Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a firmly incurable and progressive disease. The pathology of AD usually evolves from cognitive normal (CN), to mild cognitive impairment (MCI), to AD. The aim of this paper is to develop a Bayesian semiparametric mixed hidden Markov modeling (BSMHM2) framework to characterize disease pathology, identify hidden states corresponding to the diagnosed stages of cognitive decline, and examine the dynamic changes of potential risk factors associated with the CN-MCI-AD transition. The BSMHM2 framework consists of two major components. The first one is a state-dependent semiparametric regression for delineating the complex associations between clinical outcomes of interest and a set of prognostic biomarkers across neurodegenerative states. The second one is a parametric transition model, while accounting for potential covariate effects on the cross-state transition. The inter-individual and inter-process differences are taken into account via correlated random effects in both components. Based on the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative dataset, we are able to identify four states of AD pathology, corresponding to common diagnosed cognitive decline stages, including CN, early MCI, late MCI, and AD and examine the effects of hippocampus, age, gender, and APOE-ε4 on degeneration of cognitive function across the four cognitive states.

Keywords: Bayesian P-splines, Correlated random effects, Hidden Markov models, MCMC methods, Semiparametric models

1 Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease that usually starts slowly and worsens over time. The most common early symptom of AD is short-term memory loss, also referred to mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Patients at MCI state have high likelihood to transit to dementia or AD within a few years (Albert et al., 2011). Despite an increasing attention to its growing public threat, the cause of AD remains poorly understood. Thus, it is great interest to discovering or validating prognostic biomarkers that may identify subjects at great risk for future cognitive decline and investigating the functional effects of various biomarkers on the conversion from NC to AD.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study began in 2004 and it collected imaging, generic, clinical, and cognitive data from subjects under cognitive normal (CN) controls and subjects with MCI or AD in order to delineate the complex associations among various characteristics of the clinical spectrum of AD. The ADNI-1 recruited approximately 800 subjects according to its initial aim and has been extended by three follow-up studies, namely, ADNI-GO, ADNI-2, and ADNI-3. ANDI-1 subjects had an option to refuse follow-up monitoring in subsequent studies. More information on ADNI can be obtained in the official website (www.adni-info.org). Functional assessment questionnaire (FAQ), an assessment of abilities to function independently in daily life, is widely used to monitor the decline of cognitive ability over time. The FAQ scores of each subject were obtained at baseline and then every 6 months across 9 years multiple study phases. For this longitudinal study, several central questions are naturally raised as follows:

(i) How many hidden pathophysiological states exist in the progression of AD?

(ii) Which factors should contribute to the neuro-degenerative pathology from one state (e.g., MCI) to another (e.g., AD)?

(iii) Whether the identified risk factors are equally good predictors of cognitive decline at each state?

Given these questions, there is a particular need for the development of statistical models that delineate cognitive decline in terms of the pathophysiological states of AD.

Hidden Markov models (HMM) are well suited to the characterization of longitudinal data in terms of a set of hidden states (Cappé et al., 2005; Maruotti, 2011; Bartolucci et al., 2013). HMMs consist of two components: a transition model to describe the dynamic transition of hidden states and a conditional regression model to examine state-specific covariate effects on responses. Owing to their ability to simultaneously reveal the longitudinal association structure and dynamic heterogeneity of the observed process, HMMs and their variants have attracted significant attention from the medical, behavioral, social, environmental, and psychological sciences (Vermunt et al., 1999; Scott et al., 2005; Schmittmann et al., 2005; Bartolucci and Farcomeni, 2009; Bartolucci et al., 2013; Chow et al., 2013). In particular, HMMs have previously been applied to investigate diseases progression to identify latent pathophysiological states. For instance, Albert et al. (1994) used HMMs to analyze multiple sclerosis disease across relapse and remission states (see also Altman and Petkau, 2005; Altman, 2007). Ip et al. (2013) identified ten disable states on the basis of a 10-year follow-up study of late-life disability in elder adults, and examined the patterns and risk factors for transition among disable states. Song et al. (2016) revealed the dynamic change of treatment effectiveness in preventing cocaine use across three cocaine addiction states.

Despite the rapid development and wide applications of HMMs, existing literature has mainly focused on parametric HMMs, in which the forms of covariate effects on responses and on transition probabilities are pre-specified. One problem of parametric models is that they may be too restrictive to reflect correctly the reality because the complex relationships among variables are seldom known a priori, and a pre-specified parametric form tends to overlook the subtle pattern of a function. A more comprehensive analysis can be performed by incorporating nonparametric functions into HMMs so that the functional effects of interest can be discovered. To the best of our knowledge, however, such nonparametric modeling has not been introduced into the HMM framework.

In this study, we propose a Bayesian mixed semiparametric hidden Markov modeling (BMSHM2) framework to analyze the ADNI-I dataset. Similar to conventional HMMs, the proposed model consists of two major components. The first component is a state-dependent semiparametric regression to investigate the linear and nonlinear effects of covariates, such as hippocampus, age, gender, and APOE-ε4, on the clinical outcome of cognitive decline (e.g., FAQ score). The second component is a mixed continuation-ratio logit transition model to examine various covariate effects on the probabilities of transitioning among neurodenerative states. We introduce a random effect in both models in order to account for inter-individual differences and allow the random effects to be dependent by assigning a joint distribution for them. Such joint random effects enable the model to accommodate the situation where some omitted factors influence both the observed process and the hidden transition process (Wulfsohn and Tsiatis, 1997; Chi and Ibrahim, 2006). We develop a full Bayesian approach, along with Bayesian P-splines procedure and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, for statistical inference. As far as we know, no previous study has ever been conducted either on the proposed BMSHM2 or on Bayesian HMMs. Also, this paper is the first to investigate the neurodegenerative pathology of AD.

Section 2 defines BMSHM2 and discusses the related identifiability issues. Section 3 introduces the Bayesian inference procedure. Section 4 illustrates the use of BMSHM2 in the analysis of the ADNI dataset. Section 5 demonstrates the empirical performance of the proposed methodology through a simulation study. Section 6 discusses the findings obtained from the analysis of the ADNI dataset. Technical details are provided in the Appendix.

