Significance

Elucidating how different types of presynaptic inputs to a brain area are functionally organized is crucial for understanding how incoming information is integrated. Here, we introduce presynaptic-targeted genetically encoded calcium indicators in two colors and mapped the functional organization of two major input pathways—primary visual cortex (V1) intrinsic and V2–V1 feedback—to tree shrew V1. Axon boutons of both input pathways are spatially organized according to their orientation preferences, forming orientation maps aligned to the V1 map. Nonselective integration of intrinsic inputs around dendritic trees reproduced neuronal orientation preference, suggesting a reinforcing role for intrinsic inputs to the neuronal map. Beyond the specific findings, the experimental approaches we introduced here could significantly expand the toolbox for exploring the organization of neural circuits.

Keywords: primary visual cortex, presynaptic inputs, dual-color calcium imaging, orientation selectivity, visual circuitry

Abstract

In the primary visual cortex (V1) of many mammalian species, neurons are spatially organized according to their preferred orientation into a highly ordered map. However, whether and how the various presynaptic inputs to V1 neurons are organized relative to the neuronal orientation map remain unclear. To address this issue, we constructed genetically encoded calcium indicators targeting axon boutons in two colors and used them to map the organization of axon boutons of V1 intrinsic and V2–V1 feedback projections in tree shrews. Both connections are spatially organized into maps according to the preferred orientations of axon boutons. Dual-color calcium imaging showed that V1 intrinsic inputs are precisely aligned to the orientation map of V1 cell bodies, while the V2–V1 feedback projections are aligned to the V1 map with less accuracy. Nonselective integration of intrinsic presynaptic inputs around the dendritic tree is sufficient to reproduce cell body orientation preference. These results indicate that a precisely aligned map of intrinsic inputs could reinforce the neuronal map in V1, a principle that may be prevalent for brain areas with function maps.

Neurons in the brain are often spatially organized into topographic maps according to their response properties. In the primary visual cortex (V1) of many highly visual mammalian species, neurons that respond to visual signals of similar orientations are spatially clustered into iso-orientation domains. Such iso-orientation domains are arranged circularly, with their preferred orientations shifting in a graded manner, around singularities known as pinwheel centers (1–4). The neural mechanism underlying the emergence of such pinwheel-like orientation maps remains to be fully understood.

An important step to elucidate the formation of V1 orientation map is to determine whether and how the different types of inputs received by V1 neurons are functionally organized. Besides feedforward projections from the lateral geniculate nucleus, V1 neurons receive major inputs from intrinsic connections originating from other V1 neurons, as well as feedback projections from higher visual cortical areas such as V2. By tracing the axon projections originating from neurons located at a single site, previous works showed that both V1 horizontal and V2–V1 feedback axon boutons are clustered and biased to columns with similar preferred orientation in a “like-to-like” manner (5–8). Such studies, however, have not directly addressed the question of how axon projections originating from different sites are organized when they converge to a common target area, a central question from the postsynaptic perspective because each V1 neuron integrates inputs from thousands of presynaptic axon boutons. If the axon boutons are spatially organized according to their origins or response properties, it would result in a functional map of presynaptic inputs that impose specific activity patterns to the postsynaptic spines and influence how dendrites integrate incoming information.

The development of highly sensitive genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) (9–13) has provided a direct method to examine such questions by allowing the measurement of axon bouton responses from specific neural pathways. These indicators have been used to study several long-range projection pathways such as those from V1 to higher visual areas (14, 15), and from lateral geniculate nucleus to V1 (16–18) in rodents, species in which the orientation preference of V1 neurons is semirandomly distributed (19–21). To our knowledge, such an approach has not been introduced to the study of axon projections in highly visual species that show orientation maps, the presence of which suggests more precisely organized presynaptic inputs. Furthermore, calcium indicators used in those previous studies are freely distributed in the cytoplasm and not suitable for imaging axon boutons of local circuits, because signals of axon boutons could not be readily separated from those of bypassing dendrites and axons.

In this study, by constructing GECIs that are designed to target axon boutons specifically, we were able to map the functional organization of the V1 intrinsic and V2–V1 feedback projections in the tree shrew, a species with strong similarities to primates in the organization of visual system (22). We found that axon boutons of both input pathways are organized into orientation maps. Further examination using dual-color calcium imaging showed that the orientation map of V1 intrinsic axon boutons is precisely aligned with the map of V1 cell bodies, whereas that of V2–V1 feedback projections is less well aligned. Nonselective integration of intrinsic presynaptic inputs around the dendritic tree is sufficient to reproduce cell body orientation preference, suggesting that the functional map of intrinsic inputs reinforces the V1 orientation map.

Results

GECIs for Imaging Axon Bouton Activities.

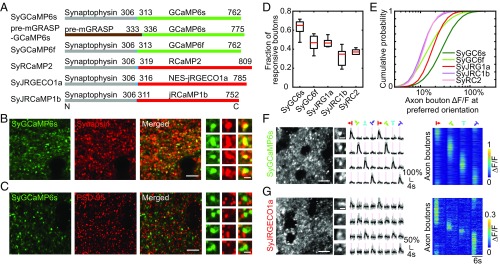

To map the functional organization of the presynaptic inputs to V1 neurons, we attempted to construct GECIs targeting axon boutons to avoid contaminating signals from bypassing dendrites and axons. Following previous reports (23, 24), we fused GCaMP6s to the cytosol side of either the synaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin, or the presynaptic membrane protein pre-mGRASP (Fig. 1A). To test whether these fusion proteins are successfully targeted to axon boutons, we expressed them in mouse V1 through adenoassociated virus (AAV) infection. We found that SyGCaMP6s, the fusion protein between synaptophysin and GCaMP6s, were highly localized as fluorescent puncta with a profile consistent to that of axon boutons, while the fusion protein with pre-mGRASP was not targeted with similar specificity (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). Further immunostaining experiments showed that SyGCaMP6s strongly colocalized with the presynaptic marker synapsin but not with the postsynaptic marker PSD-95, indicating successful targeting to axon boutons (Fig. 1 B and C). Axon boutons expressing SyGCaMP6s exhibited normal morphology, with no change in size compared with control boutons (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

Fig. 1.

