Abstract

Hispanics/Latinos are burdened by chronic kidney disease (CKD). The role of acculturation in this population has not been explored. We studied the association of acculturation with CKD and cardiovascular risk factor control. We performed cross-sectional analyses of 13,164 U.S. Hispanics/Latinos enrolled in the HCHS/SOL Study between 2008 and 2011. Acculturation was measured using the language and ethnic social relations subscales of the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics, and proxies of acculturation (language preference, place of birth and duration of residence in U.S.). CKD was defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g. On multivariable analyses stratified by age, lower language subscale score was associated with higher odds of CKD among those older than 65 (OR 1.29, 95% CI, 1.03, 1.63). No significant association was found between proxies of acculturation and CKD in this age strata. Among individuals aged 18–44, a lower language subscale score was associated with lower eGFR (β = −0.77 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI −1.43, −0.10 per 1 SD increase) and a similar pattern was observed for ethnic social relations. Among those older than 65, lower language subscale score was associated with higher log-albuminuria (β = 0.12, 95% CI 0.03, 0.22). Among individuals with CKD, acculturation measures were not associated with control of cardiovascular risk factors. In conclusion, lower language acculturation was associated with a higher prevalence of CKD in individuals older than 65. These findings suggest that older individuals with lower language acculturation represent a high risk group for CKD.

Keywords: Acculturation, Hispanics, Latinos, Chronic kidney disease, Cardiovascular risk factors

Highlights

-

•

Among Hispanics/Latinos, lower language acculturation was associated with a higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease in older individuals.

-

•

Based on our findings, older individuals with lower language acculturation represent a high-risk group for chronic kidney disease.

1. Introduction

Hispanic/Latino individuals residing in the U.S. experience a higher incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) than non-Hispanics (United States Renal Data System, 2015). Furthermore, the number of U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults with prevalent ESRD has grown by >60% in the last decade (United States Renal Data System, 2015). It is well known that Hispanic/Latino individuals face many barriers to health care (Thamer et al., 1997; Harris, 2001). Those with lower acculturation may face even greater barriers that likely contribute to progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and may explain the high incidence of ESRD in this population (Lora et al., 2011). However, the association of level of acculturation with CKD has not been well characterized.

Acculturation is the process by which individuals adopt the attitudes, values, customs, beliefs, and behaviors of another culture (LaFromboise et al., 1993). Individuals adopt these cultural attributes to varying degrees. An individual's level of acculturation influences their health practices and beliefs (Ayala et al., 2008; Constantine et al., 2009; Hubbell et al., 1996; Jacobs et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2009; Solis et al., 1990), which can lead to differences in health outcomes. For example, higher acculturation has been associated with increased rates of cardiovascular risk factors (Kandula et al., 2008; Moran et al., 2007). However, the influence of acculturation has not been well studied in the context of CKD (Lora et al., 2011). Understanding the influence of acculturation may help to identify individuals who are at risk for the development or progression of CKD. The purpose of this study was to examine the cross-sectional association of acculturation, assessed using an acculturation scale and proxy measures, with prevalent CKD and measures of kidney function in a large and diverse cohort of Hispanics/Latinos residing in the U.S. In addition, given the known association of CKD with cardiovascular risk (Lora et al., 2011), we investigated the association of acculturation with control of cardiovascular risk factors among individuals with CKD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

We performed cross-sectional analyses of baseline examination data on non-institutionalized Hispanics/Latinos enrolled in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). The design and methods of the HCHS/SOL have been previously published (Sorlie et al., 2010; Lavange et al., 2010). Briefly, the HCHS/SOL is a community-based, longitudinal cohort study of 16,415 Hispanic/Latino adults aged 18–74 at baseline examination (2008–2011). The goals of the study are to describe the prevalence of risk and protective factors for chronic conditions and to quantify mortality and disease over time in Hispanic/Latinos living in the U.S. Participants were enrolled through a stratified two-stage area probability sampling of census block groups and households in four U.S. field centers (Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; Bronx, NY; San Diego, CA). This strategy of enrollment included oversampling from certain strata to ensure diversity of Hispanic/Latino background and socioeconomic status. The study protocol was approved by each center's Institutional Review Board, and the research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Study participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Instruments and measurements

