Abstract

Introduction

Increasing the frequency of blood glucose monitoring aids the evaluation of glycemic variability and blood glucose control by antidiabetic drugs. It remains unclear, however, whether GLP-1 receptor agonists or basal insulin has a better effect on glycemic variability in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients who are inadequately controlled by metformin. We used a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS) to compare patients on a GLP-1 receptor agonist with patients on basal insulin in terms of glycemic variability.

Methods

This prospective randomized study assigned T2DM patients treated with metformin (N = 39) to either exenatide treatment or insulin glargine treatment for 16 weeks. Glycemic variability was assessed using a CGMS; hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), β-cell function, weight, body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference were also evaluated.

Results

Mean blood glucose level, continuous overlapping net glycemic action, mean amplitude of glycemic excursions, percentage of the time that the blood glucose value was > 10.0 mmol/L, and highest blood glucose level (P < 0.01–0.05) significantly decreased in both groups. Standard deviation of the mean glucose value, largest amplitude of glycemic excursions, and waist circumference significantly decreased for those treated with exenatide (P < 0.05), while no changes were observed with insulin glargine treatment. Percentage of the time that the blood glucose value was > 7.8 mmol/L decreased after insulin glargine use (P < 0.05) but not with the exenatide intervention. Similar decreases in fasting blood glucose and HbA1c and increases in the 1/homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, disposition index 30, and disposition index 120 were observed in both groups (P < 0.01–0.05). Reductions in weight and BMI were greater with exenatide than with insulin glargine treatment (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

In overweight and obese patients with T2DM inadequately controlled by metformin, exenatide and insulin glargine have similar efficacies in terms of glycemic variability, HbA1c alleviation, and β-cell function, but exenatide has a greater effect on body weight and BMI.

Keywords: Basal insulin, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, Glucose fluctuation, Type 2 diabetic mellitus

Introduction

For patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), increasing the frequency of blood glucose monitoring is beneficial for maintaining physiological blood glucose levels [1, 2]. Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) and hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c) are the most commonly used methods to assess short-term and long-term blood glucose control, respectively [3–5]. However, these measurements are inadequate for real-time blood glucose monitoring. A continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS) conveniently and accurately records real-time glycemic values and trends over multiple days by providing a large number of blood glucose recordings [2, 5–7]. A CGMS provides a detailed depiction of glycemic variability (GV) and efficiently analyzes rates of change in glucose levels [7, 8]. Wide fluctuations in blood glucose levels may lead to excessive glycosylation and oxidative stress and are associated with reduced endothelial function in patients with T2DM; these are key factors in the development of diabetic complications [9, 10]. Patients with glycemic lability often have long-standing diabetes with both beta-cell function and counter-regulatory hormone failure [11]. GV has recently been evaluated as a potential target for diabetic complication interventions, and the GV record provided by a CGMS may improve glycemic control [12–14].

Metformin, an oral antidiabetic drug, is the first-line treatment for T2DM. In patients with T2DM and poorly controlled blood glucose receiving metformin alone, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and basal insulin are used as optional antidiabetic drugs [15–17]. Studies involving patients with T2DM and poor glycemic control receiving metformin, a sulfonylurea, or a combination of metformin and a sulfonylurea found that the addition of exenatide minimized GV to a greater extent than the addition of insulin glargine, based on SMBG results [18, 19].

A previous study and meta-analysis found that liraglutide (1.8 and 1.2 mg), a long-term GLP-1 receptor agonist, provided greater reductions in HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose (FBG) than exenatide (10 μg b.i.d.), a short-term GLP-1 receptor agonist. Compared with insulin glargine, adding liraglutide or other long-term GLP-1 receptor agonists to metformin alone or with a sulfonylurea decreased body weight and led to significantly improved or at least noninferior glycemic control [20–22]. In contrast to Western countries, exenatide is a commonly and widely used short-term GLP-1 receptor agonist in China [23, 24]. It is unclear from the use of a CGMS, which is a reliable technology for monitoring glycemic control, whether exenatide or basal insulin has a better effect on GV for patients with T2DM and inadequate glycemic control who receive metformin. In the work described in the present paper, we used a CGMS to compare the effects of exenatide treatment with those of insulin glargine treatment on the GVs of overweight and obese T2DM patients with poor glycemic control using metformin.

Methods

Subjects

Thirty-nine T2DM patients with poor glycemic control after receiving metformin monotherapy were recruited from Drum Tower Hospital (affiliated with Nanjing University Medical School, China) and randomized to receive exenatide or insulin glargine treatment for 16 weeks. Random numbers were provided by third-party statisticians and block randomization was used. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a stable metformin dose ≥ 1.5 g/day over at least 8 weeks; (2) body mass index (BMI) ≥ 24 kg/m2; (3) HbA1c level between 7.0% and 10.0%; and (4) age between 18 and 70 years. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) renal dysfunction, defined as a serum creatinine level ≥ 1.5 mg/dL; (2) diseases causing acute or chronic hypoxia; (3) liver dysfunction, defined as an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level ≥ 3 times higher than the upper limit of normal; (4) history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) during the preceding year; (5) proliferative retinopathy; (6) positive pregnancy test result, breast-feeding, or refusal to use appropriate contraceptive methods; (7) systemic corticosteroid therapy during the preceding 2 months; (8) type 1 diabetes; and (9) use of other experimental drugs over the preceding 1 month. All patients included in the study provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Drum Tower Hospital, which is affiliated with Nanjing University Medical School (Protocol: AF/SQ-2014-072-01). The present study was monitored by the Drug Clinical Trial Agency Office of Drum Tower Hospital, which is affiliated with Nanjing University Medical School. Adverse events (AEs) were collected and recorded in case report form, and serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported in written form to the Institutional Review Board of the Drug Clinical Trial Agency Office and the Research Ethics Board of Drum Tower Hospital.

