Abstract

Nanoparticle-based therapeutic, prevention, and detection modalities have the potential to greatly impact how diseases are diagnosed and managed in the clinic. With the wide range of different nanomaterials available to nanomedicine researchers, the rational design of nanocarriers on an application-specific basis has become increasingly commonplace. In this review, we provide a comprehensive overview on an emerging platform: cell membrane coating nanotechnology. As one of the most fundamental units in biology, a cell carries out a wide range of functions, including its remarkable ability to interface and interact with its surrounding environment. Instead of attempting to replicate such functions via synthetic techniques, researchers are now directly leveraging naturally derived cell membranes as a means of bestowing nanoparticles with enhanced biointerfacing capabilities. This top-down technique is facile, highly generalizable, and has the potential to greatly augment the potency and safety of existing nanocarriers. Further, the introduction of a natural membrane substrate onto the surface of a nanoparticle has enabled additional applications beyond those already associated with the field of nanomedicine. Despite the relative youth of the cell membrane coating technique, there exists an impressive body of literature on the topic, which will be covered in detail in this review. Overall, there is still significant room for development, as researchers continue to refine existing workflows while finding new and exciting applications that can take advantage of this emerging technology.

Keywords: biomimetic nanomedicine, drug delivery, medical imaging, immunotherapy, detoxification

Table of content entry

Cell membrane coating is an emerging nanotechnology. By cloaking nanomaterials in a layer of natural cell membrane, which can be derived from a variety of cell types, it is possible to fabricate nanoplatforms with enhanced surface functionality. This can lead to increased nanoparticle performance in complex biological environments, which can benefit applications like drug delivery, imaging, phototherapies, immunotherapies, and detoxification.

1. Introduction

Nanotechnology-based solutions, nanoparticles in particular, have become increasingly prevalent in medical research, as they can offer significant advantages in both efficacy and safety when compared with current therapeutic and diagnostic modalities.[1–5] From a reductionist perspective, the design of a nanoparticle formulation can generally be divided into two segments. The first is incorporation of a payload that carries out an application-specific function, such as the killing of cancer cells or providing imaging contrast. The second, which we focus on in this review, is providing the loaded nanoparticle with an effective means of interacting with its environment, both by decreasing nonspecific interactions while increasing specific targeting. Regardless of how promising an experimental compound or material is in vitro, efficient biointerfacing is a prerequisite for successful translation in vivo.[6] Once administered into the body, a nanoparticle encounters a highly complex environment that is inherently adept at recognizing and eliminating foreign elements. For example, in the bloodstream there are various protein-based and cellular constituents; contact with any of these can quickly compromise performance.[7,8] Uptake by the reticuloendothelial system before a nanoparticle can reach its target is one of the major hurdles that almost all platforms must overcome.[9,10] Along with reducing nonspecific nanoparticle uptake, the addition of specific targeting mechanisms can help to further boost efficacy by promoting preferential accumulation at a site of interest.[11,12] Ultimately, the goal is to engineer nanoparticles with surfaces that enable them to be ignored by everything except for their target, a task that has proven to be exceptionally difficult.

Given the importance of nanoparticle biointerfacing, the purposeful engineering of their surfaces is now understood to be a critical aspect in the overall design process. Traditionally, the gold-standard has been to introduce the synthetic polymer polyethylene glycol (PEG) onto the particle surface.[13,14] PEGylation creates a hydration layer, while also providing steric stabilization. The end result is a stealthy nanoparticle surface that interacts less with its environment, enabling significantly enhanced blood circulation. To add targeting functionality, a wide range ligands, including antibodies, aptamers, peptides, and small molecules, can be further included.[15] While synthetic strategies for prolonging circulation and adding targeting functionality have demonstrated incredible utility for enhancing nanodelivery platforms, there is still significant room for improvement. PEG has proven effective at minimizing nonspecific interactions in complex media, but there are increasing reports of immune responses against the synthetic polymer, and the presence of antibodies against PEG can potentially impact performance over multiple administrations.[16,17] Additionally, bottom-up targeting ligand conjugation strategies become increasingly difficult, especially for large-scale manufacturing, as more surface functionalities are required.

Due to the challenges facing synthetic nanoparticle functionalization strategies, there have recently been considerable efforts dedicated towards bioinspired nanotechnology, where design cues for effective design are taken from nature.[18–21] This can take many forms, such as the mimicry of physical properties, including shape and flexibility,[22] and the direct leveraging of naturally derived materials.[21] Considering the inherently biological nature of nanoparticle interactions in vivo, biomimicry is a rational approach towards effective nanoparticle designs, as it leverages naturally occurring strategies that have been refined by the process of evolution. Consider the cell, one of the most fundamental units of biology, which is particularly adept at carrying out defined functions within complex environments. Either independently or as part of a multicellular organism, a cell comes into contact with a wide range of proteins, other cells, and extracellular matrices, but elegantly manages to carry out the specific tasks necessary for its survival. By employing biomimetic design principles, researchers hope to capture the incredible sensitivity and specificity that are inherent in nature.

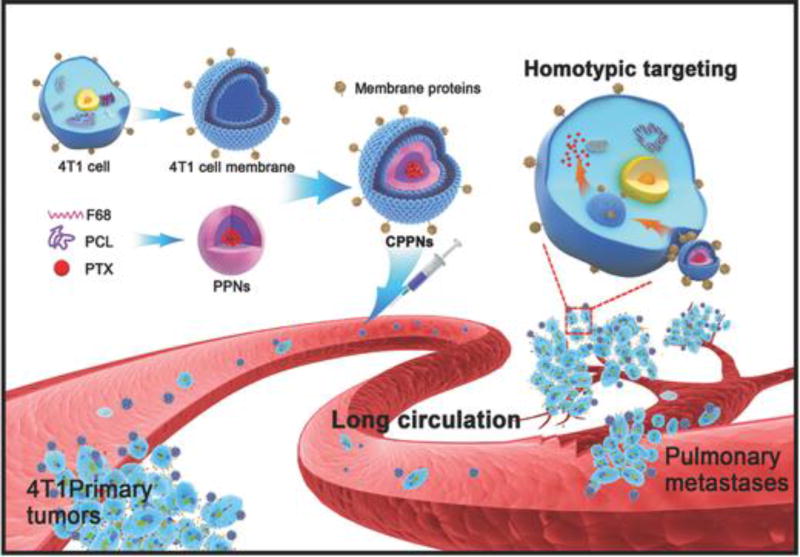

Spawning from this movement is a new class of biomimetic nanoparticles that combine the advantages of both natural and artificial nanomaterials.[23–26] Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles are characterized by a synthetic nanoparticulate core cloaked by a layer of natural cell membrane (Figure 1). Cell membrane coating is a platform technology that presents a facile top-down method for designing nanocarriers with surfaces that directly replicate the highly complex functionalities necessary for effective biointerfacing. Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles inherently mimic the properties of the source cells from which the membrane is derived, bestowing a wide range of functions such as long circulation and disease-relevant targeting.[23,24] In this review, we provide a comprehensive overview of this new technology, from its initial development to the current state of the art. A specific emphasis is placed on the different types of membrane coatings currently employed, along with their special features. Their advantages for specific applications are covered in depth, including some applications that uniquely benefit from the presence of biological membranes. The utility of the cell membrane coating approach will undoubtedly expand as time progresses, and we conclude with discussion on potential future directions.

Figure 1.

Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles. A variety of cell types have been used as sources of membranes to coat over nanoparticles. Each cell membrane type can utilize unique properties to provide functionalities to nanoparticulate cores, the material of which can be varied depending on the desired application.

2. Development of Cell Membrane Coating Technology

Synthetic functionalization strategies have been successfully employed to greatly enhance nanoparticle performance for a wide range of different applications. In many cases, they do an excellent job of replicating individual biological interactions found in nature. However, as researchers continue to push the boundaries of nanomedicine, bottom-up fabrication strategies become increasingly difficult to replicate the collective functions of biological systems because in reality they are incredibly complex and multifactorial. Additionally, synthetic platforms must also overcome the fundamental fact that they are, by their very nature, foreign. As such, researchers have recently turned towards biomimicry as a guiding principle for the design of next generation nanoplatforms.[18–20,27,28] By leveraging the mechanisms and interactions crafted by nature over the course of millions of years of evolution, significant steps have been made towards further improving nanoparticle functionality while streamlining development.

