Abstract

Protein phosphorylation is critically important for many cellular processes, including progression through the cell cycle, cellular metabolism and differentiation. Isobaric labeling, e.g., Tandem Mass Tags (TMT), in phosphoproteomics workflows enables both relative and absolute quantitation of these phosphorylation events. Traditional TMT workflows identify peptides using fragment ions at the MS2 level and quantify reporter ions at the MS3 level. However, in addition to the TMT reporter ions, MS3 spectra also include fragment ions which can be used to identify peptides. Here, we describe using MS3 spectra for both phosphopeptide identification and quantification, a process which we term MS3-IDQ. To maximize quantified phosphopeptides, we optimize several instrument parameters, including the modality of mass analyzer (i.e., ion trap or Orbitrap), MS2 automatic gain control (AGC), and MS3 normalized collision energy (NCE) to achieve the best balance of identified and quantified peptides. Our optimized MS3-IDQ method included the following parameters for the MS3 scan: NCE=37.5 and AGC target = 1.5E5, scan range =100–2000. Data from the MS3 scan were complementary to that of the MS2 scan and the combination of these scans can increase phosphoproteome coverage by over 50%, thereby yielding a greater number of quantified and accurately localized phosphopeptides.

Keywords: Isobaric labeling, TMT, MS3 sequencing, phosphoproteomics

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Mass spectrometry-based strategies have been successful in defining global phosphorylation events. Protein phosphorylation has profound implications in cellular regulation and disease progression (1–4). In fact, alterations in phosphorylation events are typically more numerous than protein alterations (5–7), despite their low abundance. To investigate phosphopeptides via mass spectrometry, numerous fragmentation strategies – including CID, HCD, ETD, EThcD (8) - are available. When combined with high resolution Orbitrap technology, integrated methods can provide tremendous depth and specificity for analyzing complex phosphoprotein experiments. Much research has been directed toward developing optimized strategies for phosphoproteomic research. For example, researchers have claimed that the use of high energy collision dissociation (HCD) for peptide fragmentation – as used in Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) quantification in synchronous precursor selection MS3 (SPS-MS3) methods - generally generates higher quality MS/MS spectra for use in identification (9). In addition, strategies for phosphopeptide identification can be enhanced by the formation of neutral loss products, which can be used to trigger peptide fragmentation (10, 11).

Isobaric labeling in multiplexed quantitative proteomic assays have been very effective in measuring differences in phosphorylation events over multiple experimental conditions. These strategies include TMT-based quantitative workflows, which when analyzed using the MS3 approach has been shown to provide superior accuracy and precision for quantitative proteomics (12) and phosphoproteomics (13) experiments. In SPS-MS3, identification and quantification are detached in that peptides are identified by the MS2 scan, while quantified by the MS3 scan (MS2-ID/MS3-Q). This MS3 scan includes the reporter ions, as well as the fragments of SPS ions that were selected from the MS2 scan. In a standard SPS-MS3 analysis, the normalized collision energy (NCE) for the MS3 scan was optimized for TMT reporter ion fragmentation at a high value (e.g. NCE=55, HCD), which provides optimal quantification by yielding intense TMT reporter ion signal. Given that neutral loss formation is common in phosphopeptide analysis and is actually enhanced upon isobaric labeling (14), we sought to determine if the MS3 scan can be used beyond reporter ion quantification, more specifically, if sequencing information can be extracted from MS3 spectra with a lower NCE setting. While the SPS-MS3 approach is commonly used to measure reporter ion intensities, the MS3 spectra generated from TMT experiments also contain fragment ions with sequencing information when a lower NCE is used. However, these b and y ions in the MS3 spectra are typically ignored, as reporter ions are the focus of this scan.

Here we investigate MS3 spectra for phosphopeptide identification and quantification (MS3-IDQ). We optimized the instrument parameters to seek a balance between optimal identification, quantification and localization. We show further that our optimized method could be transferred successfully to another laboratory using different instrumentation, but yielding similar results. Our data show that the paired MS2 and MS3 scans are complimentary and that their combination provides greater analytical depth compared to either method alone. We establish that the MS3 spectra are valuable not only for reporter ion quantification, but also for peptide sequencing.

