Abstract

A significant part of the proteome is composed of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). These proteins do not fold into a well-defined structure and behave like ordinary polymers. In this work, we consider IDPs that have the tendency to aggregate, model them as heteropolymers that contain a small number of associating monomers, and use computer simulations to compare the aggregation of such IDPs that are grafted to a surface or free in solution. We then discuss how such grafting may affect the analysis of in vitro experiments and could also be used to suppress harmful aggregation.

Introduction

Proteins are usually thought of as having a well-defined tertiary structure (unique native state) that is determined by their amino acid sequence. In the simplest models of protein folding (1), proteins fold into this spatial structure based on the sequence of hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids. Because hydrophobic monomers attract and hydrophilic monomers repel each other, the former are found in the interior and the latter are found on the surface of folded proteins (2). This guarantees the solubility and suppresses the aggregation of proteins in the aqueous environment of the cell. The above strategy fails in the case of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) that do not fold into a well-defined three-dimensional structure, but still have a functional role to play in the cell (3, 4, 5). One such example is the nucleoporins (nups) of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (6, 7, 8). The NPC controls the transport of macromolecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. The nups are block copolymers comprised of a folded domain that forms the rigid scaffold of the NPC, and an unfolded domain that is enriched in hydrophobic phenylalanine-glycine repeats (FG nups). A coarse representation of the NPC corresponds to FG nups grafted to the inner surface of a channel (9). FG nups have alternating hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains along their backbone, which raises the probability of association among them when they are in an aqueous environment. Although there is agreement on the importance of associations between FG nups and transport receptors (10, 11), it is unclear how big of a role attractive interactions between nups plays in the NPC (12), with one school of thought asserting that the nups form a strong hydrogel and another stating that they are mainly brush-like (13). Another example of such a system are neurofilaments, which are important for maintaining axon structure in neurons (14, 15). They also contain flexible sidearms, which respond dynamically to the environment (16) and associate via electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged residues (17). Although attractive interactions between the disordered subdomains play an important role in stabilizing the structure of the neurofilament network, aggregation of neurofilaments is also associated with neurodegenerative diseases (18).

Note that in both the NPC and the neurofilaments, the IDPs are grafted to a surface. Although grafting can provide clear benefits for localization and introduce a degree of spatial ordering in the system, a less explored aspect is how aggregation of IDPs is affected by the grafting. In cases where the IDPs need to associate to perform their function, grafting may affect the partitioning of bound monomers between intra- and intermolecular bonds and suppress the formation of harmful larger aggregates. Furthermore, the fact that the chains (in the NPC and in neurofilaments) are grafted in vivo, but experiments that test the behavior of IDPs are often done on free chains in solution in vitro, could potentially mean that although the in vitro experiments can give us some level of understanding, the propensity to aggregate may be different in the two systems and lead one to erroneous conclusions about in vivo behavior. For instance, experiments on nups in solution suggest that they form hydrogels (19, 20). How this is affected by grafting has not yet been explored. Taking such ideas as our inspiration, in this article we examine the differences between model systems of disordered polymers when they are either free or grafted. In particular, we shall investigate how the aggregation of soluble heteropolymers with a small number of attractive groups is affected by the grafting constraint.

Materials and Methods

The model system we choose is a system of M polymer chains each of monomers (beads). Most of the beads on this chain interact via the repulsive part of a Lennard-Jones potential, and the backbone of the chain is connected via the FENE potential (see Supporting Material). We designate some of the beads along the backbone of this polymer as being “stickers” (in the terminology of (21)) that have an attractive Lennard-Jones interaction of strength with other such stickers. We then study how the system behaves when the chains are either grafted to a surface or are free to move throughout the volume (the latter case has been previously studied using both mean-field (22) and simulation methods (23)). In this work, we use Langevin dynamics to simulate the above model of associating polymers. Simulation details are available in the Supporting Material.

