Abstract

Nerve growth factor (NGF) has been implicated as an important mediator to induce C-fibre bladder afferent hyperexcitability, which contributes to the emergence of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) following spinal cord injury (SCI). In this study, we determined if NGF immunoneutralization using an anti-NGF antibody (NGF-Ab) normalizes the SCI-induced changes in electrophysiological properties of capsaicin-sensitive C-fibre bladder afferent neurones in female C57BL/6 mice. The spinal cord was transected at the Th8/9 level. Two weeks later, continuous administration of NGF-Ab (10 μg•kg−1 per hour, s.c. for 2 weeks) was started. Bladder afferent neurones were labelled with Fast-Blue (FB), a fluorescent retrograde tracer, injected into the bladder wall 3 weeks after SCI. Four weeks after SCI, freshly dissociated L6-S1 dorsal root ganglion neurones were prepared. Whole cell patch clamp recordings were then performed in FB-labelled neurones. After recording action potentials or voltage-gated K+ currents, the sensitivity of each neurone to capsaicin was evaluated. In capsaicin-sensitive FB-labelled neurones, SCI significantly reduced the spike threshold and increased the number of action potentials during 800 ms membrane depolarization. These SCI-induced changes were reversed by NGF-Ab. Densities of slow-decaying A-type K+ (KA) and sustained delayed rectifier-type K+ currents were significantly reduced by SCI. NGF-Ab reversed the SCI-induced reduction in the KA current density. These results indicate that NGF plays an important role in hyperexcitability of mouse capsaicin-sensitive C-fibre bladder afferent neurones due to KA channel activity reduction. Thus, NGF-targeting therapies could be effective for treatment of afferent hyperexcitability and neurogenic LUTD after SCI.

Keywords: Nerve growth factor, Spinal cord injury, Bladder afferent pathway

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) rostral to the lumbosacral level eliminates the voluntary and supraspinal control of voiding, leading initially to areflexic bladder and detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia (DSD), a loss of coordination between detrusor smooth muscle contraction and urethral sphincter relaxation. These conditions induce functional urethral obstruction, reduced voiding efficiency, urinary retention and subsequent bladder wall remodelling including hypertrophy, followed by the emergence of neurogenic detrusor overactivity (DO) (de Groat and Yoshimura, 2006, 2010, 2012; Samson and Cardenas, 2007).

It has been demonstrated that the SCI-induced phenotypic change of bladder afferent pathways is a pathophysiological basis of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) such as DO and DSD after SCI (de Groat and Yoshimura, 2010, 2012). Bladder afferent pathways consist of myelinated Aδ-fibres and unmyelinated C-fibres (Hulsebosch and Coggeshall, 1982; Uvelius and Gabella, 1998). In normal rats, Aδ-fibre but not C-fibre bladder afferents are involved in evoking the micturition reflex in an awake condition, while in chronic SCI rats, excitability of C-fibre bladder afferents is increased, thereby inducing neurogenic DO as evidenced by non-voiding bladder contraction (NVC) before micturition (de Groat and Yoshimura, 2006). These phenotypic changes of C-fibre bladder afferent pathways after SCI are supported by animal experiments using capsaicin pretreatment, which can induce desensitization of transient receptor potential (TRP) channel V1 (TRPV1)-expressing afferent pathways (Chuang et al., 2001; Maggi, 1993). Approximately 80% of neurofilament-poor C-fibre bladder afferent neurones from rats are sensitive to capsaicin (Yoshimura et al., 1998), and these capsaicin-sensitive neurones exhibit hyperexcitability after SCI evident as a decreased threshold for spike activation and increased rate of firing during membrane depolarization (Takahashi et al., 2013; Yoshimura and de Groat, 1997). On the other hand, a small proportion (5%) of neurofilament-rich Aδ-fibre bladder afferent neurones from rats respond to capsaicin (Yoshimura et al., 1998). Systemic treatment with capsaicin or resiniferatoxin, a more potent analogue of capsaicin, does not affect the initiation of the micturition reflex in normal awake rats but elicits a small increase in bladder capacity in normal urethane anesthetized rats (Maggi, 1993; Chuang et al., 2001). However in chronic SCI rats, capsaicin almost completely suppresses NVC without affecting the voiding reflex (Cheng et al., 1995; Cheng and de Groat, 2004) and also reduces DSD (Cheng and de Groat, 2004; Seki et al., 2004). Our recent study also showed in SCI mice that capsaicin treatment significantly reduces NVC during the storage phase and that capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones increase their excitability evident as increased firing frequency of action potentials during membrane depolarization (Kadekawa et al., 2017). Thus, SCI-induced hyperexcitability of capsaicin-sensitive C-fibre bladder afferent pathways is considered to be an important mechanism underlying neurogenic LUTD after SCI.

