Abstract

Clostridium difficile disease has recently increased to become a dominant nosocomial pathogen in North America and Europe, although little is known about what has driven this emergence. Here we show two epidemic ribotypes (RT027 and RT078) have acquired unique mechanisms to metabolize low concentrations of the disaccharide trehalose. RT027 strains contain a single point mutation in the trehalose repressor that increases this ribotype’s sensitivity to trehalose by >500 fold. Furthermore, dietary trehalose increases virulence of a RT027 strain in a mouse model of infection. RT078 strains acquired a cluster of four genes involved in trehalose metabolism, including a PTS permease that is both necessary and sufficient for growth on low concentrations of trehalose. We propose that the implementation of trehalose as a food additive into the human diet, shortly before the emergence of these two epidemic lineages, helped select for their emergence and contributed to hypervirulence.

Whole genome sequencing analysis of C. difficile ribotype 027 (RT027) strains demonstrated that two independent lineages emerged in North America from 2000-2003.1 Comparison with historic, pre-epidemic, RT027 strains showed that both epidemic lineages acquired a mutation in the gyrA gene, leading to increased resistance to fluoroquinolone antibiotics. While the development of fluoroquinolone resistance (FQR) has almost certainly played a role in the spread of RT027 strains, FQR has also been observed in non-epidemic C. difficile ribotypes and identified in strains dating back to the mid-1980s.2,3 Thus, other factors likely contributed to the emergence of epidemic RT027 strains.

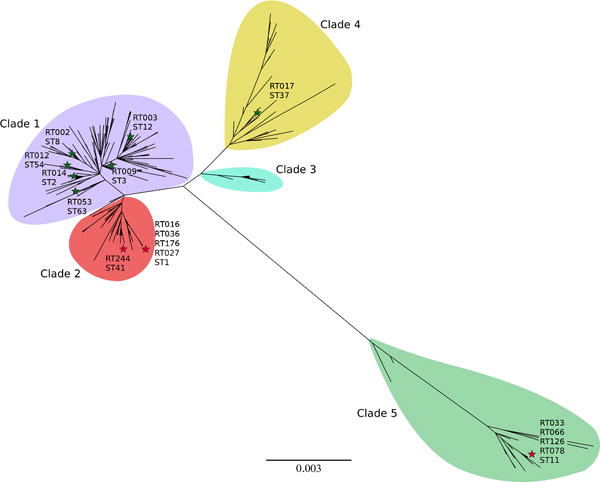

The prevalence of a second C. difficile ribotype, RT078, increased 10-fold in hospitals and clinics from 1995-2007 and was associated with increased disease severity.4 However, the mechanisms responsible for increased virulence remain unknown.5–8 It is noteworthy that RT027 and RT078 lineages are phylogenetically distant from one another (Extended Data Fig. 1), indicating that the evolutionary changes leading to concurrent increases in epidemics and disease severity might have emerged by independent mechanisms.9

Epidemic RT027 and RT078 strains can grow on low concentrations of trehalose

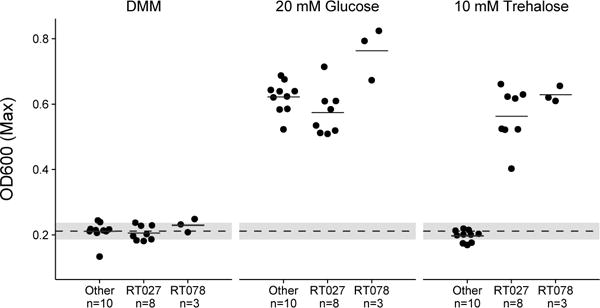

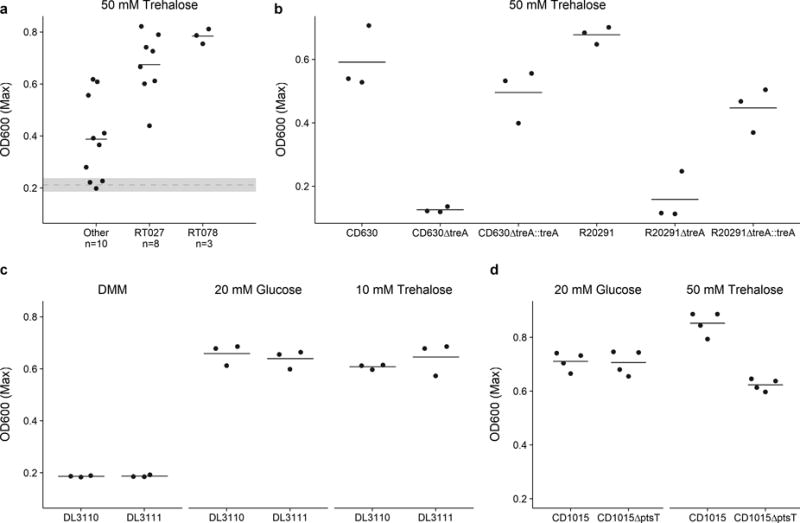

Ribotype 027 strains exhibit a competitive advantage over non-RT027 strains in vitro and in mouse models of CDI.10 To investigate potential mechanisms for increased fitness, we examined carbon source utilization in an epidemic RT027 isolate (CD2015) using the Biolog 96-well Phenotype MicroArray carbon source plates (see Methods and Extended Data Table 1). Out of several carbon sources identified that supported CD2015 growth, we found the disaccharide trehalose increased the growth yield of CD2015 by approximately 5-fold compared to a non-RT027 strain. To examine the specificity of enhanced growth on trehalose across C. difficile lineages, 21 strains encompassing 9 ribotypes were grown on a defined minimal medium (DMM) supplemented with glucose or trehalose as the sole carbon source. All C. difficile strains grew robustly with 20 mM glucose, however, only epidemic RT027 (n=8) and RT078 (n=3) strains exhibited enhanced growth on an equivalent trehalose concentration (10 mM; Fig. 1). Increasing the trehalose concentration to 50 mM enabled growth in most ribotypes (Extended Data Fig. 2a).

Figure 1. Only RT027 and 078 strains show enhanced growth on 10 mM trehalose.

Dashed grey line and band indicate mean growth in DMM without a carbon source and s.d. for all samples (n=21). Solid lines are mean growth yield (OD600) for groups: Non-RT027/078 (n=10), RT027 (n=8), and RT078 (n=3). All points represent biologically independent samples.

