Abstract

Stroke continues to be a public health problem and risk perceptions are key to understanding people’s thoughts about stroke risk and their preventative health behaviors. This review identifies how the perceived risk of stroke has been measured and outcomes in terms of levels, predictors, accuracy, and intervention results. Sixteen studies were included. The perceived risk of stroke has primarily been assessed with single-item measures; no multi-item surveys were found. In general, people tend to perceive a low-moderate risk of stroke; the most common predictors of higher stroke risk perceptions were having risk factors for stroke (hypertension, diabetes) and a higher number of risk factors. However, inaccuracies were common; at least half of respondents underestimated/overestimated their risk. Few studies have examined whether interventions can improve the perceived risk of stroke. Strategies to improve stroke risk perceptions should be explored to determine if accuracy can promote healthy lifestyles to reduce stroke risk.

Keywords: Risk Perception, Stroke, Measurement, Behavior Change

Stroke, one of the leading causes of death and disability in the world, remains a largely preventable disease. Maintaining ideal cardiovascular health by living a healthy lifestyle and managing vascular risk factors can prevent most strokes (Kulshreshtha et al., 2013; Mozaffarian et al., 2016). However, there continues to be a lack of awareness about personal stroke risk that may hinder risk reduction behaviors. Researchers have called for the development of theory-based interventions for the reduction of stroke through behavior change (Boden-Albala & Quarles, 2013). Risk perception is a central focus of many health behavior theories including the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, 1974), Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers, 1975), Extended Parallel Process Model (Witte, 1992), and the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). In general, these theories propose that higher risk perception is associated with the initiation of preventative health behaviors. Risk perception has been conceptually defined as an individual’s belief about his or her chances of becoming ill (Hay et al., 2007), people’s perceptions about their susceptibility to various ailments and diseases (Rimal, 2001) and the likelihood and severity of losses or negative outcomes (van der Plight, 1996). How individuals perceive their stroke risk may influence their decision to engage in risk reduction behaviors to prevent a stroke or decisions to seek medical attention if they experience symptoms of a stroke.

Risk perception is often assessed to better understand people’s thoughts about disease and their preventative health behaviors. However, risk perception is a highly complex concept and the relationship between risk perception and behavior change can be inconsistent. Several factors may influence one’s perception of risk and response to that risk including individual characteristics, perceptions of general health, knowledge of the illness or disease, risk factor status, family history of disease, perceived control, personal experience, and media exposure (Fiandt, Pullen, & Walker, 1999; Slovic, 2000). Individual risk perceptions may vary based on current behaviors and behavioral intentions. Hay et al. (2007) argued that a bidirectional relationship exists between risk perception and behavior change over time, such that, individuals who engage in risky behaviors may perceive a higher risk and risk perception may influence individuals to make behavior changes, but once the protective behavior is adopted, perception of risk is likely to decrease. Therefore, ongoing evaluations of perceived risk and positive reinforcement are needed. Underestimations of perceived risk can hinder the decision-making process to act in response to the risk. Optimistic bias is a concept synthesized by Weinstein (1980) to explain this underestimation, the belief that one is less at risk of experiencing a negative health event than others. Lastly, poor study designs, inaccurate measurements, and conceptual problems also may explain the inconsistent or unexpected findings between risk perception and behavior change (Brewer, Weinstein, Cuite, & Herrington, 2004; van der Plight, 1996). Understanding the role of risk perception in behavior change and how the perceived risk of stroke has been used can help nurse researchers and clinicians more effectively develop, implement and evaluate strategies to prevent stroke. There are reviews on risk perception for cardiovascular disease (Imes & Lewis, 2014; Hammond, Salamonson, Davidson, Everett, & Andrew, 2007; Webster & Heely, 2010), but none were found on the perceived risk of stroke. Although stroke shares many of the same risk factors that contribute to heart disease, risk perceptions can vary by disease.

Purpose

To explore the perceived risk of stroke, we conducted a review of the literature to identify articles that described the measurement and outcomes of the perceived risk of stroke. Outcomes was defined as levels of perceived stroke risk, predictors of perceived stroke risk, accuracy of perceived stroke risk and results of interventions to improve perceived stroke risk.

Methods

A search of four databases CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsychInfo and PubMed was conducted for articles published between August 1, 1996 and August 1, 2016. The dates were selected to span a 20-year period that included a seminal paper on cardiovascular risk perception by Samsa et al. in 1997. The primary keywords used were “stroke” and “risk perception or perceived risk”. Additional keywords, similar to risk perception (i.e. perceived susceptibility, perceived vulnerability), were also used with the word “stroke” in secondary searches.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: 1) were published between August 1, 1996 and August 1, 2016 in peer reviewed journals; 2) written in the English language; 3) used a quantitative design; 4) focused on primary prevention of stroke (i.e. < 20% of the sample had a history of stroke); 5) described the measurement of perceived personal risk of stroke, and 6) described the levels of perceived risk of stroke. Studies with qualitative designs, dissertations, and articles that measured perceived risk of stroke under the umbrella of cardiovascular disease or in conjunction with heart disease or heart attack were excluded.

The majority of studies assessing the perceived risk of stroke were non-experimental and descriptive, therefore study selection and review were guided by Grimes and Schulz (2002). Article selection and data extraction were undertaken by the first and third authors and conflicts were resolved through discussions by all authors. A template was used to extract the data.