Neurotrophic factors including nerve growth factor (NGF) have been implicated as key molecules of pathology-induced changes in C-fibre afferent nerve excitability (de Groat and Yoshimura, 2010, 2012; Ochodnický et al., 2011). In normal rats, chronic administration of NGF into the lumbosacral spinal cord or into the bladder induces DO and increases the firing rate of dissociated capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones (Lamb et al., 2004; Yoshimura et al., 2006; Zvara and Vizzard, 2007). In SCI rats, NGF levels are increased in the bladder and in the lumbosacral spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) (Seki et al., 2002; Vizzard, 2006) and immunoneutralization of NGF in the lumbosacral spinal cord after SCI decreases DO and DSD in rats (Seki et al., 2002, 2004). An increase of NGF levels in the bladder mucosa was also detected at 4 weeks after SCI in mice (Wada et al., 2017c). These lines of evidence indicate the involvement of NGF in the SCI-induced emergence of neurogenic LUTD. However, there are no studies directly showing that NGF overexpression contributes to the changes in electrophysiological properties of bladder afferent neurones following SCI. Therefore, in the present study, using chronic SCI mice, we examined effects of NGF immunoneutralization on electrophysiological properties of capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones.

Methods

Ethical approval

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE and NIH guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) (Protocol approval #15086776). Efforts were made to minimize the suffering of the animals and the number of animals needed to obtain reliable results.

Animals

A total of 57 female C57BL/6 mice (9-10 weeks old, 18-22 g) (Harlan Laboratories Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA) were used in this study, and housed with four animals per cage upon the IACUC recommendation for humane animal care, maintained in an air-conditioned room at 22-24°C under the 12/12 h light-dark cycle with lights on at 07:00 AM, and given food (LabDiet #5P76, LabDiet, St. Louis, MO, USA) and water ad libitum. These mice were randomly divided into 3 groups: spinal intact group (SI, n=19), spinal cord injury group (SCI, n=18), and SCI group treated with anti-NGF antibody (NGF-Ab) (SCI+NGF-Ab, n=20).

Surgery

In SCI and SCI+NGF-Ab groups, the Th8/9 spinal cord of mice was completely transected under isoflurane anesthesia, as previously described (Kadekawa et al., 2017; Wada et al., 2017c). The bladder of these SCI mice was emptied by abdominal compression once a day after spinal cord transection. In the SCI+NGF-Ab group, 2 weeks after SCI, an osmotic mini pump (#1002, Alzet Osmotic Pumps, Cupertino, CA, USA) was placed subcutaneously in the back under isoflurane anesthesia for continuous delivery of mouse monoclonal NGF-Ab (#L148M, Exalpha Biologicals Inc., Shirley, MA, USA) at 10 μg•kg−1 per hour for 2 weeks. The dosage of the antibody was determined according to previous studies (Seki et al., 2002, 2004; Wada et al., 2017a) and our preliminary experiments. In order to label the population of DRG neurones innervating the bladder, a fluorescent retrograde axonal tracer Fast-Blue (FB, 1.8% w/w, PolySciences Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) was injected into the bladder wall of all animals under isoflurane anesthesia 7 days before dissociation of DRG neurones, as previously described (Kadekawa et al., 2017; Yoshimura et al., 2006). After each surgery and recovery from an anaesthetic, ketoprofen (5 mg•kg−1, s.c.) was given to all animals in order to control postoperative pain. Ampicillin (100 mg•kg−1, s.c.) was also administered to all animals for 3 days post-surgery in order to prevent urinary tract infection.

Dissociation of DRG neurones

Four weeks after SCI (SCI and SCI+NGF-Ab groups) or 7 days after the FB injection (SI group), isolated DRG neurones were prepared by enzymatic and mechanical dissociation methods as previously described (Kadekawa et al., 2017; Yoshimura et al., 2006) with slight modifications. Briefly, L6 and S1 DRG, which contain cell bodies of bladder afferents carried through the pelvic nerve, were dissected under isoflurane anesthesia, incubated in a bath for 12 min at 35.4°C with 5 ml of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 0.4 mg•ml−1 trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mg•ml−1 collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.1 mg•ml−1 DNase (Sigma-Aldrich). Trypsin inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich) was then added in order to neutralize the activity of trypsin. Individual DRG cell bodies were isolated by trituration and then plated on poly-L-lysine-coated 35 mm glass bottom culture dishes. These neurones were maintained in minimal essential medium (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with 10% (v/v) of fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and horse serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 U•ml−1 Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 0.5 mg•ml−1 DNase at 37°C in 5% CO2 per 95% air. After DRG removal, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation under isoflurane anesthesia.

Whole cell patch clamp recordings

FB-labelled primary afferent neurones that innervate the bladder were identified using an inverted phase contrast microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with fluorescent attachments (UV-1A filter; excitation wave length, 365 nm). Gigaohm-seal whole-cell recordings were performed at room temperature (20-22 °C) on freshly dissociated FB-labelled neurones in a culture dish. All recordings were performed with an Axopatch 200A patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA) within 24 h after dissociation, and data were acquired and analysed by pCLAMP software (Molecular Devices).