2.1 Background

The cell is one of the most fundamental units of life, and it must perform a variety of complex functions in order to survive and proliferate. To do such, cells must interact with their surrounding environments, and it is their outermost layer, consisting of cell membrane, that bears the bulk of this responsibility. Cell membrane is composed of a mixture of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates. Lipids are largely responsible for the bilayer structure and fluidity of the membrane, while also playing a role in signaling. Proteins, either transmembrane or membrane-anchored, and carbohydrates are responsible for providing the interfacing functionalities of the membrane. For example, carbohydrate chains terminated in specific sugar residues demonstrate important roles in cellular recognition.[29,30] Proteins play major roles in signaling and adhesion;[31,32] the expression profile of surface protein markers determines important characteristics about individual cell types, including where they localize,[33] how they respond to environmental cues,[34] and how they exert influences on other cells.[35] While knowledge is still accumulating on the role of individual protein markers, at least some information is available regarding the function of many. Notable examples, like the “self-marker” CD47, have significant implications for the design of biomimetic nanocarriers.[36] Adhesion and binding molecules present on specific cell subsets also have the potential for guiding the design of platforms that exhibit organotropism.[37] Researchers have used surface glycan-mimicking molecules to improve colloidal stability or to increase targeting specificity, particularly towards immune cell subsets.[38,39] Proteins or their derivatives, including those such as the minimal “self-peptide” derived from CD47,[40] can be directly conjugated onto nanoparticles surfaces. Taking advantage of such native functionalities originating from the cell membranes has become a topic of significant interest. While biomimetic design strategies exist in many different forms, from mimicking the physical properties of cells to the identification of natural targeting ligands,[18,22] one of the most appealing approaches is the direct use of cellular membrane components for nanoparticle functionalization.[21]

2.2 Initial concept of cell membrane coating technology

In 2011, the cell membrane coating technology was first reported, in which researchers directly leveraged entire cell membranes as a material for nanoparticle coating.[23] By transferring the outermost layer of a cell directly onto the surface of a nanoparticle, the complexity of the membrane, with all of its lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates, can be faithfully preserved, enabling the resultant membrane-coated nanoparticle to take on many of the properties exhibited by the source cell. This concept was first demonstrated using red blood cells (RBCs) as the source of membrane material (Figure 2).[23] RBCs, which are responsible for oxygen delivery within the body, are known to have a lifespan of up to 4 months in humans. The ability of these cells to circulate for extended periods of time, a highly desirable property for nanoparticle drug delivery, is mediated by RBC surface markers, including CD47 and an array of complement regulatory proteins.[27,36] In the initial proof-of-concept study, membrane ghosts were first obtained via the hypotonic lysing of the RBCs, and the membrane was fashioned into vesicles via a combination of sonication and mechanical extrusion through porous membranes. When subsequently co-extruded with preformed polymeric cores made from poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), the resultant nanoparticles exhibited a core-shell structure when viewed under transmission electron microscopy (TEM), with the membrane surrounding the core. Size and zeta potential measurements were also consistent with a layer of membrane coating around the cores. Notably, the nanoparticles were able to circulate for extended periods of time when administered intravenously in a mouse model, with an elimination half-life of approximately 40 hours, outperforming a PEGylated control. This long circulation property was attributed to the natural RBC membrane and highlighted the potential of cell membrane coatings for nanoparticle functionalization.

Figure 2.

RBC membrane-coated nanoparticles. Cell membrane can be derived from RBCs using hypotonic treatment. When co-extruded with polymeric nanoparticulate cores, RBC membrane-coated nanoparticles are formed. The nanoparticles retain many of the same surface markers as the original RBCs, including the self-marker CD47 that allows for immune evasion and long blood circulation. Reproduced with permission.[23] Copyright 2011, National Academy of Sciences.

2.3 Characteristic analyses

Further studies on RBC membrane-coated nanoparticles (RBC-NPs) have helped to provide a greater understanding of their unique properties. For example, it was confirmed that the membrane functionalization process successfully translocated the self-marker CD47, which was present at a density consistent with the source RBCs.[41] Further, gold immunostaining was employed to demonstrate that the protein was incorporated in a right-side-out orientation, which is essential for its proper functioning. This allows CD47 to correctly interface with its corresponding receptor, thus lowering macrophage uptake. Glycoprotein and sialic acid assays also demonstrated that carbohydrate residues from the cell membrane were found almost exclusively on the outer face of the nanoparticles, again consistent with a right-side-out coating.[42] The importance of surface proteins and carbohydrates for nanoparticle stability was also highlighted, as removal via trypsinization destabilized RBC-NPs at physiologically relevant salt concentrations. Another independent study using a dye quenching system also arrived at the conclusion that a majority of the membrane on RBC-NPs exists in a right-side-out orientation.[43] In another study, biotinylated PLGA cores were used to demonstrate the completeness of membrane coatings; at sufficient ratios of membrane to polymer, streptavidin-induced crosslinking of the biotinylated PLGA cores could be entirely prevented.[42] Due to the charge asymmetry inherent to biological membranes, it has been demonstrated that a negative nanoparticle surface best facilitates membrane coating, whereas positively nanoparticle substrates interact strongly with the membranes, leading to a crosslinked network. Finally, nanoparticles of varying sizes, ranging from tens of nanometers to several hundred nanoparticles, have been successfully coated with cell membrane.[42]

Following the initial reports on RBC-NPs, the strategy of using cell membranes to functionalize nanoparticle surfaces has since been shown to be highly generalizable, expanding to cover a wide range of different nanomaterials combined with membranes derived from various cells types. Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles have also been incorporated into other formats, such as into hydrogels,[44] or can be fabricated via templated synthesis schemes in which the nanoparticulate core is formed in situ.[45] All of these variations, along with their applications, will be covered in depth in subsequent sections.

2.4 Methods of coating

Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles can be fabricated using several different methods. Initial works relied exclusively on physical extrusion in which nanoparticulate cores and purified membrane are co-extruded through a porous membrane.[23] This method was adapted from the synthesis of synthetic liposomes, and the mechanical force provided by the extrusion is believed to disrupt the membrane structure and enable it to reform around the nanoparticulate cores. More recently, a sonication-based approach has been employed.[46] Using this technique, the two components are subjected to disruptive forces provided by ultrasonic energy, resulting in the spontaneous formation of a core-shell nanostructure. Results from this method are consistent with those of particles made using physical extrusion, with the added benefit of less material loss. In terms of the mechanism responsible for membrane coating, it is believed that a combination of the semi-stable nature of bare nanoparticulate cores and cell membrane-derived vesicles, along with the charge asymmetry of biological membranes, makes the core-shell configuration with right-side-out membrane orientation energetically favorable.

Other novel methods for the encapsulation of nanoparticulates into cell membranes have been reported. Very recently, a microfluidic system that combines rapid mixing with electroporation has been employed to successfully coat RBC membrane around magnetic nanoparticles.[47] The reported device consisted of a Y-shaped merging channel, S-shaped mixing channel, and an electroporation zone right before the outlet. By fine-tuning the pulse voltage and duration, as well as the flow velocity, high-quality particles with complete coatings and exceptional stability were fabricated. Beyond techniques that use purified membrane material, there is a unique approach based on the in situ packaging of nanomaterials using live cells.[48] In this fabrication scheme, cells were first incubated with iron-oxide nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, or quantum dots. It was then demonstrated that, when incubated in serum-free media, the cells could secrete vesicles containing the exogenous nanoparticles.

