated in the livers of Zucker fatty rats, which are commonly used as animal models for fatty liver disease, hepatic insulin resistance and obesity investigations (60). Functional enrichment analysis in the present study revealed that abnormal FASN and SCD expression levels in obesity-associated T2D were predominantly associated with fatty acid biosynthesis metabolism and oxidation reduction. GCK is responsible for the phosphorylation of glucose in order to produce glucose-6-phosphate, which is the first step in the majority of glucose metabolic pathways (61). GCK is predominantly expressed in pancreatic β cells and hepatocytes, and it is implicated the modulation of glucose homeostasis in liver, including glucose synthesis, breakdown and storage (62). It has previously been demonstrated that fluctuations in the expression levels of GCK are a risk factor for the development of T2D (63). Furthermore, elevated levels of CpG island methylation within the GCK gene have been reported in patients with T2D (64). Therefore, the upregulation of ACLY, FASN, SCD and GCK gene expression levels, accompanied by alterations in DNA methylation levels, may be implicated in the development of obesity-associated T2D via regulation of fatty acid and glucose metabolic pathways, and involvement in oxidoreductive and insulin signaling pathways.

The downregulated genes identified in patients with T2D were significantly enriched in the cysteine and methionine metabolic pathways. A previous study reported that cysteine and methionine intake has an association with T2D (65), and that levels of oxidation at cysteine and methionine residues are markedly higher in patients with diabetes compared with nondiabetic individuals (66). The present study revealed that the downregulation of cystathionine γ lyase (CTH) and TAT genes is associated with the metabolism of cysteine and methionine in patients with T2D. Furthermore, a deficiency in CTH may impair H2S biosynthesis and vessel reactivity in T2D (67). TAT is present in the liver and catalyzes the conversion of L-tyrosine into phosphorylated hydroxyphenylpyruvate, and its expression is abnormal in diabetic rats (68). Thus, we hypothesized that the downregulated expression of CTH and TAT altered the DNA methylation levels in obese patients with T2D. However, the influence of their methylation status on the development of T2D has yet to be determined. Further research is required in order to determine whether the alteration in DNA methylation levels in CTH and TAT is correlated with their downregulated expression in T2D.

However, although the present study identified genes with altered expression and DNA methylation in T2D by reanalyzing a published dataset, a number of novel genes were demonstrated to serve potential roles in T2D. These results prove beneficial to the development of a deeper understanding of obesity-associated T2D disease progression. However, the present study had certain limitations. The sample sizes analyzed in GSE64998 and GSE65057 datasets were small. In addition, the association between the expression levels of the DEGs and patterns of DNA methylation were not investigated. Future studies may investigate the correlation between the DEGs and DMGs, and analyze the methylation sites in such DEGs using large sample sizes.

In conclusion, the present study analyzed the mRNA expression and DNA methylation profiles of healthy controls and of patients with obesity-associated T2D using a computational bioinformatics approach. Genes with abnormal expression levels were screened for and the biological functions enriched by these genes were explored. In the present study, several key genes (ACLY, CCND1, PPARGC1A, FASN, GCK, SCD, CTH and TAT) were revealed to be potentially implicated in the progression of insulin resistance in obesity and T2D. However, further experimental studies are required in order to validate the implications of these genes in obesity-associated T2D.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Overseas Study Project of Jiangsu Province for Outstanding Young and Middle-aged Teachers and Principals of Colleges and Universities (grant no. Jiangsu Teachers 2012-13).