We first evaluated characteristics of action potentials in bladder afferent neurones from mice of each group, as previously described (Kadekawa et al., 2017; Yoshimura et al., 2006). The internal solution contained 140 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 11 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES and 2 mM Mg-ATP, adjusted to pH 7.4 with KOH (310 mOsm). Patch glass electrodes (10-20 μm tip diameter) had 2 to 4 MΩ resistance when filled with the internal solution. Neurones were superfused at a flow rate of 1.5 ml per minute with an external solution containing 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES and 10 mM D-glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH (340 mOsm).

When isolating K+ currents, as previously described (Yoshimura et al., 2006), neurones were superfused at a flow rate of 1.5 ml per minute with an external solution containing 110 mM choline-Cl, 5 mM KOH, 0.03 mM CaCl2, 3.4 mM Mg(OH)2, 10 mM HEPES and 10 mM D-glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with Trizma hydrochloride (340 mOsm) that suppresses Na+ and Ca2+ currents (Yoshimura and de Groat, 1999).

After evaluation of action potential characteristics or isolation of K+ currents, capsaicin sensitivity was evaluated by direct application of capsaicin (1 μM) to the neurones in a voltage-clamp mode with a holding potential (HP) at –60 mV. Inward shift of holding currents was observed in capsaicin-sensitive neurones. The stock solution of capsaicin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 5 mM containing 10% ethanol and 10% Tween 80 was prepared in the external solution described above for action potentials evaluation, and then diluted to the final concentration in the same external solution before experiments.

Data analysis

Cell membrane capacitances were obtained by reading the value for whole cell input capacitance neutralization directly from the amplifier.

In current-clamp recordings, data are presented from neurones that exhibited resting membrane potentials more negative than –40 mV and action potentials that overshot 0 mV. Durations of action potentials were measured at 50% of the spike amplitude. Thresholds for action potential activation were determined by injection of depolarizing current pulses in 20 pA steps. These data analyses were performed by investigators (S.T., E.T. and J.K.) blinded to experimental conditions. When examining the number of action potentials during 800-ms membrane depolarization, current intensity was set to the value just above the threshold for inducing spike activation with a 60-ms pulse.

In voltage-clamp recordings, the filter was set to −3 dB at 2,000 Hz. Leak currents were subtracted by P/4 pulse protocol, and the series resistance was compensated by 50–60%. The voltage error did not exceed 5 mV after compensation of the series resistance, and a charging time constant of the voltage clamp was <300 μs, which was faster than gating properties of outward K+ currents in this study. To correct the K+ current densities for cell size, the K+ current densities for each cell were normalized with respect to cell membrane capacitances that were obtained by reading the value for whole-cell input capacitance neutralization directly from the amplifier. Data were then analysed by pCLAMP software (Molecular Devices).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc analysis with the Bonferroni method. P values less than 0.05 were taken to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Effect of NGF-Ab treatment on excitability of bladder afferent neurones from mice with SCI

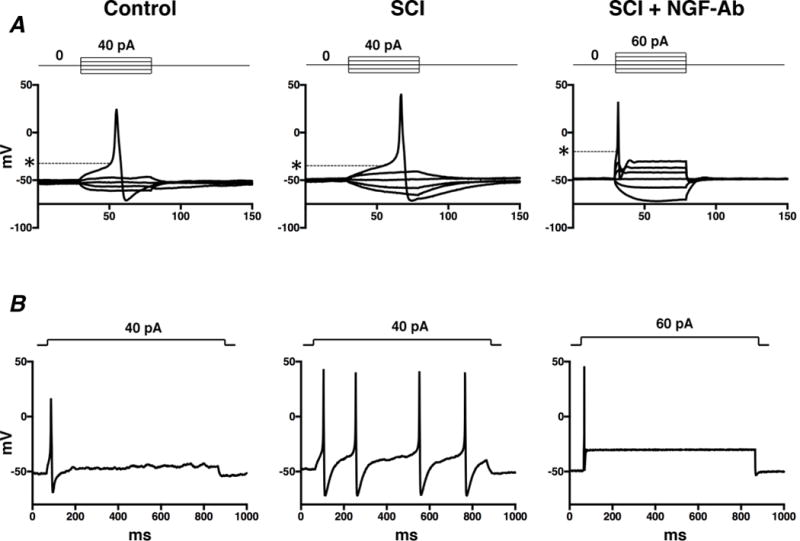

Figure 1 shows representative recordings of action potentials in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from 3 groups of mice. The resting membrane potentials and the peak and duration of action potentials did not differ among SI, SCI and SCI+NGF-Ab groups (Table 1). On the other hand, the threshold for eliciting action potentials was significantly reduced in neurones from SCI mice compared to neurones from SI mice (Figure 1A and Table 1). Also, the number of action potentials during 800-ms membrane depolarization in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from SCI mice was significantly increased compared to the number in neurones from SI mice (Figure 1B and Table 1). These SCI-induced changes were significantly reversed by 2-week treatment with NGF-Ab (10 μg•kg−1 per hour, s.c.) that was started 2 weeks after SCI (Figure 1 and Table 1). In addition, the diameter and cell input capacitance of capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from SCI mice were significantly greater than those from SI mice (Table 1); however, these SCI-induced changes were not affected by the NGF-Ab treatment (Table 1).