Results

Included Studies

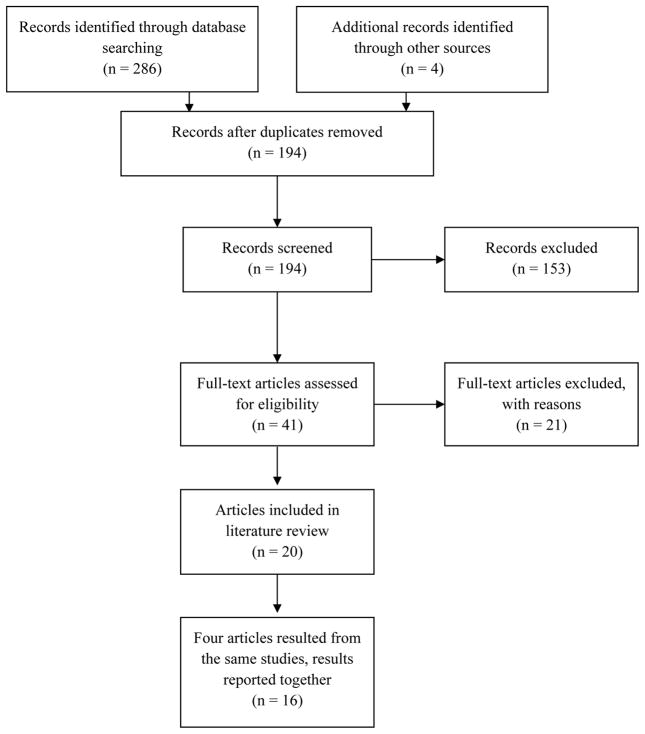

The primary search resulted in 290 articles. A flowchart illustrating article selection is in Figure 1. Following a removal of duplicates and articles based on titles and abstracts 41 were retrieved for further assessment. Upon further assessment 21 articles were excluded for the following reasons: ≥ 20% of the sample had a history of stroke (n= 4), perceived risk of stroke was not measured (n = 14) or was measured within cardiovascular disease (n = 2), and levels of perceived stroke risk (n = 1) not reported. No additional articles resulted from the secondary searches using perceived susceptibility and perceived vulnerability. Twenty articles were included in the review however four articles resulted from the same studies. Results from these articles are reported together for a total of 16 studies. Findings from the studies using the data extraction template are detailed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

The Perceived Risk of Stroke Article Selection Flowchart

Table 2.

Summary of Studies Describing the Measurement and Outcomes of Percevied Risk of Stroke

| Yr. & Author | Sample | Measurement of Perceived Stroke Risk | Levels of Perceived Stroke Risk | Predictors, Accuracy & Intervention Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Shafaee et al., 2006 |

N= 400 Country: Oman Female: 47.5% Age: M=57±9.5 |

Questionnaire administered in a face-to-face session | 7.2% yes 62.0% no 30.8% do not know |

Not applicable |

|

Asimakopoulou, Skinner, et al., 2008 a Asimakopoulou, Fox, et al., 2008 |

N= 95 Country: United Kingdom 85% White Age: M=64±8.67 |

In-person visual analogue scale | M= 33 out of 100 | Accuracy: actual risk was < 10 based on the UK Prospective Diabetes Study Risk Engine, participants tended to overestimate their risk. |

|

Aycock & Clark 2016 a Aycock et al., 2014 |

N= 66 Country: US Female: 71% Black: 100% Age: M=43±9.4 |

In-person administration of questionnaires | 11% high 23% moderate 42% little risk 24% no risk |

Predictors: *No differences in perceived stroke risk were found by family history of stroke. |

| Accuracy: 47% had an accurate perception of their stroke risk, 44% underestimated and 9% overestimated. | ||||

| Dearborn & McCullough, 2009 |

N= 212 Country: US Middle-aged women with at least 1 risk factor White: 91.5% Black: 5.6% Age: M=63.0±7.2 |

Mailed visual analogue scale | M= 5.7± 2.3 for personal risk and, 5.5±1.7 for other womens’ risk out of 10 | Predictors: Other women’s risk of stroke; worry about stroke; having hypertension or diabetes. |

| Accuracy: Women perceived their risk as similar to their peers. Compared to women with actual low risk, women at high risk of stroke perceive their risk to be no different than those of other women. | ||||

| Fiandt et al., 1999 |

N= 102 Country: US 100% White Age: M=74±5.99 |

Telephone interview | 10.8% high 42.2% medium 42.2% low |

Predictors: history of hypertension, general perception of poor health |

| Accuracy: 48% had an accurate perception of their stroke risk, 28% overestimated, and 24% underestimated. | ||||

| Fournaise et al., 2015 |

N= 178 Country: US Age: M=70.6±8.31 Patients with atrial fibrillation Female 55% |

Face to face interviews using a standardized template | 62% of patients scored on the lower end (1–3 points) of the scale. | Accuracy: No significant association between clinical stroke risk and patient’s stroke risk perception. 60% had an unrealistic perception of their stroke risk. No significant increase in risk perception was observed for those with a lower compared to a higher risk factor load. |

| Frijling et al., 2004 |

N= 1,557 Country: Netherlands Female: 57.8% Age: M=62.5±14.4 |

Mailed visual analogue scale | M= 29.8% out of 100 | Predictors: Older age, smoking, familial history of CVD, self-rated fair/poor health, lower sense of internal locus of control, and higher sense for physician locus of control |

| Accuracy: Mean absolute difference between perceived and actual 10-yr. risk was 24.6%. Patients tended to over-estimate their risk | ||||

| Harwell et al., 2005 |

N= 800 Country: US Female: 60% White: 96% Am. Indian: 2% Age: 61±12.1 |

Computer-assisted telephone survey | 39% yes 56% no 5% unsure |

Predictors: Age (45–64); having ≥ 2 risk factors, history of diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease, and stroke/TIA. |

| Only 14% reported ever receiving information about being at risk for stroke from their physician. | Accuracy: Perceived risk increased as the number of reported risk factors for stroke increased, however, almost half of respondents with ≥ 3 risk factors did not consider themselves to be at risk. | |||

| Kraywinkel et al., 2007 |

N= 1483 Country: Germany Male: 56.8% Female: 43.2% Age: M=47 |

Mailed questionnaire | 13% high risk 52% moderate risk 32% low or non-existent risk |

