Abstract

Background

Electrical injuries represent life-threatening emergencies. Evidence on differences between high (HVI) and low voltage injuries (LVI) regarding characteristics at presentation, rhabdomyolysis markers, surgical and intensive burn care and outcomes is scarce.

Methods

Consecutive patients admitted to two burn centers for electrical injuries over an 18-year period (1998–2015) were evaluated. Analysis included comparisons of HVI vs. LVI regarding demographic data, diagnostic and treatment specific variables, particularly serum creatinine kinase (CK) and myoglobin levels over the course of 4 post injury days (PID), and outcomes.

Results

Of 4075 patients, 162 patients (3.9%) with electrical injury were analyzed. A total of 82 patients (50.6%) were observed with HVI. These patients were younger, had considerably higher morbidity and mortality, and required more extensive burn surgery and more complex burn intensive care than patients with LVI. Admission CK and myoglobin levels correlated significantly with HVI, burn size, ventilator days, surgical interventions, amputation, flap surgery, renal replacement therapy, sepsis, and mortality. The highest serum levels were observed at PID 1 (myoglobin) and PID 2 (CK). In 23 patients (14.2%), cardiac arrhythmias were observed; only 4 of these arrhythmias occurred after hospital admission. The independent predictors of mortality were ventilator days (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.06–1.51, p = 0.009), number of surgical interventions (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.27–0.834, p = 0.010) and limb amputations (OR 14.26, 95% CI 1.26–162.1, p = 0.032).

Conclusions

Patients with electrical injuries, HVI in particular, are at high risk for severe complications. Due to the need for highly specialized surgery and intensive care, treatment should be reserved to burn units. Serum myoglobin and CK levels reflect the severity of injury and may predict a more complex clinical course. Routine cardiac monitoring > 24 h post injury does not seem to be necessary.

Keywords: Electrical injury, Burns, High voltage, Creatinine kinase, Myoglobin, Amputation

Background

Electrical injuries are rare but potentially life-threatening emergencies. Voltage exposure is defined by industrial norms as either above or below 1000 V (high voltage injuries (HVI) or low voltage injuries (LVI), respectively) [1]. The cutoff value of 1000 V is not supported by clinical data, and LVI may cause similar damage to the human body as HVI, depending on individual current pathways, amperage and the duration of current exposure. Usually, HVI causes high temperatures in tissues of greater electrical resistance, leading to extensive deep tissue injuries and microvascular coagulation, whereas LVI causes less invasive tissue lesions but is more likely to induce malignant cardiac arrhythmia and higher rates of neurologic long-term sequelae [1–8]. HVI and LVI may both account for complex neurovascular lesions. Clinical symptoms may be considerably delayed and often require repetitive surgery. Additionally, extensive muscular necrosis and rhabdomyolysis may lead to acute kidney injury (AKI), coagulation disorders, compartment syndrome and amputation [1–3]. The goal of this study was to explore differences in prehospital care, admission characteristics, burn intensive care, surgery and outcomes in patients requiring admission to a burn intensive care unit (BICU) after HVI and LVI.

Methods

After approval of the local ethics committees, the databases of two neighboring burn centers in Central Germany were reviewed in order to identify patients who were admitted to the BICU for the treatment of electrical injuries between 01/1998 and 12/2015. Electrical injuries were defined as direct electrical injuries, electric arc burns and concomitant burns due to HVI or LVI. Both centers were comparable regarding infrastructure, staff and adherence to national recommendations. The catchment areas of both centers are coordinated by the regional emergency dispatching services and by the national burn depository of the fire dispatching center of the City of Hamburg. The distance of the two burn centers is 40 km and together, they have a catchment area of 3 federal states involving approximately 8.5 million inhabitants. The burn center in Leipzig provides six BICU beds and six intermediate care beds whereas the burn center in Halle provides eight BICU beds.

