Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular mortality is a major concern for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Insulin therapy significantly contributes to a high rate of death in these patients. We have performed a meta-analysis comparing cardiac and non-cardiac-related mortality following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in a sample of patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus (ITDM).

Methods

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if: (1) they were trials or cohort studies involving patients with T2DM post-PCI; (2) the outcomes in ITDM were separately reported; and (3) they reported cardiac death and non-cardiac death among their clinical endpoints. ITDM patients with any degree of coronary artery disease were included. The analysis was carried out using RevMan version 5.3 software, and data were reported with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) as the main parameters.

Results

A total of 4072 participants with ITDM were included, of whom 1658 participants and 2414 participants were extracted from randomized controlled trials and observational cohorts, respectively. Analysis of all data showed that death due to cardiac causes was significantly higher in patients with ITDM (OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.79–2.59; P = 0.00001). At 1 year of follow-up, cardiac death was still significantly higher compared to non-cardiac death (OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.47–3.88; P = 0.0004), and this result did not change with a longer follow-up period (3–5 years) (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.70–2.56; P = 0.00001). Death due to cardiac causes was still significantly higher in the subpopulations of patients with everolimus-eluting stents (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.26–4.26; P = 0.007), paclitaxel-eluting stents (OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.63–3.39; P = 0.00001), sirolimus-eluting stents (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.67–2.67; P = 0.00001), and zotarolimus-eluting stents (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.11–4.05; P = 0.02), respectively.

Conclusions

Mortality due to cardiac causes was significantly higher than that due to non-cardiac causes in patients with ITDM who had undergone PCI. The same conclusion could be drawn from analyses focused on different follow-up periods, types of coronary stents, and type of study data used.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Cardiac mortality, Insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus, Non-cardiac mortality, Percutaneous coronary intervention

Introduction

In this era of modern medicine, nearly three hundred and fifty million cases of diabetes have been diagnosed to date worldwide [1]. Mortality is a great concern among this patient population, especially in those with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in co-existence with cardiovascular disease (CVD). Values calculated by the World Health Organization show that there are approximately three million deaths annually due to T2DM and its related complications [2]. Cardiovascular mortality, which was evaluated in the Second Cardiovascular Outcome Trial Summit of the Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease (D&CVD) EASD Study Group [3], is also a major health risk factor in the population of patients with T2DM.

T2DM is an independent cause of mortality. Although data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service–National Sample Cohort showed that 78% of diabetes-related deaths could not be ascribed to diabetes [4], other studies have shown that in T2DM patients with CVD who were re-vascularized by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), insulin therapy significantly contributed to a high death rate [5].

We have therefore conducted a meta-analysis to compare cardiac- versus non-cardiac-related mortality following PCI in a sample of patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus (ITDM). To date, few studies have systematically assessed cardiac versus non-cardiac mortality in such patients following PCI.

Methods

Searched Databases and Key Words/Index Terms

We systematically and thoroughly searched the MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, and Google Scholar databases. the following key words/index terms were used to identify articles of possible interest:

T2DM + PCI, or

T2DM + coronary angioplasty, or

T2DM + PCI, or

ITDM + PCI, or

Cardiac death + ITDM + PCI.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included in the meta-analysis review if: (1) they were trials or cohort studies based on patients with T2DM following PCI; (2) they separately reported outcomes in patients with ITDM; (3) they reported cardiac death and non-cardiac death among their endpoints.

Studies were excluded from the systematic review if: (1) they did not involve patients with T2DM following PCI; (2) they did not separately report patients with ITDM; (3) they did not report cardiac death among their clinical outcomes; (4) they were repeated studies or duplicate studies.