3. RBC Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles

RBCs are nature’s long circulating carriers. These cells live up to 120 days in humans, enabling them to fulfill their important biological function of transporting oxygen. With limited immune cell clearance, RBC membrane was an attractive first choice for cell membrane coating onto nanoparticles. The RBC-NP became the first cell membrane-coated system reported, and it is currently the most well-studied in the field. The rapid expansion of this platform is partially due to the ease of cell collection and lack of intracellular organelles, which make membrane collection simple and scalable for efficient manufacturing. In addition, RBC-NPs have the clearest path towards translation, as blood transfusions are common, and there is the potential to use type-matched RBCs as membrane sources to maximize biocompatibility for wide clinical use.

3.1 Drug delivery

Drug delivery is traditionally one of the staples of nanomedicine, and thus there has been a significant amount of research applying RBC-NPs for a variety of drug delivery applications. In one of the first examples, doxorubicin (DOX) was loaded into poly(lactic acid) PLA cores and subsequently coated with RBC membrane.[49] Two different methods of drug loading, physical encapsulation and chemical conjugation, were assessed for encapsulation efficiency and drug release kinetics. Physical encapsulation of DOX was achieved by mixing the drug with PLA polymer in the organic phase, follow by nanoprecipitation into an aqueous phase. In the chemical conjugation method, ring-opening polymerization was used to make a DOX-PLA polymer conjugate, which was then directly precipitated into an aqueous phase to form nanoparticles. It was demonstrated that the chemical conjugation of DOX to the PLA enabled higher drug loading and provided a more sustained release over time. Additionally, the layer of membrane coating served as a diffusional barrier that further slowed drug release kinetics. When incubated with Kasumi-1 leukemia cells, both drug-loaded nanoformulations demonstrated increased cytotoxicity compared with free drug, which is likely due to their ability to overcome the drug-efflux mechanisms present in the cells. A similar DOX-loaded RBC-NP formulation was used to treat a murine model of lymphoma, demonstrating a marked ability to increase survival compared with equivalent doses of free drug.[50] It was further shown that the RBC-NP nanocarriers themselves were generally safe and did not display any myelosuppression effect, whereas free drug caused an obvious reduction in multiple immune cell subsets. In addition, no anti-RBC antibodies were detected in mouse serum even after multiple RBC-NP administrations, indicating no acute or long-term immune responses against the nanoparticles. The safety and long-term applicability of using RBC membrane coatings was also demonstrated using an iron oxide nanoparticle platform.[51] In the study, it was demonstrated that RBC membrane coating significantly outperformed PEG in terms of enhancing circulation. As previously shown, upon repeat administration, PEGylated nanoparticles had increasingly short circulation times due to the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon, which is orchestrated by anti-PEG IgM and IgG antibodies that form after each injection. The RBC-NPs, however, did not cause an increase in IgM or IgG antibodies after multiple injections, and thus the long circulation time of the particles was consistent over multiple injections. In addition to avoiding the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon, RBC-NP administration caused no overt signs of toxicity and the level of myeloid-derived suppressor cells were consistent with baseline values. Taken together, these studies indicate that RBC membrane coating may serve as a viable alternative to PEG that can be used without fear of immunogenicity.

Despite the fact that a major advantage of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles is the ability to transfer over native functionalities via associated surface markers, several strategies have been developed to add further membrane surface functionality. Typical functionalization techniques rely on chemical conjugation, such as sulfhydryl-, carboxyl-, and amine-based reactions. However, when working with biological membranes, one challenge is that components such as proteins are prone to denaturation compared to purely synthetic nanoparticles. To preserve the membrane’s biological activity, alternatives to chemical conjugation need to be considered, and so far, several non-disruptive functionalization techniques have been developed to address this potential issue. One strategy has been to use a lipid-tethering technique to introduce additional ligands onto RBC-NP surfaces.[52] In the study, different molecules, such as the small molecule folate or the aptamer AS1411, were attached via a linker to a lipid anchor. The product could then be inserted into RBC membrane, which was subsequently used to prepare targeted RBC-NPs. Using the targeted versions of the nanoparticles, it was demonstrated that uptake to cells overexpressing the corresponding receptors could be significantly enhanced. In a separate example, maleimide-terminal PEG linkers were attached to the RBC membrane via a succinimidyl ester, enabling surface decoration with thiolated enzymes.[53] Using a thiolated recombinant hyaluronidase as a model enzyme, nanoparticles capable of more efficiently diffusing through the hyaluronic acid-rich extracellular matrices of tumors were fabricated. In a similar fashion, streptavidin can be inserted into the RBC membrane to allow for binding of extrinsic ligands modified with biotin. This two-step functionalization method was used to modify RBC-NPs with a positively charged candoxin-derived peptide, providing the nanoparticles with brain endothelial cell targeting abilities.[54] When loaded with DOX, these brain-targeting nanoparticles could more effectively treat mouse gliomas compared to the unmodified RBC-NPs. Beyond physical conjugation, other strategies such as co-administration with tumor-penetrating peptide iRGD have been used to further boost the natural tumor accumulation of RBC-NPs.[55] Paclitaxel (PTX)-loaded RBC-NPs injected in combination with the peptide showed increased drug delivery to tumors and sites of metastasis, and treatment with the nanoparticles could inhibit tumor growth in a 4T1 mouse tumor model.

To directly navigate nanoparticles to a desired location, RBC membrane can be coated over cores with a magnetic component for guided delivery. In the first example of such a system, the chemotherapeutics PTX and DOX were encapsulated along with iron oxide nanocrystals in O-carboxymethyl-chitosan nanoparticles via a double emulsion process.[56] The membrane coating significantly attenuated cellular uptake compared to a PEGylated version of the nanoformulation. After further functionalizing with RGD on the surface using a lipid-insertion approach, the targeted formulation was effectively internalized by Lewis lung carcinoma cells, an effect that was further facilitated by application of magnetic field. Using a mouse model with the same cells, the membrane-coated nanoformulation with the RGD targeting ligand very efficiently localized to the tumor in the presence of a magnetic field. Due to the improved localization to the tumor site, as well as the expedited cellular uptake, the drug-loaded nanoparticles were able to significantly control tumor growth while prolonging survival. Safety studies showed the membrane-coated formulation did not elevate serum antibody levels, whereas administration of the clinically used Taxol formulation resulted in spikes of IgE levels. Further, the membrane-coated formulation did not have leuko-depletive effects compared with Taxol.

Beyond standard encapsulation and delivery of chemotherapeutics, more sophisticated strategies for triggered release have demonstrated compatibility with the RBC membrane coating approach. In the first such example, a near infrared (NIR)-triggered formulation was made by incorporating a thermosensitive lipid into the nanoparticle core material.[57] In the system, the chemotherapeutic PTX was incorporated into polycaprolactone (PCL) cores coated with 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), which has a melting transition temperature of 41.5 °C. An outer RBC membrane layer included a lipophilic dye 1,1-dioctadecyl-3,3,3,3-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide (DiR), which can induce hyperthermia upon excitation. It was demonstrated that, upon laser excitation, the release of drug was facilitated as the core lost structural integrity. Combined with an increase in cell permeability during laser excitation, PTX was rapidly delivered intracellularly, enhancing cytotoxicity of the nanoformulation. Using a 4T1 mouse breast cancer model, it was shown that the nanoformulation could much more effectively localize to the tumor compared with free DiR, and this enabled a significant rise in temperature when the tumor was excited with NIR light. This ultimately translated to improved tumor control and reduction in the number of lung metastases when mice were treated with the thermally sensitive nanoparticle. In a similar system, DOX and the photosensitizer chlorin e6 (Ce6) were loaded into mesoporous silica nanoparticles and coated with RBC membrane.[58] The membrane coating helped to trap the drug within the mesoporous structure until far-red laser irradiation, during which the Ce6 generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) and disrupted the membrane structure, triggering drug release. Similarly, the Ce6- and DOX-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles were able to deliver the DOX to tumor sites in a responsive manner, leading to a control of tumor growth and metastasis formation in a 4T1 mouse tumor model. Using this system, it was also demonstrated that intracellular ROS production after nanoparticle uptake positively correlated with the laser power, indicating that the same Ce6-generated ROS that triggered drug release could continue to act as a photodynamic therapy, combining with the chemotherapy to improve tumor cell destruction. In another example, a layer of TiO2 was coated around docetaxel (DTX)-encapsulated SiO2 nanoparticles, and subsequently coated with RBC membrane.[59] The TiO2 enabled the photocatalytic degradation of the membrane coating upon ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, facilitating drug release. Similar to the Ce6 photosensitizer, the TiO2 is able to generate ROS that can degrade the membrane coating as well as act directly as a photodynamic therapy to improve cytotoxicity to cancer cells. In some cases, the drug delivery vehicle can also act as the photosensitizer. A very recent example used hollow mesoporous nanoparticles made of Prussian blue, a material that is inherently adept at photothermal conversion, to load DOX at extremely high weight ratios.[60] Coating the particles with a layer of RBC membrane helped to stabilize the nanoparticles over time and improved their safety profile. The longer circulation time provided by the RBC membrane layer allowed for improved localization to the tumor site, and when combined with NIR laser irradiation, the triggered drug release resulted in significant control of tumor growth.