General management

Patients were admitted to the burn resuscitation room from the trauma scene or were secondarily transferred from other hospitals. The indications for BICU admission comprised surgical burn wound management, potential risk for rhabdomyolysis and cardiac arrhythmia. Emergency measures included tracheal intubation in case of progressive airway edema or respiratory insufficiency, central venous and arterial access, urinary catheterization, electrocardiography and cardiac monitoring. If HVI compromised limb circulation, pulse oximetry was routinely applied to detect peripheral perfusion deficits. In cases of progressive edema and compartment syndrome, decompression escharotomy or fasciotomy was performed immediately. Fluid resuscitation was initiated using lactated or acetated Ringer’s solution according to Parkland formulas and target urinary outputs of 0.5 ml/kg/h. A more aggressive approach (estimating a urinary output of 2 ml/kg/h) was performed in the presence of relevant myoglobinemia (serum myoglobin level > 1000 μg/l). Application of diuretics was avoided within the first 24 h. Pharmacological strategies, such as application of mannitol or alkalization by adding sodium bicarbonate to the intravenous solution, were not performed routinely but were considered in cases with severe rhabdomyolysis (serum myoglobin > 3000 μg/l). Renal replacement therapy (RRT) was initiated only in manifest AKI using continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) or continuous veno-venous hemodialysis (CVVHD). Additional vasopressors were used in order to maintain mean arterial blood pressures > 70 mmHg to provide tissue oxygenation and avoid extensive fluid creep. Necrosectomy and split thickness skin grafting were performed within 72 h after admission, depending on the patient’s individual condition. Limb amputation and microvascular tissue transplantation were performed in extensive muscle necrosis according to the treatment protocols of the burn centers.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and counts (percentage). Statistical comparisons between survivors and non-survivors were performed using the χ2 test for qualitative data and Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U-test for quantitative data. The alpha level of significance (p) was set at 0.05. All tests were two-tailed. Univariate analysis was performed to identify possible predictors of mortality. Variables tested included demographic data, burned total body surface area (TBSA), emergency airway management, cardiac arrhythmia electrocardiography and time, admission temperature, serum myoglobin, creatine kinase (CK) and troponin levels over the course of four PID, intensive care, surgical procedures and outcomes. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of mortality. Data were obtained from paper-based and electronic charts.

Results

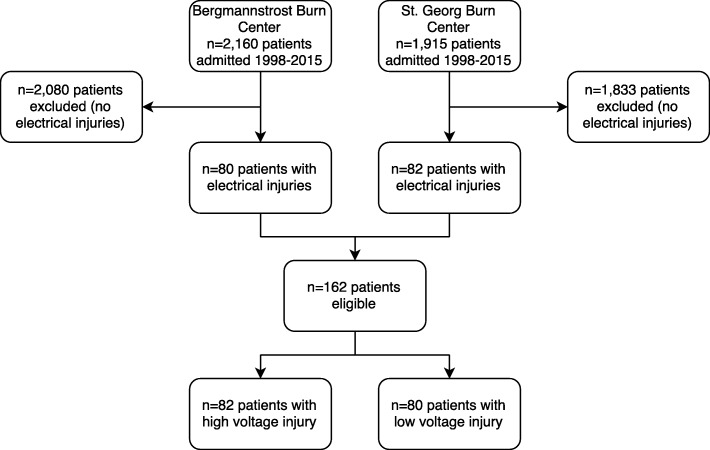

During the study period, 4075 patients were admitted to the two BICUs; 162 (3.9%) of these patients met the inclusion criteria and thus were subject of the study (Fig. 1). Of the 162 patients, 11 patients (6.8%) were aged below 18 years (range 12–17 years). HVI was present in 82 patients (50.6%) (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Most patients were male (94.4%), and the mean age was 37.7 ± 15.5 years (Table 1). Emergency tracheal intubation was required in 74 patients (45.6%) (Table 2). The need for tracheal intubation was significantly associated with mortality (p < 0.001). Cardiac arrhythmia was observed in 23 patients (14.2%), including seven patients who required cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) at the scene of whom five survived until BICU discharge to rehabilitation (Table 1). Four patients (2.5%) presented cardiac arrhythmias after hospital admission. All arrhythmias were self-limiting without compromising the patient. In one patient, arrhythmia attributable to the electric injury was observed > 24 h after admission. HVI patients required significantly more extensive burn intensive care and surgery than LVI patients (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

Table 1.

