Abstract

PURPOSE

To determine if use of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is associated with an increased fracture risk, as some prior studies have suggested.

METHODS

This retrospective cohort study included data on 4,438 participants aged 65 and older who had no fracture in the year prior to baseline and had ≥5 years of enrollment history in Kaiser Permanente Washington, an integrated healthcare delivery system in Seattle, WA during 1994-2014. Time-varying cumulative exposure to PPIs was determined from automated pharmacy data by summing standard daily doses (SDDs) across fills, and patients were categorized as: no use (reference group, ≤ 30 SDD), light use (31-540 SDD), moderate use (541-1080 SDD) and heavy use (≥1081 SDD). Incident fractures were assessed using ICD-9 codes from electronic medical records. Potential confounders, chosen a priori, were assessed at baseline and at each 2-year follow-up visit. Fracture risk was analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model.

RESULTS

Over a mean follow-up of 6.1 years, 802 (18.1%) participants experienced a fracture. No overall association was found between PPI use and fracture risk. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) comparing users to the referent category were 1.08 (95% CI 0.83-1.40) for light users, 1.31 (95% CI 0.86-1.95) for moderate users, and 0.95 (95% CI 0.68-1.34) for heavy users. Among patients with SSD > 30, no appreciable increase in fracture risk was present in persons with recent versus distant use (aHR of 1.14 [95% CI 0.91–1.42]).

CONCLUSIONS

No association was observed between PPI use and fracture risk among older adults.

Keywords: older adult, medications, comorbidity, fracture, proton pump inhibitor

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are used to treat gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) and gastric or duodenal ulcers.1 In the United States (US), six PPIs are currently available (Supplemental Table 1). About 30% of the adult population in the US utilizes PPIs, making them among the most commonly used drugs.2 Not only has PPI use increased since omeprazole became available over the counter (OTC) in 2003, but in recent years the duration of prescription use has also increased, resulting in numerous people taking these medications for several years or more.3

Fractures are an important outcome for older adults because these events often give rise to severe complications or mortality.4–6 It has been hypothesized that the use of PPIs increases the risk of fractures,7 as these medications target hydrogen and potassium ATPase pumps of gastric parietal cells, resulting in decreased stomach acidity. PPIs are thought to diminish bone mineral density (BMD) by effects on stomach acidity and the consequent reduction of calcium absorption, which might make someone more susceptible to fractures. To date, however, studies have not documented these changes in BMD among PPI users to support this hypothesis.7, 8

In addition to mechanistic uncertainties, the presence and magnitude of an association between PPI use and fractures in the epidemiologic literature is inconsistent, with some studies reporting an increased risk,2, 3, 9–11 while others report no associations12 or associations limited to only a sub-set of high-risk patients13 or a subset of fracture sites.7, 8 In studies observing an increased risk of fractures, many found associations with PPI use equivalent to 1 year or less.9, 13–15 However, the mechanism described previously would have a long induction period before clinically measurable effects on BMD or fracture risk would appear, making the presence of a causal association with rapid onset implausible unless by way of another mechanism.

The reasons for discrepant results among epidemiologic studies are not clear. A limitation of prior longitudinal studies is the reliance on administrative, claims-based data sources only. This type of data does not allow for adequate control of likely confounders such as concomitant medication use, exercise, body mass index (BMI), and tobacco use. Furthermore, the impact of cumulative dose rather than a binary variable for medication exposure on fracture risk has not been well evaluated.

The primary aim of this study was to examine the association between PPI use and the incidence of fractures. To address limitations of prior studies, the present study draws on data from a prospective cohort study, which allows for detailed measurement of PPI exposure, health behaviors, functional status measures, and medical histories of study participants which greatly enhances the ability to control for important confounding factors.

Methods

This study utilized data from a prospective cohort study of older adults enrolled in Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA) an integrated healthcare delivery system with approximately 600,000 members residing in the Pacific Northwest. The exposure of interest was cumulative use of PPI medications measured from electronic pharmacy data, and the outcome of interest was a fracture of the hip, forearm, humerus, clavicle or scapula, rib or sternum, tibia or fibula, or ankle, ascertained from electronic diagnosis data including emergency department, inpatient, and outpatient records.

