Abstract

Background

Prior studies have supported an inverse association between physical activity and colon cancer risk, and suggest that higher physical activity may also improve cancer survival. Among participants in a phase III adjuvant trial for stage III colon cancer, we assessed the association of physical activity around the time of cancer diagnosis with subsequent outcomes.

Methods

Before treatment arm randomization (FOLFOX or FOLFOX+cetuximab), study participants completed a questionnaire including items regarding usual daily activity level and frequency of participation in recreational physical activity (N=1992). Using multivariable Cox models, we calculated hazard ratios (HR) for associations of aspects of physical activity with disease-free (DFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results

Over follow-up, 505 participants died and 541 experienced a recurrence. Overall, 75% of participants reported recreational physical activity at least several times a month; for participants who reported physical activity at least that often (vs. once a month or less), the HRs for DFS and OS were 0.82 (95% CI: 0.69-0.99) and 0.76 (95%CI: 0.63-0.93), respectively. There was no evidence of material effect modification in these associations by patient or tumor attributes, except that physical activity was more strongly inversely associated with OS in patients with stage T3 vs. T4 tumors (P-interaction=0.03).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that higher physical activity around the time of colon cancer diagnosis may be associated with more favorable colon cancer outcomes.

Impact

Our findings support further research on whether colon cancer survival may be enhanced by physical activity.

Keywords: colon cancer, physical activity, survival, BRAF, KRAS, mismatch repair

INTRODUCTION

Each year in the United States, greater than 50,000 deaths are attributed to colorectal cancer (1). Many more such deaths are likely prevented by virtue of early detection and curative therapy. To further reduce the mortality burden of colorectal cancer, it is important to identify factors associated with prognosis among colon or rectal cancer patients, particularly factors that may be intervened upon or modified. Although stage at diagnosis remains the strongest known predictor of colorectal cancer survival outcomes (1, 2), and certain tumor attributes (e.g., DNA mismatch repair status, BRAF mutation status) have also been consistently associated with prognosis (2–7), increasing evidence suggests that modifiable lifestyle factors may also play a role survival (8–13). One such factor that may plausibly be associated with colorectal cancer survival is physical activity (12–14).

A sizable literature supports the association between physical activity and reduced risk of developing colon cancer (15, 16). Among numerous plausible mechanisms underlying this association with risk, physical activity contributes to reductions in circulating levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1, both of which inhibit apoptosis and promote cell proliferation in colon tumor cells (17–23). Such mechanisms could also be expected to contribute to a relationship between physical activity and colon cancer survival. In a recent meta-analysis, Wu et al. found significantly more favorable disease-specific and overall survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis associated with any vs. no exercise and with high vs. low physical activity levels, regardless of whether physical activity was ascertained with regard to the time period before or after cancer diagnosis (14). However, questions remain as to whether the association between physical activity and colon cancer survival outcomes varies across case groups defined by patient and/or tumor characteristics.

Using data from a large, multicenter clinical trial of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer, we evaluated the association of physical activity patterns with disease-free survival, overall survival, and time-to-recurrence, with consideration for possible heterogeneity according to tumor and patient attributes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

N0147, led by the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) (now a part of the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology), is a multicenter phase III randomized trial of adjuvant 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and leucovorin (FOLFOX) with or without cetuximab in patients with resected stage III colon cancer (24). A total of 3,397 patients were enrolled, including 2,686 who were randomized to the primary treatment comparison arms (FOLFOX vs. FOLFOX plus cetuximab). The present study is limited to N0147 participants enrolled in the primary treatment comparison arms who had completed a patient questionnaire at the baseline study visit, and, specifically, answered physical activity questions (N=1,992). All participants signed Institutional Review Board-approved, protocol-specific informed consent forms in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines.

Ascertainment of Physical Activity

A patient questionnaire eliciting information on a variety of risk factors, including smoking history, alcohol consumption patterns, and usual physical activity patterns was administered to N0147 participants prior to treatment. With respect to physical activity, participants were asked to report on their usual level of physical activity “during a routine day” (almost none/mild activity/moderate/heavy activity). They were also asked to report on how often during their “free time” they took part in “any” physical activity (never/about once a month/several times a month/several times a week/daily). In addition to the question of any free-time physical activity, participants were asked separate questions about the frequency of their participation in “moderate” physical activity (e.g., golf, gardening, long walks, bowling) and “vigorous” physical activity (e.g., jogging, racket sports, swimming, aerobics) during their free time. A specific reference time point was not provided in the physical activity questionnaire items; however, these questions were administered at a time shortly following surgical resection for stage III colon cancer, and prior to receipt of chemotherapy.