Demography, clinical presentation, cardiac arrhythmia and trauma context of patients with electric injury

| Total (n = 162) | > = 1000 V (n = 82) | < 1000 V (n = 80) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years; mean (SD) | 37.74 (15.52) | 32.76 (15.19) | 42.85 (14.21) | < 0.001 |

| Male; n (%) | 153 (94.4) | 77 (93.9) | 76 (95.0) | 0.760 |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| % TBSA burned; mean (SD) | 16.0 (18.77) | 25.93 (21.34) | 5.85 (6.67) | < 0.001 |

| ABSI; mean (SD) | 5.21 (2.29) | 6.32 (2.44) | 4.08 (1.40) | < 0.001 |

| Inhalation injury; n (%) | 13 (8.0) | 10 (12.2) | 3 (3.8) | 0.048 |

| Admission temperature, °C; mean (SD) | 35.67 (1.32) | 35.17 (1.59) | 36.18 (.67) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 0.209 | |||

| On scene; n (%) | 18 (11.1) | 11 (13.4) | 7 (8.8) | |

| EMS transport; n (%) | 1 (.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | |

| BICU < 24 h; n (%) | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.8) | |

| BICU > 24 h; n (%) | 1 (.6) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 0.124 | ||||

| Extrasystole/ST/AF; n (%) | 9 (5.6) | 2 (2.4) | 7 (8.8) | |

| VT/VF; n (%) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Asystole/PEA; n (%) | 4 (2.5) | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Trauma context; n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Work | 105 (64.8) | 43 (52.4) | 62 (77.5) | |

| Non-work | 48 (29.6) | 31 (24.3) | 17 (23.7) | |

| Suicide attempt | 9 (5.6) | 8 (9.8) | 1 (1.3) | |

SD standard deviation, TBSA total body surface area, ABSI abbreviated burn severity index, EMS emergency medical service, BICU burn intensive care unit, ST/AF sinus tachycardia/atrial fibrillation, VT/VF ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation, PEA pulseless electric activity

italicized p values indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

Table 2.

Emergency tracheal intubation, surgery, burn intensive care, and outcomes of patients with electric injury

| Total (n = 162) | > = 1000 V (n = 82) | < 1000 V (n = 80) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency tracheal Intubation | < 0.001 | |||

| On scene EMS; n (%) | 60 (37.0) | 53 (64.6) | 7 (8.8) | |

| Resuscitation room; n (%) | 14 (8.6) | 8 (9.8) | 6 (7.5) | |

| Surgery | ||||

| Interventions; mean (SD) | 2.77 (3.28) | 4.07 (3.70) | 1.44 (2.10) | < 0.001 |

| Fasciotomy; n (%) | 29 (17.9) | 27 (32.9) | 2 (2.5) | < 0.001 |

| Split thickness skin graft; n (%) | 116 (71.6) | 71 (86.6) | 45 (56.3) | < 0.001 |

| Flap surgery; n (%) | 24 (14.8) | 18 (22.0) | 6 (7.5) | 0.010 |

| Minor limb amputation; n (%) | 23 (14.2) | 21 (25.6) | 2 (2.5) | < 0.001 |

| Major limb amputation; n (%) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Decompression laparotomy; n (%) | 5 (3.1) | 5 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.025 |

| Burn intensive care | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation; n (%) | 71 (43.8) | 59 (72.0) | 12 (15.0) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator days; mean (SD) | 3.89 (8.98) | 6.83 (10.96) | 0.88 (4.79) | < 0.001 |

| Prone positioning/Rotorest®; n (%) | 13 (8.0) | 12 (14.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0.002 |

| Renal replacement therapy; n (%) | 18 (11.1) | 17 (20.7) | 1 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

| Sepsis; n (%) | 31 (19.1) | 26 (31.7) | 5 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Outcome | ||||

| LOS BICU, days; mean (SD) | 20.98 (20.54) | 29.49 (22.62) | 12.25 (13.52) | < 0.001 |

| 30-day mortality; n (%) | 11 (6.8) | 11 (13.4) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital mortality; n (%) | 17 (10.5) | 15 (18.3) | 2 (2.5) | < 0.001 |

SD standard deviation, EMS emergency medical service, LOS length of stay, BICU burn intensive care unit

italicized p values indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

Table 3.

