Abstract

Genetic diversity is essential for survival and adaptation of high altitude plants such as those of Tanacetum genus, which are constantly exposed to environmental stress. We collected flowering shoots of ten accessions of Tanacetum gracile Hook.f. & Thomson (Asteraceae) (Tg 1–Tg 10), from different regions of cold desert of Western Himalaya. Chemical profile of the constituents, as inferred from GC–MS, exhibited considerable variability. Percentage yield of essential oil ranged from 0.2 to 0.75% (dry-weight basis) amongst different accessions. Tg 1 and Tg 6 were found to produce high yields of camphor (46%) and lavandulol (41%), respectively. Alpha-phellendrene, alpha-bisabool, p-cymene and chamazulene were the main oil components in other accessions. Genetic variability among the accessions was studied using RAPD markers as well as by sequencing and analyzing nuclear 18S rDNA, and plastid rbcL and matK loci. The polymorphic information content (PIC) of RAPD markers ranged from 0.18 to 0.5 and the analysis clustered the accessions into two major clades. The present study emphasized the importance of survey, collection, and conservation of naturally existing chemotypes of medicinal and aromatic plants, considering their potential use in aroma and pharmaceutical industry.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1299-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Essential oil, GC–MS, ITS, MatK, RAPD, RbcL

Introduction

Plants are known to accumulate diverse and commercially important phytochemicals. Many such compounds are used as flavors, fragrances and insect repellents, while some are also used as dyes and drugs (Gandhi et al. 2015). Aromatic plants produce odorous compounds that are volatile at room temperature, most of which are essential oils useful in the flavor and fragrance industry. Essential oils are known to accumulate in secretary cells or cavities in plant organs such as leaves, buds, seeds, roots, flowers, stems, fruits, etc. (Wagner 1991; Sangwan et al. 2001; Ahmadi et al. 2002; Ciccarelli et al. 2008). Several essential oil bearing plants belong to the plant families Lamiaceae, Umbelliferae, and Asteraceae (Franz and Novak 2015). Apart from uses in perfumery and culinary, essential oil components have been shown to possess antimicrobial, analgesic, stimulant, sedative, or hypotensive activities (Christaki et al. 2012; Djilani and Dicko 2012; Rozza and Pellizzon 2013). Aromatherapy, a complementary system of medicine, uses essential oils for ameliorating conditions such as anxiety, depression, hypertension and nicotine withdrawal (Kamble et al. 2014). Essential oils from several aromatic plants growing in Western Himalaya have been assessed for their composition. Linalool and linalyl acetate were found to be the main components in essential oil of Skimmia laureola Franch. (Rutaceae), while sabinene was the main component in Juniperus macropoda Boiss. (Cupressaceae) (Stappen et al. 2015a). Similarly, chemical profiling of essential oils from two Lamiaceae family members from Western Himalaya showed that pinocarvone, cis-pinocamphone and β-pinene were the main components of Hyssopus officinalis L. oil, while citronellol was the main component in oil of Dracocephalum heterophyllum Benth. (Stappen et al. 2015b) Populations of Bunium persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. (Apiaceae) collected from North-Western Himalaya exhibited significant variation in essential oil content and composition, which was correlated to genetic diversity assessed using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers (Chahota et al. 2017). RAPD is a simple and inexpensive molecular technique used for assessment of genetic relatedness/variability amongst individuals belonging to a wide range of taxonomic levels. It involves the use of decamer oligonucleotides of random sequence as PCR primers that anneal at several loci in the genome and wherever feasible, result in amplicons that are resolved through agarose gel electrophoresis. Similarity banding pattern is scored for calculation of genetic relatedness (Bardakci 2001; Jones et al. 2009). The Trade of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs), in India as well as worldwide, has continuously increased in the past decade (Chauhan et al. 2013). The Himalayas are spread in about 2400 km, ranging in altitude from 200 to 8000 m, which supports a large diversity of flora and fauna (Samant et al. 2007). However, blatant exploitation of natural resources and collection of MAPs from the wild is a continuous threat to biodiversity (Chauhan et al. 2013; Mahajan et al. 2015b). The Himalayan region has shown a consistent warming trend during the past 100 years. This has led to shifting of certain temperature sensitive species to higher altitudes, as well as early flowering and fruiting in plants such as Rhododendron sp. (Ratha et al. 2012; Das and Chattopadhyay 2013).