Construction and characterization of presynaptic GECIs. (A) Presynaptic GECIs were constructed by fusing calcium indicators to the presynaptic proteins synaptophysin or pre-mGRASP, separated by a short variable-length linker (colored in cyan). Numbers indicate the location of amino acids. (B) Comparison of the expression pattern of SyGCaMP6s with that of synapsin, with example sites illustrating their colocalization shown Far Right. [Scale bars: 5 μm (Left) and 1 μm (Far Right).] (C) Comparison of the expression pattern of SyGCaMP6s with that of PSD-95, with example sites illustrating their adjacent localization shown in the Far Right. [Scale bars: 5 μm (Left) and 1 μm (Far Right).] (D) Fraction of axon boutons responsive to drifting gratings for the presynaptic GECIs constructed. Bottom and top whiskers, Minima and maxima; bottoms and tops of the boxes, first and third quartiles; central lines, medians. Data were from two to three mice for each indicator. (E) Cumulative distribution of ΔF/F at preferred grating orientation for axon boutons expressing the presynaptic GECIs. Abbreviations used in D and E are as follows: SyGC6f, SyGCaMP6f; SyGC6s, SyGCaMP6s; SyJRC1b, SyJRCaMP1b; SyJRG1a, SyJRGECO1a; SyRC2, SyRCaMP2. (F and G) Responses of axon boutons expressing SyGCaMP6s and SyJRGECO1a to drifting gratings in tree shrew V1. (Left) Example images of SyGCaMP6s and SyJRGECO1a fluorescence in vivo. Cell bodies devoid of fluorescence appear as “black holes” in the images. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (Middle) Representative calcium signals from individual axon boutons (scale bar: 2 μm), in response to drifting gratings of different directions. Traces in light gray represent the individual trials, and traces in black represent their averages. The temporal period for stimulus ON is shaded in pink. (Right) Calcium signals from all orientation-selective axon boutons in response to drifting gratings of four different orientations, with each row representing response over time for a single bouton. Boutons were sorted according to their preferred orientations.

Calcium indicators in multiple colors and with different biophysical properties could be flexibly combined for the simultaneous imaging of multiple neuronal populations (10, 25, 26). To expand the toolbox for imaging presynaptic inputs, we targeted several recently reported GECIs [including GCaMP6f (9), RCaMP2 (11), jRGECO1a (10), and jRCaMP1b (10)] to axon boutons, using strategies similar to that used for constructing SyGCaMP6s (Fig. 1A). These indicators showed successful targeting to axon boutons not only when expressed in cortex but also in subcortical structures (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Expression in the cortex of two other mammalian species, macaque monkeys and tree shrews, also resulted in presynaptic targeting (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D). To evaluate the functionality of these indicators in vivo, we expressed them in mouse V1 and compared the visual responses of axon boutons expressing different indicators (Fig. 1 D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The pair of green/red indicators with the best in vivo performance, SyGCaMP6s and SyJRGECO1a, was selected for further examination in tree shrew V1. Similar to results from mouse, both indicators showed robust orientation-selective responses to drifting gratings (Fig. 1 F and G and Movie S1), although the average peak response amplitude of SyJRGECO1a was approximately one-half that of SyGCaMP6s (SyGCaMP6s: ΔF/F = 0.64 ± 0.37; SyJRGECO1a: ΔF/F = 0.32 ± 0.08, mean ± SD). Taken together, these data show that the set of presynaptic-targeting GECIs we constructed are sensitive and specific indicators of axon bouton activity in vivo.

Orientation Map of Axon Boutons of V1 Intrinsic Connections.

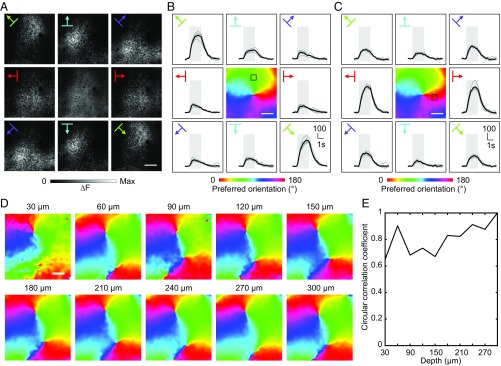

To investigate the functional organization of V1 intrinsic connections in tree shrew, we expressed SyGCaMP6s in a large population of V1 neurons (mostly L2/3 and upper L5, covering ∼10 mm2 by multiple virus injections; SI Appendix, Materials and Methods) and imaged the response patterns of axon boutons in head-fixed awake animals. We imaged the axon boutons at the center of the whole labeled area, ensuring that the sampled boutons included both the local inputs (within 500 μm; ref. 5) and the long-range inputs from more distant locations within the injected area. When we recorded the SyGCaMP6s responses at a lower resolution (1.2 × 1.2 μm2 per pixel) to obtain the large-scale map, where the signal of each pixel may come from multiple axon boutons (as for all of the “large-scale maps” below), we found that calcium signals in different cortical regions showed maximal responses to gratings of distinct orientations (Fig. 2 A–C). To visualize the large-scale orientation map, we calculated the orientation preferences on a pixel-by-pixel basis and colored each pixel according to its preferred orientation determined by vector summation of the stimulus-evoked fluorescence change (1, 2). The orientation map obtained exhibited the stereotypical pinwheel-like structure, where the pinwheel centers were surrounded by iso-orientation domains with preferred orientations shifting in a graded manner (Fig. 2 B and C). Similar orientation maps were found when the same area was mapped at different depths from L1 to L2/3, suggesting that V1 intrinsic connections are functionally organized into vertical columns according to preferred orientation (Fig. 2 D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Large-scale orientation maps of V1 intrinsic inputs. (A) Calcium fluorescence changes (ΔF) of V1 intrinsic axon boutons to drifting gratings of eight directions, mapped at a relatively lower resolution where the signal of each pixel may come from multiple axon boutons, are shown in the outer eight images. Image in the Center shows the anatomical structure obtained by averaging baseline fluorescence. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (B) From the data shown in A, the orientation map was calculated and shown in the Center, with each pixel color coded according to its preferred orientation. ΔF traces for an example region of interest (ROI) (marked with a black box on the orientation map) in response to drifting gratings of different directions are shown in the outer eight images. Traces in gray are results from individual trials, while traces in black represent their mean. The temporal period for stimulus ON is shaded in gray. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (C) Similar to B, except that traces from another ROI (marked with a black box on the orientation map) are shown. (D) Large-scale orientation map of the V1 intrinsic axon boutons at different cortical depths (labeled above each map). (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (E) Similarity between the orientation maps from different depths, quantified by the circular correlation coefficient (48) between each map and the map of the deepest layer (300 μm).