Experimental Section

Materials

Tandem mass tag (TMT) isobaric reagents were from ThermoFisher Scientific (Rockford, IL). Water and organic solvents were from J.T. Baker (Center Valley, PA). Lys-C was from Wako (Richmond, VA). Unless otherwise noted, all other chemicals were from ThermoFisher Scientific (Rockford, IL).

Sample Preparation

Whole mouse brain was solubilized in 4 ml lysis buffer (2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8, Roche complete protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors). Samples were reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylated with 15 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Samples were methanol/chloroform precipitated followed by denaturation in 4.5 mL of 8M urea in 20 mM EPPS (pH 8.5). Proteins were quantified using a bicinchoninic (BCA) assay. The urea concentration was diluted to 4M to digest proteins with Lys-C (enzyme-to-protein ratio of 1:75) overnight at room temperature. The following morning the concentration of urea was diluted further to 2M and digested with trypsin (Promega; Madison, WI) (1:75) for 6 hr at 37°C. Samples were acidified with formic acid to pH = 3. A quality control check was performed to determine the missed cleavage rate (< 15%) prior to clean up with a 100 mg SepPak (Waters) column. The SepPak eluents were dried using a vacuum centrifuge.

TMT labeling and phosphopeptide enrichment

TMTzero (Pierce, Rockford, IL) labeling was performed in 20 mM EPPS pH 8.5 and 0.8 mg of isobaric tag was added per 0.4 mg of peptide and allowed to react for 1 hour. A quality control check was performed to determine the labeling efficiency (>98%). The reaction was quenched by adding hydroxylamine to a final concentration of 0.5%. Peptides were then purified using tC18 Sep-Pak Cartridges (Waters, Milford MA) and then phosphopeptide enrichment was performed using the High-Select™ Fe-NTA Phosphopeptide Enrichment Kit (ThermoFisher, Rockford, IL). Phosphopeptides were eluted from the beads in 50 mM KH2PO4, pH10 followed by an additional round of Sep-Pak purification.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Phosphopeptides were reconstituted at 1 mg/ml of 3% acetonitrile/5% formic acid. 4 μg of phosphopeptides were injected onto a 30 cm, 100 μm ID column and peptides were separated using an EASY-nLC 1000 (ThermoFisher Scientific ). The column was packed with C18 1.8 μm beads with 12 nm pores (Sepax Technologies Inc., Newark, DE) and was heated to 60°C using an in-house built column oven. Samples were injected into an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). For fractionated samples, TMTzero-labeled IMAC-enriched phosphopeptides were injected onto a 1200 Agilent Series HPLC. Phosphopeptides were separated on a Zorbax 300 Extend-C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 3.5 μm) with a gradient from 8 to 44% B over 56 minutes with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. Buffer A consisted of 5% acetonitrile, 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8) and Buffer B was 90% acetonitrile, 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8). Fractions were pooled into 12 samples (15) and dried down, followed by C18 StageTip desalting prior to LC-MS/MS analysis.

Separation was in-line with the mass spectrometer and was performed using a 2 hr gradient of 6 to 26% acetonitrile in 0.125% formic acid at a flow rate of ~450 nL/min. Each analysis used an MS3-based method (12), which has been shown to reduce ion interference compared to MS2 quantification (16). For all experiments, the instrument was operated in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. Instrument parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Instrument parameters

| Std MS2/MS3 | OT-NL | OT-MSA | OT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS2 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mass analyzer | Ion Trap | Orbitrap | Orbitrap | Orbitrap |

| Activation type | CID | CID | CID | CID |

| Isolation window | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Collision energy | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Resolution | n/a | 15,000 | 15,000 | 15,000 |

| Scan rate | rapid | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| AGC | 1.80E+04 | 1.80E+04 | 1.80E+04 | 1.80E+04 |

| Injection time | 120 ms | 120 ms | 120 ms | 120 ms |

| MSA | no | no | 97.9763 | no |

| NL trigger | no | yes* | no | no |

|

| ||||

| MS3 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mass analyzer | Orbitrap | Orbitrap | Orbitrap | Orbitrap |

