Abstract

Permanent hearing loss is often a result of damage to cochlear hair cells, which mammals are unable to regenerate. Non-mammalian vertebrates such as birds replace damaged hair cells and restore hearing function, but mechanisms controlling regeneration are not understood. The secreted protein bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) regulates inner ear morphogenesis and hair cell development. To investigate mechanisms controlling hair cell regeneration in birds, we examined expression and function of BMP4 in the auditory epithelia (basilar papillae) of chickens of either sex after hair cell destruction by ototoxic antibiotics. In mature basilar papillae, BMP4 mRNA is highly expressed in hair cells, but not in hair cell progenitors (supporting cells). Supporting cells transcribe genes encoding receptors for BMP4 (BMPR1A, BMPR1B, and BMPR2) and effectors of BMP4 signaling (ID transcription factors). Following hair cell destruction, BMP4 transcripts are lost from the sensory epithelium. Using organotypic cultures, we demonstrate that treatments with BMP4 during hair cell destruction prevent supporting cells from upregulating expression of the pro-hair cell transcription factor ATOH1, entering the cell cycle, and fully transdifferentiating into hair cells, but they do not induce cell death. By contrast, noggin, a BMP4 inhibitor, increases numbers of regenerated hair cells. These findings demonstrate that BMP4 antagonizes hair cell regeneration in the chicken basilar papilla, at least in part by preventing accumulation of ATOH1 in hair cell precursors.

Keywords: BMP4, ATOH1, hair cell, regeneration

1. INTRODUCTION

Auditory hair cells are mechanoreceptors located in the cochlea that encode sound and are required for hearing. Hair cells are often damaged by ototoxic drugs, noise exposure, or aging. Because mature mammals cannot replace cochlear hair cells (e.g., Roberson and Rubel, 1994; Chardin and Romand, 1995; Sobkowicz et al., 1997; Forge et al., 1998), hearing deficits caused by hair cell loss are permanent. By contrast, birds regenerate auditory hair cells and restore hearing within a few weeks (Cruz et al., 1987; Cotanche, 1987; Corwin and Cotanche, 1988; Ryals and Rubel, 1988; reviewed in Bermingham-McDonogh and Rubel, 2003; Stone and Cotanche, 2007). In birds, auditory hair cells reside in the basilar papilla, a sensory epithelium located in the cochlear duct. Replacement hair cells are derived from adjacent supporting cells by either mitotic division (Hashino and Salvi, 1993; Stone and Cotanche, 1994) or direct transdifferentiation, during which supporting cells phenotypically convert into hair cells without dividing (Adler and Raphael, 1996; Roberson et al., 2004; Shang et al., 2010).

The mechanisms that regulate hair cell regeneration in mature animals are largely unknown. During vertebrate embryogenesis, the transcriptional activator ATOH1 drives expression of many hair cell-specific genes (Cai et al., 2015) and is necessary for both hair cell differentiation and survival (Bermingham et al., 1999; Itoh and Chitnis, 2001; Chen et al., 2002; Millimaki et al., 2007; Pan et al., 2012; Cai et al., 2013; Chonko et al., 2013). ATOH1 is transcribed at a low level in developing hair cell progenitors (Bermingham et al., 1999; Woods et al., 2004). Levels of ATOH1 transcript and protein become elevated in nascent hair cells and diminish once hair cells mature (e.g., Chen et al., 2002; Woods et al., 2004). In non-mammals, ATOH1 expression is re-activated during hair cell regeneration. Shortly after hair cell damage occurs, most supporting cells (hair cell progenitors) in the area of damage appear to upregulate ATOH1 transcription (Lewis et al., 2012). However, only a subpopulation of supporting cells or post-mitotic precursor cells accumulates ATOH1 protein and transdifferentiates into hair cells (Cafaro et al., 2007; Cotanche and Kaiser, 2010; Lewis et al., 2012). Overexpression of ATOH1 drives higher rates of supporting cell division and direct transdifferentiation in the chicken basilar papilla (Lewis et al., 2012) and promotes regeneration of hair cell-like cells in mammalian epithelia after damage at mature stages (e.g., Kawamoto et al., 2003; Shou et al., 2003; Atkinson et al., 2014; Staecker et al., 2014).

Bone morphogenetic proteins, or BMPs, are critical regulators of cellular development (reviewed in Brazil et al., 2015). BMP4 antagonizes transcription and accumulation of ATOH1 in the developing cerebellum and in medulloblastomas (Zhao et al., 2008). In chickens, BMP4 is transcribed in the auditory sensory primordium at early stages of embryogenesis and in auditory hair cells at late stages (Wu and Oh, 1996; Oh et al., 1996; Cole et al., 2000). The functions of BMP4 signaling in avian hair cell development are somewhat unclear. Pujades et al. (2006) showed that inhibition of BMP4 in cultured chick otocysts with the antagonist noggin (NOG) increases ATOH1 transcripts and hair cell numbers, and addition of soluble BMP4 has the opposite effect. However, Li and colleagues (2005) showed that BMP4 increases hair cell numbers in the developing chicken inner ear, and inhibition of BMP4 has the opposite effect.

BMP4’s role during hair cell regeneration has not been examined. Therefore, we evaluated expression of BMP4 signaling pathway genes in the chicken basilar papilla after hair cell damage, and we tested effects of activating or inhibiting BMP4 signaling in cultured basilar papillae. As described below, our results indicate that BMP4 is a potent negative regulator of hair cell regeneration, and reduction of BMP4 signaling is likely a critical step to enable supporting cells to replace hair cells after damage.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animal care and treatment

Chickens were obtained in two manners. Fertile eggs of chickens (Gallus gallus, White Leghorn) were purchased from Charles River Labs (Wilmington, MA) or Featherland Farms (East Pearl Coburg, OR) and stored in a refrigerator for up to one week. Eggs were placed in a humidified incubator until hatching. Alternatively, hatchlings were purchased from Belt Hatchery (Fresno, CA) or Featherland Farms (East Pearl Coburg, OR). Hatchlings generated in each manner were housed in heated brooders with water and food. Both male and female birds were used. All procedures were approved by the University of Washington Animal Care Committee and conformed to federal standards.

2.2. Gentamicin injections

Post-hatch chicks of 7-10 days old were injected with the ototoxic aminoglycoside antibiotic, gentamicin (subcutaneous, 1×300 mg/kg on 2 consecutive days, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI), which kills hair cells in the proximal region when administered systemically. After injection, chicks were returned to brooders for recovery until 4 or 8 days following the first gentamicin injection. Chickens were killed by decapitation. The middle ear was opened, and the columella (middle ear bone) was removed. For tissue being prepared for in situ hybridization (ISH), middle ears were opened, and heads were immersion-fixed in a solution of 0.2mM EGTA and 3.7% formaldehyde in 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C. After fixation, cochlear ducts (containing the basilar papilla) were dissected and placed in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated PBS for removal of the tegmentum vasculosum and the tectorial membrane, structures that overlie the basilar papilla. Cochlear ducts were rapidly dehydrated in a graded methanol series and stored at -80°C until ISH was performed (described below). For tissue being prepared for immunohistochemistry, cochlear ducts were removed immediately after decapitation and fixed in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (Stone and Rubel, 1999) for 30 minutes at room temperature and stored in PBS at 4°C. For all basilar papillae, the tectorial membrane was mechanically removed by dissection prior to dehydration (for ISH) or prior to storage in PBS (for immunolabeling).

2.3. Organ cultures

Chicks between days 7-10 post-hatch were killed by decapitation, and heads were rapidly immersed in 70% ethanol for 1 minute. Cochlear ducts were dissected, and the tegmentum vasculosum was removed. Each cochlear duct was placed in an individual well containing 450 μL of culture media and maintained at 37°C in 95% environmental room air/5% CO2 for various periods (described for each experiment in Results). Culture media were composed of Dulbecco’s Minimal Essential Medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI) plus 1% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA). For the first few days, all cultures were treated with 172 μM streptomycin by generating a 1:100 dilution of penicillin-streptomycin solution (catalog # P433 [Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI]). Streptomycin, an ototoxic aminoglycoside antibiotic, kills hair cells throughout the entire basilar papilla when applied in vitro, including proximal and distal halves (Shang et al., 2010), but penicillin is not harmful to hair cells. After ototoxin treatment, cultures were rinsed and maintained in streptomycin-free media. Cultures were treated with 10 ng/ml BMP4 (human recombinant, #314-BP, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 500 μg/ml noggin (NOG) (mouse FC chimera, #719-NG, R&D Systems), or no additive, as described in Results. Culture media were replaced daily at half-volume for maintenance or full-volume when changing to another stage of the experiment (e.g. transitioning from media with ototoxin to media without ototoxin). Cochlear ducts were fixed as described above for ISH or immunolabeling. For each experiment, at least 3 runs were performed. For each run, at least 4 experimental and 4 control organs were included.