Tanacetum gracile Hook.f. & Thomson, an aromatic perennial herb of family Asteraceae, is native to higher altitudes of north-Western Himalaya between 2800 and 3600 m above mean sea level (Polunin and Stainton 1984; Kitchlu et al. 2006). T. gracile plant is erect, usually 20–100 cm tall with a thick woody rootstock, several stems arise from the woody base (Kachroo and Sapru 1977). The stem is branched at the base, gray pubescent and varies in size depending on height of the plant. The leaves are alternate, sparsely arranged on the stem, having cut linear blunt segments; leaf segment 2–3 cm long, 1.5–2 cm broad, petiolate to subsessile, irregularly pinnatifid with entire margin. Inflorescence is terminal with clusters of tiny (0.2–0.3 cm across) yellow flower heads (Polunin and Stainton 1984; Gilbert 2011). Inflorescence has marginal and disk florets; the marginal florets are female with narrowly tubular corolla, while disk florets are bisexual and with obtuse anthers (Kachroo and Sapru 1977). The involucral bracts are papery, hairless, and broadly oblong. The fruit is ‘achene’, which is obovoid, angular, 0.1–0.2 cm across. Several species of Tanacetum have been explored for their chemistry and pharmacological properties (Tétényi et al. 1975; Nano et al. 1979; Abad et al. 1994; Beauchamp et al. 2001). Sesquiterpenoids, sesquiterpene lactones and monoterpenes are the main phytochemical constituents of this genus (Abad et al. 1995). We have earlier reported T. gracile as a new source of lavandulol (Kitchlu et al. 2006) and demonstrated that essential oil extracted from T. gracile induces mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in HL-60 cancer cell line (Verma et al. 2008). In another study, essential oil composition of related species T. gracile and T. nubigenum Wall. ex DC., collected from Alpine Himalaya, was compared (Lohani et al. 2012). However, a detailed study comparing the chemical and genetic variability in naturally existing populations of T. gracile was lacking. Here, we report the composition of essential oil extracted from accessions of T. gracile, collected from different regions of cold desert of Western Himalaya. Genetic diversity amongst these accessions was assessed using RAPD markers. We have also sequenced and analyzed molecular markers like the plastid maturase K (matK) & ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase large subunit (rbcL) genes and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of nuclear 18S rDNA, which are also widely used for studying inter- and intra-specific evolutionary distances (Kazi et al. 2013).

Materials and methods

Collection of plant material

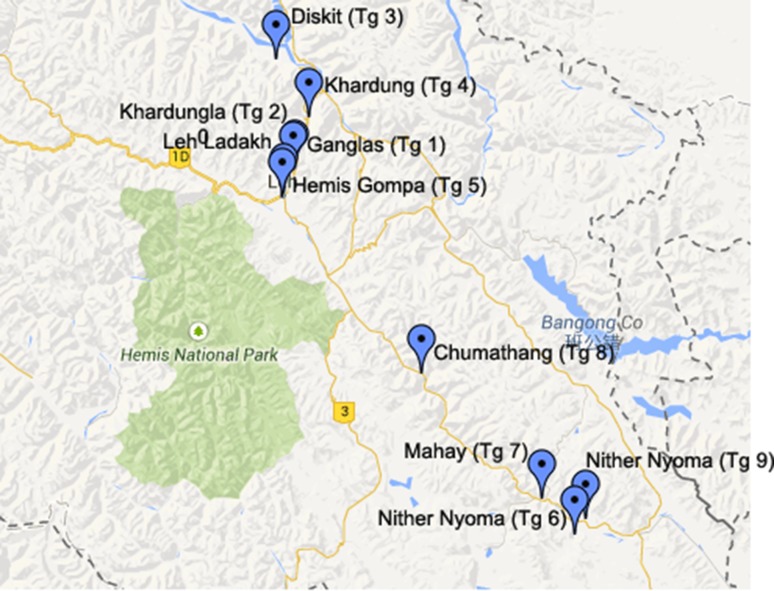

T. gracile accessions (Tg 1–Tg 10) were collected in flowering stage, from various locations (77° 33′ 22.36″E, 34° 32′ 54.6″N to 78° 38′ 54.2″E, 33° 12′ 21.3″N) in north-western Himalaya (Fig. 1; Table 1). The accessions Tg 1–Tg 6 were collected in July, 2010; Tg 7 and Tg 8 were collected in July, 2012; Tg 9 and Tg 10 were collected in July, 2013. Plants were identified and authenticated by conventional taxonomic methods based on morphological characters of plant, leaves, inflorescence, etc. Dried aerial parts were submitted to the institutional crude drug repository (CSIR-IIIM) and accession numbers obtained were: 4001–4010 for T. gracile accessions (Tg 1–Tg 10), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Collection of accessions of T. gracile from cold desert of Western Himalaya

Table 1.

Locations and total essential oil content of different accessions of T. gracile collected from various regions of Western Himalaya

| Sample code | Place of collection | Altitude (metres) | Longitude E | Latitude N | Essential oil content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg 1 | Ganglas | 4306 | 77° 37′ 34.7″ | 34° 13′ 40.8″ | 0.5 |