Molecular basis for RT027 growth on low levels of trehalose

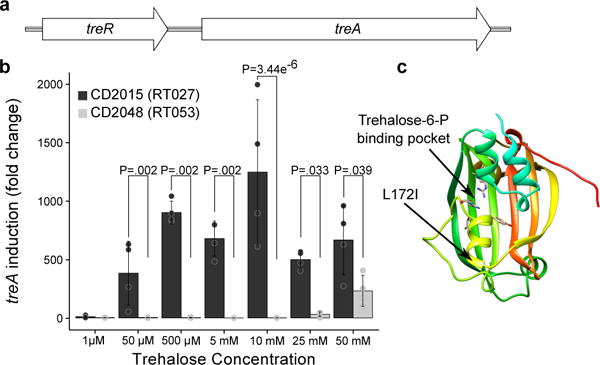

To identify the genetic basis for enhanced trehalose metabolism, we compared multiple C. difficile genomes. All C. difficile genomes encode a putative phosphotrehalase enzyme (treA) preceded by a transcriptional repressor (treR) (Fig. 2a). Phosphotrehalase enzymes metabolize trehalose-6-phosphate into glucose and glucose-6-phosphate. To test whether treA was essential for trehalose metabolism, we generated treA deletion mutants in the RT027 strain R20291 (R20291ΔtreA) and the RT012 strain CD630 (CD630ΔtreA) and grew them in DMM supplemented with 50 mM trehalose. The lack of treA prevented growth in both knockout strains that could be complemented by plasmid expression of treA (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Thus, treA is required to metabolize trehalose.

Figure 2. treA is responsible for trehalose metabolism.

a, Trehalose metabolism operon found in all C. difficile strains; consisting of a phosphotrehalase (treA) and its transcriptional regulator (treR). b, RT027 strains strongly induce treA at 50 μM trehalose and at a significantly higher level than non-RT027 strains (n=4 biologically independent samples per trehalose concentration/strain). Bars are average fold increase, error bars are s.d.; p values derived from t-test (2-tailed) and Holm corrected for multiple comparisons. c, Structure of TreR monomer highlighting proximity of L172I mutation to trehalose-6-P binding pocket.

We next asked if RT027 strains have altered regulation of the treA gene when compared to other ribotypes. To test this hypothesis and determine the minimum level of trehalose required to activate treA expression, we grew CD2015 (RT027) and CD2048 (RT053) and exposed them to increasing amounts of trehalose. We found that the RT027 strain turned on treA expression at 50 μM trehalose, a concentration 500-fold lower than that required to turn on treA in RT053 (Fig. 2b). To confirm this phenotype, we took four RT027 strains and four non-RT027 strains and measured expression of treA in a single trehalose concentration. Again, RT027 strains exhibited significantly higher treA expression than all other ribotypes (P=0.029, Extended Data Fig. 3). These results support the idea that RT027 strains are exquisitely sensitive to low concentrations of trehalose.

Sequence alignment of the trehalose operon across 1,010 sequenced C. difficile strains revealed a conserved single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within the treR gene of all RT027 strains (TreRRT027) (Extended Data Fig. 4a). The SNP encodes an L172I amino acid substitution near the predicted effector (trehalose-6-phosphate) binding pocket of TreR (Fig. 2c), a site that is highly conserved across multiple species (93.9% conservation, Extended Data Fig. 4b). This SNP is found not only in every RT027 strain sequenced to date, but is also present in a newly isolated fluoroquinolone sensitive ribotype (RT244) that has caused community-acquired epidemic outbreaks in Australia11,12 and other ribotypes very closely related to RT027, such as RT176 which has caused epidemic outbreaks in the Czech Republic and Poland.13,14 Like RT027 strains, the RT244 strains DL3110 and DL3111 can grow on 10 mM trehalose (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

To determine the types of spontaneous mutations that lead to enhanced trehalose utilization, we cultivated several non-RT027/RT078 strains under low trehalose concentrations in minibioreactors.10 After 3 days of continuous cultivation, 13 independent spontaneous mutants capable of growing on low concentrations (< 10 mM) of trehalose were isolated. All thirteen mutants contained either nonsense or missense mutations in the treR gene (Extended Data Table 2).

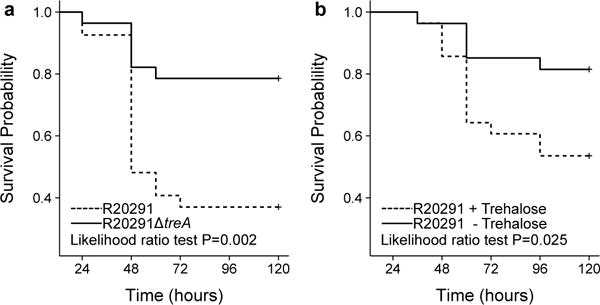

Impact of trehalose metabolism on disease severity

To test whether the ability of C. difficile RT027 strains to metabolize trehalose impacts disease severity, we performed two different experiments. In the first, humanized microbiota mice were challenged with 104 spores of either R20291 (RT027, n=27) or R20291ΔtreA (n=28). Following infection, trehalose (5 mM) was provided ad libitum in the drinking water and disease progression monitored. The R20291ΔtreA mutant demonstrated a dramatic decrease in mortality (33.3 vs 78.6%) when compared to R20291 (78% lower risk with R20291ΔtreA; hazard ratio, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.59; P=0.003, likelihood ratio test P=0.002 (Fig. 3a). In the second experiment, we infected two groups of humanized microbiota mice with RT027 strain R20291. One group received 5 mM trehalose in water as well as a daily gavage of 300 mM trehalose (n=28) to mimic a dose expected in a meal for humans, whereas the control group (n=27) received a water control. Trehalose addition was found to cause increased mortality compared to the RT027 infected mice without dietary trehalose (3-fold increased risk with trehalose; hazard ratio, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.09 to 9.42; P=0.035, likelihood ratio test P=0.026, Fig 3b). Combined, these results show that metabolism of dietary trehalose can contribute to disease severity of RT027 C. difficile strains.

Figure 3. Trehalose metabolism increases virulence.

a, Mice Infected with R20291ΔtreA (n=27 animals) have significantly attenuated risk of mortality when compared to mice infected with R20291 (n=28 animals) (78% lower risk with ΔtreA mutant; hazard ratio, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.59; P=0.003). b, Mice infected with R20291 (RT027) have a significantly higher risk of mortality when trehalose is supplemented in the diet (n=28 animals) than those with no trehalose supplementation (n=27 animals) (3-fold increased risk with trehalose; hazard ratio, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.09 to 9.42; P=0.035). All statistical tests were 2 sided.

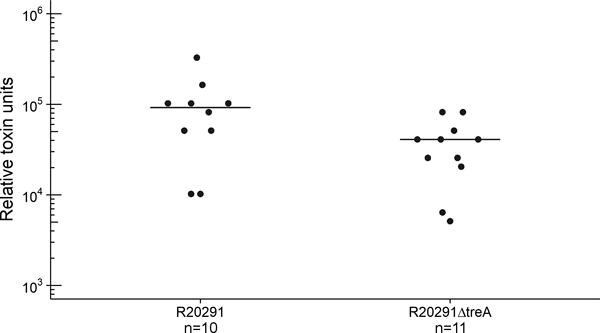

To identify the cause of increased disease severity when trehalose is present, we challenged mice with either R20291 or R20291ΔtreA and provided 5 mM trehalose ad libitum in the drinking water. Forty-eight hours post challenge, C. difficile load and toxin levels were measured. Over two independent experiments, no significant difference in C. difficile numbers were observed, however, a significant increase in relative toxin B levels was detected (median 9.2 X104, IQR 5.1 × 104−1.0 × 105 Vs median 4.1 × 104, IQR 2.3 × 104−4.6 × 104, p=.0268, Extended Data Fig. 5). This increased toxin production could contribute to increased disease severity.

