Significance

Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) regulates phosphate and vitamin D metabolism and induces left heart hypertrophy. The importance of FGF23 is supported by the consequences of FGF23 deficiency: FGF23-deficient mice have a significantly reduced life span and recapitulate human age-associated diseases. Moreover, FGF23 has gained attention as a potential disease biomarker due to its positive correlation with disease activity, progression, and outcome in chronic kidney disease or cardiovascular disorders. It is, however, not entirely clear whether FGF23 merely indicates disease or actively contributes to disease progression. Therefore, it is important to explore the regulation of FGF23 production, which is similarly incompletely understood. Our paper identifies fundamental insulin/IGF1-dependent PI3K/Akt/FOXO1 signaling as a key suppressor of FGF23 formation.

Keywords: PI3K, PKB/Akt, Klotho, phosphate

Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) is produced by bone cells and regulates renal phosphate and vitamin D metabolism, as well as causing left ventricular hypertrophy. FGF23 deficiency results in rapid aging, whereas high plasma FGF23 levels are found in several disorders, including kidney or cardiovascular diseases. Regulators of FGF23 production include parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcitriol, dietary phosphate, and inflammation. We report that insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) are negative regulators of FGF23 production. In UMR106 osteoblast-like cells, insulin and IGF1 down-regulated FGF23 production by inhibiting the transcription factor forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) through phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt signaling. Insulin deficiency caused a surge in the serum FGF23 concentration in mice, which was reversed by administration of insulin. In women, a highly significant negative correlation between FGF23 plasma concentration and increase in plasma insulin level following an oral glucose load was found. Our results provide strong evidence that insulin/IGF1-dependent PI3K/PKB/Akt/FOXO1 signaling is a powerful suppressor of FGF23 production in vitro as well as in mice and in humans.

The proteohormone fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) is synthesized by bone cells (1) and regulates phosphate and vitamin D metabolism (2). In the kidney, FGF23 inhibits phosphate reabsorption by stimulating the internalization of the phosphate transporter NaPiIIa and suppresses the formation of calcitriol or 1,25(OH)2D3, the active form of vitamin D, by inhibiting 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1-α-hydroxylase (encoded by the Cyp27b1 gene) (1). In the parathyroid gland, FGF23 suppresses the formation of parathyroid hormone (PTH) (3). All these endocrine effects of FGF23 are mediated by a membrane receptor that is made up of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 c-splicing form (FGFR1c) and membrane-anchored Klotho (1, 4). Apart from membrane Klotho, a soluble form exists (sKlotho) that itself exerts several endocrine effects. SKlotho can be found in blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid (5, 6). Interestingly, FGF23 further triggers hypertrophy of the left cardiac ventricle (7) through a cardiac receptor not depending on Klotho (8).

Klotho-null mice have a short life span with clear signs of neuronal, metabolic, muscle, skin, or cardiovascular aging that resembles human aging (9). In large part, the aging is due to dysregulated phosphate metabolism, which results in massive calcification in most tissues and organs (9). FGF23-deficient mice exhibit similar symptoms due to the joint action of Klotho and FGF23 in phosphate metabolism (2).

The plasma FGF23 concentration is elevated in several acute and chronic diseases, which makes FGF23 a candidate as a meaningful disease biomarker (10). The role of FGF23 is characterized best in chronic kidney disease (CKD), where a high FGF23 plasma concentration occurs very early even before the onset of appreciable hyperparathyroidism and hyperphosphatemia, which are typical sequelae of CKD (11). In CKD and coronary heart disease, FGF23 is a powerful predictor of mortality (12).

Known regulators of FGF23 production include PTH (13), 1,25(OH)2D3 (14), iron status (15), dietary phosphate (16), and inflammation (15, 17). Polycystic kidneys are also a source of enhanced FGF23 production (18).

Insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) exert their pleiotropic effects through phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt signaling (19). Stimulation of insulin or IGF1 receptors leads to the activation of PI3K, which ultimately results in enhanced activity of PKB/Akt, a key mediator of insulin and IGF1 effects in the regulation of cell proliferation, survival, and metabolism (19). Downstream targets of PKB/Akt include glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) (19) and transcription factor forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) (20–22), which are both inhibited via phosphorylation. Transgenic mice expressing PI3K/PKB/Akt-resistant GSK3 (23) suffer from renal phosphate loss (phosphaturia) (24) and have an elevated serum concentration of FGF23 (25). Moreover, PKBβ/Akt2 and serum and glucocorticoid kinase 3 (SGK3), another downstream signaling element of PI3K, regulate the renal phosphate transporter NaPiIIa. Hence, both PKBβ/Akt2- and SGK3-deficient mice suffer from phosphaturia (26, 27).

The impact of insulin deficiency (type 1 diabetes) and resistance (type 2 diabetes) on FGF23 is complex (28). In most studies, diabetes was associated with higher serum levels of FGF23 (29–31), whereas other studies did not find an association (32, 33). Clearly, inflammation is a major trigger of FGF23 production (15), and most patients with type 2 diabetes, especially those with obesity, suffer from inflammatory conditions (34). Type 1 diabetes is similarly associated with inflammation, particularly at later disease stages (35). Therefore, the positive association of diabetes with FGF23 may be due, in large part, to inflammation. The role of insulin and PI3K/PKB/Akt signaling in the regulation of FGF23 production remained, however, hitherto elusive.

Here, we explored the significance of insulin and insulin-dependent signaling for the synthesis of FGF23.

Results

Insulin and IGF1 Down-Regulate Fgf23 Gene Expression by Activating PI3K/PKB/Akt Signaling.