Data was obtained from the baseline in-person visit of the HCHS/SOL Study. During this visit participants completed questionnaires, anthropometric measurements (height, weight) were obtained, and fasting venous blood and urine samples were collected. Hispanic/Latino background group was self-reported; individuals who reported more than one background group were categorized as “other” and were excluded from the analysis. Socioeconomic status factors including income, educational attainment, and insurance status were self-reported. Participants were asked to bring their medications to the visit in order to ascertain medication use. Participants also completed a medical history questionnaire. Cardiovascular disease and tobacco use were self-reported. Hypertension was defined as self-reported history of hypertension, a systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥140 mmHg, diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medications. Diabetes was defined as self-reported history of diabetes, fasting plasma glucose of ≥126 mg/dl, 2-hour post-load glucose level of ≥200 mg/dl, a glycosylated hemoglobin ≥6.5%, or use of anti-diabetes medication. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in Kg by height in m2. Three separate seated BP readings were obtained after a 5 min rest using an automatic sphygmomanometer (OMRON HEM-907 XL). BP was defined as the average of the second and third BP measurements.

Acculturation was measured using the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) which has two subscales, language and ethnic social relations. The original SASH was developed and validated in diverse Hispanic groups and has strong reliability (coefficient alpha = 0.92) (Marin et al., 1987). The language subscale includes five questions regarding what language (English vs. Spanish) participants read, speak, and think in (Supplement). The ethnic social relations subscale has 4 items that measure preference for the ethnicity of social contacts. Scores for each item range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher levels of acculturation. Responses provided are averaged within scales. Three proxies of acculturation were assessed: language preference, place of birth, and duration of residence in the U.S. mainland. Participants were offered surveys in either Spanish or English, and language preference was determined by the language chosen. Place of birth was self-reported, and participants were categorized as either U.S.-born, if born in the 50 U.S. states or Washington D.C. area; or foreign-born, if born outside the U.S., including Puerto Rico. Foreign-born individuals were asked to report their duration of residence in the mainland U.S. Based on prior studies; participants were categorized as having lived in the US <10 years or ≥10 years (Salinas et al., 2014).

Creatinine was measured in serum and urine on a Roche Modular P Chemistry Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics Corporation) using a creatinase enzymatic method (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN 46250). Serum creatinine measurements were isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS) traceable. Albumin was measured in urine using an immunoturbidometric method on the ProSpec nephelometric analyzer (Dade Behring GMBH. Marburg, Germany D-35041). Serum Cystatin C was measured using a turbidimetric method on the Roche Modular P Chemistry Analyzer (Gentian AS, Moss, Norway). The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-Epi) creatinine-cystatin C equation (Inker et al., 2012). CKD was defined as an estimated GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥30 mg/g. Control of hypertension was defined as systolic BP <140 and diastolic BP <90 mmHg (Chobanian et al., 2003), and control of diabetes was defined as the American Diabetes Association goal for glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) <7% (http://www.ndei.org/ADA-diabetes-management-guidelines-glycemic-targets-A1C-PG.aspx.html, n.d.). Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blocker use was also assessed among individuals with CKD.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using complex survey methods with SAS software, version 9.2. All reported values were weighted to adjust for sampling probability and non-response according to guidelines established by the HCHS/SOL Steering and Data Analysis Committees. Using ANOVA, mean language scale score and mean ethnic social relations scale scores were compared by Hispanic/Latino background group, age, sex, education income, health insurance status, tobacco use, BMI, and comorbidities. Descriptive statistics for demographics and clinical variables were summarized as mean (standard error) for continuous variables, and as weighted percentages for categorical variables. We used ANOVA or Chi-square to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively, by proxy of acculturation category. Multivariable linear and logistic regression were performed using a priori chosen models to examine the association of language subscale score and ethnic social relations subscale score with prevalent CKD, albuminuria and eGFR in the overall cohort, and with control of cardiovascular risk factors among individuals with CKD. Odds ratios were calculated per 1 SD deviation decrease in subscale score. Based on existing literature, potential confounding variables included age, sex, education, income, insurance status, Hispanic/Latino background, hypertension, diabetes, eGFR, and albuminuria (Lora et al., 2011; Lora et al., 2009; Norris and Nissenson, 2008; Hemmelgarn et al., 2010; Fischer et al., 2016). We evaluated age, sex, and education as effect modifiers of the association between acculturation and kidney function. Since the distribution of U.S. Hispanic/Latino individuals tends to concentrate based on background in specific geographic areas, we adjusted for field center, Hispanic/Latino background, and an interaction term between the two variables. All hypothesis tests were 2-sided, with a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. HCHS/SOL target population characteristics

A total of 13,164 participants were included in the analysis. Compared to those included in the analyses, individuals who were excluded due to missing data (n = 3251) had similar language and ethnic social relations subscale scores (1.99 vs. 2.08, and 2.23 vs. 2.22) and similar prevalence of English language preference (24% vs. 29%), non U.S.-born (78% vs. 73%) and foreign born living in the U.S. <10 years (34% vs 44%).