Tumor Characteristics

Tumor tissue blocks were collected from the original surgical resection for study participants. Testing for DNA mismatch repair status (MMR), as well as KRAS- and BRAF-mutation status, was conducted centrally at the Mayo Clinic using previously described methods. Briefly, MMR status was determined by immunohistochemical assessment of hMLH-1, hMSH-2, and hMSH-6 (25); patients with tumors exhibiting a loss of expression for any of these proteins were classified as having tumors with defective MMR (dMMR), whereas patients with no loss of expression were classified as having tumors with proficient MMR (pMMR). DNA isolated from tumor specimens was used to test for 7 mutations in KRAS exon 2 hotspot codons 12 and 13, and for the BRAF V600E mutation (26).

Classification of Outcomes

We evaluated associations with respect to three overlapping clinical outcomes: time-to-recurrence (TTR), overall survival (OS), and disease-free survival (DFS). TTR was defined as the time from randomization to first documented disease recurrence; participants who died before a recurrence were censored at their last disease assessment date. OS was defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause. DFS was defined as the time from randomization to the first documented cancer recurrence or death from any cause, whichever came first. Patients were censored at 5 years post-randomization in analyses of DFS and TTR, and censored at 8 years post-randomization in analyses of OS. The present analysis was based on follow-up through December 3, 2014.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated associations between the following self-reported physical activity attributes and colon cancer outcomes: usual daily physical activity, frequency of any free-time physical activity, frequency of moderate intensity physical activity, frequency of vigorous physical activity. For the latter three frequency variables, based on observed similarities in point estimates and small numbers, we grouped together exposure categories for those who reported never participating in physical activity and those who participated only about once a month; similarly, we grouped together exposure categories for those who reported participating in free-time physical activity several times a month to daily.

The distribution of patient and tumor attributes was tabulated and compared across grouped categories of physical activity frequency using Wilcoxon (27) (continuous) and chi-squared (28) (categories) tests. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models (29, 30) to assess associations between physical activity variables and study outcomes, with adjustment for the following attributes: age at diagnosis, sex, T-stage, N-stage, Eastern Cooperative Group performance score, histologic grade, tumor location, KRAS-mutation status, BRAF-mutation status, MMR status, body mass index (BMI), smoking frequency, alcohol use, and treatment assignment. Confounders were selected a priori and were included in the analytic model as parameterized in Table 1. Participants with missing data on model covariates were excluded from multivariable analyses (N=211). We also conducted analyses stratified by each of the aforementioned adjustment variables and evaluated potential interaction by these variables in the association between physical activity and patient outcomes. Proportional hazards assumptions were verified by testing for a non-zero slope of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals on ranked failure times (31). Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study participants from North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial N0147 according to reported participation in free time physical activity*

| Total (N=1992) N (column %) |

Never/About once a month (N=487) N (column %) |

More than once a month (N=1505) N (column %) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 0.73 | |||

| FOLFOX | 1020 (51%) | 246 (51%) | 774 (51%) | |

| FOLFOX+cetuximab | 972 (49%) | 241 (49%) | 731 (49%) | |

| Age at randomization | 0.04 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 58.1 (11.3) | 59.1 (10.9) | 57.8 (11.4) | |

| Range | (19.0-86.0) | (25.0-86.0) | (19.0-85.0) | |

| Race | 0.006 | |||

| White | 1721 (86%) | 407 (84%) | 1314 (87%) | |

| Non-white | 243 (12%) | 77 (16%) | 166 (11%) | |

| Unknown | 28 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 25 (2%) | |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 952 (48%) | 265 (54%) | 687 (46%) | |

| Male | 1040 (52%) | 222 (46%) | 818 (54%) | |

| Tumor site | 0.51 | |||

| Missing | 26 | 5 | 21 | |

| Proximal | 935 (48%) | 223 (46%) | 712 (48%) | |

| Distal | 1031 (52%) | 259 (54%) | 772 (52%) | |

| T-Stage | 0.16 | |||

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| T1/T2 | 282 (14%) | 64 (13%) | 218 (14%) | |