Overview and setting

Participants were part of the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) cohort, a prospective cohort study at KPWA. ACT study methods have been described in detail elsewhere.17 A brief description of study methods follows; study participants were recruited from a random sample of Seattle-area members of KPWA who were 65 or older. Participants were required to be community-dwelling and cognitively intact at study entry. The original cohort of 2,581 men and women was enrolled between 1994 and 1996, followed by an additional 811 participants who were enrolled between 2000 and 2003 (the “expansion cohort”). Then, in 2004, the study began continuous enrollment (n=1,555 available for this study) to replace those who died or dropped out, resulting in a total of 4,947 participants as of the end of April, 2014, who were available for this study.

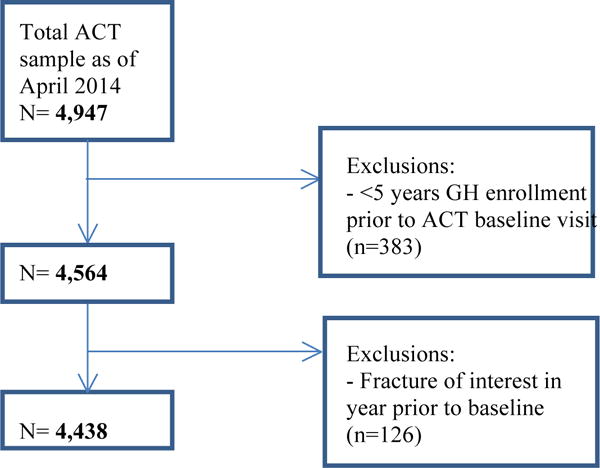

For the current analyses, participants were required to have 5 or more years of continuous KPWA membership before baseline to ensure more complete capture of exposure. Additionally, those sustaining a fracture of interest within one year prior to baseline were excluded to ensure the capture of only incident fractures. Applying these inclusion criteria yielded 4,438 participants (Figure 1). This research was approved by the KPWA Human Subjects Review Board, and all participants provided signed informed consent.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of selection of population for inclusion in study

Exposure measurement

The KPWA pharmacy database includes all prescriptions dispensed from KPWA pharmacies from March, 1977 to present, including drug name, strength, and quantity. In prior studies, 96% of older KPWA members have reported filling all or most of their prescriptions at a KPWA pharmacy.18 The exposure of interest was cumulative use of any PPI medication calculated by first converting each prescription to standard daily doses (SDDs) by multiplying the number of tablets dispensed by the tablet strength and dividing by the equivalent daily dose for each PPI prescription.19 All prescriptions starting 5 years prior to baseline and extending until the end of study were utilized to derive a time-varying measure of cumulative exposure for each participant that was non-decreasing and reflected changes as a person accrued exposure. Cumulative exposure was used because this measure has the most biologic plausibility for influencing fracture risk. Participants were categorized based on cumulative use: ≤30 SDD, 31-540 SDD, 541-1,080 SDD, ≥1,081 SDD, which corresponds to <1 month, 1-<19 months, 19-<36 months, or >=36 months of daily PPI use at the SDD. The referent group (≤30 SDD) includes people with no use as well as those with up to 1 month of PPI use. We include people who may have had very brief exposure for two reasons: first, there is a strong possibility that they may not have actually taken the medication. The frequency of this type of non-adherence is as high as 50% in some studies,20 and among PPI users specifically, non-adherence can be common.21 Furthermore, based on the proposed mechanisms by which PPI use could increase fracture risk, we believe that substantially more than 30 SDDs would be needed to cause a clinically meaningful impact on fracture risk.

In addition to pharmacy data, self-reported medication use was collected at ACT follow-up interviews every 2 years, including information about any OTC medications used, allowing us to identify participants reporting OTC PPI use, which otherwise would not have been identified.