Predictors: Subjective perception of poor general health; moderate overweight/obesity; diabetes, heart disease. |

| Intervention: 27% of those who were informed about increased stroke risk at baseline perceived a high stroke risk during the follow-up survey at 3–12 months. | ||||

|

Marx et al., 2008 a Marx et al., 2010 |

N=1,008 Country: Germany Female: 56% Age: male= M=53.2±14.4 female= M=53.0±14.9 |

Computer automated telephone interviews were conducted three months prior to and after the multimedia campaign | 32.7% yes | Predictors: *More men than women considered themselves at risk 36.9% vs. 30.9%. Risk increased with every additional stroke risk factor. Lower education associated with increased risk. |

| Intervention: Awareness of perceived stroke risk increased from 32.7% – 41.9%. | ||||

| Ntaios et al., 2015 |

N= 723 Country: Greece Female: 58% Age: M=47.4±17.8 |

Telephone survey using an online structured questionnaire | 11% high risk 43% small risk 25% no risk 21% do not know |

Accuracy: most respondents with a known risk factor considered themselves as having no/little risk of stroke. |

| Powers et al., 2011 |

N=89 Country: US Male 98% White 51% Black 45% Age: M= 67±8 |

Face to face interviews | M= 42±31 out of 100 | Intervention: Perceived stroke risk declined in both arms but there were no significant within/between group differences. |

| Powers et al., 2008 |

N=296 Country: US male veterans with HTN White: 59.8% Black: 37.4% Other:2.8% Age: M=63.9±10.9 |

In-person single-item survey | Median score was 5 out of 10 scale. | Accuracy: Among those with a low Framingham Stroke Risk Score, 71% had an accurate risk perception, 29% overestimated. Among those with high Framingham Stroke Risk Score, 22.1% had an accurate risk perception, 77.9% underestimated their stroke risk. |

| Vaeth & Willett, 2011 |

N=656 Country: US Female: 53.3% |

Face to face interview | 18.4% above average 40.7% average 29.9% below average |

Predictors: Risk of stroke was marginally associated with blood pressure measurement. Both above- and below-average perceived risks of stroke were associated with a decreased likelihood of blood pressure self-monitoring. |

| Wang et al., 2009 a Wang et al., 2012 |

N= 2362 Country: US Female: 70.9% Hispanic: 3% White: 91% Black: 4% Asian: 3% Age: M=50.3 |

Online survey | Total M= 2.63±.91 Male M=2.58±.88 Female M=2.68±.93 |

Predictors: Perceived risk for stroke greater among women, and lower than perceived risk of cancer, heart disease and diabetes. |

| Intervention: *A greater percentage of underestimators receiving the Family Healthware intervention increased their perceptions of stroke risk than control participants (11% vs. 8%). | ||||

| Yang et al., 2013 |

N= 941 Country: China Female: 61.8% Age: M=58.6±15.2 |

Face to face interview | 17.7% yes 49.8% no 32.8% unsure |

Predictors: Age 45–64 more likely to perceive risk of stroke; health insurance; history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart disease, stroke and increase in the number of risk factors. |

| Accuracy: Only 41% of respondents with 3 or more risk factors responded yes to being at risk. |

denotes second of two articles resulting from one study

CVD = Cardiovascular Disease; TIA = Transient Ischemic Attack; HTN = Hypertension

Studies reviewed were published between 1999 and August of 2016. Nine studies were conducted in the United States, two in Germany and one each in China, Greece, Netherlands, Oman, and the United Kingdom. Sample sizes ranged from 66 to 2,362 participants. The samples included men and women in all studies except three, one targeted only men and two targeted women. The majority of studies were either correlational (n =7) or descriptive (n =5) and four studies were experimental, two randomized controlled trials and two, one-group pre-post test designs. Nine studies did not include individuals with a history of stroke and seven had a sample consisting of 6 to 18% of stroke survivors. There were ten studies that targeted individuals at risk of stroke; the target population had a diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes or atrial fibrillation, they had at least one risk factor for stroke, or identified as >45 years.

Measurement of Perceived Stroke Risk

Different modes (i.e. survey, phone interview) were used to collect data on the perceived risk of stroke, but all studies used a single item measure (Table 1). Most researchers (n= 13) used the word “risk” within their queries, while others used “chances” or “likelihood”. Specific timepoints to the occurrence of stroke were used in five studies, and included over the next year, 10 years, 10–20 years, 20 years, and lifetime (i.e. absolute risk). Some researchers asked participants to estimate their risk of stroke based on their health status/disease (n= 2) or in comparison to other people their age and/or sex (n=3; i.e. comparative risk).

Table 1.