Approximately 40% of participants were between the ages of 18 to 44, 52% were aged 45 to 64; and 8% were 65 years or older. More than half of participants (59%) were women. The Hispanic/Latino background distribution was as follows: 42% Mexican, 14% Cuban, 17% Puerto Rican, 9% Dominican, 11% Central American, and 7% South American.

3.2. HCHS/SOL target population characteristics by acculturation subscale score

For the language acculturation subscale, lower scores were observed in older age categories as compared to younger age categories and in women as compared to men (Table 1). Individuals with Cuban background had the lowest subscales scores, whereas those with Puerto Rican background had the highest subscales scores. Lower subscale scores were observed with lower educational attainment, lower income, lack of insurance, non-smoking status, presence of diabetes, hypertension, and self-reported cardiovascular disease, and BMI <30 kg/m2. Compared to individuals without CKD, individuals with CKD had lower language acculturation subscales scores. Furthermore, language subscales scores were lower in individuals with eGFR <90 ml/min/1.73 m2 compared to those with eGFR ≥90 ml/min/1.73 m2 and in individuals with albuminuria (UACR ≥30 mg/g) as compared to those without albuminuria. Similar patterns were observed for the social relations subscale.

Table 1.

HCHS/SOL Target population characteristics by acculturation subscales and proxies of acculturation at baseline visits completed between 2008 and 2011.

| Variable | SASH subscale, Mean (se) |

Proxies of acculturation, % |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language preference |

Place of birth |

Duration of residence |

||||||

| Language | Social relations | English | Spanish | US-born | Non US-born | ≥10 yrs. in US | <10 yrs. in US | |

| Number of participants | 13,164 | 13,164 | 2521 | 10,643 | 2174 | 10,990 | 8078 | 2912 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–44 | 2.2 (0.03)a | 2.3 (0.01)a | 74.5 | 54.4† | 82.0 | 52.9† | 43.8 | 70.8† |

| 45–64 | 1.8 (0.03)⁎ | 2.2 (0.02)⁎ | 22.6 | 35.8† | 16.9 | 37.0† | 43.9 | 23.5† |

| >65 | 1.5 (0.04)⁎ | 2.1 (0.03)⁎ | 2.9 | 9.8† | 1.1 | 10.1† | 12.3 | 5.7† |

| Sex, Male | 2.1 (0.03)a | 2.3 (0.02)a | 51.0 | 48.3 | 52.0 | 48.1† | 47.7 | 48.9† |

| Female | 1.9 (0.03)⁎ | 2.2 (0.01)⁎ | 49.0 | 51.7 | 48.0 | 51.9† | 52.3 | 51.1† |

| Background | ||||||||

| Mexican | 2.0 (0.03)a | 2.2 (0.01)a | 38.7 | 41.9 | 46.3 | 39.7† | 41.3 | 36.5† |

| Cuban | 1.5 (0.03)⁎ | 2.0 (0.02)⁎ | 6.1 | 24.1† | 6.6 | 23.5† | 18.4 | 33.4† |

| Puerto Rican | 3.0 (0.05)⁎ | 2.5 (0.02)⁎ | 40.0 | 9.2† | 37.0 | 10.9† | 14.4 | 4.0† |

| Dominican | 1.9 (0.06)⁎ | 2.3 (0.02)⁎ | 9.1 | 10.2 | 6.5 | 10.9† | 12.0 | 8.6† |

| Central American | 1.6 (0.04)⁎ | 2.1 (0.03)⁎ | 3.8 | 8.6† | 2.3 | 8.9† | 8.5 | 9.7† |

| South American | 1.6 (0.04)⁎ | 2.3 (0.03)⁎ | 2.3 | 6.0† | 1.3 | 6.2† | 5.4 | 7.8† |

| Education | ||||||||

| <high school diploma | 1.7 (0.03)a | 2.1 (0.02)a | 19.8 | 34.9† | 20.6 | 34.3† | 38.9 | 25.2† |

| ≥high school | 2.1 (0.03)⁎ | 2.3 (0.01)⁎ | 80.2 | 65.1† | 79.5 | 65.7† | 61.1 | 74.8† |