In contrast to externally triggered release, RBC-NPs have also been modified to release payloads in response to natural environmental changes around tumor sites, such as increased local acidity. For example, a PTX-polymer prodrug made using pH-sensitive poly(L-γ-glutamylcarbocistein) (PGSC) was self-assembled into nanoparticles and wrapped in RBC membrane.[61] When incubated at a pH of 6.5, PTX release was faster than when incubated at a normal body pH of 7.4. Wrapping in RBC membrane significantly reduced uptake into macrophages, helping the particles to evade the immune system and circulate long enough to reach the acidic tumor microenvironment, where the PTX was triggered to release and exert an antitumor effect. Antitumor efficacy has also been achieved with a pH-responsive nanogel delivering a chemotherapy and cytokine combination.[62] Oppositely charged chitosan derivatives and a crosslinker were used to encapsulate PTX and interleukin (IL)-2, a T cell-supporting cytokine, into a nanogel formulation. RBC membrane was then extruded around the nanogel to facilitate membrane coating, which was used to protect the payload while allowing for long circulation and passive accumulation to the tumor site. Once in a weakly acidic tumor microenvironment, the negatively charged amphoteric chitosan derivative protonates and becomes positively charged, and electrostatic repulsion causes disintegration of the core and release of the chemotherapy and cytokine. With this strategy, the RBC-NPs had increased release of PTX and IL-2 at pH 6.5 compared to pH 7.4, an extended blood circulation time, and at least a fivefold increase in tumor delivery of both cargos. Enhanced delivery of the chemo-immunotherapy and the tumor microenvironment pH-triggered release led to improved antitumor efficacy in an aggressive B16-F10 melanoma model. In a different example, drug-loaded and pH-responsive RBC-NPs were formulated by remote loading into RBC membrane-derived vesicles.[63] To accomplish this, additional cholesterol was supplemented to RBC vesicles to further stabilize the membrane structure and enable the retention of a pH gradient across the RBC membrane. Using this stable pH gradient, small molecule therapeutics such as DOX and vancomycin were able to be remotely loaded into the vesicle interiors until destabilization of the RBC membrane vesicles prompted drug release in acidic conditions. The improved delivery and drug release were shown to improve therapeutic efficacy of DOX in a 4T1 mouse breast cancer model, and it also significantly decreased methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) burden in a murine skin infection model.

While most examples of RBC membrane-coated nanodelivery systems have been for the delivery of chemotherapeutics to tumors, there is an emerging use of such technology for treatment of bacterial infection. Core-shell gelatin nanoparticles loaded with the antibiotic vancomycin were coated with RBC membrane to make a combinatorial platform featuring environmentally sensitive antibiotic delivery and detoxification.[64] Using this system, vancomycin could be loaded at approximately 11.4 wt% into the gelatin core, and the membrane coating minimized uptake by macrophages. An advantage of using a gelatin-based nanoparticle is that it can responsively disintegrate in the presence of gelatinase, which is secreted locally by a wide range of bacteria. As an added benefit, the particles attenuated hemolysis induced by the exotoxin-rich medium of various bacteria. In a separate example, vancomycin-loaded nanogels generated by in situ gelation within RBC vesicles also showed promise for intracellular antibacterial treatment.[65] The gel was fabricated using a disulfide-based crosslinker, which contributed redox-responsiveness to the system. The responsiveness was confirmed in the presence of a reducing agent, which significantly enhanced drug release. The same effect was not observed when a similar non-responsive nanogel was fabricated. The nanoparticle played multiple roles to aid in the clearance of bacteria. First, the RBC membrane neutralized pore-forming toxins secreted by bacteria, which better enabled phagocytic uptake by macrophages and decreased bacterial virulence. Further, due to the loaded drug and redox responsive core, the vancomycin was released once taken up into the reducing environment of infected cells, enabling the treatment of intracellular bacteria and lowering the burden of live bacteria within macrophages when compared with free drug.

It is sometimes desirable to deliver large payloads to the inside of a cell. Such is the case for some intrabodies, which are antibodies that target intracellular targets not found on cell surfaces. The membrane-coating strategy has been adapted to deliver these biomolecules; antibodies against the cytoplasmic tumor marker, human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), were formed into nanoparticle cores before being coated with RBC membrane.[66] The antibody cores were synthesized by resuspending lyophilized hTERT antibodies in hydrochloric acid and titrating with sodium hydroxide until the isoelectric point was reached and the antibodies spontaneously precipitated out into nanoparticles. The collected particles could then be extruded with RBC membrane to form coated nanoparticles approximately 200 nm in size. It was shown that both the coated and uncoated nanoparticulate forms of the antibodies facilitated uptake into cells and prolonged circulation, but the coated version largely outperformed the uncoated antibody nanoparticles. Regarding nonspecific uptake, the membrane coating also helped to reduce macrophage uptake. To test the activity of the particles, a telomerase activity assay was performed. It was shown that the membrane-coated particles performed the best, decreasing telomerase activity to near 50% of original levels. Finally, histological analysis of tumor sections collected after injection of the formulations showed the highest degree of localization for the membrane-coated formulation. Overall, this work demonstrated a promising approach to enabling targeting of intracellular therapeutic targets that are difficult to access by traditional antibody administration.

3.2 Imaging and photoactivatable therapy

Imaging and photo-based therapies are important aspects of nanomedicine, especially given the wide range of nanomaterials that have the potential excel at such applications. Like with nanoparticle-based drug delivery, it has been demonstrated that RBC membrane coating holds great utility when applied to these other areas of research. In a first proof-of-concept study, it was shown that gold nanoparticles, which have unique optical properties that are useful for detection and photothermal applications, could be successfully functionalized with membrane coatings.[67] The coating of membrane led to a slight increase in nanoparticle size due to the new core-shell structure, and stability was maintained in both phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) for at least three days. Using a thiolated dye, it was demonstrated that the nanoparticles with membrane coatings could preclude binding and subsequent quenching by the gold cores. Using large polystyrene nanoparticles coated with antibodies against the self-marker CD47, it was also demonstrated that the membrane was largely configured in a right-side-out orientation. Finally, the coating helped to significantly reduce uptake by macrophage cells, which could easily be visualized using brightfield microscopy. With these results, it was postulated that membrane coating could help to reduce the rate of in vivo clearance compared to uncoated gold nanoparticles.

Beyond metallic nanoparticles, inorganic nanoparticles are also commonly used. In one instance RBC membrane was coated around upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) for tumor imaging.[68] In the work, it was shown that membrane-coated UCNPs could inhibit the binding of a protein corona, whereas uncoated particles attracted a significant layer of proteins when exposed to human plasma, which also led to significant increases in size. The particles were further functionalized via a lipid anchor with folic acid, which was used to help the particles efficiently target folate receptor-overexpressing cancer cells in vitro. The coated particles also exhibited a better targeting effect compared with folate-functionalized bare UCNPs, leading to increased blood residence and enhanced tumor localization in an MCF-7 tumor xenograft model in nude mice. After administration, it was further demonstrated that mouse blood chemistry remained normal and there was no readily observable damage of major organs upon histological analysis.