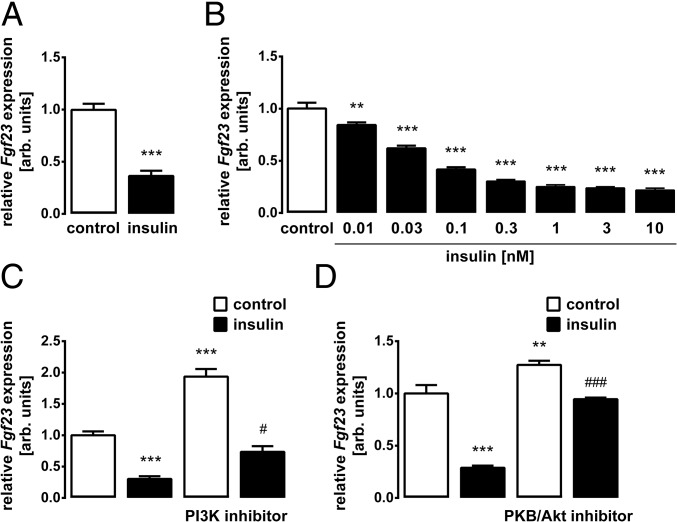

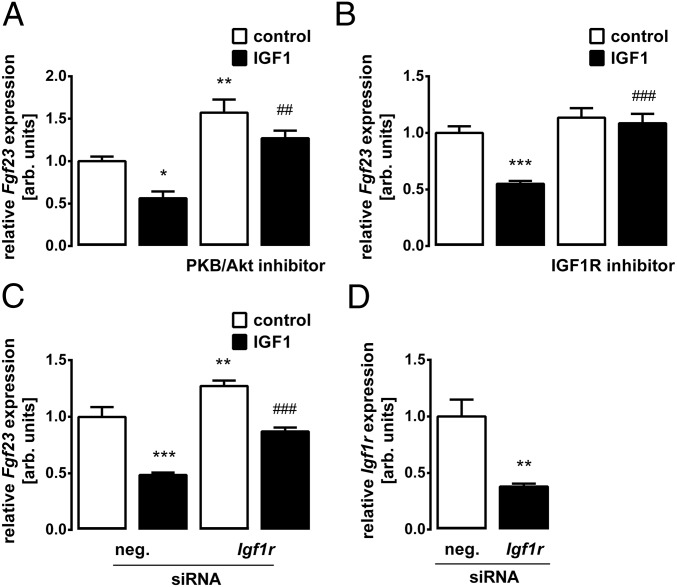

We treated UMR106 osteoblast-like cells with insulin and determined Fgf23 transcripts by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). As demonstrated in Fig. 1A, insulin significantly lowered the abundance of Fgf23 mRNA. The insulin effect was concentration-dependent (Fig. 1B). Since cellular effects of insulin are typically mediated by PI3K, we tested next whether PI3K is involved. Inhibition of PI3K with wortmannin up-regulated Fgf23 gene expression (Fig. 1C). The coadministration of insulin overcame this effect to a large extent (Fig. 1C). The main downstream target of insulin-induced PI3K is PKB/Akt. Similar to wortmannin, PKB/Akt inhibition with MK-2206 increased Fgf23 gene expression and also abrogated the inhibitory effect of insulin on Fgf23 (Fig. 1D). IGF1 is another important inducer of PI3K/Akt signaling. As demonstrated in Fig. 2A, IGF1 indeed mimicked the insulin effect on Fgf23 transcripts. Also, the IGF1 effect was significantly attenuated in the presence of MK-2206 (Fig. 2A). IGF1 was effective through the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) as IGF1R antagonist BMS-754807 (Fig. 2B) and siRNA-mediated knockdown of the Igf1r gene (Fig. 2 C and D) significantly attenuated IGF1-induced inhibition of Fgf23 gene expression.

Fig. 1.

Insulin down-regulates Fgf23 expression through PI3K/PKB/Akt signaling. Bar diagrams represent the mRNA abundance of Fgf23 measured by qRT-PCR in UMR106 cells incubated without or with insulin (10 nM; A, C, and D) or at the indicated insulin concentration (B) in the absence and presence of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (5 μM, C) or PKB/Akt inhibitor MK-2206 (1 μM, D). Gene expression was normalized to Tbp as a housekeeping gene, and the values are expressed as arithmetic means ± SEM (n = 5–8). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from vehicle (first bar). #P < 0.05 and ###P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from an absence of wortmannin or MK-2206 (second bar vs. fourth bar). arb., arbitrary.

Fig. 2.

IGF1 is a negative regulator of Fgf23 transcription. Fgf23 transcript levels in UMR106 cells incubated without or with IGF1 (0.5 μg/mL; A–C) in the absence and presence of the PKB/Akt inhibitor MK-2206 (1 μM, A), the IGF1R inhibitor BMS-754807 (1 μM, B), or treatment with Igf1r-specific siRNA and nonsense siRNA as a negative control (neg. siRNA, C) are shown. (D) Igf1r mRNA expression in UMR106 cells treated with nonsense siRNA or Igfr1 siRNA. Gene expression was normalized to Tbp as a housekeeping gene, and the values are expressed as arithmetic means ± SEM (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from vehicle (first bar). ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from an absence of MK-2206, BMS-754807, or Igf1r-specific siRNA (second bar vs. fourth bar). arb., arbitrary.

The Insulin Effect on Fgf23 Is Mediated by the PKB/Akt-Regulated Transcription Factor FOXO1.