| Activation type | HCD | HCD | HCD | HCD |

| Charge state/Isolation window# | 2/1.3, 3/1.0, 4/0.8, 5/0.7 | 2/1.3, 3/1.0, 4/0.8, 5/0.7 | 2/1.3, 3/1.0, 4/0.8, 5/0.7 | 2/1.3, 3/1.0, 4/0.8, 5/0.7 |

| Collision energy | 55 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 37.5 |

| Resolution | 50,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| AGC | 1.20E+05 | 1.50E+05 | 1.50E+05 | 1.50E+05 |

| Injection time | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Scan range | 100–1000 | 100–2000 | 100–2000 | 100–2000 |

| # SPS | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Neutral loss trigger is charge state dependent: 2+: 48.9881 and 39.983, 3+: 32.6587 and 26.6553, 4+: 19.9915 and 24.494, 5+: 19.5952; 15.9932.

MS3 isolation window is charge state dependent.

MSA, multistage activation; n/a, not applicable; NL, neutral loss; OT, Orbitrap; AGC, automatic gain control; SPS, synchronous precursor selection.

Data Processing

A compilation of in-house software was used to convert mass spectrometric data (Thermo “.RAW” files) to mzXML format, as well as to correct monoisotopic m/z measurements and erroneous peptide charge state assignments. Assignment of MS/MS spectra was performed using the SEQUEST algorithm (17). Experiments used the Mouse UniProt database (downloaded July, 2014 with 49,018 protein entries). Reversed protein sequences were appended as well as known contaminants, such as human keratins. A false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 1% (for MS2 and MS3 scans) was achieved by applying the target-decoy database search strategy (18). Filtering was performed as described previously (19). We used a modified version of the Ascore algorithm to quantify the confidence with which each phosphorylation site could be assigned to a particular residue. Phosphorylation sites with Ascore values > 13 (P ≤ 0.05) were considered confidently localized to a particular residue (20). Raw files are available upon request.

Results and Discussion

We optimized our methods using a sample of mouse brain lysate as it is abundant in phosphopeptides. We used the IMAC-based High-Select Fe-NTA Phosphopeptide Enrichment Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) to enrich for phosphopeptides and labeled our sample with TMTzero. Quality control checks ensured adequate digestion (<15% missed cleavages) and acceptable labeling (>98% labeling efficiency). For most experiments, we used this unfractionated TMTzero-labeled phosphopeptide sample to optimize instrument parameters so as to obtain the highest number of identified, quantified, and localized phosphopeptides for the MS3-IDQ strategy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. MS3-IDQ Phosphopeptide Workflow.

To generate our phosphopeptide sample, intact mouse brain was solubilized in SDS lysis buffer. Following reduction, alkylation and digestion, phosphopeptides were enriched using IMAC and labeled with TMTzero. Fusion Lumos MS settings were adjusted to allow for optimal phosphopeptide identification and localization at both the MS2 and MS3 stage.

In a typical TMT experiment, phosphopeptides are identified and localized at the MS2 stage using CID fragmentation, while taking advantage of the fast scan rate of ion trap analyzers. However, TMT requires HCD for efficient fragmentation of reporter ions. Thus, our goal here was to optimize instrument parameters to achieve the best possible spectra for HCD analysis to identify and quantify phosphopeptides at the MS3-stage. First, we aimed to optimize the HCD collision energy to provide the highest number of protein identifications at the MS3 stage. As such, we compared the number of quantified peptides for normalized collision energies, ranging from 25 to 55, using HCD fragmentation (Figure 2). We found that the optimal HCD collision energy setting was between 35 and 37.5. Although setting the NCE to 35 resulted in slightly more quantified proteins, we selected an NCE setting of 37.5 as reporter ions were generally more intense for this NCE setting compared with an NCE setting of 35. Surprisingly, when we investigated MS2-based identification and quantification, a lower energy (NCE=30) produced superior results within the range examined (Supplemental Figure 1). However, we used an NCE setting of 37.5 to ensure high quality phosphopeptide identification and quantification for our MS3-IDQ analysis.