It was later demonstrated that RBC membrane-functionalized gold nanocages could be used to photothermally ablate cells after intracellular uptake (Figure 3).[69] The membrane coating enabled significantly enhanced circulation within the blood compared to non-functionalized nanocages, which led to decreased liver distribution and enhanced tumor uptake. Using a murine 4T1 tumor model, the nanoparticles could be used to elevate temperatures from 35 °C to 47.1 °C at the tumor site upon a ten-minute irradiation with a NIR laser. The induced hyperthermia had a significant impact on tumor growth and greatly extended survival. A similar photothermal effect was also demonstrated with RBC membrane-coated iron oxide nanoclusters.[70] After demonstrating successful coating, it was shown that the particles could be used to kill cells in a photoactivatable manner. Enhanced circulation increased the local concentration of particles in MCF-7 breast cancer xenografts, leading to control of tumor growth when subject to five minutes of laser irradiation. As an added benefit, the platform doubled as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent for theranostic applications, with a darker and longer lasting signal observed in the tumor area compared to uncoated iron oxide clusters. Similar RBC membrane-coated iron oxide nanoparticles were also fabricated using a microfluidic electroporation method instead of extrusion.[47] Consistent with the particles made using the extrusion protocol, the electroporation coated particles demonstrated the ability to simultaneously image tumors via MRI and photothermally ablate tumors upon irradiation. Additionally, RBC membrane-coated nanoparticles have been made with components that can combine photothermal abilities with chemotherapy delivery as detailed in the previous section.[57–60] In these cases, the photothermal components can be used to simply trigger drug release or as part of a photoablation-chemotherapy combination treatment.

Figure 3.

RBC membrane-coated gold nanocages for photothermal therapy. RBC membrane coating allows gold nanocages to circulate longer in the bloodstream and accumulate in tumors efficiently. When irradiated with an NIR laser, the nanocage cores raise the local temperature, thus enabling control of tumor growth. Reproduced with permission.[69] Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society.

Other than the use of synthetic materials, nanoparticle platforms based on natural and organic compounds have been taken advantage of as photothermal agents. In one case, melanin nanoparticles were coated with RBC membrane for combination photothermal therapy and photoacoustic imaging.[71] Natural melanin nanoparticles were extracted from the ink sacs of cuttlefish, and the resulting particles were between 100–200 nm in size. It was confirmed that these natural melanin particles had high photothermal conversion efficiency, enabling them to raise the temperature of solution more efficiently than control melanin-like polydopamine nanoparticles. After coating with RBC membrane, the resulting particles retained the photothermal conversion capabilities of their uncoated counterparts and were stable for at least a week. Further, they showed no toxicity when incubated with cells until radiation was applied. In vivo, the circulation of the coated particles was significantly enhanced compared with uncoated melanin particles, and accumulation was preferentially increased within the tumor in A549 xenografts. After intravenous administration, it was shown that the coated particles could be used to generate photoacoustic contrast at the tumor site, and local application enabled a significant rise in temperature at the tumor site upon irradiation. Finally, when used to treat a tumor, the irradiated membrane-coated particle virtually eliminated tumor growth. In comparison, tumors treated with an uncoated formulation and irradiated with the same power of laser still grew.

In general, RBC membrane coating can improve the circulation time of photothermal nanoparticles, which causes improved localization to tumors via the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect and enhances photothermal therapy. In combination with RBC-NPs, there have been recent efforts to strengthen the EPR effect and further increase tumor accumulation by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Cyclopamine, a steroidal alkaloid, has been used to disrupt the thick extracellular matrix of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and improve blood permeability for gold RBC-NPs.[72] RBC membrane-coated gold nanorods were developed that provided a nearly 15-fold increase in blood retention compared to uncoated gold nanorods with no significant effect on photothermal conversion efficacy. At the same time, to combat the limited blood vessel availability and dense tissue of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, cyclopamine treatment of human Capan-2 xenografts was explored. Daily oral administration of cyclopamine over three weeks yielded 60% reduction in tumor fibronectin expression, doubling the number of functional blood vessels, and improved tumor perfusion as shown by ultrasound imaging of tumors after microbubble injection. This modulated tumor microenvironment allowed for an almost twofold increase in coated gold nanorod accumulation compared to the accumulation in untreated tumors. Combined with laser irradiation, mice treated with cyclopamine and the biomimetic nanorods caused significant regression of tumor growth, while treatment with the nanorods alone or the cyclopamine alone yielded negligible results. Enhanced localization of photothermal nanoparticles was also realized using an endothelin A (ETA) receptor antagonist BQ123 to selectively dilate tumor vasculature.[73] By occupying the ETA receptor, which is overexpressed in tumors, vasoconstriction can be selectively blocked and blood perfusion throughout the tumor can increase. Confirming this idea, intraperitoneal injection of BQ123 into nude mice bearing HCT116 human colon carcinoma tumors resulted in a rapid dilation of tumor vessels by about 25%, increasing blood oxygen saturation levels to that of the surrounding normal tissue. Fluorescent imaging of labeled polypyrrole RBC-NPs after injection into BQ123 treated tumors demonstrated a 1.37 times higher local concentration of particles at the tumor site compared to untreated tumors. Co-administration of the RBC-mimicking polypyrrole nanoparticles and BQ123 followed by NIR irradiation in tumor-bearing mice yielded the highest temperature in the focal range, and this significantly suppressed tumor growth compared to the RBC-NPs alone or a combination therapy using a PEGylated polypyrrole nanoparticle with NIR irradiation.

Unlike photothermal therapy, which depends on local heating to create hyperthermia, photodynamic therapy relies on photosensitizers to generate ROS upon laser irradiation as the mode of killing. For both strategies, however, increased local concentration of the active agent to the tumor site can greatly enhance efficacy. Cell membrane coating has thus been used to enhance photodynamic nanoplatforms in much the same way as those for photothermal therapy. For example, UCNPs coated with a layer of the photosensitizer merocyanine 540 were subsequently coated with a layer of RBC membrane.[74] Upon NIR irradiation, the energy emitted by the nanoparticles transferred to the photosensitizer, facilitating the production and release of singlet oxygen capable of killing cancer cells. Using a singlet oxygen detecting sensor 9,10-anthracenediylbis(methylene)dimalonic acid, it was determined that the membrane-coated particles could very effectively generate reactive oxygen molecules. Upon incubation with cells and irradiation, the particles could effectively kill cells in vitro. Particles could also be further functionalized via lipid anchoring of both folate and triphenylphosphonium (TPP), the latter of which was used to target mitochondria to maximize the effect of ROS, with little detrimental effect on the long circulation of the coated particles. The dual-targeted nanoparticles could efficiently localize to established murine B16 tumors using the folate receptors, and the TPP allowed internalized particles to bind to the mitochondria. Upon laser application, the resulting photodynamic therapy could significantly control tumor growth and prolong survival, and almost all mice in the dual-targeted formulation survived past 30 days, whereas all control mice died within 2 weeks. In another similar scheme, bismuth nanoparticles were coated in RBC membrane that was further functionalized with folate via lipid-insertion.[75] When irradiated with x-rays, the nanoparticles promoted the generation of free radicals and demonstrated the ability to control tumor growth in a 4T1 mouse tumor model. The formulation was also shown to be safe and was cleared from the body within 15 days.

A challenge for applying photodynamic therapy to tumors is that oftentimes the inner parts of the tumor is hypoxic, and the lack of oxygen will lead to decreased efficacy of the treatment. To address this issue, one group designed an oxygen self-enriched platform in which perfluorocarbon was used as an oxygen carrier.[76] To accomplish this, they employed a human serum albumin nanoparticulate core loaded with indocyanine green (ICG) as the photosensitizer and perfluorotributylamine as the oxygen carrier. To confirm successful loading of the photosensitizer, flow cytometry was used to demonstrate colocalization of ICG with a dye inserted into the RBC membrane. When irradiated in solution, the particles with encapsulated ICG were able to locally raise the temperature, while the addition of the perfluorocarbon in the cores significantly enhanced singlet oxygen production. Coating the dual-loaded cores with RBC membrane enabled immune evasion with reduced uptake into macrophages, but high uptake into cancer cells was preserved. With regards to enhancing photodynamic therapy, it was shown that after nanoparticle delivery into cells followed by irradiation, the level of intracellular ROS was increased, which translated to a marked reduction in cancer cell viability in vitro. Notably, the RBC-NP formulation circulated in the blood for much longer than the uncoated formulation, which enabled significantly enhanced tumor uptake in a biodistribution study with tumor-bearing mice. Finally, upon treatment, the nanoparticle group with irradiation exhibited significantly controlled tumor growth, with virtually all of the tumors having been eliminated over the course of 2 weeks.