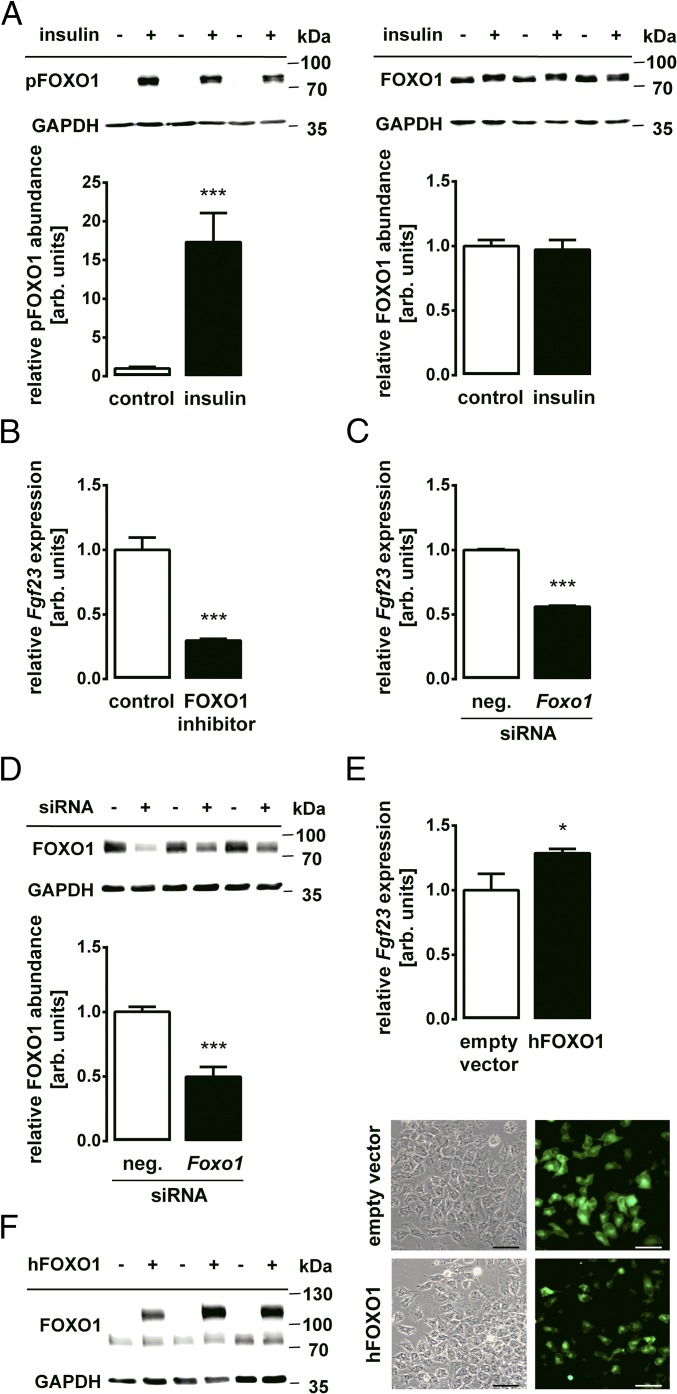

Many metabolic effects of insulin-dependent PKB/Akt signaling are mediated by the inhibitory phosphorylation of FOXO1 (21). As illustrated by Western blotting in Fig. 3A, treatment of the cells with insulin induced the phosphorylation of FOXO1 at Ser256, a site phosphorylated by PKB/Akt (36), pointing to an inhibition of the transcriptional activity of FOXO1. Next, we studied whether transcriptional activity of FOXO1 is required for Fgf23 gene transcription. Similar to treatment with insulin, the incubation of UMR106 cells with the FOXO1 inhibitor AS1842856 resulted in down-regulation of Fgf23 gene expression (Fig. 3B). The knockdown of Foxo1 gene expression using specific siRNA also lowered the abundance of Fgf23 transcripts (Fig. 3C). The siRNA-mediated down-regulation of FOXO1 was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 3D). Conversely, the overexpression of FOXO1 up-regulated Fgf23 gene expression (Fig. 3E). Efficient transfection with the respective plasmid encoding FOXO1, along with GFP, was confirmed by Western blotting as well as by fluorescence (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Transcription factor FOXO1 regulates Fgf23 expression. (A, Upper) Original Western blots of phospho-FOXO1 (pFOXO1) and GAPDH (Left) or FOXO1 and GAPDH (Right) abundance in UMR106 cells incubated with or without 10 nM insulin for 30 min. (A, Lower) Densitometric analysis (arithmetic means ± SEM, n = 7) of phospho-FOXO1 or FOXO1 protein abundance normalized to GAPDH. (B) Arithmetic means ± SEM (n = 5) of Fgf23 mRNA abundance in UMR106 cells incubated with or without the FOXO1 inhibitor AS1842856 (50 nM). (C) Arithmetic means ± SEM (n = 5) of Fgf23 mRNA abundance in UMR106 cells treated with Foxo1-specific or nonsense siRNA as a negative control (neg. siRNA). (D) Representative Western blot and densitometric analysis (arithmetic means ± SEM, n = 7) of FOXO1 protein abundance normalized to GAPDH in Foxo1-specific or nonsense siRNA-treated (neg. siRNA) cells. (E) Arithmetic means ± SEM (n = 7) of Fgf23 mRNA in UMR106 cells transfected with a vector construct encoding human FOXO1-WT or with an empty vector pEGFP-C1 as a control. (F) Representative original Western blot (Left) demonstrating FOXO1 and the GFP-FOXO1 fusion protein abundance and representative microscopy image (Right) showing the GFP signal of the fusion protein or GFP alone in UMR106 cells following transfection with human FOXO1-WT or with an empty vector pEGFP-C1. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from control-treated cells. arb., arbitrary.