Queries and Responses for the Perceived Risk of Stroke

| Queries | Responses | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| “Do you think you are at increased risk for stroke?” | yes, no or do not know | Al Shafaee et al., 2006 |

| “Over the next year, what do you think is your risk of developing a stroke as a result of your diabetes?” | 0–100; 0=no and 100=certain to happen | Asimakopoulou et al., 2008 |

| “What is your risk/chances of having a stroke in the next 10 to 20 years?” | no, low, moderate, high risk | Aycock & Clark, 2016 |

| Asked to rate perceived personal risk of stroke and that of other women. | 1–10; 1=low and 10=high | Dearborn & McCullough, 2009 |

| “Compared to other women your age, how would you rate your risk of having a stroke in the next 10 years?” | low, medium and high | Fiandt et al., 1999 |

| “What is your perceived personal risk for developing a blot clot in the brain within the next 10 years?” and “developing a bleeding in the brain within the next 10 years?” | 1–7; 1=highly unlikely and 7=highly likely | Fournaise et al., 2015 |

| Asked to estimate 10-yr risk of stroke. | 0–100; 0=no and 100=high | Frijling et al., 2004 |

| “Do you believe you are at increased risk of having a stroke?” | yes or no | Harwell et al., 2005 |

| Asked to rate lifetime risk of suffering a stroke. | nonexistent, low, moderate, or high risk | Kraywinkel et al., 2007 |

| “Do you consider yourself to be at risk of stroke?” | yes or no | Marx et al., 2008 |

| Asked to estimate stroke risk perception. | no, small, high, do not know | Ntaios et al., 2015 |

| “How would you rate your likelihood of having a stroke as a result of high BP?” | 1–10; 1=not going to have a stroke 10=will definitely have a stroke | Powers et al., 2008 |

| Asked to estimate 10-yr risk of stroke. | 1–100 scale; 1=low and 100= high | Powers et al., 2011 |

| “How likely do you think you are to have each of the following health conditions (stroke) in your lifetime?” | 1–5; 1=low or below average, 3=average, 5=high or above average | Vaeth & Willett, 2011 |

| “Compared to most people your age and sex, what would you say your chances are for developing a stroke?” | 1–5; 1=much lower than average and 5=much higher than average | Wang et al., 2009 |

| “Based on your current physical status, do you think you are at risk of having a stroke?” | yes, no, or unsure | Yang et al., 2013 |

The most commonly used query responses were yes or no (Al Shafaee, Ganguly, & Asmi, 2006; Harwell et al., 2005; Marx, Nedelmann, Haertle, Dieterich, & Eicke, 2008; Yang et al., 2013), ordinal word choices (Aycock & Clark, 2016; Fiandt et al., 1999; Kraywinkel, Heidrich, Heuschmann, Wagner, & Berger, 2007; Ntaios et al., 2015), and Likert-type scales (Fournaise, Skov, Bladbjerg, & Leppin, 2015; Powers, Oddone, Grubber, Olsen, & Bosworth, 2008; Vaeth & Willett, 2011; Wang et al., 2009). A visual analogue scale (0/1–100; Asimakopoulou, Skinner, Spimpolo, Marsh, & Fox, 2008; Frijling et al., 2004; Powers et al., 2011) and number scale (1–10; Dearborn & McCullough, 2009) also were used. In four studies (Al Shafaee et al., 2006; Harwell et al., 2005; Ntaios et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2013) a response of unsure/do not know was included as a choice.

Levels of Perceived Stroke Risk

Levels of perceived stroke risk were reported using descriptive statistics. Based on the yes or no responses, the percentage of individuals who responded yes to being at risk of stroke ranged from 7.2–39%. For the ordinal word choices, the percentage of participants indicating they were at risk of stroke, either moderate or high risk, ranged from 11–65%. For the scales, respondents tended to select the low to mid-point, indicating a low to moderate perceived risk of stroke. When unsure/do not know was included in the rating, it was selected by 5–32.8% of participants. Studies that focused on populations with known risk factors appeared to have similar estimates of perceived stroke risk compared to general community based studies.

Predictors of Perceived Stroke Risk

Seven studies perfomed analyses to identify factors associated with levels of perceived stroke risk. The most commonly identifed predictor of a higher perceived stroke risk was having known/established risk factors for stroke: hypertension (Fiandt et al., 1999; Harwell et al., 2005; Marx et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2013) diabetes (Harwell et al., 2005; Kraywinkel et al., 2007) heart disease (Harwell et al., 2005; Kraywinkel et al., 2007; Marx et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2013), high cholesterol (Harwell et al. 2005; Yang et al., 2013) and prior stroke (Harwell et al. 2005; Yang et al., 2013). A higher number of risk factors (Harwell et al. 2005; Marx et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2013), perception of poor general health (Fiandt et al., 1999; Frijling et al, 2004; Kraywinkel et al., 2007), age 45–64 years (Frijling et al., 2004; Harwell et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2013), and worry about stroke (Kraywinkel et al., 2007) or high blood pressure in relation to stroke (Powers et al., 2008) also were identified. However, in two studies diabetes (Fiandt et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2013) and age (Fiandt et al., 1999; Kraywinkel et al., 2007) were not found to independently predict higher perceived stroke risk. Level of education (Harwell et al. 2005; Kraywinkel et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2013) atrial fibrillation (Fiandt et al., 1999; Harwell et al., 2005) and cigarette smoking (Fiandt et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2013) also were less likely to predict a higher perceived stroke risk. Studies examining gender differences had varying findings; one study indicated women perceived a higher stroke risk (Wang et al., 2009) another found men perceived a higher stroke risk (Marx et al., 2010), while no gender differences were found in three studies (Frijling et al., 2004; Harwell et al. 2005; Yang et al., 2013). Only two studies examined the influence of family history of cardiovacular disease or stroke on the perceived risk of stroke and the findings differed (Aycock et al., 2015; Fiandt et al., 1999). Only one study examined racial/ethnic differences finding no difference (Yang et al., 2013) in perceived stroke risk.