| Income | ||||||||

| ≤ $20,000 | 1.8 (0.03)a | 2.2 (0.01)a | 35.3 | 50.2† | 33.7 | 50.2† | 47.7 | 55.1† |

| >$20,000 | 2.2 (0.03)⁎ | 2.3 (0.01)⁎ | 64.7 | 49.8† | 66.3 | 49.8† | 52.3 | 44.9† |

| Insured | 2.3 (0.03)a | 2.3 (0.01)a | 68.0 | 44.8† | 65.3 | 46.2† | 53.6 | 31.8† |

| Uninsured | 1.7 (0.03)⁎ | 2.2 (0.01)⁎ | 32.0 | 55.2† | 34.7 | 53.8† | 46.4 | 68.2† |

| Current smoker | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.2 (0.05)a | 2.3 (0.02)a | 28.4 | 18.7† | 28.2 | 19.0† | 19.2 | 18.8† |

| No | 1.9 (0.02)⁎ | 2.2 (0.01)⁎ | 71.6 | 81.3† | 71.8 | 81.0† | 80.8 | 81.2† |

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.7 (0.03)a | 2.2 (0.02)a | 9.9 | 15.8† | 7.9 | 16.2† | 19.9 | 9.0† |

| No | 2.0 (0.03)⁎ | 2.3 (0.01)⁎ | 90.1 | 84.2† | 92.1 | 83.8† | 80.2 | 91.0† |

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.8 (0.03)a | 2.2 (0.02)a | 15.8 | 24.1† | 12.6 | 24.7† | 28.7 | 16.9† |

| No | 2.1 (0.03)⁎ | 2.3(0.01)⁎ | 84.2 | 76.0† | 87.5 | 75.3† | 71.3 | 83.1† |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.9 (0.06)a | 2.19 (0.03)a | 5.5 | 6.1 | 4.1 | 6.5† | 7.9 | 3.9† |

| No | 2.0 (0.03)⁎ | 2.23 (0.01)⁎ | 94.5 | 93.9 | 96.0 | 93.5† | 92.1 | 96.2† |

| Body mass index | ||||||||

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 2.1 (0.04)a | 2.24 (0.02)a | 45.6 | 38.8† | 44.4 | 39.3† | 43.0 | 31.9† |

| <30 kg/m2 | 2.0 (0.03)⁎ | 2.23 (0.01)⁎ | 54.4 | 61.3† | 55.7 | 60.7† | 57.0 | 68.1† |

| CKD | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.9 (0.04)a | 2.19 (0.02)a | 9.4 | 11.2† | 8.8 | 11.4† | 13.0 | 8.2† |

| No | 2.0 (0.03)⁎ | 2.24 (0.01)⁎ | 90.6 | 88.8† | 91.2 | 88.7† | 87.0 | 91.8† |

| eGFR | ||||||||

| ≥90 ml/min/1.73m2 | 2.0 (0.03)a | 2.3 (0.01)a | 84.3 | 80.4† | 87.0 | 79.8† | 76.4 | 86.5† |

| 60–89 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 1.9 (0.04)⁎ | 2.2 (0.02)⁎ | 13.8 | 17.1† | 11.7 | 17.6† | 20.5 | 12.0† |

| <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 1.8 (0.07)⁎ | 2.2 (0.05)⁎ | 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 2.6† | 3.2 | 1.5† |

| UACR ≥30 mg/g | 1.9 (0.05)⁎ | 2.19 (0.02)a | 8.4 | 9.8 | 8.1 | 9.8 | 11.1 | 7.3 |

| UACR <30 mg/g | 2.0 (0.03)⁎ | 2.24 (0.01)⁎ | 91.6 | 90.2 | 91.9 | 90.2 | 88.9 | 92.7 |

eGFR: † p < 0.05 for comparisons across categories of proxies of acculturation; estimated glomerular filtration rate; UACR: Urine albumin to creatinine ratio.

Referent group.

p < 0.05 for comparisons across categories of proxies of acculturation.

3.3. HCHS/SOL target population participant characteristics by proxies of acculturation

Table 1 provides characteristics by proxies of acculturation including language preference, place of birth, and duration of residence in the U.S. Compared to individuals who preferred to communicate in English, those with a Spanish language preference were older, had lower educational attainment, lower income, and were less likely to have health insurance. Cubans and Central and South Americans were more likely to have a Spanish language preference and Puerto Ricans were more likely to have an English language preference. Additionally, individuals who preferred Spanish were less likely to smoke and had a higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. The prevalence of CKD was higher in individuals who preferred Spanish compared to English. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of albuminuria by language preference. Compared to U.S.-born individuals, foreign-born individuals were older, more likely to be female, had lower educational attainment, lower income, and were less likely to have insurance or be a current smoker. Puerto Ricans and Mexicans were more likely to be U.S.-born. In addition, foreign-born individuals had a higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, but a lower prevalence of BMI ≥30 kg/m2. The prevalence of CKD was higher in foreign-born individuals compared to U.S.-born individuals. Furthermore, foreign-born participants had a higher prevalence of eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. There was no significant difference in albuminuria between the two groups.