In Mice, Insulin Deficiency Elevates the FGF23 Serum Level, Which Is Again Normalized by Insulin Administration.

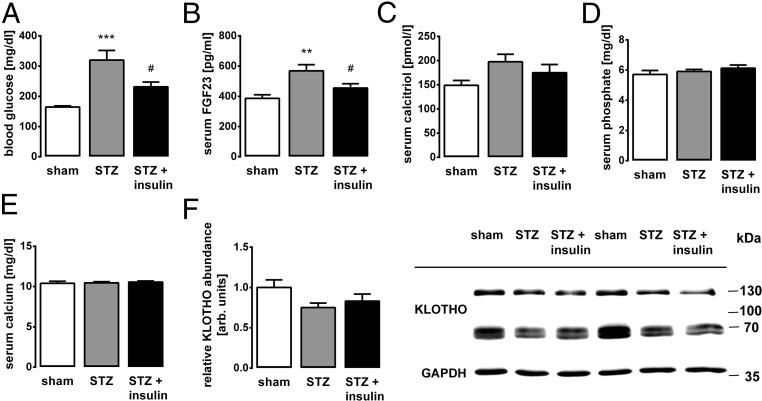

Our in vitro studies suggest that insulin is a potent negative regulator of FGF23 production through PI3K/PKB/Akt/FOXO1 signaling. Next, we carried out in vivo experiments to assess the physiological relevance of insulin-dependent suppression of FGF23 production. To this end, we depleted wild-type mice of endogenous insulin production by means of streptozotocin (STZ), a substance with toxicity to insulin-producing β cells, thereby inducing acute insulin deficiency. As expected, we observed a surge in the blood glucose level upon treatment with STZ, which was prevented by daily insulin injections over a period of 10 d in another group of mice (Fig. 4A). Importantly, insulin deficiency in STZ-treated animals resulted in an increase in the serum FGF23 concentration that was significantly and almost completely prevented in STZ-treated mice injected daily with insulin (Fig. 4B). Hence, the inhibitory effect of insulin on FGF23 production is of high physiological relevance in vivo. Serum calcitriol (Fig. 4C), phosphate (Fig. 4D), calcium (Fig. 4E), and renal Klotho expression (Fig. 4F) were not affected by the treatment.

Fig. 4.

Insulin deficiency results in a surge of the serum FGF23 level that is reversed by insulin. Arithmetic means ± SEM (n = 12 mice per group) of the blood glucose (A), serum C-terminal FGF23 (B), calcitriol (C), phosphate (D), and calcium (E) concentrations, as well as densitometric analysis of renal Klotho protein expression normalized to GAPDH (F, Left) and a representative Western blot (F, Right) in sham-treated (first bars) or STZ-treated mice receiving daily saline (second bars) or insulin (third bars) injections. arb., arbitrary. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from sham-treated mice, and #P < 0.05 indicates significant difference between mice treated with STZ only and mice treated with STZ and insulin.

Plasma Insulin Is Negatively Correlated with the Plasma FGF23 Concentration in Humans.

We finally investigated whether insulin-dependent suppression of FGF23 is also relevant in humans. In healthy volunteers, we analyzed baseline hormones as well as changes of hormones after an oral glucose load.

The baseline insulin concentration in the fasted subjects was inversely correlated with baseline FGF23 (r = −0.282, P = 0.005) as well as with homeostatic model assessment-estimated insulin resistance (HOMA-IR; r = −0.293, P = 0.003), a clinical index for insulin resistance, but not with proinsulin and HOMA-β, a parameter describing pancreatic β cell function and indicating insulin secretion (Table 1). These results are in line with an inhibitory effect of insulin on FGF23 secretion. The lack of correlation of baseline proinsulin and HOMA-β with baseline FGF23 suggests that a putative inhibitory effect of FGF23 on insulin secretion is a very unlikely explanation of our findings.

Table 1.

Correlation of baseline FGF23, insulin, proinsulin, HOMA-IR index, and HOMA-β index in fasted healthy pregnant women

| FGF23 | Insulin | Proinsulin | HOMA-IR | HOMA-β | ||||||

| Parameter | rs | P | rs | P | rs | P | rs | P | rs | P |

| FGF23 | 1.000 | — | −0.282** | 0.005 | 0.035 | 0.735 | −0.293** | 0.003 | −0.148 | 0.146 |

| Insulin | −0.282** | 0.005 | 1.000 | — | 0.324** | 0.001 | 0.992** | 0.000 | 0.799** | 0.000 |

| Proinsulin | 0.035 | 0.735 | 0.324** | 0.001 | 1.000 | — | 0.339** | 0.001 | 0.208* | 0.040 |

| HOMA-IR | −0.293** | 0.003 | 0.992** | 0.000 | 0.339** | 0.001 | 1.000 | — | 0.730** | 0.000 |

| HOMA-β | −0.148 | 0.146 | 0.799** | 0.000 | 0.208* | 0.040 | 0.730** | 0.000 | 1.000 | — |

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient [Spearman’s rho (rs)] was determined for each group (n = 98). Correlation is significant at the *P < 0.05 level and **P < 0.01 level.