2.4. Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Using non-radioactive in situ hybridization (ISH) previously described (Henrique et al. 1995; Stone and Rubel 1999), mRNA was detected in whole-mount cochlear ducts from which the tegmentum vasculosum and tectorial membrane had been removed. Digoxygenin (DIG)-conjugated riboprobes were synthesized from plasmids containing fragments or complete cDNA of the following chicken genes: BMP4 (obtained from Dr. Doris Wu, National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health; Roberts et al., 1995), BMPR1A and BMPR1B (obtained from Dr. Jeanette Hyer, Department of Neurosurgery, University of California San Francisco; Zou et al., 1997; Hyer et al., 2003), BMPR2 (obtained from Dr. Tsutomu Nohno, Department of Molecular and Developmental Biology, Kawasaki Medical School, Kurashiki, Japan; Kawakami et al., 1996), ID1, ID2, ID3, and ID4 (gifts from Dr. Marianne Bronner, Caltech; Kee and Bronner-Fraser, 2001a,b,c), and ATOH1 (a gift from Dr. Fernando Giraldez, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain; Pujades et al., 2006). Riboprobes were detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody and NBT/BCIP substrate (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). To examine gene expression after gentamicin treatment in vivo, 4-8 basilar papillae were examined per time-point for each gene. To compare gene expression in organ cultures, at least 8 specimens (4 experimental, 4 control) from the same culture run were processed in parallel, with 2–3 culture runs performed for each experiment. Some cochlear ducts were embedded post-ISH in plastic and sectioned at 2-3 μm to better visualize cellular localization of the hybridization reaction.

2.5. Immunohistochemistry

At the end of each culture period or immediately following cochlear duct removal, auditory end organs were fixed with buffered 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes, rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and stored at 4°C. Cochlear ducts were immunolabeled using standard methods (Stone and Rubel, 2000; Cafaro et al., 2007; Daudet et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2012). Organs were immersed in blocking solution (10% normal goat serum diluted in 0.05% TritonX-100 in PBS) for 30 minutes, then placed in primary antibody diluted in the same blocking solution overnight at 4°C or room temperature. We used the following primary antibodies. Rabbit anti-MYO6 (1:1000 dilution) and anti-MYO7A (1:1000 dilution) antibodies were purchased from Proteus Biosciences (Ramona, CA). Rabbit anti-TUBB3 antibody (1:500 dilution) was purchased from Covance (Redmond, WA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-ATOH1 (1:300 dilution) was provided by Jane Johnson (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center). Rat monoclonal anti-BrdU (1:400 dilution) was purchased from SeraLabs (Chestertown, MD).

After rinsing with PBS, organs were placed into secondary antibody solution for 2 hours. Secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores (Alexa 488, Alexa 594; 1:400 dilution each) were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA) or Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). For ATOH1 labeling only, we used Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to increase signal. We followed manufacturer’s specifications with few alterations (Cafaro et al., 2007). Organs were counter-labeled with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) at 0.1 mg/ml to detect nuclei. Organs were mounted on glass slides and coverslipped using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories).

2.6. Dead cell labeling

To assess apoptosis in cultured basilar papillae, we used terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) using an Alexa Fluor 488 kit from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Cultures were co-labeled with DAPI.

2.7. Imaging and quantitative analyses

Imaging of fluorescently labeled whole-mount basilar papillae was performed using an Olympus FV-1000 confocal microscope. Bright-field imaging of ISH was performed using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope. For qualitative analyses, at least 4 basilar papillae were examined for each experimental group. For quantitative analyses, the number of basilar papillae analyzed ranged from 3-13 per group. Sample numbers for each experiment are provided in Figure Legends.

It is important to note that streptomycin treatment in vitro leads to hair cell destruction throughout the basilar papilla (Shang et al., 2010), while gentamicin treatment in vivo causes hair cell destruction only in the proximal half (e.g., Bhave et al., 1995). In each group of basilar papillae (cultured with no additive, BMP4, or NOG), we estimated the density of hair cells (MYO6-positive cells), dying cells (TUNEL-positive cells), dividing (BrdU-labeled) supporting cells, or ATOH1-positive nuclei in the mid-distal region of each basilar papilla, located at ~70% distance from the proximal tip. This region was analyzed routinely, because it is wider and often better preserved than the proximal end, which can be injured during explantation. We counted cells in 65,273 μm2 mid-distal regions, which comprises ~10% of the basilar papilla’s area. Cell density was converted to number of cells per 10,000 μm2 of basilar papilla.

Because each cochlear duct was cultured alone in a well, each organ was included as a number (N) for each respective treatment group. Animal numbers for each experiment and group are provided in Figure Legends. Data were analyzed with ANOVA and, in some cases, a Dunnett’s or Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post hoc test, as indicated for each case in Results. For all comparisons, effects were considered statistically significant if p ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Hair cells were lost and regenerated after ototoxin treatment

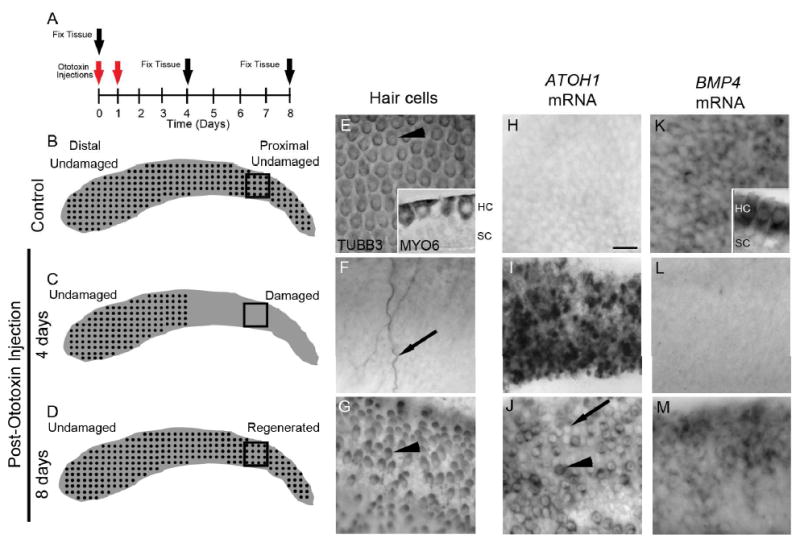

Prior studies demonstrated that injection of post-hatch chickens with gentamicin (ototoxin) results in complete loss of hair cells in the proximal one-third to one-half of the basilar papilla within 3-4 days (Bhave et al., 1995; Janas et al., 1995). At 3-7 days post-ototoxin, hair cell progenitors (supporting cells) divide and transdifferentiate into hair cells; regenerated hair cells begin to emerge in the damaged region by 4 days post-ototoxin (Stone and Rubel, 2000; Roberson et al., 2004; Cafaro et al., 2007). We performed experiments to confirm this time-course. Post-hatch chickens received one injection of ototoxin (gentamicin, at 200-250 mg/kg) on two consecutive days, and organs were harvested at 4 or 8 days after the first injection (Fig. 1A). Control birds received no ototoxin. Hair cells and nerve fibers were selectively labeled with antibodies to βIII tubulin (TUBB3; Stone et al., 1996; Stone and Rubel, 2000). The state of hair cells throughout the basilar papilla at each time is schematized in Fig. 1B-D, with each boxed region indicating the proximal region shown in Fig. 1E-M.

Figure 1. Changes in ATOH1 and BMP4 expression during in vivo hair cell damage and regeneration in the chicken basilar papilla.

A. The diagram demonstrates the design for experiments in Figs. 1-3, showing the times for ototoxin (gentamicin) injections (red arrows) and tissue fixation (black arrow). B-D. Schematics of basilar papillae showing the distribution of hair cells in control birds (B), at 4 days post-ototoxin (C), and at 8 days post-ototoxin (D). In control chicks (B), hair cells (black dots) are intact along the length of the sensory epithelium. In chicks at 4 days post-ototoxin (C), all hair cells are lost from the proximal (damaged) half of the basilar papilla but are preserved in the distal (undamaged) half. In chicks at 8 days post-ototoxin (D), regenerated hair cells are abundant in the proximal half; in the distal half, original hair cells remain undamaged. The black boxes positioned at the proximal end of the basilar papilla schematic demonstrate the approximate regions of the basilar papilla shown in E-M. E-G. TUBB3 immunolabeling of hair cells; surface views of whole-mount preparations. E. Hair cells (arrowhead) are evenly distributed throughout a control basilar papilla (proximal half shown). Inset is a cross-section of the basilar papilla at slightly higher magnification, showing MYO6 labeling in hair cells (HC) but not supporting cells (SC). F. At 4 days post-ototoxin, hair cells were eliminated from the proximal half of the basilar papilla, but some neurites remained (arrow). G. At 8 days post-ototoxin, hair cells were regenerated in the proximal half. Note the immature morphology of the regenerated hair cells (arrowhead): smaller cell bodies that are slightly elongated. H-J. ATOH1 mRNA labeling; surface views of whole-mount preparations. H. ATOH1 mRNA was not detected in control basilar papilla. I. ATOH1 mRNA levels were dramatically increased in the proximal half at 4 days post-ototoxin. J. At 8 days post-ototoxin, ATOH1 mRNA was expressed in some regenerated hair cells in the proximal half (arrowhead) but was absent from other, presumably more mature regenerated hair cells (arrow). K. BMP4 mRNA labeling; surface views of whole-mount preparations. BMP4 mRNA was highly expressed in hair cells in undamaged basilar papilla. Inset shows a transverse section of a control, undamaged basilar papilla that demonstrates BMP4 mRNA was highly expressed in hair cells (HC) but lacking in supporting cells (SC). L. At 4 days post-ototoxin, BMP4 mRNA was lost from the proximal half, reflecting hair cell destruction. M. At 8 days post-ototoxin, BMP4 mRNA re-emerged in regenerated hair cells in the proximal half. Scale bar shown in H = 10 μm and applies to panels E-M.