Ascertainment of fracture

All participants who experienced a fracture of the hip, forearm, humerus, clavicle or scapula, rib or sternum, tibia or fibula, or ankle during follow-up were identified. Vertebral fractures were not included in the outcome definition because estimates show that up to 75% of individuals with vertebral fracture may not seek medical attention.16 Because of this, it is difficult to know when they occur. We did not limit our outcomes to study only fractures due to limited trauma, as work has shown that high-trauma fractures are associated with low bone mineral density and therefore a higher risk of subsequent fracture particularly among older adult populations.22 Ankle fractures, though sometimes not considered in studies of osteoporotic fractures, were included here because these fractures have features of osteoporotic fractures that are subject to age and gender-dependent low bone attenuation.23 We chose these fracture sites in part based on results from a prior validation study at KPWA (unpublished). That study examined women aged 45-59 enrolled in KPWA, with an inpatient or outpatient International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code (n=3,178) for fracture in their chart and age-matched controls (n=4374). Data were collected through interviews and detailed medical record reviews. Overall, ICD-9 codes for osteoporotic fractures (included fractures of the forearm, humerus, rib, sternum, scapula, clavicle, vertebra, pelvis, hip, femur, tibia/fibula, and ankle) had a PPV of approximately 80%. Furthermore, the sensitivity of ICD-9 codes was 83.7%, and specificity was 98.7%. The authors concluded that ICD-9 codes can be used to identify fractures in adults using large datasets due to the high sensitivity and specificity, but there will be some misclassification with fractures of the rib, spine, or a non-specific location. In the present study, fractures were identified using electronic health data by searching for one or more relevant ICD-9 diagnosis codes 807, 810-814,820, 823, and 824 in inpatient, outpatient or emergency department records.

Potential confounders

At study baseline and follow-up visits, information on covariates was collected. Demographic factors included age, sex, and race. Medical history included self-reported data on epilepsy, vision problems, stroke, congestive heart failure, and coronary heart disease (CHD), with CHD defined as a self-reported history of myocardial infarction, angina, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG,) or angioplasty. Pharmacy data were used to identify treated diabetes or hypertension based on 2 or more pharmacy fills for antihypertensive medications, insulin or other oral diabetes medications in any 12-month period. Health-related factors included body mass index (BMI) calculated from measured height and weight, self-rated health (fair/poor vs. excellent/very good/good), smoking (never/former/current), Charlson comorbidity index (Deyo adaptation24) and physical activity (PA) frequency. Depression status was also considered with participants categorized as depressed if their score was 10 or more on a modified version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CESD).25 Cognition was measured using the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI). A person was determined to have cognitive impairment if their score fell below 86 on this 100-point test or was referred for detailed evaluation by study interviewers.26 Functional status was measured, including difficulty with activities of daily living (ADLs) or with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Additionally, low gait speed, defined as less than 0.6 meters/second, was measured because of its implications as a clinical marker for functional capacity in older adults.27

We also used computerized pharmacy data to define time-varying exposure to medications that might confound the association under study. For medications associated with fracture risk based on past or sustained use (bisphosphonates, corticosteroids, histamine-2 receptor antagonists [H2RAs], and hormone replacement therapy [HRT]), a person was defined as a user in a time-varying fashion beginning at the time they filled their second prescription. Once a participant met this exposure criterion, they were considered “exposed” to that medication for the remainder of follow-up. For medications associated with fracture risk based on recent use (prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), benzodiazepines, antidepressants, thiazide diuretics, opioids, and anticonvulsants), a person was defined as a user if they had a fill for a given medication class within the prior 30 days.

Statistical Analyses

Cohort characteristics were presented stratified according to baseline level of PPI use, with means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Additionally, person-time was calculated based on the time a participant contributed to a given category of exposure, allowing the presentation of proportions of person-time for each covariate. To analyze the association between PPI exposure and risk of fracture, hazard ratios (HRs) from Cox proportional hazards regression models were estimated using time since ACT entry as the time scale. Participants were followed until the earliest first fracture or a censoring event. Censoring events in this analysis include disenrollment from ACT or KPWA, dementia onset, one year after final ACT visit, death, or end of ACT study period (April 30, 2014). Participants were censored one year after their final ACT visit to ensure that covariate information from a recent ACT visit was available for analysis. Potential confounders were selected for the models a priori, based on review of the literature and clinical plausibility.