2 Model description

2.1 Questions of Interest for ADNI-1

Data used in this article were obtained from the ADNI-1 database launched in 2003. A total of n = 633 patients at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months (t = 1, …, 4) were considered in the analysis. We use the score of FAQ, denoted by yit, to characterize the cognitive function of subject i at occasion t. Moreover, we observe a r × 1 vector of discrete covariates, denoted by bit = (bit,1, …, bit,r)T, and a q × 1 vector of continuous covariates, denoted by xit = (xit,1, …, xit,q)T. The covariates of interest include gender (1 = male; 0 = female), apolipoprotein E-ε4 (APOE-ε4), hippocampus, and age at baseline, in which APOE-ε4 is a known genetic risk factor for AD and is coded as 0, 1, and 2, denoting the number of APOE-ε4 alleles, and hippocampal volume is divided by whole brain volume to account for the confounding effect of brain size. Thus, APOE-ε4 (=1, bit,1), APOE-ε4 (=2, bit,2), and gender (bit,3) are discrete, whereas hippocampus (xit,1) and age at baseline (xit,2) are continuous.

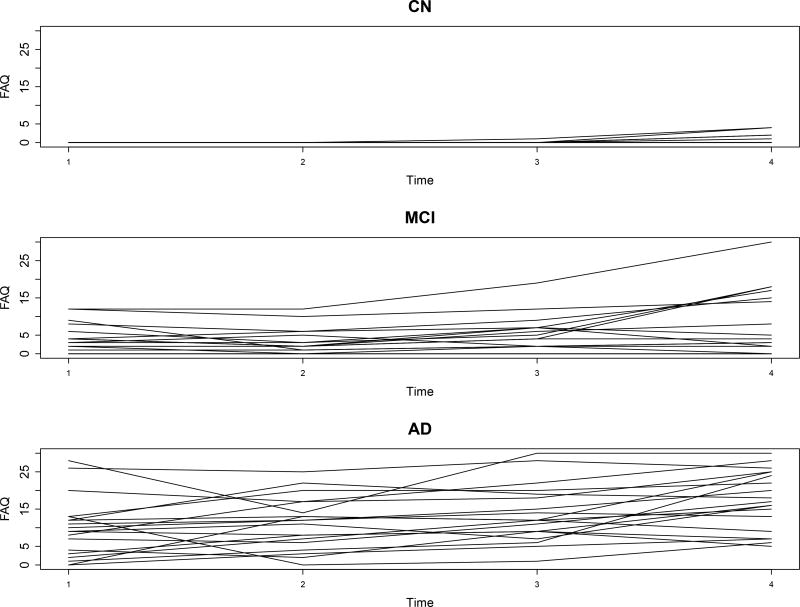

Several kinds of dependencies/heterogeneities are worthy of investigation. The first one is the dynamic heterogeneity across different groups. Figure 1 plots the individual trajectories of FAQ scores for 20 randomly selected samples, who were initially diagnosed as CN, MCI, and AD, respectively, at baseline. The cognitive decline patterns are apparently distinct over the groups, suggesting at least three (and probably more) distinct neurodegenerative states existent underlying the observations of FAQ score. The second one is the dependency of FAQ score on potential covariates, such as hippocampus, age at baseline, APOE-ε4, and gender. The third one is the serial dependency of the longitudinal observations, owing to relative persistence of neurodegenerative states. The last one is the heterogeneity caused by the existence of some omitted clinical or genetic indicators that influence both cognitive decline and its underlying transition. The BMSHM2 described below perfectly accommodates all these features.

Figure 1.

ADNI-1 data analysis results: individual trajectories of FAQ scores for 20 randomly selective samples whose baseline states are CN, MCI, and AD, respectively.

2.2 Model Setup

The BMSHM2 consists of two major components, including a conditional seminparametric regression model and a continuation-ratio logit transition model, as detailed below.

2.2.1 Conditional semiparametric regression model

Let yit with subject i = 1, …, n at t = 1, …, T be the observation process. The hidden state process, Zit, which takes values in {1, …, S}, is assumed to follow a first-order Markov chain. Given the hidden state Zit = s, the conditional semiparametric regression model is defined as follows:

| (1) |

where μs is a state-specific intercept, γs = (γ1, …, γr) is a state-specific vector of fixed effect of discrete covariates, fsj(·)s are state-specific unknown smoothing functions, bit = (bit,1, …, bit,r)T and xit = (xit,1, …, xit,q)T are r × 1 vector of discrete covariates and q × 1 vector of continuous covariates respectively, wi1 is a subject-specific random effect, δit is a random residual independent of yit, and [δit|Zit = s] ~ N[0, ψs].

The conditional model defined by (1) extends the parametric regression to allow the additive nonparametric functions of covariates, so that the functional effects of interest can be discovered. Such nonparametric modeling provides great flexibility in fitting nonlinear effects whose forms need not be specified a priori. When used as an exploratory tool, the proposed model is able to help users to visually examine and interpret the functional effects of potential predictors on the response of interest. Moreover, the subject-specific random effect wi1 permits additional dependencies elicited from other sources and thus avoids a large number of hidden states caused by possible residual correlation among responses.

2.2.2 Continuation-ratio logit transition model

Let pitus denote the transition probability from state Zi,t−1 = u at occasion t − 1 to state Zit = s at occasion t for individual i. Based on the assumption of the first-order Markov chain, we have

| (2) |

The initial distribution of Zi1 is assumed to be a multinomial with probabilities (τ1, …, τS)T such that τs ≥ 0 and . The distribution of is then fully determined by the transition probabilities and the distribution of the initial state.

In the study of disease progression, the hidden states can often be naturally ranked (e.g., CN, MCI, and AD can be ranked from the best to the worst cognitive condition). Thus, we assume that the hidden states {1, …, S} are ordered and ϑitus = P(Zit = s|Zit ≥ s, Zi,t−1 = u). Then, the transition across the ordered states can be described by continuation logits as follows: For t = 2, …, T, s = 1, …, S − 1, and u = 1, …, S,

| (3) |

The parameterization in (3) is intended to facilitate the interpretation of transition to a state rather than to a better one. To examine the effects of potential predictors on the transition probabilities, we consider a continuation-ratio logit transition model as follows:

| (4) |

where ζus is a state-specific intercept, is the vector of covariates defined in (1), α is a (q + r) × 1 vector of regression coefficients that can be interpreted as conditional log odds ratios in a logistic regression, wi2 is a subject-specific random effect that is distinct from but correlated with wi1, and wi = (wi1, wi2)T is assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution N(0, Φ). Similar to the proportional assumption in a cumulative logit model, α in (4) is assumed to be independent of u and s in order to maintain the order of the hidden states and avoid a tedious transition model, in which every transition elicits a set of parameters for all possible states of origination and destination. This outcome, in turn, greatly reduces the complexity and enhances the interpretability of the transition model.