Participants

All participants in the studies ultimately included in our systematic review were patients with ITDM. However, the extent of the coronary artery disease varied among studies and included ITDM patients with stable coronary artery disease, de novo coronary artery disease, acute myocardial infarction, single-vessel coronary artery disease, multi-vessel coronary artery disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease participating in the studies included in the systematic review

| First author/year/reference of studies included in the meta-analysis | Coronary artery disease status of study participants | Diabetes status of study participants |

|---|---|---|

| Antoniucci 2004 [9] | Acute myocardial infarction | ITDM |

| Bangalore 2016 [10] | Stable coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Banning 2010 [11] | Left main and/or three-vessel coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Dangas 2014 [12] | Multiple-vessel coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Jain 2010 [13] | Single- or multi-vessel coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Kappetein 2013 [14] | Complex coronary artery disease: de novo three-vessel and/or left main coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Kirtane 2008 [15] | Single de novo lesion in a native coronary artery | ITDM |

| Kirtane 2009 [16] | Stable coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Mehran 2004 [17] | Multi-vessel coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Nakamura 2010 [18] | Coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Simek 2013 [19] | All corner patients with coronary artery disease | ITDM |

| Tada 2011 [20] | Coronary artery disease | ITDM |

ITDM insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus

Definition of Endpoints

In this analysis, cardiac death was compared with non-cardiac death in diabetic patients who received insulin treatment. Therefore, the main focus was on: (1) cardiac mortality: death due to cardiac causes; (2) non-cardiac mortality: death which was not related to cardiac causes.

Data Extraction and Review

The following data were extracted by three reviewers independently of each other: (1) patients with ITDM; (2) the number of events corresponding to cardiac death; (3) the number of events corresponding to non-cardiac death; (4) baseline features; (5) methodological features of each study; (5) type of study.

The methodological qualities for the randomized controlled trials were assessed by using the guidelines set down in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [6]. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [7] was used to assess the methodological qualities for the observational studies.

Statistical Analysis

The computer program RevMan version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used as analytical software. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Heterogeneity was assessed by two meta-analytical methods: (1) The Cochrane Q statistic test (a P value of ≤ 0.05 indicates a statistically significant result); (2) the I2 statistic test (the lower the value, the lower the heterogeneity).

A fixed (I2 < 50%) effects model or a random (I2 > 50%) model was used based on the value of I2 that was obtained.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This meta-analysis is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Searched Outcomes

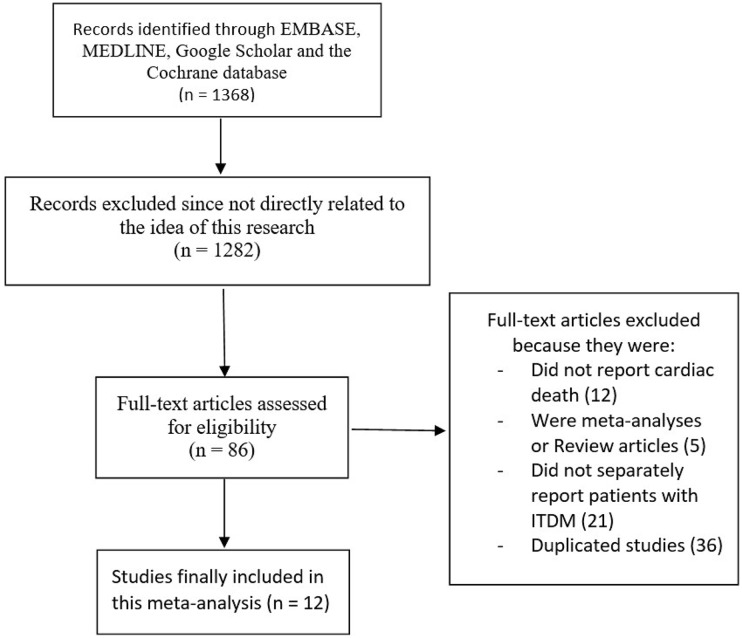

We followed the PRISMA guideline for this analysis [8].

A total of 1368 publications were identified from the database search using the chosen key words/index terms. Publications were excluded and eliminated based on the following criteria:

They were not related to the aim of this meta-analysis (n = 1282).