Figure 2. Optimizing MS3-NCE for MS3-IDQ.

We varied the HCD Normalized Collision Energy (NCE) to determine the optimal settings to use in MS3 spectra-based quantification. Error bars represent ± standard deviation (n=2).

We further optimized phosphopeptide quantification using different fragmentation settings. The Orbitrap Tribrid family of mass spectrometers allows for collection of MS2 data in either an ion trap (low resolution) or Orbitrap (high resolution) mass analyzer. In addition, several strategies have been developed that can directly trigger fragmentation of a phosphopeptide, namely the use of high-resolution Multi-Stage Activation (MSA) (10) and the formation of a Neural Loss (NL) product (11). As such, we compared variants of our method using Multi-Stage Activation (OT-MSA) and Triggered Neutral Loss (OT-NL) with standard ion trap (IT) and Orbitrap (OT) analyzer settings using MS3-based methods (Supplemental Figure 2A). We quantified the most phosphorylated peptides using OT-MSA, followed by OT, then IT and finally OT-NL, when using normalized collision energy (NCE) of 55 and an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 1.2E5. Using MS3 identification and quantification (MS3-IDQ), with NCE=37.5 and AGC target = 1.5E5, we observed similar quantification throughout, with slightly more phosphopeptides quantified in OT-NL and less in OT-MSA. Combining MS2 and MS3 search results and taking only non-redundant phosphopeptides revealed OT-MSA produced the most quantified phosphopeptides, followed by OT and OT-NL. We show that using Neutral Loss Triggering increased the number of quantified phosphopeptides at the MS3 stage compared to OT-MSA, however, the combination of MS2 and MS3 scans using OT-MSA resulted in a greater number of identified phosphopeptides. We examined the overlap of quantified phosphopeptides between the MS2 and MS3 scans for each of the four methods tested, which revealed 30–40% of the total peptides were unique to the MS3 scan (Supplemental Figure 2B). In addition, we tested several MS2 AGC and MS3 NCE settings (Supplemental Figure 2C). As observed previously, we note decreased phosphopeptide identifications at MS3-NCE settings greater than 37.5. In addition, MS2 AGC did not substantially affect phosphopeptide identifications. However, to account for lower reporter ion intensity in MS3-IDQ (due to using NCE=37.5 relative to standard NCE=55), we increased the MS3 AGC setting to ensure a high level of quantified phosphopeptides. More specifically, while standard methods used MS3 AGC=1.2E5 with NCE=55, we used MS3 AGC=1.5E5 and NCE=37.5 for the MS3-IDQ analysis. In addition to these parameters, more rigorous testing of additional parameters may further optimize our method.