Endpoint

The primary endpoint of this study was the change in GV during a 16-week follow-up period. Secondary endpoints included changes in the following factors at 16 weeks: blood glucose, HbA1c, weight, BMI, waist circumference, insulin function, liver function, and lipid profile.

Protocol

This prospective, randomized, and parallel-design trial lasted 16 weeks. For the exenatide-treated patients, the initial dosage was 5 µg twice daily for 4 weeks, followed by a maintenance dose of 10 µg twice daily throughout the trial. For patients receiving insulin glargine, the initial dose was 8 IU once daily, followed by a titrated dosage of ≥ 2 IU every 3 days based on FBG levels during the first 4 weeks until the peripheral blood glucose levels reached 6.1 mmol/L; the insulin glargine dose was not adjusted over the final 12 weeks. GV was measured at baseline and during the last week. This study was registered with Clinical trials.gov (ID: NCT02325960).

Measurements

Glycemic Variability

GV was assessed at baseline and at the end of the study using a CGMS (Glod, Medtronic) for up to 72 h. The CGMS sensor was inserted into subcutaneous abdominal fat tissue, and the average electrical signal was recorded every 5 min, yielding 288 glucose level measurements per day and 864 data points for 3 consecutive days. According to the CGMS results, the following key parameters were calculated: (1) mean blood glucose (MBG) level, which was estimated as the average value and standard deviation (SD) of the 288 data points recorded during the 24 h of continuous glucose monitoring; (2) mean amplitude of glycemic excursion (MAGE), determined by calculating the arithmetic mean of the difference between consecutive peaks and nadirs if the difference was > 1 SD of mean glucose; (3) mean absolute value of daily differences, calculated as the mean absolute deviation of matched values measured during two consecutive 24-h periods of continuous glucose monitoring [25]; (4) the difference between the highest and lowest levels of blood glucose, calculated as the difference between the highest and lowest blood glucose values during 24 h of continuous glucose monitoring; (5) TBG > 7.8 mmol/L and TBG > 11.1 mmol/L, calculated as the percentage of the time that the blood glucose value (TBG) was > 7.8 and > 11.1 mmol/L, respectively, during 24 h; and (6) TBG < 3.9 mmol/L, calculated as the percentage of the time that the blood glucose value was < 3.9 mmol/L during 24 h [26].

Standard Meal Tolerance Test

All patients enrolled in our study underwent a standard meal tolerance test at baseline and after 16 weeks of intervention. Plasma glucose and insulin levels were measured 0, 30, 60, and 120 min after meal ingestion. The 1/homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (1/HOMA-IR) index and the Matsuda insulin sensitivity index (ISIM) were used to measure insulin sensitivity. The basal homeostasis model assessment of insulin secretion (HOMA-β), early-phase total insulin area under the curve divided by the total glucose area under the curve during the first 30 min of the standard meal tolerance test (InsAUC30/GluAUC30), and the total-phase total insulin area under the curve divided by the total glucose area under the curve during the 120 min of the oral glucose tolerance test (InsAUC120/GluAUC120) were used to calculate insulin release. The disposition index was used to express β-cell function [27–29]. Values were calculated using the following formulae: 1/HOMA-IR = 1/(Ins0 × Glu0/22.5); ISIM = 10,000/(Glu0 × Ins0 × average glucose 75-g oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT] × average insulin OGTT)1/2; HOMA-β = (20 × Ins0)/(Glu0 − 3.5); InsAUC30/luAUC30 = (Ins0 + Ins30)/(Glu0 + Glu30); InsAUC120/GluAUC120 = (Ins0 + 4 × Ins30 + 3 × Ins120)/(Glu0 + 4 × Glu30 + 3 × Glu120); DI30 = (InsAUC30/GluAUC30) × ISIM; and DI120 = (InsAUC120/GluAUC120) × ISIM [30].

Biochemical Analyses

Fasting serum HBA1c, ALT, AST, total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), triglyceride (TG), uric acid, and creatinine levels were measured at baseline and after 16 weeks of intervention.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with a significance level of α = 0.05. A previous study demonstrated that insulin glargine treatment results in a MAGE change from baseline at week 36 of − 0.3 ± 1.3 [31], while exenatide used twice daily results in an approximate MAGE change from baseline at week 16 of − 2.91 ± 3.15 [32]. Using SMBG data [33] from a head-to-head study between exenatide and glargine, we can conservatively estimate that the MAGE change from baseline in the exenatide group is approximate 2.55 ± 3.15, so the sample size per group needed to provide 80% power was calculated. Assuming a 10% subject drop-out rate, a total of 44 patients (22 per group) was targeted for randomization. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). The paired Student’s t test was used to analyze the pre- and post-intervention differences within each group. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test for differences between the intervention groups after adjusting for baseline. Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to determine the association between the variables and GV and HBA1c. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were done in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, as well as with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