Among foreign-born individuals, individuals who had lived in the U.S. <10 years were younger and more likely to be male compared to those who had lived in the U.S. ≥10 years. Additionally, those living in the U.S. <10 years (vs. ≥10 years) had higher educational attainment but were more likely to have income <$20,000 and lack health insurance. Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Dominicans were more likely to have lived in the U.S. ≥10 years. Individuals who had lived in the U.S. <10 years were also less likely to be current smokers and had a lower prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. In addition, individuals who had lived in the U.S. ≥10 years had a higher prevalence of CKD. The prevalence of albuminuria was similar in both groups.

3.4. Association of acculturation with chronic kidney disease

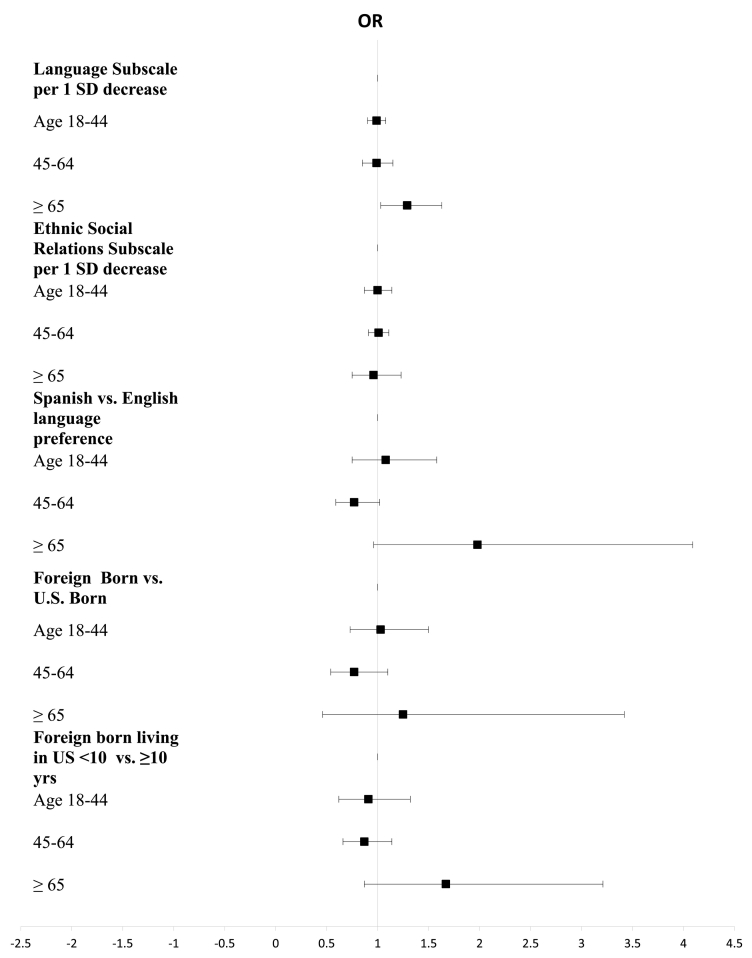

We found age to be a significant effect modifier of the association between acculturation measures and CKD but there was no significant effect modification by sex and education. On stratified analyses by age, lower language acculturation subscale score was associated with a higher odds of CKD among those older than 65 (OR 1.29, 95% CI, 1.03, 1.63, Fig. 1). Spanish language preference was also associated with higher odds of CKD, but this association did not reach statistical significance. We did not find a significant association in the other age strata and did not observe an association between other measures of acculturation and CKD.

Fig. 1.

Association of Acculturation with Prevalent CKD.*

*Adjusted for gender, education, income, insurance status, background, site, hypertension, and diabetes.