Accuracy of Perceived Stroke Risk

Accuracy of perceived stroke risk was assessed in 10 studies. Researchers compared the participants’ perceptions of their perceived stroke risk with a measure of their actual stroke risk. In four studies, actual risk was based on the participant’s number of personal risk factors for stroke. Two studies used the Framingham Stroke Risk Score and the remaining studies used either the National Stroke Association’s Stroke Risk Scorecard, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey, the CHA2DS2-VASc algorithm or the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Risk Engine. There were no significant associations between perceived and actual stroke risk in any studies. On average about half of the respondents in the studies had inaccurate stroke risk perceptions. The inaccuracies tended to be underestimations of stroke risk (Aycock & Clark, 2016; Dearborn & McCullough, 2009; Fournaise et al., 2015; Harwell et al. 2005; Ntaios et al., 2015; Powers et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013), however, in three studies (Asimakopoulou et al., 2008; Fiandt et al., 1999; Frijling et al., 2004) with samples having known stroke risk factors (e.g. diabetes) more participants overestimated than underestimated their risk.

Interventions to Improve Accuracy of Perceived Stroke Risk

Interventions to improve accuracy of perceived stroke risk were found in four studies. Powers et al. (2011) evaluated the impact of personalized coronary heart disease and stroke risk communication on knowledge, beliefs and behavioral intentions among veterans with a diagnosis of hypertention. They found that perceived stroke risk declined over three months in both the personalized risk communication group and the standard risk factor education group, but no significant within or between group differences were observed. No between group differences in patient behaviors (i.e. medication adherence, exercise, smoking cessation) were observed. Accuracy of perceived stroke risk was not fully described. Researchers concluded that the small sample size may not have been adequate to detect differences and that personal risk communication needs to be frequent and intensive to impact health behaviors. They noted that participants receiving the intervention reported significantly less decisional conflict over their preferred risk reduction method than the comparison group.

Kraywinkel et al. (2007) provided individualized written feedback to participants about their stroke risk factors and used traffic light symbols to communicate risk levels, “green” if normal, “yellow” if elevated two to four-fold and “red” if elevated more than four fold based on the Framingham Stroke Risk Scale. Three to 12 months following the feedback, only 27% of those who were informed about increased stroke risk perceived a high stroke risk. Researchers concluded that since partcipants were also provided with strategies to modify their risk, behavior changes and newly started medications may have contributed to a more optimistic self perception of risks over time. In contrast, Marx et al. (2008) found a statistically signficant increase in awareness of being at risk for stroke following a multimedia campaign to improve public stroke knowledge. The three month intervention included mass media, poster and flyer advertisements on stroke risk factors and warning signs. Awareness of perceived stroke risk increased significantly from 32.7% at baseline to 41.9% (p <.01) following the intervention. Wang et al. (2012) also observed an increase in perceptions of stroke risk among participants receiving the Family Healthware Program. Among participants who underestimated their familial risk of stroke at baseline, a higher percentage of participants receiving familial disease risk information and personalized prevention messages increased their risk perception for stroke compared to controls (11% vs 8%; p<.05). Although risk perception changed, behavior changes or intentions to change behaviors to reduce risk were not evaluated.

Discussion

The perceived risk of stroke is a concept that has been examined internationally, with most studies conducted in the United States. Greater exploration of perceived stroke risk is needed, especially in low to middle income countries where stroke rates are the highest (Feigin et al., 2014) and among minorities disproportionately affected by stroke. Only four studies had adequate samples of African Americans/Blacks, one study focused on Asians and no studies explored the perceptions of stroke risk among Hispanics/Latinos. Women are at higher risk of stroke than men and the studies reviewed had adequate samples of women; however, among the studies where gender differences were examined (Frijling et al., 2004; Harwell et al., 2005; Kraywinkel et al., 2007; Marx et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013) findings were inconsistent. Although older age is associated with increased stroke risk, the best time to reduce cardiovascular and stroke risk is in early adulthood (Hayman, Helden, Chyun, & Braun, 2011; McGill, McMahan, & Gidding, 2008) yet, few studies (Aycock & Clark, 2016) have targeted young adults to assess their perceived stroke risk. More research about perceived stroke risk is needed with younger adults and to examine gender differences.

In all the studies, a single item was used to measure the perceived risk of stroke. Although single-item measures are less time-consuming, minimize response burden, and can be administered in a variety of ways, a single item may not effectively portray how people think and feel about their risk of stroke. We did not identify any multi-item measures of the perceived risk of stroke. Sullivan, White, Young, & Scott (2010) developed the Cerebrovascular Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (CABS-R), however, it uses perceived susceptibility as one of three subscales on health beliefs related to diet and exercise behaviors for stroke prevention. Multi-item scales of risk of heart disease and HIV (Ammouri & Neuberger, 2008; Chan, 2014; Napper, Fisher, & Reynolds, 2012) examine multiple dimensions of risk perception, are not behavior specific, and have undergone preliminary psychometric analyses. Napper et al. (2012) suggested that more comprehensive measures of risk perception that address cognition and emotion may be more effective for assessing the accuracy of risk perceptions and whether risk perception predicts future behavior.