They did not report cardiovascular death, but instead reported total death among their clinical outcomes (n = 12).

They were meta-analyses or review articles themselves (n = 5).

They did not separately report patients with ITDM (n = 21).

They were duplicates of the same study (n = 36).

Ultimately, a total number of 12 articles (6 randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and 6 observational cohorts) [9–20] were included in this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection. ITDM Insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus

General and Baseline Features of the Participants

A total number of 4072 patients with ITDM who participated in 12 observational studies/RCTs were included in this meta-analysis. Of these, 1658 participants were extracted from RCTs and 2414 participants were extracted from observational studies. Two studies had a follow-up period of < 1 year, four studies had a follow-up period of 1 year, and six studies had a follow-up period of > 1 [range 3–5] year). One study reported patients who were treated with a bare metal stent, whereas all of the other studies involved patients who were treated with drug-eluting stents DES, specifically everolimus-eluting stents (EES), paclitaxel-eluting stents (PES), sirolimus-eluting stents (SES), and zotarolimus-eluting stents (ZES), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Total number of events and other features of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| First author/year/reference of studies included in the meta-analysis | Type of study | Number of patients with cardiac death | Number of patients with non-cardiac death | Total number of patients | Duration of follow-up period | Type of stent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antoniucci 2004 [9] | Observational | 16 | 6 | 84 | 6 months | – |

| Bangalore 2016 [10] | RCT | 18 | 8 | 747 | 1 year | PES, EES |

| Banning 2010 [11] | RCT | 9 | 2 | 88 | 1 year | PES |

| Dangas 2014 [12] | RCT | 42 | 20 | 325 | 5 years | DES (SES and PES) |

| Jain 2010 [13] | Observational | 29 | 14 | 644 | 1 year | ZES |

| Kappetein 2013 [14] | RCT | 16 | 5 | 89 | 5 years | PES |

| Kirtane 2008 [15] | RCT | 15 | 13 | 265 | 4 years | PES, BMS |

| Kirtane 2009 [16] | RCT | 0 | 0 | 144 | 1 year | ZES, PES |

| Mehran 2004 [17] | Observational | 1 | 1 | 81 | In-hospital | – |

| Nakamura 2010 [18] | Observational | 13 | 10 | 200 | 3 years | SES |

| Simek 2013 [19] | Observational | 63 | 25 | 489 | 3 years | EES, SES, PES |

| Tada 2011 [20] | Observational | 149 | 80 | 996 | 3 years | SES |

RCT randomized controlled trials, BMS bare metal stent, SES sirolimus eluting stents, DES drug eluting stents, ZES zotarolimus eluting stents, EES everolimus eluting stents, PES paclitaxel eluting stents

The baseline features of the participants with ITDM are given in Table 3. Based on the features which are listed, there was no significant difference between those patients who died due to a cardiac cause and those who died due to a non-cardiac cause.

Table 3.

Baseline features of the participants

| First author/year/reference of studies included in the meta-analysis | Age (years) | Males (%) | Hypertension (%) | Dyslipidemia (%) | Current smoker (%) | Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | NCD | CD | NCD | CD | NCD | CD | NCD | CD | NCD | CD | NCD | |

| Antoniucci 2004 [9] | 69.0 | 69.0 | 65.0 | 65.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | – | − |

| Bangalore 2016 [10] | 58.5 | 58.5 | 71.0 | 71.0 | 65.6 | 65.6 | 76.2/ | 76.2 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 26.1 | 26.1 |

| Banning 2010 [11] | 65.4 | 65.4 | 71.0 | 71.0 | 69.9 | 69.9 | 81.5 | 81.5 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 29.5 | 29.5 |

| Dangas 2014 [12] | 62.6 | 62.6 | 61.3 | 61.3 | 87.5 | 87.5 | – | − | 17.9 | 17.9 | 30.5 | 30.5 |