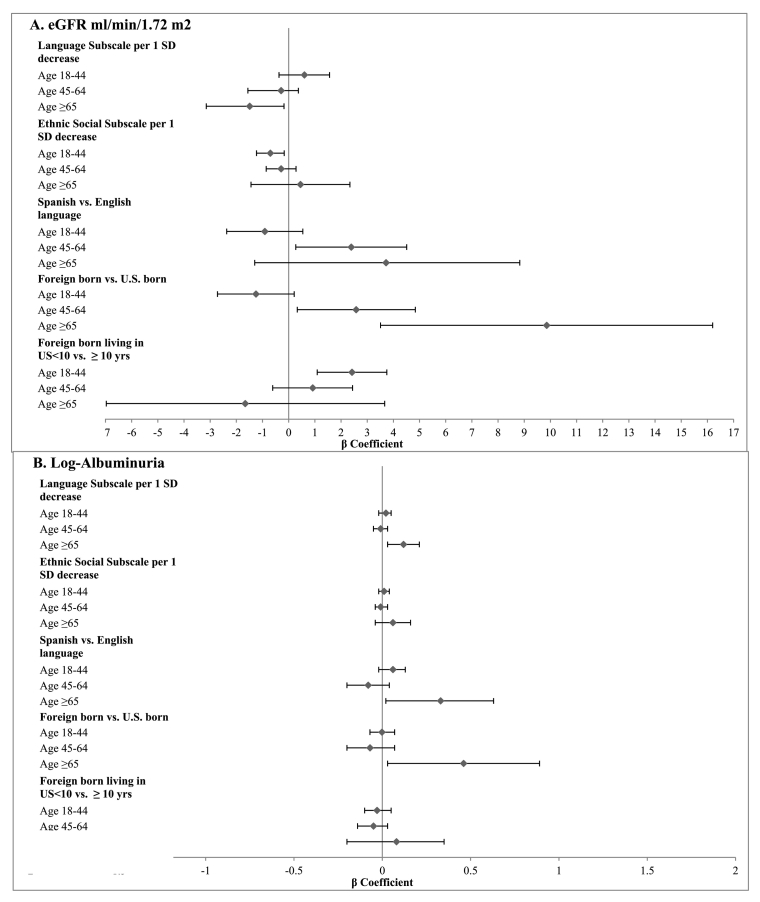

We also examined the association between acculturation and measures of kidney function. Among individuals aged 18–44, lower language subscale scores were associated with lower eGFR (β = −0.77 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI −1.42, −0.10 per 1 SD decrease) (Fig. 2A). Among older individuals, a lower score was associated with higher eGFR, but this association was not statistically significant. A similar pattern was observed for the ethnic social relations subscale score. Among individuals 45 to 65 years, Spanish language preference was associated with a higher eGFR (β = 2.39 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI 0.27, 4.51 per 1 SD decrease) but this association was not observed in the other two age strata. Among individuals older than 44 years, being foreign-born was associated with a higher eGFR than being U.S.-born (β = 2.58 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI 0.33, 4.84 and β = 9.86 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI 3.51, 16.20 for age 45–64 and age ≥65, respectively). Among foreign-born individuals, length of residency in the U.S. <10 years was associated with higher eGFR among individuals 18 to 44 (β = 2.42 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI 1.09, 3.75) but this association was not significant in the other two age strata. For the outcome albuminuria, among those older than 65, lower language subscale score was associated with more albuminuria (β = 0.12 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI 0.03, 0.22) (Fig. 2B). There was no significant association between the other measures of acculturation and albuminuria.

Fig. 2.

Association of Acculturation with Kidney Function.*

*Adjusted for age, gender, education, income, insurance status, background, site, background*site. In addition, eGFR models are adjusted for log-albuminuria and albuminuria models are adjusted for eGFR. eGFR-estimated glomerular filtration rate.

In multivariable analyses, we did not find a significant association between measures of acculturation and control of cardiovascular risk factors among individuals with CKD.

4. Discussion

This study represents the first comprehensive evaluation of the association of acculturation with CKD in a large and diverse U.S. Hispanic/Latino cohort. Overall, we found that a lower language subscale score was associated with a higher prevalence of CKD in individuals older than 65. These findings suggest that older individuals with low language acculturation may represent a high risk group for CKD.

In this study, the significant association between lower language acculturation and prevalent CKD in older individuals may have been due to poor long-term control of CKD risk factors. Lower language acculturation may influence health through various mechanisms. Individuals with lower acculturation likely have limited English language proficiency which may lead to challenges in accessing an English language-based health system (Lora et al., 2011; Timmins, 2002). In the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Spanish language, was associated with lower utilization of preventive health services in Mexican Americans (Solis et al., 1990). Furthermore, once care is accessed, individuals with limited English language proficiency may have difficulty communicating with health care providers, in particular if the provider does not speak Spanish or have access to adequate translation services. Ineffective communication may lead to poor understanding of instructions and decreased adherence with therapies (Lora et al., 2009). Additionally, individuals with lower language acculturation have a higher prevalence of limited health literacy which has been associated with decreased understanding of disease, lower adherence, and poor self-management of chronic disease (Williams et al., 1995; Williams et al., 1998; Kalichman et al., 2008).