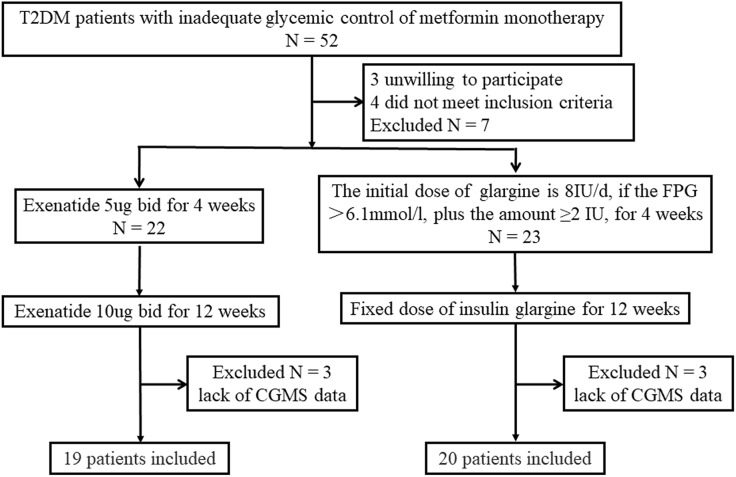

Out of the 52 patients treated with metformin monotherapy, 3 were not willing to participate in the trial and 4 did not meet the inclusion criteria. In total, 45 patients were randomized into the two treatment groups: 22 received exenatide therapy and 23 received insulin glargine therapy. Three patients in each group refused to undergo continuous glucose monitoring again after 16 weeks of intervention. Therefore, 39 patients completed the study (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients in the two treatment groups, including age and diabetes duration, were well matched (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study participants. Of the 52 participants recruited for the present study, 3 were unwilling to participate and 4 did not meet the inclusion criteria

Table 1.

Subject characteristics at baseline and after treatment

| Exenatide | Insulin glargine | Change in value | Estimated difference in value between groups Mean (95% CI) |

P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment Mean ± SE |

After treatment Mean ± SE |

P | Before treatment Mean ± SE |

After treatment Mean ± SE |

P | Exenatide Mean (95% CI) |

Insulin glargine Mean (95% CI) |

|||

| Number (n) | 19 | – | – | 20 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sex (male/female) | 12/7 | – | – | 10/10 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Age | 46.74 ± 2.31 | – | – | 49.45 ± 2.17 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Diabetic duration | 6.37 ± 0.99 | – | – | 4.35 ± 0.68 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Weight (kg) | 80.36 ± 2.35 | 76.85 ± 2.36 | < 0.001 | 74.75 ± 1.95 | 75.20 ± 1.98 | 0.263 | − 3.51 (− 5.09 to − 1.93) | 0.45 (− 0.37 to 1.27) | − 3.96 (− 5.65 to − 2.27) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.03 ± 0.50 | 26.81 ± 0.51 | < 0.001 | 27.08 ± 0.52 | 27.24 ± 0.55 | 0.258 | − 1.22 (− 1.78 to − 0.65) | 0.17 (− 0.13 to 0.47) | − 1.38 (− 1.99 to − 0.77) | < 0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 96.74 ± 1.50 | 93.71 ± 1.59 | 0.012 | 93.70 ± 1.52 | 93.30 ± 1.48 | 0.366 | − 3.03 (− 5.30 to − 0.75) | − 0.40 (− 1.30 to 0.50) | − 2.62 (− 5.03 to − 0.22) | 0.061 |

| ALT (U/L) | 31.79 ± 4.33 | 31.56 ± 3.96 | 0.949 | 36.46 ± 4.82 | 28.83 ± 3.81 | 0.027 | − 0.23 (− 7.75 to 7.28) | − 7.63 (− 14.27 to − 0.99) | 7.39 (− 2.27 to 17.05) | 0.183 |

| AST (U/L) | 22.28 ± 2.13 | 21.97 ± 2.18 | 0.855 | 24.78 ± 2.15 | 22.39 ± 1.92 | 0.103 | − 0.32 (− 3.92 to 3.29) | − 2.39 (− 5.31 to 0.53) | 2.07 (− 2.37 to 6.51) | 0.522 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.75 ± 0.17 | 1.61 ± 0.23 | 0.286 | 1.70 ± 0.17 | 1.49 ± 0.19 | 0.295 | − 0.15 (− 0.42 to 0.13) | − 0.21 (− 0.63 to 0.20) | 0.07 (− 0.42 to 0.55) | 0.744 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.55 ± 0.31 | 4.04 ± 0.28 | 0.019 | 4.45 ± 0.23 | 4.30 ± 0.15 | 0.557 | − 0.51 (− 0.93 to − 0.10) | − 0.14 (− 0.64 to 0.35) | − 0.37 (− 1.00 to 0.25) | 0.183 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 0.324 | 1.03 ± 0.05 | 1.11 ± 0.07 | 0.147 | − 0.04 (− 0.11 to 0.04) | 0.09 (− 0.03 to 0.21) | − 0.12 (− 0.26 to 0.01) | 0.083 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.42 ± 0.21 | 2.07 ± 0.20 | 0.010 | 2.36 ± 0.17 | 2.28 ± 0.11 | 0.617 | − 0.35 (− 0.60 to − 0.10) | − 0.09 (− 0.44 to 0.27) | − 0.26 (− 0.69 to 0.16) | 0.153 |

P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate significant differences between the groups

BMI body mass index, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, TG triglyceride, TC total cholesterol, LDL low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Biomedical Parameters

After intervention, body weight (Δ = − 3.51 kg, P < 0.001), BMI (Δ = − 1.22 kg/m2, P < 0.001), and waist circumference (Δ = − 3.03 cm, P = 0.012) significantly decreased in the exenatide treatment group but did not change in the insulin glargine group. Larger reductions in body weight (− 3.96 kg; 95% CI −5.65 to − 2.27 kg; P < 0.001) and BMI (− 1.38 kg/m2; 95% CI − 1.99 to − 0.77 kg/m2; P < 0.001) occurred in the exenatide group compared with the insulin glargine group. Although TC (P = 0.019) and LDL (P = 0.010) levels were significantly reduced after exenatide intervention, and ALT (P = 0.027) levels were significantly decreased after the insulin glargine treatment, there were no significant differences between the two groups (Table 1).