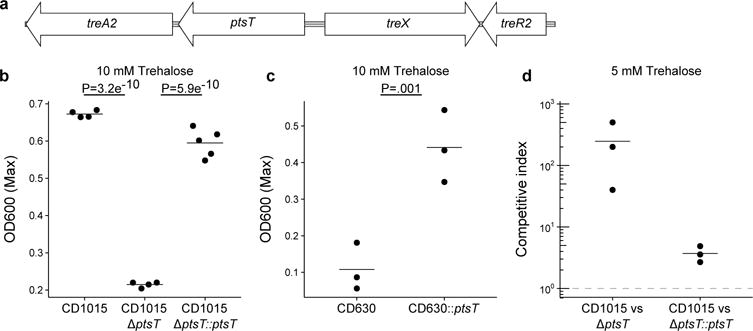

Molecular basis for RT078 growth on low levels of trehalose

Molecular basis for RT078 Unlike RT027, RT078 strains do not possess the TreR L172I substitution or other conserved SNPs in the treRA operon. To identify sequences of potential relevance to trehalose metabolism, we performed whole genome comparisons. A four-gene insertion was found in all RT078 strains sequenced to date, annotated to encode a second copy of a phosphotrehalase (TreA2, sharing 55% amino acid identity with TreA), a potential trehalose specific PTS system IIBC component transporter (PtsT), a trehalase family protein that is a putative glycan debranching enzyme (TreX), and a second copy of a TreR repressor protein (TreR2, sharing 44% amino acid identity with TreR) (see Fig. 4a). Genomic comparison of publicly available C. difficile genomes revealed the four-gene insertion was present in RT078 and the closely related RT033, RT045, RT066, and RT126 ribotypes and absent from reference genomes of any other C. difficile lineage (Extended Data Fig. 6).

Figure 4. ptsT enables enhanced trehalose metabolism.

a, Structure of horizontally acquired trehalose metabolism module found in RT078 and closely related strains. b, Deletion of the trehalose transporter from a clinical RT078 strain (CD1015) ablates its ability to grow on 10 mM trehalose. Expression of ptsT from an inducible plasmid restores growth of CD1015ΔptsT on 10 mM trehalose, (CD1015, n=4; CD1015ΔptsT, n=4; CD1015ΔptsT::ptsT, n=5). c, Expressing ptsT from an inducible plasmid enables enhanced growth of CD630 (RT012) on 10 mM trehalose (CD630 n=3; CD630::ptsT n=3). d, The ptsT provides a competitive advantage in complex microbial communities. Dashed grey line (CI = 1) indicates equal fitness of the competing strains, points above this line represent out-competition by CD1015. All points (Fig 4b-d) represent biologically independent samples, bars are mean, p values derived from t-test (2-tailed) and Holm corrected for multiple comparisons where appropriate.

To test whether the newly acquired transporter (ptsT) was responsible for enhanced trehalose metabolism, a ptsT deletion mutant was constructed in a RT078 (CD1015) strain. This strain was unable to grow on DMM supplemented with 10 mM trehalose (Fig. 4b), but retained the ability to grow in medium supplemented with 50 mM trehalose (Extended Data Fig. 2d). The growth defect in this deletion mutant (CD1015ΔptsT) was directly due to the lack of ptsT since expression of ptsT from an inducible promoter could complement growth on 10 mM trehalose (Fig 4b).

We next tested if ptsT was sufficient to confer enhanced trehalose utilization in a non-ribotype 078 strain, which fails to grow under low trehalose concentrations. To this end, ptsT was expressed from an inducible promoter in strain CD630 (RT012). Expression of ptsT was sufficient to allow growth of CD630 in DMM supplemented with 10 mM trehalose (Fig. 4c). Taken together, we conclude that ptsT is both necessary and sufficient to support growth on low concentrations of trehalose.

To test whether the expression of ptsT could confer a fitness advantage, CD1015 (RT078) was competed against its isogenic CD1015ΔptsT mutant in a human faecal minibioreactor (MBRA) model of CDI.10 Following clindamycin treatment of MBRA communities to enable infection, CD1015 and CD1015ΔptsT strains were added together to each reactor and levels monitored over time. Remarkably, the CD1015 strain was found to be significantly more efficient at competing in vivo in the presence of a complex microbiota than the CD1015ΔptsT mutant (mean competitive index of 246 on day 7). To ensure the CD1015ΔptsT loss was due to the absence of ptsT, CD1015 was competed against the CD1015ΔptsT mutant complemented with ptsT from an inducible vector. After 5 days continuous competition, the wild-type RT078 had a mean competitive index of just 3.7 (Fig. 4d). Hence, ptsT provides a competitive fitness advantage to RT078 strains.

Significant amounts of dietary trehalose are observed in the distal gut

Despite the presence of a localized brush border trehalase enzyme in the small intestine, human studies suggest that high levels of trehalose consumption can result in significant amounts reaching the distal ileum and colon.15–17 To demonstrate that a significant amount of dietary trehalose can survive transit through the small intestine, we gavaged mice with 100 μl (300 mM) trehalose (equivalent to the suggested concentration in ice cream) and measured trehalose levels in the cecum over time. Using clinical C. difficile strains as biosensors, we found the level of trehalose to be sufficient to activated treA gene expression in the RT027 strain CD2015 but not in RT053 strain CD2048 (Fig 5a). To test whether we could detect a low dietary amount of trehalose, we gavaged antibiotic treated mice with 100 μl (5 mM) trehalose and measured treA activation in these same strains. Again, the RT027 strain showed significant treA activation (Fig. 5b). Finally, to determine if trehalose is bioavailable in humans at sufficient levels to be utilized by epidemic C. difficile isolates, we tested ileostomy effluent from three anonymous donors consuming their normal diets. In 2 of 3 samples, treA expression was strongly induced in the RT027 strain CD2015 but not in the RT053 strain CD2048 (Fig. 5c), supporting the notion that levels of trehalose found in food is sufficient to be utilized by epidemic C. difficile strains.