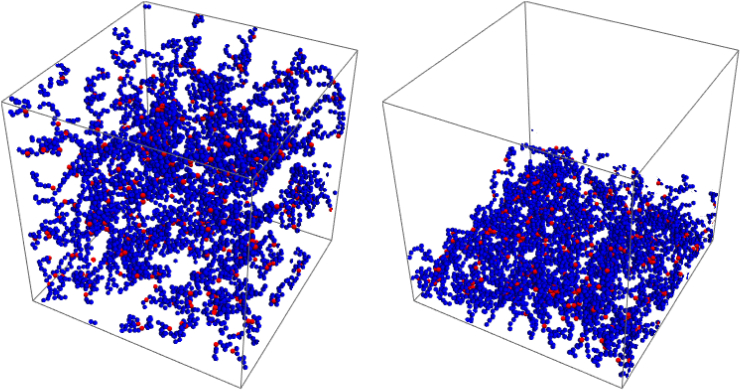

In Fig. 1 we show a snapshot of the system for grafted and free chains. There are various parameters we can control in this system: the density ρ of free chains, the grafting density of grafted chains, the strength of interaction between stickers , the number of stickers on a chain, and their positions along the chain contour. We fix the interaction parameter at , and restrict our focus to the cases where the number of stickers is either three or four (<10% of the beads) The number of stickers reasonably aligns with FG repeat concentration in nups (13). This choice also guarantees that 1) individual polymers remain soluble and assume expanded conformations in dilute solution (24), and 2) that even though associations are quite strong, they remain reversible in the sense that bonds form and break in the course of the simulation. The main quantity we are interested in studying is how the system behaves as a function of the density. There is a problem here, as the two systems have different control parameters defining their density. In the system of free chains, we control the overall density by setting the volume of the simulation. In the system of grafted chains, we control the grafting density, but the monomer density can vary because it depends on the state of extension of the chains. This, in turn, depends on the repulsion between chains, the persistence length, the strength and number of stickers, etc. To compare the free and the grafted chains, we define the following control parameter L, which characterizes the separation between the chains:

| (1) |

| (2) |

This parameter L therefore gives us a length scale for comparison, corresponding to the mean distance between the centers of mass of neighboring chains. See Supporting Material to see how L depends on the monomer density for both the free and grafted systems.

Figure 1.

Snapshots of the free and the grafted system. The blue beads represent the normal, hard sphere only interaction beads. The red beads are the stickers. The free chains can translate along the system whereas the grafted chains are grafted in a square lattice pattern to the bottom of the system. To see this figure in color, go online.

Results

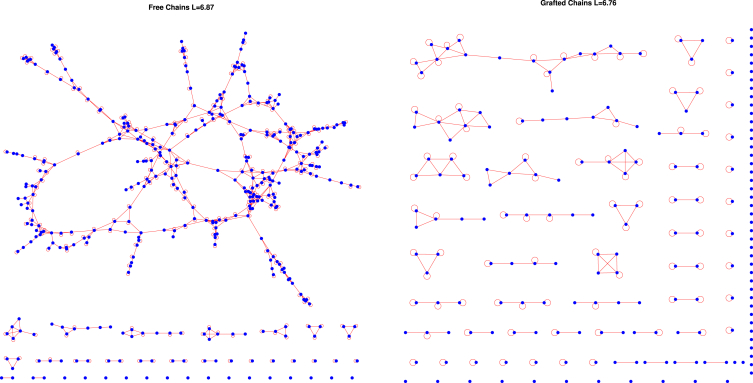

We first look at how the association of the polymers changes as a function of the parameter L for the free and the grafted chains. To do this, we need a suitable definition of what it means when we say that two polymers are bound together. We choose to define two polymers as being bound together when any of their attractive groups are within a cutoff distance of 1.5 (in units of the bead diameter σ, see Supporting Material) from each other. As there are multiple attractive groups per polymer, larger structures can form from these pairwise interactions, i.e. when polymer A is bound to polymer B, which is bound to polymer C, there is a polymer cluster of size 3. We can categorize all these pairwise interactions on a graph of the polymers, where an edge between any two polymers indicates that the two are bound. An example of this can be seen in Fig. 2 for both free and grafted chains. Chains can be either bound to other chains, to themselves (represented as loops), or not bound to anything at all. Every snapshot of the system will have some configuration of this sort.

Figure 2.

An example of graphs of the free and grafted systems. Every blue node represents one of the polymers. A red edge between the polymers means that the two polymers are bound by at least one pair of stickers. A loop means that the polymer is bound to itself. Both of these cases are for four stickers per chain and . To see this figure in color, go online.