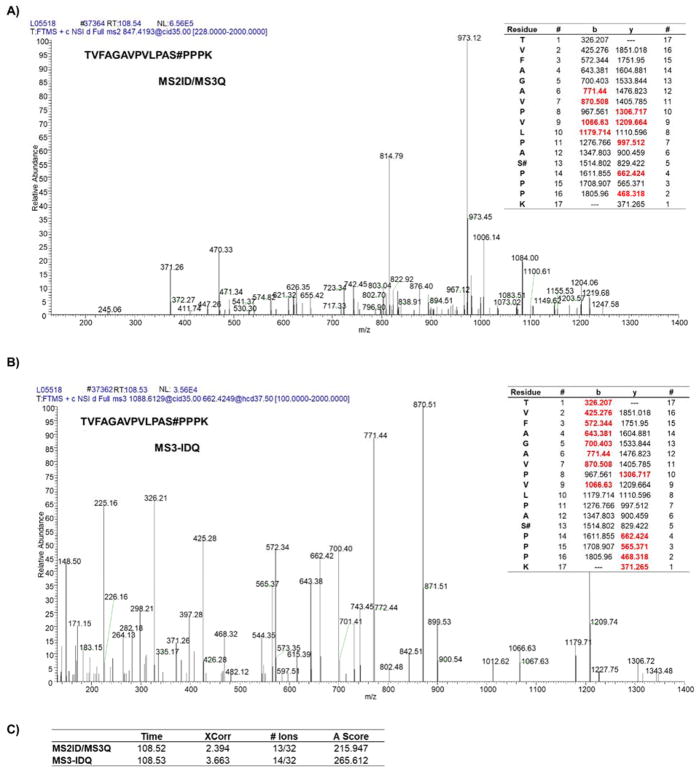

Examining the spectra, we note that the data obtained from the MS2 and MS3 scans are complementary. For example, in MS2 and MS3 spectra of the same peptide, common and unique ions are observed in both MS2 (Figure 3A) and MS3 (Figure 3B) spectra. As such, combining the two scans prior to database searching may yield synergistically optimal results (i.e., a case where both spectra fail, but their merged spectrum passes). In fact, in the example peptide (doubly charged, TVFAGAVPVLPAS#PPPK), the MS2 and MS3 scans share the same retention time, however, the MS3-IDQ search had higher XCorr value, number of ions identified over number possible, and localization score (AScore) (Figure 3C). It is noteworthy that the MS3 scan determined the 326 Th ion to represent a threonine - the only other residue in the sequence that could be phosphorylated – thereby increasing confidence in its localization. As such, each scan can serve to validate and supplement the other, together providing superior results compared to either scan alone. We also include two exemplar phosphopeptides, RGPGAAGPG ASGS#GHGEER (Supplemental Figure 3A) and GHAGGQRPEPSS#PDGPAPPTRR (Supplemental Figure 3B) that were only identified in the MS3 scan and not the MS2 scan within the same file. A precedent exists for analyzing paired scans, but not in the context of phosphopeptides nor for data acquired using the SPS-MS3 technique (21).

Figure 3. Complementarity of MS2 and MS3 scans.

Example of a phosphopeptide (TVFAGAVPVLPAS#PPPK, 2+) for which A) MS2 and B) MS3 scans each detect unique fragment ions, which would increase the quality of the identification. C) Table summarizing characteristics of both scans.

Our initial experiments, including those described above, used an unfractionated sample. However, performing off-line HPLC fractionation achieves a greater depth of coverage for proteomics datasets. We used our optimized MS2 and MS3 settings on a fractionated phosphopeptide sample. The 12 fractions were analyzed with our high resolution MS2/optimized MS3 OT-method. Like the unfractionated data, the identifications obtained from the MS3 scans were complimentary to those from the MS2 scans. This fractionated (and therefore less complex) sample shows sequencing the MS3 scan provides more unique, quantified, and localized phosphopeptides than the MS2 scan (Figure 4A). The identifications from the two scan types are complimentary as the combination of the MS2 and MS3 scans provided substantially more identifications than either scan type alone.

Figure 4. Fractionated sample shows that MS3-IDQ provides additional unique, quantified, and localized phosphopeptides.

A) In a fractionated study, we note that the MS3 scan provided more identifications than the MS2 scan. B) An unfractionated TMT-labeled phosphopeptide sample was analyzed in two separate laboratories and showed increase in quantified phosphopeptides with lower NCE. Normalized collision energy settings of 37.5 and 55 for MS3 fragmentation were compared between laboratories. Measurements were performed in triplicate.

Finally, we aimed to show that our findings were generalizable across labs and instruments. We used our optimized strategy and compared the number of quantified, unique phosphopeptides at the MS2 and MS3 stage. We compared the normalized collision energies of 37.5 (optimized for MS3-IDQ) and 55 (commonly used for MS2-ID/MS3-Q) between two laboratories, both using Orbitrap Fusion Lumos instruments (Figure 4B). Examining the distributions of the TMT summed signal-to-noise showed minor differences between the chosen NCE regardless of the instrument (Supplemental Figure 4). Our findings were consistent between laboratories, that is, an NCE of 37.5 at the MS3 stage for MS3-IDQ analysis resulted in a greater number of quantified phosphopeptides, than the traditionally used NCE of 55.