| Tg 2 | Khardungla | 4396 | 77° 37′ 03.1″ | 34° 13′ 32.5″ | 0.5 |

| Tg 3 | Diskit | 3850 | 77° 33′ 22.36″ | 34°32′ 54.6″ | 0.5 |

| Tg 4 | Khardung | 4070 | 77° 40′ 23.3″ | 34° 22′ 55.8″ | 0.4 |

| Tg 5 | Hemis Gompa | 3640 | 77° 34′ 51.0″ | 34° 09′ 01.0″ | 0.3 |

| Tg 6 | Nither Nyoma | 4200 | 78° 38′ 54.2″ | 33° 12′ 21.3″ | 0.3 |

| Tg 7 | Mahay | 4152 | 78° 29′ 40.1″ | 33° 15′ 56.3″ | 0.35 |

| Tg 8 | Chumathang | 3697 | 78° 04′ 14.8″ | 33° 37′ 55.2″ | 0.34 |

| Tg 9 | Nither Nyoma | 4216 | 78° 36′ 27.2″ | 33° 09′ 30.1″ | 0.26 |

| Tg 10 | Leh Ladakh | 3452 | 77° 35′ 00.9″ | 34° 09′ 37.8″ | 0.75 |

Extraction of essential oil and instrumentation

Essential oil was extracted from shade dried flowering shoots of different accessions of T. gracile in a clevenger-type apparatus. Dried herb (500 mg) was hydro-distilled for 4–5 h for extraction of essential oil. The extracted essential oil was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate and stored in dark at − 20 °C until further analysis. Analysis of components present in the essential oil samples was carried out by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC–MS). The spectra were recorded on a varian-4000 model fitted with fused silica column type WCOT (30 m × 0.32 mm × 1 µm) coated with CP-Sil-8 CB/MS. GC was conducted at 50–250 °C with programming rate of 3°C/min, using helium as carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 ml/min and injector temperature at 280 °C. The GC column was coupled directly to an ion trap mass spectrometer using EI mode. Mass spectra were recorded from m/z 40 to 500. Percentage composition of oils was ascertained from GC peak areas. Retention indices were determined relative to C7–C30 hydrocarbon standard mixture. Identification of the essential oil components was carried out by comparing the mass spectra and retention indices with NIST library and available literature. Similar protocol has been used earlier by us (Mahajan et al. 2015a) and others (Dar et al. 2011; Koli et al. 2018), for analysis and quantification of essential oil components.

Rapid amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD)

Total genomic DNA was extracted by CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle 1987). Polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were performed in a thermal cycler (Mastercycler™ pro S, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) in total volume of 20 µl reaction mixture containing 2 µl buffer (10X; with MgCl2), 2 µl each primer (5 µM) (Refer Table 2 for primer sequences), 2 µl dNTPs (2 mM), 1 unit of Taq DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Inc., England, UK) and about 20–30 ng template DNA. Seven RAPD primers were used for the analysis. Thermal cycler was programmed with following parameters: 95 °C- 5 min, followed by 5 cycles of 95 °C- 30 s, annealing 24 °C- 1 min & 72 °C- 2 min. This was followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C- 30 s, annealing 26 °C- 1 min & 72 °C- 2 min and final extension 72 °C- 10 min, followed by holding at 4 °C. PCR products were run on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized using a gel documentation system (Syngene, CA, USA).

Table 2.

Nucleotide sequence of primers

| S. no. | Primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | matK-1RKIM-f | 5′-ACCCAGTCCATCTGGAAATCTTGGTTC-3′ |

| 2 | matK-3FKIM-r | 5′-CGTACAGTACTTTTGTGTTTACGAG-3′ |

| 3 | rbcLa-F | 5′-ATGTCACCACAAACAGAGACTAAAGC-3′ |

| 4 | rbcLa-R | 5′- GTAAAATCAAGTCCACCGCG − 3′ |

| 7 | ITS2-S2F | 5′- ATGCGATACTTGGTGTGAAT − 3′ |

| 8 | ITS4 | 5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′ |

| 9 | RAPD-7 | 5′-ACATCGCCCA-3′ |

| 10 | RAPD-12 | 5′-ACGGCAACCT-3′ |

| 11 | RAPD-17 | 5′-AGGCGGGAAC-3′ |

| 12 | RAPD-18 | 5′-AGGCTGTGTC-3′ |

| 13 | RAPD-19 | 5′-AGGTGACCGT-3′ |

| 14 | RAPD-21 | 5′-CACGAACCTC-3′ |

| 15 | RAPD-24 | 5′-CCAGCCGAAC-3′ |

Statistical evaluations

RAPD bands were scored as discrete variables; the presence of a DNA amplification band was scored as 1 and absence of a band of same size in a different accession was scored as 0 (binary data). Genetic similarity was calculated between two accessions based on Dice coefficient (Nei and Li 1979) of similarity; GS(ij) = 2a/(2a + b + c), where GS(ij) is the genetic similarity between two accessions ‘i’ and ‘j’, ‘a’ is the number of polymorphic bands that are shared between ‘i’ and ‘j’, ‘b’ is the number of bands present in ‘i’ and absent in ‘j’ and ‘c’ is the number of bands absent in ‘i’ and present in ‘j’. Binary data was used to generate a similarity matrix using the Dice coefficient in ‘SimQual’ module of NTSYSpc ver 2.2 (http://www.exetersoftware.com/cat/ntsyspc/ntsyspc.html) and further clustered in ‘SAHN’ subroutine using UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic mean) method for plotting dendrogram.

Polymorphic information content of markers was calculated using the Roldàn-Ruiz formula (Roldán-Ruiz et al. 2000); PICi = 2fi (1-fi), where fi is the frequency of amplified band and (1-fi) is the frequency of band absent (null allele) of marker ‘i’.

Phylogenetic relationships among different accessions based on their individual essential oil components were assessed by plotting a double dendrogram (hierarchical clustering), as described earlier (Mahajan et al. 2015a). Computations were made using NCSS 2007 (Hintze 2007) version 07.1.14. Distances were calculated using Euclidean method and clustering was done based on group average (Unweighted Pair Group Method).

Sequence based diversity analysis

Specific portions from matK, rbcL genes and ITS region of 18S rDNA were amplified and sequenced for sequence based phylogenetic analysis. DNA isolation and PCRs were carried out as described above for RAPD analysis, with the exception that here the concentration of primers used was 2.5 µM (Refer Table 2 for primer sequences) and thermal cycling conditions were set as: 5 min at 95 °C, 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, 1 min at 72 °C, and a final extension of 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were loaded in agarose gel (1%), bands were excised and eluted using gel extraction kit (MinElute, QIAGEN, Limburg, The Netherlands) and sequenced by sanger dideoxy method in an automated DNA sequencer (ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer; Applied Biosystems, Inc., CA, USA). For each locus (matK, rbcL and ITS), sequences from all the T. gracile accessions were aligned using ClustalW algorithm and phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA5 software version 5.2 (Saitou and Nei 1987).