Notably, random effects wi1 and wi2 play different roles in the conditional and transition models. While wi1 in conditional model (1) relaxes the assumption that observations {yit; i = 1, …, n, t = 1, …, T} are conditionally independent given the hidden state Zit = s, wi2 in transitional model (4) releases the assumption that hidden process Zit is Markovian. Unlike the existing literature that usually treats wi1 and wi2 separately, we accommodate their possible correlation by assigning a joint distribution for wi = (wi1, wi2)T. Consequently, the possible correlation between the heterogeneities existent within the two stochastic processes can be appropriately addressed and examined through the covariance matrix Φ.

2.3 Model identification

The proposed model is not identifiable because of the following two model indeterminacies. The first is caused by the additive nonparametric functions involved in (1), in which each unknown function is not identifiable up to a constant. To address this problem, we need to impose constraints on the unknown functions to enforce their integrations in the ranges of predictors to zero (Panagiotelis and Smith, 2008; Song and Lu, 2010) as follows:

| (5) |

where 𝒳j is the support of xj. The other model determinacy is the label switching problem elicited by the invariance of the likelihood function to a random permutation of the state labels, which results in a multi-modal posterior under a symmetric prior specification. We follow Frühwirth-Schnatter (2001) to conduct a permutation sampler to address this issue.

3 Bayesian Inference

3.1 Nonparametric modeling

The first critical issue in the Bayesian analysis of the proposed model is to estimate the nonparametric functions involved in (1). We consider the use of Bayesian P-splines (Berry et al., 2002; Lang and Brezger, 2004; Fahrmeir and Raach, 2007). The basic idea is to estimate the unknown smoothing functions through a sum of B-splines basis functions (De Boor, 2001) given a large number of knots in the domains of predictors. Specifically, fsj(xit,j), the functional effect of the jth covariate at state s for subject i at time t, can be approximated as follows:

| (6) |

where L is the number of splines determined by the number of knots, βsj = (βsj,1, …, βsj,L)T is the vector of the unknown parameters, B(·)s’ are cubic B-splines basis functions, and B(xit,j) = (B1(xit,j), …, BL(xit,j))T. Usually, L taking a value from 10 to 30 provides sufficient flexibility in fitting most smooth functions.

One problem of applying (6) to approximate an unknown smooth function is the over-fitting caused by the use of a large number of knots. Eilers and Marx (1996) suggested the penalization of the coefficients of adjacent B-splines basis functions to prevent the overfitting. Such penalization can be implemented in the Bayesian framework by applying random walk priors to βsj (Lang and Brezger, 2004; Fahrmeir and Raach, 2007; Song and Lu, 2010).

3.2 Prior distributions

We assign a truncated Gaussian priors for βsj as follows:

| (7) |

where νsj is a smoothing parameter for controlling the amount of penalty, Ksj is a penalty matrix derived according to the random walk penalties proposed, Lsj is the rank of Ksj, 1ns is an ns × 1 vector with all elements equal to 1, ns is the sample size at state s, Bsj is the sub-matrix of Bj = [Bl(xit,j)]nT×L without the rows where Zit ≠ s, and the truncation term incorporates the identifiability constraint (5) into the splines approximation (6).

For the smoothing parameters νsj, we assign a highly dispersed but proper inverse gamma prior as follows:

| (8) |

where ν1 and ν2 are hyperparameters whose values are pre-specified. A common choice for these hyperparameters is ν1 = 1 and ν2 is small (Fahrmeir and Raach, 2007; Song and Lu, 2010). We set ν1 = 1 and ν2 = 0.005 in the present study.

For the parameters involved in conditional model (1), conjugate-type priors are assigned as follows: for s = 1, …, S,

| (9) |

where μs0, , γs0, Σs0, α̃s0, β̃s0, R0, and ρ0 are hyperparameters with preassigned values.

Finally, for the parameters involved in transition model (4), we consider the following Gaussian priors:

| (10) |

where ζus0, , α0, Hα0, τs0, and are hyperparameters with preassigned values.

3.3 Posterior computation

Let yi = (yi1, …, yiT)T, Y = (y1, …, yN), D = (d11, …, dNT), Zi = (Zi1, …, ZiT)T, Z = (Z1, …, ZN), W = (w1, …, wN), and θ be the vector that includes all the unknown parameters in the proposed model. The complete-data log-likelihood function that is used to derive the posterior distributions and compute the model selection criterion is given by

| (11) |

where

| (12) |

with aitus = ζus + αTdit + wi2.

The Bayesian estimate of θ is obtained by drawing samples from p(θ|Y), which is intractable because of the existence of latent states and random effects. We instead work on p(θ, Z, W|Y) and use a Gibbs sampler to implement the posterior simulation. Owing to the nonlinearity of the continuation-logit transition model and the existence of the nonparametric functions in the conditional regression, some full conditional distributions, especially those related to the transition model, have complex forms. MCMC methods, such as the forward filtering and backward sampling algorithm (Cappé et al., 2005) and the Metropolis-Hastings (MH) algorithm (Metropolis et al., 1953; Hastings, 1970), are employed to sample from them. The details are provided in the Appendix.

With the use of posterior samples, the hidden states can be estimated as follows:

| (13) |

where denotes the latent allocation of yit at the mth iteration, and is the posterior mean of the latent allocations of yit drawn from the MCMC iterations.

3.4 Determination of the number of hidden states

In the applications of BMSHM2 to the ADNI dataset, the states of the Markov chain can often naturally be interpreted as proxies for the neurodegenerative states, although a one-to-one correspondence between nominal HMM states and the clinical cognitive stages diagnosed by doctors is unnecessary. In this regard, a relevant question is how to determine the number of hidden states in the analysis of ADNI data. We propose the use of a modified deviance information criteria (DIC) to determine the number of hidden states and choose a plausible model for the ADNI data analysis.

The modified DIC, which was developed by Celeux et al. (2006) for model comparison in the presence of incomplete data, is defined as follows:

| (14) |

where log p(Y, W, Z|θ) is the complete-data log-likelihood function shown in (11). The expectations involved in (14) can be approximated using the posterior samples collected through MCMC methods (Celeux et al., 2006). In model selection, the model with the smallest value of DIC is selected.

4 Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Data Analysis

4.1 Data description

The ADNI was launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), private pharmaceutical companies and nonprofit organizations, as a $60 million, 5-year public private partnership. The initial goal of ADNI was to recruit 800 adults, aged 55 to 90, to participate in the research – approximately 200 cognitively normal older individuals to be followed for 3 years, 400 people with MCI to be followed for 3 years, and 200 people with early AD to be followed for 2 years.