| T3 | 1492 (75%) | 379 (78%) | 1113 (74%) | |

| T4 | 217 (11%) | 43 (9%) | 174 (12%) | |

| Lymph node involvement | 0.58 | |||

| 1-3 | 1179 (59%) | 283 (58%) | 896 (60%) | |

| ≥4 | 813 (41%) | 204 (42%) | 609 (40%) | |

| Performance score | 0.003 | |||

| 0 | 1522 (76%) | 348 (71%) | 1174 (78%) | |

| 1-2 | 470 (24%) | 139 (29%) | 331 (22%) | |

| Mismatch repair status (MMR) | 0.38 | |||

| Missing | 83 | 25 | 58 | |

| Proficient | 1679 (88%) | 401 (87%) | 1278 (88%) | |

| Deficient | 230 (12%) | 61 (13%) | 169 (12%) | |

| KRAS/BRAF mutation status | 0.58 | |||

| Missing | 144 | 32 | 112 | |

| KRAS-wildtype/BRAF-wildtype | 941 (51%) | 222 (49%) | 719 (51%) | |

| KRAS-mutated/BRAF-wildtype | 653 (35%) | 168 (37%) | 485 (35%) | |

| KRAS-wildtype/BRAF-mutated | 254 (14%) | 65 (14%) | 189 (14%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <0.001 | |||

| Missing | 7 | 1 | 3 | |

| <20 | 77 (4%) | 15 (3%) | 62 (4%) | |

| 20-24.9 | 479 (24%) | 88 (18%) | 391 (26%) | |

| 25-29.90 | 731 (37%) | 165 (34%) | 566 (38%) | |

| ≥30.0 | 698 (35%) | 218 (45%) | 480 (32%) | |

| Smoking history | 0.07 | |||

| Missing | 9 | 3 | 6 | |

| Never | 935 (47%) | 216 (45%) | 719 (58%) | |

| Former | 900 (45%) | 221 (46%) | 679 (45%) | |

| Current | 148 (7%) | 47 (10%) | 101 (7%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | <0.001 | |||

| Missing | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| Never | 604 (30%) | 165 (34%) | 439 (29%) | |

| Former | 597 (30%) | 166 (34%) | 431 (29%) | |

| Current | 784 (39%) | 153 (32%) | 631 (42%) |

Table excludes N=47 participants who completed the study questionnaire but did not answer the study question pertaining to participation in any free-time physical activity, some of whom provided responses to other physical activity questions.

All statistical analyses were performed by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Approximately 75% of study participants reported participating in any physical activity during their free time at least several times a month; more specifically, 68% reported participating in moderate intensity physical activity more than once a month and 16% reported participating in vigorous intensity physical activity more than once a month. Compared to those who reported no participation in free-time physical activity or participation only once a month, participants who took part in any physical activity more than once a month were slightly younger (P=0.04), more likely to be male (P<0.001), had lower ECOG performance scores (P=0.003), were more likely to consume alcohol (P<0.001), and had a lower BMI (P<0.001) (Table 1).

Over the course of study follow-up, 28% (N=505) of study participants died and 30% (N=541) experienced a disease recurrence (89% of whom subsequently died during follow-up). The median follow-up time was 6.9 years (IQR: 6.1 – 7.6 years). After multivariable adjustment, there was no association between usual daily activity level and any of the evaluated outcomes (Table 2). However, reported participation in free-time physical activity more than once a month versus once a month or less was significantly associated with OS [hazard ratio (HR)= 0.76, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.63-0.93, P=0.007) and DFS (HR=0.82, 95% CI: 0.69-0.99, P=0.04); these associations persisted when we restricted the comparison group to those who reported no participation in any free-time physical activity (HR=0.73 and HR=0.77, respectively). Reported participation in moderate intensity physical activity more than once a month was similarly associated with outcomes, particularly with respect to OS (HR=0.80, 95% CI: 0.66-0.96, P=0.02). Observed associations between vigorous intensity physical activity and patient outcomes were more modest and not statistically significant, as were associations between any or moderate intensity physical activity and TTR.

TABLE 2.

Association of daily activity levels and participation in physical activity with colon cancer outcomes*

| Overall Survival

|

Disease-Free Survival

|

Time-to-Recurrence

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N Events/Total N | HR (95% CI) | N Events/Total N | HR (95% CI) | N Events/Total N | HR (95% CI) | |

| Usual daily activity level | ||||||

| Almost no activity | 23/84 | 1.0 (ref) | 30/84 | (ref) | 30/84 | 1.0 (ref) |

| Mild activity only | 220/738 | 1.20 (0.78-1.86) | 253/738 | 1.12 (0.76-1.64) | 253/738 | 1.15 (0.76-1.74) |

| Moderate activity | 207/755 | 1.10 (0.71-1.71) | 251/755 | 1.09 (0.74-1.61) | 251/755 | 1.16 (0.76-1.75) |