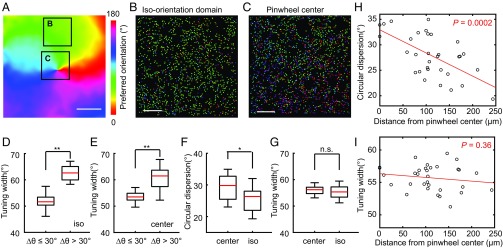

We then imaged selected areas within the large-scale orientation map at a higher spatial resolution (0.2 × 0.2 μm2 per pixel) to examine the fine-scale organization of the orientation preference at the level of individual axon boutons. In total, we examined 53,263 axon boutons from four animals and found 26,908 axon boutons (50%) responding to drifting grating stimuli. Among those, 17,184 (64%) had significant tuning to a specific orientation. Most orientation-selective axon boutons showed preferred orientations similar to nearby boutons and consistent to their locations in the large-scale map, although a substantial percentage of axon boutons at both pinwheel centers and iso-orientation domains showed significant deviations in their preference from that of the large-scale map (Fig. 3 A–C). These axon boutons with significant deviations were also less orientation selective (Fig. 3 D and E, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P < 0.001 for boutons in both iso-orientation domains and pinwheel centers). When the local heterogeneity of the orientation preferences of individual axon boutons was quantified (using the measure of local circular dispersion; SI Appendix, Materials and Methods), we found that iso-orientation domains exhibited lower local heterogeneity than pinwheel centers (average circular dispersion: 25.7 ± 3.7° from 14 iso-orientation domains; 29.5 ± 4.0° from 18 pinwheel centers; mean ± SD; Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.01; Fig. 3F). Furthermore, the level of local heterogeneity decreased with the distance from the pinwheel center (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r = −0.62, P = 0.0002, n = 32 regions; Fig. 3H). By contrast, the sharpness of orientation tuning for individual axon boutons did not correlate with the distance from the pinwheel center (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, P = 0.36, n = 32 regions; Fig. 3 G and I). Together, these results indicate that individual axon boutons of V1 intrinsic connections with similar orientation preference tend to cluster together, forming a large-scale pinwheel-like map with striking similarities to the previously described V1 cell body maps (4, 20, 27, 28).

Fig. 3.

Fine-scale organizations of V1 intrinsic axon boutons. (A) Large-scale orientation map of the region to be analyzed at the resolution of single axon boutons. The two boxes mark the areas visualized at higher resolution in B and C. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (B and C) Individual V1 intrinsic axon boutons in an iso-orientation domain B, and around a pinwheel center C, are colored according to their preferred orientations. Each dot represents an individual orientation-selective axon bouton. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (D and E) Axon boutons showing larger deviations in preferred orientations (Δθ > 30°) are less orientation-selective than boutons showing smaller deviations (Δθ ≤ 30°). **P < 0.01. (F and G) Local heterogeneity measured by average circular dispersion is significantly larger for regions classified as pinwheel centers (center) than those classified as iso-orientation domains (iso). By contrast, no such difference was found for average axon bouton tuning width. Bottom and top whiskers, minima and maxima; bottoms and tops of the boxes, first and third quartiles; central lines, medians. *P < 0.05. (H and I) Average local circular dispersions of the imaged regions significantly correlated to their distances to the nearest pinwheel center, with the fitted line shown in red. By contrast, no such correlation was found for the average tuning width of the axon boutons. n.s., not significant.

The fact that V1 intrinsic inputs are organized into an orientation map clearly suggests that axon boutons surrounding individual dendritic segments should tend to share similar preferred orientations. Indeed, when we visualized the dendrites of single neurons with a red fluorescent protein mRuby2 and characterized the orientation preference of V1 intrinsic axon boutons within a distance of 4 μm to the dendritic segments (length: 51 ± 12 μm, mean ± SD; n = 19 segments), we found that boutons surrounding individual dendritic branches showed a strong bias in the distribution of preferred orientation, with an average circular dispersion of ∼25° (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), similar to that measured from the postsynaptic spines (29). Although the spatial resolution of two-photon microscopy does not allow for the identification of actual synaptic contacts, this result shows that the presynaptic organization of V1 intrinsic axon boutons would strongly favor postsynaptic functional clustering when no specific connectivity rule was assumed.

Precise Alignment of V1 Intrinsic Axon Bouton Map with Cell Body Map.

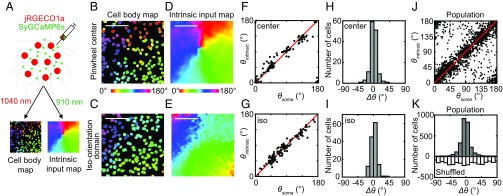

To determine how the orientation map of V1 intrinsic axon boutons is related to the map of V1 cell bodies, we directly compared the two maps using a dual-color calcium imaging approach. V1 cell bodies were labeled with a red calcium indicator jRGECO1a (10), whereas intrinsic axon boutons were labeled with the green indicator SyGCaMP6s as above (Fig. 4A). Spectral cross talk between the green and red channels was eliminated by imaging the two indicators separately at different excitation wavelengths (SI Appendix, Fig. S5; also SI Appendix, Materials and Methods).

Fig. 4.