Other inconsistencies were noted in this review such as the use of alternate wording to assess risk, for example “chances” or “likelihood”. Whether individuals understand the meaning of risk is unclear. Defining risk, providing alternate word choices, and relating risk of stroke to other personal risk may provide clarification if needed. With the single-item measures, there were no detailed descriptions of reliability and validity testing. Rather, researchers (Asimakopoulou et al., 2008; Aycock & Clark, 2016; Fiandt et al., 1999; Kraywinkel et al., 2007; Ntaios et al., 2015; Powers et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013) cited that the type of measure used was well established in the literature or had been used in previous studies, however most of the single items had been adapted or had not been previously validated among the groups under study. The single-item queries varied, which makes it difficult to establish measurement validity and compare findings across studies.

Researchers have described effective strategies to communicate cardiovascular risk information (Waldron, van der Weijden, Ludt, Gallacher, & Elwyn, 2011) including scripts for assessing preferred communication methods (Christian, Mochari, & Mosca, 2005) and the best formats for conveying health risk (Lipkus, 2007) but to our knowledge this is the first review to examine measurement strategies for assessing perceived stroke risk. Studies examining the psychometric properties of existing measures and individual preference for estimating risk are needed.

The response options for the perceived stroke risk queries also varied, further complicating the comparison of findings across studies. Some researchers acknowledged measurement as a limitation of their studies (Asimakopoulou et al., 2008; Fournaise et al., 2015; Frijling et al., 2004; Powers et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013). Frijling et al. (2004) found that one-fourth of the patients did not provide estimates of stroke risk and suggested these patients did not understand the visual analogue scale. Fournaise et al. (2015) noted patients’ difficulty with interpreting numerical scale points and problems with scales not including a “don’t’ know” option. Lastly, Yang et al. (2013) used yes/no responses and commented that this does not reflect the survey results and may have bias because participants were unable to express their level of risk.

Problems with measuring risk perceptions are not uncommon. Other researchers have discussed the inaccuracies of visual analogue scales and challenges individuals face with using numerical scales (Baghal, 2011; Waldron et al., 2011). Boden-Albala, Carman, Moran, Doyle, and Paik (2011) has examined perceived risk of stroke among stroke survivors and suggested that the manner in which responses are presented may alter the risk estimate, such that; when responses were presented in a qualitative manner, respondents tended to underestimate their risk and when presented in a quantitative manner they tended to overestimate their risk. This observation was also reflected in our review. Ferrer and Klein (2015) also discuss the influence of measurement choices, absolute risk versus comparative risk, on accuracy of risk perceptions.

Strategies for improving the accuracy of estimates when measuring risk perceptions also have been discussed. Asimakopoulou et al. (2008) recommended using not one but multiple formats to help people understand and better estimate their risk (e.g. a visual analogue scale with numeric and word labels), while Frijling et al. (2004) suggested using “pictorial representations of risk, comparisons of everyday risk (e.g. road crashes) or integers (a chance of 1 in 10).” In the risk perception literature on smoking, vague quantifier scales or qualitative response options (e.g. not at all, little, somewhat, and very risky) were easier for respondents to use and were better predictors of smoking behaviors than numeric scales (Baghal, 2011; Slovic, 1998). Using a measure that combines wording to facilitate respondents understanding of risk and numbers to allow for comparisons of perceived versus actual risk may provide more accurate and valid representations of risk.

In deciding on response options, researchers also must consider whether to include “don’t know” or “unsure” as a choice. Few studies included these as response options but for those that did (Al Shafaee et al., 2006; Harwell et al., 2005; Ntaios et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2013) up to 1/3 of participants selected the option. “Don’t know” responses are typically used so that respondents do not feel forced to answer a question and to limit guessing to avoid inaccuracies (Checkmarket.com, 2016). However, Beatty, Hermann, Puskar, and Kerwin (1998) suggests that a “don’t know” response may be selected to avoid having to think about the answer or it could mean “I don’t want to know”, as a way of denying reality. Whether respondents “don’t know” or provide an inaccurate estimate of their stroke risk, stroke education is needed to increase stroke awareness and correct discrepancies in perceived stroke risk.

Having established risk factors for stroke and a higher number of these risk factors were the most common predictors of higher perceived stroke risk. This is not surprising, as risk factors typically help to shape people’s perceptions of risk. However, researchers reported that not all individuals with known risk factors for stroke or multiple risk factors for stroke considered themselves to be at higher risk (See Table 2; Harwell et al., 2005; Ntaios et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2013).

Some explanations for these discrepancies include a lack of awareness or insufficient knowledge about the seriousness of stroke risk factors. Furthermore, when individuals are provided with information about their risk, they may not understand the information provided or forget what they were told (Fournaise et al., 2015). Another explanation is that individuals who are being treated for their co-morbidities or have risk factors that are under control or those who are engaging or planning to engage in healthy behaviors may perceive a lower risk or no risk of stroke (Frijling et al., 2004; Kraywinkel et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013). For example, Fournaise et al. (2015) argued that high risk patients with atrial fibrillation who underestimated their risk of stroke, may believe that having less and/or non-major additional risk factors and receiving adequate anticoagulant treatment lowered their risk. Brewer et al. (2004) suggested questions assessing perceived risk need to specify a behavioral context for individuals to factor in treatments or anticipated changes in behavior to their risk estimates. For example, “If you don’t change any stroke related health behaviors, what is your risk of having a stroke in the next 10 years?” Lastly, individuals may not want to claim their stroke risk out of fear of stigma (Yang et al., 2013) or fear that the event will actually occur (Aycock & Clark, 2016). These findings underscore the need for ongoing public education on the risk factors for stroke, health screenings to identify or monitor stroke risk, and effective stroke risk communication strategies.