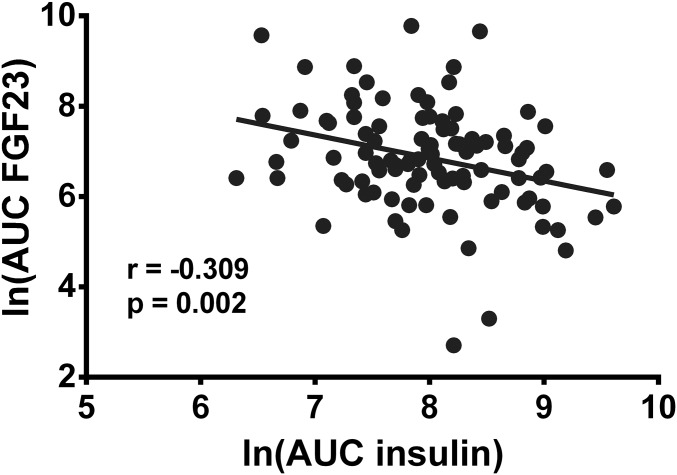

Baseline insulin increased from 12.2 ± 8.5 μU/mL to 113.1 ± 87.0 μU/mL 60 min after the oral glucose load of 75 g. The area under the curve (AUC) of the insulin time curve reflects insulin secretion 60 min after the glucose challenge, and the AUC of the FGF23 reflects the amount of secreted FGF23 within 60 min in response to the insulin challenge. We observed an inverse correlation (r = −0.287, P = 0.004) (Fig. 5 and Table 2), suggesting that insulin is a negative regulator of FGF23. In a further model, we correlated the AUC of insulin during the first 60 min after an oral glucose challenge with the AUC of FGF23 from 60 to 120 min after the glucose load. This model serves to test long-lasting effects of the insulin secretion in the first 60 min after glucose load. Again, we observed an inverse correlation (r = −0.266, P = 0.008) (Table 2). These results suggest that enhanced insulin secretion due to the oral glucose load suppressed FGF23 production in healthy volunteers with intact insulin signaling. We furthermore tested the correlation of insulin secretion (AUC of insulin during the first 60 min after glucose load) with the FGF23 concentrations at the time points of 60 min and 120 min. Again, an inverse relationship (Table 2) could be detected. Taken together, the analysis of baseline hormone concentrations (Table 1) and changes of hormones after the oral glucose load (Fig. 5 and Table 2) indicate that insulin is a potent negative regulator of FGF23 in humans as well.

Fig. 5.

Insulin and FGF23 secretion are negatively correlated in humans. A scatter plot representing the correlation of the AUC of the insulin time curve reflecting insulin secretion during the first 60 min after an oral glucose tolerance test in healthy volunteers and the AUC of the FGF23 time curve during the same time period reflecting the secreted FGF23 within 60 min is shown. Due to the right squid distribution of the raw data, a natural log transformation was performed. The Pearson correlation coefficient was determined (n = 98). ln, natural logarithm.

Table 2.

Correlation of insulin and FGF23 changes after an oral glucose test in fasted healthy pregnant women

| AUC insulin (0–60 min) | AUC FGF23 (0–60 min) | AUC FGF23 (60–120 min) | FGF23 (60 min) | FGF23 (120 min) | ||||||

| Parameter | rs | P | rs | P | rs | P | rs | P | rs | P |

| AUC insulin (0–60 min) | 1.000 | — | −0.287** | 0.004 | −0.266** | 0.008 | −0.200* | 0.049 | −0.275** | 0.006 |

| AUC FGF23 (0–60 min) | −0.287** | 0.004 | 1.000 | — | 0.885** | 0.000 | 0.917** | 0.000 | 0.677** | 0.000 |

| AUC FGF23 (60–120 min) | −0.266** | 0.008 | 0.885** | 0.000 | 1.000 | — | 0.921** | 0.000 | 0.868** | 0.000 |

| FGF23 (60 min) | −0.200* | 0.049 | 0.917** | 0.000 | 0.921** | 0.000 | 1.000 | — | 0.669** | 0.000 |

| FGF23 (120 min) | −0.275** | 0.006 | 0.677** | 0.000 | 0.868** | 0.000 | 0.669** | 0.000 | 1.000 | — |

AUC represents the time curve of hormone release after glucose challenge between respective time points. In addition, a correlation with the FGF23 concentration at the appropriate times was performed. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient [Spearman’s rho (rs)] was determined for each group (n = 98). Correlation is significant at the *P < 0.05 level and **P < 0.01 level.

Discussion

This study provides compelling evidence that insulin is a powerful and physiologically highly relevant suppressor of FGF23 synthesis in vitro as well as in mice and humans. According to our results, the insulin-induced inhibition of the transcription factor FOXO1 through PI3K/PKB/Akt signaling results in the down-regulation of Fgf23 gene transcription.

Given the high prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, which are diseases associated with insulin deficiency or resistance, it may come as surprise that a direct insulin effect on FGF23 has not been described yet. In fact, several studies have addressed the impact of diabetes on plasma FGF23 and have found some associations (29–31), whereas others have not (32, 33). A plausible reason may be the fact that hyperinsulinemia, a state typical of many patients with type 2 diabetes, would be expected to be associated with low FGF23 levels according to our study. On the other hand, hyperinsulinemia and type 2 diabetes are clearly linked to inflammation (34) and kidney disease. Both conditions, alone or in combination, are associated with increased FGF23 production (15, 37). Hence, these effects may compensate for one other, resulting in the observed rather weak associations of diabetes with FGF23. In addition, confounding cofactors, such as inflammation, preexisting CKD, or preexisting coronary heart diseases, may have a further impact on FGF23 secretion in diabetes.