Models adjusted for age, sex, epilepsy, treated diabetes, treated hypertension, depression, impaired cognition, vision problems, stroke, CHF, CHD, difficulty with ADLs, difficulty with IADLs, low gait speed, exercise, BMI, smoking, self-rated health, Charlson comorbidity index, and use of: bisphosphonates, corticosteroids, prescription NSAIDs, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, thiazide diuretics, HRT, H2RAs, prescription opioids and anticonvulsants.

We conducted additional analyses to evaluate the possible influence of age (>75 versus ≤75) or sex on the association between PPI use and fracture risk. For these analyses we estimated two additional adjusted models, one including an interaction between age and exposure and another with an interaction between sex and exposure. Lastly, we tested the effect that recency of PPI use might have on fracture risk. For this recency analysis, the sample was restricted to those who were exposed to PPIs during the study period. Recent users were defined as those who were exposed to PPIs during the year prior to an event and distant users were those who had not been exposed to PPIs in the year prior to an event. We also tested whether there was evidence of an interaction between cumulative exposure and recency of use. In addition, we conducted a posthoc sensitivity analysis examining current use, which we defined as a fill for a PPI medication with the past 30 days.

Complete case analysis methods were used. The assumption of proportionality of hazards was tested by examining Schoenfeld residuals. All analyses were performed using STATA version 13. Before beginning the study, we conducted power calculations which showed we would be powered to detect a hazard ratio of 1.2 or greater for the association between binary PPI use (yes/no) and fracture risk in our cohort.

Results

There were a total of 4,438 participants with a median age of 74.0 years (interquartile range (IQR) 69.8-79.5) at study entry, 58% of whom were women. Table 1 provides baseline characteristics of all study participants. Additionally, Table 2 provides a breakdown of the proportion of total person-time based on various participant characteristics and PPI exposure category. Since the exposure was time-varying, each participant was able to contribute person-time to multiple exposure categories depending on changes in cumulative dose of exposure.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic* | Study participants N= 4,438 |

|---|---|

| Age, median (25th, 75th) | 74.0 (69.8, 79.5) |

| Female | 2,575 (58.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 3,981 (89.7) |

| Black | 168 (3.8) |

| Asian | 138 (3.1) |

| Other, including mixed | 147 (3.3) |

| Epilepsy | 34 (0.8) |

| Treated diabetes† | 390 (8.8) |

| Treated hypertension† | 2,435 (54.9) |

| Depression‡ | 424 (9.6) |

| Impaired cognition | 253 (5.7) |

| Vision problems | 657 (14.8) |

| Stroke | 129 (2.9) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 167 (3.8) |

| Coronary Artery Disease§ | 796 (18.0) |

| Low gait speed¶# | 392 (8.8) |

| Difficulty with ≥1 ADL#% | 951 (21.4) |

| Difficulty with ≥1 IADL#% | 652 (14.7) |

| Regular exercise | 3,136 (70.7) |

| BMI, median (25th, 75th) | 26.7 (24.0-30.1) |

| Smoking Never | 2,139 (48.2) |

| Former | 2,067 (46.6) |

| Current | 220 (5.0) |

| Fair or poor self-rated health | 675 (15.2) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (std. deviation) | 1.58 (0.92) |

| Fracture in past 5 years | 224 (5.1) |

| Opioidsx | 193 (4.4) |

| Anticonvulsantsx | 47 (1.1) |

| Benzodiazepinesx | 124 (2.8) |

| Prescription NSAIDsx | 217 (4.9) |

| Antidepressantsx | 254 (5.7) |

| Thiazide diureticsx | 302 (6.8) |

| Bisphosphonates† | 235 (5.3) |

| Corticosteroids† | 401 (9.0) |

| H2RAs† | 867 (19.5) |

| Hormone therapy (limited to women)† | 925 (35.9) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living, H2RA, histamine type2 receptor antagonist, NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Results are provided as n (%) unless otherwise stated. Less than 5% of people had missing values;

Defined from computerized pharmacy data as filling ≥2 prescriptions;

Defined as a score of ≥10 on a modified version of the CESD scale;