In control birds, antibodies to hair cell-selective proteins TUBB3 and MYO6 label intact hair cells throughout the basilar papilla (Fig. 1B,E; Hasson et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1996; Stone and Rubel, 2000). At 4 days post-ototoxin, TUBB3-positive hair cells were lost from the proximal half of the basilar papilla; only a few TUBB3-labeled nerve fibers persisted (Fig. 1C,F). Hair cells remained intact in the distal (undamaged) half of the basilar papilla (schematized in C). By 8 days post-ototoxin, regenerated hair cells had emerged in the proximal, damaged half (Fig. 1D,G), and hair cells in the distal half remained intact (schematized in D).

3.2. ATOH1 transcripts were upregulated in supporting cells after hair cell loss and enriched in regenerated hair cells as they differentiate

One of the earliest markers of regenerating hair cells is ATOH1 mRNA or protein, which is absent in mature hair cells and supporting cells but accumulates after hair cell damage in supporting cells when they transdifferentiate into hair cells (Cafaro et al., 2007; Cotanche and Kaiser, 2010; Lewis et al., 2012). Using in situ hybridization (ISH), we confirmed that ATOH1 transcripts were present at very low levels in undamaged basilar papillae (Fig. 1H). At 4 days post-ototoxin, once hair cell elimination had occurred, ATOH1 transcripts were upregulated in supporting cells in the damaged region (Fig. 1I). At 8 days post-ototoxin, ATOH1 transcripts were expressed in presumably regenerating hair cells (Fig. 1J). Some new hair cells expressed lower levels of ATOH1, suggesting they were more mature. No changes in ATOH1 expression were seen in the distal, undamaged region (not shown).

3.3. BMP4 transcripts were detected in mature and regenerated hair cells but were lost upon hair cell destruction

Bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) is a diffusible signaling molecule that is expressed in the sensory epithelia of the developing chick otocyst (Wu and Oh, 1996; Oh et al., 1996; Cole et al., 2000), where it antagonizes ATOH1 transcript accumulation (Pujades et al., 2006). To assess if BMP4 might have a similar role during hair cell regeneration, we examined BMP4 expression in basilar papillae, before and after hair cell loss and during hair cell regeneration using the time-line defined in Fig. 1A. Using whole-mount ISH with a previously described probe (Wu and Oh, 1996), we found that BMP4 transcripts were restricted to hair cells (Fig. 1K) and non-sensory cells near or within the abneural half of the basilar membrane (shown in Fig. 3B). They were not expressed in supporting cells. Four days after ototoxin, BMP4 mRNA labeling was eliminated from the proximal (damaged) half of the basilar papilla (Fig. 1L), concurrent with hair cell loss. At 8 days post-ototoxin, BMP4 mRNA was detected in regenerated hair cells in the damaged region (Fig. 1M). By contrast, BMP4 mRNA labeling did not appear to change in the distal undamaged region (data not shown).

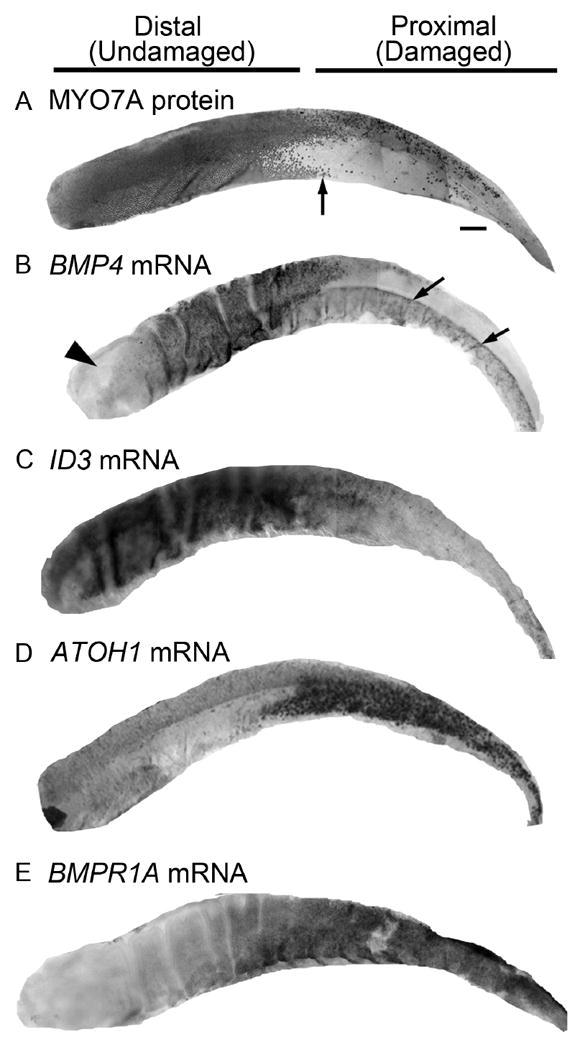

Figure 3. Expression patterns for ATOH1 and BMP4 pathway genes at 4 days post-ototoxin in the chicken basilar papilla.

All panels show whole basilar papillae at 4 days post-ototoxin (gentamicin). A. The labeling pattern of MYO7A protein, which is enriched in hair cells, demonstrates that hair cell loss was confined to the proximal half of the basilar papilla. Arrow points to the transitional zone between the proximal half, with extensive hair cell loss, and the undamaged distal half. B. BMP4 mRNA was abundant in hair cells in the distal half of the basilar papilla, while BMP4 mRNA labeling was absent from the proximal half. Some BMP4 mRNA labeling was retained in cells beneath the sensory epithelium, near the basilar membrane, on the abneural (lower) half only (arrows). Arrowhead points to distal-most region, where BMP4 expression is lower than in other regions of the epithelium under normal conditions. C. ID3 mRNA was abundant in supporting cells in the distal half, while ID3 mRNA labeling was decreased in the proximal half. D. ATOH1 mRNA was not detected in the distal half, while ATOH1 was highly upregulated in the proximal half. E. BMPR1A mRNA label was relatively low in the distal half compared to the proximal half. Scale bar in A = 100 μm and applies to all panels.

3.4. Transcripts for BMP4 receptors were detected in undamaged basilar papilla

We assessed transcripts for BMPR1A, BMPR1B, and BMPR2, the receptors for BMP4 (Feng et al., 2014; Goracy et al., 2012; Miyazono et al., 2010; van Wijk et al., 2007). Using whole-mount ISH, we localized receptor transcripts in basilar papillae from chicks that received no ototoxin using probes described previously (Kawakami et al., 1996; Zou et al., 1997; Hyer et al., 2003). To visualize cellular labeling, organs were sectioned (Fig. 2A-D). For reference, hair cell labeling is shown in Fig. 2A. Transcripts for BMP4 receptors were localized to hair cells and supporting cells (Fig. 2B-D). Transcripts for BMPR1B appeared to be present at higher levels in hair cells than supporting cells (Fig. 2C), while expression of BMPR1A and BMPR2 appeared similar in both cell types (Fig. 2B,D).

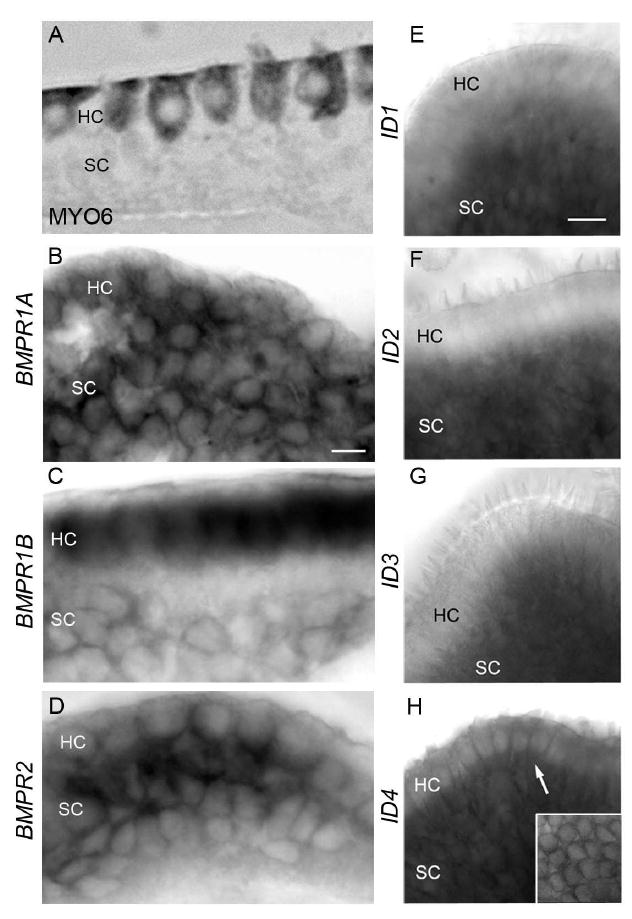

Figure 2. mRNA expression of BMP4 receptors and Inhibitors of DNA Binding 1-4 (IDs 1-4) in control basilar papillae.