Figure 1. Representative action potential recordings in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from mice.

Dissociated mouse DRG neurones were prepared 4 weeks after spinal cord injury (SCI). Two weeks after spinal cord transection, some SCI mice were treated with anti-NGF antibody (10 μg•kg−1 per hour, s.c.) for 2 weeks (SCI+NGF-Ab). Spinal intact mice (SI) were used as controls. A, action potentials evoked by 60-ms depolarizing current pulses injected through glass patch pipettes during current clamp recordings. Asterisks with dashed lines indicate the thresholds for spike activation. B, firing patterns of action potentials during 800-ms membrane depolarization.

Table 1.

Electrophysiological properties of capsaicin sensitive bladder afferent neurons

| SI (Control) | SCI | SCI+NGF-Ab | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spikes: | |||

| Number of cells/mice | 17/11 | 22/9 | 19/13 |

| Diameter (μm) | 25.6 ± 4.5 | 29.1 ± 3.8* | 29.4 ± 2.8* |

| Input capacitance (pF) | 26.4 ± 8.9 | 36.7 ± 10.8* | 43.3 ± 5.7* |

| Resting membrane potentials (mV) | –50.0 ± 0.1 | –49.8 ± 0.3 | –49.7 ± 1.2 |

| Spike threshold (mV) | –24.3 ± 3.6 | –30.9 ± 5.2* | –22.3 ±7.4# |

| Peak membrane potential (mV) | 36.2 ± 11.0 | 37.1 ± 16.3 | 40.4 ± 19.4 |

| Spike duration (ms) | 3.9 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 2.6 |

| Number of spikes (800-ms depolarization) | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 5.5 ± 4.2* | 1.9 ± 1.6# |

| K+ current density: | |||

| Number of cells/mice | 23/8 | 25/9 | 18/7 |

| Slow decaying KA current density (pA/pF) | 45.5 ± 34.8 | 22.9 ± 15.3* | 50.0 ± 31.5# |

| Sustained KDR current density (pA/pF) | 117.4 ± 82.5 | 51.5 ± 28.8* | 58.5 ± 34.1* |

Values are means ± SD.

P < 0.05 and

P < 0.05, when compared with the Bonferroni method to the SI and SCI group, respectively.

KA, A-type K+; KDR, delayed rectifier-type K+; SCI, mice with spinal cord injury; SI, spinal cord intact mice; SCI+NGF-Ab, SCI mice treated with anti-NGF antibody (10 μg•kg−1 per hour, s.c.) for 2 weeks.

Effect of NGF-Ab treatment on K+ currents in bladder afferent neurones from mice with SCI

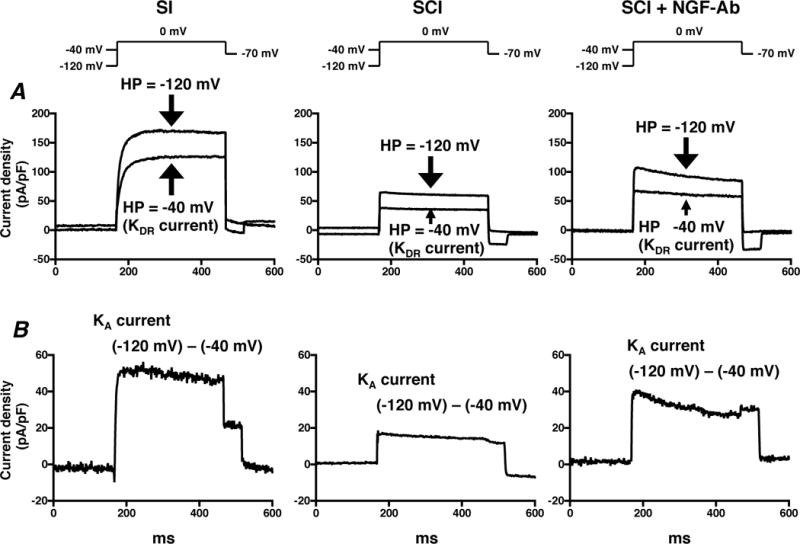

Figure 2 shows representative recordings of superimposed and estimated outward K+ currents in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from 3 groups of mice. Our previous reports indicated that slowly decaying A-type K+ (slow KA) currents in C-fibre bladder afferent neurones are activated by depolarizing voltage steps from hyperpolarized membrane potentials, but these currents are almost completely inactivated when membrane potentials are maintained at a depolarized level of greater than –40 mV (Yoshimura et al., 1996). Therefore, we estimated the density of slow KA currents by measuring the difference in the K+ currents evoked by depolarizing voltage pulses from HPs of –120 and –40 mV (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes of K+ currents in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from mice.

Dissociated mouse DRG neurones were prepared 4 weeks after spinal cord injury (SCI). Two weeks after spinal cord transection, some SCI mice were treated with anti-NGF antibody (10 μg•kg−1 per hour, s.c.) for 2 weeks (SCI+NGF-Ab). Spinal intact mice (SI) were used as controls. A, representative recordings show superimposed outward K+ currents evoked by depolarizing voltage pulses to 0 mV from a holding potentials (HPs) of –120 and –40 mV. Sustained delayed rectifier-type K+ (sustained KDR) currents were evoked by depolarization from –40 mV HP. B, slow decaying A-type K+ (slow KA) currents were obtained by subtracting K+ currents evoked by depolarization to 0 mV from HPs of –40 and –120 mV.