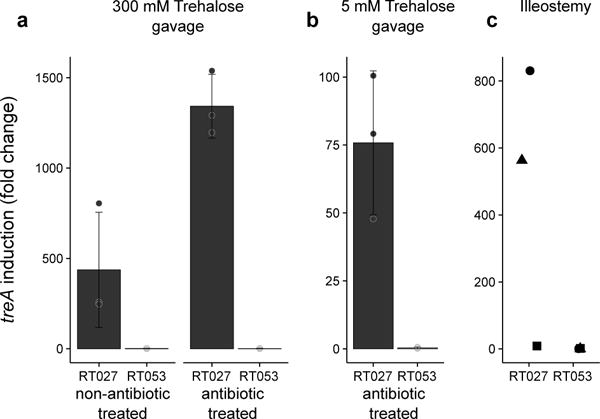

Figure 5. Trehalose can be detected in murine cecum and human ileostomy fluid.

a, Twenty minutes post gavage, trehalose reaches high enough levels in the murine cecum to turn on expression of treA in RT027 but not non-RT027 in both non-antibiotic and antibiotic treated mice (n=3 animals per trehalose concentration/strain). b, trehalose can be detected by RT027 but not non-RT027 in the cecum of antibiotic treated mice gavaged with just 100 μl 5 mM trehalose (n=3 animals per group). c, RT027 strains can detect trehalose in 2/3 human ileostomy fluid samples tested from patients eating a normal (no deliberate trehalose addition) diet. Points represent biologically independent replicates, bars are average fold increase, error bars are s.d.

Discussion

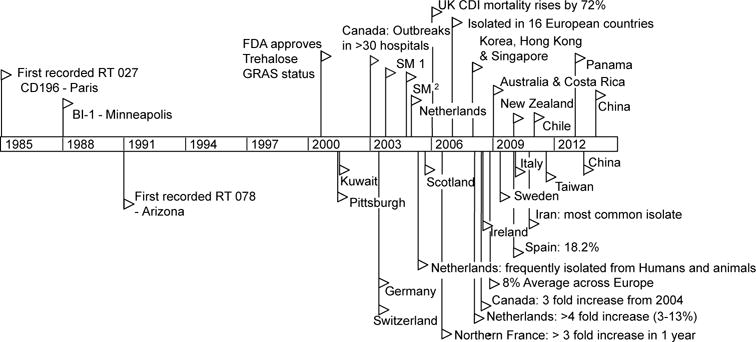

Containing an α,α-1,1-glucoside bond between two α-glucose units, trehalose is a non-reducing and extremely stable sugar, resistant to both high temperatures and acid hydrolysis. Although considered an ideal sugar for use in the food industry, the use of trehalose in the US and Europe was limited prior to 2000 due to high cost of production (~$700 Kg−1). The innovation of a novel enzymatic method for low cost production from starch made it commercially viable as a food supplement (~$3 Kg−1).18 Granted GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status by the FDA in 2000 and approved for use in food in Europe in 2001, reported expected usage ranges from concentrations of 2%-11.25% for foods including pasta, ground beef, and ice cream. The widespread adoption and use of trehalose in the diet coincides with the emergence of both RT027 and RT078 outbreaks (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Timeline of trehalose adoption and spread of RT027 & RT078 lineages.

Flags indicate reported outbreaks or first reports of ribotype 027 (top) or 078 (bottom) in PubMed. † Stoke Mandeville outbreaks.

Several lines of evidence support that dietary trehalose has participated in the spread of epidemic C. difficile ribotypes. First, the ability of RT027 and RT078 strains to metabolize trehalose was present prior to epidemic outbreaks. The earliest retrospectively recorded RT027 isolate was the non-epidemic strain CD196, isolated in 1985 in a Paris hospital.19 Three years later in 1988, another non-epidemic strain RT027 (BI1) was isolated in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Both isolates, in addition to every RT027 strain sequenced to date, contain the L172I substitution in TreR. RT078 strains were also present in humans prior to 2001, but epidemic outbreaks were not reported until 2003.4 Second, RT027 and RT078 lineages are phylogenetically distant clades of C. difficile, yet have convergently evolved distinct mechanisms to metabolize low levels of trehalose. Third, increased disease severity of a RT027 strain that can metabolize trehalose in our CDI mouse model is consistent with increased virulence of RT027 and RT078 ribotypes observed in patients. Fourth, the ability to metabolize trehalose at lower concentrations confers a competitive growth advantage in the presence of a complex intestinal community. Finally, levels of trehalose in ileostomy fluid from patients eating a normal diet are sufficiently high to be detected by RT027 strains. Based on these observations, we propose the widespread adoption and use of the disaccharide trehalose in the human diet has played a significant role in the emergence of these epidemic and hypervirulent strains.20

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth

A full list of strains can be found in Extended Data Table 3. Carbon source utilization of CD630 (RT012) and CD2015 (clinical RT027) was carried out using Biolog Phenotypic Microarray plates. Growth studies were carried out under anaerobic conditions (5% hydrogen, 90% nitrogen, 5% carbon dioxide). Strains were cultured in overnight in BHI media (Difco) supplemented with 0.5% w/v yeast extract. Growth assays utilized a defined minimal medium (DMM) as described previously21 supplemented with either trehalose or glucose as indicated. Anhydrous tetracycline was used at 500 ng/ml to induce expression of ptsT or treA from ectopic expression vectors.

Comparative genomics

To identify unique functional features in RT078 strains, we reviewed publicly available C. difficile genomes covering all phylogenetic lineages9 using a tool based on BLASTX comparisons of protein annotations.22 The genomes included in the analysis were PCR RT012 (strain 630, lineage I), RT027 (R20291, lineage II), PCR RT017 (CF5, M68 lineage IV), and RT078 (QCD-23m63, CDM120 lineage V).

Genetic manipulation of C. difficile

Inactivation of treA in CD630 was accomplished by group-II intron directed insertion as previously described.23 Primers were designed to target intron to insert at bp 177 of treA of CD630 (IBS1.2, EBS1, and EBS2; All primers are described in Extended Data Table 3). The resulting treA insertion-deletion mutant was verified by PCR using primer pair (CR064-CR065) designed to flank the treA insertion site, resulting in a 350bp product for the wild-type gene and a 2.4 kbp product for the gene knockout.

Clean deletions in R20291 and CD1015 were performed using a pyrE allelic exchange system as described previously.24 This is the first case of the pyrE allelic exchange system being used in the RT078 lineage and required generation of CD1015ΔpyrE prior to further deletions. Complementation of treA and ptsT was carried out using an anhydrous tetracycline inducible system as described previously.25 All plasmid conjugations into C. difficile strains were carried out with E. coli SD46. Cloning was accomplished with a combination of restriction digest and ligase cycling reactions as described previously.26 Primers and detailed plasmid maps for construction of knockout strains are available at the links provided in Extended Data Table 3.

Quantitative real-time PCR with reverse transcription

Strains were grown overnight and subcultured 1:50 into DMM supplemented with 20 mM succinate. Upon reaching an OD600 of 0.2-0.3, indicated concentrations of trehalose were added to the culture. After 30 minutes incubation, C. difficile cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in RNALater solution (Invitrogen), and stored at −80°C. Cells were resuspended in 1 ml RLT buffer (Qiagen RNeasy Kit) and lysed by bead beating (2 × 1 min) at 4°C followed by RNA extraction per manufacturers’ instruction. cDNA was synthesized using Invitrogen Superscript III reverse transcriptase following the recommended protocol. Quantitative PCR reactions were performed in triplicate using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ABI) with either C. difficile 16s (JP048-JP049) or treA (CR045-CR046) specific primers. Standard curves of cDNA were run to determine primer efficiencies and calculated as per Pfaffl et al.27 Expression of treA was determined using an average of triplicate CT values from each biological sample.