In contrast to the above-mentioned clinical studies analyzing patients with complex metabolic and/or cardiorenal diseases, and thus having many confounding factors with unpredictable effects on FGF23 secretion, our study of healthy pregnant women without renal impairment, manifest insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia (i.e., without known confounding factors) revealed a clear negative correlation of plasma insulin with FGF23. In patients with manifest type 2 diabetes, acute hyperinsulinemia was even reported to enhance FGF23 levels (38), suggesting that intact insulin signaling is required for the suppression of FGF23 secretion by insulin, a notion corroborated by the fact that insulin-resistant individuals have higher FGF23 serum levels (30).

The direct action of insulin on FGF23 was confirmed in mice. The abrogation of insulin secretion in STZ-treated mice resulted in the expected increase in serum FGF23 concentration in comparison to sham-treated animals. STZ-exposed mice additionally treated with daily insulin injections had normal FGF23 levels, suggesting that the STZ effect on insulin secretion, and not a possible side effect, was causative for the observed suppression of FGF23 serum levels. Similar effects were recently observed in STZ-exposed mice treated with insulin for a longer period (39). Insulin lowers the plasma phosphate concentration by inducing cellular phosphate uptake (40), an effect that may further down-regulate FGF23 secretion. However, neither STZ nor insulin treatment significantly changed the serum phosphate concentration or calcitriol, calcium, and renal Klotho expression. Suppression of FGF23 may be a physiological mechanism to prevent excessive hypophosphatemia due to cellular phosphate accumulation induced by insulin.

Our study also addressed the mechanism underlying insulin-induced inhibition of FGF23 formation. Inhibition of PI3K or PKB/Akt revealed the involvement of this signaling pathway. The high medical relevance of PI3K/PKB/Akt is based on the fact that in addition to insulin, many other growth factors are activators. Hence, PI3K/PKB/Akt signaling is utilized by many types of cancer to proliferate, survive, and migrate (41). In line with the relevance of the PI3K/PKB/Akt pathway for growth factor signaling, we found that IGF1 also attenuates FGF23 production involving IGF1R and PI3K/PKB/Akt signaling. Our study therefore suggests that all changes in PI3K/PKB/Akt activity, including possible future pharmacological interventions to combat cancer (41), may have an impact on FGF23.

We identified the transcription factor FOXO1 as the downstream mediator of the PKB/Akt effect on FGF23. Insulin action results in FOXO1 phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting this transcription factor. Pharmacological inhibition of FOXO1, as well as siRNA-mediated silencing, down-regulated Fgf23 gene expression, whereas FOXO1 overexpression, which results in higher cellular levels of nonphosphorylated active FOXO1 (42), led to an enhancement of Fgf23 expression. In general, FOXO1 is known to induce stress resistance in mammalian cells and has even been shown to contribute to longevity in worms and flies (43). In view of these antistress effects of FOXO1, it is interesting to speculate whether and how the FOXO1-dependent up-regulation of FGF23 fits into this concept: On the one hand, FGF23 deficiency is clearly associated with a short life span and age-associated diseases (2), but on the other hand, the up-regulation of FGF23 expression has not been associated with beneficial effects yet and is observed in many diseases (10).

Growth hormone (GH) exerts its growth-promoting effects in bone through IGF1. Bone growth requires a positive phosphate balance, and IGF1 indeed elevates serum phosphate concentration by stimulating renal phosphate reabsorption and calcitriol formation (44), which are effects expected to enhance FGF23 production. In line with this, a positive association of IGF1 with FGF23 was observed (45), and an elevation of FGF23 was found in patients with acromegaly (46) and in GH-deficient children treated with recombinant GH (47, 48). Therefore, IGF1 may have opposing effects on FGF23: A direct FGF23-lowering effect was demonstrated in our study, limiting the indirect FGF23-stimulating actions of IGF1, which may otherwise counteract its phosphate-retaining effect.

Taken together, we demonstrate that insulin- and IGF1-dependent PI3K/PKB/Akt/FOXO1 signaling is a powerful negative regulator of FGF23 production in vitro, in mice, and in humans.

Materials and Methods

The human study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty of Humboldt University, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. The animal study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jinan University.

Glucose Tolerance Test in Healthy Pregnant Women.

This study was performed in a subset of the Berlin Birth Cohort study (details are provided in refs. 49–51). Informed consent was obtained from the human subjects involved. Healthy women in the first trimester of pregnancy were fasted for at least 8 h, followed by an oral glucose load of 75 g and further blood collections after 60 and 120 min, respectively. Glucose, insulin, and proinsulin were measured by standard tests, and plasma FGF23 was measured using the Human FGF23 (Intact) ELISA Kit (Immutopics). The HOMA-IR index and HOMA-β index were calculated as described previously (52).

Animals and Experimental Design.

Male DBA/2N mice (Charles River Laboratories) were subjected to five daily i.p. injections of 40 mg/kg of STZ (Sigma) or vehicle (sham). STZ-treated mice were then divided in two groups, with or without insulin treatment (n = 12 mice per group). The latter group received eight daily injections of 1 U/kg of Insulin Abasaglar (Eli Lilly) at 3:00 PM. From day 9 onward, mice received insulin injections every 12 h. On day 10, blood glucose was measured by a glucometer (Accu-Chek Aviva) 6 h after the last insulin injection. In anesthetized mice, retroorbital blood collection was performed. The following serum parameters were determined: C-terminal FGF23 and calcitriol with ELISA kits (Immutopics and IDS), inorganic phosphate by a photometric method using a Fluitest PHOS kit (Roche), and total calcium using a Fuji DRI CHEM NX500-Analyzer (Fujifilm).

Cell Culture.