| Jain 2010 [13] | 66.6 | 66.6 | 62.2 | 62.2 | 82.1 | 82.1 | 67.9 | 67.9 | 13.9 | 13.9 | – | − |

| Kappetein 2013 [14] | 65.4 | 65.4 | 71.0 | 71.0 | 70.0 | 70.0 | 82.0 | 82.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 29.5 | 29.5 |

| Kirtane 2008 [15] | 63.0 | 63.0 | 64.7 | 64.7 | 82.1 | 82.1 | 74.0 | 74.0 | 18.4 | 18.4 | – | − |

| Kirtane 2009 [16] | 63.3 | 63.3 | 71.0 | 71.0 | 76.7 | 76.7 | 81.4 | 81.4 | 64.8 | 64.8 | – | − |

| Mehran 2004 [17] | 63.0 | 63.0 | 52.0 | 52.0 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 71.0 | 71.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | – | − |

| Nakamura 2010 [18] | 66.2 | 66.2 | 66.2 | 66.2 | 68.1 | 68.1 | 58.0 | 58.0 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 24.0 | 24.0 |

| Simek 2013 [19] | 65.1 | 65.1 | 69.2 | 69.2 | 70.6 | 70.6 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 32.1 | 32.1 | 28.8 | 28.8 |

| Tada 2011 [20] | 66.7 | 66.7 | 67.0 | 67.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 | – | − | 16.0 | 16.0 | 24.1 | 24.1 |

CD Cardiac death, NCD non-cardiac death

The methodological qualities of the studies were also assessed. RCTs were assessed with the recommended features of the Cochrane collaboration guidelines [6]. Grades were given to define the limit of bias (low, low to moderate, moderate, and high). For the observational studies, NOS scores [7] were given, with a maximum number of nine points (a higher score indicates better quality study), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Assessment of bias risk

| First author/year/reference of studies included in the meta-analysis | Bias risk grade/score | Bias status |

|---|---|---|

| RCTs (Cochrane assessment) | ||

| Kirtane 2009 [16] | B | Low to moderate |

| Bangalore 2016 [10] | A | Low |

| Banning 2010 [11] | A | Low |

| Dangas 2014 [12] | A | Low |

| Kirtane 2008 [15] | B | Low to moderate |

| Kappetein 2013 [14] | B | Low to moderate |

| Observational studies (NOS assessment) | ||

| Antoniucci 2004 [9] | 6 | Moderate |

| Jain 2010 [13] | 8 | Low |

| Mehran 2004 [17] | 6 | Moderate |

| Nakamura 2010 [18] | 6 | Moderate |

| Simek 2013 [19] | 7 | Low |

| Tada 2011 [20] | 6 | Moderate |

NOS Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

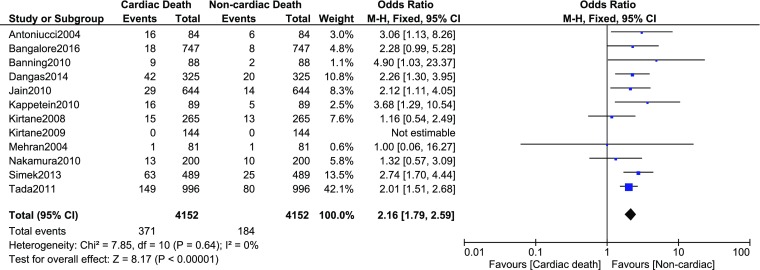

Death Due to Cardiac Versus Non-cardiac Causes Following PCI in Patients with ITDM

Analysis of the combined data extracted from the included RCTs and observational studies revealed that death due to cardiac causes was significantly higher in patients with ITDM than death due to non-cardiac causes(OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.79–2.59; P = 0.00001; I2 = 0%) when (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cardiac versus non-cardiac death following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with ITDM. CI Confidence interval, M–H Mantel–Haenszel test