Admission characteristics of patients with electrical injury

| Total (n = 162) | > = 1000 V (n = 82) | < 1000 V (n = 80) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BICU admission; n (%) | 0.950 | |||

| From scene | 111 (68.5) | 56 (68.3) | 55 (68.8) | |

| Interfacility | 51 (31.5) | 26 (31.7) | 25 (31.3) | |

| EMS vehicle; n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Ground ambulance | 92 (56.8) | 34 (41.5) | 58 (72.5) | |

| Helicopter rescue | 70 (43.2) | 48 (58.5) | 22 (27.5) | |

| BICU admission time after injury; n (%) | 0.774 | |||

| < 1 h | 29 (17.9) | 16 (19.5) | 13 (16.3) | |

| 1-4 h | 107 (66.0) | 53 (64.6) | 54 (67.5) | |

| 4-8 h | 18 (11.1) | 10 (12.2) | 8 (10.0) | |

| 8-24 h | 4 (2.5) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.5) | |

| 24-48 h | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) | |

| > 48 h | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) | |

| BICU distance to scene, km; mean (SD) | 78.08 (62.29) | 83.67 (62.29) | 72.36 (71.02) | < 0.001 |

BICU burn intensive care unit, EMS Emergency medical service

italicized p values indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

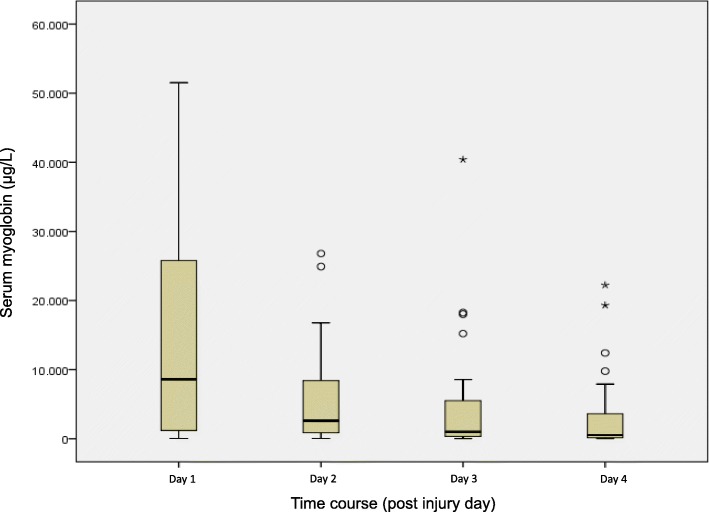

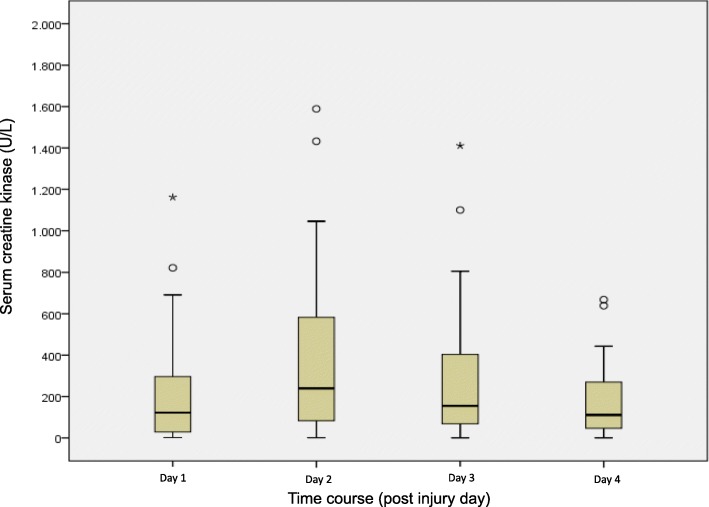

Admission serum myoglobin and CK levels were significantly associated with HVI, TBSA, BICU length of stay (LOS), ventilator days, number of interventions, mortality, amputation, flap surgery, RRT, and sepsis (p < 0.001). In HVI, the highest serum levels were measured at PID 1 (myoglobin) and PID 2 and 3 (CK) (Figs. 2 and 3). Troponin values were associated with HVI, mortality, flap surgery, RRT and sepsis but not with limb amputation or cardiac arrhythmia.