Dual-color calcium imaging of the orientation maps of V1 cell bodies and intrinsic axon boutons. (A) Illustration of the experiment paradigm. A pair of calcium indicators with different colors and subcellular targets (jRGECO1a: red, entire cytoplasm; SyGCaMP6s: green, axon boutons) is used to measure the orientation map of V1 cell bodies and intrinsic axon boutons at the same regions. (B and C) Orientation maps of V1 cell bodies around a pinwheel center and in an iso-orientation domain mapped with jRGECO1a. Orientation preference is color coded in continuous scale shown below B. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (D and E) Large-scale orientation maps of V1 intrinsic axon boutons mapped with SyGCaMP6s in the same regions as B and C. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (F and G) Comparison between the preferred orientation of every orientation-selective cell body (θsoma) within B and C with that of the intrinsic axon boutons (θintrinsic) surrounding them (within 12 μm). (H and I) Distribution of the difference (Δθ) between θsoma and θintrinsic for every orientation-selective cell body in B and C. (J) Comparison between θsoma and θintrinsic for orientation-selective cell bodies from all of the imaged regions. (K) Distribution of Δθ for all of the imaged regions (Upper) was significantly different from the distribution obtained after random shuffling of cell body locations (Lower).

We found that the red indicator jRGECO1a showed reliable responses to visual stimuli, despite some visible accumulation in lysosome-like structures as previously reported (10) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Out of the 5,371 cell bodies expressing jRGECO1a from four animals, 4,183 neurons (74 ± 8%; n = 4 animals) responded to drifting grating stimuli, and among them 2,140 neurons (39 ± 7%; n = 4) showed statistically significant orientation tuning. The orientation map of the cell bodies exhibited a pinwheel-like structure at the single-cell level (Fig. 4 B and C). Comparison of this cell body map with the large-scale intrinsic axon bouton map showed that the two maps were closely aligned, with pinwheel centers located at the same sites and iso-orientation domains arranged in the same sequences (Fig. 4 B–E). At the single-cell level, the preferred orientation of each cell body (θsoma) strongly correlated with the average preferred orientation of surrounding axon boutons (θintrinsic), in both iso-orientation domains and pinwheel centers (Fig. 4 F, G, and J). The distribution of the difference (Δθ) between θsoma and θintrinsic was centered sharply at zero (−1.1 ± 13°, mean ± SD; n = 2,057 pairs; Fig. 4 H, I, and K), and significantly different from that obtained after random shuffling of cell body locations (two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, P < 10−4). A similar distribution of Δθ (−0.6 ± 13°, mean ± SD; n = 199 pairs) was obtained when we mapped the preferred orientations more precisely using eight orientations instead of four (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Thus, the orientation preferences of V1 cell bodies were closely matched to that of the nearby intrinsic axon boutons, indicating a precise form of like-to-like connectivity that is accurate up to the single-cell level.

Orientation Map of V2–V1 Feedback Projections.

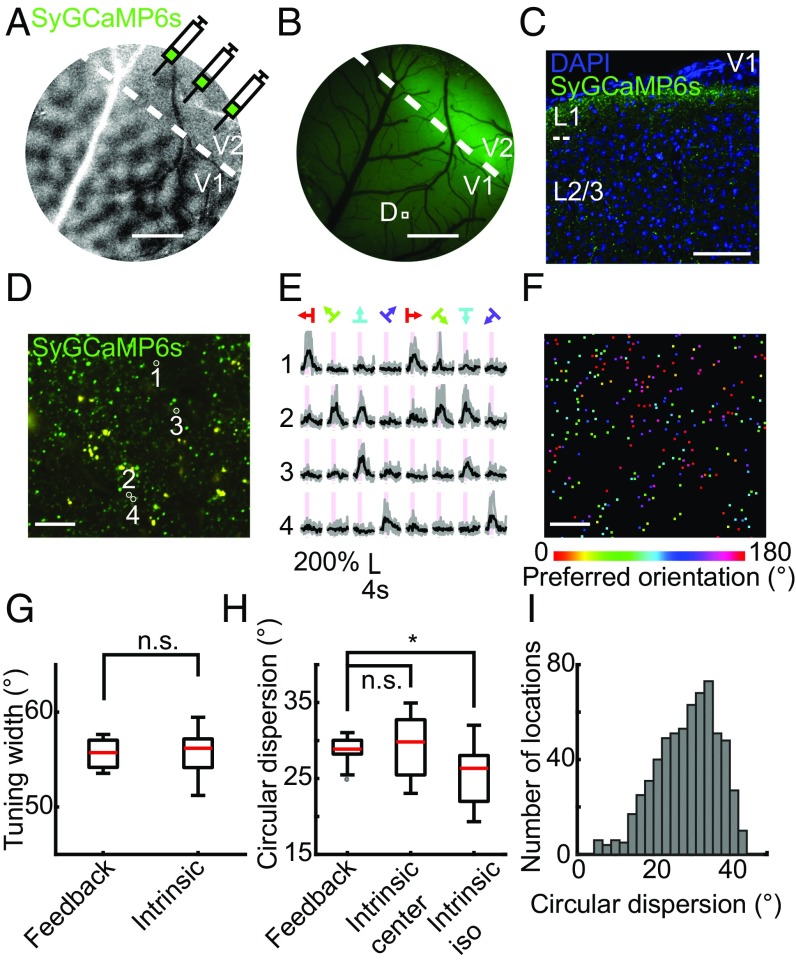

To study the functional organization of V2–V1 feedback projections, we identified the V1/V2 border by imaging intrinsic optical signals (30) and labeled V2–V1 feedback axon boutons by injecting SyGCaMP6s-encoding AAV in a large area of V2 (Fig. 5 A and B). Labeled V2 axon boutons were mainly located at superficial L1 in V1, consistent with previously described laminar distribution of V2–V1 feedback projections (31) (Fig. 5C), and showed reliable responses to drifting gratings (Fig. 5 D–F). Out of 26,005 axon boutons, 9,047 boutons (35%) responded to drifting grating stimuli, among which 5,006 (55%) were significantly tuned to a specific orientation. Both the number of labeled axon boutons and the number of orientation-selective boutons are much larger in L1 than in L2/3, excluding the possibility that significant numbers of V1 axon boutons are unintentionally labeled, through either virus leakage across V1/V2 border or retrograde transport (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Compared with V1 intrinsic axon boutons, the orientation tuning sharpness of V2–V1 feedback axon boutons was similar (Fig. 5G; Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.94, n = 10 and 32 regions for feedback and intrinsic axon boutons), while the local heterogeneity of orientation preference was larger than that of iso-orientation domains and not significantly different from that of pinwheel centers (Fig. 5 H and I; Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.02 for iso-orientation domains and 0.55 for pinwheel centers). This suggests that the axon boutons of V2–V1 feedback projections are less precisely organized than V1 intrinsic axon boutons in their preferred orientations.