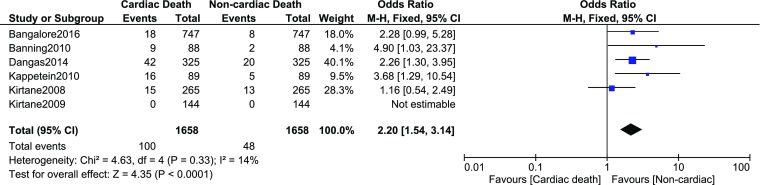

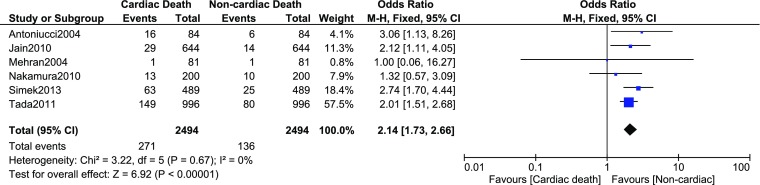

However, data from RCTs and observational studies were also analyzed separately. When we considered only data obtained from RCTs in the analysis, death from cardiac causes was still significantly higher in patients with ITDM (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.54–3.14; P = 0.0001; I2 = 14%) (Fig. 3). Similarly, when we considered only data obtained from observational cohorts, death due to cardiac causes was significantly higher in the ITDM patients (OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.73–2.66; P = 0.00001; I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Cardiac versus non-cardiac death following PCI in patients with ITDM based only on data obtained from randomized controlled trials

Fig. 4.

Cardiac versus non-cardiac death following PCI in ITDM based only on data obtained from observational cohorts

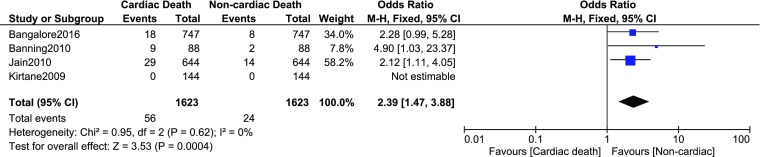

When all the studies with a follow-up period of 1 year were analyzed together, cardiac death was still significantly higher in patients with ITDM compared to non-cardiac death (OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.47–3.88; P = 0.0004; I2 = 0%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Cardiac versus non-cardiac death following PCI in ITDM during a follow-up period of 1 year

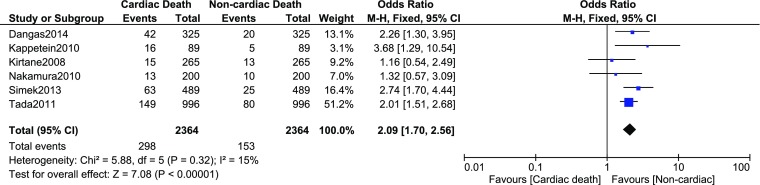

When studies with longer follow-up periods were considered (range 3–5 years), mortality due to cardiac causes was still significantly higher in these patients with ITDM (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.70–2.56; P = 0.00001; I2 = 15%) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Cardiac versus non-cardiac death following PCI in ITDM during a longer follow-up period (range 3–5 years)