Glycemic Control and Insulin Function

After 16 weeks of intervention, HbA1c was significantly reduced by both exenatide treatment and by insulin glargine treatment (exenatide 8.01 ± 0.21 vs 6.83 ± 0.25%, Δ = − 1.18%, P < 0.001; insulin glargine 8.35 ± 0.24 vs 7.14 ± 0.16%, Δ = − 1.21%, P < 0.001; Table 2). Both exenatide and insulin glargine significantly reduced FBG (P = 0.002, P = 0.007, respectively); the blood glucose level measured at 30 min (P = 0.009) using a standard meal tolerance test was found to be significantly decreased with insulin glargine treatment (Table 2). The exenatide treatment group exhibited larger decreases in FBG (− 0.17 mmol/L; 95% CI − 1.64 to 1.30 mmol/L) and HbA1c (− 0.16%; 95% CI − 0.67% to 0.35%) than the insulin glargine group, although there were no statistical differences between the two groups (Table 2). Following both treatments, increases in 1/HOMA-IR (exenatide: from 0.35 ± 0.05 to 0.54 ± 0.08 μIU/mL, mmol/L, P = 0.035; insulin glargine: from 0.28 ± 0.03 to 0.47 ± 0.06 μIU/mL, mmol/L, P = 0.017), ISIM (exenatide: from 4.43 ± 0.71 to 7.13 ± 1.06 μIU/mL, mmol/L, P = 0.035), disposition index 30 (exenatide: from 41.94 ± 5.30 to 68.50 ± 11.06 mmol/L, mmol/L, P = 0.008; insulin glargine: from 36.40 ± 4.40 to 60.39 ± 6.24 mmol/L, mmol/L, P = 0.001), and disposition index 120 (exenatide: from 61.31 ± 9.64 to 97.12 ± 17.30 mmol/L, mmol/L, P = 0.020; insulin glargine: from 52.71 ± 6.87 to 88.33 ± 10.21 mmol/L, mmol/L, P = 0.006) were observed (Table 2); however, there were no statistical differences between the two groups.

Table 2.

Glucose control, insulin sensitivity, and β-cell function at baseline and after treatment

| Exenatide | Insulin glargine | Change in value | Estimated difference in value between groups Mean (95% CI) |

P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment Mean ± SE |

After treatment Mean ± SE |

P | Before treatment Mean ± SE |

After treatment Mean ± SE |

P | Exenatide Mean (95% CI) |

Insulin glargine Mean (95% CI) |

|||

| FBG (mmol/L) | 8.65 ± 0.53 | 6.88 ± 0.40 | 0.002 | 8.83 ± 0.48 | 7.23 ± 0.39 | 0.007 | − 1.77 (− 2.83 to − 0.72) | − 1.60 (− 2.70 to − 0.50) | − 0.17 (− 1.64 to 1.30) | 0.580 |

| 30 min glucose (mmol/L) | 11.03 ± 0.74 | 9.06 ± 0.87 | 0.061 | 11.90 ± 0.68 | 10.08 ± 0.59 | 0.009 | − 1.97 (− 4.05 to 0.10) | − 1.82 (− 3.13 to − 0.52) | − 0.15 (− 2.48 to 2.19) | 0.497 |

| 60 min glucose (mmol/L) | 14.27 ± 0.99 | 11.82 ± 1.03 | 0.080 | 14.70 ± 0.67 | 12.18 ± 0.66 | 0.091 | − 2.45 (− 5.23 to 0.33) | − 2.52 (− 3.92 to − 1.12) | 0.08 (− 2.82 to 2.97) | 0.844 |

| 120 min glucose (mmol/L) | 13.31 ± 0.88 | 11.71 ± 0.75 | 0.106 | 13.99 ± 0.90 | 12.77 ± 0.86 | 0.204 | − 1.59 (− 3.56 to 0.38) | − 1.22 (− 3.17 to 0.74) | − 0.37 (− 3.04 to 2.29) | 0.457 |

| Fasting insulin (uIU/mL) | 10.92 ± 1.85 | 10.03 ± 1.75 | 0.701 | 10.48 ± 1.02 | 9.62 ± 1.88 | 0.671 | − 0.89 (− 5.71 to 3.93) | − 0.86 (− 5.07 to 3.35) | − 0.03 (− 6.22 to 6.15) | 0.903 |

| 30 min insulin (uIU/mL) | 19.69 ± 3.03 | 17.57 ± 3.96 | 0.523 | 18.47 ± 2.12 | 22.48 ± 4.83 | 0.388 | − 2.12 (− 8.99 to 4.74) | 4.01 (− 5.57 to 13.59) | − 6.13 (− 17.37 to 5.10) | 0.298 |

| 60 min insulin (uIU/mL) | 30.26 ± 5.48 | 33.86 ± 8.82 | 0.646 | 29.92 ± 3.53 | 33.99 ± 6.26 | 0.525 | 3.60 (− 12.64 to 19.84) | 4.06 (− 9.19 to 17.32) | − 0.46 (− 20.78 to 19.85) | 0.970 |

| 120 min insulin (uIU/mL) | 35.65 ± 5.61 | 39.33 ± 8.87 | 0.549 | 38.38 ± 6.05 | 44.93 ± 8.61 | 0.436 | 3.67 (− 9.00 to 16.35) | 6.54 (− 10.81 to 23.90) | − 2.87 (− 23.36 to 17.62) | 0.756 |

| 1/HOMA-IR (μIU/mL, mmol/L) | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | 0.035 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.017 | 0.19 (0.02 to 0.37) | 0.19 (0.04 to 0.33) | 0.00 (− 0.22 to 0.22) | 0.718 |

| ISIM (μIU/mL, mmol/L) | 4.43 ± 0.71 | 7.13 ± 1.06 | 0.035 | 3.81 ± 0.54 | 5.29 ± 0.70 | 0.059 | 2.70 (0.22 to 5.19) | 1.48 (− 0.07 to 3.03) | 1.22 (− 1.62 to 4.06) | 0.218 |