Mouse model of CDI

Humanized microbiota mice (HMbmice) were derived from an initial population of germ free C57bl/6 mice stably colonized with human gut microbiota and validated for use as a model of CDI.28 HMbmice aged 6-8 weeks of both sexes were treated with a five-antibiotic cocktail consisting of kanamycin (0.4 mg ml−1), gentamicin (0.035 mg ml−1), colistin (850 U ml−1), metronidazole (0.215 mg ml−1), and vancomycin (0.045 mg ml−1)) administered ad libitum in drinking water for 4 days. Water was switched to antibiotic-free sterile water and 24 hrs later mice were administered an intra-peritoneal (IP) injection of clindamycin (10 mg kg−1). After a further 24 hrs, mice were challenged with 104 C. difficile spores by oral gavage. Sterile drinking water containing 5 mM trehalose was provided ad libitum (for the +/- trehalose study, mice were administered an additional 100 μl oral gavage of 300 mM trehalose daily) and mice were monitored for signs of disease.

In a separate experiment to determine C. difficile colonization load and toxin production, mice were euthanized 48 hours following challenge with either R20291 or R20291ΔtreA. C. difficile levels in cecal contents were determined by qPCR of toxin genes.10 Relative toxin levels were assessed using a Vero Cell rounding assay.10 Sample sizes for all experiments were determined using power analysis based upon prior experimental data. No randomization of animals was performed; however, all groups were checked to ensure no significant difference in the age, weight or sex of mice between groups prior to starting experiments. All animal use was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Baylor College of Medicine (Protocol no. AN-6675).

Detection of trehalose in cecal contents and human ileostomy fluid

Antibiotic treated groups were pre-treated with the 5-antibiotic cocktail for 3 days. Mice were gavaged 100 μl of 5 mM trehalose, 300 mM trehalose or water. Twenty minutes post gavage mice were euthanized, cecal contents harvested and vigorously mixed with 2 volumes/weight ice cold DMM (no carbohydrate). Supernatant was separated by centrifugation, filter sterilized, and reduced in an anaerobic chamber overnight prior to use. Ileostomy effluent from three anonymous donors was self-collected into sterile containers and stored at −20°C until thawed, filter sterilized, and used for assay.

Strains were grown overnight and subcultured 1:50 into DMM supplemented with 20 mM succinate. Upon reaching an OD600 of 0.2-0.3 cells were collected via centrifugation and resuspended in ~300 μL cecal or ileostomy fluid and incubated anaerobically for 30 minutes. Cells were then centrifuged and resuspended in RNAlater (Invitrogen) prior to qRT-PCR analysis.

Bioreactor model for ribotype 078 ΔptsT competition

Faecal communities were established in continuous-flow minibioreactor arrays as previously described10 using bioreactor defined medium29 without starch (BDM4). Communities were disrupted by addition of clindamycin (250 μg ml−1) continuously supplied in the medium for four days. Following clindamycin treatment, communities were supplied BDM4 without clindamycin supplemented with trehalose (5 mM final concentration, BDM4tre). After 1 day of growth in BDM4tre, to allow washout of clindamycin, communities were challenged with a mixture of exponentially growing CD1015 strains (RT078 wt and ΔptsT). The competitive index (CI) was determined by dividing the proportion of wildtype (wt) cells at the end of the competition by the proportion at the start. The CI of wt:ΔptsT strains was determined by qPCR. The CI of wt vs CD1015ΔptsT::ahTCptsT was calculated by selective plating.

Isolation of spontaneous treR mutants

C. difficile strains were inoculated into continuous-flow minibioreactor arrays as previously described10 using bioreactor defined medium29 without starch (BDM4) supplemented with 5mM trehalose (BDM4tre). Every 24 hours after the start of the experiment 200 μL PBS with containing 100 mM trehalose was spiked into each minibioreactor. The reactors were sampled daily, serially diluted and plated to DMM agar supplemented with 10 mM trehalose. Resulting colonies were streak purified and the ability to grow on low trehalose (10 mM) verified on plates and in broth culture. The treR gene was sequenced and compared to the isogenic parent strain.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using R (v. 3.3.2). The Students two sample t-test (2-tailed) was used for comparisons of continuous variables between groups with similar variances; Welch two sample t-test (2-tailed) was used for comparisons of continuous variables between groups with dissimilar variances. P values from multiple comparisons were corrected using the Holm method.30 Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction was used for the toxin assay where data is non-normal. Fold change data from treA gene expression experiments were log-normalized prior to statistical analysis. Data were visualized using individual data points and group means. The cox proportional hazards model and likelihood ratio tests were used to test significant differences in survival distributions among C. difficile-challenged groups of animals.

Collection of human bio-specimens

For faecal samples, live subjects who were self-described as healthy and had not consumed antibiotics within the previous two months were recruited to provide faecal samples for human faecal bioreactor experiments. Informed consent was obtained prior to collection of samples and no identifying information was obtained along with the sample. Faecal samples were collected in sterile containers, transported to the laboratory on ice in the presence of anaerobic gas packs (BD Biosciences) within 16 hrs of collection, manually homogenized in an anaerobic environment, aliquoted into anaerobic tubes, sealed and stored at −80°C until use. Subjects who had ileostomies placed due to a previous, undisclosed illnesses were recruited to provide ileostomy effluents. Informed consent was obtained prior to collection of samples and no identifying information was obtained along with the sample. After transfer from the ostomy bag to a sterile collection container, ileostomy samples were transported to the laboratory on ice within 12 hrs of collection. Upon receipt, samples were stored at −20°C. Ileostomy donors were recruited through the Ostomy Association of Greater Lansing, and were most likely residents of Lansing, Michigan USA and its surrounding counties. Samples were stored at −80°C or −20°C for 3-4 years prior to use. Samples were randomly selected for testing from a bank of available samples. Samples were collected according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Michigan State University (Protocol 10-736SM).

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic organization of C. difficile MLST profiles. Maximum likelihood tree based upon concatenated Multi Locus Sequence Typing genes of the 399 current profiles available at https://pubmlst.org/cdifficile/ .35 Stars indicate position of strains used in this study with red stars indicating sequence types possessing either the treR L172I (ST1, ST41) or 4 gene insertion (ST11). Tree constructed using MEGA7.36

Extended Data Fig. 2. Growth of C. difficle strains.

a, The majority of strains can grow on 50 mM trehalose. Dashed grey line and band indicate mean growth in DMM without a carbon source and s.d. Solid lines indicate mean growth yield (OD600) for groups: Non-RT027/078 (n=10), RT027 (n=8), and RT078 (n=3). b, Deletion of treA ablates the ability of both CD630 (RT12) and R20291 (RT027) to grow on trehalose. This phenotype can be restored by supplying treA on an inducible plasmid (n=3 for each strain/group). c, RT244 strains (DL3110 and DL3111) possessing the treR L172I mutation are capable of growth on 10 mM trehalose (n=3 for each strain/group). d, CD1015ΔptsT can metabolize 50 mM trehalose (n=4 for each strain/group). For panels a-d points represent biologically independent samples, solid bars are mean.