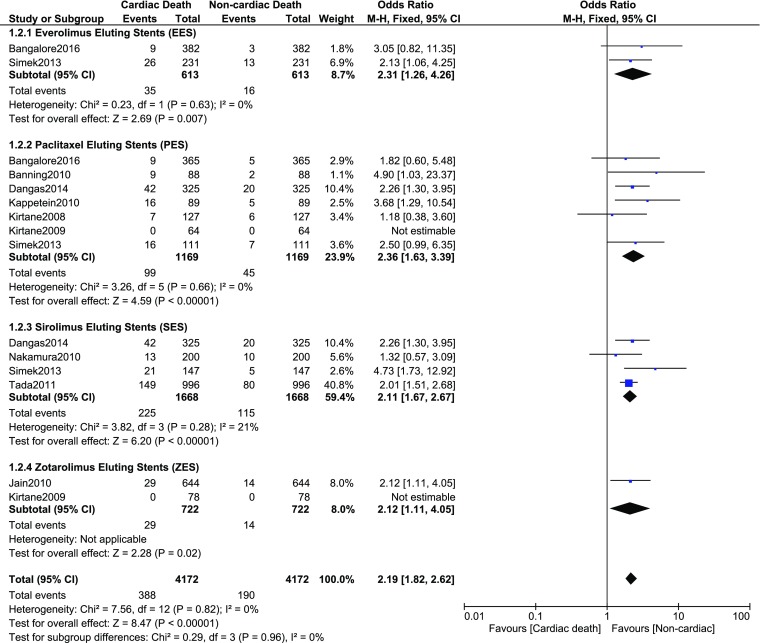

When the participants were analyzed based on the type of stents, death due to cardiac causes was still significantly higher in those patients having an EES (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.26–4.26; P = 0.007, I2 = 0%) compared to those a PES (OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.63–3.39; P = 0.00001; I2 = 0%), SES (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.67–2.67; P = 0.00001; I2 = 21%), or ZES (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.11–4.05; P = 0.02), as shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Cardiac versus non-cardiac death following PCI in ITDM according to drug-eluting stents

Discussion

Cardiovascular death is a major concern among patients with T2DM who are treated by PCI. The results of our meta-analysis show that cardiovascular death in patients with ITDM who have undergone PCI was significantly higher that death due to non-cardiac causes. This result remained consistent even when data from the RCTs and observational studies were analyzed separately.

To assess the effect of differences in follow-up periods on the cause of death in this patient group, we also separately analyzed the data from all of the studies included in the meta-analysis which reported a follow-up period of 1 year. As reported in the "Results" section, cardiac death was still significantly higher in this subpopulation of patients with ITDM. When a longer follow-up period (3–5 years) was considered, the major cause of death remained cardiovascular.

We also assessed the impact of coronary stents on the results by analyzed the data from all studies based on the types of coronary stents which were implanted (EES, PES, SES, and ZES). However, cardiovascular cause of death was still significantly higher in the patients with ITDM.

An 11-year retrospective analysis of death certificates in Shanghai also showed an increasing occurrence of CVD among Chinese patients who had previously developed diabetes mellitus [21], with 29.9% of deaths among those diabetic patients due to cardiovascular causes; in comparison, other causes represented only small percentages. However, causes of death based specifically on patients with ITDM were not analyzed in that study.

Finally, even though research has shown diabetes mellitus to be independently associated with death due to CVD, other studies have shown that insulin therapy also makes a major contribution to such an outcome [5, 22]. In addition, female gender and higher co-morbidities have also been suggested to further contribute to such outcomes [23]. These factors should further be investigated in future studies.

There are a few limitations to our analysis. First, the total number of patients was relatively small, especially for the analysis on impact of types of coronary stents on cause of death in patients with ITDM treated by PCI. Second, data from different categories of participants (those with stable coronary artery disease, multi-vessel coronary artery disease, single-vessel coronary artery disease, left main coronary artery disease, and acute myocardial infarction) were combined and analyzed. Third, the anti-platelet agents which were used post-PCI were not taken into consideration and this might also have had an impact on the mortality rate.

Conclusions

In patients with ITDM, mortality due to cardiac causes was significantly higher than that due to non-cardiac causes following PCI. The same conclusion was reached when different lengths of follow-up periods were assessed, when different data sets were used (total data set, data from the observational cohort or RCTs separately), and when types of coronary stents which were implanted were assessed.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Qiang Wang, Hao Liu, and Jiawang Ding were responsible for the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the initial manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Qiang Wang wrote the manuscript and is the first author.