Defined as scoring below 86 (out of 100 possible points) on the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument test or being referred by study interviewers for detailed cognitive evaluation within the research study;

Defined as a self-reported history of myocardial infarction, angina, CABG, or angioplasty;

Based on walk speed of <0.6 meters/second;

Ascertained at baseline;

Defined as trouble with ≥1 ADL or IADL;

Defined from pharmacy data as having a fill within prior 30 days

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with varying levels of PPI exposure: proportion of accumulated person time

| Characteristic* | ≤ 30 SDD (n=22,852 person-years) |

31-540 SDD (n=2,144 person-years) |

541-1080 SDD (n= 697 person-years) |

≥ 1080 SDD (n= 1,530 person-years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 65-69 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 3.3 | 4.6 |

| 70-74 | 23.6 | 15.7 | 16.0 | 16.0 |

| 75-79 | 28.5 | 27.1 | 26.0 | 21.8 |

| 80-84 | 23.0 | 27.0 | 31.0 | 27.8 |

| ≥ 85 | 17.2 | 25.1 | 23.7 | 29.9 |

| Female | 57.6 | 64.6 | 54.6 | 57.6 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 90.0 | 88.0 | 89.2 | 88.3 |

| Black | 4.0 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 6.1 |

| Asian | 3.5 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Other, including mixed | 2.4 | 5.6 | 2.5 | 3.3 |

| Epilepsy | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Treated diabetes† | 9.8 | 12.1 | 12.9 | 12.2 |

| Treated hypertension† | 63.5 | 78.4 | 78.9 | 84.7 |

| Depression‡ | 7.8 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 11.9 |

| Impaired cognition | 4.8 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 6.3 |

| Vision problems | 26.2 | 31.5 | 35.6 | 32.7 |

| Stroke | 3.2 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 3.4 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 4.7 | 7.2 | 8.4 | 13.1 |

| Coronary Artery Disease§ | 19.9 | 33.4 | 34.1 | 37.0 |

| Low gait speed¶# | 6.1 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 8.1 |

| Difficulty with ≥1 ADL#% | 17.4 | 24.8 | 24.9 | 28.6 |

| Difficulty with ≥1 IADL#% | 11.1 | 15.1 | 15.6 | 15.9 |

| Regular exercise | 66.2 | 60.9 | 58.1 | 58.6 |

| BMI | ||||

| <18.5 (underweight) | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| 18.5-24.9 (normal) | 33.2 | 29.3 | 29.3 | 26.1 |

| 25.0-29.9 (overweight) | 41.0 | 42.5 | 42.4 | 45.8 |

| ≥30.0 (obese) | 24.5 | 27.4 | 26.7 | 26.3 |

| Smoking-Never | 49.0 | 48.9 | 40.2 | 46.7 |

| Former | 46.4 | 48.2 | 57.5 | 50.6 |

| Current | 4.1 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Fair or poor self-rated health | 14.0 | 21.2 | 25.3 | 21.5 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| 0 | 63.6 | 45.8 | 44.0 | 41.8 |

| 1 | 17.7 | 22.8 | 22.3 | 22.1 |

| 2 | 11.3 | 15.4 | 14.5 | 15.5 |

| 3+ | 7.4 | 16.0 | 19.2 | 20.7 |

| Fracture in past 5 years | 3.9 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.3 |

| Opioidsx | 2.8 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 8.1 |

| Anticonvulsantsx | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| Benzodiazepinesx | 2.0 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| Prescription NSAIDsx | 5.2 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 9.3 |

| Antidepressantsx | 4.2 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 9.7 |

| Thiazide diureticsx | 6.0 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 8.5 |

| Bisphosphonates† | 8.0 | 17.0 | 18.3 | 19.8 |

| Corticosteroids† | 12.2 | 21.4 | 20.9 | 21.7 |

| H2RAs† | 21.7 | 61.3 | 71.2 | 67.6 |

| Hormone therapy (limited to women)† | 26.3 | 33.9 | 31.6 | 33.1 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living, H2RA, histamine type2 receptor antagonist, NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Results are provided as n (%) unless otherwise stated. Less than 5% of people had missing values;