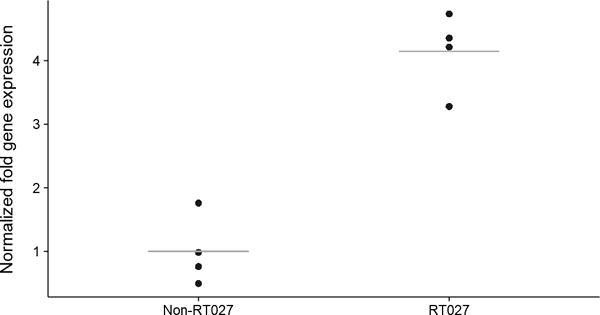

Extended Data Fig. 3. RT027 strains express treA at a significantly higher level than non-RT027 strains in the presence of 25 mM trehalose.

Each data point (n=4 Ribotypes per group) represents gene expression from a different, biologically independent, strain and is an average from 2-5 independent experiments. P=0.029, Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon Test (2 sided).

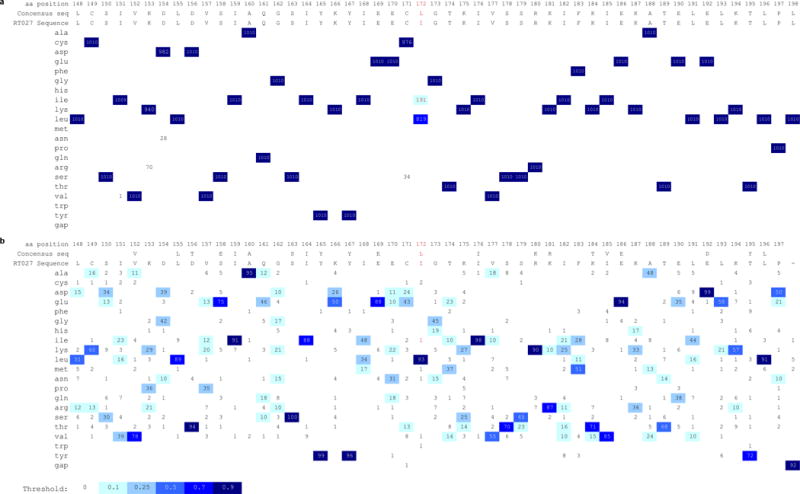

Extended Data Fig. 4. RT027 strains have a L172I mutation at a highly conserved site.

a, treR genes from available C. difficile WGS files on NCBI (accessed 11-May-2017) were identified by tblastn and translated to protein sequences. Sequence fragments < 240 amino acids were discarded and the remaining 1010 sequences aligned with Clustal Omega37. All 191 sequences containing the L172I SNP also contained the thyA gene, a marker for the RT027 lineage. ThyA was not found in any other genomes. Numbers indicate number of sequences with corresponding amino acid in that position. Multiple sequence alignment visualization generated with ProfileGrid.38 b, The TreR protein sequence from RT027 strain R20291 was blasted against non-C. difficile sequences in the NCBI database and the top 99 matches (along with R20291treR) aligned with Clustal Omega. The Leucine at position 172 was found to be conserved in 93 of 99 non-C. difficile sequences. To confirm the importance of this residue, TreR was blasted against all non-Clostridial sequences in the NCBI database and the top 500 hits saved. Following removal of duplicate species 191 sequences were aligned with Clustal Omega. The Leucine at residue 172 was conserved in 83% of sequences (not shown).

Extended Data Fig. 5. A treA knockout strain has decreased toxin production 48 hours after infection.

Mice were gavaged 104 spores of either R20291 or R20291ΔtreA and provided 5 mM trehalose in drinking water. Points represent toxin levels from individual mice (R20291 n=10, R20291ΔtreA n=11) euthanized 48 hours after infection. Bars are mean. Mice gavaged with R20291ΔtreA had significantly lower toxin levels (p=.0268 Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (2 sided), median 40960, IQR 23040-46080 Vs 92160, IQR 51200-102400).

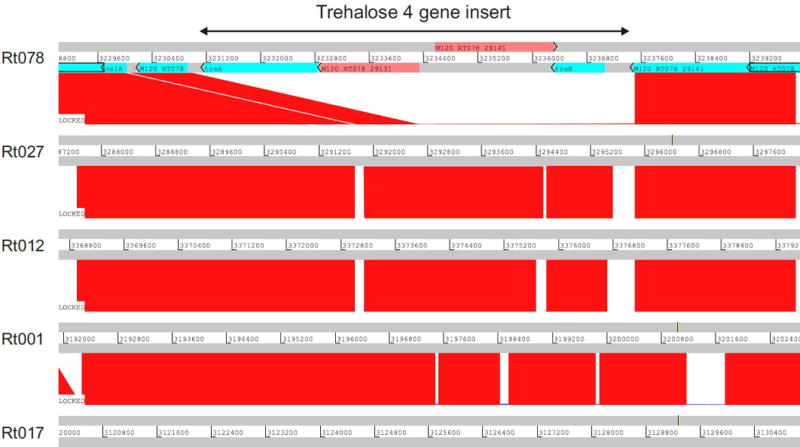

Extended Data Fig. 6. The 4 gene trehalose insertion is only present in the RT078 lineage.

Artemis comparison tool (ACT) displaying pairwise comparisons between C. difficile RT078 genome (M120) sequence and genome sequences from other C. difficile ribotypes (ribotypes indicated on the left). Numbers between grey bars indicate the genomic region where the trehalose four gene insert is located (3231169..3237057). Regions of sequence homology are displayed in red. The trehalose four gene insert of RT078 (indicated by the arrow on the top) was observed in RT078, but absent in other ribotypes.

Extended Data Table 1.

Compounds conferring ≥ 1.5-fold growth advantage in Biolog Phenotypic Microarray plates PM1 or PM2.

| Compound | CD630 | CD2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM1: | N-acetyl-D-glucosamine | + | + |

| L-proline | − | − | |

| D-trehalose | + | + | |

| D-mannose | + | + | |

| D-sorbitol | − | + | |

| D-mannitol | + | + | |

| D-fructose | − | + | |

| α-D-glucose | + | + | |

| α-Keto-Butyric acid | + | − | |

| L-serine | + | − | |

| L-threonine | − | − | |

| glycyl-L-proline | − | − | |

| PM2: | N-acetyl-neuraminic acid | + | + |

| D-arabitol | − | + | |

| arbutin | + | + | |

| D-melezilose | + | + | |

| salicin | + | + | |

| D-tagatose | + | + | |

| D-glucosamine | + | + | |

| β-hydroxy-butyric acid | + | + | |

| α-keto valeric acid | + | + | |

| hydroxy-L-proline | − | + | |

| L-leucine | + | + | |

| L-methionine | − | + |

Results of individual experiment where growth was (+) or was not (−) increased by at least 1.5-fold over DMM control.