Results and discussion

Assessment of essential oil content

The essential oil content (dry-weight basis) of different accessions of T. gracile ranged from 0.2 to 0.75% (Table 1). Percentages of individual components in essential oil are listed in Supplementary File 1. Tg 1 accession of T. gracile was found to be rich in camphor (46.11%), followed by Tg 7 (14.2%), while six other accessions showed presence of camphor in minor quantities. Lavandulol was detected in nine accessions of T. gracile and formed the major constituent in Tg 6 accession (41.6%). Terpeniol, alpha-pinene, sabinene, eucalyptol, p-cymene, γ-terpinene and terpinolene were present in all the ten accessions under study. Alpha-phellendrene was observed in nine accessions and constituted the common major component in Tg 4 (21.01%), Tg 8 (33.23%), Tg 9 (39.68%) and Tg 10 (36.07%), while p-cymene was present in significant quantities in Tg 5 (20.94%) and Tg 4 (15.80%). α-bisabolol and chamazulene accounted for more than 30% of the oil in Tg 2, Tg 3 and Tg 7.

It was also intriguing to observe the evolutionary divergence among these chemotypes based on their individual essential oil components. Therefore, a phylogenetic analysis was carried out by plotting a double dendrogram (Fig. 2) showing inter-relationships amongst different accessions of T. gracile based on differences and/or similarities in their essential oil composition (X axis of dendrogram). The dendrogram also depicts the propensity of essential components being coproduced (Y-axis of dendrogram). Tg 7 and Tg 8 were found to be closely related, while Tg 5 and Tg 6 appeared to be distantly related on the basis of their essential oil composition.

Fig. 2.

Diversity analysis of different accessions of T. gracile based on essential oil content

In India, twelve species of Tanacetum genus have been reported from the Himalaya (Lohani et al. 2012). Chemical variability, amongst Tanacetum species from the Himalaya, has been reported in various studies (Beauchamp et al. 2001; Chanotiya et al. 2005; Mathela et al. 2008; Verma et al. 2008). Furthermore, chemotypes of T. vulgare exhibiting variability in essential oil composition were also reported from north-eastern parts of the Netherlands (Hendriks et al. 2011). Accessions of T. gracile were collected from cold desert region of Western Himalayas and identified through conventional taxonomic methods. Our analysis revealed considerable variability amongst the collected accessions of T. gracile, not only in the total essential oil content (dry-weight basis) but also in the quantities of individual components. One of the accessions (Tg 1) was found to be rich in camphor (46.11%). Camphor is a terpenoid that is readily absorbed through skin and produces a cooling effect comparable to menthol. It is known to have anesthetic and antimicrobial properties and finds uses in balms and vapor–steam products (Committee on Drugs 1994; Magiatis et al. 2002). Camphor has been reported in high quantities in several other species of Tanacetum, such as T. chiliophyllum (Fisch. & C.A. Mey. ex DC.) Sch. Bip. (17%) and T. haradjani (Rech.f.) Grierson (16%) (Baser et al. 2001), T. vulgare L. (7.2–18.5%) (Keskitalo et al. 2001), T. parthenium Schultz Bip. (18.94%) (Mohsenzadeh et al. 2011), T. pinnatum Boiss. (23.2%) (Esmaeili et al. 2009) and T. balsamita L. (7.5%) (Bagci et al. 2008). Another accession (Tg 6) accumulated lavandulol in a high percentage (41.6%). Lavandulol is a monoterpenol having characteristic floral odor and has commercial importance in cosmetic industry (McCullough et al. 1991). Earlier studies have revealed presence of lavandulol in T. fruticulosum Ledeb. and T. paradoxum Bornm. collected from Iran, with lavandulol content of 10.8 and 15.9%, respectively (Weyerstahl et al. 1999; Habibi et al. 2007). We have also earlier reported T. gracile from alpine Western Himalaya region, Ganglas, containing high amount (21.5%) of lavandulol (Kitchlu et al. 2006). It is noteworthy that T. gracile accession collected from Ganglas (Tg 1), in this study, was camphor rich (46.11%) and contained lavandulol in minute amounts (1.23%), while collection made from Nither Nyoma (Tg 6) appears to be the richest source of lavandulol, to date (41.6%). Interestingly, biosynthesis of camphor and lavandulol involves two inter-convertible precursors: dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), generated from the mevalonate and non-mevalonate pathways (Hunter 2007). IPP and DMAPP, via a series of chemical reactions, lead to the synthesis of camphor (Croteau and Shaskus 1985) in T. vulgare, while DMAPP is involved in lavandulol production (Demissie et al. 2013). Therefore, partitioning of the common precursor to the divergent pathways generating camphor and lavandulol may be responsible for the observed chemical profile of camphor rich Tg 1 accession (46.1% camphor, with lower lavandulol concentration of 1.23%) and lavandulol rich Tg 6 accession (41.6% lavandulol, with lower camphor concentration of 3.25%).