References

- 1.DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of type 2 (non-insulin dependent) diabetes mellitus: a balanced overview. Diabetologia. 1992;35:389–397. doi: 10.1007/BF00401208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. World Health Organization: 298. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.King GL. The role of inflammatory cytokines in diabetes and its complications. J Periodontol. 2008;79(8 Suppl):S1527–S1534. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd A, Sawyer W, Hopkinson P. Impact of long-term complications on quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes not using insulin. Value Health. 2001;4:392–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2001.45029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esparza-Romero J, Valencia ME, Urquidez-Romero R, Chaudhari LS, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Ravussin E, Bennett PH, Schulz LO. Environmentally driven increases in type 2 diabetes and obesity in pima indians and non-pimas in mexico over a 15-year period: The maycoba project. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:2075–2082. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414:782–787. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: How the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet. 2003;33(Suppl):S245–S254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klose RJ, Bird AP. Genomic DNA methylation: The mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang C, Li J, Xue H, Li Y, Huang J, Mai J, Chen J, Cao J, Wu X, Guo D, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus incidence in Chinese: Contributions of overweight and obesity. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamant M, Tushuizen ME. The metabolic syndrome and endothelial dysfunction: Common highway to type 2 diabetes and CVD. Curr Diab Rep. 2006;6:279–286. doi: 10.1007/s11892-006-0061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitert MD, Dayeh T, Volkov P, Elgzyri T, Hall E, Nilsson E, Yang BT, Lang S, Parikh H, Wessman Y, et al. Impact of an exercise intervention on DNA methylation in skeletal muscle from first-degree relatives of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:3322–3332. doi: 10.2337/db11-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Zheng S, Wrensch MR, Wiemels JL, Nelson HH, Karagas MR, Padbury JF, Bueno R, et al. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon G, Zheng Y, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Gao T, Joyce B, Zhang W, Guan W, Baccarelli AA, Jiang W, et al. Ultra-high dimensional variable selection with application to normative aging study: DNA methylation and metabolic syndrome. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2017;18:156. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung J, Jung Y, Gill B, Kim C, Hwang KJ, Ju YR, Lee HJ, Chu H, Hwang GS. Metabolic responses to Orientia tsutsugamushi infection in a mouse model. Plos Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e3427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halsted CH, Medici V. Aberrant hepatic methionine metabolism and gene methylation in the pathogenesis and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:959746. doi: 10.1155/2012/959746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svingen GF, Schartum-Hansen H, Pedersen ER, Ueland PM, Tell GS, Mellgren G, Njølstad PR, Seifert R, Strand E, Karlsson T, Nygård O. Prospective associations of systemic and urinary choline metabolites with incident type 2 diabetes. Clin Chem. 2016;62:755–765. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.250761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang BT, Dayeh TA, Kirkpatrick CL, Taneera J, Kumar R, Groop L, Wollheim CB, Nitert MD, Ling C. Insulin promoter DNA methylation correlates negatively with insulin gene expression and positively with HbA(1c) levels in human pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2011;54:360–367. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1967-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang BT, Dayeh TA, Volkov PA, Kirkpatrick CL, Malmgren S, Jing X, Renström E, Wollheim CB, Nitert MD, Ling C. Increased DNA methylation and decreased expression of PDX-1 in pancreatic islets from patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:1203–1212. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cline GW, Magnusson I, Rothman DL, Petersen KF, Laurent D, Shulman GI. Mechanism of impaired insulin-stimulated muscle glucose metabolism in subjects with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2219–2224. doi: 10.1172/JCI119395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asmann YW, Carpenter JE, Short KR, Stump CS, Nair KS. Altered skeletal muscle mitochondrial gene transcriptions in response to insulin infusion in T2D patients. Meeting of the American-Diabetes-Association. 2004;53 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loria P, Lonardo A, Anania F. Liver and diabetes. A vicious circle. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:51–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchner H, Sinha I, Gao H, Ruby MA, Schönke M, Lindvall JM, Barrès R, Krook A, Näslund E, Dahlman-Wright K, Zierath JR. Altered DNA methylation of glycolytic and lipogenic genes in liver from obese and type 2 diabetic patients. Mol Metab. 2016;5:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2363–2367. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assenov Y, Muller F, Lutsik P, Walter J, Lengauer T, Bock C. Comprehensive analysis of DNA methylation data with RnBeads. Nat Methods. 2014;11:1138–1140. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis S, Du P, Bilke S, Triche T, Bootwalla M. Methylumi: Handle Illumina methylation data. R package. 2013 version 2.24.1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Triche TJ, Jr, Weisenberger DJ, Van Den Berg D, Laird PW, Siegmund KD. Low-level processing of Illumina Infinium DNA Methylation BeadArrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M, Bartlett T, Tegner J, Gomez-Cabrero D, Beck S. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:189–196. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YA, Lemire M, Choufani S, Butcher DT, Grafodatskaya D, Zanke BW, Gallinger S, Hudson TJ, Weksberg R. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics. 2013;8:203–209. doi: 10.4161/epi.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smyth GK. In: limma: Linear models for microarray data, In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W, editors. Springer; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris MA, Clark J, Ireland A, Lomax J, Ashburner M, Foulger R, Eilbeck K, Lewis S, Marshall B, Mungall C, et al. The gene ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D258–D261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh036. (Database Issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Von Mering C, Huynen M, Jaeggi D, Schmidt S, Bork P, Snel B. STRING: A database of predicted functional associations between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:258–261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He X, Zhang J. Why do hubs tend to be essential in protein networks? PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janky RS, Verfaillie A, Imrichová H, Van de Sande B, Standaert L, Christiaens V, Hulselmans G, Herten K, Sanchez Naval M, Potier D, et al. iRegulon: From a gene list to a gene regulatory network using large motif and track collections. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Duncan D, Shi Z, Zhang B. WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt): Update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W77–W83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang B, Kirov S, Snoddy J. WebGestalt: An integrated system for exploring gene sets in various biological contexts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W741–W748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hobert O. Gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Science. 2008;319:1785–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1151651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhuo X, Zhang P, Hoerger TJ. Lifetime direct medical costs of treating type 2 diabetes and diabetic complications. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fu M, Wang C, Li Z, Sakamaki T, Pestell RG. Minireview: Cyclin D1: Normal and abnormal functions. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5439–5447. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chowdhury MK, Montgomery MK, Morris MJ, Cognard E, Shepherd PR, Smith GC. Glucagon phosphorylates serine 552 of β-catenin leading to increased expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc in the isolated rat liver. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2015;121:88–96. doi: 10.3109/13813455.2015.1048693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai C, Li N, Song G, Yang Y, Ning X. Insulin-like growth factor 1 regulates growth of endometrial carcinoma through PI3k signaling pathway in insulin-resistant type 2 diabetes. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:3329–3336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taneera J, Fadista J, Ahlqvist E, Zhang M, Wierup N, Renström E, Groop L. Expression profiling of cell cycle genes in human pancreatic islets with and without type 2 diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;375:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karachanak-Yankova S, Dimova R, Nikolova D, Nesheva D, Koprinarova M, Maslyankov S, Tafradjiska R, Gateva P, Velizarova M, Hammoudeh Z, et al. Epigenetic alterations in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Balkan J Med Genet. 2016;18:15–24. doi: 10.1515/bjmg-2015-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker BA, Wardell CP, Chiecchio L, Smith EM, Boyd KD, Neri A, Davies FE, Ross FM, Morgan GJ. Aberrant global methylation patterns affect the molecular pathogenesis and prognosis of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;117:553–562. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu C, Lin JD. PGC-1 coactivators in the control of energy metabolism. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2011;43:248–257. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Semple RK, Crowley VC, Sewter CP, Laudes M, Christodoulides C, Considine RV, Vidal-Puig A, O'rahilly S. Expression of the thermogenic nuclear hormone receptor coactivator PGC-1alpha is reduced in the adipose tissue of morbidly obese subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:176–179. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruschke K, Fishbein L, Dietrich A, Klöting N, Tönjes A, Oberbach A, Fasshauer M, Jenkner J, Schön MR, Stumvoll M, et al. Gene expression of PPARgamma and PGC-1alpha in human omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues is related to insulin resistance markers and mediates beneficial effects of physical training. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:515–523. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammarstedt A, Jansson PA, Wesslau C, Yang X, Smith U. Reduced expression of PGC-1 and insulin-signaling molecules in adipose tissue is associated with insulin resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:578–582. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, Cusi K, Berria R, Kashyap S, Miyazaki Y, Kohane I, Costello M, Saccone R, et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: Potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8466–8471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ling C, Del Guerra S, Lupi R, Rönn T, Granhall C, Luthman H, Masiello P, Marchetti P, Groop L, Del Prato S. Epigenetic regulation of PPARGC1A in human type 2 diabetic islets and effect on insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 2008;51:615–622. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0916-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chypre M, Zaidi N, Smans K. ATP-citrate lyase: A mini-review. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;422:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guay C, Madiraju SR, Aumais A, Joly E, Prentki M. A role for ATP-citrate lyase, malic enzyme and pyruvate/citrate cycling in glucose-induced insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35657–35665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menendez J, Vazquez-Martin A, Ortega FJ, Fernandez-Real JM. Fatty acid synthase: Association with insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cancer. Clin Chem. 2009;55:425–438. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.115352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia Y, Wan X, Duan Q, He S, Wang X. Inhibition of protein kinase B by palmitate in the insulin signaling of HepG2 cells and the preventive effect of archidonic acid on insulin resistance. Front Med China. 2007;1:200–206. doi: 10.1007/s11684-007-0038-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cordero P, Gome-Zuriz AM, Campion J, Milagro FI, Martinez JA. Dietary supplementation with methyl donors reduces fatty liver and modifies the fatty acid synthase DNA methylation profile in rats fed an obesogenic diet. Genes Nutr. 2013;8:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s12263-012-0300-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dobrzyn P, Jazurek M, Dobrzyn A. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase and insulin signaling-what is the molecular switch? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voss MD, Beha A, Tennagels N, Tschank G, Herling AW, Quint M, Gerl M, Metz-Weidmann C, Haun G, Korn M. Gene expression profiling in skeletal muscle of Zucker diabetic fatty rats: Implications for a role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 in insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2622–2630. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwenk RW, Jonas W, Ernst SB, Kammel A, Jähnert M, Schürmann A. Diet-dependent alterations of hepatic Scd1 expression are accompanied by differences in promoter methylation. Horm Metab Res. 2013;45:786–794. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karahashi M, Hirata-Hanta Y, Kawabata K, Tsutsumi D, Kametani M, Takamatsu N, Sakamoto T, Yamazaki T, Asano S, Mitsumoto A, et al. Abnormalities in the metabolism of fatty acids and triacylglycerols in the liver of the goto-kakizaki rat: A model for non-obese type 2 diabetes. Lipids. 2016;51:955–971. doi: 10.1007/s11745-016-4171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.German MS. Glucose sensing in pancreatic islet beta cells: The key role of glucokinase and the glycolytic intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1781–1785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matschinsky FM. Glucokinase, glucose homeostasis, and diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2005;5:171–176. doi: 10.1007/s11892-005-0005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muller YL, Piaggi P, Hoffman D, Huang K, Gene B, Kobes S, Thearle MS, Knowler WC, Hanson RL, Baier LJ, Bogardus C. Common genetic variation in the glucokinase gene (GCK) is associated with type 2 diabetes and rates of carbohydrate oxidation and energy expenditure. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1382–1390. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3234-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang L, Ye H, Hong Q, Wang L, Wang Q, Wang H, Xu L, Bu S, Zhang L, Cheng J, et al. Elevated CpG island methylation of GCK gene predicts the risk of type 2 diabetes in Chinese males. Gene. 2014;547:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Valente A, Bicho M, Duarte R, Raposo JF, Costa HS. Dietary sodium intake related with cysteine and methionine in type 2 diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235:e108–e109. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.05.293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen HJ, Yang YF, Lai PY, Chen PF. Analysis of chlorination, nitration, and nitrosylation of tyrosine and oxidation of methionine and cysteine in hemoglobin from type 2 diabetes mellitus patients by nanoflow liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2016;88:9276–9284. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Velmurugan GV, White C. Cystathionine gamma-lyase deficiency impairs H2S biosynthesis and vessel reactivity in type-2 diabetes. FASEB J. 2013;27(1 Suppl):S1091–S1093. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hotta N, Kakuta H, Fukasawa H, Koh N, Sakakibara F, Nakamura J, Hamada Y, Wakao T, Hara T, Mori K, et al. Effect of a potent new aldose reductase inhibitor, (5-(3-thienyltetrazol-1-yl)acetic acid (TAT), on diabetic neuropathy in rats. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1995;27:107–117. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(95)01033-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]