In general individuals perceived a low to moderate risk of stroke. We believe that whether individuals’ perceptions of stroke risk were accurate is more important. Overall people tend to have inaccurate perceptions of their risk of stroke, either underestimations (optimistic bias) or overestimations (pessimistic bias). While theories propose that individuals who underestimate their risk are less likely to comply with prevention behaviors, researchers have found that overestimating one’s risk can be as harmful. Individuals who overestimate their risk may experience fear and anxiety over the threat of illness/disease and may result in people ignoring risk information (Brown, 2001) and being less motivated to engage in healthy self-care behaviors (Asimakopoulou et al., 2008). Individuals who worry about stroke or have a fatalistic belief about stroke tend to overestimate their risk (Boden-Albala et al. 2011). When patients are given accurate risk information, their mood (Asimakopoulou et al., 2008) and anxiety (Koelewijnvan Loon et al., 2010) can improve. However, Powers et al. (2008) suggests that in high-risk patients, anxiety may be an unavoidable component of promoting accurate risk perceptions. Strategies should be in place to help these individuals best manage their risk factors and the emotions related to their disease risk.

Findings from the four intervention studies suggest that an individual’s perceived risk of stroke can be changed and discussions about risk can facilitate decision making for risk reduction. For risk communication and risk management to be successful there should be a two-way process (Slovic, 2000). Nurse clinicians and researchers should start with assessing perceived stroke risk to better understand peoples’ thoughts and knowledge about stroke risk and communicate the accuracy of their risk perception. Individuals’ inaccuracies of stroke risk may result from the measurements used, as well as the ongoing lack of awareness of stroke and significance of stroke risk factors. Regardless, it is important to resolve differences between perceived and actual stroke risk by continuing to educate the public about stroke.

To our knowledge this is the first critical review of the literature evaluating risk perceptions for primary stroke prevention, which is a strength. Selection bias is possible because non-English-language studies and unpublished studies were excluded. Sample sizes in some studies were small. The quality of studies varied and not all information of interest was available in the study reports. Measurement limitations were a focus of the review and were discussed throughout the paper.

In Samsa et al.’s (1997) seminal paper examining perceived stroke risk among patients at increased risk, patients who were counseled by a physician about their risk for cardiovascular disease had a more accurate perception of their risk than those who did not receive counseling. Recommendations for how healthcare providers should employ risk perception includes assessing risk on a regular basis, measuring risk with consideration of the limitations addressed in this paper, asking the basis for the perception, discussing perceived versus actual risk and determining whether patients are interested and feel capable of modifying or managing their actual risk, and providing patients with resources and support to facilitate risk reduction behaviors. Further research is needed to identify the most appropriate, reliable and valid measures of perceived stroke risk and to determine if theory-based interventions designed to increase accuracy of perceived stroke risk influence healthy lifestyle choices for stroke risk reduction.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this paper in the form of providing protected time for the first author to conduct and oversee the review and manuscript preparation was supported in part by a K01 training grant from NIH/NINR (K01 NR015494).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Al Shafaee MA, Ganguly SS, Al Asmi AR. Perception of stroke and knowledge of potential risk factors among Omani patients at increased risk for stroke. BMC Neurology. 2006;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammouri A, Neuberger G. The Perception of Risk of Heart Disease Scale: Development and psychometric analysis. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2008;16(2):83–97. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.16.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Asimakopoulou KG, Skinner TC, Spimpolo J, Marsh S, Fox C. Unrealistic pessimism about risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;71(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aycock DM, Clark PC. Incongruence between perceived long-term risk and actual risk of stroke in rural African Americans. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2016;48(1):35–41. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aycock DM, Kirkendoll KD, Coleman KC, Clark PC, Albright K, Alexandrov AW. Family history of stroke among African Americans and its association with risk factors, knowledge, perceptions, and exercise. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2015;30:E1–E6. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baghal T. The measurement of risk perceptions: The case of smoking. The Journal of Risk Research. 2011;14:351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty P, Hermann D, Puskar C, Kerwin J. ‘Don’t know’ responses in surveys: Is what I know what you want to know and do I want you to know it? Memory. 1998;6:407–426. doi: 10.1080/741942605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden-Albala B, Carman H, Moran M, Doyle M, Paik MC. Perception of recurrent stroke risk among Black, White and Hispanic ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack survivors: The SWIFT study. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;37:83–87. doi: 10.1159/000329522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden-Albala B, Quarles L. Education strategies for stroke prevention. Stroke. 2013;44(6 Suppl 1):S48–S51. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer NT, Weinstein ND, Cuite CL, Herrington J. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:125–130. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL. Emotional health advertising and message resistance. Australian Psychologist. 2001;36:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. Perceptions of coronary heart disease: The development and psychometric testing of a measurement scale. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2014;19:159–168. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.802354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkmarket.com. Pitfalls of “don’t know/no opinion” answer options in surveys. 2016 Retrieved from https://www.checkmarket.com/blog/dont-know-no-opinion-answer-option/