Diversity analysis

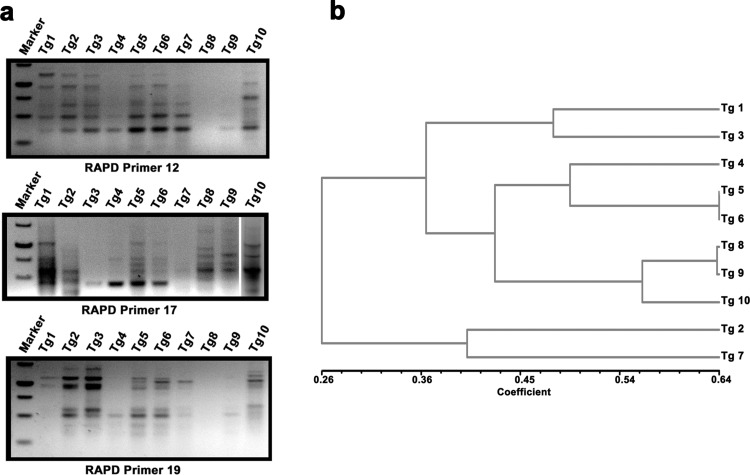

RAPD was used for analyzing intra-specific genetic diversity amongst accessions of T. gracile collected from different regions of cold desert of Western Himalaya. PCR amplification profile of T. gracile accessions using three RAPD markers is shown in Fig. 3a. RAPD analysis revealed that T. gracile accessions used in the study were genetically distinct. A total of 71 bands were scored and the polymorphic information content (PIC) of RAPD markers used in the study ranged from 0.18 to 0.5. Genetic similarity amongst different accessions of T. gracile, estimated using Dice similarity index, ranged from 0.170 to 0.636. Complete linkage clustering resolved the accessions in two major clades (Fig. 3b). Least genetic distance was observed between Tg 5 and Tg 6, showing that these accessions are closely related to each other.

Fig. 3.

RAPD profile of T. gracile accessions

Variability in essential oil composition suggested an underlying genetic diversity in the collected accessions. In outcrossing species, such as those of Tanacetum genus, genetic diversity is essential for long term survival (Hamrick and Godt 1996), as this enables the species to acclimatize to the anthropogenic as well as environmental selective pressures (Yamagishi et al. 2009). RAPD has earlier been used to study genetic diversity in Tanacetum vulgare (Keskitalo et al. 1998) as well as for correlation of genetic diversity with essential oil variability in Ocimum basilicum (Giachino et al. 2014), Ocimum gratissimum (Vieira et al. 2001), Ephedra species (Ehtesham-Gharaee et al. 2017), etc. Vieira et al (2001) examined five accessions of O. gratissimum with varying content of thymol, eugenol and geraniol. They scored 32 bands in RAPD analysis and showed that the genetic similarity amongst O. gratissimum accessions ranged from 0.200 to 0.667. Our RAPD study also showed genetic diversity in the collected accessions of T. gracile. Phylogram based on chemical markers clustered the accessions differently as compared to that made from RAPD marker data. In the analysis of Vieira et al (2001) also, it was observed that the eugenol rich accessions were not as homogenous, at genetic level, as the thymol rich accessions of O. gratissimum. Use of more scorable RAPD markers may increase the correlation between the phylograms based on chemical and RAPD markers. However, it is noteworthy that apart from genetic variability, altitude and other environmental cues may also play crucial roles in determining the chemical profile.