Extended Data Table 2.

Spontaneous C. difficile mutants able to utilize 10 mM trehalose.

| Strain | Ribotype | Nonsense mutation* | Missense mutation | Insertions/deletions | Number of independent isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3014 | 001 | 18 | – | – | 1 |

| 2012 | 002 | 63 | – | – | 1 |

| 2012 | 002 | 89 | – | – | 2 |

| 2012 | 002 | 15 | – | – | 1 |

| 2012 | 002 | 22 | – | – | 1 |

| 2012 | 002 | – | S20I | – | 1 |

| 2012 | 002 | 64 | – | – | 1 |

| 2012 | 002 | 24 | – | – | 1 |

| 2012 | 002 | 20 | – | – | 1 |

| 1014 | 014 | – | S41I, T118K | 1 | 1 |

| 1014 | 014 | – | T118K | – | 1 |

| 2048 | 053 | 70 | – | – | 1 |

Numbers refer to the position in the consensus TreR amino acid sequence which become a premature stop codon.

Extended Data Table 3.

Strains, Primers, and Plasmids.

| Strains | Ribotype | MLST (Clade) | Note | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD630 | 12 | 54 (1) | Erythromycin sensitive | 31 |

| CD630ΔtreA | 12 | 54 (1) | This Study | |

| CD630 pRFP185-PaTc-ptsT | 12 | 54 (1) | This Study | |

| CD630ΔtreA pRFP185-PaTc-treA | 12 | 54 (1) | This Study | |

| R20291 | 27 | 1 (2) | 24 | |

| R20291ΔpyrE | 27 | 1 (2) | 24 | |

| R20291ΔtreA | 27 | 1 (2) | This Study | |

| R20291ΔtreA pRFP185-PaTC-treA | 27 | 1 (2) | This Study | |

| CD1015 | 78 | 11 (5) | † | |

| CD1015ΔpyrE | 78 | 11 (5) | This Study | |

| CD1015ΔptsT | 78 | 11 (5) | This Study | |

| CD1015ΔptsT pRFP185-PaTc-ptsT | 78 | 11 (5) | This Study | |

| VPI10463 | 3 | 12(1) | High toxin producer | |

| CD196 | 27 | 1 (2) | Ancestral RT027 strain | 32 |

| CD1007 | 053-163 | 63 (1) | † | |

| CD1014 | 014-20 | 2 (1) | 10 | |

| CD2012 | 2 | 8 (1) | † | |

| CD2018 | unique UM isolate | † | ||

| CD2046 | unique UM isolate | † | ||

| CD2048 | 053-163 | 63 (1) | 10 | |

| CD37 | 9 | 3 (1) | Non-toxigenic strain | 33 |

| CD4004 | 2 | 8 (1) | † | |

| CD4011 | 1 | 3 (1) | † | |

| CD2015 | 27 | 1 (2) | 10 | |

| CD3017 | 27 | 1 (2) | 10 | |

| CD4010 | 27 | 1 (2) | 10 | |

| CD4012 | 27 | 1 (2) | † | |

| CD4015 | 27 | 1 (2) | 10 | |

| CD2001 | 78 | 11 (5) | † | |

| CD2058 | 78 | 11 (5) | † | |

| DL3110 | 244 | 41 (2) | contains L172I in treR | 11 |

| DL3111 | 244 | 41 (2) | contains L172I in treR | 11 |

| Primers | Note | Sequence 5′ – 3′ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBS1.2 | Insertional deletion of treA in CD630 | atatcaagcttttgcaacccacgtcgatcgtgaatagaagattattgtgcgcccagatagggtg | |

| EBS1 | cagattgtacaaatgtggtgataacagataagtcattattattaacttacctttctttgt | ||

| EBS2 | cgcaagtttctaatttcggttttctatcgatagaggaaagtgtct | ||

| CR064 | CD630 treA insertion check | gcaacaatgatggtataggtgatataaatgg | |

| CR065 | ggaacagaaccatcaggtttagca | ||

| JCb092 | Upstream homology arm R20291 treA | 5′ phosphorylated | agacctttaaggagggataggggt |

| JCb093 | 5′ phosphorylated | aggagaaacgtacataggagtcaacca | |

| JCb094 | Downstream homology arm R20291 treA | 5′ phosphorylated | cctgaaacttatttgaataaattaaactacac |

| JCb095 | 5′ phosphorylated | gtttgatactgatggagggcctta | |

| JCb096 | gccctccatcagtatcaaacggggatcctctagagtcgac | ||

| JCb097 | Bridging oligos for ligase cycling | ctcctatgtacgtttctcctcctgaaacttatttgaataa | |

| JCb098 | cgaattcgagctcggtacccagacctttaaggagggatag | ||

| JCb135 | Upstream homology arm CD1015 pyrE | Sbfl | atacctgcaggagggacattttttattatcttcag |

| JCb136 | 5′ phosphorylated | acaacatcttcagcaattattatctttg | |

| JCb137 | Spacer from pMTL-YN2 | 5′ phosphorylated | gcggccgctgtatccatatgacc |

| JCb138 | 5′ phosphorylated | actagcgccattcgccattcagg | |

| JCb139 | Downstream homology arm CD1015 pyrE | 5′ phosphorylated | gcggccgctgtatccatatgacc |

| JCb140 | Ascl | atatggcgcgccataacattaataaaatttaaaatcaataattat | |

| JCb141 | Bridging oligos for ligase cycling | ataattgctgaagatgttgtgcggccgctgtatccatatg | |

| JCb142 | gaatggcgaatggcgctagttaataaaaacttaattattt | ||

| JCb153 | Upstream homology arm CD1015 ptsT | EcoRI | atagaattcaaaaacccaaaaatttaacc |

| JCb154 | BamHI | ataggatccatctacttatcctttctcttttttattataag | |

| JCb155 | Downstream homology arm CD1015 ptsT | BamHI | ataggatcccaaatgacaatatataaatataattcccttgg |