| HOMA-B (IU/mol) | 55.55 ± 11.55 | 120.79 ± 48.44 | 0.153 | 54.17 ± 10.90 | 84.09 ± 30.50 | 0.361 | 65.24 (− 26.68 to 157.17) | 29.91 (− 37.74 to 97.57) | 35.33 (− 76.88 to 147.54) | 0.536 |

| InsAUC30/GluAUC30 (IU/mol) | 12.09 ± 1.90 | 15.29 ± 3.32 | 0.181 | 11.20 ± 1.64 | 14.77 ± 3.20 | 0.237 | 3.20 (− 1.65 to 8.05) | 3.58 (− 2.613 to 9.76) | − 0.37 (− 7.86 to 7.11) | 0.898 |

| InsAUC120/GluAUC120 (IU/mol) | 17.39 ± 3.17 | 22.03 ± 5.78 | 0.158 | 16.43 ± 2.73 | 21.94 ± 4.63 | 0.227 | 4.64 (− 2.02 to 11.29) | 5.51 (− 3.88 to 14.90) | − 0.87 (− 11.64 to 9.89) | 0.836 |

| DI 30 (mmol/L, mmol/L) | 41.94 ± 5.30 | 68.50 ± 11.06 | 0.008 | 36.40 ± 4.40 | 60.39 ± 6.24 | 0.001 | 26.57 (8.20 to 44.93) | 23.99 (12.71 to 35.27) | 2.57 (− 18.36 to 23.51) | 0.872 |

| DI 120 (mmol/L, mmol/L) | 61.31 ± 9.64 | 97.12 ± 17.30 | 0.020 | 52.71 ± 6.87 | 88.33 ± 10.21 | 0.006 | 35.81 (6.65 to 64.97) | 35.62 (12.24 to 59.00) | 0.19 (− 35.79 to 36.17) | 0.949 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.01 ± 0.21 | 6.83 ± 0.25 | < 0.001 | 8.35 ± 0.24 | 7.14 ± 0.16 | < 0.001 | − 1.21 (− 1.57 to − 0.85) | − 1.05 (− 1.41 to − 0.69) | − 0.16 (− 0.67 to 0.35) | 0.537 |

InsAUC30/GluAUC30 was calculated as the total insulin area under the curve divided by the total glucose area under the curve during the first 30 min of the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT); InsAUC120/GluAUC120 was calculated as the total insulin area under the curve divided by the total glucose area under the curve during the 120 min of the OGTT

P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate significant differences between the groups

FBG fasting blood glucose, 1/HOMA-IR 1/homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, ISIM Matsuda insulin sensitivity index, HOMA-β basal homeostasis model assessment of insulin secretion, DI30 disposition index 30, DI120 disposition index 120, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c

Continuous Glucose Monitoring

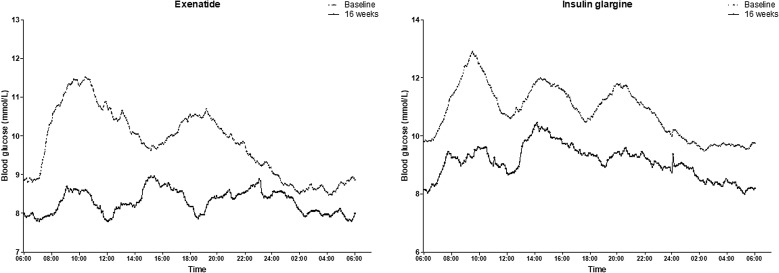

Overall, blood glucose fluctuations significantly improved after the exenatide and insulin glargine treatments (Fig. 2). There were similarly significant reductions in the MBG (exenatide Δ = − 1.25 ± 0.29 mmol/L, P < 0.001; insulin glargine Δ = − 1.83 ± 0.66 mmol/L, P = 0.007), continuous overlapping net glycemic action (CONGA) (exenatide Δ = − 1.13 ± 0.30 mmol/L, P < 0.001; insulin glargine Δ = − 2.09 ± 0.70 mmol/L, P = 0.015), and MAGE (exenatide Δ = − 1.20 ± 0.54 mmol/L, P = 0.001; insulin glargine Δ = − 1.47 ± 0.52 mmol/L, P = 0.001) values after the exenatide and insulin glargine interventions. There appeared to be smaller decreases in MBG (0.36 mmol/L; 95% CI − 1.00 to 1.72 mmol/L), CONGA (0.45 mmol/L; 95% CI − 0.94 to 1.84 mmol/L), and MAGE (0.20 mmol/L; 95% CI − 1.00 to 1.41 mmol/L) in the exenatide group when compared to the insulin glargine group, although there were no statistically significant differences. After exenatide intervention, there were significant reductions in the standard deviation of the mean glucose (Δ = 0.70 ± 0.24 mmol/L, P = 0.001) and largest amplitude of glycemic excursions (Δ = − 2.32 ± 1.06 mmol/L, P = 0.004), while no changes were observed after the insulin glargine intervention (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Mean interstitial glucose values at baseline and after treatment with exenatide (a) and insulin glargine (b)

Table 3.