UMR106 rat osteosarcoma cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured as described elsewhere (53) and pretreated with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 (Tocris Bioscience) for 24 h since they do not have appreciable amounts of Fgf23 mRNA per se (53, 54). Cells were incubated with 0.01–10 nM insulin or 0.5 μg/mL IGF1 (Sigma) in the absence or presence of 5 μM PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (Sigma), 1 μM PKB/Akt inhibitor MK-2206 (Selleckchem), 1 μM IGF1R inhibitor BMS-754807 (Sigma), or 50 nM FOXO1 inhibitor AS1842856 (Calbiochem) for a further 24 h.

Cell Transfection.

Cells cultured in antibiotic-free complete medium for 24 h were treated with 25 nM siRNA: Foxo1 (L-088495-02), Igf1r (L-091936-02), or nonsense (D-001810-10), and with 5 μL of DharmaFECT1 transfection reagent (T-2001) from Dharmacon for a further 48 h, with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 being present in the last 24 h. For FOXO1 overexpression, cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding EGFP-tagged human WT-FOXO1. The plasmid was generated by subcloning a fragment of FOXO1 expression plasmid 1306 pSG5L HA FKHR wt (kindly provided by W. Sellers, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, through Addgene no. 10693) into the SalI/SmaI site of pEGFP-C1 (Clontech). UMR106 cells cultured for 24 h without antibiotics were transfected with pEGFPC1-hFOXO1 or with the empty vector pEGFP-C1 as a negative control (6 μg of DNA) using FuGENE Transfection Reagent (Promega). Cells were incubated for 24 h without and for a further 24 h with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3.

qRT-PCR.

RNA was extracted using peqGOLD TriFast reagent (VWR), transcribed using a GoScript Reverse Transcription System (Promega), and subjected to PCR with GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega) (95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s) using the following primers: Tbp (ACTCCTGCCACACCAGCC, GGTCAAGTTTACAGCCAAGATTCA), Fgf23 (TGGCCATGTAGACGGAACAC, GGCCCCTATTATCACTACGGAG), Foxo1 (GGTGAAGAGTGTGCCCTACT, ATTTCCCACTCTTGCCTCCC), and Igf1r (TGCTCCAAAGACAAAATACC, CAAAGACTTTACGGTACTCAG). After normalization to Tbp expression, relative quantification of gene expression based on the double-delta Ct (threshold cycle) analysis was carried out.

Western Blotting.

To study FOXO1 phosphorylation, cells were cultured for 24 h in complete medium, followed by another 24 h in serum-free medium. Then, cells were treated with insulin for 30 min. Fifty micrograms of cell lysate or 30 μg of kidney lysate was subjected to a standard Western blot procedure using the following antibodies: anti-FOXO1 (C29H4, 2880), anti–phospho-FOXO1 (Ser256, 9461), and anti-GAPDH (D16H11, 5174S) (all from Cell Signaling Technology), as well as anti-KLOTHO (AF1819; R&D Systems). Secondary anti-rabbit IgG antibody (7074; Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-goat IgG antibody (HAF109; R&D Systems) conjugated with HRP were used. Visualization using ECL detection reagent (GE Healthcare) and densitometrical analysis were performed with a gel documentation system (Syngene G:BOX Chemi XX6; VWR) relative to GAPDH bands.

Statistics.