In a similar work, oxygen delivery was used to enhance cancer radiotherapies. To develop this formulation, perfluorocarbon was loaded into PLGA cores, then cloaked with RBC membrane.[77] It was shown that the particles had good oxygen-carrying capacity, and significantly raised oxygen levels when pre-oxygenated and added to deoxygenated water. The membrane-coated particles were able to circulate for significantly longer than the uncoated perfluorocarbon-loaded PLGA nanoparticles. Tumor histology taken 24 hours after injection of the particles into 4T1 tumor-bearing mice demonstrated that the nanoparticles could traverse past the vasculature into the interior of the tumor, while intact RBC controls localized only with vessels. To confirm the ability of the nanoformulation to oxygenate tumors, photoacoustic imaging revealed that there was more oxygenated hemoglobin residing in the tumor for the membrane-coated particles compared with the uncoated group. Comparing tumor histological sections from both groups over time, the coated formulation showed decreasing hypoxyprobe signal and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α signal, indicating hypoxia relief. Finally, to test their hypothesis, the nanoformulation was administered and 24 hours later x-rays were used to irradiate the tumor. It was demonstrated that nanoparticle pre-administration improved the efficacy of x-ray irradiation, and the effectiveness could be easily visualized 24 hours after treatment using histology. This example proved to be a valid strategy for rationally combining different modalities to maximize efficacy based on inherent tumor biology.

3.3 Detoxification

Beyond traditional nanomedicine modalities such as drug delivery and imaging, the use of natural membrane coatings opens up additional applications that leverage the biological interactions inherent to surface proteins found on the cell surface. One such area is detoxification, which takes advantage of the fact that most toxins, regardless of their mode of action, must in some way interact with cellular membranes.[78] Further, these interactions are often mediated by specific cellular receptors, with strong affinities that can easily be leveraged. To prove this concept, RBC membrane-coated nanosponges were employed to neutralize α-hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus (Figure 4).[79] By incubating the nanosponges with the toxin, it was possible to completely abrogate the hemolytic effect of the toxin. Neither PEGylated PLGA nanoparticles nor PEGylated liposomes were able to neutralize the toxin in this manner, as neither could bind an appreciable amount of the toxin. Further, it was demonstrated that RBC vesicles alone also could not prevent hemolysis, likely due to their ability to fuse with healthy RBCs and transfer the hemolytic toxins. This is something that is believed to be prevented when membrane is coated onto a stabilizing nanoparticle substrate. The toxin neutralization effect was demonstrated in vivo by subcutaneously administering the toxin alone or pre-complexed with nanosponges. With nanosponge complexation, there was no visible skin damage, while toxin alone caused significant lesion formation. Finally, in a lethal toxin challenge model, the RBC nanosponges were able to significantly enhance survival in both a prophylactic and therapeutic setting. This concept has also been proven for other toxins such as melittin,[79] as well as for streptolysin-O.[79,80]

Figure 4.

RBC membrane-coated nanosponges for toxin neutralization. Pore-forming toxins can insert into the RBC membrane on the surface of the nanosponges, where they are retained and neutralized. By safely sequestering the toxins, RBC nanosponges spare healthy RBCs from being lysed. Reproduced with permission.[79] Copyright 2013, Nature Publishing Group.

The ability of the RBC nanosponges to display efficacy in a bacterial infection model was studied more in depth using group A Streptococcus (GAS).[81] In vitro, it was demonstrated that the nanosponges could neutralize the bioactivity streptolysin-O, both preventing hemolysis and preventing the ability of the toxin to induce cell death on keratinocytes. Further, the nanosponges had a protective effect on macrophages, preventing both toxin-mediated and bacteria-mediated death. This also enabled a J774 macrophage cell line to enhance their killing of the bacteria, leading to lower bacterial recovery when co-incubated with the nanosponges, likely due to the decreased virulence of the bacteria once disarmed of their toxins. Further, the nanosponges also rescued the ability of neutrophils to kill the bacteria, with the effect being observed both in whole blood and for purified neutrophils. Fewer bacteria were recovered from culture, and there was a marked increase in the amount of neutrophil extracellular traps. Finally in a live murine infection model, mice were challenged subcutaneously with GAS bacteria, followed by treatment with the nanosponges. The nanosponge-based detoxification led to significantly decreased lesion sizes and a correspondingly lowered bacterial count. Decreased inflammation around the infected region was also observed.

The nanosponge concept has been applied in several different formats. In one instance, RBC nanosponges were incorporated into a hydrogel matrix for localized treatment of MRSA infection via toxin neutralization.[44] It was demonstrated that, as the amount of crosslinker used was increased, fewer nanosponges were released from the hydrogel over time. Additionally, absorption capacity significantly increased for the nanosponge-incorporated hydrogel versus an empty hydrogel. From a functional perspective, the nanosponge gel was able to prevent hemolysis from both pure α-hemolysin and supernatant from α-hemolysin-rich MRSA culture. In vivo, the gel was able to facilitate retention of the nanosponge locally at the site of injection, with about 80% of the nanosponges left in the hydrogel at the site of injection after 2 days. In comparison, free nanosponges were only retained at a rate of around 25% over the same time period. The retention enabled effective neutralization of a bolus dose of α-hemolysin administered subcutaneously. To study the antibacterial efficacy of the nanosponge gel, a live subcutaneous infection model of MRSA was initiated followed by injection with the nanosponge gel or empty hydrogel. The nanosponge-containing formulation significantly reduced lesion formation, preventing a major symptom of the bacterial infection. Such nanosponge-hydrogel platforms can also be made using 3D bioprinting with custom design templates, such as porous discs to filter blood for toxin absorption with minimal disruption to blood flow.[82] As described earlier, a nanogel system has also been employed for simultaneous antibiotic delivery and detoxification.[65] Finally, nanomotors have been use to create “motor sponges” capable of directed movement.[83] In the system, gold nanowire motors capable of being propelled by ultrasound were employed. After successfully confirming membrane coating and validating coverage with a thiolated dye exclusion assay, propulsion was demonstrated, with the velocity of the motor sponges increasing with increasing transducer voltage at a frequency of 2.83 MHz. The propulsion could also be performed in whole blood, which suggests applicability towards further in vivo use. Finally, it was demonstrated that, with ultrasound, the motor sponges were able to more effectively neutralize toxin compared with unmanipulated motor sponges, which is likely due to an increase in the probability of toxin interaction.

The concept of nanosponges has also been demonstrated for detoxification of small molecules. In one example, organophosphates were shown to be detained using RBC nanosponges.[84] This class of small molecule toxins include commonly used pesticides, as well as biological warfare agents like VX and sarin gas. Their toxic effect occurs by the irreversible inactivation of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme expressed at neural synapses that is responsible for breaking down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Accumulation of acetylcholine results in constant activation of the nervous system, which can be lethal. As RBCs also express AChE, it was demonstrated that RBC nanosponges could effectively bind to dichlorvos, a model organophosphate, and prevent its ability to deactivate endogenous AChE. This effect was exclusive to membrane-coated nanoparticles, as neither PEGylated liposomes nor polymeric nanoparticles could prevent deactivation. In both intravenous and oral models of dichlorvos challenge, the RBC nanosponges could therapeutically rescue the mice, which died within minutes when left untreated. This allowed the mice to retain a majority of endogenous RBC AChE activity, which recovered to baseline within 4 days after treatment. In another example, RBC membrane-coated nanoparticles were used as nanoabsorbents to prevent the activity of toxic small molecule drugs.[85] The effect was demonstrated to be charge-dependent, as they could bind DOX, which is positively charged, very effectively, but not methotrexate. While both bare-PLGA nanoparticles and RBC nanoabsorbents could bind drug, only the coated particles were stable in serum. It was finally shown that cell viability could be rescued after exposure to DOX in the presence of the RBC nanoabsorbents.