Socioeconomic status may be another important factor influencing the association between lower language subscale scores and a higher prevalence of CKD in older individuals. We found that individuals with lower socioeconomic status had lower language subscale scores than those with higher socioeconomic status. It is well established that individuals with lower socioeconomic status are at increased risk for CKD (Bruce et al., 2010; Klag et al., 1997). Multiple factors are likely to be responsible for this association including reduced access to care, inability to afford therapies, and suboptimal control of diabetes and hypertension (Norris and Nissenson, 2008).

Consistent with our findings, Spanish language preference was associated with a higher odds of CKD, but this association did not reach statistical significance. This may be because the language subscale includes questions regarding in what language participants most often read, think, and speak at home and with friends. Therefore, it provides a more comprehensive assessment of language acculturation than self-reported language preference. Future work is needed to evaluate the implementation of language acculturation assessment in the clinical setting.

The size of the older U.S. Hispanic/Latino population is growing and is projected to exceed 8 million by 2030 (Ortman et al., n.d.). Therefore our finding regarding the association between lower language acculturation and higher prevalence of CKD in older individuals is of particular significance. From the clinician's perspective, our findings support the practice of CKD screening in older Hispanic/Latino individuals with low language acculturation. From the healthcare system perspective, unique needs of this population include Spanish-speaking providers, availability of translation services, and culturally tailored educational materials.

We also found that the association between proxies of acculturation and kidney function varied by age group. However, the observed beta coefficients were small and of questionable clinical importance. Nonetheless, these findings highlight the complexity of the association of acculturation with health outcomes. Higher acculturation in Hispanics/Latinos has been associated with unhealthy behaviors such as increased tobacco use and increase consumption of fast food (Liu et al., 2009; Pérez-Escamilla and Putnik, 2007; Pérez-Escamilla, 2009). However, higher acculturation has also been associated with improved access to care and use of preventive services (Lara et al., 2005). Furthermore, similar to our findings, an analysis of data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis found that the association between language and kidney function varied by age and that Spanish speakers younger than age 65 had a slightly higher mean eGFR (Day et al., 2011). Long-term follow-up of the HCHS/SOL cohort is needed to assess the association of acculturation with incident CKD.

The strengths of our study include the large, multi-center cohort with adequate representation of varied Hispanic/Latino backgrounds. Additionally, we used subscales from a validated acculturation scale (Marin et al., 1987) and three different proxies of acculturation. However, our study has several limitations. The diagnosis of CKD was based on a single measurement of serum creatinine, cystatin C, and urine albumin. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow for inferences regarding causality. Lastly, health literacy was not assessed.

In conclusion, lower language acculturation was associated with a higher prevalence of CKD in individuals older than 65. Health care providers should be aware that older Hispanic/Latino individuals with low language acculturation may represent a particularly vulnerable segment of the population at risk for CKD. Future research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying this association and guide the development of effective strategies to address barriers related to acculturation.

Funding

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos was carried out as a collaborative study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01-HC65233), University of Miami (N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (N01-HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01-HC65237). The following Institutes/Centers/Offices contribute to the HCHS/SOL through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIH Institution-Office of Dietary Supplements. C.M.L. is funded by funded by the NIDDK K23 DK091313, A.C.R. is funded by NIDDK K23 DK094829, and J.P.L. is funded by the NIDDK K24 DK092290.

Disclosures

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL for their important contributions. Investigators website - http://www.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.04.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ayala G.X., Baquero B., Klinger S. A systematic review of the relationship between acculturation and diet among Latinos in the United States: implications for future research. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008;108(8):1330–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M.A., Beech B.M., Crook E.D. Association of socioeconomic status and CKD among African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010;55(6):1001–1008. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chobanian A.V., Bakris G.L., Black H.R. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantine M.L., Rockwood T.H., Schillo B.A., Castellanos J.W., Foldes S.S., Saul J.E. The relationship between acculturation and knowledge of health harms and benefits associated with smoking in the Latino population of Minnesota. Addict. Behav. 2009;34(11):980–983. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day E.C., Li Y., Diez-Roux A. Associations of acculturation and kidney dysfunction among Hispanics and Chinese from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011;26(6):1909–1916. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M.J., Hsu J.Y., Lora C.M. CKD progression and mortality among Hispanics and non-Hispanics. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M.I. Racial and ethnic differences in health care access and health outcomes for adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):454–459. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmelgarn B.R., Manns B.J., Lloyd A. Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303(5):423–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADA diabetes guidelines glycemic targets A1C|NDEI. http://www.ndei.org/ADA-diabetes-management-guidelines-glycemic-targets-A1C-PG.aspx.html (Accessed October 25, 2016)