All images are of undamaged basilar papilla A. Cross-section of basilar papilla immunolabeled for MYO6 illustrates the positions of hair cells (HC) and supporting cells (SC) in the basilar papilla. B. Cross-section demonstrates BMPR1A mRNA labeling in hair cells (HC) and supporting cells (SC). C. Cross-section shows BMPR1B transcript labeling in hair cells and in supporting cells to a lesser degree. D. Cross-section shows that BMPR2 transcripts are abundant in both hair cells and supporting cells. E. Side view demonstrates labeling of ID1 mRNA in supporting cells and little labeling in hair cells. F. Side view shows ID2 mRNA in supporting cells and little or no labeling in hair cells. G. Side view demonstrates ID3 mRNA labeling in supporting cells and little or no labeling in hair cells. H. Side view demonstrates strong ID4 mRNA labeling in hair cells (arrow) and supporting cells. Inset shows whole mount surface view of the basilar papilla with ID4 mRNA labeling in hair cells. Scale bar in B = 5 μm and applies to B-D. Scale bar in E = 10 μm applies to E-H.

3.5. Transcripts for IDs were detected in undamaged basilar papillae

We examined expression of the transcriptional cofactors inhibitors of DNA binding (Ids), which are known to act downstream of BMPs in various tissues (Miyazono & Miyazawa, 2002; Miyazono et al., 2010). In the developing inner ear, transcripts for IDs 1-4 are enriched in supporting cells, and IDs likely mediate BMP4’s inhibition of ATOH1 transcription during hair cell development (Jones et al., 2006 ; Kamaid et al., 2010). Whole-mount ISH using previously described probes (Kee and Bronner-Fraser, 2001a,b,c) revealed that, in undamaged basilar papillae, supporting cells express transcripts for ID1 (Fig. 2E), ID2 (Fig. 2F), and ID3 (Fig. 2G), while ID4 transcripts were expressed in hair cells and supporting cells (Fig. 2H).

3.6. Spatial distribution of transcripts for ATOH1 and BMP4 pathway proteins after hair cell loss

We explored regional changes in expression of ATOH1 and some BMP4 pathway transcripts at 4 days after ototoxin-mediated hair cell damage using whole-mount ISH. All images show the entire extent of the basilar papilla. Labeling for the hair cell marker myosin VIIa (MYO7A; Hasson et al., 1997)(Fig. 3A) demonstrates that hair cells were nearly completely lost from the proximal half of the basilar papilla but remained intact in the distal half. BMP4 transcripts were highly reduced in the proximal half but were retained distally (Fig. 3B), as expected, since there was little or no hair cell loss in the distal half. Further, BMP4 transcripts were retained in cells near or within the abneural half of the basilar membrane in the proximal region. BMP4 transcripts are naturally low in the distal-most portion of the basilar papilla (Fig. 3B). Transcripts for the BMP4 target gene, ID3, were reduced in the proximal, damaged half (Fig. 3C), mirroring changes in BMP4. ID2 also showed reduced mRNA expression in the damaged region (not shown). By contrast, ATOH1 and BMPR1A transcripts were increased in supporting cells in the proximal half (Fig. 3D,E), as were transcripts for BMPR1B and BMPR2 (not shown). The expression pattern for each gene in the distal half of undamaged organs was very similar to its expression pattern in the distal half of damaged organs (not shown), indicating that expression of the genes shown in Fig. 3 was not altered in the distal half after damage.

3.7. BMP4 reduced ATOH1 transcripts and protein in the damaged basilar papilla

Our results indicate that under normal conditions, when no new hair cells are being formed, BMP4 is expressed in hair cells and very little ATOH1 is expressed in supporting cells. Upon hair cell loss, BMP4 expression is lost, and ATOH1 mRNA levels are increased. These observations suggest BMP4 antagonizes ATOH1 expression and prevents supporting cell transdifferentiation when hair cells are intact, and upon hair cell damage, the loss of BMP4 signaling enables ATOH1 to be upregulated in supporting cells, which initiates hair cell regeneration.

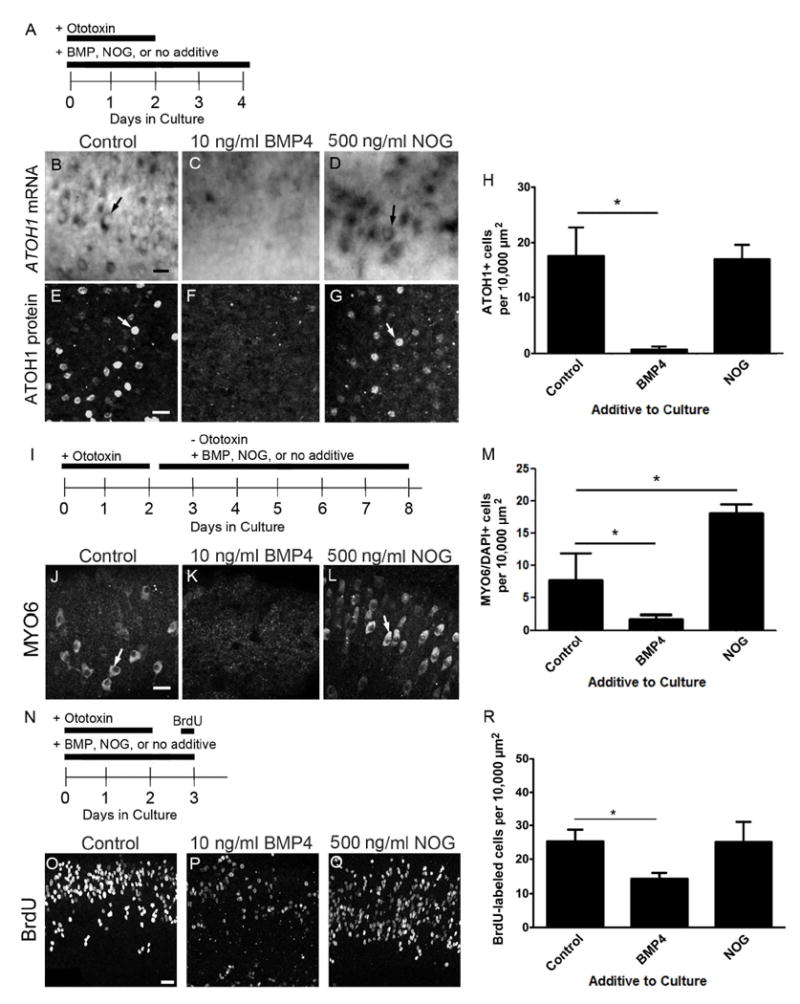

We reasoned that replacement of BMP4 during hair cell loss would prevent accumulation of ATOH1 mRNA, and inhibition of BMP4 with its antagonist noggin (NOG) might increase it. To test this hypothesis, cochlear ducts were explanted and cultured for two days with streptomycin, which is an ototoxin similar to gentamicin that we used for all culture experiments. Streptomycin treatment in vitro eliminates hair cells throughout the basilar papilla by the end of the treatment period, triggering hair cell regeneration in a similar time course as in vivo (e.g., Shang et al., 2010). After rinsing out the ototoxin, the organ cultures were treated for two additional days with (1) no additive, (2) recombinant BMP4 protein at 10 ng/ml, or (3) NOG (FC chimera) protein at 500 ng/ml (Fig. 4A). These doses were similar to those used in studies of cultured chick otocysts (Pujades et al., 2006). Cochlear ducts were processed for ISH to assess ATOH1 mRNA. In control cultures (no additive), ATOH1 mRNA expression was detected in cells throughout the basilar papilla (Fig. 4B), which based on their cell shapes are likely regenerated hair cells (see Fig. 1I,J). After BMP4 treatment, few ATOH1-expressing cells were seen (Fig. 4C). By contrast, ATOH1-expressing cells were numerous following NOG treatment (Fig. 4D). It is possible that some cells had more ATOH1 mRNA than others, but we did not quantify this.

Figure 4. BMP4 treatment reduced expression of ATOH1 mRNA and protein, and antagonized supporting cell division and hair cell regeneration in cultured chicken basilar papillae.

A. To evaluate effects on ATOH1 expression, organ cultures were treated with ototoxin (streptomycin) for 2 days to kill hair cells. Organs were maintained in 10 ng/ml BMP4, 500 ng/ml NOG, or no additive (control) during the ototoxin treatment period and then for 2 additional days. B-G. These panels show ISH labeling for ATOH1 mRNA (B-D) or immunofluorescence labeling for ATOH1 protein (E-G) in the mid-distal region of basilar papillae treated with either BMP4 (C,F), NOG (D,G), or no additive (control, B,E). H. Graph shows the average number of cells labeled by ATOH1 immunofluorescence per 10,000 μm2 of basilar papilla (+1 standard deviation) for each treatment group. Numbers of basilar papillae assessed were 7 for controls, 5 for BMP4-treated, and 3 for NOG-treated. I. To evaluate effects on hair cell regeneration, ototoxin was added to organ cultures for 2 days. Then, organs were maintained for 6 days in culture with no additive (control), 10 ng/ml BMP4, or 500 ng/ml NOG. J-L. Images show fluorescent labeling for MYO6 in the mid-distal region of basilar papillae treated with no additive (control, J), with BMP4 (K), or with NOG (L). M. Graph shows the average number of MYO6-labeled hair cells per 10,000 μm2 of basilar papilla (+1 standard deviation) for each group. Numbers of basilar papillae assessed were 7 for controls, 13 for BMP4, and 5 for NOG. N. To evaluate effects on supporting cell division, organ cultures were treated with ototoxin (streptomycin) for 2 days. Cultures were maintained in 10 ng/ml BMP4, 500 ng/ml NOG, or no additive (control) during the ototoxin treatment period and then for 1 additional day. BrdU was added for the last 4 hours in culture. O-Q show the mid-distal region of basilar papillae cultured without additive (control, O), with 10 ng/ml BMP4 (P), or with 500 ng/ml NOG (Q). R. Graph shows the average number of BrdU-labeled supporting cells per 10,000 μm2 of basilar papilla (+1 standard deviation) for each group. N = 5 basilar papillae per group. For graphs H, M, and R, significant changes between groups are indicated by an asterisk; error bars represent one standard deviation. Scale bars = 10 μm. Scale bar in B applies to B-D; scale bar in E applies to E-G; scale bar in J applies to J-L; scale bar in O applies to O-Q.