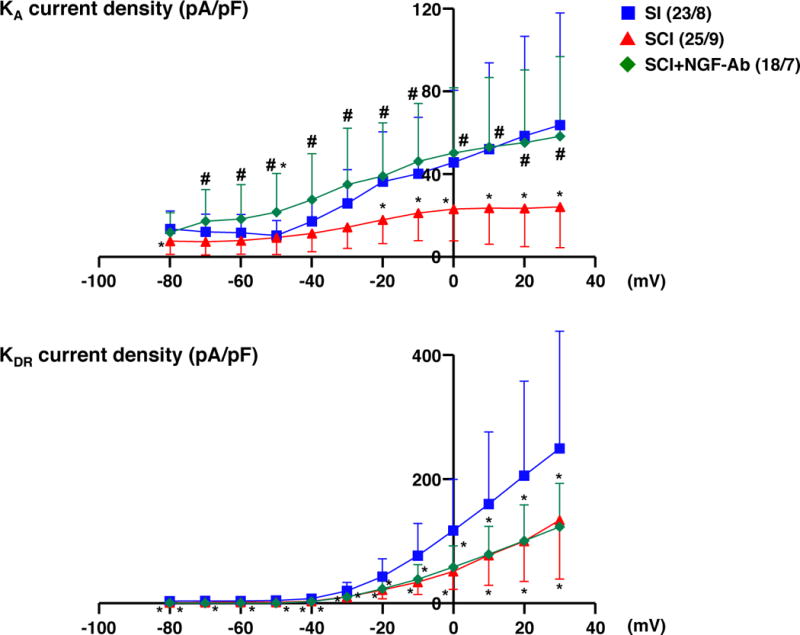

Densities of both slow KA and sustained delayed rectifier-type K+ (sustained KDR) currents were measured during membrane depolarization to 0 mV in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from 3 groups of mice (Figure 3). As shown in Table 1, the peak density of slow KA currents was obtained by measuring the difference in outward currents evoked from HPs of –40 and –120 mV, and the peak density of sustained KDR currents was measured by evoking a depolarization to 0 mV from a HP of –40 mV. The densities of slow KA and sustained KDR currents were significantly lower in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from SCI mice than those in neurones from SI mice (Table 1 and Figures 2–3). There were significant differences between the peak densities of slow KA and sustained KDR currents in neurones from SI and SCI mice at depolarizing pulses greater than –20 mV for slow KA currents and –40 mV for sustained KDR currents (Figure 3). Two-week treatment with NGF-Ab (10 μg•kg−1 per hour, s.c.) that was started 2 weeks after SCI significantly reversed the SCI-induced changes in the density of slow KA currents, but not of sustained KDR currents (Table 1 and Figures 2–3).

Figure 3. I-V relationships of K+ currents in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from mice.

Dissociated mouse DRG neurones were prepared 4 weeks after spinal cord injury (SCI). Two weeks after spinal cord transection, some SCI mice were treated with anti-NGF antibody (10 μg•kg−1 per hour, s.c.) for 2 weeks (SCI+NGF-Ab). Spinal intact mice (SI) were used as controls. Values present means ± SD. *P < 0.05, significant difference between SI and SCI groups, one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc analysis with the Bonferroni method. #P < 0.05, significant difference between SCI and SCI+NGF-Ab groups, one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc analysis with the Bonferroni method. The number of neurones/mice per group is indicated in parentheses.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that (1) capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from SCI mice showed hyperexcitability, evident as decreased spike thresholds and increased firing rate of action potentials compared to neurones from SI mice, (2) slow KA and sustained KDR current densities of capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from SCI mice were decreased compared to those from SI mice, and (3) immunoneutralization of NGF by NGF-Ab treatment for 2 weeks significantly reversed SCI-induced changes of spike thresholds, firing rate and slow KA current density. These results indicate that NGF has an essential pathophysiological role in SCI-induced hyperexcitability of capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones, and that the NGF-induced hyperexcitability may be induced via the reduction of KA channel activity.

Recently, we reported that, in mice, SCI induces a decrease in spike thresholds and an increase in the firing rate of capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones, and that systemic capsaicin pretreatment decreases the number of NVCs during the storage phase in SCI mice (Kadekawa et al., 2017). These data indicate that, similar to rats (Cheng et al., 1995; Cheng and de Groat, 2004; Takahashi et al., 2013), SCI-induced hyperexcitability of capsaicin-sensitive C-fibre bladder afferent pathways can contribute to the emergence of neurogenic DO after SCI in mice. Furthermore, we recently confirmed that in SCI mice, chronic NGF-Ab treatment starting 2 weeks after SCI normalizes the SCI-induced increase in NGF levels in the bladder and L6-S1 spinal cord, and decreases the number of NVCs (Wada et al., 2017a). In this study, the same NGF-Ab treatment protocol suppressed SCI-induced hyperexcitability in dissociated mouse capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones evident as reversal of the SCI-induced decrease in spike thresholds and increase in firing rate of these neurones. Therefore, the current study demonstrated for the first time that NGF directly contributes to hyperexcitability of capsaicin-sensitive C-fibre bladder afferent neurones, which underlies SCI-induced neurogenic DO.