| JCb156 | Ncol | ataccatggcgtggttggtcatggttaca | |

| JCb167 | CD1015ΔptsT check | cggaatttcttttatattcatttgg | |

| JCb168 | cccaatttgttggagcactt | ||

| JCb225 | Conformation of pyrE knockout/repair | atgggaatgggcggaataac | |

| JCb226 | gcttggaagcagctacaacaga | ||

| JCb211 | CD1015 pyrE repair | Notl | atagcggccgcttacattcctaattccttgaactctc |

| JP048 | qPCR for C. difficile 16S DNA | ttgagcgatttacttcggtaaaga | |

| JP049 | ccatcctgtactggctcacct | ||

| CR045 | qPCR for C. difficile treA DNA | tacgctgatggtcctcgtat | |

| CR046 | cgcctcctttataatctgttttc |

| Plasmids | Reference |

|---|---|

| pMTL-YN2 | 24 |

| pMTL-YN2C | 24 |

| pMTL-YN4 | 24 |

| pRPF185 | 34 |

| Plasmid Maps | |

| pJC-R20291treAKO | https://benchling.com/s/seq-DANCiRRu7FwNqRJC09iu |

| pJC-CD1015pyrEKO | https://benchling.com/s/seq-Km3QbgAkU66DkNtaOA4R |

| pRFP185-PaTc-ptsT | https://benchling.com/s/seq-hKTbvE2pfE8MpvvEqFce |

| pJC-CD1015pyrERepair | https://benchling.com/s/seq-d25nmFmvSPtR1iQB8vka |

| pRFP185-PaTc-treA | https://benchling.com/s/seq-TTthHzlU2fsfRZ94oD9V |

Clinical isolates obtained from the Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH). Collected from Michigan hospitals between December 2007 and May 2008 References

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (U01AI124290-01 & 5U19AI09087202). The authors thank the members of the Ostomy Association of Greater Lansing for anonymously donating samples and Dr. Dena Lyras for the RT244 strains. We thank Vincent Young, David Mills, Jens Walter and Mauro Costa-Mattioli for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data for figures [1-5 and Extended Data 2, 3, and 5] are provided with the paper.

Author Contributions Concept and design of study RAB, JMA, JC, CR. Experiments: C. difficile growth, JC & CR; identification of L172I SNP and comparative analysis, CR & JC; treA RT-qPCR, HD; Mouse infection model, JC; Genetic manipulation of C. difficile strains, JC and CR; identification of RT078 trehalose insertion, CWK, HCL, TDL; Faecal minibioreactor competitions, JMA; Spontaneous C. difficile mutant identification, HD; Analysis by JC, CR, HD, JMA, and RB; manuscript drafted by JC, JMA, RAB; Critical manuscript revision by all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.He M, et al. Emergence and global spread of epidemic healthcare-associated Clostridium difficile. Nat Genet. 2012:1–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spigaglia P, et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Clostridium difficile isolates from a prospective study of C. difficile infections in Europe. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:784–789. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spigaglia P, Barbanti F, Dionisi AM, Mastrantonio P. Clostridium difficile isolates resistant to fluoroquinolones in Italy: Emergence of PCR ribotype 018. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2892–2896. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02482-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jhung MA, et al. Toxinotype V Clostridium difficile in humans and food animals. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1039–1045. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goorhuis A, et al. Emergence of Clostridium difficile infection due to a new hypervirulent strain, polymerase chain reaction ribotype 078. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1162–1170. doi: 10.1086/592257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna S, Gupta A. Community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: an increasing public health threat. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:63. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S46780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limbago BM, et al. Clostridium difficile strains from community-associated infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3004–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00964-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker AS, et al. Relationship between bacterial strain type, host biomarkers, and mortality in clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1589–1600. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He M, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of Clostridium difficile over short and long time scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7527–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914322107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson CD, Auchtung JM, Collins J, Britton RA. Epidemic Clostridium difficile strains demonstrate increased competitive fitness compared to nonepidemic isolates. Infect Immun. 2014;82:2815–2825. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01524-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim SK, et al. Emergence of a ribotype 244 strain of clostridium difficile associated with severe disease and related to the epidemic ribotype 027 strain. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1723–1730. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eyre DW, et al. Emergence and spread of predominantly community- onset Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 244 infection in Australia, 2010 to 2012. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.10.21059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polivkova S, Krutova M, Petrlova K, Benes J, Nyc O. Clostridium difficile ribotype 176 - A predictor for high mortality and risk of nosocomial spread? Anaerobe. 2016;40:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rupnik M, et al. Distribution of Clostridium difficile PCR ribotypes and high proportion of 027 and 176 in some hospitals in four South Eastern European countries. Anaerobe. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergoz R. Trehalose malabsorption causing intolerance to mushrooms. Report of a probable case. Gastroenterology. 1971:909–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergoz R, Bolte JP, Meyer zum Bueschenfelde Trehalose tolerance test. Its value as a test for malabsorption. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1973;8:657–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oku T, Nakamura S. Estimation of intestinal trehalase activity from a laxative threshold of trehalose and lactulose on healthy female subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:783–788. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higashiyama T. Novel functions and applications of trehalose. Pure Appl Chem. 2002;74:1263–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stabler RA, et al. Comparative genome and phenotypic analysis of Clostridium difficile 027 strains provides insight into the evolution of a hypervirulent bacterium. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R102. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-9-r102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1539–1548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1403772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theriot CM, et al. Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knetsch CW, et al. Genetic markers for Clostridium difficile lineages linked to hypervirulence. Microbiology. 2011;157:3113–3123. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.051953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouillaut L, Self WT, Sonenshein AL. Proline-dependent regulation of Clostridium difficile stickland metabolism. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:844–854. doi: 10.1128/JB.01492-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng YK, et al. Expanding the repertoire of gene tools for precise manipulation of the Clostridium difficile genome: allelic exchange using pyrE alleles. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fagan RP, Fairweather NF. Clostridium difficile has two parallel and essential Sec secretion systems. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:27483–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.263889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Kok S, et al. Rapid and Reliable DNA Assembly via Ligase Cycling Reaction. 2014 doi: 10.1021/sb4001992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfaffl MW. Relative quantification. Real-time PCR. 2006:63–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins J, Auchtung JM, Schaefer L, Eaton KA, Britton Ra. Humanized microbiota mice as a model of recurrent Clostridium difficile disease. Microbiome. 2015;3:35. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0097-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auchtung JM, Robinson CD, Farrell K, Britton RA. In: Clostridium difficile: Methods and Protocols. Roberts AP, Mullany P, editors. Springer; New York: 2016. pp. 235–258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dingle TC, Mulvey GL, Armstrong GD. Mutagenic analysis of the clostridium difficile flagellar proteins, flic and flid, and their contribution to virulence in hamsters. Infect Immun. 2011;79:4061–4067. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05305-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popoff MR, Rubin EJ, Gill DM, Boquet P. Actin-specific ADP-ribosyltransferase produced by a Clostridium difficile strain. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2299–2306. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2299-2306.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith CJ, Markowitz SM, Macrina FL. Transferable tetracycline resistance in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19:997–1003. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.6.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fagan RP, Fairweather NF. Clostridium difficile has two parallel and essential Sec secretion systems. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:27483–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.263889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffiths D, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:770–778. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01796-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sievers F, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roca AI, Abajian AC, Vigerust DJ. ProfileGrids solve the large alignment visualization problem: influenza hemagglutinin example. F1000Research. 2013 doi: 10.3410/f1000research.2-2.v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]