- Christian A, Mochari H, Mosca L. Coronary heart disease in ethnically diverse women: Risk perception and communication. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2005;80:1593–1599. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearborn JL, McCullough LD. Perception of risk and knowledge of risk factors in women at high risk for stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1181–1186. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer RA, Klein WMP. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;5:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, Mensah GA, Connor M, Bennett DA, … Murray C. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61953-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiandt K, Pullen CH, Walker SN. Actual and perceived risk for chronic illness in rural older women. Clinical Excellence for Nurse Practitioners: The International Journal of NPACE. 1999;3:105–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournaise A, Skov J, Bladbjerg E, Leppin A. Stroke risk perception in atrial fibrillation patients is not associated with clinical stroke risk. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2015;24:2527–2532. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijling BD, Lobo CM, Keus IM, Jenks KM, Akkermans RP, Hulscher ML, … Grol RM. Perceptions of cardiovascular risk among patients with hypertension or diabetes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2004;52(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Descriptive studies: What they can and cannot do. Lancet. 2002;359:145–149. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond J, Salamonson Y, Davidson P, Everett B, Andrew S. Why do women underestimate the risk of cardiac disease? A literature review. Australian Critical Care. 2007;20:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwell TS, Blades LL, Oser CS, Dietrick DW, Okon NJ, Rodriguez DV, … Gohdes D. Perceived risk for developing stroke among older adults. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41:791–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JL, Ostroff J, Burkhalter J, Li Y, Quiles Z, Moadel A. Changes in cancer-related risk perception and smoking across time in newly-diagnosed cancer patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30:131–142. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman LL, Helden L, Chyun DA, Braun LT. A life course approach to cardiovascular disease prevention. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2011;10(Suppl 2):S20–S31. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(11)00113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imes C, Lewis F. Family history of cardiovascular disease, perceived cardiovascular disease risk, and health-related behavior: A review of the literature. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2014;29:108–129. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31827db5eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelewijn-van Loon MS, van der Weijden T, Ronda G, van Steenkiste B, Winkens B, Elwyn G, Grol R. Improving lifestyle and risk perception through patient involvement in nurse-led cardiovascular risk management: A cluster-randomized controlled trial in primary care. Preventive Medicine. 2010;50:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraywinkel K, Heidrich J, Heuschmann PU, Wagner M, Berger K. Stroke risk perception among participants of a stroke awareness campaign. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(39) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulshreshtha A, Vaccarino V, Judd S, Howard V, McClellan W, Muntner P, … Cushman M. Life’s Simple 7 and risk of incident stroke: The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Stroke. 2013;44:1909–1914. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkus I. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: Suggested best practices and future recommendations. Medical Decision Making. 2007;27:696–713. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07307271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx JJ, Klawitter B, Faldum A, Eicke BM, Haertle B, Dieterich M, Nedelmann M. Gender-specific differences in stroke knowledge, stroke risk perception and the effects of an educational multimedia campaign. Journal of Neurology. 2010;257(3):367–374. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx JJ, Nedelmann M, Haertle B, Dieterich M, Eicke BM. An educational multimedia campaign has differential effects on public stroke knowledge and care-seeking behavior. Journal of Neurology. 2008;255:378–384. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill H, McMahan C, Gidding S. Preventing heart disease in the 21st century: Implications of the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) study. Circulation. 2008;117:1216–1227. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, … Turner MB. Executive summary: Heart disease and stroke statistics--2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):447–454. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL. Development of the Perceived Risk of HIV scale. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(4):1075–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntaios G, Melikoki V, Perifanos G, Perlepe K, Gioulekas F, Karagiannaki A, … Dalekos GN. Poor stroke risk perception despite moderate public stroke awareness: Insight from a cross-sectional national survey in Greece. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2015;24:721–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers BJ, Danus S, Grubber JM, Olsen MK, Oddone EZ, Bosworth HB. The effectiveness of personalized coronary heart disease and stroke risk communication. American Heart Journal. 2011;161:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers BJ, Oddone EZ, Grubber JM, Olsen MK, Bosworth HB. Perceived and actual stroke risk among men with hypertension. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2008;10:287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal RN. Perceived risk and self-efficacy as motivators: Understanding individuals’ long-term use of health information. Journal of Communication. 2001;51:633–654. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R. A Protection Motivation Theory of fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of Psychology. 1975;91(1):93–114. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:328–335. doi: 10.1177/109019817800600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsa GP, Cohen SJ, Goldstein LB, Bonito AJ, Duncan PW, Enarson C, … Matchar DB. Knowledge of risk among patients at increased risk for stroke. Stroke. 1997;28(5):916–921. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.5.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P. Do adolescent smokers know the risks? Duke Law Journal. 1998;47(6):1133–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P. The perception of risk. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K, White K, Young R, Scott C. The Cerebrovascular Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (CABS-R): The factor structure and psychometric properties of a tool for assessing stroke-related health beliefs. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;17(1):67–73. doi: 10.1007/s12529-009-9047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth P, Willett D. Illness risk perceptions and trust: The association with blood pressure self-measurement. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2011;35:105–117. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Plight J. Risk perception and self-protective behavior. European Psychologist. 1996;1(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron C, van der Weijden T, Ludt S, Gallacher J, Elwyn G. What are effective strategies to communicate cardiovascular risk information to patients? A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;82(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, O’Neill SM, Rothrock N, Gramling R, Sen A, Acheson LS, … Ruffin MT. Comparison of risk perceptions and beliefs across common chronic diseases. Preventive Medicine. 2009;48:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Sen A, Ruffin M4, Nease DJ, Gramling R, Acheson LS, … Rubinstein WS. Family history assessment: Impact on disease risk perceptions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(4):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster R, Heeley E. Perceptions of risk: Understanding cardiovascular disease. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 2010;3:49–60. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal Personal Sociology & Psychology. 1980;39:806–820. [Google Scholar]

- Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The Extended Parallel Model. Communications Monographs. 1992;59:329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zheng M, Chen S, Ou S, Zhang J, Wang N, … Wang J. A survey of the perceived risk for stroke among community residents in western urban China. Plos One. 2013;8(9):e73578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]