Spike thresholds and firing rate of neurones are regulated by voltage-gated K+ channel (KV) activity. In sensory neurones, KV currents are divided into two major categories, transient KA and sustained KDR currents (Gold et al., 1996; Hall et al., 1994; Yoshimura et al., 1996; Yang et al., 2004). Transient KA currents in sensory neurones including DRG cells can be further subdivided into at least two subtypes based on their inactivation kinetics, i.e., fast- and slow-decaying KA currents (Akins and McCleskey, 1993; Everill and Kocsis, 1999; Gold et al., 1996; McFarlane and Cooper, 1991). The slow KA current is preferentially expressed in small-sized DRG neurones that exhibit capsaicin sensitivity and tetrodotoxin-resistant action potentials (Gold et al., 1996; Yoshimura et al., 1996; Yoshimura and de Groat, 1999). Thus, sustained KDR and slow KA currents can be involved in modulating excitability in small-sized C-fibre afferent neurones. We have already reported that 4-aminopyridine, a KA channel blocker, increases excitability of rat capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones as evidenced by lower spike threshold and increased firing rate (Yoshimura and de Groat, 1999), and that the reduction in slow KA currents was also observed in these neurones from SCI rats (Takahashi et al., 2013). In this study, we confirmed that densities of both sustained KDR and slow KA currents are decreased in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones from SCI mice. These results suggest that the reduction in these KV currents may be one of the key events underlying the hyperexcitability of C-fibre afferent neurones innervating the bladder in SCI mice. On the other hand, in SCI rats, the density of slow KA, but not sustained KDR, currents was decreased (Takahashi et al., 2013); therefore, it is likely that there are some differences between mice and rats in the mechanisms involved in the changes of KDR channel activities after SCI. This difference will be examined in more detail in future experiments.

In SCI mice, the decreased slow KA current density in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones was almost completely reversed by 2-week NGF-Ab treatment started 2 weeks after SCI whereas the treatment had no effect on the reduced sustained KDR currents density in these neurones. Furthermore administration of NGF into the lumbosacral spinal cord in SI rats decreased the density of slow KA, but not sustained KDR, currents in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones in rats (Yoshimura et al., 2006). These findings suggest that increased NGF after SCI is an important mediator of C-fibre bladder afferent neurone hyperexcitability due to reduction in KA, but not KDR, channel activity in both mice and rats. However, unlike rats, KDR channel activity seems to be decreased after SCI in mouse capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones by NGF-independent mechanisms. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a neurotrophic factor that enhances excitability of rat primary sensory neurones by suppressing the KDR current (Zhang et al., 2008). It has also been speculated that BDNF is a mediator of SCI-induced neurogenic LUTD because BDNF sequestration reduces neurogenic DO in chronic SCI (Frias et al., 2015). Also, we recently found that in SCI mice, BDNF antibody treatment reversed SCI-induced increase in BDNF levels in the bladder and suppressed DSD (Wada et al., 2017b). Therefore, in SCI mice, various neurotrophic factors including NGF and BDNF might be intricately involved in the emergence of neurogenic LUTD through a reduction in KV (KDR and KA) channel activity in C-fibre bladder afferent neurones although further studies are need to clarify these points.

After SCI, morphological changes have been detected in bladder afferent neurones. For example, somal hypertrophy is induced by SCI in capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones evident as increases in diameter and cell input capacitance, which is proportional to cell surface area (Kruse et al., 1995; Takahashi et al., 2013; Yoshimura and de Groat, 1997; Kadekawa et al., 2017). In addition, we recently reported using herpes simplex virus vectors with cell type-specific promoters that SCI induces expansion of C-fibre bladder afferent neurone populations that express TRPV1 or calcitonin gene-related peptide in mice (Shimizu et al., 2017). These morphological and chemical changes may be induced by NGF because (1) chronic administration of NGF into the lumbosacral spinal cord in SI rats increases the diameter and cell input capacitance of capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones (Yoshimura et al., 2006), and (2) autoimmunization against NGF suppresses somal hypertrophy of these neurones in rats with bladder outlet obstruction (Steers et al., 1991, 1996), which mimics the functional urethral obstruction induced by DSD in SCI. In the present study, however, chronic NGF-Ab treatment did not alter the SCI-induced increases in diameter and cell input capacitance in mouse capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones. A limitation of this study is the delay in the start of the NGF-Ab treatment. The antibody treatment was started 2 weeks after SCI in this study; whereas somal hypertrophy was detected in bladder afferent neurones from SI rats after 2 weeks of NGF treatment (Yoshimura et al., 2006). If somal hypertrophy was already established before starting the antibody treatment in SCI mice, the timing of intervention might be unable to reverse SCI-induced morphological changes in mouse capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones. Therefore, it is necessary to examine a time-dependent effect of NGF-Ab treatment for SCI-induced morphological and functional changes in mouse bladder afferent neurones in future.