Glycemic variability at baseline and after treatment

| Exenatide | Insulin glargine | Change in value | Estimated difference in value between groups Mean (95% CI) |

P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment Mean ± SE |

After treatment Mean ± SE |

P | Before treatment Mean ± SE |

After treatment Mean ± SE |

P | Exenatide Mean (95% CI) |

Insulin glargine Mean (95% CI) |

|||

| MBG (mmol/L) | 9.77 ± 0.40 | 8.32 ± 0.44 | < 0.001 | 10.85 ± 0.54 | 9.04 ± 0.54 | 0.007 | − 1.45 (− 2.06 to − 0.85) | − 1.82 (− 3.01 to − 0.57) | 0.36 (− 1.00 to 1.72) | 0.824 |

| SDBG (mmol/L) | 1.87 ± 0.15 | 1.19 ± 0.13 | 0.001 | 2.02 ± 0.14 | 1.71 ± 0.16 | 0.187 | − 0.68 (− 1.06 to − 0.31) | − 0.31 (− 0.79 to 0.17) | − 0.37 (− 0.96 to 0.21) | 0.022 |

| MODD (mmol/L) | 1.75 ± 0.21 | 1.52 ± 0.17 | 0.215 | 2.01 ± 0.18 | 1.82 ± 0.13 | 0.248 | − 0.24 (− 0.63 to 0.16) | − 0.19 (− 0.53 to 0.15) | − 0.05 (− 0.53 to 0.44) | 0.294 |

| MAGE (mmol/L) | 4.51 ± 0.32 | 2.94 ± 0.33 | 0.001 | 5.62 ± 0.46 | 3.84 ± 0.39 | 0.001 | − 1.57 (− 2.42 to − 0.73) | − 1.78 (− 2.70 to − 0.86) | 0.20 (− 1.00 to 1.41) | 0.322 |

| LAGE (mmol/L) | 7.82 ± 0.59 | 5.18 ± 0.53 | 0.004 | 8.60 ± 0.63 | 6.97 ± 0.87 | 0.166 | − 2.64 (− 4.29 to − 0.99) | − 1.63 (− 4.01 to 0.75) | − 1.00 (− 3.77 to 1.77) | 0.083 |

| CONGA (mmol/L) | 8.82 ± 0.39 | 7.53 ± 0.40 | < 0.001 | 9.55 ± 0.49 | 7.80 ± 0.47 | 0.015 | − 1.30 (− 1.91 to − 0.68) | − 1.75 (− 3.12 to − 0.38) | 0.45 (− 0.94 to 1.84) | 0.973 |

P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences between the groups

MBG mean blood glucose level, SDBG standard deviation of the mean glucose value, MODD absolute mean of daily differences, MAGE mean amplitude of glycemic excursions, LAGE largest amplitude of glycemic excursions, CONGA continuous overlapping net glycemic action

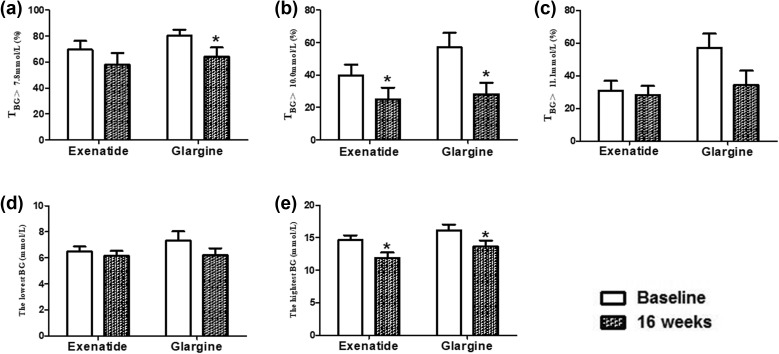

Both interventions significantly decreased the percentage of the time that TBG > 10.0 mmol/L [exenatide Δ = − 14.79 ± 4.97%, P = 0.008; insulin glargine Δ = − 25.11 ± 10.16%, P = 0.024 (Fig. 3b)] and the highest blood glucose level [exenatide Δ = − 2.70 ± 0.72 mmol/L, P = 0.001; insulin glargine Δ = − 2.49 ± 1.16 mmol/L, P = 0.045 (Fig. 3e)]. The percentage of the time that TBG was > 7.8 mmol/L was significantly decreased in the insulin glargine treatment group (P = 0.030) but not in the exenatide group (Fig. 3a). However, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Fig. 3.

Effects of exenatide treatment and glargine treatment on the percentage of the time that the blood glucose value (TBG) was > 7.8 mmol/L (a), > 10.0 mmol/L (b), or > 11.1 mmol/L (c) as well as the lowest (d) and the highest (e) blood glucose (BG) values. *P < 0.05, 16 weeks vs baseline

Correlative Analysis

For all subjects, there were significant positive correlations between ΔHbA1c and the reductions in MBG, CONGA, and Max BG (0 < r < 1; P < 0.05; Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations between glycemic variability and glycated hemoglobin

| ∆HBA1c | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | P | |

| ∆MBG (mmol/L) | 0.498 | 0.001 |

| ∆CONGA (mmol/L) | 0.512 | 0.002 |

| ∆Max BG (mmol/L) | 0.439 | 0.006 |

P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance

MBG mean blood glucose level, CONGA continuous overlapping net glycemic action, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c

Discussion

This study compared the effects of treatment with the short-term GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide and insulin glargine treatment on GV in overweight and obese patients with T2DM and poor glycemic control who were receiving metformin monotherapy. Importantly, our results using a CGMS revealed that similar improvements in GV, HBA1c, and β-cell function were achieved with exenatide treatment and insulin glargine treatment, although greater body weight and BMI reductions were achieved with the exenatide treatment during the 16-week intervention. After treatment, waist circumference was significantly decreased in the exenatide group, but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Recent studies have suggested that glycemic fluctuation is a useful indicator of the effectiveness of blood glucose control and the prevention of diabetes complications [1, 2, 10]. Less frequent monitoring of blood glucose levels using SMBG may lead to inaccurate GV assessment and could falsely suggest a lack of or a decrease in glycemic fluctuation [3, 5, 6]. A CGMS automatically records blood glucose levels every 5 min, achieving up to 288 measurements per day, which provide a better measure of the extent of glycemic fluctuation and overall trends [7, 8]. Therefore, we used a CGMS in this study to monitor blood glucose.