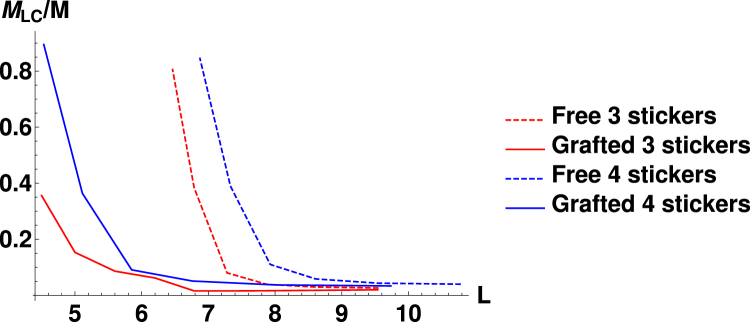

Using these graphs, we can analyze the properties of the systems of free and grafted chains. A pertinent issue when discussing gelation is the percolation of bound polymer chains in the system. In other words, what proportion of the total number of chains are found in the largest cluster of the system (where is the number of polymers in the largest cluster)? If this number is one then that means that all the chains in the system are bound in the same cluster (a gel), whereas if it is zero then none of the chains are bound. We can study this ratio for both the grafted and the free systems as a function of L. We look at this for cases of both three and four attractive monomers per chain.

As seen in Fig. 3, there is a large difference in when gelation occurs for grafted and free systems as a function of L. As expected, when there are four attractive beads the polymers associate into one big cluster at larger values of L than when there are three beads. However, the most interesting aspect is when the transitions occur for the grafted and the free chains. When the chains are free, the value of L required for the transition to one large interconnected cluster is significantly higher than for the grafted chains. Note that under conditions when the free chains form a connected cluster that percolates through the system, only small localized clusters are observed for grafted chains (Fig. 2). This concurs with the observation of “bundles” in simulations of grafted FG nups (25).

Figure 3.

The size of the largest cluster as a proportion of the total number of polymers in each system for chains with three and four attractive points. To see this figure in color, go online.

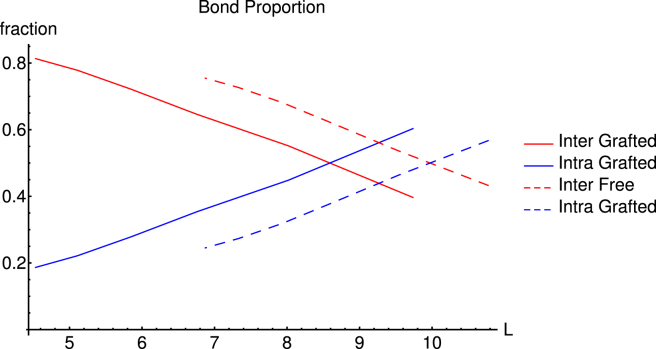

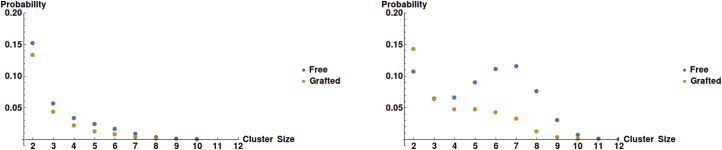

The metric, , does not provide complete information about the complexity of the system because the two largest clusters in the free and the grafted system may be of the same size, but could have significantly different distributions of edges or vertex arrangements. For example, consider the question whether the bonds in the system are intrachain (two attractive beads on the same chain bound together) or interchain (two attractive beads bound that belong to two different polymers). In Fig. 4 we observe that both the free and the grafted polymers follow a similar pattern for the proportion of bonds that are intrachain or interchain. As expected, the fraction of intrachain bonds decreases and that of interchain bonds increases with increasing concentration. The main difference is a shift in the value of L where the crossover from intrachain to interchain association occurs. Because in our model, the attractive interactions between stickers are nonsaturating (there is no imposed limit on the size of clusters of stickers), it is interesting to compare the numbers of stickers in clusters of grafted and free chains. In Fig. 5 we show the number of stickers per cluster for the two systems for (below gel point concentration for both free and grafted chains) and for (above gel point concentration for free but not for grafted chains). Below the percolation threshold, both distributions fall monotonically with cluster size as the formation of large clusters of stickers is suppressed by excluded volume repulsions between the chains attached to the stickers in the clusters; however, a maximum in the distribution of cluster sizes (at ∼7 stickers per cluster) is observed above the gel point for the free chains. This correlates strongly with the lifetimes of each cluster, as seen in Fig. S1, which also exhibits a maximum at eight to nine stickers per cluster. The existence of this maximum reflects the interplay of the attraction between stickers (that favors larger clusters) and excluded volume repulsions and loss of conformational entropy (both increasing with cluster size).