Fig. 2.

Boxplots of serum myoglobin values of high voltage injury patients. In the boxes, the dark horizontal line represents the median, with the box representing the 25th and 75th percentiles, the whiskers the 5th and 95th percentiles, the circles the outliers, and extreme outliers (three times the height of the boxes) represented by asterisks

Fig. 3.

Boxplots of serum creatine kinase values of high voltage injury patients. In the boxes, the dark horizontal line represents the median, with the box representing the 25th and 75th percentiles, the whiskers the 5th and 95th percentiles, the circles the outliers, and extreme outliers (three times the height of the boxes) represented by asterisks

HVI patients required significantly longer BICU LOS, more ventilator days and had a higher incidence of sepsis and RRT and significantly increased 30-day and hospital mortality (p < 0.001) than LVI (Table 2). Logistic regression analysis identified ventilator days (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.06–1.51, p = 0.009), number of surgical interventions (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.27–0.834, p = 0.010) and limb amputations (OR 14.26, 95% CI 1.26–162.1, p = 0.032) as independent predictors of mortality of HVI and LVI (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for mortality/independent predictors

| Parameter | OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 2.25 | 0.24 | 21.20 | 0.479 |

| Voltage (kV) | 0.33 | 0.02 | 6.92 | 0.477 |

| Intubation on scene | 3.56 | 0.22 | 57.16 | 0.370 |

| Ventilator days | 1.27 | 1.06 | 1.51 | 0.009 |

| Age (years) | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.15 | 0.330 |

| Admission temperature (°C) | 0.99 | 0.51 | 1.95 | 0.990 |

| ABSI score (points) | 1.13 | 0.42 | 3.00 | 0.812 |

| TBSA burned (%) | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.27 | 0.111 |

| Interventions | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.83 | 0.010 |

| Limb amputation | 14.26 | 1.26 | 162.1 | 0.032 |

ABSI abbreviated burn severity index, TBSA total body surface area, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

italicized p values indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

Discussion

In our dual center study, electrical injuries accounted for a relatively low 3.9% proportion of BICU admissions, which is in line with the results of a recent literature review that estimated an incidence of below 5% [1]. The results of our study show that patients suffering from HVI show significantly higher morbidity and mortality rates than low voltage victims. Patients with HVI required more extensive burn surgery and more complex burn intensive care, which confirms the findings of previous studies [1–3, 7, 9]. Independent predictors of mortality of electrical injury (both HVI and LVI) were respirator days, number of surgical interventions, and incidence of amputation. In contrast to our results, other studies observed even higher mortality rates in LVI patients than in patients with high voltage trauma. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that these studies included patients with fatal outcomes at the accident site, which may be related to initial cardiac arrhythmia and subsequent arrest. Consequently, LVI should not be under-estimated [1].

In the literature, most electrical injuries were observed in work-related accidents [1, 2, 4, 7]. This finding was also observed in our study, where two-thirds of the patients had work-related injuries. Interestingly, non-work-related injuries had a significantly higher proportion of HVI (Table 1). This subgroup of patients included mainly younger patients who had accidents at railway areas (“train surfing” and other illegal activities). Studies of acute prehospital emergency approaches to patients with electrical injuries are scarce. We observed that patients suffering from HVI were more frequently admitted via helicopter rescue (Table 3), which was probably due to longer distances to the burn centers and more complex injury patterns (higher rates of tracheal intubation at the scene); however, the incidence of prehospital cardiac arrhythmia in HVI patients was comparable to that of LVI patients. Cardiac arrhythmia after BICU admission was observed in only 2.5% of our patients, all of which were self-limiting and did not require intervention. This result may support previous studies, which suggested that prolonged cardiac monitoring after electrical injuries, particularly LVI, is not required [8, 10, 11]. Moreover, other studies found that left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac injury were uncommon and not associated with serum troponin and CK in patients after HVI [12, 13]. A new marker of cardiac injury after electrical injury might be brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), whereas prospective studies regarding the diagnostic accuracy and independence of confounding factors are currently not available [14].