In summary, our results indicate that NGF plays an important role in hyperexcitability of capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones due to the reduction in KA channel activity in SCI mice. The results provide evidence that NGF-targeting therapies can be effective for treatment of the afferent hyperexcitability and neurogenic LUTD in SCI.

New Findings.

What is the central question of this study?

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is reportedly an important mediator inducing urinary bladder dysfunction. However, it is not known whether NGF is directly involved in hyperexcitability of capsaicin-sensitive C-fibre bladder afferent pathways after spinal cord injury (SCI), which underlies SCI-induced bladder overactivity.

What is the main finding and its importance?

This electrophysiologic study showed, for the first time, that NGF neutralization by anti-NGF antibody treatment reversed the SCI-induced increase in the number of action potentials, and the reduction in spike thresholds and A-type K+ current density in mouse capsaicin-sensitive bladder afferent neurones. Thus, NGF plays an important and direct role in hyperexcitability of capsaicin-sensitive C-fibre bladder afferent neurones due to the reduction in A-type K+ channel activity in SCI.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney (P01-DK093424 to N.Y.) and a Grant from the Department of Defence (W81XWH-17-1-0403 to N.Y.).

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DO

detrusor overactivity

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- DSD

detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia

- FB

Fast-Blue

- HP

holding potential

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees

- KA

A-type K+

- KDR

delayed rectifier-type K+

- KV

voltage-gated K+

- LUTD

lower urinary tract dysfunction

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- NGF-Ab

anti-nerve growth factor antibody

- NVC

non-voiding bladder contraction

- SCI

spinal cord injury

- SI

spinal intact

- slow KA

slow decaying A-type K+

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential channel V1

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

T. Shimizu, T.M. T. Suzuki and N.Y. created this research design. T. Shimizu, T.M. and T. Suzuki performed electrophysiological experiments. T. Shimizu, T.M., T. Suzuki, N.S., N.W. and K.K. performed SCI surgery. T. Shimizu, T.M., T. Suzuki, N.S., N.W., K.K., S.T., E.T. and J.K. cared SCI mice. T. Shimizu, T.M., T. Suzuki, S.T., E.T. and J.K analysed data. T. Shimizu, T.M. T. Suzuki and N.Y. interpreted results of experiments. T. Shimizu, T.M., T. Suzuki, A.J.K., W.C.d.G., P.T., M.S. and N.Y. drafted manuscript. T. Shimizu, T.M., T. Suzuki, N.S., N.W., N.S., K.K., S.T., E.T., J.K., A.J.K., W.C.d.G., P.T., M.S. and N.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