Next, we assessed effects of BMP4 on numbers of cells expressing ATOH1 protein. Cochlear ducts were cultured as described in Figure 4A, and ATOH1 protein was assessed via immunolabeling. ATOH1-positive nuclei were abundant in control and NOG-treated basilar papillae (Fig. 4E,G,H), but they were rare in BMP4-treated epithelia (Fig. 4F,H). One-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of treatment (df = 14, f = 32.28, p < 0.0001). Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparisons test indicated that the density of ATOH1-positive nuclei was significantly reduced in BMP-treated organs relative to controls (for control vs. BMP4, q = 7.598; for control vs NOG, q = 0.2422), but there was no difference between NOG-treated organs and controls.

These findings show that, in short-term cultures, BMP4 antagonizes the increase of ATOH1 transcripts and protein in regenerated hair cells, but treatment with the BMP4 antagonist NOG has little effect.

3.8. BMP4 antagonized hair cell regeneration in the damaged basilar papilla

Next, we tested the hypothesis that BMP4 treatment decreases the number of hair cells that are regenerated. Cochlear ducts were explanted and cultured for two days with ototoxin. After rinsing, organs were cultured for additional 6 days with 10 ng/ml BMP4, 500 ng/ml NOG, or no additive (Fig. 4I), allowing enough time for hair cells to differentiate and be identifiable by antibodies to MYO6 (Hasson et al., 1997; Shang et al., 2010).

In cultures with no additive (controls), regenerated hair cells were abundant throughout the basilar papilla (Fig. 4J,M). Treatment with BMP4 reduced the average density of hair cells (Fig. 4K,M), while treatment with NOG increased hair cell density (Fig. 4L,M), relative to controls. One-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of treatment (f = 24.36, df = 8, p=0.0013). Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparisons test showed that BMP4-treated organs and NOG-treated organs were both significantly different from controls (for control vs. BMP4, q = 2.935; for control vs. NOG, q = -8.570).

3.9. BMP4 antagonized proliferation of hair cell progenitors

Next, we tested if BMP4 treatment also reduces proliferation of hair cell progenitors. Cochlear ducts were cultured with ototoxin for 2 days, rinsed, and maintained for another day in ototoxin-free media. BrdU was added to media for the last 4 hours in culture to label dividing supporting cells (Fig. 4N). Culture media contained 10 ng/ml BMP4, 500 μg/ml NOG, or no additive for the entire 3-day culture period.

BrdU-positive nuclei were detected in the sensory epithelium of all organs (Fig. 4O-R), and one-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect of treatment (p=0.0021; f = 11.39, df = 13). Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparisons test indicated that the density of BrdU-labeled cells was significantly reduced in BMP-treated organs compared to controls (p<0.05, q for control vs BMP4 = 4.008, and q for control vs NOG = 0.0721), but there was no difference between NOG-treated organs and controls.

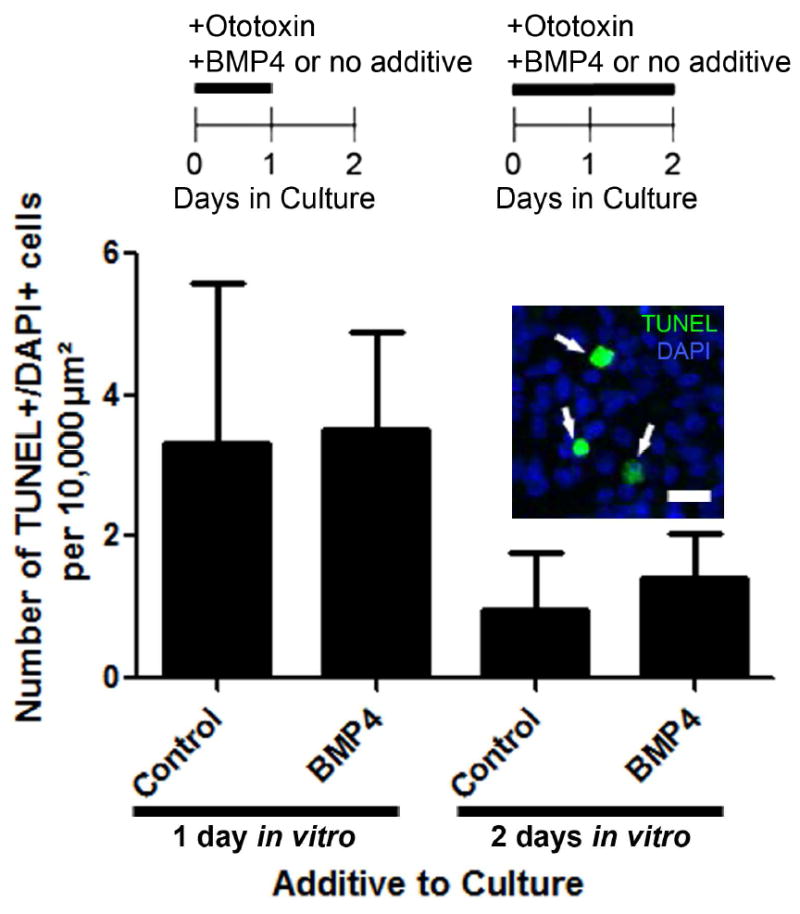

3.10. Treatment with BMP4 did not increase death of cells in the basilar papilla

It is possible that reductions in ATOH1 expression, hair cell differentiation, and dividing supporting cells in response BMP4 were due to damage or death of supporting cells or early hair cell precursors. To address this possibility, cochlear ducts were cultured with ototoxin for either 1 day or 2 days, with or without BMP4 (controls). Cochlear ducts were fixed and processed for TUNEL, which marks apoptotic cells, and for DAPI, which labels DNA.

TUNEL-positive cells were seen in each group (Fig. 5). We calculated the average density of TUNEL-positive particles in the mid-distal region of basilar papilla in each experimental group. We only counted TUNEL-positive particles that were DAPI-positive and therefore composed of DNA. Using two-way ANOVA, we found no significant effect of BMP4 treatment on numbers of TUNEL-positive particles (p = 0.6439, df = 1, f = 0.2231), but there was a significant effect of time (p = 0.0055, df = 1, f = 10.73), with higher numbers of TUNEL-positive particles at 1 day compared to 2 days in vitro. This result was probably attributable to a higher rate of hair cell death in the shorter culture, since ototoxins have rapid effects. Our results indicate that BMP4 does not increase the rate of apoptosis in either hair cells or supporting cells in culture.

Figure 5. BMP4 did not induce supporting cell apoptosis in cultured chicken basilar papillae.

As indicated in timelines at the top of the panel, cultured cochlear ducts were treated with ototoxin and either no additive or 10 ng/ml BMP4 for 1 or 2 days. Then, organs were fixed and labeled to detect the apoptotic cell marker, TUNEL. Graph shows the numbers of TUNEL-labeled cells per 10,000 μm2 of basilar papilla in each group. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. An example of TUNEL labeling in the mid-distal region of the basilar papilla is shown in the inserted image, with TUNEL in green and DAPI nuclear dye in blue. The numbers of basilar papillae included in analysis per group were: n=4 for 1 day plus ototoxin and BMP4 treatment; n=5 for 1 day plus ototoxin and no additive; n=5 for 2 days plus ototoxin and BMP4 treatment; n=4 for 2 days plus ototoxin and no additive. Scale bar = 10 μm.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. BMP4 antagonizes ATOH1 expression during hair cell regeneration