Disclosures

The authors Qiang Wang, Hao Liu and Jiawang Ding have nothing to disclose. They do not have any personal, financial, commercial, or academic conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This meta-analysis is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.6247415.

References

- 1.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnell O, Standl E, Catrinoiu D, et al. Report from the 2nd Cardiovascular Outcome Trial (CVOT) Summit of the Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease (D&CVD) EASD Study Group. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0508-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang YM, Kim YJ, Park JY, Lee WJ, Jung CH. Mortality and causes of death in a national sample of type 2 diabetic patients in Korea from 2002 to 2013. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bundhun PK, Li N, Chen MH. Adverse cardiovascular outcomes between insulin-treated and non-insulin treated diabetic patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:135. doi: 10.1186/s12933-015-0300-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley; 2008. p. 187–241.

- 7.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2009. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. Accessed 19 Oct 2009.

- 8.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcareinterventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoniucci D, Valenti R, et al. Impact of insulin requiring diabetes mellitus on effectiveness of reperfusion and outcome of patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(9):1170–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bangalore S, Bhagwat A, Pinto B, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with insulin-treated and non-insulin-treated diabetes mellitus: secondary analysis of the TUXEDO trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(3):266–273. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banning AP, Westaby S, Morice MC, et al. Diabetic and nondiabetic patients with left main and/or 3-vessel coronary artery disease: comparison of outcomes with cardiac surgery and paclitaxel-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(11):1067–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dangas GD, Farkouh ME, Sleeper LA, et al. Long-term outcome of PCI versus CABG in insulin and non-insulin-treated diabetic patients: results from the FREEDOM trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(12):1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain AK, Lotan C, Meredith IT, et al. Twelve-month outcomes in patients with diabetes implanted with a zotarolimus-eluting stent: results from the E-Five Registry. Heart. 2010;96(11):848–853. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.184150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Morice MC, et al . Treatment of complex coronary artery disease in patients with diabetes: 5-year results comparingoutcomes of bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention in the SYNTAX trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43(5):1006–1013. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirtane AJ, Ellis SG, Dawkins KD, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents in patients with diabetes mellitus: pooled analysis from 5 randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(7):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirtane AJ, Patel R, O’Shaughnessy C, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcomes in diabetics from the ENDEAVOR IV trial: randomized comparison of zotarolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents in patients with coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(10):967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehran R, Dangas GD, Kobayashi Y, et al. Short- and long-term results after multivessel stenting in diabetic patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(8):1348–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura M, Yokoi H, Hamazaki Y, et al. Impact of insulin-treated diabetes and hemodialysis on longterm clinical outcomes following sirolimus-elutingstent deployment. Insights from a sub-study of the Cypher Stent Japan Post-Marketing Surveillance (Cypher J-PMS) Registry. Circ J. 2010;74(12):2592–2597. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simsek C, Räber L, Magro M, et al. Long-term outcome of the unrestricted use of everolimus-eluting stents compared to sirolimus-eluting stents and paclitaxel-eluting stents in diabetic patients: the Bern–Rotterdam diabetes cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;170(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tada T, Kimura T, Morimoto T, et al. Comparison of three year clinical outcomes after sirolimus eluting stent implantation among insulin-treateddiabetic, non-insulin-treated diabetic, and non-diabetic patients from J-Cypher registry. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(8):1155–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu M, Li J, Li Z, et al. Mortality rates and the causes of death related to diabetes mellitus in Shanghai Songjiang District: an 11-year retrospective analysis of death certificates. BMC Endocr Disord. 2015;15:45. doi: 10.1186/s12902-015-0042-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bundhun PK, Wu ZJ, Chen MH. Coronary artery bypass surgery compared with percutaneous coronary interventions in patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;6(15):2. doi: 10.1186/s12933-015-0323-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bundhun PK, Pursun M, Huang F. Are women with type 2 diabetes mellitus more susceptible to cardiovascular complications following coronary angioplasty?: a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0645-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.