Fig. 5.

Orientation map of the V2–V1 feedback axon boutons. (A) Orientation map of the visual cortex obtained by intrinsic imaging to identify the V1/V2 border (dashed line). (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (B) Wide-field fluorescence image of the cortex after expression of SyGCaMP6s in V2. A typical region for imaging V2–V1 feedback axon boutons was marked with a square box and shown at a higher resolution in D. (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (C) V2–V1 feedback axon boutons labeled by SyGCaMP6s were mainly located at superficial L1 of V1. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (D) Example calcium fluorescence image of the V2–V1 feedback axon boutons labeled by SyGCaMP6s from the boxed region in B, with four individual axon boutons marked with circles. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (E) Calcium signals of the four axon boutons circled in D, in response to drifting gratings of different directions. Traces in light gray represent the individual trials, and traces in black represent their averages. The temporal period for stimulus ON is shaded in pink. (F) Preferred orientations of the V2–V1 feedback axon boutons in D. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (G) Average orientation tuning width is not significantly different between V2–V1 feedback and V1 intrinsic axon boutons. (H) Local heterogeneity of V2–V1 feedback axon boutons is significantly larger than that of V1 intrinsic boutons located at iso-orientation domains (Intrinsic iso), but comparable to that of V1 intrinsic boutons located at pinwheel centers (Intrinsic center). *P < 0.05. (I) Distribution of local circular dispersion for V2–V1 feedback axon boutons from all of the locations. n.s., not significant.

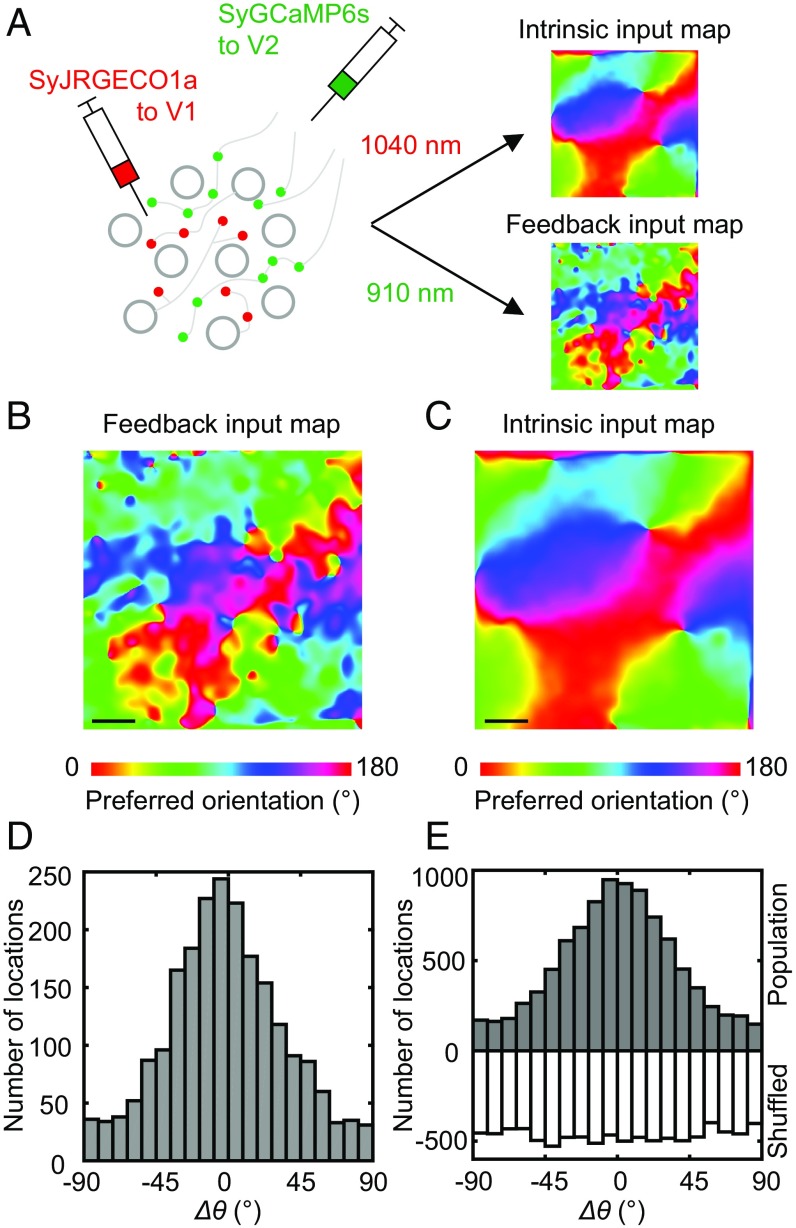

To directly compare the orientation map of V2–V1 feedback projections with the map of V1 intrinsic connections, we labeled the feedback projections with SyGCaMP6s, and the V1 intrinsic connections with SyJRGECO1a (Fig. 6A). We mapped the feedback and intrinsic connections, respectively, at depths of 30 and 110 μm from the cortical surface, where the two sets of axon boutons are concentrated. Dual-color calcium imaging at the same regions showed that large-scale orientation maps from the two projections were broadly similar (Fig. 6 B and C). The differences (Δθ = θfeedback − θintrinsic) between the preferred orientations of two maps were distributed with a peak around zero (Fig. 6 D and E), whereas no such peak was found when the orientation preferences of one map were shuffled (Fig. 6E; two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, P < 10−4), indicating that the orientation maps of these two sets of axon projections were aligned. We note, however, that the alignment precision is lower than that between the orientation maps of V1 intrinsic axon boutons and cell bodies, as indicated by the larger width of the Δθ distribution (two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, P < 10−4). Taken together, these results suggest that V2–V1 feedback axon boutons are also organized into an orientation map that is aligned with the V1 map, although with less precision than the V1 intrinsic axon boutons.