Particularly in HVI, rhabdomyolysis markers, such as serum myoglobin and CK, were associated with injury severity, RRT rate, amputation rate and mortality, as published previously [1–3, 15–19]. The highest myoglobin level was observed at BICU admission with a linear decrease in contrast to the course of CK, which increased until day 2 and 3 after BICU admission until its decrease. Thus, in contrast to myoglobin, CK on admission may not adequately reflect the severity of injury. One study on 37 HVI patients found that the CK serum concentration peaked on the second and third day following injury, whereas the highest CK measurements were obtained in patients with burn sizes of 21 to 40% TBSA. In contrast, patients with more extensive TBSA showed the highest CK levels on the day of admission, which subsequently decreased over the following days. In all patients with TBSA > 41%, serum levels decreased no later than the third day following injury and reached almost physiologic values within 1 week [18]. Other studies found a linear decrease of CK levels in all patients after HVI [19, 20]. To what extent the delay in CK increase is related to burn size or other factors is still debatable. However, the delay might be based on an enzyme-dependent activation characteristic, which is probably associated with latency in response to muscle tissue degeneration due to burns and cellular hydrops. Future studies should address this phenomenon to clarify underlying pathomechanisms. Moreover, it would be interesting to investigate first, whether rhabdomyolysis is influenced by early therapeutic measures (e.g., fasciotomy and/or burn wound excision) and second, whether different strategies of rhabdomyolysis therapy influence outcomes. The common treatment includes aggressive fluid resuscitation and adjuvant application of mannitol and bicarbonate for AKI prevention [21, 22]. However, randomized controlled trials regarding the benefit of both fluids and adjuvant pharmacological therapies are not available and clinical studies provided inconsistent results [21]. The role of continuous RRT remains unclear. In our patients, RRT was not used in an attempt to avoid AKI but only in cases of manifest AKI. A meta-analysis revealed insufficient evidence to discern any benefits of RRT over conventional therapy in the prevention of rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI [23]. In a small study on burn patients, myoglobin elimination myoglobin by RRT using a standard filter was not greater than that by fluid resuscitation alone [24]. However, some studies suggest the early use of newer membranes, such as AN69 ST150, to eliminate myoglobin [25, 26]. Recently, the application of novel cytokine adsorbers for myoglobin removal was proposed [27]. A prospective, randomized, non-blinded, controlled study on this topic is currently underway [28].

Although our data revealed that rhabdomyolysis was associated with the need for amputation and that amputation independently predicted mortality, other studies found that the need for amputation was not associated with increased mortality [29, 30]. Furthermore, one study found that the need for amputation was not associated with increasing burn size [9]. The reasons for these contradictory findings may be different patterns of injury, different thresholds and timings of amputation, and different infrastructures to perform limb salvage using microvascular tissue transplantation. The reliability of prognostic parameters after electrical injury should be interpreted with caution and in regard to the individual course and context of the case.

The current study has some strengths. Due to the long study period and the dual center design, we were able to include a relevant number of patients with reduced center-specific aspects. Our analysis allows us to form statements on the epidemiology and treatment of electrical injuries in a mid-European country. Many studies on electrical injuries have been conducted in considerably different health care systems, where the incidence, management and outcomes of electrical injuries may not be comparable [1]. The long study period and retrospective study design also represent a limitation of the current study. We cannot disclose whether therapy strategies were influenced by the implementation of new guidelines (e.g., introduction of low tidal volume ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome management, avoidance of fluid creep and secondary abdominal compartment syndrome in large burns, and improved sedation management) and/or changes in the departments’ administrative positions during the 18-year study period [31–34]. Furthermore, simultaneous concomitant injuries (e.g., falls from railway pylons) were not analyzed in this study, which could have influenced outcomes. However, although well-powered prospective randomized controlled studies in patients with electrical injuries would be desirable, there are many confounders that may not be addressed appropriately in these settings because of low incidence, incalculably high variability of current exposure, extension of burned TBSA, and predisposing morbidity.