Glycemic fluctuation following the use of a GLP-1 receptor agonist was compared with the GV observed after the introduction of basal insulin. Results showed that although the exenatide and glargine treatments were both associated with similar significant improvements in HbA1c from baseline, exenatide treatment resulted in greater improvements in GV than insulin glargine treatment for previously uncontrolled glucose levels when combined with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy. Improvements in GV were also observed in patients with suboptimally controlled diabetes using metformin or a sulfonylurea [18, 19]. However, the average daily risk range as well as the low and high blood glucose indices, indicative of the fluctuation in blood glucose levels, were based on SMBG and not on the more accurate CGMS [18, 19]. We found that FBG and HbA1c were significantly reduced after exenatide and insulin glargine intervention. Compared with baseline levels, glycemic fluctuation results calculated by the CGMS indicated that both exenatide treatment and insulin glargine treatment significantly decreased MBG, CONGA, MAGE, and the highest blood glucose value, as well as the percentage of time that the blood glucose was > 10.0 mmol/L through the day. Following the standard meal tolerance test, insulin glargine significantly decreased blood glucose levels at 30 min; glucose levels at 60 and 120 min showed a downward trend after exenatide intervention and insulin glargine intervention. The decrease in MAGE with insulin glargine treatment might due to improved β-cell function and insulin resistance associated with improved glycemic control.

Other long-term GLP-1 receptor agonists that only require once-daily or once a week injection have become widely used or are beginning to find wider use in China. The long-term GLP-1 receptor agonists liraglutide and semaglutide have shown beneficial effects on CVD and mortality-related CVD in T2DM patients, although there would appear to be no difference in the effects of once-weekly exenatide, the other long-term GLP-1 receptor agonist, or lixisenatide, a short-term GLP-1 receptor agonist [34–36]. HbA1c and FBG showed greater reductions with liraglutide treatment rather than exenatide treatment [23, 24], and significantly greater improvements in HbA1c were seen with liraglutide and semaglutide than with insulin glargine [20–22]. Whether the beneficial effects of liraglutide and semaglutide for CVD were the result of greater decreases in GV requires further study.

Regarding insulin resistance and β-cell function, the 1/HOMA-IR, disposition index 30, and disposition index 120 improved with either exenatide treatment or insulin glargine treatment. Only the ISIM improved to a greater extent with exenatide treatment than with insulin glargine treatment. These results indicate that β-cell function and insulin resistance improved following a 16-week course of exenatide or insulin glargine treatment.

Overweight and obese patients in the cooperative meta-analysis group of the China Obesity Task Force were enrolled in our study [25]. The results showed that exenatide treatment resulted in weight loss while insulin glargine treatment did not. Standardized weight is an important part of integrated T2DM management because weight loss is associated with improvements in β-cell function and insulin action, it makes long-term glycemic control management easier, and it may favorably affect other comorbid diseases such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperuricemia [15]. An increasing waist circumference contributes to central obesity and is an independent risk factor for T2DM, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and CVD [26, 37]. In the present study, waist circumference only decreased in the exenatide-treated group.

An important finding from our study was a positive association between GV and HbA1c level, which may indicate that exenatide and insulin glargine facilitate glycemic control and reduce GV, thus aiding diabetes management.

The main AEs reported in the exenatide-treated group were gastrointestinal intolerance/appetite suppression (17 subjects), nausea (which relieved over time; 3 subjects), and abdominal distension (4 subjects). No patients in the group treated with insulin glargine suffered gastrointestinal intolerance, hypoglycemia, or other AEs. No hypoglycemia events occurred in these patients, which may be because prandial insulin and drugs stimulating insulin secretion were not used. No participants withdrew from the study due to these AEs, and no SAEs occurred in the present study.

There are a number of limitations of our study. Only 39 patients were enrolled, and this small sample size may have had a negative impact on the statistical analysis. It might affect the comparison of waist circumference between the two intervention groups, for greater reduction of waist circumference in exenatide group might be confirmed after enlarging the sample size. The results of the present study could be further confirmed by expanding the sample size, using a blinded design, testing long-term GLP-1 receptor analogists, and potentially developing a multicenter research study. In addition, the study period was 16 weeks, which may not have been sufficient to assess additional benefits relating to the GV. Since a fixed dosage of exenatide was given in the exenatide group after 4 weeks and the dosage of the insulin glargine was only titrated during the first four weeks, rising FBG levels in some insulin-glargine-treated patients during the following 12 weeks may have affected glucose control in the insulin glargine group.

Conclusions

Our study showed that comparable improvements in GV, HBA1c, and β-cell function can be achieved in overweight and obese T2DM patients with inadequate glycemic control who were receiving metformin monotherapy by combining that treatment with either exenatide or insulin glargine. Compared to insulin glargine, exenatide had a superior impact on body weight and BMI. Waist circumference was significantly reduced with exenatide treatment, but there was no statistically significant difference from the insulin glargine treatment.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Investigator Initiated-Sponsored Clinical Research from AstraZeneca Investment (China) Co., Ltd. (ISSEXEN0034), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570736, 81570737), Medical and Health Research Projects of Nanjing Health Bureau in Jiangsu Province of China (YKK14055), Project of Standardized Diagnosis and Treatment of Key Diseases in Jiangsu Province of China (2015604), China Diabetes Young Scientific Talent Research Project (2017-N-05), and Nanjing University Central University Basic Scientific Research (14380296). Drum Tower Hospital (affiliated with Nanjing University Medical School, China) provided sponsorship for article processing charges. Our study sponsor did not fund the journal’s article processing charges. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Editorial Assistance

Editage, a brand of Cactus Communications, offered professional English language editing.