Fig. 6.

Comparison between the functional organization of V2 feedback projections and V1 intrinsic connections. (A) V1 intrinsic inputs were labeled with the red presynaptic indicator SyJRGECO1a and imaged at 1,040 nm, while V2 feedback inputs were labeled with the green presynaptic indicator SyGCaMP6s and imaged at 910 nm. (B and C) Example large-scale orientation maps of the V2–V1 feedback and V1 intrinsic axon boutons in the same imaged V1 region. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (D) Distribution of the difference (Δθ: −1.1° ± 36.4°; mean ± SD) between the preferred orientations of the V2–V1 feedback and V1 intrinsic inputs shown in B and C. (E) Distribution of Δθ for all of the imaged regions (Upper: 1.0° ± 37.6°; mean ± SD) was significantly different from the distribution obtained after random shuffling of one of the maps (Lower). Two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, P < 10−4.

Functional Implications of the Organized Presynaptic Inputs.

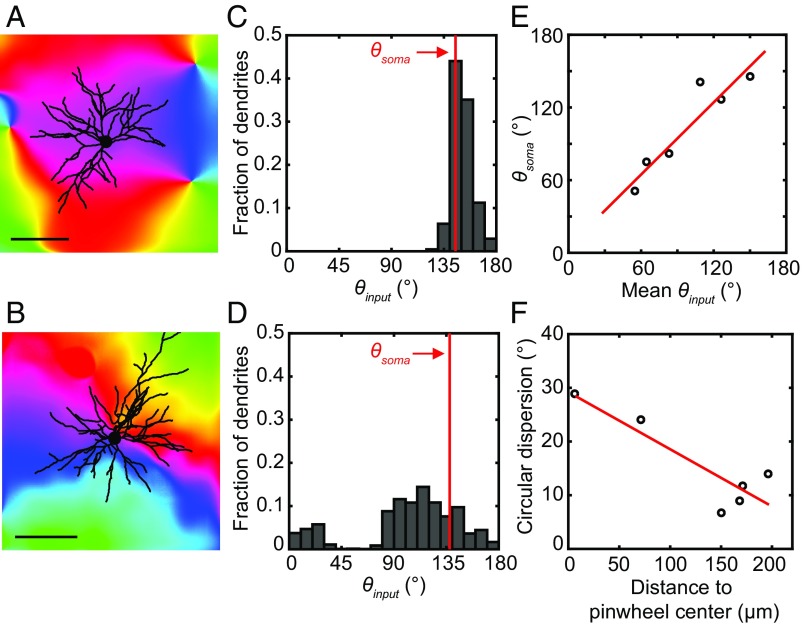

How does the organization of V1 intrinsic and V2–V1 feedback axon boutons into orientation maps influence the orientation tuning of V1 neurons? To address this question, we examined the distribution of entire dendritic trees of single V1 neurons (labeled by mRuby2) relative to the large-scale orientation map of V1 intrinsic inputs (labeled by SyGCaMP6s) imaged at a lower resolution (Fig. 7 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). Under the assumption of nonselective connectivity between dendrites and their surrounding axon boutons, we estimated the orientation preference of input to each 1-μm dendritic segment with the average SyGCaMP6s response surrounding the segment. When the input orientation preferences of all 1-μm dendritic segments of a single V1 neuron were pooled together, we found that the distribution of preferred orientations exhibit a single peak for each of the six neurons examined (Fig. 7 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Circular mean of the distribution agreed closely to the preferred orientation of the cell body according to its location in the orientation map (Fig. 7 C–E; linear regression, R2 = 0.87, P = 0.006, n = 6 neurons), indicating that the orientation preference of integrated V1 intrinsic inputs is matched to neuronal output. The input distribution tended to be broader when the cell body was located closer to pinwheel centers (Fig. 7F; linear regression, R2 = 0.78, P = 0.02, n = 6 neurons), possibly leading to lower orientation selectivity for these neurons (32, 33).

Fig. 7.

Averaged orientation preference of intrinsic inputs received by the dendritic tree is matched to the cell body preference. (A and B) Entire dendritic trees of two V1 neurons were traced and superimposed on the large-scale orientation maps of intrinsic axon boutons mapped from the same regions using SyGCaMP6s. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (C and D) Distribution of the preferred orientations of estimated intrinsic inputs to all 1-μm dendritic segments (θinput) for the neurons in A and B. The red lines indicate the preferred orientations of the cell bodies (θsoma) according to their locations in the orientation map. (E) Strong correlation between θsoma and the average θinput received by the neuron. (F) Circular dispersion of θinput for each neuron negatively correlated with the distance of the cell body to the nearest pinwheel center.

Given that the orientation preferences of the six neurons we studied were matched to that of their estimated intrinsic input, we further tested whether the cell body orientation map could be predicted by the intrinsic input map (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), based on the dual-color calcium imaging dataset where the responses of V1 cell bodies and intrinsic presynaptic inputs were simultaneously recorded (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A–C). Because dendrites could not be traced for such densely labeled neurons, we simulated 20 dendrites (each with a length of 150 μm pointing toward random directions; SI Appendix, Fig. S10D) for each cell body and calculated the preferred orientation of the total intrinsic input from the surrounding axon bouton responses using the same method as in Fig. 7. When each neuron was colored according to the orientation preference of estimated total intrinsic inputs, a pinwheel-like map that agreed closely with the actual cell body map emerged (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 E and F). Therefore, dendritic integration of functionally organized intrinsic inputs under the assumption of random connectivity and uniform synaptic weight is sufficient to reproduce most features of the cell body map, suggesting an important reinforcing role for the organized intrinsic inputs to the orientation map of V1 cell bodies.

Discussion

In this work, we showed that the development of presynaptic GECIs in two colors allows the direct comparison between the functional organization of either two presynaptic inputs to, or the input and output of specific neuronal populations. Using these tools, we showed that axon boutons of V1 intrinsic and V2–V1 feedback projections are both spatially organized into orientation maps aligned with the V1 cell body map. Such arrangements could result in strong postsynaptic clustering of functionally similar inputs and reinforce the orientation maps observed in V1 neurons.