| Heavy activity | 61/225 | 1.06 (0.65-1.73) | 70/225 | 0.99 (0.64-1.54) | 70/225 | 1.05 (0.66-1.68) |

| p-value | 0.66 | 0.80 | 0.83 | |||

| Participation in any free-time physical activity | ||||||

| Never/once a month | 156/440 | 1.0 (ref) | 173/440 | (ref) | 173/440 | 1.0 (ref) |

| At least several times a month | 349/1341 | 0.76 (0.63-0.93) | 426/1341 | 0.82 (0.69-0.99) | 426/1341 | 0.86 (0.70-1.04) |

| p-value | 0.007 | 0.04 | 0.12 | |||

| Participation in moderate-intensity free-time physical activity | ||||||

| Never/once a month | 199/580 | 1.0 (ref) | 218/580 | 1.0 (ref) | 218/580 | 1.0 (ref) |

| At least several times a month | 308/1219 | 0.80 (0.66-0.96) | 383/1219 | 0.88 (0.74-1.05) | 383/1219 | 0.93 (0.77-1.12) |

| p-value | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.46 | |||

| Participation in vigorous-intensity free-time physical activity | ||||||

| Never/once a month | 442/1517 | 1.0 (ref) | 524/1517 | 1.0 (ref) | 524/1517 | 1.0 (ref) |

| At least several times a month | 68/290 | 0.93 (0.72-1.22) | 81/290 | 0.89 (0.70-1.13) | 81/290 | 0.91 (0.71-1.17) |

| p-value | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.47 | |||

Hazard ratios (HR) adjusted for age, sex, T-stage, N-stage, performance score, histologic grade, tumor location, KRAS/BRAF somatic mutation status, mismatch repair status, body mass index, smoking history, and alcohol consumption. Participants with missing data on model covariates or physical activity variables are excluded from multivariable analyses and table counts. Sample size differs across variables due to variability in missingness of physical activity variables.