Figure 4.

The fraction of the total number of bonds that are either inter- or intrabonds for polymers with four stickers, for both the grafted and free cases. Both have a transition from mainly intrabonds to mainly interbonds, but this transition occurs at larger L for the free chains. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 5.

The probability that a sticker is found in a cluster that contains a given number of stickers. Distributions are shown for both free and grafted systems at L = 6.75 (right) and L = 9.5 (left). Beyond the gel transition of the free system, there is a maximum for at intermediate cluster sizes (for the same value of L a shoulder is observed in the grafted case). To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

In this work we used computer simulations to study the simplest model of free and grafted IDPs—that of a heteropolymer consisting mostly of repulsive and some attractive monomers. To model water-soluble IDPs, the parameters were chosen such that 1) the radii of gyration of isolated polymers are only weakly perturbed by the presence of associating monomers, and 2) the stretching of individual grafted chains is similar to that of a polymer brush in good solvent (see Supporting Material). Note that for the value of the interaction parameter and the range of concentrations in our study, if the stickers were not parts of otherwise repulsive polymers, they would be far into the solid regime. The fact that the stickers are short segments of otherwise repulsive polymers suppresses aggregation and limits the maximum possible size of clusters to ∼12–14 stickers. This is due to several factors. First, the hard sphere repulsion of the monomers attached to the stickers reduces the second virial coefficient between the polymers (21) and makes it more difficult for the stickers to bind together. Second, the clustering of the stickers comes at some entropic cost (it limits the conformational space of the polymers).

Although it is not immediately clear whether grafting would have a significant effect on aggregation, our results suggest that the formation of large aggregates is strongly suppressed by grafting the IDPs to a surface. Note, however, that comparison between two different systems depends on the conditions at which they are studied, and ideally, these conditions should be the same. Unfortunately, there is an inherent ambiguity as to whether the free and the grafted systems should be compared at the same distance between monomers or at the same distance between chains. For free polymers, both distances can be controlled by adjusting the volume of the system, but for grafted polymers only the distance between the chains L can be controlled by adjusting the grafting density (because chains in the brush can stretch, the distance between monomers is not fixed by the grafting constraint). A large difference between the aggregation propensities of free and grafted chains is found when the comparison is made at fixed L, but only minor differences are observed if the comparison is made at similar monomer concentrations, where for the grafted systems the monomer concentration is measured as an average over the thickness of the brush. We would like to emphasize that this ambiguity is not a handicap of our model, as it would be present in any experiment that attempts to compare systems of free and grafted polymers. We do not anticipate that changing the geometry of the grafting, i.e., grafting onto the interior of a cylindrical surface or onto two surfaces, would affect the gelation point as long as the monomer densities were the same.

There are intriguing insights from this model that may be of relevance to biological systems. For instance, in the NPC there is some confusion over whether the nups form either a gel or a brush in vivo (12). Experimental studies on free nups can possibly provide some answers on which of these two outcomes is more likely. However, given the differences observed in the results section, such experiments need to take into account that the gel point may be different if the chains were grafted, depending on the various parameters involved in the problem. There are obviously differences between our model and the real system, which has a curved geometry and many different types of polymers, persistence lengths, interactions, etc. However, it may help to understand some of the observed irregularities in this field.

A related question is why are any IDPs in many living systems attached to surfaces? Obviously, if there is a need to localize chains somewhere, grafting will ensure this. However, there is another possibility: that grafting of chains may be a mechanism by which biological systems can control the extent and the strength of aggregation. In such unfolded proteins, both hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains are exposed to the aqueous environment, leading to the possibility of aggregation. Large aggregates, either from natively unfolded or misfolded proteins, can be biologically harmful. By keeping these proteins grafted to a surface, one can maintain some functionally important degree of association as well as suppress the formation of aggregates.