Our results strongly support previous anatomical studies showing a like-to-like connectivity for long-range horizontal connections (5–7) and further shows that such a rule remains accurate to the level of single neurons, in that the preferred orientation of V1 neurons closely track the average preferred orientation of the nearby V1 intrinsic axon boutons (Fig. 4). We note that the use of relatively coarse orientation intervals (45°) in most of our experiments sets a limit on how precise the degree of matching could be measured, although control experiments with a finer interval of 22.5° yielded similar results. Imaging of individual axon boutons showed that, despite global matching, some boutons could deviate significantly from the local average in orientation preference, both in the iso-orientation domains and around the pinwheel centers. Such deviations could be attributed to at least three possible factors. First, inhibitory axons are reported to be less specific in targeting similar orientation domains than excitatory axons (34). The fact that boutons with larger deviations are less orientation-selective is consistent with this possibility, since previous works have shown that inhibitory V1 neurons are less orientation-selective than excitatory neurons (35, 36). Second, axon boutons located close to the originating cell body have been shown to be less specific in targeting than those more distantly located (5). Third, individual pyramidal neurons could also show different degrees of like-to-like targeting (37). Axon boutons that deviate significantly from the local average orientation preference may play a role in neuronal computations that require converging information from multiple orientations.

Our results provide a presynaptic perspective complementary to a recent study of the functional organization of the postsynaptic spines in ferret V1 (29). In that work, spines with similar preferred orientations are frequently found to cluster on the same branches, with a degree of homogeneity (circular dispersion of preferred orientation, ∼20°) similar to that found here for the V1 intrinsic axon boutons surrounding dendritic segments (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). These results suggest that organized presynaptic axon boutons strongly favor postsynaptic functional clustering, and that such clustering could be prevalent in cortical areas with functional maps of presynaptic inputs. Interestingly, recent studies on rodent V1 showed that inputs with similar receptive fields are likely to cluster on neighboring spines (38), while inputs with similar preferred orientations are scattered without obvious functional clustering (9, 39), perhaps because of the presence of presynaptic maps for the former but not the latter. A more detailed comparison between the functional organizations of axon boutons and spines would require the identification of actual synaptic contacts and the simultaneous mapping of presynaptic and postsynaptic activities (10, 24, 25, 40, 41).

The contribution of intracortical inputs to the orientation tuning of V1 neurons and the formation of V1 orientation map has been controversial (42). Our results showed that nonselective dendritic integration of the organized V1 intrinsic inputs is sufficient to yield an orientation map of cell bodies closely similar to that actually measured (Fig. 7 and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). More selective sampling of presynaptic inputs by postsynaptic spines, as has been reported from mouse V1 (43), could further strengthen the orientation tuning of V1 neurons. It is possible that the organized intrinsic inputs, if present relatively early during development, would facilitate the initial formation of the cell body orientation map. Alternatively, cell body maps could be initially established by the feedforward inputs (44), and then strengthened and stabilized by the organized intrinsic inputs (45, 46). Further studies on the temporal sequence of orientation map formation for V1 cell bodies and presynaptic inputs will shed more light on this issue. The V2–V1 feedback projections are less organized according to preferred orientations, suggesting that their contribution to V1 neuron orientation selectivity is secondary to the intrinsic inputs. Instead, these projections may play a more important role in facilitating the detection of more elongated spatial structures beyond the receptive field of single V1 neurons.

The method we used here to label the V1 intrinsic and V2–V1 feedback projections has some important limitations. For example, although we performed multiple virus injections to label the V1 intrinsic connections, such labeling could not cover the entire V1, and those connections originating from the more distant sites may be underrepresented in our samples. Our labeling method also resulted in a mixture of boutons originating from multiple cortical layers and neuronal subtypes that are not completely specified by the experimenter. It is worth noting that axon boutons originating from different layers or neuronal subtypes might exhibit distinct functional organizations, a possibility that could be addressed in further studies. For example, recent development of novel vectors targeting inhibitory neurons should allow the comparison of the functional organization of inhibitory axon boutons with that of excitatory axon boutons (47). Elucidating how these different sources of presynaptic inputs are organized in a coordinated manner and integrated by the postsynaptic dendrites to generate the neuronal response properties would be a critical step toward understanding the computational principles in V1.

Materials and Methods

Experimental procedures for plasmid construction, animal surgery, calcium imaging, and data analysis are described in detail in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Neuroscience, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Fitzpatrick, Zhiming Shen, and Wenzhi Sun for helpful comments; Lin Xu and Yuexiong Yang for providing animals; Huanhuan Zeng for assistance in intrinsic imaging; and Tobias Bonhoeffer, Douglas Kim, Leon Lagnado, Zilong Qiu, and Tobias Rose for plasmids. This work was supported by grants from the Chinese Academy of Sciences [Strategic Priority Research Program, XDB02020001 (to M.-m.P.) and XDB02040100 (to A.G.); Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, QYZDY-SSW-SMCO01 (to M.-m.P.); International Partnership Program, 153D31KYSB20170059 (to M.-m.P.)]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China [30921064, 90820008, and 31130027 (to A.G.)], Shanghai Key Basic Research Project [16JC1420201 (to M.-m.P.)], and Ministry of Science and Technology [973 Program, 2011CBA00400 (to A.G. and M.-m.P.)].