Arithmetic means ± SEM were calculated, and n represents the number of independent experiments. Comparisons of two groups were made by an unpaired Student’s t test, and for more than two groups, comparisons were calculated via one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s or Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests, using GraphPad Prism. Data of the human study were analyzed with SPSS. Spearman’s rank and Pearson correlations and a correlation matrix for FGF23 and other relevant variables were generated as described previously elsewhere (55). Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Ross, F. Reipsch, and C. Buse for technical help. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grants Fo 695/2-1 and La 315/15-1).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Kuro-O M, Moe OW. FGF23-αKlotho as a paradigm for a kidney-bone network. Bone. 2017;100:4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimada T, et al. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:561–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI19081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krajisnik T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 regulates parathyroid hormone and 1alpha-hydroxylase expression in cultured bovine parathyroid cells. J Endocrinol. 2007;195:125–131. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komaba H, et al. Klotho expression in osteocytes regulates bone metabolism and controls bone formation. Kidney Int. 2017;92:599–611. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuro-o M. Klotho, phosphate and FGF-23 in ageing and disturbed mineral metabolism. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:650–660. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalton G, et al. Soluble klotho binds monosialoganglioside to regulate membrane microdomains and growth factor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:752–757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620301114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faul C, et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4393–4408. doi: 10.1172/JCI46122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faul C. Cardiac actions of fibroblast growth factor 23. Bone. 2017;100:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuro-o M, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnedl C, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Pietschmann P, Amrein K. FGF23 in acute and chronic illness. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:358086. doi: 10.1155/2015/358086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graciolli FG, et al. The complexity of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder across stages of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1436–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isakova T, et al. Longitudinal FGF23 trajectories and mortality in patients with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:579–590. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017070772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavi-Moshayoff V, Wasserman G, Meir T, Silver J, Naveh-Many T. PTH increases FGF23 gene expression and mediates the high-FGF23 levels of experimental kidney failure: A bone parathyroid feedback loop. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F882–F889. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00360.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masuyama R, et al. Vitamin D receptor in chondrocytes promotes osteoclastogenesis and regulates FGF23 production in osteoblasts. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3150–3159. doi: 10.1172/JCI29463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.David V, et al. Inflammation and functional iron deficiency regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 production. Kidney Int. 2016;89:135–146. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrari SL, Bonjour J-P, Rizzoli R. Fibroblast growth factor-23 relationship to dietary phosphate and renal phosphate handling in healthy young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1519–1524. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang B, et al. NFκB-sensitive Orai1 expression in the regulation of FGF23 release. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016;94:557–566. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spichtig D, et al. Renal expression of FGF23 and peripheral resistance to elevated FGF23 in rodent models of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2014;85:1340–1350. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manning BD, Toker A. AKT/PKB signaling: Navigating the network. Cell. 2017;169:381–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eijkelenboom A, Burgering BMT. FOXOs: Signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:83–97. doi: 10.1038/nrm3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue T, et al. The transcription factor Foxo1 controls germinal center B cell proliferation in response to T cell help. J Exp Med. 2017;214:1181–1198. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delpoux A, Lai C-Y, Hedrick SM, Doedens AL. FOXO1 opposition of CD8+ T cell effector programming confers early memory properties and phenotypic diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E8865–E8874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618916114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen H, et al. PI3K-resistant GSK3 controls adiponectin formation and protects from metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:5754–5759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601355113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Föller M, et al. PKB/SGK-resistant GSK3 enhances phosphaturia and calciuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:873–880. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010070757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fajol A, et al. Enhanced FGF23 production in mice expressing PI3K-insensitive GSK3 is normalized by β-blocker treatment. FASEB J. 2016;30:994–1001. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-279943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kempe DS, et al. Akt2/PKBbeta-sensitive regulation of renal phosphate transport. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;200:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhandaru M, et al. Decreased bone density and increased phosphaturia in gene-targeted mice lacking functional serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 3. Kidney Int. 2011;80:61–67. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu X, et al. Elevation in fibroblast growth factor 23 and its value for identifying subclinical atherosclerosis in first-degree relatives of patients with diabetes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34696. doi: 10.1038/srep34696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanks LJ, Casazza K, Judd SE, Jenny NS, Gutiérrez OM. Associations of fibroblast growth factor-23 with markers of inflammation, insulin resistance and obesity in adults. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garland JS, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with fibroblast growth factor-23 in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease patients. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vervloet MG, et al. MASTERPLAN group study Fibroblast growth factor 23 is associated with proteinuria and smoking in chronic kidney disease: An analysis of the MASTERPLAN cohort. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reyes-Garcia R, et al. FGF23 in type 2 diabetic patients: Relationship with bone metabolism and vascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:e89–e90. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahl P, et al. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study Group Earlier onset and greater severity of disordered mineral metabolism in diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:994–1001. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:98–107. doi: 10.1038/nri2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumann B, Salem HH, Boehm BO. Anti-inflammatory therapy in type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12:499–509. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rena G, Guo S, Cichy SC, Unterman TG, Cohen P. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor forkhead family member FKHR by protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17179–17183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wahl P, Wolf M. FGF23 in chronic kidney disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;728:107–125. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0887-1_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winther K, et al. Acute hyperinsulinemia is followed by increased serum concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 23 in type 2 diabetes patients. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2012;72:108–113. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2011.640407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thrailkill KM, et al. The impact of SGLT2 inhibitors, compared with insulin, on diabetic bone disease in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Bone. 2017;94:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riley MS, Schade DS, Eaton RP. Effects of insulin infusion on plasma phosphate in diabetic patients. Metabolism. 1979;28:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(79)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fruman DA, Rommel C. PI3K and cancer: Lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrd4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsitsipatis D, Gopal K, Steinbrenner H, Klotz L-O. FOXO1 cysteine-612 mediates stimulatory effects of the coregulators CBP and PGC1α on FOXO1 basal transcriptional activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;118:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greer EL, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2005;24:7410–7425. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamenický P, Mazziotti G, Lombès M, Giustina A, Chanson P. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, and the kidney: Pathophysiological and clinical implications. Endocr Rev. 2014;35:234–281. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bacchetta J, Cochat P, Salusky IB, Wesseling-Perry K. Uric acid and IGF1 as possible determinants of FGF23 metabolism in children with normal renal function. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:1131–1138. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2110-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito N, et al. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 23 in patients with acromegaly. Endocr J. 2007;54:481–484. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k06-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gardner J, Ashraf A, You Z, McCormick K. Changes in plasma FGF23 in growth hormone deficient children during rhGH therapy. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24:645–650. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2011.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Efthymiadou A, Kritikou D, Mantagos S, Chrysis D. The effect of GH treatment on serum FGF23 and Klotho in GH-deficient children. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174:473–479. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J, et al. Maternal PCaaC38:6 is associated with preterm birth–A risk factor for early and late adverse outcome of the offspring. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2016;41:250–257. doi: 10.1159/000443428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tyrrell J, et al. Early Growth Genetics (EGG) Consortium Genetic evidence for causal relationships between maternal obesity-related traits and birth weight. JAMA. 2016;315:1129–1140. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nair AV, et al. Loss of insulin-induced activation of TRPM6 magnesium channels results in impaired glucose tolerance during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113811109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song Y, et al. Insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion determined by homeostasis model assessment and risk of diabetes in a multiethnic cohort of women: The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1747–1752. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feger M, et al. The production of fibroblast growth factor 23 is controlled by TGF-β2. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4982. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05226-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saini RK, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 expression in bone cells: Evidence for primary and secondary mechanisms modulated by leptin and interleukin-6. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92:339–353. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9683-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfab T, et al. Low birth weight, a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in later life, is already associated with elevated fetal glycosylated hemoglobin at birth. Circulation. 2006;114:1687–1692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.625848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]