We focused on 633 subjects who were all followed up at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months. For each subject, we included his/her clinical, genetic, and imaging variables at the four time points. The clinical characteristics include gender (0 = male; 1 = female), age at baseline, and FAQ score. The FAQ score is an assessment of abilities to function independently in daily life and is widely used to monitor the decline of cognitive ability over time. The genetic variables include APOE gene because mutations in APOE raise the risk of progression from amnestic MCI to AD (Petersen et al., 2005). The APOE SNPs, rs429358 and rs7412 were separately genotyped in ADNI-1. These two SNPs together define a 3-allele haplotype, namely, the ε2, ε3, and ε4 variants. Among these variants, APOE-ε4 has been identified as a risk factor for early onset of AD (e.g., Okuizumi et al., 1994). Thus, we considered the presence of APOE-ε4 as a covariate in this analysis. APOE-ε4 is coded as 0, 1, and 2, denoting the number of APOE-ε4 alleles. Furthermore, the logarithm of the ratio of hippocampal volume over whole brain volume was included as a covariate because published reports (Kesslak, Nalcioglu and Cotman, 1991; Jack et al., 1992; Dickerson and Wolk, 2013) revealed that the atrophy of the hippocampal formation was a significant diagnostic marker of clinical dementia. Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of the aforementioned variables for the samples under consideration. Males account for about 56.2% in the samples. Mean values of patients’ age (in year), adjusted hippocampal volume, and corresponding FAQ score are 73.0, −5.0, and 4.1, respectively. 34.6% patients carry one APOE-ε4 allele while only 9.8% carry two APOE-ε4 alleles.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study samples in the ADNI-1 dataset

| Mean Age (in years) | 73.0(6.9) |

| Gender (Male percentage) | 56.2% |

| Mean log(hippocampus/whole brain volume) | −5.0(0.2) |

| Mean FAQ score | 4.1(6.5) |

| One APOE-ε4 allele carriers | 34.6% |

| Two APOE-ε4 alleles carriers | 9.8% |

The numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.

4.2 Data analysis

The aims of this ADNI data analysis are (I) to identify the hidden states of the neurodegenerative pathology on the basis of 633 patients enrolled in the ADNI-1, (II) to reveal a set of potential covariates that influence the between-states transition, and (III) to investigate the linear and/or functional covariate effects on cognitive decline across the hidden states of the AD progression.

We fitted BMSHM2 with the FAQ score as the response yit, the clinical and genetic variables, gender and APOE-ε4, as covariates in bit, and hippocampus and age at baseline as covariates in xit. Three continuous variables, FAQ score, hippocampus, and age, were standardized prior to analysis. We first determined the number of hidden states. We considered five competing models Mk, k = 1, …, 5, where Mk represents a BMSHM2 with k states. A total of 24 equidistant knots were used to construct cubic P-splines, and the second-order random walk penalties were used for the Bayesian P-splines to estimate the unknown smooth functions. Given the lack of prior information, we assign the hyperparameters in (9) and (10) to reflect vague prior information as follows: μs0 = ζus0 = τs0 = 0, , α̃s0 = 9, β̃s0 = 4, ρ0 = 7, R0 = 4I2, α0 and γs0 is a vector with all elements being zero, Hα = I5 and Σs0 = I3 where Ir is a r-dimensional identity matrix. We used the random permutation sampler to search for a suitable identifiability constraint to solve the label switching problem. The MCMC algorithm converged within 2,000 iterations for all competing models. We collected a total of 10,000 observations after discarding 2,000 burn-in iterations to calculate DIC. The DIC values corresponding to M1 to M5 were 20,175, 1,823, 1,001, 950, and 1615, respectively. Thus, the four-state model M4 was selected.

To examine the necessity of the random effects in the proposed model, we considered another competing model MN: a four-state BMSHM2 without random effects. The DIC value for MN is 1,122, which suggests an evident advantage of the proposed mixed effect model in the presence of high dependency/heterogeneity in longitudinal observations. Thus, M4 was selected for the subsequent analysis. The estimation results obtained under M4 are reported in Table 2 (parametric part) and Figure 2 (nonparametric part).

Table 2.

ADNI-1 data analysis results: parameter estimation results.

| Parameters in conditional regression model | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| State 1 | State 2 | State 3 | State 4 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Par. | Est | SE | Par. | Est | SE | Par. | Est | SE | Par. | Est | SE |

|

| |||||||||||

| μ1 | −0.556 | 0.013 | μ2 | 0.029 | 0.114 | μ3 | 1.108 | 0.134 | μ4 | 2.494 | 0.127 |

| ψ1 | 0.013 | 0.001 | ψ2 | 0.135 | 0.019 | ψ3 | 0.187 | 0.025 | ψ4 | 0.397 | 0.057 |

| γ11 | 0.016 | 0.018 | γ21 | 0.163 | 0.098 | γ31 | 0.102 | 0.131 | γ41 | 0.443 | 0.140 |

| γ12 | 0.079 | 0.033 | γ22 | 0.260 | 0.132 | γ32 | 0.307 | 0.157 | γ42 | 0.407 | 0.193 |

| γ13 | 0.011 | 0.015 | γ23 | 0.038 | 0.100 | γ33 | −0.252 | 0.142 | γ43 | −0.557 | 0.137 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Parameters in probability transition model | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Par. | Est | SE | Par. | Est | SE | Par. | Est | SE | Par. | Est | SE |

|

| |||||||||||

| τ1 | 0.938 | 0.110 | τ2 | −0.303 | 0.373 | τ3 | 1.132 | 0.330 | α1 | 0.500 | 0.080 |

| α2 | 0.035 | 0.067 | α3 | −0.342 | 0.141 | α4 | −0.728 | 0.230 | α5 | 0.085 | 0.162 |

| ζ11 | 2.477 | 0.158 | ζ21 | −1.714 | 0.342 | ζ31 | −3.244 | 0.508 | ζ41 | −3.252 | 0.512 |

| ζ12 | 2.540 | 0.493 | ζ22 | 1.198 | 0.411 | ζ32 | −1.661 | 0.479 | ζ42 | −3.114 | 0.525 |

| ζ13 | 1.877 | 0.779 | ζ23 | 2.618 | 0.445 | ζ33 | 1.298 | 0.307 | ζ43 | −1.845 | 0.432 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Covariance matrix of random effects | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Par. | Est | SE | Par. | Est | SE | Par. | Est | SE | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| φ11 | 0.024 | 0.002 | φ22 | 0.223 | 0.051 | φ12 | −0.007 | 0.006 | |||