In the final example, nanosponges have been used to address autoimmune disorders mediated by pathological antibodies.[46] In autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), the body produces antibodies against its own RBCs, which facilitates the destruction of healthy cells and can lead to dangerously low erythrocyte counts. While such autoimmune disorders can be addressed via broad immunosuppression, these treatments are nonspecific and can carry significant risks. Other more drastic treatment options include splenectomy or the use of cytotoxic drugs, which can have severe consequences. To address these issues, it was proposed that RBC nanosponges could serve as decoys for the autoimmune antibodies, thereby rescuing healthy RBCs from attack. In vitro, the nanosponges were confirmed to effectively bind anti-RBC antibodies, preventing their ability to agglomerate RBCs in an agglutination assay. Further, pre-complexation prevented ill effects of antibody administration intraperitoneally, which normally causes a drastic reduction of RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit levels. It was further demonstrated that the RBC nanosponges could treat AIHA in a therapeutic scenario using an induced anemia mouse model. Importantly, there was no detectable presence of anti-RBC antibodies in healthy mice challenged with nanosponges complexed with antibodies, indicating that the treatment would likely not elicit further autoimmunity.

3.4 Immune modulation

With the ability of the RBC nanosponges to neutralize biological and chemical toxins, the platform has a valuable niche in vaccine design. The first example of employing RBC nanosponges for immune modulation involved their use for antivirulence vaccination (Figure 5).[86] In this case, the natural affinity of RBC nanosponges for certain bacterial toxins and the nanosponges’ ability to neutralize these virulence factors were leveraged to safely deliver the toxins back to the immune system in the form of a “nanotoxoid”. This strategy can be used to overcome challenges facing traditional toxoid vaccines, which are generated either by chemical or thermal denaturation, or by subunit engineering. While such approaches make the toxin safe to administer, they often come at the expense of decreased immunogenicity or antigenicity. In this work, it was confirmed that the toxicity of α-hemolysin from S. aureus was attenuated in a time-dependent fashion when heated, underscoring the delicate balance that must be struck using such a denaturation approach. Nanotoxoids fashioned from α-hemolysin inserted into RBC nanosponges, on the other hand, were completely safe both in vitro and in vivo without the need for denaturation. When administered into mice, the nanotoxoid formulation consistently outperformed a heat-denatured toxin formulation, which ultimately translated to improved survival and reduced skin lesion formulation in animal studies involving intravenous and subcutaneous challenge, respectively, of bolus toxin. The approach has been further demonstrated to promote germinal center formation, indicating the ability of nanotoxoids to induce B cell maturation, and can significantly reduce bacterial burden in a live MRSA challenge model.[87]

Figure 5.

RBC membrane-coated nanotoxoids for antivirulence vaccination. a) Nanotoxoids are fabricated by inserting pore-forming toxins into RBC membrane-coated nanoparticles, a process that neutralizes their toxicity. Reproduced with permission.[86] Copyright 2013, Nature Publishing Group. b) Without protective immunity, subcutaneous injection of MRSA bacteria will cause the formation of skin lesions. c) After immunization, the immune system produces antibodies that can neutralize toxins and lessen cell damage at the site of infection, reducing bacterial colonization and invasiveness. Reproduced with permission.[87] Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH.

The concept of nanotoxoids has recently been expanded to be adapted for on-demand fabrication using naturally derived bacterial secretions.[88] A challenge in the design of antivirulence vaccines is that oftentimes bacteria will secrete a multitude of toxins, whereas most vaccines train the immune system against only one antigen. This can ultimately compromise efficacy, resulting in an inability to effectively combat live bacterial infection. The use of individual toxins also requires prior knowledge of their function and the ability to purify the toxin either from the natural source or recombinant. At times, even extensive knowledge about a toxin does not guarantee that it can be applicable towards vaccine design. To address this, RBC nanosponges were incubated with hemolytic protein fractions derived directly from MRSA bacteria culture. It was confirmed that, even after washing away unbound proteins, the nanosponges could retain several characteristic toxins, including α-hemolysin γ-hemolysin, and Panton-Valentine leukocidin. It was also shown that nanosponge complexation helped to completely attenuate the toxicity of the hemolytic proteins, preserving both RBCs and dendritic cells. For the protein fraction itself, even extensive and harsh heat denaturation could not completely remove the original toxicity. Multi-antigen nanotoxoids prepared from nanosponges complexed with the hemolytic proteins were further demonstrated to be safe in vivo and could induce significant germinal center formation. Importantly, elevated antibody titers were demonstrated for all three toxins compared with the heat denatured formulation. Finally, in models of both skin infection and bacteremia, vaccination with the multi-antigen nanotoxoid formulation significantly decreased the burden of disease. This style of on-demand nanotoxoid fabrication has the potential to be expanded to many other types of bacteria using different kinds of cell membranes or protein preparations.

In addition to antibacterial vaccines, RBC-NPs have also been explored in antitumor vaccination schemes. To facilitate delivery, RBC membrane was coated onto PLGA nanoparticles where the polymer was pre-conjugated to a peptide sequence found in hgp100, a melanoma-associated antigen.[89] By employing a thiol bond for linking the peptide antigen, the antigen release was sensitive to reducing environments, which could potentially aid in intracellular antigen delivery. The particle was further functionalized with a mannose group via the lipid-insertion technique to more efficiently localize to antigen presenting cells in vivo. Finally, a toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 agonist, monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA), was included as an immunological adjuvant and was able to facilitate dendritic cell maturation. In a prophylactic vaccination scenario, formulations were administered three times before challenge, and the targeted RBC-NP formulation with MPLA successfully prevented tumor occurrence in a B16-F10 tumor model. Further, the formulation demonstrated significant ability to control tumor growth in a therapeutic scenario, leading to reduced primary tumor growth and metastatic lesion formation. This efficacy was correlated to enhanced T cell responses. Finally, it was demonstrated that, despite the inclusion of an adjuvant with RBC membrane material, the approach was safe and did not generate autoimmunity against endogenous RBCs.

3.5 Detection

While examples are currently limited, membrane-coated particles have also been employed for biodetection schemes. In one example, RBC-NPs have been employed to bind and enrich influenza viruses.[90] To facilitate viral entry into cells, virus attachment to cells is initiated through interaction between hemagglutinin on the virus surface and sialic acid on cell membranes. It was proposed that RBC-NPs could take advantage of RBC surface sialic acid to also bind to the viruses. RBC membrane was first coated onto superparamagnetic iron oxide-containing PLGA cores, then immunogold staining and electron microscopy was used to confirm the core-shell structure and an abundance of sialic acid moieties on the surface of the coated particles. Upon mixing of influenza viruses and the RBC-NPs, both dynamic light scattering and nanoparticle tracking analysis showed population size increases indicative of particle binding, a phenomenon that was not observed during incubation of the viruses with PEGylated nanoparticles. Application of a magnetic field was subsequently used to separate out and enrich bound viruses. This extracted sample could then be used for different practical applications such as titer studies, plaque assays, and polymerase chain reaction with enhanced signal due to viral enrichment during the isolation process. Such viral isolation and enrichment are valuable for research and diagnostics on low concentration samples or with low sensitivity assays.

RBC nanosponges have also been used to detain, enrich, and identify unknown cell-specific effector proteins secreted by pathogens.[91] For this endeavor, human and mouse RBCs were used to make RBC nanosponges, along with mouse macrophage-coated nanosponges. These particles were incubated with the supernatant of pathogens in order to bind any cell membrane-targeted virulence factors that were present. Loaded nanosponges were then purified out from unbound components, digested, and the proteins were precipitated out and processed for identification using a quantitative mass spectrometry technique. With this “Biomimetic Virulomics” workflow, GAS-secreted virulence factors against human RBCs were enriched and identified; this included known RBC-attacking toxins, as well as proteins with currently no well-defined function. Additionally, the technique was also applied to analyze the affinity of protein secretions from Schistosoma mansoni eggs towards mouse RBCs and macrophages, demonstrating different binding profiles depending on the membrane type. In the future, this workflow can be broadened using other types of cell membrane-coated nanosponges to identify cell-specific virulence factors produced by almost any pathogen in a high throughput and precise manner.