Defined from computerized pharmacy data as filling ≥2 prescriptions;

Defined as a score of ≥10 on a modified version of the CESD scale;

Defined as scoring below 86 (out of 100 possible points) on the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument test or being referred by study interviewers for detailed cognitive evaluation within the research study;

Defined as a self-reported history of myocardial infarction, angina, CABG, or angioplasty

Based on walk speed of <0.6 meters/second;

Ascertained at baseline;

Defined as trouble with ≥1 ADL or IADL;

Defined from pharmacy data as having a fill within the prior 30 days

Overall, there were 408 (9.2%) participants with a history of PPI exposure at baseline, with 218 (53.4%) light users (defined as 31-540 SDD), 62 (15.2%) moderate users (defined as 541-1080 SDD), and 128 (31.4%) heavy users (defined as ≥ 1081 SDD). As of end of study follow-up, there were 1,061 (23.9%) exposed participants with 488 (46.0%) light users, 155 (14.6%) moderate users, and 418 (39.4%) heavy users. Examining results based on follow-up time, there were 22,852 person-years during which participants had <=30 SDD (reference group), 2,144 person-years during which participants had light use, 697 person-years during which participants had moderate use, and 1,530 person-years during which participants had heavy use. Compared to those contributing person-time to the reference group, person-years accumulated during periods of light, moderate, or heavy levels of PPI exposure were associated with greater comorbidity, adverse health characteristics, and higher levels of concomitant medication use (Table 2). Among the 4,438 study participants, 21 (0.7%) reported OTC use of PPIs at some point during ACT follow-up, 19 at a single ACT follow-up visit and 2 at 2 ACT visits. Because OTC use was so rare, we did not attempt to incorporate this information into our categorization of cumulative exposure.

Over a mean follow-up of 6.1 years, 802 participants (18.1%) experienced a fracture of the hip, forearm, humerus, clavicle or scapula, rib or sternum, tibula or fibula, or ankle. The most common fracture type was hip fracture, comprising 23% of all observed events, followed by fractures of the forearm (22%), rib and sternum (18%), humerus (13%), ankle (9%), pelvis (6%) tibia and fibula (6%), and clavicle and scapula (3%). No overall association was found between the categories of cumulative PPI exposure and risk of fracture in this population. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) comparing various groups to the reference group was 1.08 (95% CI 0.83-1.40) for light users, 1.31 (95% CI 0.86-1.95) for moderate users, and 0.95 (95% CI 0.68-1.34) for heavy users (Table 3). Results from the fully adjusted model are available in supplementary material (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3.

Risk of fractures associated with PPI exposure†

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cumulative use, SDDs | Follow-up time (person-years) | Number of Events | Incidence (per 1000 person-years) | Age and sex - adjusted | Fully adjusted‡ |

| No use, ≤30 | 22,852 | 641 | 28.1 | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Light use, 31-540 | 2,144 | 78 | 36.3 | 1.19 (0.93-1.51) | 1.08 (0.83-1.40) |

| Moderate use, 541-1080 | 697 | 30 | 43.0 | 1.50 (1.04-2.18) | 1.31 (0.86-1.95) |

| Heavy use, ≥1081 | 1,530 | 53 | 34.6 | 1.17 (0.87-1.56) | 0.95 (0.68-1.34) |

|

| |||||

| Recent users* | 1.29 (1.06-1.56) | 1.14 (0.91-1.42) | |||

adjusted for age, sex, epilepsy, treated diabetes, treated hypertension, depression, impaired cognition, vision problems, stroke, CHF, CAD, low gait speed, difficulty with ADLs, difficulty with IADLs, exercise, BMI, smoking, self-rated health, Charlson comorbidity index, fracture in past 5 years, and use of prescription opioids, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, NSAIDs, antidepressants, thiazide diuretics, bisphosphonates, corticosteroids, H2RAs and HRT.

restricted to PPI users only and compares those with recent use (use within prior year) to the reference group of distant users