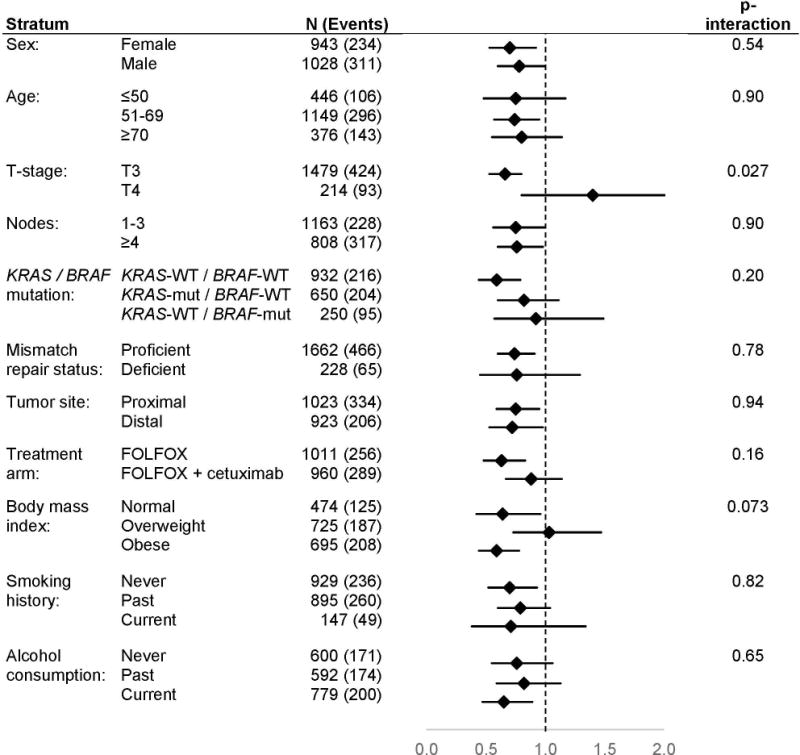

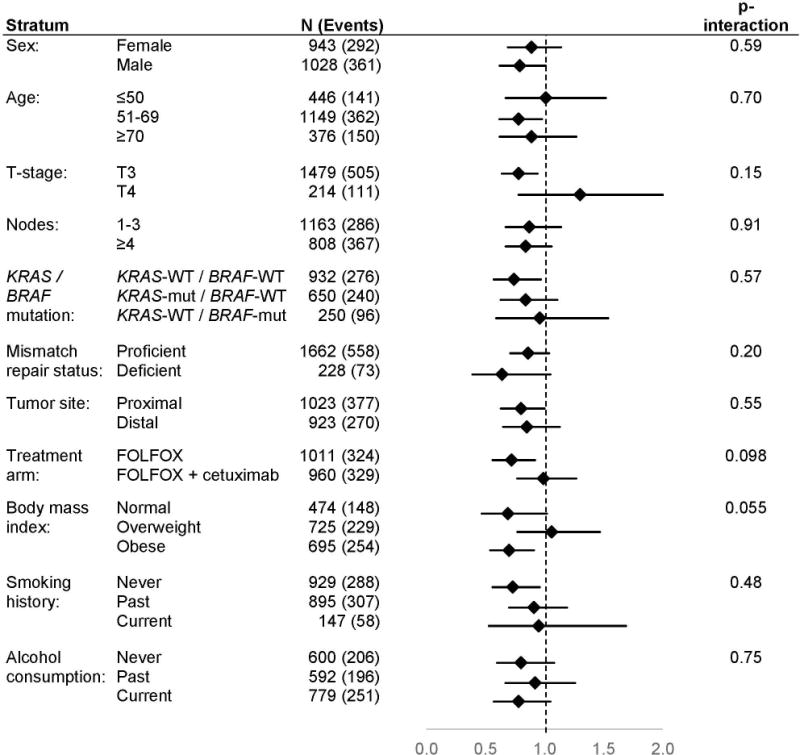

In stratified analyses, the association between reported participation in any free-time physical activity more than once a month (vs. once a month or less) and more favorable OS appeared to be restricted to those with smaller tumors (stage T3 vs. T4, P-interaction=0.03). This association was also suggestively but not significantly stronger among those who were normal weight or obese (but not overweight, P-interaction=0.07), among those with tumors not exhibiting mutations in BRAF or KRAS (vs. with a somatic mutation in either gene, P-interaction=0.20), and among those who received FOLFOX without cetuximab (vs. with cetuximab, P-interaction=0.16) (Figure 1). Similar patterns of difference were evident in analyses of DFS (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Physical activity and overall survival.

provides a comparison of overall survival between participants who reported taking part in any free-time physical activity more than once a month (vs. once a month or less) according to patient and tumor characteristics. Analyses are adjusted for age, treatment, sex, smoking history, performance score, alcohol consumption, and body mass index. Overall survival is defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause, whichever came first. Abbreviations: wt, wildtype; mut, mutated; pMMR, proficient mismatch repair; dMMR, deficient mismatch repair.

Figure 2. Physical activity and disease-free survival.

provides a comparison of disease-free survival between participants who reported taking part in any free-time physical activity more than once a month (vs. once a month or less) according to patient and tumor characteristics. Analyses are adjusted for age, treatment, sex, smoking history, performance score, alcohol consumption, and body mass index. Disease-free survival is defined as the time from randomization to the first documented cancer recurrence or death from any cause, whichever came first. Abbreviations: wt, wildtype; mut, mutated; pMMR, proficient mismatch repair; dMMR, deficient mismatch repair.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of clinical trial participants with stage III colon cancer, we observed a modest association between physical activity and colon cancer outcomes, suggesting more favorable DFS and OS in individuals who reported participating in recreational physical activity more than once a month around the time of colon cancer diagnosis. These associations were consistent across most participant subgroups defined by demographic, tumor, and lifestyle factors.

Similar to our overall findings, most previous studies into the association between pre-diagnostic physical activity and subsequent colorectal cancer outcomes have suggested modestly more favorable survival in those who were physically active than in those who were not active or minimally active during this time (12, 13, 32–38). Most recently, Walter et al. reported a significant inverse association between average leisure time activity in the years immediately preceding colorectal cancer diagnosis and subsequent OS, and a more modest, borderline significant inverse association with DFS (38). Although physical activity was parameterized in quartiles of MET-hours/week in that study, point estimates comparing outcomes for those in upper quartiles of physical activity to those in the lowest quartile (HROS=0.64 to 0.81, HRDFS=0.78 to 0.92) are within the range of point estimates reported here. Previous meta-analyses have similarly reported modestly more favorable OS and disease-specific survival associated with participation in any vs. no physical activity among individuals with colorectal cancer, with summary point estimates of 0.74 for OS and 0.75 for disease-specific survival (32–34). However, this pattern of association has not been uniformly observed across all studies (39).