BMPs are secreted molecules that regulate cellular processes in many regions of the body, including the nervous system. We examined the role of BMP4 in regeneration of auditory hair cells in post-hatch chickens. We found that BMP4 transcripts are abundant in hair cells, and transcripts for BMP4 receptors and effectors (IDs) are abundant in supporting cells, the hair cell progenitors. Ototoxin kills hair cells, resulting in loss of BMP4 from the auditory epithelium. This loss of BMP4 coincides with when supporting cells normally upregulate ATOH1 and either divide or directly transdifferentiate to form new hair cells (Cafaro et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2012). ATOH1 is a positive regulator of hair cell development (Bermingham et al., 1999; Zheng and Gao, 2000) and regeneration (Shou et al., 2003; Kawamoto et al., 2003; Lewis et al., 2012). Addition of BMP4 to cultured cochlear ducts coincident with hair cell damage prevents upregulation of ATOH1 transcription and accumulation of ATOH1 protein in supporting cells and hair cells (Fig. 4). We did not determine how BMP4 attenuates ATOH1 expression, but some possible mechanisms are suggested by other studies. In chicken otocysts, BMP4 inhibits ATOH1 transcription, and this is, at least in part, executed by inhibitor of DNA-binding (ID) proteins. IDs are transcriptional co-factors that block activity of bHLH transcription factors such as ATOH1 (reviewed in Benezra et al., 1990; Wang and Baker, 2015). ID expression and activity are driven by BMP4 and other cellular signals (Miyazono and Miyazawa, 2002; Ying et al., 2003). IDs 1-3 are expressed in sensory regions of the chick otocyst (Kamaid et al., 2010). Treatment with BMP4 increases ID expression, and ID3 overexpression reduces ATOH1 transcripts and hair cell differentiation (Kamaid et al., 2010). Furthermore, prolonged expression of IDs in the developing organ of Corti attenuates hair cell differentiation (Jones et al., 2006). Although we did not test the function of IDs, we found that under normal conditions transcripts for BMP4 and ID3 are abundant in hair cells and supporting cells, respectively, and both transcripts are significantly reduced after damage, as ATOH1 increases (Figs. 1-3). These findings are consistent with a model by which BMP4 secreted from hair cells normally drives ID3 transcription in supporting cells, thereby attenuating ATOH1 transcription. Upon hair cell damage, loss of BMP4 would release ID3’s inhibition of ATOH1 transcription, allowing ATOH1 to accumulate in supporting cells and drive them to form new hair cells.

BMP4 signaling can also modulate levels of ATOH1 protein by stimulating its proteosomal degradation (Zhao et al., 2008). ATOH1 is highly expressed in cerebellar granule neuron precursors as they proliferate and migrate during development (Alder et al., 1996; Bermingham et al., 2001). Addition of BMP4 in vitro inhibits proliferation of cerebellar granule neuron precursors by degrading ATOH1 protein (Zhao et al., 2008). Future studies should determine if BMP4 stimulates ATOH1 degradation in supporting cells of the basilar papilla during normal conditions and during hair cell regeneration.

Our finding that exogenous BMP4 prevents ATOH1 upregulation after damage raises the possibility that BMP4 suppresses ATOH1 and maintains supporting cell quiescence under normal conditions, when hair cells are intact. With our current methods, we could not test this hypothesis, since hair cells begin to die when placed in culture, even in the absence of ototoxic drugs (Shang et al., 2010). It is interesting, however, that BMP4 is not expressed in hair cells in utricles of post-hatch chickens (Hawkins et al., 2003), in which hair cells throughout the organ undergo clearance and replacement throughout life. Assuming BMP4 has a conserved role in preventing supporting cell division and transdifferentiation across organs in the mature avian inner ear, its absence in the utricle would be advantageous, since abundance of this diffusible signaling molecule would antagonize hair cell replacement.

4.2. BMP4 antagonizes supporting cell division and hair cell regeneration in the basilar papilla

Addition of BMP4 to basilar papillae during hair cell damage in vitro blocks supporting cell division (Fig. 4). A similar effect with a similar BMP4 dose was reported recently by Jiang et al. (2018). The mechanism of this effect is not known. However, ATOH1 overexpression drives supporting cells to divide in the damaged chicken basilar papilla (Lewis et al., 2012) and in the developing organ of Corti (Kelly et al., 2012), which suggests BMP4 may regulate division by modulating ATOH1 levels. While one might predict that the BMP4 blocker NOG would have the opposite effect as BMP4 during early regeneration and decrease supporting cell division, this is not what we found. One interpretation of this finding is there is likely to be little or no BMP4 signaling to be blocked in the damaged region at this time, since BMP4 transcripts are extremely low (Figs. 1 and 3),

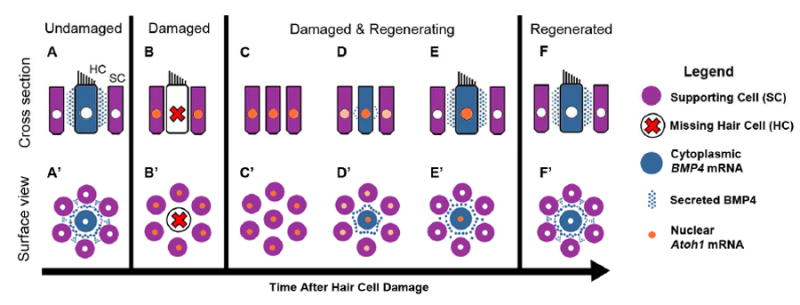

BMP4 addition to mature chicken cochlear ducts for longer periods (7 days) significantly reduces numbers of regenerated hair cells (Fig. 4). Since new hair cells emerge and express BMP4 mRNA as early as 4 days after damage, this finding suggests that nascent hair cells provide negative feedback to supporting cells or early hair cell precursors via BMP4, halting hair cell differentiation in some regions. In support of this interpretation, we found that NOG treatment does increase numbers of regenerated hair cells during this timeframe (Fig. 4). Based on our findings, we propose the following model for how BMP4 may regulate hair cell regeneration in damaged auditory organs in post-hatch chickens (Fig. 6). In the normal, undamaged condition (Fig. 6A,A’), hair cells secrete BMP4 that binds BMP receptors on nearby supporting cells. BMP4 signal transduction in supporting cells triggers transcription of IDs and other effectors (not shown) that maintain low transcripts for ATOH1. BMP4 may also induce ATOH1 degradation (see discussion below). Upon hair cell death, BMP4-mediated ATOH1 suppression is lost (Fig. 6B,B’), and ATOH1 transcription increases in supporting cells (Fig. 6C,C’). Supporting cells that accumulate ATOH1 either divide or transdifferentiate into hair cells (Fig. 6D,D’). When regenerated hair cells mature to the point of secreting BMP4, ATOH1 transcription in supporting cells or regenerated hair cells is reduced (Fig. 6E,E’). Once regenerated hair cells reach maturity, BMP4’s steady-state suppression of ATOH1 is reestablished (Fig 6F,F’).

Figure 6. Model for BMP4 effects on ATOH1 expression during hair cell regeneration in the chicken basilar papilla.

A-F represent cross-section views of hair cells (HC) and supporting cells (SC) under normal conditions (A) and at progressively later times after damage (B-F). A’-F’ represent surface views corresponding to A-F. Color coding for each cell type or molecule is indicated in the legend on the right. A,A’. Normal mature hair cells secrete BMP4, which binds receptors on nearby supporting cells and suppresses ATOH1 expression. B,B’. Hair cell loss reduces BMP4 signaling in the epithelium, allowing supporting cells to upregulate ATOH1. C-C’. Supporting cells expand into areas once occupied by hair cells and express ATOH1 at high levels. D,D’. Supporting cells have transdifferentiated into new hair cells. Both supporting cells and new hair cells continue to express ATOH1. Some regenerated hair cells secrete BMP4. E,E’. BMP4 derived from regenerated hair cells reduces ATOH1 expression in supporting cells. F,F’. ATOH1 is downregulated in hair cells and supporting cells once they mature. New hair cells secrete BMP4, maintaining low ATOH1 levels and supporting cell quiescence.

One puzzling finding is that there is a period when both ATOH1 and BMP4 transcripts are likely co-expressed in regenerated hair cells. This would occur between 4 and 8 days post-gentamicin (our findings here; Cafaro et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2012), but more expression studies, especially at the protein level, are required to accurately define when each protein would be active. Based on these observations, it is conceivable that BMP4 is released from regenerated hair cells and binds a BMP4 receptor on their surface, which based on our current understanding would antagonize ATOH1 levels. Mature hair cells express BMPR1a, BMPR1b, and BMPR2, but we did not examine when regenerated hair cells express these receptors. One possibility is that young hair cells do not express BMPRs and thus cannot transduce BMP4 signaling, allowing ATOH1 levels to remain high at critical early stages of differentiation. It is also possible that BMPRs are expressed in young hair cells but other pathways such as sonic hedgehog or Wnt antagonize BMP4 signaling within hair cells (Roberts et al., 1998; Baker et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2005). Sometime before 16 days post-gentamicin, ATOH1 becomes downregulated in the population of regenerated hair cells (Cafaro et al., 2007). At this point, ATOH1 downregulation could be regulated by autocrine BMP4 signaling that is established once new hair cells reach a certain point of maturation. These aspects of BMP4 signaling within hair cells remain to be tested.

We tested only one dose of BMP4 and Noggin for its effect on avian hair cell regeneration. We selected each dose because it fell within the range of doses employed in prior studies of chicken hair cell development (Pujades et al., 2006; Kamaid et al., 2010). However, different doses of each drug could have different effects upon hair cell regeneration. For instance, Pujades et al. (2006) found that 20 or 50 ng/ml BMP4 caused sensory progenitors in chick otocysts to stop dividing and to undergo apoptosis, while we found that 10 ng/ml BMP4 curtailed supporting cell division but did not promote apoptosis. Additional studies are required to determine if there are additional dose-dependent effects of BMP4 and Noggin during avian hair cell regeneration.