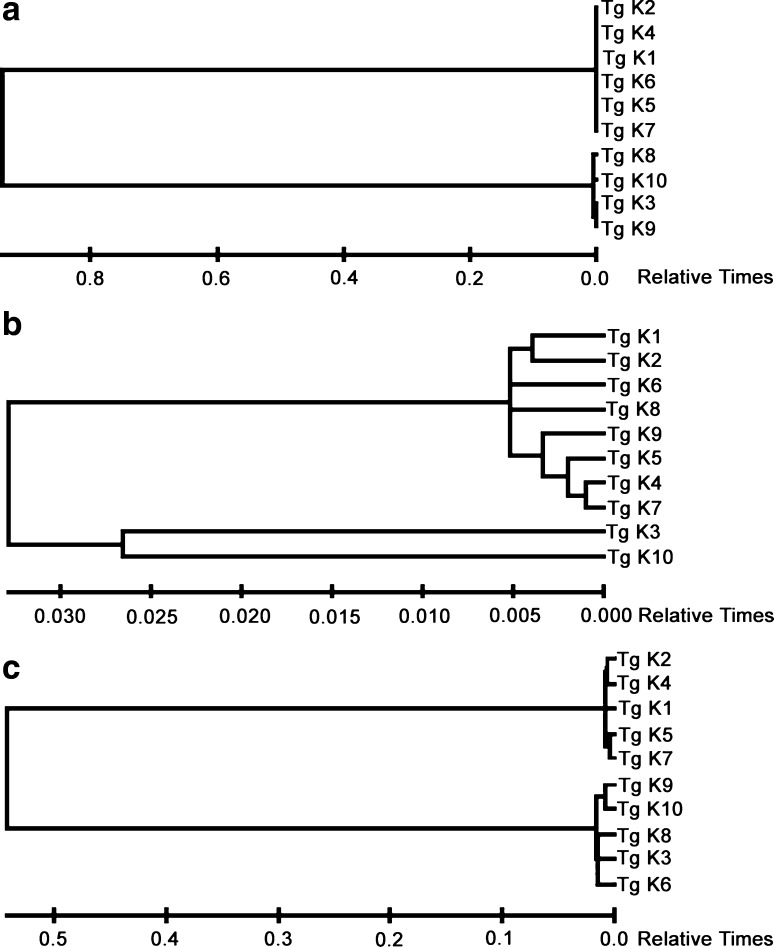

Plastid and nuclear DNA sequences have also been extensively used for studying inter- and intra-specific phylogenetic relationships (Kocyan et al. 2004; Kazi et al. 2013). In this study, we have sequenced and analyzed two plastid markers- matK, rbcL and one nuclear marker- the ITS region of 18S rDNA (see Supplementary File 2 for sequences) for determining evolutionary distances amongst accessions of T. gracile. As expected, phylogenetic analysis revealed that accessions under study were closely related to each other (Fig. 4). All the markers clustered Tg 1, Tg 2, Tg 4, Tg 5 and Tg 7 together suggesting greater degree of relatedness among these accessions. These markers are also frequently used for DNA Barcoding of land plants (Hollingsworth et al. 2011). DNA Barcoding is a simple, molecular, taxonomic method that relies on sequencing specific DNA markers that show very little variability amongst members of the same species, while significant divergence is observed amongst members of different species. It is useful in identification of plants or plant specimens at any developmental stage and using any plant part, in any form (live, dry or powdered) (Kress 2017). All the sequence data that was generated in our study is available in supplementary file 2. This data may be useful in species identification.

Fig. 4.

Sequence based diversity analysis of different accessions of T. gracile

Conclusion

Essential oil composition from accessions of T. gracile collected from different locations of Western Himalaya showed considerable variation. DNA markers revealed that these accessions were indeed genetically distinct. Certain accessions were found to be rich in commercially important essential oil constituents such as camphor and lavandulol. Apart from genetic variability, other parameters such as time of sample collection and the altitude may also impact the chemical composition of essential oils. The information generated with respect to the chemical diversity observed in the highly valued constituents like camphor and lavandulol in ten accessions of T. gracile could be of utmost importance for future breeding programmes and conservation activities for this species. The sequence data generated for DNA Barcoding markers will be useful for molecular identification of plant samples and may be helpful in forensic analysis and combating illegal trade of T. gracile plants. This study attempts to draw attention to the significance of survey, collection and conservation of naturally occurring chemotypes of important medicinal and aromatic plants.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

VM and RC were supported by CSIR-Senior/Junior research fellowships, respectively. SGG acknowledges the financial support for this work from CSIR 12th FYP projects ‘BioprosPR’ (BSC0106) of Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR).