To our knowledge, only one prior study has investigated the association between physical activity and colon cancer outcomes with consideration for the tumor attributes evaluated here (13). In contrast to our findings, Hardikar et al. reported suggestive evidence that the association between pre-diagnostic physical activity and subsequent colorectal cancer survival may be slightly stronger among those with tumors exhibiting high levels of microsatellite instability (mimicking the dMMR profile evaluated in this study); their results also indicated no difference in the magnitude of association by BRAF/KRAS somatic mutation status (13). Other analyses of post-diagnostic physical activity in relation to colorectal cancer outcomes have suggested that the benefits of physical activity may be greater among individuals with colorectal tumors that were negative for nuclear cadherin-associated protein β1 (CTNNB1) (40), positive for PTGS2 expression (41), and negative for expression of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) (42). Although CTNNB1, PTGS2, and IRS1 expression levels were not assayed in the N0147 study population, these prior studies highlight potential heterogeneity in the association between physical activity and cancer outcomes. Thus, although the broad-range benefits of physical activity are well established, it is plausible that the magnitude of that benefit may vary across the population of colon cancer patients.

The precise mechanisms underlying the association between physical activity and colon cancer outcomes are unknown; however, several factors are likely to contribute. In particular, physical activity has been suggested to lower insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) levels, and to elevate levels of IGF binding proteins, thereby reducing the potential impact of insulin and IGF on tumor growth (43, 44). Other studies have suggested that moderate physical activity is associated with greater T cell proliferation relative to in sedentary individuals (45–48), which may enable an enhanced immune response in colon cancer. Similarly, physical activity has been shown to reduce levels of chronic inflammation and serum prostaglandin levels (44, 49, 50); chronic overproduction of prostaglandins has previously been linked with cancer progression and metastasis (51, 52). Several additional mechanisms may plausibly underlie the observed associations with physical activity, both with respect to OS and disease-specific outcomes (44).

Results from the present analysis should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. In particular, information as to the timing of reported physical activity was non-specific: participants were asked about current physical activity patterns at a time shortly following colon cancer diagnosis, with no specification as to whether or not those patterns had recently changed in response to cancer symptoms, treatment, or life circumstances. Furthermore, because this physical activity information was not updated in follow-up interviews, we were not able to evaluate associations with continued patterns of physical activity after colon cancer diagnosis and treatment. We also lacked information on participation in specific activities (e.g., swimming, running) and the typical duration of activity sessions. As such, we were unable to estimate metabolic equivalent (MET) hours or other metrics of actual energy expenditure from physical activity, as previous studies have done (12–14, 35, 53–55). Given that the present study was conducted within a randomized clinical trial population, the generalizability of study findings to the broader population of all colon cancer patients is not fully known. Patients who enroll in randomized trials represent a more selected population and, thus, their personal characteristics, such as physical activity patterns, may differ from the general population of colon cancer patients. Residual confounding is also a potential concern; for example, we lacked detailed information on income and socioeconomic status, which are plausibly associated with both physical activity (56) and colon cancer outcomes (57). We also lacked information on other co-morbidities (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease) that could also have an impact on OS and also related to physical activity (58, 59). Also, although we were able to investigate heterogeneity by a number of participant and tumor attributes, it is plausible that the association between physical activity and colon cancer outcomes could vary according to attributes not captured by this study (e.g., NRAS mutation status). Last, although the overall included sample size was large, our numbers were limited within some strata defined by patient or tumor characteristics, which reduced our ability to identify heterogeneity in the association between physical activity and colon cancer survival.

Our study also has several important strengths, including the availability of information regarding multiple tumor markers, potential confounders, and standardized treatment data. Incorporating this information allowed us to better disentangle the association between physical activity and outcomes after colon cancer diagnosis. The associations we observed in this context are consistent with the existing literature (13, 36, 37, 53, 60–62), indicating a modest favorable association between physical activity and colon cancer outcomes.

Current guidelines suggest that cancer survivors, including colon cancer survivors, engage in 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week (63, 64). Although we did not collect information on duration of activity, and although physical activity information from our study cannot be clearly classified as reflecting strictly pre- or post-diagnostic patterns, our findings do support these guidelines – suggesting that higher physical activity around the time of colon cancer diagnosis is associated with more favorable colon cancer outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers K07CA172298; U10CA180821, U10CA180882 and UG1CA189823 (to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology); U10CA180790; U10CA180850; UG1CA189863; U10CA180820 (ECOG-ACRIN); U10CA180863 and CCSRI #021039 and 704970 (CCTG); U10CA180835 and U10CA180888 (SWOG). The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures: None.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00079274