4. Platelet Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles

With the success of RBC-NPs, other types of blood cells with unique functionalities have also been investigated as membrane sources. One important cell type that has been explored is platelets, which are anuclear fragments from megakaryocytes. The main function of platelets is maintaining hemostasis, as they are naturally recruited to sites of vascular injury to trigger a cascade that leads to clot formation, starting the healing process. Additionally, platelets have various other functions and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of diseases, ranging from cancer and atherosclerosis to bacterial infections. Like the immunomodulatory markers on RBCs, these disease-relevant platelet functions are largely a consequence of their surface marker expression, which can be transferred onto nanoparticles via membrane coatings.

4.1 Drug delivery

In the first instance of using platelet membrane to coat nanoparticles, a polymeric PLGA core was employed (Figure 6).[24] Platelet membrane was obtained using a repeated freeze-thaw process, and coated onto the polymeric cores, forming platelet membrane-coated nanoparticles (PNPs). Physicochemical characterization showed increases in size and zeta potential as indicators of successful coating, which was further confirmed by the characteristic core-shell structure shown by TEM. Using immunogold staining for extracellular CD47, it was demonstrated that the membrane was coated onto the cores largely in the right-side-out orientation. Importantly, it was confirmed that the resulting PNPs carried the entire array of platelet surface markers on their surface, including important immunomodulatory proteins as well as those implicated in binding interactions. These proteins, specifically the collagen binding proteins and CD47, were shown to retain their functionality. The coated nanoparticles were confirmed to bind human type IV collagen via membrane glycoprotein receptors, which is one of the major functions of platelets. They also had reduced macrophage uptake compared with bare nanoparticles, an effect that was reduced by blocking the CD47 present on the surface, and the membrane coating also reduced complement activation. Prior to in vivo use, it was confirmed that potentially thrombogenic compounds normally present within platelets were not present in the final formulation, leading to reduced concerns of spontaneous activation and clotting of endogenous platelets. Further, the PNPs were stable both in solution and after reconstitution from a lyophilized state, ensuring their suitability for injection even after extended storage. Finally, the particles did not lead to any appreciable toxicity in a blood chemistry panel.

Figure 6.

Platelet membrane-coated nanoparticles (PNPs) for biointerfacing. Nanoparticles coated with platelet membrane can utilize a unique set of transferred surface integrins and markers to evade the immune system and bind to sites that naturally recruit platelets. PNPs can deliver antineoplastic drugs to damaged vasculature by binding to exposed collagen and can kill pathogens by binding to them and releasing loaded antibacterial drugs. Reproduced with permission.[24] Copyright 2015, Nature Publishing Group.

To prove the applicability of these particles towards the treatment of diseases, two different animal models were employed. In the first, DTX was loaded into the PLGA cores using a co-preciptation method and used to treat post-angioplasty restenosis. Coronary angioplasty is an important procedure that can manually clear occluded vessels, but commonly causes vascular injury. The intimal layer often dramatically thickens in response and prevents flow through the vessels, causing restenosis. In a rat model of angioplasty-induced arterial injury, the PNPs were shown to target damaged vasculature in vivo and could be retained at the site for over 120 hours, while intact arteries did not appreciably bind the particles. The extended delivery of DTX by PNPs significantly decreased the overgrowth of the intimal layer in the DTX-loaded PNP group, whereas unloaded PNPs and free DTX were all similar to the untreated group in developing restenosis. The ability of the PNPs to bind to exposed collagen may also have implications in the future for the direct treatment of atherosclerosis, in which fatty plaque buildup revolves around collagen, smooth muscle cell and macrophage proliferation, and arterial damage.

In the second model, antibiotic resistant MRSA were employed. The bacteria are known to express a serine-rich adhesin for platelets, and oftentimes bacteria will bind to platelets to act as a shield and prevent detection by the immune system. By incubating PNPs with MRSA in vitro, binding was visually confirmed by scanning electron microscopy as well as by flow cytometric analysis. Afterwards, the antibiotic vancomycin was loaded into the particles using a double emulsion technique. Vancomycin dissolved in basic solution was sonicated with PLGA to form the first emulsion, then sonicated again in an aqueous solution to form a water/oil/water emulsion. The platelet membrane coating around the vancomycin particles allowed for increased binding, better targeting of the antibiotic to the bacteria, and improved bactericidal efficacy in vitro. In vivo, a systemic infection model was employed. Mice were challenged with MRSA252 bacteria and subsequently treated with intravenous injections of the vancomycin-loaded nanoparticles. It was demonstrated that the PNP formulation consistently outperformed both free drug as well as drug loaded into RBC-NPs. Notably, the particles outperformed free drug, which was administered at a 6 times higher dose. The improved efficacy at a drastically lower drug dose highlights the significant impact of targeted delivery and its implications for addressing hard to treat bacterial infections.

With their relevance in tumorigenesis, platelet membrane-coated nanocarriers have also been widely used for cancer drug delivery. In the first example, platelet membrane was coated around DOX-loaded nanogels.[92] The nanogels were fabricated via a single emulsion method by mixing acrylamide monomers and crosslinkers in the organic phase with an aqueous phase containing DOX, hexane, and surfactants. During the mixing of the two phases, tetramethylethylenediamine was added to initiate the polymerization of the acrylamide, thus forming nanogels encapsulating DOX. An acid-labile crosslinker was selected to bestow environmental sensitivity to the final formulation, which translated to the increased release of DOX in lower pH solutions in vitro. The formulation was further functionalized with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) to further induce cell death via binding with death receptors on cancer cells. The combination of DOX and TRAIL in the nanoparticle formulation led to a potent formulation against a human breast cancer cell line in vitro, due to the synergy of inducing apoptosis using both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. In vivo, the membrane-coated formulation demonstrated enhanced tumor targeting, likely due to the presence of P-selectin on the nanoparticle surface, which targets the overexpressed CD44 on the breast cancer cells. Finally, in an MDA-MB-231 tumor xenograft model, the nanoformulation was able to strongly control tumor growth, with almost no observed growth over the observation period, and significantly reduced the number of metastatic nodules. In both cases, efficacy required the platelet membrane coating, highlighting its ability to specifically deliver drugs to the target site of interest using natural targeting ligands found on the original cell.

In another example of cancer treatment, platelet-functionalized silica particles were used to achieve targeted delivery to circulating tumor cells.[93] In the work, the authors took advantage of the fact that cancer cells in the bloodstream can promote thrombosis and bind to platelets via fibrin deposition to evade destruction by immune cells. Using a sucrose gradient method to isolate platelet membrane-derived vesicles, the purified material was coated onto silica particles via (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES) functionalization. The resulting coated particles demonstrated a rough morphology compared to the relatively smooth exterior of uncoated particles. Immunostaining was used for both flow cytometry and fluorescent imaging to confirm the preservation of platelet proteins markers and glycans on the particles. To model the adhesion of the coated particles to fibrin under blood flow conditions, the particles were run through a fibrin-coated microtube. Membrane-coated particles were found to strongly adhere to the fibrin in the presence of calcium, confirming the thrombus-targeting property of the particles even in a fluid environment. To incorporate a therapeutic payload, TRAIL was attached to the particle surface through biotin-streptavidin interaction. The process of conjugation did not affect the potency of the ligand, and the particles could kill cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner. In vivo, it was demonstrated that in a circulating tumor cell model where mice were injected with cancer cells followed by the particles, membrane functionalization enabled efficient colocalization of the two. Finally, the same procedure was used with a luciferase-expressing tumor cell line to test efficacy, and drastically reduced luciferase signal was found in the lungs of mice treated with the membrane-coated particles functionalized with TRAIL.