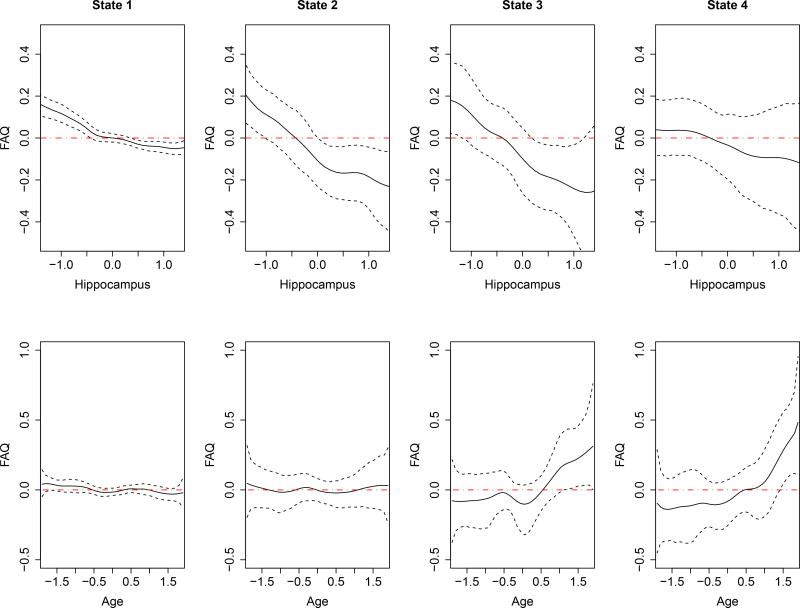

Figure 2.

ADNI-1 data analysis results: estimates of the unknown smooth functions. The solid curves represent the pointwise mean curves, and the dashed curves represent the 2.5%-and 97.5%- pointwise quantiles. line y = 0 has been shown on each picture by red dot-dash to illustrate the range of significant effect for each variable.

We have the following observations. First, μ1, μ2, μ3, and μ4 are ranked in an ascending order, indicating that patients in state 1 got the lowest score of FAQ, whereas those in state 4 got the highest. That is, patients’ ability to function independently in daily life steadily deteriorated from state 1 to state 4. According to the existing literature (Kantarci et al., 2013), state 1 to state 4 can be explained as cognitive normal (CN), early mild cognitive impairment (EMCI), late mild cognitive impairment (LMCI), and AD, respectively.

Second, the functional effect of hippocampus on FAQ exhibits a descending trend as hippocampus grows regardless of states. Specifically, in CN state, people with bigger hippocampus volume tend to have slightly better memory. This finding is in line with the common sense that hippocampus plays an important role in the consolidation of information from short-term memory to long-term memory. In EMCI and LMCI states, the descending trend of the functional effect of hippocampus on FAQ becomes much more pronounced. This result implies that atrophy in hippocampus increasingly impaires patients’ cognitive ability. The published reports (e.g., Dickerson and Wolk, 2013; Kesslak, Nalcioglu and Cotman, 1991; Jack et al., 1992) also indicate that the volume loss of the hippocampus is greatly associated with clinical dementia. In AD state, the effect of hippocampal volume on FAQ is not significant because patients’ cognitive ability and memory have already been damaged by serious hippocampus atrophy.

Third, the effect of age on FAQ is nonsignificant in CN and EMCI states, implying that for those who have cognitive normal function or undergo only EMCI, age may not be a decisive factor for the reduction of cognitive ability. On the contrary, age exhibits nonlinear effects on FAQ in LMCI and AD states. The age effect is nonsignificant for relatively young patients but becomes significantly positive for elderly patients (say, over 85 years old). The positive effect increases with age and gets an even sharper rise in AD state. Such age effect was also discovered by previous studies (e.g. Gao et al., 1998; Lindsay et al., 2002).

Fourth, as for the fixed effects of discrete variables, a significantly negative effect of gender on FAQ appears in state 4, which means that male AD patients are in a better condition than females in terms of independent abilities. The two APOE-ε4 alleles (bit,1 and bit,2) have significantly positive effects on FAQ in state 4 and bit,1 also has a slightly positive effect on FAQ in other states. This finding agrees with the newly published clinical research output that the presence of ε4 alleles in the APOE gene is the only genetic variant broadly accepted as increasing risk for late-onset AD dementia (Albert et al., 2011).

Fifth, in the transition model, hippocampus positively affects the probability of transitioning from a state to a better one, indicating that controlling loss of hippocampal volume would be beneficial to prevent the deterioration of cognitive ability. Similar to previous studies (e.g., Lee et al., 2015), APOE-ε4 alleles have negative effects on the probability of transitioning from a state to a better one, reconfirming that APOE-ε4 alleles are important risk factors for the development of AD.

Sixth, the variances of the two random effects are significant, reconfirming the necessity of the random effects proposed. However, the corvariance between the two random effects is nonsignificant, showing that some omitted clinical or genetic indicators influenced outcomes of the observation process or probabilities of the transition process but did not affect the two processes simultaneously.

Moreover, we estimated the hidden states of all patients at four time points based on Equation (13). Around 98% posterior transition patterns are from a state to a severer one, which is in line with the common knowledge of irreversibility of AD. Table 3 reports patients’ estimated hidden states and their diagnosed status by doctors. For CN, LMCI, and AD states, a majority of the estimated states are consistent with those diagnosed by doctors. For EMCI state, however, 835 (67%) EMCI patients diagnosed by doctors were classified into CN state by our procedure. Such vague demarcation between CN and EMCI was also found and discussed in the literature (e.g., Petersen, 2004).

Table 3.

ADNI-1 data analysis results: comparison of estimated hidden states and diagnosis status

| Estimates | CN | EMCI | LMCI | AD | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| CN | 840 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 862 | |

| EMCI | 835 | 232 | 148 | 28 | 1243 | |

| LMCI | 9 | 21 | 39 | 21 | 90 | |

| AD | 23 | 49 | 106 | 159 | 337 | |

| Total | 1707 | 323 | 294 | 208 | 2532 | |

5 Simulation Study

We conduct Monte Carlo simulations to assess the empirical performance of the proposed method in estimation of the nonparametric functions and model parameters.