Conclusions

In this study, we optimized MS3 settings for phosphopeptide identification and quantification. We discovered that using the HCD MS3 collision energy of 37.5 and increasing the scan range to 2000 m/z provided useful phosphorylation site identification and localization information in addition to quantification using typical reporter ion intensities. The optimized method provided 50–70% higher localized and quantified phosphopeptides compared to standard SPS-MS3 method parameters. These findings agreed with an inter-laboratory comparison of different instruments. In fractionated samples, we found the MS3 scan provided more information than the MS2 scan. The data obtained from the MS3 scans were complimentary to those of MS2, and thus their combination provided superior results compared to either method alone. Our data show that MS3 spectra can provide additional phosphopeptide identification beyond only quantifying reporter ion intensities, and thus, the use of MS3-IDQ is a robust method that can increase depth of phosphoproteomic analysis. We anticipate the future development of data collection and analytical methods that take advantage of the non-reporter ion information that is currently neglected, yet provided gratis in the MS3 scan.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Optimizing MS2-NCE for HCD MS2 quantification. We varied the HCD Normalized Collision Energy (NCE) to determine the optimal settings to use in MS2 spectra-based quantification and compared that optimal value to the optimum NCE for MS3.

Supplemental Figure 2: Optimizing instrument parameters. A) We note the effects of changing the mass analyzer and neutral loss fragmentation on identified phosphopeptides. B) Venn diagrams comparing MS2 and MS3 scans for each of the methods tested. C) We also tested several MS2 AGC and MS3 NCE settings. MSA, multistage activation; NL, neutral loss; AGC, automatic gain control; NCE, normalized collision energy.

Supplemental Figure 3: Examples peptides identified only by MS3 scan. Examples of two phosphopeptides A) RGPGAAGPGASGS#GHGEER and B) GHAGGQRPEPSS#PDGPAPPTRR which were identified by the MS3 scan, but not by the MS2 scan.

Supplemental Figure 4: Average TMT signal-to-noise for MS3 normalized collision energies setting of 37.5 and 55. An unfractionated TMT-labeled phosphopeptide sample was analyzed in two separate laboratories and showed increase in quantified phosphopeptides. Normalized collision energies setting of 37.5 and 55 for MS3 fragmentation were compared between laboratories. Measurements were performed in triplicate.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Steven P. Gygi and the members of the Gygi Lab, as well the members of the Laboratories for Systems Pharmacology at Harvard Medical School for discussions and support. M.J.B. and R.A.E. were supported by NIH grants P50-GM107618 and U54-HL127365. J.A.P. was supported by NIH/NIDDK grant K01-DK098285.