- Hubbell F.A., Chavez L.R., Mishra S.I., Valdez R.B. Beliefs about sexual behavior and other predictors of Papanicolaou smear screening among Latinas and Anglo women. Arch. Intern. Med. 1996;156(20):2353–2358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inker L.A., Schmid C.H., Tighiouart H. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367(1):20–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs E.A., Karavolos K., Rathouz P.J., Ferris T.G., Powell L.H. Limited English proficiency and breast and cervical cancer screening in a multiethnic population. Am. J. Public Health. 2005;95(8):1410–1416. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S.C., Pope H., White D. Association between health literacy and HIV treatment adherence: further evidence from objectively measured medication adherence. J. Int. Assoc. Phys. AIDS Care. 2008;7(6):317–323. doi: 10.1177/1545109708328130. (Chic Ill 2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandula N.R., Diez-Roux A.V., Chan C. Association of acculturation levels and prevalence of diabetes in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1621–1628. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klag M.J., Whelton P.K., Randall B.L., Neaton J.D., Brancati F.L., Stamler J. End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men. 16-year MRFIT findings. JAMA. 1997;277(16):1293–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T., Coleman H.L., Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: evidence and theory. Psychol. Bull. 1993;114(3):395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M., Gamboa C., Kahramanian M.I., Morales L.S., Bautista D.E.H. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavange L.M., Kalsbeek W.D., Sorlie P.D. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Ann. Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Probst J.C., Harun N., Bennett K.J., Torres M.E. Acculturation, physical activity, and obesity among Hispanic adolescents. Ethn. Health. 2009;14(5):509–525. doi: 10.1080/13557850902890209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lora C.M., Daviglus M.L., Kusek J.W. Chronic kidney disease in United States Hispanics: a growing public health problem. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4):466–472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lora C.M., Gordon E.J., Sharp L.K., Fischer M.J., Gerber B.S., Lash J.P. Progression of CKD in Hispanics: potential roles of health literacy, acculturation, and social support. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):282–290. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G., Sabogal F., Marin B.V., Otero-Sabogal R., Perez-Stable E.J. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Moran A., Diez Roux A.V., Jackson S.A. Acculturation is associated with hypertension in a multiethnic sample. Am. J. Hypertens. 2007;20(4):354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris K., Nissenson A.R. Race, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in CKD in the United States. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1261–1270. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortman J., Velkoff V., Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

- Pérez-Escamilla R. Dietary quality among Latinos: is acculturation making us sick? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009;109(6):988–991. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla R., Putnik P. The role of acculturation in nutrition, lifestyle, and incidence of type 2 diabetes among Latinos. J. Nutr. 2007;137(4):860–870. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas J.J., Abdelbary B., Rentfro A., Fisher-Hoch S., McCormick J. Cardiovascular disease risk among the Mexican American population in the Texas-Mexico border region, by age and length of residence in United States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11 doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis J.M., Marks G., Garcia M., Shelton D. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: findings from HHANES 1982-84. Am. J. Public Health. 1990;80(Suppl):11–19. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie P.D., Avilés-Santa L.M., Wassertheil-Smoller S. Design and implementation of the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Ann. Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamer M., Richard C., Casebeer A.W., Ray N.F. Health insurance coverage among foreign-born US residents: the impact of race, ethnicity, and length of residence. Am. J. Public Health. 1997;87(1):96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmins C.L. The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47(2):80–96. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(02)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Renal Data System . Vol. 2. 2015. USRDS Annual Data Report.https://www.usrds.org/2015/download/vol2_USRDS_ESRD_15.pdf End-stage Renal Disease - vol2_USRDS_ESRD_15.pdf. (Published October 24, 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Williams M.V., Parker R.M., Baker D.W. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA. 1995;274(21):1677–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M.V., Baker D.W., Honig E.G., Lee T.M., Nowlan A. Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest. 1998;114(4):1008–1015. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material