5.1 Model setup

We consider a BMSHM2 with four hidden states (S = 4), a continuous response yit, three discrete covariates (r = 3), and two continuous covariates (q = 2) to mimic the scenario of the ADNI study. For i = 1, …, 700 and t = 1, …, 9, bit,1, bit,2, and bit,3 are all generated from the Bernoulli distribution with the probability of success 0.5, and xit,1 and xit,2 are generated from U (−1, 1) and N (0, 1), respectively. The conditional model is defined as

| (15) |

where f11(xit,1) = −1.305+exp(xit,1), f12(xit,2) = 0.55+sin(1.5xit,2)+xit,2, f21(xit,1) = 0.06−log((1 + xit,1)/(1 − xit,1)), , f31(xit,1) = −0.05 − 0.8xit,1, f32(xit,2) = −0.275 + cos(2xit,2) + 0.5xit,2, and f42(xit,2) = −0.85 + 1.5xit,2.

The transition model is defined as

| (16) |

The true population values of the unknown parameters are set as μ = (μ1, μ2, μ3, μ4) = (−5, −1, 3, 7), τ = (τ1, τ2, τ3, τ4) = (0.27, 0.27, 0.23, 0.23), ζ11 = ζ21 = ζ31 = ζ41 = −1, ζ12 = ζ22 = ζ32 = ζ42 = −1/2, ζ13 = ζ23 = ζ33 = ζ43 = 1/2, γ1 = (γ11, γ12, γ13) = (−1, 0.5, 0.5), γ2 = (γ21, γ22, γ23) = (1, 1, 0.5), γ3 = (γ31, γ32, γ33) = (−0.5, −0.5, −0.5), γ4 = (γ41, γ42, γ43) = (0.5, −1, −1), α = (α1, α2, α3, α4, α5)T = (1, −1, −0.5, 0.5, 1), ψ = (ψ1, ψ2, ψ3, ψ4) = (1, 0.64, 0.36, 0.25), and Φ is a correlation matrix with off diagonal elements −0.5. Based on the above setup, we simulate 100 datasets for analysis.

5.2 Simulation results

We used a total of 24 equidistant knots to construct the cubic B-splines of the covariates. Again, the second-order random walk penalties were used for the Bayesian P-splines to estimate the unknown smooth functions. The prior inputs in (9) and (10) were assigned as follows: μs0 = ζus0 = τs0 = 0, , α̃s0 = 9, β̃s0 = 4, ρ0 = 7, R0 = 4I2, α0 and γs0 are vectors with all elements being zero, Hα = I5 and Σs0 = I3, where Ir is a r × r identity matrix. We conducted a few test runs to decide the number of burn-in iterations required for convergence and found that the MCMC algorithm converged within 2,000 iterations. Therefore, we obtain Bayesian results using 5,000 observations after discarding 2,000 burn-in iterations. The performance of the Bayesian estimates is assessed through the bias (BIAS) and the root mean square errors (RMSE) between the Bayesian estimates and the true population values of the parameters.

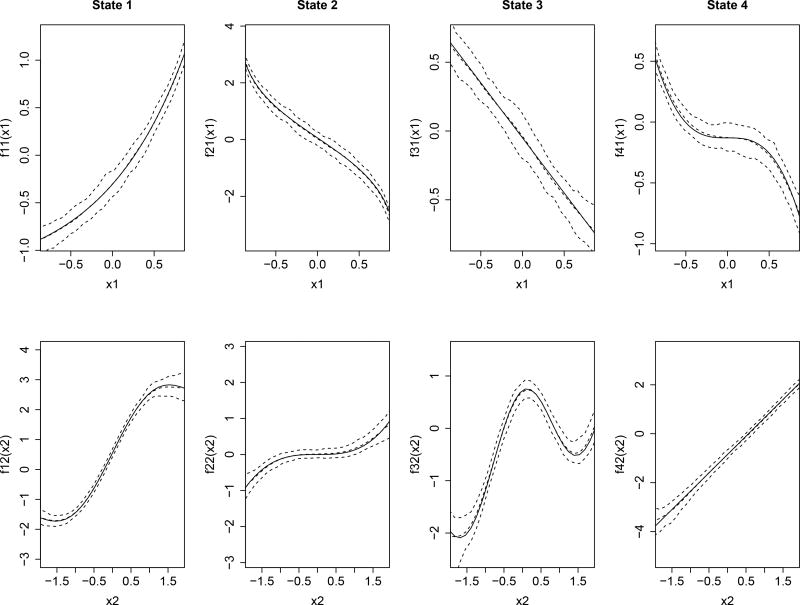

Table 4 summarizes the result of parameter estimation based on the 100 datasets. The BIAS and RMSE for most of the parameters are close to zero, indicating a satisfactory performance of Bayesian estimation regarding the parametric part. Figure 3 depicts the averages of the pointwise posterior means of the nonparametric functions, along with their 2.5%- and 97.5%- pointwise quantiles. The posterior means of the nonparametric functions are close to their true curves and all the ranges of the two pointwise quantiles are relatively small, indicating that the estimated functions can correctly recover the true functional relationships between the response and covariates. In this simulation, the average of the correct classification rates calculated through Equation (13) based on the 100 datasets is 91%. Considering the complexity of proposed model, this result is satisfactory.

Table 4.

Bayesian estimates of the parameters in the simulation study.

| Parameters in conditional regression model | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| State 1 | State 2 | State 3 | State 4 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Par. | Bias | RMSE | Par. | Bias | RMSE | Par. | Bias | RMSE | Par. | Bias | RMSE |

|

| |||||||||||

| μ1 | 0.010 | 0.098 | μ2 | 0.024 | 0.115 | μ3 | −0.046 | 0.195 | μ4 | −0.006 | 0.106 |

| ψ1 | −0.006 | 0.042 | ψ2 | 0.011 | 0.047 | ψ3 | 0.003 | 0.044 | ψ4 | 0.016 | 0.028 |

| γ11 | −0.002 | 0.105 | γ21 | −0.045 | 0.188 | γ31 | 0.025 | 0.147 | γ41 | −0.020 | 0.112 |

| γ12 | 0.002 | 0.091 | γ22 | −0.022 | 0.126 | γ32 | 0.030 | 0.168 | γ42 | 0.018 | 0.089 |

| γ13 | −0.013 | 0.090 | γ23 | −0.013 | 0.098 | γ33 | 0.026 | 0.126 | γ43 | 0.002 | 0.093 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Parameters in probability transition model | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Par. | Bias | RMSE | Par. | Bias | RMSE | Par. | Bias | RMSE | Par. | Bias | RMSE |

|

| |||||||||||

| τ1 | 0.008 | 0.137 | τ2 | −0.030 | 0.187 | τ3 | −0.048 | 0.236 | α1 | 0.007 | 0.068 |

| α2 | 0.010 | 0.064 | α3 | −0.024 | 0.103 | α4 | −0.011 | 0.122 | α5 | −0.029 | 0.112 |

| ζ11 | 0.040 | 0.125 | ζ21 | 0.042 | 0.132 | ζ31 | 0.034 | 0.120 | ζ41 | 0.035 | 0.131 |

| ζ12 | 0.050 | 0.168 | ζ22 | 0.031 | 0.156 | ζ32 | 0.037 | 0.162 | ζ42 | 0.034 | 0.167 |

| ζ13 | −0.034 | 0.197 | ζ23 | −0.032 | 0.195 | ζ33 | −0.027 | 0.186 | ζ43 | −0.032 | 0.197 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Covariance matrix of random effects | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Par. | Bias | RMSE | Par. | Bias | RMSE | Par. | Bias | RMSE | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| φ11 | 0.004 | 0.066 | φ22 | 0.017 | 0.161 | φ12 | 0.001 | 0.067 | |||