References

- Akins PT, McCleskey EW. Characterization of potassium currents in adult rat sensory neurons and modulation by opioids and cyclic AMP. Neuroscience. 1993;56:759–769. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90372-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CL, de Groat WC. The role of capsaicin-sensitive afferent fibers in the lower urinary tract dysfunction induced by chronic spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CL, Ma CP, de Groat WC. Effect of capsaicin on micturition and associated reflexes in chronic spinal rats. Brain Res. 1995;678:40–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YC, Fraser MO, Yu Y, Beckel JM, Seki S, Nakanishi Y, de Groat WC. Analysis of the afferent limb of the vesicovascular reflex using neurotoxins, resiniferatoxin and capsaicin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1302–R1310. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.4.R1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Mechanisms underlying the recovery of lower urinary tract function following spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:59–84. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Changes in afferent activity after spinal cord injury. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:63–76. doi: 10.1002/nau.20761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Plasticity in reflex pathways to the lower urinary tract following spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2012;235:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everill B, Kocsis JD. Reduction in potassium currents in identified cutaneous afferent dorsal root ganglion neurons after axotomy. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:700–708. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.2.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias B, Santos J, Morgado M, Sousa MM, Gray SM, McCloskey KD, Cruz CD. The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the development of neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO) J Neurosci. 2015;35:2146–2160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MS, Shuster MJ, Levine JD. Characterization of six voltage-gated K+ currents in adult rat sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2629–2646. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A, Stow J, Sorensen R, Dolly JO, Owen D. Blockade by dendrotoxin homologues of voltage-dependent K+ currents in cultured sensory neurones from neonatal rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:959–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsebosch CE, Coggeshall RE. An analysis of the axon populations in the nerves to the pelvic viscera in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1982;211:1–10. doi: 10.1002/cne.902110102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadekawa K, Majima T, Shimizu T, Wada N, de Groat WC, Kanai AJ, Yoshimura N. The role of capsaicin-sensitive C-fiber afferent pathways in the control of micturition in spinal intact and spinal cord injured mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;313:F796–F804. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00097.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse MN, Bray LA, de Groat WC. Influence of spinal cord injury on the morphology of bladder afferent and efferent neurons. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;54:215–224. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00011-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb K, Gebhart GF, Bielefeldt K. Increased nerve growth factor expression triggers bladder overactivity. J Pain. 2004;5:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi CA. The dual, sensory and efferent function of the capsaicin-sensitive primary sensory nerves in the bladder and urethra. In: Maggi CA, editor. Nervous control of the urogenital system. London, UK: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1993. pp. 383–422. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane S, Cooper E. Kinetics and voltage dependence of A-type currents on neonatal rat sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:1380–1391. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.4.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochodnický P, Cruz CD, Yoshimura N, Michel MC. Nerve growth factor in bladder dysfunction: contributing factor, biomarker, and therapeutic target. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:1227–1241. doi: 10.1002/nau.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson G, Cardenas DD. Neurogenic bladder in spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18:255–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S, Sasaki K, Fraser MO, Igawa Y, Nishizawa O, Chancellor MB, Yoshimura N. Immunoneutralization of nerve growth factor in lumbosacral spinal cord reduces bladder hyperreflexia in spinal cord injured rats. J Urol. 2002;168:2269–2274. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64369-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S, Sasaki K, Igawa Y, Nishizawa O, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Suppression of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia by immunoneutralization of nerve growth factor in lumbosacral spinal cord in spinal cord injured rats. J Urol. 2004;171:478–482. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000088340.26588.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu N, Doyal MF, Goins WF, Kadekawa K, Wada N, Kanai AJ, Yoshimura N. Morphological changes in different populations of bladder afferent neurons detected by herpes simplex virus (HSV) vectors with cell-type-specific promoters in mice with spinal cord injury. Neuroscience. 2017;364:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steers WD, Creedon DJ, Tuttle JB. Immunity to nerve growth factor prevents afferent plasticity following urinary bladder hypertrophy. J Urol. 1996;155:379–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steers WD, Kolbeck S, Creedon D, Tuttle JB. Nerve growth factor in the urinary bladder of the adult regulates neuronal form and function. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1709–1715. doi: 10.1172/JCI115488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R, Yoshizawa T, Yunoki T, Tyagi P, Naito S, de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Hyperexcitability of bladder afferent neurons associated with reduction of Kv1.4 α-subunit in rats with spinal cord injury. J Urol. 2013;190:2296–2304. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvelius B, Gabella G. The distribution of intramural nerves in urinary bladder after partial denervation in the female rat. Urol Res. 1998;26:291–297. doi: 10.1007/s002400050060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA. Neurochemical plasticity and the role of neurotrophic factors in bladder reflex pathways after spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:97–115. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada N, Shimizu T, Shimizu N, Tyagi P, de Groat W, Kanai A, Yoshimura N. Roles of nerve growth factor in bladder storage dysfunction due to detrusor overactivity in spinal cord injured mice – analysis of time-dependent responses. J Urol. 2017a;197:e1147–e1148. [Google Scholar]

- Wada N, Shimizu T, Shimizu N, Tyagi P, de Groat W, Kanai A, Yoshimura N. Neutralization of brain-derived neurotrophic factor increases synergistic activity of external urethral sphincter with reduction of acid-sensing ion channels in mice with spinal cord injury. J Urol. 2017b;197:e1907–e1908. [Google Scholar]

- Wada N, Shimizu T, Takai S, Shimizu N, Kanai AJ, Tyagi P, Yoshimura N. Post-injury bladder management strategy influences lower urinary tract dysfunction in the mouse model of spinal cord injury. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017c;36:1301–1305. doi: 10.1002/nau.23120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang EK, Takimoto K, Hayashi Y, de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Altered expression of potassium channel subunit mRNA and alpha-dendrotoxin sensitivity of potassium currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons after axotomy. Neuroscience. 2004;123:867–874. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, Bennett NE, Hayashi Y, Ogawa T, Nishizawa O, Chancellor MB, Seki S. Bladder overactivity and hyperexcitability of bladder afferent neurons after intrathecal delivery of nerve growth factor in rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10847–10855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3023-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, de Groat WC. Plasticity of Na+ channels in afferent neurons innervating rat urinary bladder following spinal cord injury. J Physiol. 1997;503:269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.269bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, de Groat WC. Increased excitability of afferent neurons innervating rat urinary bladder after chronic bladder inflammation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4644–4653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04644.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, Erdman SL, Snider MW, de Groat WC. Effects of spinal cord injury on neurofilament immunoreactivity and capsaicin sensitivity in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons innervating the urinary bladder. Neuroscience. 1998;83:633–643. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00376-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, White G, Weight FF, de Groat WC. Different types of Na+ and A-type K+ currents in dorsal root ganglion neurones innervating the rat urinary bladder. J Physiol. 1996;494:1–16. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YH, Chi XX, Nicol GD. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances the excitability of rat sensory neurons through activation of the p75 neurotrophin receptor and the sphingomyelin pathway. J Physiol. 2008;586:3113–3127. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.152439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvara P, Vizzard MA. Exogenous overexpression of nerve growth factor in the urinary bladder produces bladder overactivity and altered micturition circuitry in the lumbosacral spinal cord. BMC Physiol. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]