Conclusions

Our data consistently confirm the results of previous studies supporting the need for specialized burn intensive care after electrical injury. Particularly in HVI, life-threating complications may occur. A high proportion of these patients need complex surgical interventions (e.g., microvascular tissue transplantation). Serum myoglobin and CK levels reflect the severity of injury and may predict a more complex clinical course. The delayed onset of CK peak levels after HVI needs to be investigated in further studies. Routine cardiac monitoring > 24 h post injury does not seem to be necessary.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this study were presented at the 1st Central German Burns Symposium (1. Mitteldeutsches Verbrennungssymposium) on June 11, 2016, in Bad Klosterlausnitz, Germany.

Funding

There was no funding for this study. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and University of Leipzig within the program of Open Access Publishing.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABSI

Abbreviated burn severity index

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BICU

Burn intensive care unit

- BNP

Brain natriuretic peptide

- CI

Confidence interval

- CK

Creatine kinase

- CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CT

Computed tomography

- CVVHD

Continuous veno-venous hemodialysis

- CVVHDF

Continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration

- ED

Emergency department

- EMS

Emergency medical service

- HVI

High voltage injury

- LOS

Length of stay

- LVI

Low voltage injury

- OR

Odds ratio

- PEA

Pulseless electric activity

- PID

Post injury day

- RRT

Renal replacement therapy

- SD

Standard deviation

- TBSA

Total body surface area

Authors’ contributions

JG and MFS carried out the study design, performed the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. MFS drafted the manuscript. TS conceived of the study and performed the statistical analysis. AD, DE, PHC, TK, TR, BR, AS, FS, and MS conceived of the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The need for ethical approval was waived by the Ethical Review Board of the Medical Association of Saxony-Anhalt, Halle, Germany, (project ID 75/17) and by the Ethical Review Board of the Medical Association of Saxony, Dresden, Germany (project ID EK-BR-15/12–1). Consent to participate was not applicable due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

The need for informed consent was waived by the Ethical Review Boards of both study centers.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jochen Gille, Email: jochen.gille@sanktgeorg.de.

Thomas Schmidt, Email: thomas.schmidt@bergmannstrost.de.

Adrian Dragu, Email: adrian.dragu@uniklinikum-dresden.de.

Dimitri Emich, Email: dimitri.emich@sanktgeorg.de.

Peter Hilbert-Carius, Email: peter.hilbert@bergmannstrost.de.

Thomas Kremer, Email: thomas.kremer@sanktgeorg.de.

Thomas Raff, Email: thomas1449@web.de.

Beate Reichelt, Email: beate.reichelt@bergmannstrost.de.

Apostolos Siafliakis, Email: siafliakis@hotmail.com.

Frank Siemers, Email: frank.siemers@bergmannstrost.de.

Michael Steen, Email: m.steen.leipzig@web.de.