Author contributions

VM carried out genetic marker studies, wrote the manuscript and prepared figures. RC helped VM in preparation of manuscript and figures. SK and SK collected T. gracile accessions and carried out extraction of essential oil. BS performed taxonomical identification and authentication of plant. KB performed GC-MS of the essential oils. SGG designed the study and edited the manuscript and figures. YSB and SK provided critical inputs for the study as well as during preparation of manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1299-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Abad MJ, Bermejo P, Valverde S, Villar A. Anti-inflammatory activity of hydroxyachillin, a sesquiterpene lactone from Tanacetum microphyllum. Planta Med. 1994;60:228–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad MJ, Bermejo P, Villar A. An approach to the genus Tanacetum L. (Compositae): phytochemical and pharmacological review. Phytother Res. 1995;9:79–92. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2650090202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi L, Mirza M, Shahmir F. The volatile constituents of Artemisia marschaliana sprengel and its secretory elements. Flavour Fragr J. 2002;17:141–143. doi: 10.1002/ffj.1055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagci E, Kursat M, Kocak A, Gur S. Composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of Tanacetum balsamita L. subsp. balsamita and T. chiliophyllum (Fisch. et Mey.) Schultz Bip. var. chiliophyllum (Asteraceae) from Turkey. J Essent Oil Bear Pl. 2008;11:476–484. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2008.10643656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bardakci F. Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers. Turk J Biol. 2001;25:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Baser KHC, Demirci B, Tabanca N, Ozek T, Goren N. Composition of the essential oils of Tanacetum armenum (DC.) Schultz Bip., T. balsamita L. T. chiliophyllum (Fisch. & Mey) Schultz Bip. var. chiliophyllum and T. haradjani (Rech. fil.) Grierson and the enantiomeric distribution of camphor and carvone. Flavour Fragr J. 2001;16:195–200. doi: 10.1002/ffj.977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp P, Dev V, Kashyap T, Melkani A, Mathela C, Bottini AT. Composition of the essential oil of Tanacetum nubigenum Wallich ex DC. J Essent Oil Res. 2001;13:319–323. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2001.9712223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chahota RK, Sharma V, Ghani M, Sharma TR, Rana JC, Sharma SK. Genetic and phytochemical diversity analysis in Bunium persicum populations of north-western Himalaya. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2017;23:429–441. doi: 10.1007/s12298-017-0428-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanotiya CS, Sammal SS, Mathela CS. Composition of a new chemotype of Tanacetum nubigenum. Indian J Chem. 2005;44(B):1922–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan RS, Nautiyal BP, Nautiyal MC. Trade of threatened Himalayan medicinal and aromatic Plants-socioeconomy, management and conservation issues in Garhwal Himalaya, India. Global J Pathol Microbiol. 2013;13:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Christaki E, Bonos E, Giannenas I, Florou-Paneri P. Aromatic plants as a source of bioactive compounds. Agriculture. 2012;2:228–243. doi: 10.3390/agriculture2030228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli D, Garbari F, Pagni AM. The flower of Myrtus communis (Myrtaceae): secretory structures, unicellular papillae, and their ecological role. FLORA. 2008;203:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2007.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on drugs Camphor revisited: focus on toxicity. Pediatrics. 1994;94:127–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau R, Shaskus J. Biosynthesis of monoterpenes: demonstration of a geranyl pyrophosphate:(-)-bornyl pyrophosphate cyclase in soluble enzyme preparations from tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;236:535–43. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar MY, Shah WA, Rather MA, Qurishi Y, Hamid A, Qurishi MA. Chemical composition, in vitro cytotoxic and antioxidant activities of the essential oil and major constituents of Cymbopogon jawarancusa (Kashmir) Food Chem. 2011;129:1606–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das N, Chattopadhyay KK. Change in climate—a threat to Eastern Himalayan biodiversity. JTBSRR. 2013;2:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Demissie ZA, Erland LAE, Rheault MR, Mahmoud SS. The biosynthetic origin of irregular monoterpenes in lavandula isolation and biochemical characterization of a novel cis-prenyl diphosphate synthase gene, lavandulyl diphosphate synthase. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6333–6341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.431171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djilani A, Dicko A. The Therapeutic benefits of essential oils. In: Bouayed J, editor. Nutrition, Well-Being and Health. London: InTech Europe; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull Bot Soc Am. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ehtesham-Gharaee M, Hoseini BA, Khayyat MH, Emami SA, Asili J, Shakeri A, Hassani M, Ansari A, Arabzadeh S, Kasaian J, Behravan J. Essential oil diversity and molecular characterization of Ephedra species using RAPD analysis. Res J Pharmacogn. 2017;4:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili A, Amiri H, Rezazadeh S. The essential oils of Tanacetum pinnatum Boiss. a composite herbs growing wild in Iran. J Med Plants. 2009;3:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Franz C, Novak J. Sources of essential oils. In: Baser KHC, Buchbauer G, editors. Handbook of essential oils: science, Technology, and applications. New York: CRC Press; 2015. pp. 6–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi SG, Mahajan V, Bedi YS. Changing trends in biotechnology of secondary metabolism in medicinal and aromatic plants. Planta. 2015;241:303–317. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachino RRA, Sonmez C, Tonk GA, Bayram E, Yuce S, Telci I, Furan MA. RAPD and essential oil characterization of Turkish basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Plant Syst Evol. 2014;300:1779–1791. doi: 10.1007/s00606-014-1005-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert M (2011) Flora of China. http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=2&taxon_id=250097902

- Habibi Z, Biniyaz T, Ghodrati T, Masoudi S, Rustaiyan A. Constituents of Tanacetum paradoxum Bornm. and Tanacetum tabrisianum (Boiss.) Sosn. et Takht., from Iran. JEOR. 2007;19:11–13. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2007.9699216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick JL, Godt MJW. Effect of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:1291–1298. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks H, Elst DJD, van der, Putten FMS, Van, Bos R (2011) The Essential Oil of Dutch Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare L.). JEOR 2:155 – 62

- Hintze J (2007) NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah USA. http://www.ncss.com. Accessed 30 April 2014

- Hollingsworth PM. Refining the DNA Barcode for land plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:19451–19452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116812108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter WN. The non-mevalonate Pathway of Isoprenoid Precursor Biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21573–21577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N, Ougham H, Thomas H, Pasakinskiene I. Markers and mapping revisited: finding your gene. New Phytol. 2009;183:935–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo P, Sapru BL (1977) Flora of Ladakh. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehradun, pp 1–172

- Kamble RN, Mehta PP, Shinde VM. Aromatherapy as complementary and alternative medicine-systematic review. World J Pharm Res. 2014;3:144–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kazi MA, Reddy CRK, Jha B. Molecular phylogeny and barcoding of Caulerpa (Bryopsidales) based on the tufA, rbcL, 18S rDNA and ITS rDNA genes. PloS One. 2013;8:e82438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskitalo M, Lindén A, Valkonen JPT. Genetic and morphological diversity of Finnish tansy (Tanacetum vulgare L., Asteraceae) Theor Appl Genet. 1998;96:1141–1150. doi: 10.1007/s001220050850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keskitalo M, Pehu E, Simon J. Variation in volatile compounds from tansy (Tanacetum vulgare L.) related to genetic and morphological differences of genotypes. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2001;29:267–285. doi: 10.1016/S0305-1978(00)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiritikar KR, BB (1988) Indian Medicinal Plants. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehradun, pp 1–674