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1719711115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Blasdel GG, Salama G. Voltage-sensitive dyes reveal a modular organization in monkey striate cortex. Nature. 1986;321:579–585. doi: 10.1038/321579a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonhoeffer T, Grinvald A. Iso-orientation domains in cat visual cortex are arranged in pinwheel-like patterns. Nature. 1991;353:429–431. doi: 10.1038/353429a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Shape and arrangement of columns in cat’s striate cortex. J Physiol. 1963;165:559–568. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohki K, et al. Highly ordered arrangement of single neurons in orientation pinwheels. Nature. 2006;442:925–928. doi: 10.1038/nature05019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosking WH, Zhang Y, Schofield B, Fitzpatrick D. Orientation selectivity and the arrangement of horizontal connections in tree shrew striate cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2112–2127. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-02112.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert CD, Wiesel TN. Columnar specificity of intrinsic horizontal and corticocortical connections in cat visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2432–2442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-07-02432.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malach R, Amir Y, Harel M, Grinvald A. Relationship between intrinsic connections and functional architecture revealed by optical imaging and in vivo targeted biocytin injections in primate striate cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10469–10473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shmuel A, et al. Retinotopic axis specificity and selective clustering of feedback projections from V2 to V1 in the owl monkey. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2117–2131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4137-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen TW, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dana H, et al. Sensitive red protein calcium indicators for imaging neural activity. eLife. 2016;5:e12727. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue M, et al. Rational design of a high-affinity, fast, red calcium indicator R-CaMP2. Nat Methods. 2015;12:64–70. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian L, et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, et al. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science. 2011;333:1888–1891. doi: 10.1126/science.1208592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glickfeld LL, Andermann ML, Bonin V, Reid RC. Cortico-cortical projections in mouse visual cortex are functionally target specific. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:219–226. doi: 10.1038/nn.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsui T, Ohki K. Target dependence of orientation and direction selectivity of corticocortical projection neurons in the mouse V1. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:143. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz-Martín A, et al. A dedicated circuit links direction-selective retinal ganglion cells to the primary visual cortex. Nature. 2014;507:358–361. doi: 10.1038/nature12989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondo S, Ohki K. Laminar differences in the orientation selectivity of geniculate afferents in mouse primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:316–319. doi: 10.1038/nn.4215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun W, Tan Z, Mensh BD, Ji N. Thalamus provides layer 4 of primary visual cortex with orientation- and direction-tuned inputs. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:308–315. doi: 10.1038/nn.4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo S, Yoshida T, Ohki K. Mixed functional microarchitectures for orientation selectivity in the mouse primary visual cortex. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13210. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohki K, Chung S, Ch’ng YH, Kara P, Reid RC. Functional imaging with cellular resolution reveals precise micro-architecture in visual cortex. Nature. 2005;433:597–603. doi: 10.1038/nature03274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scholl B, Pattadkal JJ, Rowe A, Priebe NJ. Functional characterization and spatial clustering of visual cortical neurons in the predatory grasshopper mouse Onychomys arenicola. J Neurophysiol. 2017;117:910–918. doi: 10.1152/jn.00779.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzpatrick D. The functional organization of local circuits in visual cortex: Insights from the study of tree shrew striate cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:329–341. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dreosti E, Odermatt B, Dorostkar MM, Lagnado L. A genetically encoded reporter of synaptic activity in vivo. Nat Methods. 2009;6:883–889. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, et al. mGRASP enables mapping mammalian synaptic connectivity with light microscopy. Nat Methods. 2011;9:96–102. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Li Y, Lei Z, Wang K, Guo A. Transformation of odor selectivity from projection neurons to single mushroom body neurons mapped with dual-color calcium imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12084–12089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305857110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, et al. Neural signatures of dynamic stimulus selection in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1104–1113. doi: 10.1038/nn.4581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nauhaus I, Nielsen KJ, Disney AA, Callaway EM. Orthogonal micro-organization of orientation and spatial frequency in primate primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1683–1690. doi: 10.1038/nn.3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee KS, Huang X, Fitzpatrick D. Topology of ON and OFF inputs in visual cortex enables an invariant columnar architecture. Nature. 2016;533:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature17941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson DE, Whitney DE, Scholl B, Fitzpatrick D. Orientation selectivity and the functional clustering of synaptic inputs in primary visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1003–1009. doi: 10.1038/nn.4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosking WH, Kretz R, Pucak ML, Fitzpatrick D. Functional specificity of callosal connections in tree shrew striate cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2346–2359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02346.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockland KS, Pandya DN. Laminar origins and terminations of cortical connections of the occipital lobe in the rhesus monkey. Brain Res. 1979;179:3–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nauhaus I, Benucci A, Carandini M, Ringach DL. Neuronal selectivity and local map structure in visual cortex. Neuron. 2008;57:673–679. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schummers J, Mariño J, Sur M. Synaptic integration by V1 neurons depends on location within the orientation map. Neuron. 2002;36:969–978. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kisvárday ZF, Eysel UT. Functional and structural topography of horizontal inhibitory connections in cat visual cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:1558–1572. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerlin AM, Andermann ML, Berezovskii VK, Reid RC. Broadly tuned response properties of diverse inhibitory neuron subtypes in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2010;67:858–871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson DE, et al. GABAergic neurons in ferret visual cortex participate in functionally specific networks. Neuron. 2017;93:1058–1065 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin KA, Roth S, Rusch ES. Superficial layer pyramidal cells communicate heterogeneously between multiple functional domains of cat primary visual cortex. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5252. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iacaruso MF, Gasler IT, Hofer SB. Synaptic organization of visual space in primary visual cortex. Nature. 2017;547:449–452. doi: 10.1038/nature23019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jia H, Rochefort NL, Chen X, Konnerth A. Dendritic organization of sensory input to cortical neurons in vivo. Nature. 2010;464:1307–1312. doi: 10.1038/nature08947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Guo A, Li H. CRASP: CFP reconstitution across synaptic partners. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;469:352–356. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macpherson LJ, et al. Dynamic labelling of neural connections in multiple colours by trans-synaptic fluorescence complementation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10024. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferster D, Miller KD. Neural mechanisms of orientation selectivity in the visual cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:441–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee WC, et al. Anatomy and function of an excitatory network in the visual cortex. Nature. 2016;532:370–374. doi: 10.1038/nature17192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko H, et al. The emergence of functional microcircuits in visual cortex. Nature. 2013;496:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li YT, Ibrahim LA, Liu BH, Zhang LI, Tao HW. Linear transformation of thalamocortical input by intracortical excitation. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1324–1330. doi: 10.1038/nn.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lien AD, Scanziani M. Tuned thalamic excitation is amplified by visual cortical circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/nn.3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dimidschstein J, et al. A viral strategy for targeting and manipulating interneurons across vertebrate species. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1743–1749. doi: 10.1038/nn.4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berens P. CircStat: A Matlab toolbox for circular statistics. J Stat Softw. 2009;31:1–21. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.