There was no evidence of an association between PPI use and fracture in subgroups defined by age (> 75 years compared to ≤75 years) or sex with p-values of 0.09 and 0.46, for the difference in relative risks by age and sex, respectively (data not shown). In the recency analysis, we found no evidence of differing fracture risk between these groups, with an aHR of 1.14 (95% CI 0.91-1.42) characterizing the risk of fracture for those with recent exposure within the past year to those with distant use. Furthermore, no interaction was found between recency and cumulative exposure (p=0.25). We also found no evidence of a difference of risk in our current use analysis, which examined the risk of fracture among those having a fill for a PPI medication within the past 30 days compared to those without [aHR= 1.28 (95%CI 0.95-1.74)]

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of people aged 65 and older, we observed no association between PPI use and risk of non-vertebral fracture, with adjusted HRs of 1.08 (95% CI 0.83–1.40), 1.30 (95% CI 0.86–1.95), and 0.95 (95% CI 0.68–1.34) for those with light, moderate, or heavy use, respectively. The null finding for all exposure levels, particularly among the heaviest users, provides strong evidence that PPIs are not as dangerous with regard to non-spine vertebral fracture risk as other studies have found. Our finding of no increased risk of fracture associated with PPI use was robust to secondary analyses examining recency of use.

Prior studies have provided a range of estimates for the PPI-fracture association among older adults, with several studies reporting relative risks in the range of 1.4–2.5,2, 15, 28,29 results that are clearly inconsistent with our findings. The most rigorous studies to date of the question include one by Yu et al. in 20087 and a second by Gray et al. in 2010.8 Both conducted large cohort studies with well-controlled analyses. These studies had more nuanced findings, with positive associations seen for some fracture types but not others, and considerably lower risk estimates when positive findings were seen. In brief, the study by Yu et al. considered a population aged 65+ and found no association between PPI use and hip fracture (RR 1.16, 95% CI: 0.8–1.67) but did find an association between PPI use and non-spine fracture (RR 1.34, 95% CI: 1.10–1.64). Yu et al. examined a binary exposure, making it difficult to compare their findings directly to ours which looked at multiple exposure levels. The study by Gray et al. used a modestly younger and entirely female population (aged 50–79 years) from the Women’s Health Initiative, and again observed no association between binary PPI use and hip fracture (HR 1.00, 95% CI: 0.71–1.40). However, associations were seen for fractures of any site or fractures of the spine with HRs of 1.25 (95% CI: 1.15–1.36) and 1.47 (95% CI: 1.18–1.82), respectively. Gray et al. also considered duration based on women bringing medication bottles to periodic follow-up visits, but lacked information on dose, which prevented them from assessing the relationship between fracture risk and cumulative dose. Surprisingly, they observed an increase in fracture risk for women with <1 year of use, but none for women with use of 1-3 or 3+ years duration. This finding does not seem biologically plausible based on the previously proposed mechanism of action between PPI use and fracture risk and is difficult to rationalize.

A possible explanation for the contradictory findings among the various studies is differences in how use of PPIs was classified and ascertained. Some studies categorized PPI use using a binary variable, while we attempted to improve on prior work by creating three categories of cumulative use to allow for assessment of a possible dose-response relationship. Furthermore, some prior studies relied on self-reported use, while others had access to computerized pharmacy data. The latter is likely to have greater validity.30 Another possible explanation could be differences in the ability to control for potential confounding factors, including concomitant medication use, physical activity, smoking, BMI, ADLs or IADLs, gait speed, and exercise (all of which the present study was able to consider).

Our study has limitations, including the possibility that residual confounding may have biased the results. For instance, information about alcohol use, which has been previously shown to be associated with fracture risk, was lacking.31 Additionally, diagnosis codes were used to ascertain fractures, so misclassification of outcome status could have biased results. This would likely have been non-differential and could have biased results toward the null. Attempts were made to reduce misclassification by defining outcomes using codes previously shown to have high PPV in KPWA data.