It is not possible to know which effects noted in our study are attributable solely to manipulation of BMP4 signaling. Other BMPs, such as BMP7, may be expressed in the mature basilar papilla. BMP7 transcripts were detected in embryonic day 16 supporting cells of chick BPs (Wu and Oh, 1996). To our knowledge, expression patterns for BMP family transcripts in post-hatch chicken basilar papillae have not been reported, and functions have not been tested. Nonetheless, BMP7 and other BMPs are modulated by Noggin, and addition of BMP4 to cultures could mimic signaling by these other ligands or alter dimerizations between BMP7 with BMP4 (reviewed in Guo and Wu, 2012). Further work is needed to hone our understanding of BMP signaling in the mature chicken BP, under normal conditions and during hair cell regeneration.

4.3. BMP4 has similar roles during hair cell development and regeneration in chickens

BMP4 regulates hair cell production during development. In otocysts of embryonic chickens, BMP4 transcripts are enriched in regions where sensory epithelia will form (Oh et al., 1996; Wu and Oh, 1996; Cole et al., 2000). Once basilar papillae differentiate, BMP4 expression becomes limited to hair cells (Oh et al., 1996). Treatment of cultured chicken otocysts with BMP4 reduces the number of cells that transcribe ATOH1 mRNA (presumed differentiating hair cells), while NOG has the opposite effect (Pujades et al., 2006). BMP4 also reduces numbers of dividing sensory progenitor cells in chicken otocysts (Pujades et al., 2006). For the most part, our observations are consistent Pujades et al. (2006) and distinct from Li et al. (2005), who found that BMP4 increases hair cell numbers in chick otocyst. However, BMP4 does not increase apoptotic cell death during avian hair cell regeneration (Fig. 5), as it does during avian hair cell development (Pujades et al., 2006).

BMP4 expression in the mature organ of Corti has not been well-characterized, and neither has the role of BMP4 during mammalian hair cell regeneration. During embryogenesis, BMP4 mRNA is not detected in the developing organ of Corti, but is instead expressed in non-sensory cells along the lateral edge of the sensory organ (Morsli et al., 1998; Ohyama et al., 2010). Treatment of embryonic cochleae with BMP4 results in higher numbers of outer hair cells (Puligilla et al., 2007). Suppression of BMP4 signaling causes cells in the lateral portion of the organ of Corti to express non-sensory markers (Ohyama et al., 2010) and prevents outer hair cell formation (Munnamalai and Fekete, 2016). These findings suggest BMP4 specifies lateral cells in the organ of Corti and promotes hair cell differentiation, which seems to contradict what has been reported during avian hair cell development and regeneration. These disparate findings may be due to true differences in the roles of BMP4 during development in birds and mammals. Or, they may have occurred because of variations in activation or attenuation of BMP4 signaling across studies. Future investigations are required to define if and how BMP4 signals to supporting cells after hair cell damage in the mature organ of Corti.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

We explored the role of BMP4 in regulation of hair cell regeneration in the auditory organ (basilar papilla) of post-hatch chickens.

BMP4 is expressed in hair cells, and its receptors and effectors are expressed in supporting cells.

BMP4 antagonizes ATOH1 accumulation in basilar papilla cells after hair cell damage.

BMP4 antagonizes supporting cell division and hair cell regeneration. The BMP4 antagonist NOG promotes hair cell regeneration.

BMP4 does not appear to induce apoptosis during avian auditory hair cell regeneration

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT.