Authorship

All the named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Ting-Ting Yin, Yan Bi, Ping Li, Shan-Mei Shen, Xiao-Lu Xiong, Li-Jun Gao, Can Jiang, Yan Wang, Wen-Huan Feng, and Da-Long Zhu have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed for the current analysis are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.5982262.

Contributor Information

Wen-Huan Feng, Email: fengwh501@163.com.

Da-Long Zhu, Email: zhudalong@nju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Siegelaar SE, Holleman F, Hoekstra JB, DeVries JH. Glucose variability; does it matter? Endocr Rev. 2010;31(2):171–182. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin YP, Su XF, Yin GP, et al. Blood glucose fluctuations in hemodialysis patients with end stage diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complicat. 2015;29(3):395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee MK, Lee KH, Yoo SH, Park CY. Impact of initial active engagement in self-monitoring with a telemonitoring device on glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3866. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03842-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tildesley HD, Mazanderani AB, Ross SA. Effect of Internet therapeutic intervention on A1C levels in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(8):1738–1740. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clar C, Barnard K, Cummins E, Royle P, Waugh N, Aberdeen Health Technology Assessment Group. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(12):1–140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Malanda UL, Bot SD, Nijpels G. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in noninsulin-using type 2 diabetic patients: it is time to face the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1):176–178. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy JC, Davies MJ, Holman RR, Group TS. Continuous glucose monitoring detected hypoglycaemia in the Treating to Target in Type 2 Diabetes Trial (4-T) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;131:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei Q, Sun Z, Yang Y, Yu H, Ding H, Wang S. Effect of a CGMS and SMBG on maternal and neonatal outcomes in gestational diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19920. doi: 10.1038/srep19920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54(6):1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Flaviani A, Picconi F, Di Stefano P, et al. Impact of glycemic and blood pressure variability on surrogate measures of cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1605–1609. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murata GH, Duckworth WC, Shah JH, Wendel CS, Hoffman RM. Sources of glucose variability in insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Outcomes in Veterans Study (DOVES) Clin Endocrinol. 2004;60(4):451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueira FR, Umpierre D, Casali KR, et al. Aerobic and combined exercise sessions reduce glucose variability in type 2 diabetes: crossover randomized trial. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen O, Korner A, Chlup R, et al. Improved glycemic control through continuous glucose sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy: prospective results from a community and academic practice patient registry. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(4):804–811. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson K, Zapletalova J, Kudlova P, et al. Benefits of three-month continuous glucose monitoring for persons with diabetes using insulin pumps and sensors. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czechoslovakia. 2009;153(1):47–51. doi: 10.5507/bp.2009.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm—2017 Executive Summary. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(2):207–238. doi: 10.4158/EP161682.CS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eng C, Kramer CK, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014;384(9961):2228–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61335-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buse JB, Bergenstal RM, Glass LC, et al. Use of twice-daily exenatide in basal insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):103–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Barnett AH, Burger J, Johns D, et al. Tolerability and efficacy of exenatide and titrated insulin glargine in adult patients with type 2 diabetes previously uncontrolled with metformin or a sulfonylurea: a multinational, randomized, open-label, two-period, crossover noninferiority trial. Clin Ther. 2007;29(11):2333–2348. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCall AL, Cox DJ, Brodows R, Crean J, Johns D, Kovatchev B. Reduced daily risk of glycemic variability: comparison of exenatide with insulin glargine. Diabetes Technol Therap. 2009;11(6):339–344. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus once-daily insulin glargine as add-on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):355–366. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met + SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52(10):2046–2055. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1472-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Stranks S, et al. Once weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-3): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2234–2243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60406-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twigg SM, Daja MM, O’Leary BA, Adena MA. Once-daily liraglutide (1.2 mg) compared with twice-daily exenatide (10 mug) in the treatment of type 2 diabetes patients: an indirect treatment comparison meta-analysis. J Diabetes. 2016;8(6):866–876. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier JJ, Rosenstock J, Hincelin-Mery A, et al. Contrasting effects of lixisenatide and liraglutide on postprandial glycemic control, gastric emptying, and safety parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes on optimized insulin glargine with or without metformin: a randomized, open-label trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(7):1263–1273. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou BF, Cooperative Meta-Analysis Group of the Working Group on Obesity in China. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults—study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2002;15(1):83–96. [PubMed]

- 26.Murphy KG. Editorial overview: endocrine and metabolic diseases: waistline weapons: new therapeutic avenues for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;25:iv–vi. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li C, Yang H, Tong G, et al. Correlations between A1c, fasting glucose, 2 h postload glucose, and beta-cell function in the Chinese population. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51(4):601–608. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0563-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(9):1462–1470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stancakova A, Javorsky M, Kuulasmaa T, Haffner SM, Kuusisto J, Laakso M. Changes in insulin sensitivity and insulin release in relation to glycemia and glucose tolerance in 6,414 Finnish men. Diabetes. 2009;58(5):1212–1221. doi: 10.2337/db08-1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pistrosch F, Kohler C, Schaper F, Landgraf W, Forst T, Hanefeld M. Effects of insulin glargine versus metformin on glycemic variability, microvascular and beta-cell function in early type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50(4):587–595. doi: 10.1007/s00592-012-0451-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irace C, Fiorentino R, Carallo C, Scavelli F, Gnasso A. Exenatide improves glycemic variability assessed by continuous glucose monitoring in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Therap. 2011;13(12):1261–1263. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heine RJ, Van Gaal LF, Johns D, et al. Exenatide versus insulin glargine in patients with suboptimally controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(8):559–569. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-8-200510180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1228–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2247–2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui R, Qi Z, Zhou L, Li Z, Li Q, Zhang J. Evaluation of serum lipid profile, body mass index, and waistline in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:445–452. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S104803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed for the current analysis are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.