In conclusion, in contrast to some prior studies, we observed no appreciable association of PPI use with risk of fracture. The null finding for all exposure levels provides strong evidence that these medications are not as dangerous with regard to non-vertebral fracture risk as other studies have found. Furthermore, results for the heavy use group had an upper CI bound of 1.34, meaning that the greatest levels of cumulative use are not consistent with a risk greater than 34%. At this time, we believe it is not appropriate to include an increased fracture risk as a downside to the use of PPIs.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Previous studies have inconsistently reported an increase in fracture risk among users of proton pump inhibitors

Fractures are a critically important outcome among older adults because of their association with declining health

Proton pump inhibitors are widely used medications with approximately a third of the adult population using these medications

This study found no association of fractures with proton pump inhibitor use among those with light, moderate, or heavy use defined using standard daily dose categories, and there was no evidence of a dose-response relationship.

Acknowledgments

The data were provided by the Adult Changes in Thought study at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute whose staff members handle subject recruitment, data collection and data management. The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, analysis or preparation of the paper. Financial support was not received for this work.

Funding/Support

The Adult Changes in Thought study is funded by the National Institute of Health grant 5U01AG006781‐29, Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Registry (ADPR/ACT).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the contributing authors have any financial, personal or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ali T, Roberts DN, Tierney WM. Long-term safety concerns with proton pump inhibitors. The Am J Med. 2009;122:896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis JR, Barre D, Zhu K, et al. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and falls and fractures in elderly women: a prospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:2489–2497. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalili H, Huang ES, Jacobson BC, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of hip fracture in relation to dietary and lifestyle factors: a prospective cohort study. Bmj. 2012;344:e372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker M, Johansen A. Hip fracture. Bmj. 2006;333:27–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7557.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks R. Hip fracture epidemiological trends, outcomes, and risk factors, 1970–2009. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3:1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colon-Emeric CS, Saag KG. Osteoporotic fractures in older adults. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu EW, Blackwell T, Ensrud KE, et al. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of bone loss and fracture in older adults. Calcif Tissue Intl. 2008;83:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9170-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray SL, LaCroix AZ, Larson J, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use, hip fracture, and change in bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:765–771. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiu HF, Huang YW, Chang CC, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors increased the risk of hip fracture: a population-based case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:1131–1136. doi: 10.1002/pds.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge CJ, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179:319–326. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser LA, Leslie WD, Targownik LE, et al. The effect of proton pump inhibitors on fracture risk: report from the Canadian Multicenter Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Intl. 2013;24:1161–1168. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaye JA, Jick H. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of hip fractures in patients without major risk factors. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:951–959. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.8.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corley DA, Kubo A, Zhao W, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2 receptor antagonists are associated with hip fractures among at-risk patients. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:93–101. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Proton pump inhibitors, histamine H2 receptor antagonists, and other antacid medications and the risk of fracture. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;79:76–83. doi: 10.1007/s00223-006-0021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, et al. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006;296:2947–2953. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grigoryan M, et al. Recognizing and reporting osteoporotic vertebral fractures. European Spine Journal. 2003;12(Suppl 2):S104–S112. doi: 10.1007/s00586-003-0613-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1737–1746. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders KWDR, Stergachis A. Group Health Cooperative. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. ATC/DDD system. 2009;2016 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovstadius B, Petersson G. Non-adherence to drug therapy and drug acquisition costs in a national population - a patient-based register study. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11:326. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hungin AP, et al. Systematic review: Patterns of proton pump inhibitor use and adherence in gastroesophophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(2):109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackey DC, et al. High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2381–2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KM, et al. Ankle fractures have features of an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporosis Int. 2013;24(11):2819–25. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6:45–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001602. discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buttery AK, Busch MA, Gaertner B, et al. Prevalence and correlates of frailty among older adults: findings from the German health interview and examination survey. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:22. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0022-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moberg LM, Nilsson PM, Samsioe G, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and history of earlier fracture are independent risk factors for fracture in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2014;78:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roux C, Briot K, Gossec L, et al. Increase in vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women using omeprazole. Calcif Tissue Int. 2009;84:13–19. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hafferty JD, Campbell AI, Navrady LB, et al. Self-reported medication use validated through record linkage to national prescribing data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;147(8):084905. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berg KM, Kunins HV, Jackson JL, et al. Association between alcohol consumption and both osteoporotic fracture and bone density. Am J Med. 2008;121:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.