BMP4’s negative regulation of Atoh1 and hair cell differentiation during embryogenesis has been described. However, no studies have reported a function for the diffusible protein BMP4 during hair cell regeneration in mature birds, mammals, or fish, to the best of our knowledge. We found in post-hatch chickens that BMP4 antagonizes hair cell regeneration, while inhibition of BMP4 signaling promotes regeneration. These observations help to elucidate the role of BMP4 during sensorineural tissue repair in mature animals and to raise awareness of signaling molecules that may modulate hair cell regeneration in other tissues and species.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Edwin Rubel, Julie Arenberg, and Richard Folsom for helpful discussions throughout the duration of the study. The authors extend their thanks and gratitude to Jialin Shang, Robin Gibson, and Irmina Haq for assistance with experiments. We also thank Glen MacDonald and Brandon Warren for help with digital imaging and data storage. We are grateful to David Raible, Lavinia Sheets, and Kirupa Suthakar for helpful comments prior to manuscript submission. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (F30 grant DC012228, RML; P30 grant DC04661, Edwin Rubel, PI; and R01 grant DC03696, JSS), the American Academy of Audiology (RML); the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (JJK); the Whitcraft Family (JSS); and the Hearing Restoration Project/Hearing Health Foundation (JSS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adler HJ, Raphael Y. New hair cells arise from supporting cell conversion in the acoustically damaged chick inner ear. Neurosci Lett. 1996;205:17–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson PJ, Wise AK, Flynn BO, Nayagam BA, Richardson RT. Hair cell regeneration after ATOH1 gene therapy in the cochlea of profoundly deaf adult guinea pigs. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e102077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker JC, Beddington RS, Harland RM. Wnt signaling in Xenopus embryos inhibits bmp4 expression and activates neural development. Genes Dev. 1999;13(23):3149–59. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.23.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benezra R, Davis RL, Lockshon D, Turner DL, Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bermingham NA, Hassan BA, Wang VY, Fernandez M, Banfi S, Bellen HJ, Fritzsch B, Zoghbi HY. Proprioceptor pathway development is dependent on Math1. Neuron. 2001;30(2):411–22. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bermingham NA, Hassan BA, Price SD, Vollrath MA, Ben-Arie N, Eatock RA, Bellen HJ, Lysakowski A, Zoghbi HY. Math1: an essential gene for the generation of inner ear hair cells. Science. 1999;284:1837–1841. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bermingham-McDonogh O, Rubel EW. Hair cell regeneration: Winging our way towards a sound future. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2003;13(1):199–26. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhave SA, Stone JS, Rubel EW, Coltrera MD. Cell cycle progression in gentamicin-damaged avian cochleas. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4618–4628. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04618.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brazil DP, Church RH, Surae S, Godson C, Martin F. BMP signalling: Agony and antagony in the family. Trends in Cell Biology. 2015;25(5):249–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cafaro J, Lee GS, Stone JS. Atoh1 expression defines activated progenitors and differentiating hair cells during avian hair cell regeneration. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:156–170. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai T, Seymour ML, Zhang H, Pereira FA, Groves AK. Conditional deletion of Atoh1 reveals distinct critical periods for survival and function of hair cells in the organ of Corti. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10110–10122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5606-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai T, Jen H-I, Kang H, Klisch TJ, Zoghbi HY, Groves AK. Characterization of the transcriptome of nascent hair cells and identification of direct targets of the Atoh1 transcription factor. J Neurosci. 2015;35:5870–5883. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5083-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chardin S, Romand R. Regeneration and mammalian auditory hair cells. Science. 1995;267:707–711. doi: 10.1126/science.7839151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen P, Johnson JE, Zoghbi HY, Segil N. The role of Math1 in inner ear development: Uncoupling the establishment of the sensory primordium from hair cell fate determination. Development. 2002;129:2495–2505. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chonko KT, Jahan I, Stone J, Wright MC, Fujiyama T, Hoshino M, Fritzsch B, Maricich SM. Atoh1 directs hair cell differentiation and survival in the late embryonic mouse inner ear. Dev Biol. 2013;381:401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cole LK, Le Roux I, Nunes F, Laufer E, Lewis J, Wu DK. Sensory organ generation in the chicken inner ear: contributions of bone morphogenetic protein 4, serrate1, and lunatic fringe. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424(3):509–20. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000828)424:3<509::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corwin JT, Cotanche DA. Regeneration of sensory hair cells after acoustic trauma. Science. 1988;240:1772–1774. doi: 10.1126/science.3381100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotanche DA. Regeneration of hair cell stereociliary bundles in the chick cochlea following severe acoustic trauma. Hear Res. 1987;30:181–195. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotanche DA, Kaiser CL. Hair cell fate decisions in cochlear development and regeneration. Hearing Research. 2010;266:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruz RM, Lambert PR, Rubel EW. Light microscopic evidence of hair cell regeneration after gentamicin toxicity in chick cochlea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:1058–1062. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1987.01860100036017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daudet N, Gibson R, Shang J, Bernard A, Lewis J, Stone J. Notch regulation of progenitor cell behavior in quiescent and regenerating auditory epithelium of mature birds. Dev Biol. 2009;326:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng J, Gao J, Li Y, Yang Y, Dang L, Ye Y, Deng J, Li A. BMP4 enhances foam cell formation by BMPR-2/Smad1/5/8 signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:5536–5552. doi: 10.3390/ijms15045536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forge A, Li L, Nevill G. Hair cell recovery in the vestibular sensory epithelia of mature guinea pigs. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998;397(1):69–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorący I, Safranow K, Dawid G, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Kaczmarczyk M, Gorący J, Loniewska B, Ciechanowicz A. Common genetic variants of the BMP4, BMPR1A, BMPR1B, and ACVR1 genes, left ventricular mass, and other parameters of the heart in newborns. Genet Test Mol Biomark. 2012;16:1309–1316. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo J, Wu G. The signaling and functions of heterodimeric bone morphogenetic proteins. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2012;23(1-2):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashino E, Salvi RJ. Changing spatial patterns of DNA replication in the noise-damaged chick cochlea. J Cell Sci. 1993;105(1):23–31. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasson T, Gillespie PG, Garcia JA, MacDonald RB, Zhao Y, Yee AG, Mooseker MS, Corey DP. Unconventional myosins in inner-ear sensory epithelia. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1287–1307. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkins RD, Bashiardes S, Helms CA, Hu L, Saccone NL, Warchol ME, Lovett M. Gene expression differences in quiescent versus regenerating hair cells of avian sensory epithelia: Implications for human hearing and balance disorders. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12(11):1261–1272. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henrique D, Adam J, Myat A, Chitnis A, Lewis J, Ish-Horowicz D. Expression of a Delta homologue in prospective neurons in the chick. Nature. 1995;375(6534):787–790. doi: 10.1038/375787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyer J, Kuhlman J, Afif E, Mikawa T. Optic cup morphogenesis requires pre-lens ectoderm but not lens differentiation. Developmental Biology. 2003;259(2):351–363. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh M, Chitnis AB. Expression of proneural and neurogenic genes in the zebrafish lateral line primordium correlates with selection of hair cell fate in neuromasts. Mech Dev. 2001;102:263–266. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janas JD, Cotanche DA, Rubel EW. Avian cochlear hair cell regeneration: stereological analyses of damage and recovery from a single high dose of gentamicin. Hearing Research. 1995;92(1–2):17–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang L, Xu J, Jin R, Bai H, Zhang M, Yang S, Zhang X, Zhang X, Han Z, Zeng S. Transcriptomic analysis of chicken cochleae after gentamicin damage and the involvement of four signaling pathways (Notch, FGF, Wnt and BMP) in hair cell regeneration. Hear Res. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones JM, Montcouquiol M, Dabdoub A, Woods C, Kelley MW. Inhibitors of differentiation and DNA binding (Ids) regulate Math1 and hair cell formation during the development of the organ of Corti. J Neurosci. 2006;26:550–558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3859-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamaid A, Neves J, Giráldez F. Id gene regulation and function in the prosensory domains of the chicken inner ear: a link between Bmp signaling and Atoh1. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11426–11434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2570-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawakami Y, Ishikawa T, Shimabara M, Tanda N, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Iwamoto M, Kuwana T, Ueki A, Noji S, Nohno T. BMP signaling during bone pattern determination in the developing limb. Development. 1996;122(11):3557–3566. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawamoto K, Ishimoto S-I, Minoda R, Brough DE, Raphael Y. Math1 gene transfer generates new cochlear hair cells in mature guinea pigs in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4395–4400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04395.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kee Y, Bronner-Fraser M. Temporally and spatially restricted expression of the helix-loop-helix transcriptional regulator Id1 during avian embryogenesis. Mechanisms of Development. 2001a;109(2):331–335. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kee Y, Bronner-Fraser M. The transcriptional regulator Id3 is expressed in cranial sensory placodes during early avian embryonic development. Mechanisms of Development. 2001b;109(2):337–340. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kee Y, Bronner-Fraser M. Id4 expression and its relationship to other Id genes during avian embryonic development. Mechanisms of Development. 2001c;109(2):341–345. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly MC, Chang Q, Pan A, Lin X, Chen P. Atoh1 Directs the Formation of Sensory Mosaics and Induces Cell Proliferation in the Postnatal Mammalian Cochlea In Vivo. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(19):6699–6710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5420-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis RM, Hume CR, Stone JS. Atoh1 expression and function during auditory hair cell regeneration in post-hatch chickens. Hearing Research. 2012;289(1-2):74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Corrales CE, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Liu H, Heller S. BMP4 signaling is involved in the generation of inner ear sensory epithelia. BMC Dev Biol. 2005;5(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munnamalai V, Fekete DM. Notch-Wnt-Bmp crosstalk regulates radial patterning in the mouse cochlea in a spatiotemporal manner. Development. 2016;143(21):4003–4015. doi: 10.1242/dev.139469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Millimaki BB, Sweet EM, Dhason MS, Riley BB. Zebrafish atoh1 genes: classic proneural activity in the inner ear and regulation by Fgf and Notch. Development. 2007;134:295–305. doi: 10.1242/dev.02734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem. 2010;147:35–51. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyazono K, Miyazawa K. Id: a target of BMP signaling. Science’s STKE : Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment. 2002;151:pe40. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.151.pe40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morsli H, Choo D, Ryan A, Johnson R, Wu DK. Development of the mouse inner ear and origin of its sensory organs. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3327–3335. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03327.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oh SH, Johnson R, Wu DK. Differential expression of bone morphogenetic proteins in the developing vestibular and auditory sensory organs. J Neurosci. 1996;16(20):6463–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06463.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohyama T, Basch ML, Mishina Y, Lyons KM, Segil N, Groves AK. BMP signaling is necessary for patterning the sensory and nonsensory regions of the developing mammalian cochlea. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15044–15051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan N, Jahan I, Kersigo J, Duncan JS, Kopecky B, Fritzsch B. A novel Atoh1 “self-terminating” mouse model reveals the necessity of proper Atoh1 level and duration for hair cell differentiation and viability. PloS One. 2012;7:e30358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pujades C, Kamaid A, Alsina B, Giraldez F. BMP-signaling regulates the generation of hair-cells. Dev Biol. 2006;292:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puligilla C, Feng F, Ishikawa K, Bertuzzi S, Dabdoub A, Griffith AJ, Fritzsch B, Kelley MW. Disruption of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 signaling results in defects in cellular differentiation, neuronal patterning, and hearing impairment. Developmental Dynamics. 2007;236(7):1905–1917. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberson DW, Alosi JA, Cotanche DA. Direct transdifferentiation gives rise to the earliest new hair cells in regenerating avian auditory epithelium. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:461–471. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberson DW, Rubel EW. Cell division in the gerbil cochlea after acoustic trauma. Am J Otol. 1994;15:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roberts DJ, Johnson RL, Burke AC, Nelson CE, Morgan BA, Tabin C. Sonic hedgehog is an endodermal signal inducing Bmp-4 and Hox genes during induction and regionalization of the chick hindgut. Development. 1995;121(10):3163–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roberts DJ, Smith DM, Goff DJ, Tabin CJ. Epithelial-mesenchymal signaling during the regionalization of the chick gut. Development. 1998;125:2791–2801. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryals BM, Rubel EW. Hair cell regeneration after acoustic trauma in adult Coturnix quail. Science. 1988;240:1774–1776. doi: 10.1126/science.3381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shang J, Cafaro J, Nehmer R, Stone J. Supporting cell division is not required for regeneration of auditory hair cells after ototoxic injury in vitro. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 2010;11(2):203–22. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0206-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shou J, Zheng JL, Gao WQ. Robust generation of new hair cells in the mature mammalian inner ear by adenoviral expression of Hath1. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;23:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sobkowicz HM, August BK, Slapnick SM. Cellular interactions as a response to injury in the organ of Corti in culture. J Int Dev Neurosci. 1997;15:463–485. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(96)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Staecker H, Schlecker C, Kraft S, Praetorius M, Hsu C, Brough DE. Optimizing atoh1-induced vestibular hair cell regeneration. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:5. doi: 10.1002/lary.24775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stone JS, Leaño SG, Baker LP, Rubel EW. Hair cell differentiation in chick cochlear epithelium after aminoglycoside toxicity: in vivo and in vitro observations. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6157–6174. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06157.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stone JS, Cotanche DA. Identification of the timing of S phase and the patterns of cell proliferation during hair cell regeneration in the chick cochlea. J Comp Neurol. 1994;341:50–67. doi: 10.1002/cne.903410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stone JS, Cotanche DA. Hair cell regeneration in the avian auditory epithelium. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:633–647. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072408js. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stone JS, Rubel EW. Delta1 expression during avian hair cell regeneration. Development. 1999;126:961–73. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stone JS, Rubel EW. Temporal, spatial, and morphologic features of hair cell regeneration in the avian basilar papilla. J Comp Neurol. 2000;417:1–16. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000131)417:1<1::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Wijk B, Moorman AFM, van den Hoff MJB. Role of bone morphogenetic proteins in cardiac differentiation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang L-H, Baker NE. E Proteins and ID Proteins: Helix-Loop-Helix Partners in Development and Disease. Developmental Cell. 2015;35(3):269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woods C, Montcouquiol M, Kelley MW. Math1 regulates development of the sensory epithelium in the mammalian cochlea. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1310–1318. doi: 10.1038/nn1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu DK, Oh SH. Sensory organ generation in the chick inner ear. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6454–6462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06454.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ying QL, Nichols J, Chambers I, Smith A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115(3):281–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Y, Yeh LK, Zhang S, Call M, Yuan Y, Yasumaga M, Kao WW, Liu CY. Wnt/β-catenin signaling modulates corneal epithelium stratification via inhibition of Bmp4 during mouse development. Development. 2015;142(19):3383–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.125393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao H, Ayrault O, Zindy F, Kim J-H, Roussel MF. Post-transcriptional down-regulation of Atoh1/Math1 by bone morphogenic proteins suppresses medulloblastoma development. Genes & Development. 2008;22(6):722–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.1636408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng JL, Gao WQ. Overexpression of Math1 induces robust production of extra hair cells in postnatal rat inner ears. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3(6):580–586. doi: 10.1038/75753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zou H, Wieser R, Massagué J, Niswander L. Distinct roles of type I bone morphogenetic protein receptors in the formation and differentiation of cartilage. Genes and Development. 1997;11(17):2191–2203. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.17.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.