Author Contributions

D.O. and Y.R. designed the research and wrote the article. D.O. performed the research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation and the Israeli Centers for Research Excellence program of the Planning and Budgeting Committee.

Editor: Monika Fuxreiter.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods and four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30063-8.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Pande V.S., Grosberg A.Y., Tanaka T. Heteropolymer freezing and design: towards physical models of protein folding. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2000;72:259–314. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson C.M. Principles of protein folding, misfolding and aggregation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;15:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunker A.K., Silman I., Sussman J.L. Function and structure of inherently disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Lee R., Buljan M., Babu M.M. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:6589–6631. doi: 10.1021/cr400525m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandhu K.S. Intrinsic disorder explains diverse nuclear roles of chromatin remodeling proteins. J. Mol. Recognit. 2009;22:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jmr.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck M., Hurt E. The nuclear pore complex: understanding its function through structural insight. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:73–89. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denning D.P., Patel S.S., Rexach M. Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: the FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2450–2455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437902100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen N.P., Huang L., Rexach M. Proteomic analysis of nucleoporin interacting proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:29268–29274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tagliazucchi M., Peleg O., Szleifer I. Effect of charge, hydrophobicity, and sequence of nucleoporins on the translocation of model particles through the nuclear pore complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:3363–3368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isgro T.A., Schulten K. Binding dynamics of isolated nucleoporin repeat regions to importin-beta. Structure. 2005;13:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma J., Goryaynov A., Yang W. Super-resolution 3D tomography of interactions and competition in the nuclear pore complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:239–247. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osmanović D., Fassati A., Hoogenboom B.W. Physical modelling of the nuclear pore complex. Soft Matter. 2013;9:10442–10451. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peleg O., Lim R.Y. Converging on the function of intrinsically disordered nucleoporins in the nuclear pore complex. Biol. Chem. 2010;391:719–730. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan A., Rao M.V., Nixon R.A. Neurofilaments at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:3257–3263. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deek J., Chung P.J., Safinya C.R. Neurofilament sidearms modulate parallel and crossed-filament orientations inducing nematic to isotropic and re-entrant birefringent hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2224. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayanthi L., Stevenson W., Gebremichael Y. Conformational properties of interacting neurofilaments: Monte Carlo simulations of cylindrically grafted apposing neurofilament brushes. J. Biol. Phys. 2013;39:343–362. doi: 10.1007/s10867-012-9293-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck R., Deek J., Safinya C.R. Structures and interactions in ‘bottlebrush’ neurofilaments: the role of charged disordered proteins in forming hydrogel networks. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012;40:1027–1031. doi: 10.1042/BST20120101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Chalabi A., Miller C.C.J. Neurofilaments and neurological disease. BioEssays. 2003;25:346–355. doi: 10.1002/bies.10251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labokha A.A., Gradmann S., Görlich D. Systematic analysis of barrier-forming FG hydrogels from Xenopus nuclear pore complexes. EMBO J. 2013;32:204–218. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milles S., Huy Bui K., Lemke E.A. Facilitated aggregation of FG nucleoporins under molecular crowding conditions. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:178–183. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cates M.E., Witten T.A. Chain conformation and solubility of associating polymers. Macromolecules. 1986;19:732–739. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semenov A.N., Rubinstein M. Thermoreversible gelation in solutions of associative polymers. 1. statics. Macromolecules. 1998;31:1373–1385. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalatur P.G., Khokhlov A.R., Semenov A.N. Aggregation processes in self-associating polymer systems: computer simulation study of micelles in the superstrong segregation regime. Macromol. Theory Simul. 1996;5:713–747. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada J., Phillips J.L., Rexach M.F. A bimodal distribution of two distinct categories of intrinsically disordered structures with separate functions in FG nucleoporins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2010;9:2205–2224. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000035-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao L., Schulten K. Transport-related structures and processes of the nuclear pore complex studied through molecular dynamics. Structure. 2009;17:449–459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.