- Kitchlu S, Bakshi SK, Kaul MK, Bhan MK, Thapa RK, Agarwal SG. Tanacetum gracile Hook. f & T. A new source of lavandulol from Ladakh Himalaya (India) Flavour Fragr J. 2006;21:690–692. doi: 10.1002/ffj.1674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kocyan A, Qiu YL, Endress PK, Conti E. A phylogenetic analysis of Apostasioideae (Orchidaceae) based on ITS, trnL-F and matK sequences. Plant Syst Evol. 2004;247:203–213. doi: 10.1007/s00606-004-0133-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koli B, Gochar R, Meena SR, Chandra S, Bindu K. Domestication and nutrient management of Monarda citriodora Cer.ex Lag. in sub tropical region of Jammu (India) Int J Chem Studies. 2018;6:1259–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Kress WJ. Plant DNA Barcodes: Applications today and in the future. J Syst Evol. 2017;55:291–307. doi: 10.1111/jse.12254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lohani H, Chauhan N, Andola HC. Chemical composition of the essential oil of two Tanacetum species alpine region in Indian Himalaya. Natl Acad Sci Lett. 2012;35:95–97. doi: 10.1007/s40009-012-0032-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magiatis P, Skaltsounis AL, Chinou I, Haroutounian SA. Chemical composition and in-vitro antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of three Greek Achillea species. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. C. 2002;57:287–90. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-3-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan V, Rather IA, Awasthi P, Anand R, Gairola S, Meena SR, Gandhi SG. Development of chemical and EST-SSR markers for Ocimum genus. Ind Crops Prod. 2015;63:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.10.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan V, Sharma N, Kumar S, Bhardwaj V, Ali A, Khajuria RK, Gandhi SG. Production of rohitukine in leaves and seeds of Dysoxylum binectariferum: An alternate renewable resource. Pharm Biol. 2015;53:446–450. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.923006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathela CS, Padalia RC, Joshi RK. Variability in fragrance constituents of Himalayan Tanacetum species commercial potential. J Essent Oil Bear Pl. 2008;11:503–513. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2008.10643659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough DW, Bhupathy M, Piccolino E, Cohen T. Highly efficient terpenoid pheromone syntheses via regio- and stereocontrolled processing of allyllithiums generated by reductive lithiation of allyl phenyl thioethers. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:9727–9736. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)80712-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsenzadeh F, Chehregan A, Amiri H. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity of essential oils of Tanacetum parthenium in different developmental stages. Pharm Biol. 2011;49:920–926. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2011.556650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nano GM, Bicchi C, Frattini C, Gallino M. Wild Piedmontese plants. II. A rare chemotype of Tanacetum vulgare L., abundant in Piedmont (Italy) Planta Med. 1979;35:270–274. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1097215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Li WH. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1979;76:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polunin O, Stainton A. Flowers of the Himalaya. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1984. pp. 1–580. [Google Scholar]

- Ratha KK, Mishra SS, Arya JC, Joshi GC. Impact of climate change on diversity of Himalayan medicinal plant: A threat to ayurvedic system of medicine. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm. 2012;3:327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Roldán-Ruiz I, Dendauw J, Van Bockstaele E, Depicker A, Loose MDe. AFLP markers reveal high polymorphic rates in ryegrasses (Lolium spp.) Mol Breed. 2000;6:125–134. doi: 10.1023/A:1009680614564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozza AL, Pellizzon CH. Essential oils from medicinal and aromatic plants: A review of the gastroprotective and ulcer-healing activities. Fundam Clin Pha. 2013;27:51–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2012.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samant SS, Butola JS, Sharma A. Assessment of diversity, distribution, conservation status and preparation of management plan for medicinal plants in the catchment area of parbati hydroelectric project stage- III in Northwestern Himalaya. J Mt Sci. 2007;4:34–56. doi: 10.1007/s11629-007-0034-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sangwan NS, Farooqi AHA, Shabih F, Sangwan RS. Regulation of essential oil production in plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2001;34:3–21. doi: 10.1023/A:1013386921596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stappen I, Tabanca N, Ali A, Wedge DE, Wanner J, Kaul VK, Lal B, Jaitak V, Gochev VK, Schmidt E, Jirovetz L. Chemical composition and biological activity of essential oils from wild growing aromatic plant species of Skimmia laureola and Juniperus macropoda from Western Himalaya. Nat Prod Commun. 2015;10:1071–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappen I, Tabanca N, Ali A, Wedge DE, Wanner J, Kaul VK, Lal B, Jaitak V, Gochev VK, Schmidt E, Jirovetz L. Chemical composition and biological activity of essential oils of Dracocephalum heterophyllum and Hyssopus officinalis from Western Himalaya. Nat Prod Commun. 2015;10:33–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tétényi P, Kaposi P, Héthelyi E. Variations in the essential oils of Tanacetum vulgare. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:1539–1544. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(75)85347-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma M, Singh SK, Bhushan S, Pal HC, Kitchlu S, Koul MK, Saxena AK. Induction of mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis by an essential oil from Tanacetum gracile. Planta Med. 2008;74:515–520. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1074503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira RF, Grayer RJ, Paton A, Simon JE. Genetic diversity of Ocimum gratissimum L. based on volatile oil constituents, flavonoids and RAPD markers. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2001;29:287–304. doi: 10.1016/S0305-1978(00)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ. Secreting glandular trichomes: more than just hairs. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:675–679. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyerstahl P, Marschall H, Thefeld K, Rustaiyan A. Constituents of the essential oil of Tanacetum (syn.Chrysanthemum) fruticulosum Ledeb. from Iran. Flavour Fragr J. 1999;14:112–120. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(199903/04)14:2<112::AID-FFJ786>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi M, Nishioka M, Kondo T. Phenetic diversity in the Fritillaria camschatcensis population grown on the Sapporo campus of Hokkaido University. Landsc Ecol Eng. 2009;6:75–79. doi: 10.1007/s11355-009-0084-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.