Manuel F. Struck, Email: manuelstruck@web.de

References

- 1.Shih JG, Shahrokhi S, Jeschke MG. Review of adult electrical burn injury outcomes worldwide: an analysis of low-voltage vs high-voltage electrical injury. J Burn Care Res. 2017;38:e293–e298. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnoldo BD, Purdue GF, Kowalske K, Helm PA, Burris A, Hunt JL. Electrical injuries: a 20-year review. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:479–484. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000144536.22284.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koumbourlis AC. Electrical injuries. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(Suppl 11):S424–S430. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singerman J, Gomez M, Fish JS. Long-term sequelae of low-voltage electrical injury. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:773–777. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318184815d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussmann J, Kucan JO, Russell RC, Bradley T, Zamboni WA. Electrical injuries--morbidity, outcome and treatment rationale. Burns. 1995;21:530–535. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00037-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chudasama S, Goverman J, Donaldson JH, van Aalst J, Cairns BA, Hultman CS. Does voltage predict return to work and neuropsychiatric sequelae following electrical burn injury? Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:522–525. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181c1ff31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kym D, Seo DK, Hur GY, Lee JW. Epidemiology of electrical injury: differences between low- and high-voltage electrical injuries during a 7-year study period in South Korea. Scand J Surg. 2015;104:108–114. doi: 10.1177/1457496914534209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldmann V, Narayanan K, Combes N, Marijon E. Electrical injury. BMJ. 2017;357:j1418. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maghsoudi H, Adyani Y, Ahmadian N. Electrical and lightning injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:255–261. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0B013E318031A11C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Searle J, Slagman A, Maaß W, Möckel M. Cardiac monitoring in patients with electrical injuries. An analysis of 268 patients at the Charité Hospital. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:847–853. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen SM, Riahi S, Hjortshøj S, Mortensen R, Køber L, Søgaard P, et al. Mortality and risk of cardiac complications among immediate survivors of accidental electric shock: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015967. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Cho GY, Kim MK, Park WJ, Kim JH, Lim HE, et al. Alterations in left ventricular function assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography and the clinical utility of cardiac troponin I in survivors of high-voltage electrical injury. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1282–1287. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819c3a83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnoldo B, Klein M, Gibran NS. Practice guidelines for the management of electrical injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:439–447. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000226250.26567.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orak M, Ustündağ M, Güloğlu C, Gökhan S, Alyan O. Relation between serum pro-brain natriuretic peptide, myoglobin, CK levels and morbidity and mortality in high voltage electrical injuries. Intern Med. 2010;49:2439–2443. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safari S, Yousefifard M, Hashemi B, Baratloo A, Forouzanfar MM, Rahmati F, et al. The value of serum creatine kinase in predicting the risk of rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016;20:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s10157-015-1204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handschin AE, Vetter S, Jung FJ, Guggenheim M, Künzi W, Giovanoli P. A case-matched controlled study on high-voltage electrical injuries vs thermal burns. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30:400–407. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181a289a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saracoglu A, Kuzucuoglu T, Yakupoglu S, Kilavuz O, Tuncay E, Ersoy B, et al. Prognostic factors in electrical burns: a review of 101 patients. Burns. 2014;40:702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopp J, Loos B, Spilker G, Horch RE. Correlation between serum creatinine kinase levels and extent of muscle damage in electrical burns. Burns. 2004;30:680–683. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsueh YY, Chen CL, Pan SC. Analysis of factors influencing limb amputation in high-voltage electrically injured patients. Burns. 2011;37:673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vierhapper MF, Lumenta DB, Beck H, Keck M, Kamolz LP, Frey M. Electrical injury: a long-term analysis with review of regional differences. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66:43–46. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181f3e60f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chavez LO, Leon M, Einav S, Varon J. Beyond muscle destruction: a systematic review of rhabdomyolysis for clinical practice. Crit Care. 2016;20:135. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1314-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:62–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng X, Zhang L, Wu T, Fu P. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) for rhabdomyolysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD008566. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008566.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stollwerck PL, Namdar T, Stang FH, Lange T, Mailänder P, Siemers F. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure in severely burned patients. Burns. 2011;37:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amyot SL, Leblanc M, Thibeault Y, Geadah D, Cardinal J. Myoglobin clearance and removal during continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1169–1172. doi: 10.1007/s001340051031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potier J. Feasibility between AN69 and hemodiafiltration online. Nephrol Ther. 2010;6:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiegele M, Krenn CG. Cytosorb™ in a patient with legionella-pneumonia associated rhabdomyolysis. ASAIO J. 2015;61:e14–e16. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02111018 Extracorporeal Therapy for the Removal of Myoglobin Using the CytoSorb in Patients With Rhabdomyolysis. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02111018 accessed 15 Jan 2018.

- 29.Ghavami Y, Mobayen MR, Vaghardoost R. Electrical burn injury: a five-year survey of 682 patients. Trauma Mon. 2014;19:e18748. doi: 10.5812/traumamon.18748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarim A, Ezer A. Electrical burn is still a major risk factor for amputations. Burns. 2013;39:354–357. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pruitt BA., Jr Protection from excessive resuscitation: “pushing the pendulum back”. J Trauma. 2000;49(3):567–568. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200009000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrence A, Faraklas I, Watkins H, Allen A, Cochran A, Morris S, et al. Colloid administration normalizes resuscitation ratio and ameliorates “fluid creep”. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:40–47. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181cb8c72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1471–1477. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.