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2017–2019. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dienstmann R, Mason MJ, Sinicrope FA, Phipps AI, Tejpar S, Nesbakken A, et al. Prediction of overall survival in stage II and III colon cancer beyond TNM system: a retrospective, pooled biomarker study. Ann Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guastadisegni C, Colafranceschi M, Ottini L, Dogliotti E. Microsatellite instability as a marker of prognosis and response to therapy: A meta-analysis of colorectal cancer survival data. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2788–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, Burnett-Hartman AN, Coghill AE, Passarelli MN, et al. BRAF mutation status and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis according to patient and tumor characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1792–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinicrope FA, Shi Q, Smyrk TC, Thibodeau SN, Dienstmann R, Guinney J, et al. Molecular markers identify subtypes of stage III colon cancer associated with patient outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:88–99. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogino S, Shima K, Meyerhardt JA, McCleary NJ, Ng K, Hollis D, et al. Predictive and prognostic roles of BRAF mutation in stage III colon cancer: results from intergroup trial CALGB 89803. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:890–900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Yan P, Fiocca R, Klingbiel D, et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:466–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phipps AI, Baron J, Newcomb PA. Prediagnostic smoking history, alcohol consumption, and colorectal cancer survival: The Seattle Colon Cancer Family Registry. Cancer. 2011;117:4948–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phipps AI, Shi Q, Newcomb PA, Nelson GD, Sargent DJ, Alberts SR, et al. Associations Between Cigarette Smoking Status and Colon Cancer Prognosis Among Participants in North Central Cancer Treatment Group Phase III Trial N0147. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2016–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phipps AI, Shi Q, Limburg PJ, Nelson GD, Sargent DJ, Sinicrope FA, et al. Alcohol consumption and colon cancer prognosis among participants in north central cancer treatment group phase III trial N0147. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:986–95. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phipps AI, Robinson JR, Campbell PT, Win AK, Figueiredo JC, Lindor NM, et al. Prediagnostic alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer survival: The Colon Cancer Family Registry. Cancer. 2017;123:1035–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuiper JG, Phipps AI, Neuhouser ML, Chlebowski RT, Thomson CA, Irwin ML, et al. Recreational physical activity, body mass index, and survival in women with colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1939–48. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardikar S, Newcomb PA, Campbell PT, Win AK, Lindor NM, Buchanan DD, et al. Prediagnostic Physical Activity and Colorectal Cancer Survival: Overall and Stratified by Tumor Characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1130–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu W, Guo F, Ye J, Li Y, Shi D, Fang D, et al. Pre- and post-diagnosis physical activity is associated with survival benefits of colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samad AK, Taylor RS, Marshall T, Chapman MA. A meta-analysis of the association of physical activity with reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2005;7:204–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norat T, Chan D, Lau R, Aune D, Vieira R, Greenwood D, et al. The associations between food, nutrition, and physical activity and the risk of colorectal cancer. London: Imperial College London; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaaks R, Lukanova A. Energy balance and cancer: the role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001;60:91–106. doi: 10.1079/pns200070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giovannucci E. Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and colon cancer: a review of the evidence. J Nutr. 2001;131:3109S–20S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3109S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koenuma M, Yamori T, Tsuruo T. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 stimulate proliferation of metastatic variants of colon carcinoma 26. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1989;80:51–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1989.tb02244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoen RE, Tangen CM, Kuller LH, Burke GL, Cushman M, Tracy RP, et al. Increased blood glucose and insulin, body size, and incident colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1147–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo YS, Narayan S, Yallampalli C, Singh P. Characterization of insulinlike growth factor I receptors in human colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1101–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma J, Pollak MN, Giovannucci E, Chan JM, Tao Y, Hennekens CH, et al. Prospective study of colorectal cancer risk in men and plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-binding protein-3. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:620–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.7.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manousos O, Souglakos J, Bosetti C, Tzonou A, Chatzidakis V, Trichopoulos D, et al. IGF-I and IGF-II in relation to colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:15–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990924)83:1<15::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Nair S, Mahoney MR, Mooney M, Thibodeau SN, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1383–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Leontovich O, Goldberg RM, Cunningham JM, Sargent DJ, et al. Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing in phenotyping colorectal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1043–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domingo E, Laiho P, Ollikainen M, Pinto M, Wang L, French AJ, et al. BRAF screening as a low-cost effective strategy for simplifying HNPCC genetic testing. Journal of medical genetics. 2004;41:664–8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman & Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J Royal Stat Soc Series B (Methodological) 1972;34:187–220s. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Des Guetz G, Uzzan B, Bouillet T, Nicolas P, Chouahnia K, Zelek L, et al. Impact of physical activity on cancer-specific and overall survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:340851. doi: 10.1155/2013/340851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Je Y, Jeon JY, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA. Association between physical activity and mortality in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1905–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Association between physical activity and mortality among breast cancer and colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1293–311. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyerhardt JA, Heseltine D, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, et al. Impact of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3535–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haydon AM, Macinnis RJ, English DR, Giles GG. Effect of physical activity and body size on survival after diagnosis with colorectal cancer. Gut. 2006;55:62–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.068189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell PT, Patel AV, Newton CC, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM. Associations of recreational physical activity and leisure time spent sitting with colorectal cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:876–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walter V, Jansen L, Knebel P, Chang-Claude J, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Physical activity and survival of colorectal cancer patients: Population-based study from Germany. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:1985–97. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pelser C, Arem H, Pfeiffer RM, Elena JW, Alfano CM, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Prediagnostic lifestyle factors and survival after colon and rectal cancer diagnosis in the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer. 2014;120:1540–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Meyerhardt JA, Shima K, Nosho K, et al. Association of CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) alterations, body mass index, and physical activity with survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Jama. 2011;305:1685–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Imamura Y, Kuchiba A, Liao X, Qian ZR, et al. Physical activity, tumor PTGS2 expression, and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1142–52. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanyuda A, Kim SA, Martinez-Fernandez A, Qian ZR, Yamauchi M, Nishihara R, et al. Survival Benefit of Exercise Differs by Tumor IRS1 Expression Status in Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:908–17. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4967-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandhu MS, Dunger DB, Giovannucci EL. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), IGF binding proteins, their biologic interactions, and colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:972–80. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.13.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas RJ, Kenfield SA, Jimenez A. Exercise-induced biochemical changes and their potential influence on cancer: a scientific review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:640–4. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simpson RJ, Lowder TW, Spielmann G, Bigley AB, LaVoy EC, Kunz H. Exercise and the aging immune system. Ageing research reviews. 2012;11:404–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bigley AB, Spielmann G, LaVoy EC, Simpson RJ. Can exercise-related improvements in immunity influence cancer prevention and prognosis in the elderly? Maturitas. 2013;76:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nieman DC, Henson DA, Gusewitch G, Warren BJ, Dotson RC, Butterworth DE, et al. Physical activity and immune function in elderly women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:823–31. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199307000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shinkai S, Kohno H, Kimura K, Komura T, Asai H, Inai R, et al. Physical activity and immune senescence in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1516–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson SD, Pojer R, Smith ID, Temple D. Exercise-related changes in plasma levels of 15-keto-13,14-dihydro-prostaglandin F2alpha and noradrenaline in asthmatic and normal subjects. Scand J Respir Dis. 1976;57:41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fairey AS, Courneya KS, Field CJ, Mackey JR. Physical exercise and immune system function in cancer survivors: a comprehensive review and future directions. Cancer. 2002;94:539–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu XH, Yao S, Kirschenbaum A, Levine AC. NS398, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, induces apoptosis and down-regulates bcl-2 expression in LNCaP cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hsu AL, Ching TT, Wang DS, Song X, Rangnekar VM, Chen CS. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib induces apoptosis by blocking Akt activation in human prostate cancer cells independently of Bcl-2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11397–403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, Chan AT, Chan JA, Colditz GA, et al. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3527–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Ogino S, Kirkner GJ, Chan AT, Willett W, et al. Physical activity and male colorectal cancer survival. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2102–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meyerhardt JA, Ogino S, Kirkner GJ, Chan AT, Wolpin B, Ng K, et al. Interaction of molecular markers and physical activity on mortality in patients with colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5931–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. Socioeconomic status differences in recreational physical activity levels and real and perceived access to a supportive physical environment. Prev Med. 2002;35:601–11. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manser CN, Bauerfeind P. Impact of socioeconomic status on incidence, mortality, and survival of colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:42–60 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aune D, Norat T, Leitzmann M, Tonstad S, Vatten LJ. Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:529–42. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berlin JA, Colditz GA. A meta-analysis of physical activity in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:612–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boyle T, Fritschi L, Platell C, Heyworth J. Lifestyle factors associated with survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:814–22. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arem H, Pfeiffer RM, Engels EA, Alfano CM, Hollenbeck A, Park Y, et al. Pre- and postdiagnosis physical activity, television viewing, and mortality among patients with colorectal cancer in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:180–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Romaguera D, Ward H, Wark PA, Vergnaud AC, Peeters PH, van Gils CH, et al. Pre-diagnostic concordance with the WCRF/AICR guidelines and survival in European colorectal cancer patients: a cohort study. BMC Med. 2015;13:107. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–26. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:243–74. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]