Figure 3.

Estimates of the unknown smooth functions in the simulation study: The solid curves represent the true curves, and the dashed curves represent the estimated posterior means and the 2.5%- and 97.5%- pointwise quantiles based on 100 replications, respectively.

To reveal the sensitivity of the Bayesian estimates to the input of priors, we disturbed the prior inputs as follows: μs0 = ζus0 = τs0 = 2, , α̃s0 = 3, β̃s0 = 2, ρ0 = 4, R0 = 2I2, α0 and γs0 are vectors with all elements being two, Hα = 2I5 and Σs0 = 2I3. The obtained results are similar and not reported.

6 Discussion

The BMSHM2 was developed and successfully applied to the ADNI data analysis. Although HMMs and their variants have already been extensively used for longitudinal data analysis, a majority of applications restrict analysis in a parametric framework. Nonetheless, examples of using HMMs to classify and characterise the neurodegenerative states of AD pathology are not prevalent, especially in a semiparametric context. In this study, we extended parametric HMMs to accommodate the functional effects of hippocampus and age on cognitive decline across four neurodegenerative states, namely, CN, EMCI, LMCI, and AD. The functional effect of hippocampus on cognitive function exhibited a descending trend as hippocampus grows regardless of states. This descending trend became more pronounced for EMCI and LMCI states than for CN and AD states, implying that atrophy in hippocampal volume had increasingly impaired patients’ cognitive ability, especially during the progression from EMCI to LMCI. On the contrary, age affected cognitive function mainly in LMCI and AD states. Elderly LMCI or AD patients suffered from more increasing neurodegeneration than relatively young patients.

Our model incorporates correlated random effects to account for individual and/or contextual differences in the progression of cognitive decline and in between-state transition. Large inter-individual variability is a prominent feature of the ADNI dataset and many other longitudinal datasets. As we demonstrated in the ADNI study, accounting for such differences can dramatically improve model fit, as evidenced by an apparent improvement in DIC value between models with and without random effects. In addition, the correlation between the random effects enhances the model capability of accommodating the situation where some omitted covariates influence both the state-dependent observation process and the hidden-state transition process. Another appealing feature of this study is that it implements a full Bayesian analysis along with efficient MCMC methods. The sampling-based Bayesian approach is not only applicable to the current parameter-rich BMSHM2 but also possesses potential to address highly complex problems with which huge challenges are confronted by ML-based procedures.

The present study can be extended in several directions: First, we considered the nonparametric modeling only in the conditional model. Generalizing the parametric transition model to a semiparametric or nonparametric one can further enhance model flexibility and analytic power. However, the statistical analysis of such comprehensive models can be challenging because the computational burden and sample size often limit the complexity of candidate models. Thus, the feasibility of this extension requires further investigation. Second, in the application to the ADNI dataset, a highly comprehensive characterization of cognitive function is to group the FAQ, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, and Mini-Mental State Examination into an integrated latent construct through multivariate techniques such as factor analysis (e.g. Song et al., 2016). Finally, this study did not consider missing data. Given that missingness is very common in longitudinal settings, accommodation of missing responses and/or missing covariates in the context of BMSHM2s is both of scientific interest and of practical value. These advances certainly require substantial efforts for further investigation.

Appendix

Full Conditional Distributions

(I) Full conditional distributions of Zit

We follow Baum et al. (1970) to adopt a recursive method to sample Zit from the full conditional distribution efficiently as follows:

Let yi = {yi1, …, yiT } and Di = {di1, …, diT}, then we have

| (A1) |

| (A2) |

| (A3) |

We first initialize qi1(yi, Di, wi, Zit|θ) = p(yi1, di1, wi, Zit|θ) = p(yi1, di1|Zi1, θ)p(Zi1|θ) and calculate qit(yi, Di, wi, Zit|θ) for t = 2, …, T, in a recursion manner as follows:

| (A4) |

where p(Zit|Zi,t−1 = u, wi2, θ), p(yit, dit|Zit, wi1, θ) and p(wi|θ) can be calculated through Equation (11).

Similarly, we initialize q̄iT (yi, Di|wi, ZiT, θ) = 1 and calculate q̄it(yi, Di|wi, Zit, θ) for t = T − 1, …, 1 as follows:

| (A5) |

| (A6) |

Thus, Zit can be directly generated from (A1) when all qit(·)s and q̄it(·)s defined in (A4) and (A5) are well calculated.

(II) Full conditional distributions of wi

| (A7) |

where pitu0 and pitus can be calculated via Equation (12).

(III) Full conditional distributions of μs, γs, ψs, and Φ

| (A8) |

where R* = (R0 + WWT)−1, and

(IV) Full conditional distributions of βsj and θsj

| (A9) |

where , and is an ns × 1 vector with

According to Panagiotelis and Smith (2008), sampling an observation βsj from truncated normal (A9) is equivalent to sampling an observation from and then transforming to βsj by

| (A10) |

where . Moreover,

| (A11) |

(V) Full conditional distributions of τs, ζus, and α

| (A12) |

where pitu0 and pitus can be calculated via Equation (12).

Contributor Information

Kai Kang, Department of Statistics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Jingheng Cai, Department of Statistics, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China.

Xinyuan Song, Department of Statistics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Hongtu Zhu, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas, Houston, USA.