References

- 1.Repici M, Mare L, Colombo A, Ploia C, Sclip A, Bonny C, Nicod P, Salmona M, Borsello T. c-Jun N-terminal kinase binding domain-dependent phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 and balancing cross-talk between c-Jun N-terminal kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways in cortical neurons. Neuroscience. 2009;159(1):94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahk YY, Cho IH, Kim TS. A cross-talk between oncogenic Ras and tumor suppressor PTEN through FAK Tyr861 phosphorylation in NIH/3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377(4):1199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katsanakis KD, Pillay TS. Cross-talk between the two divergent insulin signaling pathways is revealed by the protein kinase B (Akt)-mediated phosphorylation of adapter protein APS on serine 588. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):37827–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burchfield JG, Lennard AJ, Narasimhan S, Hughes WE, Wasinger VC, Corthals GL, Okuda T, Kondoh H, Biden TJ, Schmitz-Peiffer C. Akt mediates insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Ndrg2: evidence for cross-talk with protein kinase C theta. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):18623–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulo JA, Gaun A, Gygi SP. Global Analysis of Protein Expression and Phosphorylation Levels in Nicotine-Treated Pancreatic Stellate Cells. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(10):4246–56. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paulo JA, Gygi SP. A comprehensive proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis of yeast deletion mutants of 14-3-3 orthologs and associated effects of rapamycin. Proteomics. 2015;15(2–3):474–86. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paulo JA, McAllister FE, Everley RA, Beausoleil SA, Banks AS, Gygi SP. Effects of MEK inhibitors GSK1120212 and PD0325901 in vivo using 10-plex quantitative proteomics and phosphoproteomics. Proteomics. 2015;15(2–3):462–73. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frese CK, Zhou H, Taus T, Altelaar AF, Mechtler K, Heck AJ, Mohammed S. Unambiguous phosphosite localization using electron-transfer/higher-energy collision dissociation (EThcD) J Proteome Res. 2013;12(3):1520–5. doi: 10.1021/pr301130k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jedrychowski MP, Huttlin EL, Haas W, Sowa ME, Rad R, Gygi SP. Evaluation of HCD- and CID-type fragmentation within their respective detection platforms for murine phosphoproteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(12):M111009910. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Schwartz JC, Hunt DF, Coon JJ. A neutral loss activation method for improved phosphopeptide sequence analysis by quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2004;76(13):3590–8. doi: 10.1021/ac0497104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Gygi SP. Evaluation of the utility of neutral-loss-dependent MS3 strategies in large-scale phosphorylation analysis. Proteomics. 2008;8(21):4444–52. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ting L, Rad R, Gygi SP, Haas W. MS3 eliminates ratio distortion in isobaric multiplexed quantitative proteomics. Nat Methods. 2011;8(11):937–40. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erickson BK, Jedrychowski MP, McAlister GC, Everley RA, Kunz R, Gygi SP. Evaluating multiplexed quantitative phosphopeptide analysis on a hybrid quadrupole mass filter/linear ion trap/orbitrap mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2015;87(2):1241–9. doi: 10.1021/ac503934f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everley RA, Huttlin EL, Erickson AR, Beausoleil SA, Gygi SP. Neutral Loss Is a Very Common Occurrence in Phosphotyrosine-Containing Peptides Labeled with Isobaric Tags. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(2):1069–1076. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paulo JA, O’Connell JD, Everley RA, O’Brien J, Gygi MA, Gygi SP. Quantitative mass spectrometry-based multiplexing compares the abundance of 5000 S. cerevisiae proteins across 10 carbon sources. J Proteomics. 2016;148:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paulo JA, O’Connell JD, Gygi SP. A Triple Knockout (TKO) Proteomics Standard for Diagnosing Ion Interference in Isobaric Labeling Experiments. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2016;27(10):1620–5. doi: 10.1007/s13361-016-1434-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5(11):976–89. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4(3):207–14. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAlister GC, Nusinow DP, Jedrychowski MP, Wuhr M, Huttlin EL, Erickson BK, Rad R, Haas W, Gygi SP. MultiNotch MS3 enables accurate, sensitive, and multiplexed detection of differential expression across cancer cell line proteomes. Anal Chem. 2014;86(14):7150–8. doi: 10.1021/ac502040v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huttlin EL, Jedrychowski MP, Elias JE, Goswami T, Rad R, Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Haas W, Sowa ME, Gygi SP. A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell. 2010;143(7):1174–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan Y, Kusalik AJ, Wu FX. De novo peptide sequencing using CID and HCD spectra pairs. Proteomics. 2016;16(20):2615–2624. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Optimizing MS2-NCE for HCD MS2 quantification. We varied the HCD Normalized Collision Energy (NCE) to determine the optimal settings to use in MS2 spectra-based quantification and compared that optimal value to the optimum NCE for MS3.

Supplemental Figure 2: Optimizing instrument parameters. A) We note the effects of changing the mass analyzer and neutral loss fragmentation on identified phosphopeptides. B) Venn diagrams comparing MS2 and MS3 scans for each of the methods tested. C) We also tested several MS2 AGC and MS3 NCE settings. MSA, multistage activation; NL, neutral loss; AGC, automatic gain control; NCE, normalized collision energy.

Supplemental Figure 3: Examples peptides identified only by MS3 scan. Examples of two phosphopeptides A) RGPGAAGPGASGS#GHGEER and B) GHAGGQRPEPSS#PDGPAPPTRR which were identified by the MS3 scan, but not by the MS2 scan.

Supplemental Figure 4: Average TMT signal-to-noise for MS3 normalized collision energies setting of 37.5 and 55. An unfractionated TMT-labeled phosphopeptide sample was analyzed in two separate laboratories and showed increase in quantified phosphopeptides. Normalized collision energies setting of 37.5 and 55 for MS3 fragmentation were compared between laboratories. Measurements were performed in triplicate.