References

- Albert PS, McFarland HF, Smith ME, Frank JA. Time series for modelling counts from a relapsingremitting disease: Application to modelling disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Statistics in Medicine. 1994;13:453–466. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780130509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimers disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimers Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman RM, Petkau AJ. Application of hidden Markov models to multiple sclerosis lesion count data. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;24:2335–2344. doi: 10.1002/sim.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman RM. Mixed hidden Markov models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2007;102:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A, Jedidi K. Bayesian factor analysis for multilevel binary observations. Psychometrika. 2000;65:475–498. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci F, Farcomeni A. A multivariate extension of the dynamic logit model for longitudinal data based on a latent Markov heterogeneity structure. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2009;104:816–831. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci F, Farcomeni A, Pennoni F. Latent Markov Models for Longitudinal Data. Florida: Chapman & Hall/CRC, Taylor and Francis Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baum LE, Petrie T, Soules G, Weiss N. A maximization technique occurring in the statistical analysis of probabilistic functions of Markov chains. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1970;41:164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Behseta S, Kass RE, Wallstrom GL. Hierarchical models for assessing variability among functions. Biometrika. 2005;92:419–434. [Google Scholar]

- Berry SM, Carroll RJ, Ruppert D. Bayesian smoothing and regression splines for measurement error problems. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2002;97:160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Biller C, Fahrmeir L. Bayesian varying-coefficient models using adaptive regression splines. Statistical Modelling. 2001;1:195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cappé O, Moulines E, Rydén T. Inference in Hidden Markov Models. Springer; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Celeux G, Forbes F, Robert CP, Titterington DM. Deviance information criteria for missing data models. Bayesian Analysis. 2006;1:651–674. [Google Scholar]

- Chi YY, Ibrahim JG. Regime-switching bivariate dual change score model. Biometrics. 2006;62:432–445. [Google Scholar]

- Chow SM, Grimm KJ, Filteau G, Dolan CV, McArdle JJ. Regimes-witching bivariate dual change score model. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2013;48(4):463–502. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2013.787870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boor C. A Practical Guide to Splines. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2001. revised edition. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Wolk D. Biomarker-based prediction of progression in MCI: comparison of AD-signature and hippocampal volume with spinal fluid amyloid-β and tau. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2013;5:55. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo I, Genovese CR, Kass RE. Bayesian curve fitting with free-knot splines. Biometrika. 2001;88:1055–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Dunson DB. Bayesian latent variable models for clustered mixed outcomes. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B. 2000;62:355–366. [Google Scholar]

- Dunson DB. Dynamic latent trait models for multidimensional longitudinal data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2003;98:555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Eilers PHC, Marx BD. Flexible smoothing with B-splines and penalties. Statistical Science. 1996;11:89–121. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrmeir L, Raach A. A Bayesian semiparametric latent variable model for mixed responses. Psychometrika. 2007;72:327–346. [Google Scholar]

- Frühwirth-Schnatter S. Markov chain Monte Carlo estimation of classical and dynamic switching and mixture models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:194–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S. The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings WK. Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika. 1970;57:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ip E, Zhang Q, Rejeski J, Harris T, Kritchevsky S. Partially ordered mixed hidden Markov model for the disablement process of older adults. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2013;108:370–384. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2013.770307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Petersen RC, O’brien PC, Tangalos EG. MR-based hippocampal volumetry in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42:183–183. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Senjem MS, Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Jagust WJ, Weiner MW, Jack CR Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Focal hemosiderin deposits and -amyloid load in the ADNI cohort. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013;9:S116–S123. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Kesslak JP, Nalcioglu O, Cotman CW. Quantification of magnetic resonance scans for hippocampal and parahippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:51–51. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang S, Brezger A. Bayesian P-splines. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2004;13:183–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Zhu H, Kong D, Wang Y, Giovanello KS, Ibrahim JG. BFLCRM: A Bayesian functional linear Cox regression model for predicting time to conversion to Alzheimer’s disease. The Annals of Applied Statistics. 2015;9:2153–2178. doi: 10.1214/15-AOAS879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Song XY. Evaluation of the Bayesian and maximum likelihood approaches in analyzing structural equation models with small sample sizes. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:653–686. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3904_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay J, Laurin D, Verreault R, Hbert R, Helliwell B, Hill GB, McDowell I. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;156:445–453. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruotti A. Mixed hidden Markov models for longitudinal data: an overview. International Statistical Review. 2011;79:427–454. [Google Scholar]

- Metropolis N, Rosenbluth AW, Rosenbluth MN, Teller AH, Teller E. Equations of state calculations by fast computing machine. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1953;21:1087–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Myers SC, Majluf NS. Corporate financing and investment decision when firms have information that investor do not have. Journal of Financial Economic. 1984;13:187–221. [Google Scholar]

- Okuizumi K, Onodera O, Tanaka H, Kobayashi H, Tsuji S, Takahashi H, Tsuji S, Takahashi H, Oyanagi K, Seki K, Tanaka M, Naruse S, Miyatake T, Mizusawa H, Kanazawa I. ApoE-ε4 and earlyonset Alzheimer’s. Nature genetics. Journal of Financial Economic. 1994;7:10–11. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-10b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotelis A, Smith M. Bayesian identification, selection and estimation of semiparametric functions in high-dimensional additive models. Journal of Econometrics. 2008;143:291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. Journal of internal medicine. 2004;256(3):183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, Bennett D, Doody R, Ferris S, Galasko D, Jin S, Kaye J, Levey A, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, Dyck CH, Thal LJ. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:2379–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson S, Green PJ. On Bayesian analysis of mixtures with an unknown number of components (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1997;59:731–792. [Google Scholar]

- Schmittmann VD, Dolan CV, van der Maas HL, Neale MC. Discrete latent Markov models for normally distributed response data. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:461–488. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4004_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SL, James GM, Sugar CA. Hidden Markov models for longitudinal comparisons. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2005;100:359–369. [Google Scholar]

- Song XY, Lu ZH. Semiparametric latent variable models with Bayesian P-splines. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2010;19:590–608. [Google Scholar]

- Song XY, Xia YM, Zhu HT. Hidden Markov latent variable models with multivariate longitudinal data. Biometrics. 2016;73:313–323. doi: 10.1111/biom.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2002;64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter DJ, Thomas A, Best NG, abd Lunn D. WinBUGS User Manual. Version 1.4. MRC Biostatistics Unit; Cambridge, England: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner MA, Wong WH. The calculation of posterior distributions by data augmentation (with discussion) Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1987;82:528–550. [Google Scholar]

- Wulfsohn MS, Tsiatis AA. A joint model for survival and longitudinal data measured with error. Biometrics. 1997;53:330–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Langeheine R, Böckenholt U. Latent Markov models with time-constant and time-varying covariates. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1999;24:178–205. [Google Scholar]